Episode 10: People of the Land

This is The Siècle, Episode 10: People of the Land.1

After months spent focusing on the affairs of kings, armies and politicians, it’s time to focus on the lives of ordinary French people in the early 19th Century. But I’ll warn you in advance: this is not going to be a cheery episode. That’s because this introduction to poorer French men and women is beginning with arguably the poorest of them all: the millions of French peasants.

The first question, and possibly the trickiest, is what exactly is a “peasant”? There’s no one definition.

Etymologically, “peasant” derives from the French word paysan, which means someone from the pays, or countryside — or, more poetically, “people of the land.”2

In general, we can think of peasants as preindustrial subsistence farmers. That is, they are farmers who rely on their crops to eat, and haven’t seen their lives transformed by the industrial revolution. There’s also an element of social class to it, too — we tend not to speak of subsistence farmers in 19th Century America, for example, as being “peasants,” because the social structures that helped define peasantry in Europe just didn’t exist in the United States.

But to that general definition we have to add complications. As one scholar noted, “Rural France is almost infinitely diverse, and almost any generalization about the peasantry becomes partially false as soon as it is formulated.”3

For example, I spoke of peasants as being subsistence farmers. Does that mean that those farmers who grew grapes instead of wheat on their tiny plots of land were not peasants because they transformed their crop into wine for the market? More significantly, as we’ll soon find out, few “peasants” were purely farmers, engaging in crafts, trade and even industry as well as working the land. I’ll tend to err on the side of an expansive definition of the peasantry, but this is not an uncontroversial position.

Still, if it’s hard to define peasants rigorously, everyone in Restoration France knew that peasants existed, and that there were a lot of them. How many, of course, is difficult to discern. By one metric, more than 80 percent of France’s population of around 30 million people at this time was rural — but of course that includes artisans, teachers, and priests as well as people working the land.4 Another rough estimate placed more than half the French workforce in the agricultural sector in the 1830s, two decades after our place in the narrative, and this figure was doubtless higher during the early years of the Restoration.5 Whatever the precise number of peasants, though, we’re talking millions upon millions of them.

Jules Breton, “Fin du travail (The End of the Working Day), c. 1886-7. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The land

Perhaps the most important factor for determining how good your life was as a French peasant was whether you owned your own farmland. If you did, then you could keep a larger share of the crops you grew, making everything easier.

And despite the popular image of peasants as serfs, bound by law to work their lord’s land, lots of Restoration-era French peasants did own their own land. This varied from region to region, with figures ranging from less than one-third to more than three-quarters in different departments. The overall figure seems to be less than half, however.6

This had been increased by the French Revolution, during which many better-off peasants used their savings to buy land seized from nobles or the Catholic Church. By 1802 peasants owned some 42 percent of French land. But even before the Revolution, peasants owned perhaps one-third of French land.7

But when we talk about peasants owning land, don’t get be thinking of U.S.-sized farms, where 40 acres is sometimes seen as a minimum viable size. In some of the better-off areas of France, typical peasant-owned farm plots were 10 to 20 acres, or 4 to 8 hectares.8 Poorer parts of France were much worse off, such as one impoverished region of western France where 63 farmers divided up 114 cultivable acres — that’s 1.8 acres or 0.72 hectares per person. And that’s just an average — only 16 of those 63 owned at least 2 acres of farmland. Many owned little more than a simple garden, referred to as a pièce de terre or “piece of land.”9

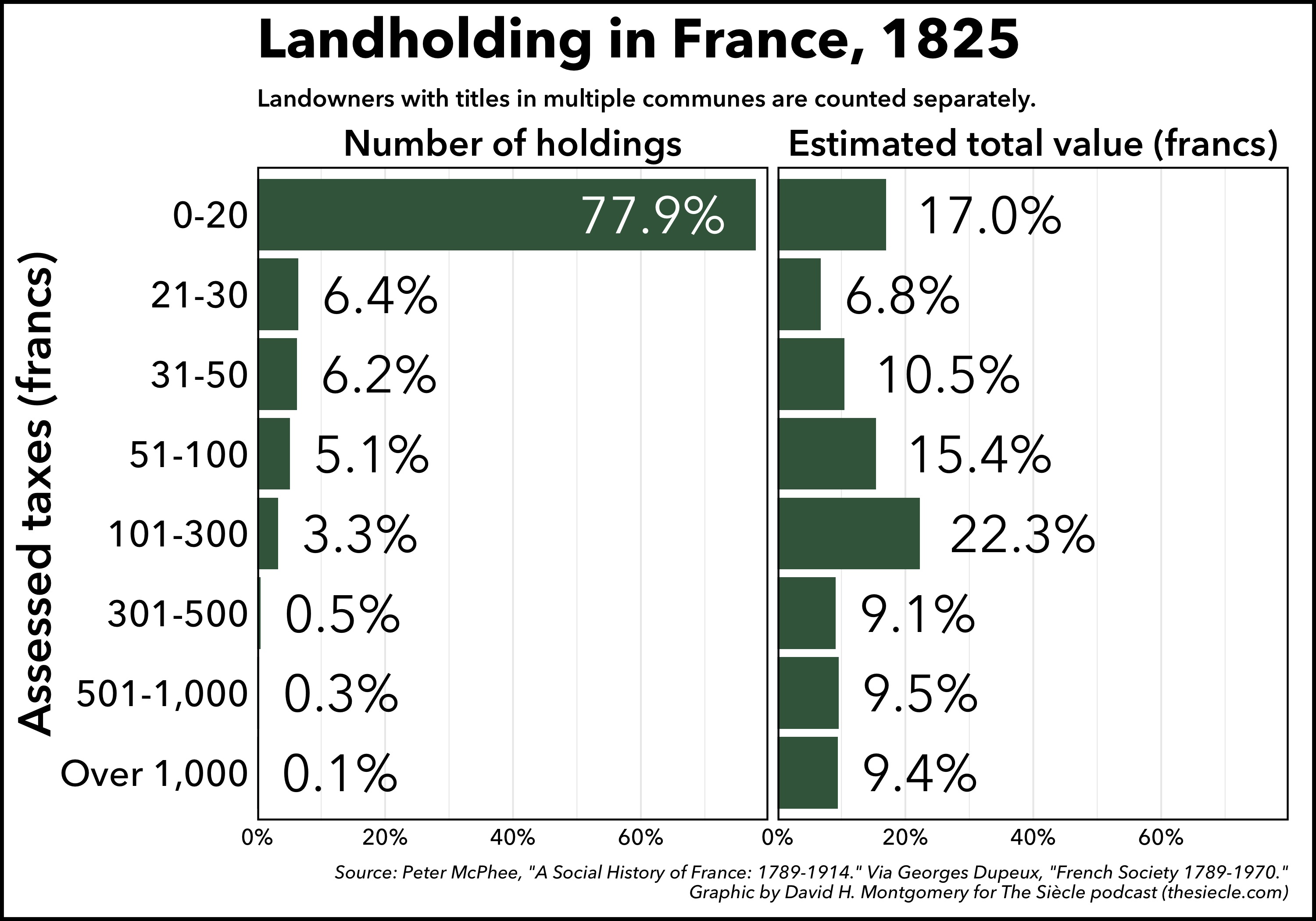

France was a highly unequal country. Contemporary tax rolls tell us that nearly 80 percent of all landholdings in the country were taxed in the smallest bracket, accounting for just 17 percent of France’s land value. Meanwhile the top 0.4 percent of landholdings were worth nearly 19 percent.10

Visit thesiecle.com/episode10 to view a chart I made showing the full breakdown of Restoration France’s land inequality.

Survival

So how do you survive on a two-acre plot of farmland?

The answer is that lots of “subsistence farmers” weren’t actually subsistence farmers — or at least, not only. A few acres of land won’t produce enough food to feed a family, certainly not in a bad year. So even peasants who owned their own land also did a range of other work to make ends meet.

A typical peasant family might farm a small plot of an acre or two, and rent another small plot from someone else to supplement their yield. In addition to helping out with the farming, the wife would work in the home, spinning or sewing clothes to sell on the market. The husband would work part-time as a day laborer for other landowners, or pursue a part-time craft like making clogs. Children would start working in earnest around age 1211 — schools were available in many peasant communities, but often too expensive or too far away for peasant families even if they could spare the children’s labor. As historian Eugen Weber notes, “for the poor and for those who clung to the old style of cultivation, children were still hands, hence wealth.”12 Finally, everyone in the family might do a little foraging — legally or not — for food, wood and other supplies in nearby wild areas, or sometimes their neighbor’s property!13

Jean-François Millet, “Buckwheat Harvest: Summer,” c. 1868-1874. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

All this could help a peasant family get by, but there was rarely much margin if things went wrong. Rather than getting into bushels of wheat or something like that, I’ll give some examples using money to help clear things up. As we’ve seen, even subsistence farmers in 19th Century France earned and spent money on top of their farming.

As a baseline figure, we’re told that in one town, a family of four needed 500 francs per year to avoid having to beg for food.14 Other figures in other areas are slightly smaller or larger, but we’ll go with that for now. Growing your own food could help with that, of course — maybe even cover all of that, if you were one of those lucky peasants with sizable holdings. But what if you were one of the vast numbers who owned nothing at all, or less than two-tenths of an acre?

Well, if you went out to work on your neighbors’ farms as a day laborer, you could probably earn about a franc a day, maybe 1.1 or 1.2 francs per day. And of course the problem of day labor is that there isn’t always labor every day. One estimate has dedicated day laborers being able to get perhaps 250 days of work per year, and earn between 250 and 300 francs.15 Hopefully you don’t get sick or hurt!

If you knew a skill or craft, you could do a little better for yourself than farm labor. For example, a man who made clogs might earn as much as 1.5 francs per day making and selling his wooden shoes to local dealers16 — though this extra money came with extra headaches, like how to get the voluminous supply of wood you needed.

Women, as was standard in the 19th Century, were explicitly paid less for their work than men. While a man might earn 1.5 francs per day carving wooden shoes, his wife working spinning wool could earn a pitiful 20 centimes, or .2 francs. Little wonder that in some areas, we’re told the “spinning wheel was often associated with begging.” But even pitiful wages might make the difference between a family starving or not.17

If a woman was skilled with a needle, she could do somewhat better — glove-makers could earn 50 or 65 centimes per day, serving the Paris fashion market, and were also in a better position to negotiate with the middlemen who bought peasants’ products and resold them to their final customers. Little wonder that over the course of our century, rural spinning will decline and glove-making and other skilled women’s crafts will rise. This didn’t just benefit women financially, but it also had an unexpected side effect: the needle and shuttle used in glove-making were much quieter than the noisy spinning wheel, which made a difference for the communal workspaces that peasant craftswomen, like craftsmen, usually operated in. “Silence,” historian Alain Corbin writes, “made conversation easier and liberated feminine speech.”18

Below: Jean-François Millet, “The Reaper,” 1866-7. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In good years, all this work plus whatever food you were able to grow on your own land or produce from animals you owned would keep your family fed, and even give you a little left over to buy non-essentials. Some peasants were able to accumulate assets to acquire new land and improve their situation. But over the long run, most households “were unable to acquire or rent enough land to sustain their members, even with textile work.”19 This would lead many peasants to relocate to the cities — though that is a story for a future episode.

By way of comparison, a rural priest might earn anywhere from 500 to 1,500 francs per year (and most Restoration-era priests came from the countryside, not cities).20 If a village had a teacher, they might earn 500 francs a year or less, and much of that from tuition, such as the village where those locals rich enough to afford 1 franc per month per child would send them to school.21 In some area, wages could be higher, such as textile workers near Lyon who earned 2 to 2.25 francs per day in 1820, or Paris artisans who could earn 3.25 francs per day for a carpenter, 4.5 for a roofer or 5 for a locksmith, though higher prices often accompanied higher wages.22 Meanwhile a typical noble family might earn 5,200 francs per year from their estates,23 with holdings bringing in just 3,000 francs considered “tiny.”24 Some nobles, of course, earned many times more than that.

It’s also worth noting that for all this talk of francs and peasants’ connection to the market economy, all of which is real, evidence suggests many peasants “avoided cash transactions whenever possible,” preferring instead to pay in kind, by bartering or exchanging favors, though the evidence is equally clear that cash did circulate in peasant communities.25

Jean-François Millet, “Shepherd Tending His Flock,” early 1860s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Eating

So how much food did typical peasants manage to produce or buy with these meager earnings? The sad answer is not very much.

The median daily calorie intake in early 19th Century France was around 2,000 calories per person, well below what an active manual laborer needs.26 And remember that that’s an average — many people got less than that.

Here’s what that might look like for a typical family, via historian Christine Haynes, who I interviewed in Episode 6:

To sustain themselves for their strenuous work, peasants relied mainly on bread, as much as a kilogram per person per day, baked at home. This staple was supplemented with boiled porridge, vegetable soup (seasoned with lard), greens and roots, and (only after the late eighteenth century or so) potatoes; meat, especially beef, was a rarity reserved for illness and holidays. To drink, peasants had only water — which they usually had to haul from a fountain — or cider, rarely wine or even coffee.27

This general picture varied from region to region.28 In eastern France, for example, dwellers in mountainous regions often ate a “meagre diet of ’mixed’ bread, lentils, ‘séret’, the residual whey of their cheese production, a little salt pork and smoke-cured meat, not forgetting the berries gathered in the forest.” Down in the lowlands, where the soil was better, peasants ate better, but not by much — here again it was the standard bread, porridge and soup with lard.29 In northern France, potatoes were a bigger part of the diet, and beer sometimes joined cider as a staple drink.30 To the west,

The peasant of Maine usually lived in a dark hovel, baked a coarse bread every week, drank a sour cider, and filled up with soup. The peasant of Anjou was not housed much better, but his bread was often made of wheat, and he had vegetables, onions, broad beans, and cabbage to go with it.31

Salt was “scarce and dear, and treated like something precious.” One writer, growing up a few decades after Napoleon, recalled eating “rye bread soaked in salt water with a thimbleful of butter on it, morning noon and night, with a piece of dry bread after and, on feast days, an apple or a piece of cheese.” The bread was soaked because it was often exceptionally stale; while the Maine peasants typically baked bread every week, in other areas bread was baked as seldom as “every six or twelve months”:

In the Romanche valley, between Grenoble and Briançon, Adolphe Blanqui found villages so short of fuel that they used dried cow dung to bake their bread and prepared the loaves only once a year. He himself saw in September a loaf he had helped begin in January. That sort of bread had to be cut with an axe, a hatchet, or an old sword, and you could not count yourself a man until you had the strength to cut your own bread when it was stale and hard.32

Even peasants who made wine rarely had enough of a surplus to drink it, such as the small vintners of the Loire Valley, who “only tasted their wine on special occasions.” 33

Health

Unsurprisingly, getting less than 2,000 calories per day of bread and soup wasn’t great for peasants’ health.34 Contrary to any images you might have about strong, hearty peasants, the reality was often quite the opposite. In 1820s France, “about a quarter of boys liable for [military] conscription were refused as being below the minimum height to handle a musket.” That minimum height was just over 5 feet, or 153 centimeters. And the highest rates of stunted, malnourished young men were in rural areas, not Paris or the new, smoky factory towns.35

Eugen Weber gives some specific examples from the department of Lot in southwestern France; in one district, the 1830 draft class consisted of 1,051 draftees, of which 212 (one-fifth) were rejected. Of those, the cited reason was stuntedness (défaut de taille) for 120. Consistently, Weber notes, up to half of all people rejected for military service were rejected for shortness. Many of the others had various physical deformities or ailments, which are also associated with malnourishment.

In 1860 one rural area near Grenoble had this to show to the army recruiters: goiter, 140; deaf or dumb, 13; lame, 13; myopia, 36; tapeworm, 19; scabies, 1; skin maladies, 86; scrofula, 15; epilepsy, 2; general weakness, 197; hunchback, 29; bone distortion, 2. In a total of 1,000, 553 men were disqualified, only 447 found fit for service.36

Alain Corbin’s case study of a peasant born in 1798 notes he was 5’5”, or 165 centimeters tall and that “for this time and place, in other words, he was a tall man.”37

Jules Jacques Veyrassat, “Chevaux au labour.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

All that said, the Restoration was actually not a bad time to be a peasant farmer — compared to the recent past. From the 1780s to the 1820s, French life expectancy soared by about a decade — from about 28 years before the Revolution to about 39 years after it. The stunted peasants of the Restoration were still taller on average than their fathers had been. The improvement is a direct result of the Revolution, which removed the old “feudal dues” by which most peasants, even those who owned their own land, had to turn over significant shares of their harvest to their local lord. In much of France, feudal dues amounted to around 20 percent of the harvest. Now, peasants had a bigger surplus, some of which they ate and some they used to diversify from wheat into more profitable forms of agriculture, like grapes or cattle.38 It’s no surprise that peasants could be vigilant for any attempt to restore the feudal dues or the old 10 percent tithe that used to be exacted for the Catholic Church.

Technology

Another important factor in understanding the poverty of 19th Century French peasants has to do with technology — though as we’ll see, the story here is more complicated than it might seem.

Contemporary commentators frequently pointed out the technological backwardness of French peasants, who didn’t use modern tools and techniques to farm their small plots of land. In many cases they weren’t even using medieval tools and techniques.

Below: Jules Breton, “The Shepherd’s Star,” 1887. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

For example, many peasants were observed to harvest their crops with a sickle. That’s a hand-held tool with a hooked blade used for harvesting crops. You’ve probably seen it on the Soviet flag, and can see some pictures of peasants using them at thesiecle.com/episode10. Sickles are a technology dating back tens of thousands of years, and are effective at what they do — but not nearly as effective as the scythe, the long-handled, two-handed cutting implement used in stereotypical depictions of Death to harvest souls. The scythe was in general two to three times faster than the sickle at harvesting wheat, and yet many peasants stuck to their trusty sickles.39 Farmers also often stuck to traditional techniques involving letting fields lie fallow every three or even every two years — a traditional way to keep from exhausting the soil, but one that was increasingly unnecessary with fertilizer or more modern agricultural techniques that had the advantage of not wasting a third of your farmland every year.40

For example, many peasants were observed to harvest their crops with a sickle. That’s a hand-held tool with a hooked blade used for harvesting crops. You’ve probably seen it on the Soviet flag, and can see some pictures of peasants using them at thesiecle.com/episode10. Sickles are a technology dating back tens of thousands of years, and are effective at what they do — but not nearly as effective as the scythe, the long-handled, two-handed cutting implement used in stereotypical depictions of Death to harvest souls. The scythe was in general two to three times faster than the sickle at harvesting wheat, and yet many peasants stuck to their trusty sickles.39 Farmers also often stuck to traditional techniques involving letting fields lie fallow every three or even every two years — a traditional way to keep from exhausting the soil, but one that was increasingly unnecessary with fertilizer or more modern agricultural techniques that had the advantage of not wasting a third of your farmland every year.40

But while 19th Century observers loved to rag on the stupid, hidebound peasants whose stubbornness kept them poor, a closer examination complicates any such attempts at judgment. For one, of course, new equipment costs money that many peasants didn’t have, or might prefer to save for new land or to buy food if their harvest failed. Buying fertilizer to avoid letting a third of your fields go fallow might pay off in the long run, but you have to pay for the fertilizer up front — and that’s if the Restoration’s woeful transportation infrastructure could even get it to your farm.41 Meanwhile the new tools were more complex, which often meant peasants couldn’t repair them at home any more — they had to pay someone else to refurbish their tools.42

Finally, whatever the benefits of these technological upgrades — and they were real — it was rarely just a matter of swapping out tools. Farming is an entire system involving crops, tools, techniques and more, all of them intertwined. So farmers who were expecting to use the sickle to harvest their crops planted those crops in a way to optimize harvesting with the sickle. So switching from a sickle to a scythe isn’t just a way to speed up your harvesting — you might have to change up your entire method of farming. For example, much later in the 19th Century, some peasants will cling to their sickles and old-fashioned plows as a package deal. The plows created so-called “raftered fields,” with two plowed furrows forming a ridge that’s easily harvestable with a sickle but tricky with the much larger scythe. Switching to a better plow would have eliminated the ridges, requiring the peasants to learn two new tools instead of one. But changing how the field is plowed also changes how it drains. So a simple decision to switch to a new harvesting tool, or a new plowing tool, has far-reaching impacts.43

It’s all very well for a rich farmer to experiment with new technologies — they’re not going to starve if the transition proves rocky. But a peasant who was on the verge of begging to begin with has little leeway for experimentation.

Disaster

Even today, with industrial machines, fertilizer, computer models, weather forecasts and the like, farming is a highly imprecise art, with yields varying wildly from year to year. Imagine how it was for pre-industrial peasants using wooden plows and sickles. As we discussed earlier, it was all that many peasants could do to just scrape by each year. But what happens when the weather turns against you and the harvest is bad?

This wasn’t just an occasional phenomenon in Restoration France. “On average,” historian Peter McPhee notes, “one year in four the size of crops failed to allow what today would be termed a minimum calorific intake.”44 McPhee was speaking primarily about the years before the Revolution there, but even during in the years following 1815, harvest failures remained common.

So when the harvests did fail — when there was not enough rain, or too much, or hail, or insects, or early frosts, or any number of other causes — the simplest answer is that people died. Around 1820, the French death rate was around 2.5 percent; that shot up during famine, especially for infants and the elderly or sick], as people cut back the food they ate. Birth rates also plummeted, in part because of malnourished women miscarrying. Then, once the crisis had passed, birth rates would shoot up again as young people pulled the trigger on delayed marriages.45

To make the reduced food supply last, peasants would go to unappetizing extremes. In 1812, one government official wrote about how “a considerable number of indigents have been forced to eat bran and some rather disgusting herbs, and they felt happy when they were lucky enough to add a little butter or cheese to this not very nutritious mixture.”46

When times got tough, peasants would often turn to begging. If they were lucky, they could turn to their networks of family and friends for assistance. If not, they could try their neighbors — who were often willing to help out. But when neighbors weren’t, starving people didn’t always let that stop them, especially when they felt the food they needed was being unjustly taken away.

For example, during famines, Parisians would pay inflated prices to buy what food was available to prevent starvation in the capital, and bands of “outlaws” would try to intercept the wagons and take the grain for local villages.47 In 1802 we’re told of a band of women, backed by men with pitchforks and muskets, who stopped a merchant’s cart and “forced him to sell thirty loaves of bread at a price they set.” Those peasants who were lucky enough to have food might simply find themselves the victims of these who didn’t.48

To prevent this kind of disorder, the authorities set up relief measures, including buying and distributing food, and setting up charity workshops where indigents would be confined and given food in return for work. They’d also try to coordinate and encourage private charity, which — especially in the early part of the 19th Century — was often much more significant than government assistance in rural areas. Some of this was organized through soup kitchens, but in many areas both donors and recipients preferred their charity to be informal and spontaneous.49

These relief efforts, formal and informal, private and state-run, were all just attempts to treat the symptoms after the fact. The fundamental reality was that crop yields for most peasants weren’t high enough to handle the drop in a bad year, and suffering often followed.

Next time on The Siècle, we’re going to examine this in action, at one specific harvest failure: the harvest of 1816, which has major cultural and political impacts in addition to the human cost. Be sure to visit thesiecle.com for transcripts, sources and more, including plenty of paintings of 19th Century French peasants. My thanks for listening and for spreading the word about the show to your friends, on social media, and by rating and reviewing it on iTunes. Join me in two weeks for Episode 11: The Year Without A Summer.

-

This entire episode is adapted in part from a presentation given at a “Nerd Out” event hosted by “Nerds of the Twin Cities” on May 9, 2019. ↩

-

Technically our word comes from the Medieval French païsant, rather than the modern form paysan. ↩

-

Eugen Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870-1914 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1976), x-xi. ↩

-

Peter McPhee, A Social History of France: 1789-1914. 2nd ed. (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 147. ↩

-

François Caron, An Economic History of Modern France, translated by Barbara Bray (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979),32-3. A vast “rural exodus” had already begun by the Restoration, though it would greatly accelerate in future decades. Caron, An Economic History, 121-5. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 148. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 148. McPhee, A Social History of France, 10. ↩

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 210, 282, 314, 319. ↩

-

Alain Corbin, The Life of an Unknown: The Rediscovered World of a Clog Maker in Nineteenth-Century France, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 29, 30. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 147 ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 73. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 176. ↩

-

Corbin gives numerous examples of legal disputes between peasant neighbors in the Perche region of France, including a case where one man took manure from another’s field, a case where one man fished in another pond, and innumerable cases involving damage to, or inappropriately erected, fences and hedges. Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 109-116. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 93. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 165. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 86. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 90. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 90-92. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 153-4. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 154. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 163. Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 57-9. Note: Due to an error, this text originally said a teacher earned 500 francs per month, not year. Corrected on Jan. 7, 2024. ↩

-

Guillaume De Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 250-1. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 103. ↩

-

Honoré De Balzac, Père Goriot, translated by Burton Raffel (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994), 26. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 106-8. ↩

-

David R. Weir, “Parental Consumption Decisions and Child Health During the Early French Fertility Decline, 1790-1914” (The Journal of Economic History 53, no. 2 (1993)), 259-74. ↩

-

Christine Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies: The Occupation of France After Napoleon (Cambridge, Mass., and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2018), 53. ↩

-

What follows is taken from an answer I previously wrote for Reddit’s AskHistorians forum. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 324-5. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 338. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 227. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 136. Some of these observations were still being made well into the second half of the 19th Century. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 355. ↩

-

Much of what follows is adapted from an answer I previously wrote for Reddit’s AskHistorians forum. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 176. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 150-1. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 53. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 99-100. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 123-4. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 212-3. McPhee, A Social History of France, 158-9. Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 120-4. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 121-2. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 123. ↩

-

Weber, Peasants Into Frenchmen, 125-6. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 15. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 15. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 166. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 15. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 165, 168. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 164-9. ↩