Episode 20: The Death of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte died on Saturday, May 5, 1821. He was 51 years old, and had not set foot in France for more than six years. The former Emperor of the French, and First Consul of the French Republic, and King of Italy, the foremost general of his age, the man around whom a continent had revolved for most of a generation, died in agony half a world away from his former conquests, in exile on the British island of St. Helena.

Napoleon had been sent to remote St. Helena in the hopes that he would be forgotten, and after news of Napoleon’s death reached Europe, some people let themselves think it had worked. The diplomat and quip machine Talleyrand, for example, rebuked a companion who described Napoleon’s death as a great event. “It is no longer an event,” Talleyrand supposedly responded. “It’s just a piece of news.”1

But while the emperor’s body was buried beneath a nameless grave in the South Atlantic, his memory was assuredly not dead. Napoleon himself had helped see to that over his final years, which were as productive for his legacy as they were miserable for the man.

This is The Siècle, Episode 20: The Death of Napoleon.

The exile

Four days after Waterloo, Napoleon abdicated as Emperor of the French for the second time. His intent, as foreign armies closed in and his domestic political support collapsed, was to move to the United States. “If I had gone to America,” Napoleon later mused, “we might have founded a State there.”2

Unfortunately for Napoleon, the vigorous action that had secured him so many of his great victories seemed to desert him at this last moment of need. Rather than dart to the coast after his June 22 abdication, he spent three days in Paris, then another four days at his ex-wife Josephine’s former home in the Parisian suburbs, concerned with such formalities as applying for a passport from France’s provisional government. When he finally reached a port on July 2, he found a British ship of the line blockading the harbor, and waited there for 12 days while trying to figure out a way to slip past it. Along the way he passed up opportunity after opportunity, including hesitating when his brother Joseph showed up and offered to exchange identities with him.

Instead, as Napoleon dawdled, Louis XVIII formally retook control of the French government, removing the minor resources that the provisional government had offered to help Napoleon leave the country. Meanwhile soldiers from Prussia were spreading out across France. Both the Prussians and Bourbons would probably have executed Napoleon, had they captured him.3

Having wasted all his other chances, Napoleon finally took his last, best option: he surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of the HMS Bellerophon, the British ship that had prevented Napoleon’s escape for nearly two weeks. Britain had fought Napoleon more determinedly than any county in Europe, but it was also a constitutional monarchy, and so, as Napoleon wrote in a letter of surrender, “I put myself under the protection of its laws… as the most powerful, the most constant and most generous of my enemies.”4

Above: William Quiller Orchardson, “Napoleon on Board the Bellerophon,” c. 1880. This depicts the morning of July 23, as the Bellerophon sails away from France with its new prisoner on board. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Below: Charles Lock Eastlake, “Napoleon Bonaparte on Board the ‘Bellerophon’ in Plymouth Sound,” 1815. Eastlake was actually on board at the time and sketched Napoleon, from which he later painted this. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In one sense, Napoleon had made a savvier decision than he might have recognized. Britain’s government remained implacably against him, but the British people were fascinated by the French emperor who was suddenly in their custody. Captain Maitland wrote that he was surprisingly “prejudiced in favor of one who had caused so many calamities to his country.” When the Bellerophon pulled into Plymouth harbor, news quickly leaked out that Napoleon was on board, and soon thousands of people were flocking to the area, lining the beaches and putting out into the harbor in whatever boats they could hire to try to catch a glimpse of the former emperor.5 One eyewitness, a student named John Smart, recalled that “all the country seemed to come in. Gentlemen and ladies came on horseback and in carriages; other people in carts and wagons; … to judge by the number of people, all the world inland was flocking to see Bonaparte. The Brixham boatmen had a busy time of it, and must have taken more money in in two days than in an ordinary month.”6

In one sense, Napoleon had made a savvier decision than he might have recognized. Britain’s government remained implacably against him, but the British people were fascinated by the French emperor who was suddenly in their custody. Captain Maitland wrote that he was surprisingly “prejudiced in favor of one who had caused so many calamities to his country.” When the Bellerophon pulled into Plymouth harbor, news quickly leaked out that Napoleon was on board, and soon thousands of people were flocking to the area, lining the beaches and putting out into the harbor in whatever boats they could hire to try to catch a glimpse of the former emperor.5 One eyewitness, a student named John Smart, recalled that “all the country seemed to come in. Gentlemen and ladies came on horseback and in carriages; other people in carts and wagons; … to judge by the number of people, all the world inland was flocking to see Bonaparte. The Brixham boatmen had a busy time of it, and must have taken more money in in two days than in an ordinary month.”6

John James Chalon, “Scene in Plymouth Sound in August 1815: The Bellerophon with Napoleon Aboard at Plymouth (26 July - 4 August 1815),” 1817. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At this stage, Napoleon hoped that the British might sentence him to an exile at an English country house. But these hopes were soon to be dashed. The scenes in Plymouth harbor reinforced the British government’s fear that if Napoleon were kept in Britain, he would become “an object of curiosity” and also serve by his proximity to influence and destabilize Louis XVIII’s restored government in France. So the British rejected proposed prisons such as Scotland or the Tower of London in favor of the most remote place they could think of: the island of St. Helena, more than 1,000 miles or 1,800 kilometers from the coast of Africa and more than 2,000 miles or 3,200 kilometers from the coast of South America.7

A possession of the East India Company used as a resupply stop on the sea route to the East, St. Helena was judged the “place in the world best calculated for the confinement of such a person,” especially after Napoleon had previously escaped so easily from the island of Elba, with its proximity to southern France. The British cabinet decided on July 21 to send Napoleon to St. Helena, and formally informed the former emperor of his destination on July 31. He did not take the decision well, berating the dignitaries who had delivered the news and insisting that rather than go to St. Helena, “I prefer death.”8

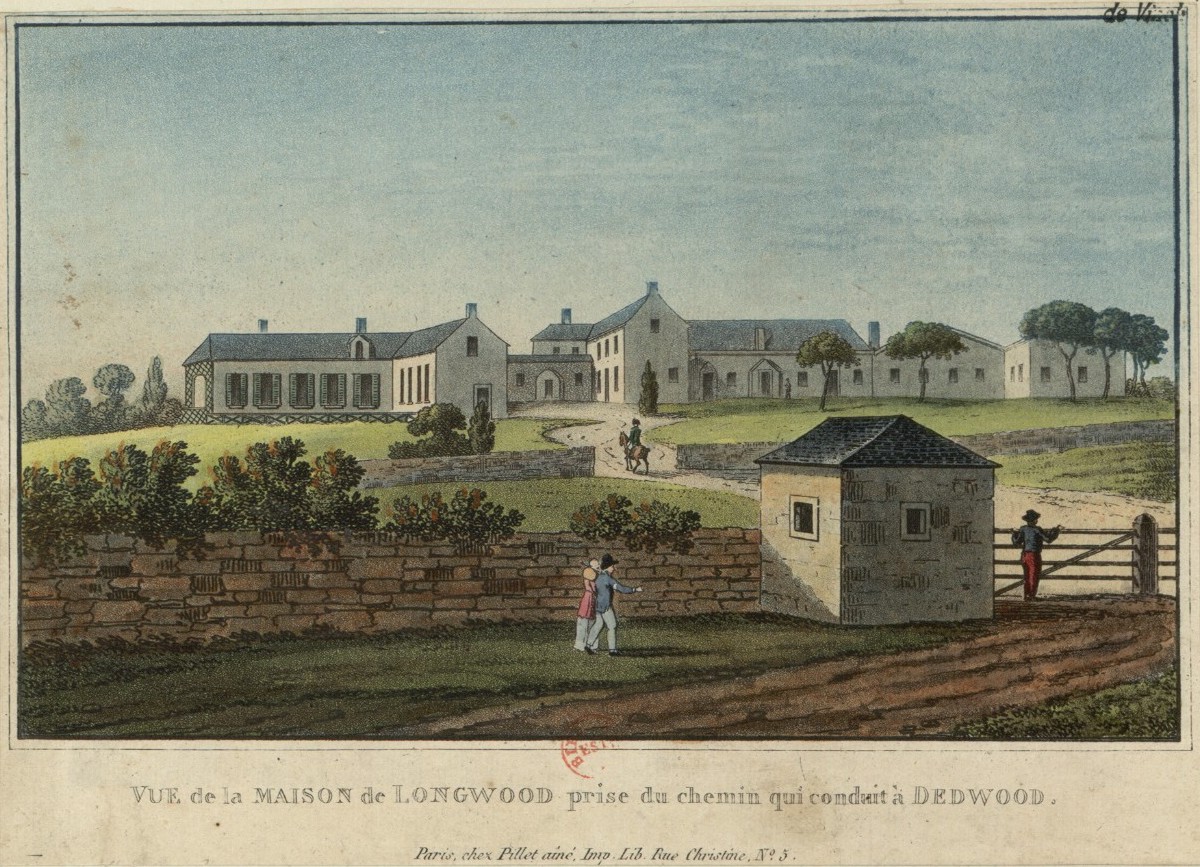

One of Napoleon’s principal objections to St. Helena, aside from its isolation, was the island’s climate, which he insisted was unhealthy. This would have surprised British officials such as the Duke of Wellington, who had visited St. Helena on his trip home from India in 1805, and called its climate “apparently the most healthy I have ever lived in.” But Wellington and other British officials had mostly stayed in Jamestown, the island’s principal port, which has a dry, mild climate, today seeing 4.5 inches of rain per year and average high temperatures in the 70s and 80s Fahrenheit year-round.9 Napoleon was destined for an estate called Longwood, on a plateau in the center of the island, which has a unique micro-climate very different from Jamestown, 4 miles or 6 kilometers away. In contrast to dry Jamestown, Longwood is intensely humid, with cloudy skies 300 days per year, and relative humidity regularly at 100 percent. At Longwood, “Napoleon’s playing cards had to be dried in the oven to stop them sticking together.” It also was infested with all sorts of vermin, including termites, mosquitoes, cockroaches and rats, the last of which were allegedly “so thick on the carpet that it appeared black,” and swarmed over anything edible left unattended for more than a few seconds.10

Anonymous, “Vue de la Maison de Longwood prise du chemin qui conduit à Dedwood” (View of the House of Longwood from the path to Deadwood). Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Memoirs of St. Helena

Napoleon Bonaparte landed on this island on October 15, 1815, after a sea journey of several months. It was to be his prison and his tomb, and the site of his reinvention.

He had fled Europe ignominiously, after military defeat forced him to abdicate his throne for the second time in as many years. A decade-plus of propaganda, soon to be reinforced in France by works funded by the restored Bourbon monarchy, had spread what Napoleonic scholars dub the “black legend”: that Napoleon was a cruel, depraved tyrant, devoid of virtue and possessed of every manner of moral and sexual perversion. As Napoleon’s biographer Philip Dwyer puts it, “He was variously portrayed as a Corsican brigand; as an exterminator of men; as Apollyon, the [similarly pronounced] angel of the Apocalypse; as Nero, Attila, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane; as a cruel tyrant.” One enterprising polemicist engaged in some creative numerology to calculate that the letters in Napoleon’s name added up to 666.11

Anonymous, “Proposition de Constitution aux Habitans de l’ile de St Hélène par l’Ex Empereur et Roi,” 1815. This Bourbon caricature mocks Napoleon as a liar and buffoon. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

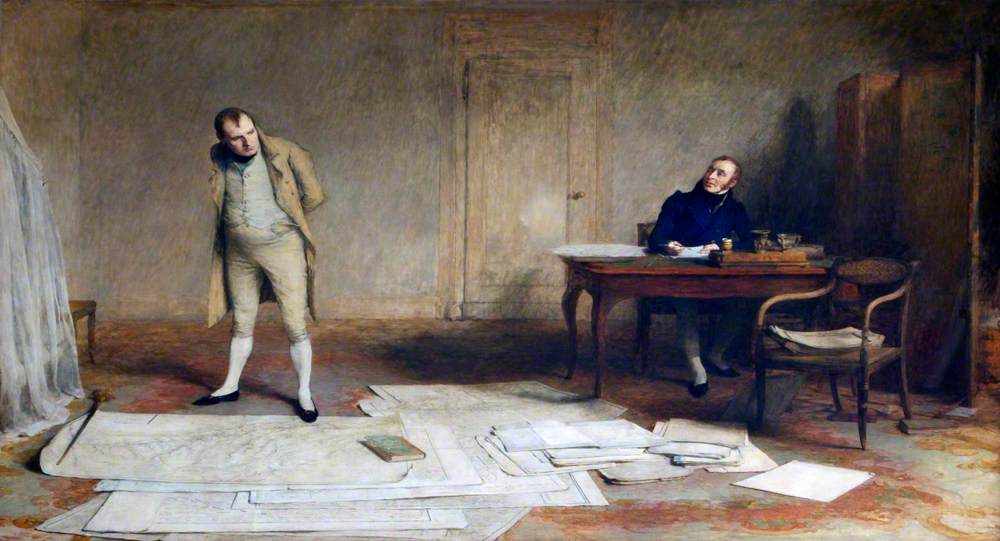

But upon arriving in St. Helena, an exiled prisoner, the emperor had all the time in the world to strike back. Napoleon’s weapon of choice? The memoir. On St. Helena, Napoleon eventually settled into a routine: after breakfast around 10 a.m., he would meet with an aide to dictate his memoirs. While dictating, Napoleon would pace up and down the room, head down and hands behind his back, speaking in a flurry of rapid French for his aides to transcribe. Despite the speed at which he talked, Napoleon hated being interrupted, “no matter how incoherent his thoughts were.” Later, he would go over the notes and make corrections and revisions.12 At times, while relating his memories of his military campaigns, Napoleon would lay maps all over his billiard table, holding them open with billiard balls. A visitor once asked him how he could recall so many minute details, to which Napoleon responded, “Madam, this is a lover’s recollection of his former mistress.” Of course, much like many other memorists and ex-lovers, Napoleon embellished, omitted, and outright lied throughout his memoirs, which were intended to rebuild and defend his reputation, not be some sort of objective history. “The historian, like the orator, must persuade, he must convince,” Napoleon said.13

It’s beyond the scope of this podcast to go into precise details about what exactly Napoleon embellished and lied about in his memoirs. What’s important for our purposes is the new image Napoleon created, or emphasized, of himself in these memoirs. The Napoleon Bonaparte that emerged from his books, and the numerous memoirs published by his aides on St. Helena, cast him as a genius, a patriot, a liberal, and a peacemaker who had been repeatedly forced into wars he didn’t want by France’s enemies.14

William Quiller Orchardson, “St. Helena 1816: Napoleon dictating to Count Las Cases the Account of his Campaigns,” 19th Century. Emmanuel-Augustin-Dieudonné-Joseph, comte de Las Cases, accompanied Napoleon to St. Helena and wrote the most famous memoir from the island, the “Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène” or “Memorial of St. Helena.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The various parts of this new Napoleonic image had widely varying relations to the truth. Some of them even conflicted with Napoleon’s own past propaganda. For example, before his first abdication in 1814, Napoleon had “portrayed himself as primarily a strong charismatic ruler and as a military conqueror.” But after the Hundred Days, Waterloo and his second abdication, Napoleon and his supporters cast the emperor as the “upholder of the Revolutionary principle of equality” and “the potent symbol of liberty.”15

This wasn’t totally out of the blue. While Napoleon in his prime had been autocratic, you might remember in Episode 2 that during the Hundred Days, Napoleon had cast a very liberal tone, promising reform, and asking the liberal philosopher Benjamin Constant — who we’ve seen repeatedly pop up as a parliamentary leader of the liberal opposition — to write a new constitution that abolished censorship and transformed the Empire into a constitutional monarchy. Historians debate how much Napoleon would have abided by these liberal promises had he remained in power. Unfortunately for Napoleon, but fortunately for his legacy, Napoleon never got the chance to backslide. So when his memoir cast him as a champion of liberté and egalité, the claims weren’t as far-fetched as they would have been in 1814. Still, this hagiographic view of Napoleon, put out by the man himself and his supporters, has been dubbed the “golden legend,” in contrast to the “black legend” I discussed earlier.

Franz Josef Sandmann, *Napoléon in Sainte-Hélène, 1820. Note that while evocative, Napoleon’s estate of Longwood was at the center of the island, and he never stood and stared out to sea as this painting depicts. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.*

Golgotha

Below: Jean Mathias Fontaine, “Sir Hudson Lowe,” c. 1830, with Lowe’s signature. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

But revisionist propaganda wasn’t the only way that Napoleon’s time on St. Helena remade his image. It also helped turn him into an object of popular sympathy. And here I need to finally introduce Hudson Lowe.

But revisionist propaganda wasn’t the only way that Napoleon’s time on St. Helena remade his image. It also helped turn him into an object of popular sympathy. And here I need to finally introduce Hudson Lowe.

Sir Hudson Lowe arrived on St. Helena on April 14, 1816, 183 days after the arrival of the island’s most famous resident. Lowe was a major-general in the British army who had fought the French all across Europe. Now he was chosen for the highly sensitive task of being the governor of St. Helena — or, to put it more bluntly, of being Napoleon’s jailer. He was 46 years old, and was chosen for the job after another candidate was rejected for being too conciliatory.16 That alone should give you a pretty good idea of Lowe’s personality. A Russian diplomat assigned to St. Helena complained that Lowe was “fussy and unreasonable beyond all expression. He gets along with no one and sees only betrayal and traitors.” An Austrian diplomat called Lowe “empty,” “muddled,” “narrow-minded” and “unbalanced.” And these were from allies, who shared Lowe’s goal of keeping Napoleon contained!17 You can only imagine how Napoleon and his entourage saw their jailer.

Lowe lived just a few miles away from Napoleon’s estate of Longwood, and yet only met his prisoner on six occasions, all within the first four months of Lowe’s arrival. For the rest of their five years together on St. Helena, the two waged an increasingly intense war of letters.

At the core of their dispute were three key issues. The first was the cost of Napoleon’s imprisonment, which quickly reached as high as £18,000 per year — the equivalent of well over one million pounds today. Napoleon had to be fed and housed, as did a staff of aides and servants allowed to him as a prisoner of social rank. The emperor’s entourage certainly lived well, with two formal meals per day and a stupendous amount of alcohol, much of it at British government expense. For one month, the estate of Longwood consumed a total of 1,859 bottles of alcohol, which amounts to multiple bottles per occupant per day. Even Napoleon, who drank less than the others, consumed half a liter of wine per day. Partly this reflects the habits of a more alcoholic age, but partly it reflected prisoners intent on maintaining a lifestyle similar to what they had lived as leaders of the greatest power in Europe. The British, understandably, weren’t keen on spending thousands of pounds to support the drinking habits of a bunch of Frenchmen, and so constantly tried to force Napoleon to economize.18

The second key issue was Lowe taking his directive to at all costs prevent Napoleon’s escape extremely literally. He had thousands of soldiers on the island, posted sentries around Longwood day and night, assigned officers to monitor Napoleon’s whereabouts at all times, and monitored Napoleon’s mail. There were, in fact, schemes concocted by various Bonapartists to break the emperor out, but none of them advanced very far, and Napoleon himself rejected all proposed escape attempts, such as hiding him inside a barrel of dirty laundry, as undignified.19 But Lowe and everyone else knew of Napoleon’s decades-long track record of daring naval escapes, and without the benefit of hindsight their rigorous precautions can make a certain amount of sense.

R. Cocking (from a sketch by C.I. Latrobe), “Distant view of Longwood, St. Helena,” 1818. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

By far the pettiest of the three major issues was the question of dignity. Put simply, Napoleon and his aides insisted that he was an exiled head of state who was due a certain degree of respect and honor. The British, who had never recognized Napoleon as Emperor of the French, saw no reason to change now. When one of Napoleon’s aides wrote a letter to a British admiral that referred to Napoleon as “emperor,” the admiral wrote back, “I have no cognizance of any Emperor being actually on the island.” Lowe refused to forward gifts to Napoleon that referred to him as an emperor. Similarly, Napoleon’s staff refused letters that were addressed simply to “Napoleon Bonaparte.” There were real issues here, of course — if Britain admitted Napoleon was an emperor, that might affect the legality of imprisoning him at all, and the propriety of imprisoning him at a place such as Longwood. Moreover, it was a matter of intense personal pride for Napoleon, who had once ruled most of Europe and was now reduced to a single estate; ceremony and dignity were all he had left, so he insisted on proper forms of address and a host of ceremonies, from servants in full livery to making visitors stand in his presence.20 But Lowe, a most inflexible man, refused possible compromises, such as the common early 19th Century expedient of referring to someone by a courtesy title. Napoleon proposed being referred to as “Colonel Muiron” or “Baron Duroc,” after the names of former aides, but Lowe refused. This petty and personal standoff would continue until the very end.21

Just how serious you consider this compilation of insults and deprivations is up to you. But in letters smuggled off the island, and in conversations with travelers passing through who were eager to meet with its famed prisoner, Napoleon played up his alleged torments as much as he could. The primary goal was to try to pressure Britain and the allied powers into making his imprisonment more comfortable and generous.

This failed, but not without accomplishing a secondary goal: engendering lots of sympathy and support in Europe for the man damned in official propaganda as a modern-day Attila. No less a figure than Pope Pius VII, who had himself been a prisoner of Napoleon, wrote a letter to Tsar Alexander of Russia protesting the conditions of Napoleon’s imprisonment.22

As part of this P.R. blitz, Bonapartists drew on mythological and religious metaphors, including the most powerful rhetorical weapon available in the early 19th Century: they compared the former emperor to Jesus. In Napoleonic propaganda, St. Helena was described as Napoleon’s Golgotha, after the site where Jesus was crucified. Napoleon himself told a British official, in 1817, “You have placed on my head, as it was with Jesus Christ, a crown of thorns, and by doing so, you have won me many partisans.”23

Anonymous, “Le Promethée de l’Isle Ste.-Hélène,” 1815. This French political cartoon shows Napoleon as Prometheus, the mythological figure who stole fire from the gods for humanity and was punished by being tied to a rock and having his liver eaten by an eagle for all eternity. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

If Napoleon was playing up his suffering, he was absolutely right about the effect these reported sufferings had on public opinion, as we’ll see.

Illness and death

But if you’re thinking that a refusal to call Napoleon “emperor” and trying to cut his entourage back to just a bottle or two of wine per day seems a little paltry basis for comparing him to Jesus on the cross, you’re not entirely wrong. That’s because there was another really important part of Napoleon’s exile on St. Helena that contributed to the narrative of his so-called “Passion”: his agonizing, painful death.

I’ll interject a note here that most of the rest of this episode is going to contain specific descriptions of medical symptoms suffered by Napoleon in the years leading up to his death, which could be disturbing for some listeners. If you think that’s not something you want to listen to, feel free to stop the episode, or skip to the last minute or two.

Hector Berlioz’s “Le cinq mai, chant sur la mort de l’empereur Napoléon,” 1835, was a setting of a poem by Pierre-Jean de Béranger about the death of Napoleon.

Napoleon’s first year on the island went well enough. He was reasonably active, going for walks or horseback rides, and working vigorously on his memoirs. But starting in October 1816, his doctor on the island, an Irish surgeon named Barry O’Meara, began to record symptoms of Napoleon’s ill health. It started with a “pale countenance” and bleeding gums, followed a day later by some difficulty breathing. In November he had swelling in his legs; the following March he reported “occasional attacks of nervous headaches”; in July his ankles were swollen again, and he reported difficulty sleeping and difficulty urinating. By October 1817, O’Meara noted pain in Napoleon’s side, an accelerated pulse and “excitable bowels,” and noted that if these symptoms continued, “there will be every reason to believe that he has experienced a bout of chronic hepatitis.”24

O’Meara may or may not have realized it, but he was on dangerous ground with his diagnosis of hepatitis. While today we use “hepatitis” to refer to a number of specific viral diseases affecting the liver, at the time it referred to liver disease in general, and in particular was believed to be caused by unhealthy climate. Since the British had imprisoned Napoleon at a place on St. Helena with an unpleasant microclimate, a diagnosis of hepatitis could mean that the British were directly responsible for Napoleon’s ill-health and possible death. So Lowe’s response to O’Meara’s medical reports was to forbid him from using the word “hepatitis,”25 an injunction that would continue as the emperor’s health continued to decline.

Early on, Napoleon treated his medical issues primarily by taking hot baths every afternoon, for between two and four hours at a time.26 This continued even after his health took a turn for the worse in 1818. Early in that year Napoleon didn’t step outside for a month, as his periodic leg-swelling, side-pains, headaches, heart palpitations and nausea began to intensify. With hindsight, most medical historians today see Napoleon as already suffering from the ailment that probably killed him: stomach cancer.

What exactly killed Napoleon has been the subject of considerable debate, not to mention conspiracy theories. But stomach cancer has always been the most likely culprit. His father Carlo Bonaparte probably died of the disease, at the age of 38; two of Napoleon’s siblings also likely died from stomach cancer, as did one of his illegitimate children.27 When the emperor’s body was cut open after his death, the lining of his stomach was found to be “to nearly its whole length… a mass of cancerous disease.” (Of course, a finding that his liver was “perhaps a little larger than usual” was struck from the final report by Lowe, for fear of suggesting the forbidden hepatitis diagnosis.) Suggestions that Napoleon might have been poisoned, while impossible to disprove, aren’t taken seriously by mainstream historians.28 The most solid argument against the cancer hypothesis is not a theory of arsenic poisoning, but that the immediate cause of Napoleon’s death was a gastric hemorrhage, though the cancer would have killed him eventually.29

What is indisputable is that Napoleon’s final years were agonizing. By July 1820, he suffered from constant stomach pains, regular nausea and frequent vomiting. He spent most of his time in his bed. He complained that the light hurt his eyes. On the rare occasions where he felt up for excursions, he tired frequently and often had to be taken back home in a carriage. In a pitiful coda to the life of the man who had once been master of Europe, during his final months the only form of exercise Napoleon could endure was playing on a see-saw which he had built in the billiard room, under the polite fiction that it was for the children staying at Longwood. Over the last decade of his life, Napoleon had become rather fat, growing from 67 kilograms or 148 pounds to 90 kilograms or 198 pounds. But during his final six months, Napoleon lost between 10 and 15 kilograms, or 22 to 33 pounds.30

Charles de Steuben (engraved by Jean-Pierre Marie Jazet), “Mort de Napoleon (5 mai 1821),” 19th Century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

After this long, painful decline, Napoleon knew he was dying in the early months of 1821. In March he left instructions for what his mother — who would outlive him by 15 years — was to be told of his death. In April he wrote a will, which was as much an aspirational and political document as a practical one, full of statements blaming his downfall on the treason of his associates, and clauses giving away items and money that Napoleon did not possess. Though by this point he had a dry cough, chills, and was vomiting blood, Lowe insisted to Napoleon’s last breath that the emperor was nothing more than a hypochondriac. On May 3, the man who had imprisoned a pope for years was given last rites. On May 4, he slipped into a delirium. And at 5:49 p.m. on May 5, Napoleon died.31

After his death, Napoleon lay in state in Longwood for first dignitaries and then ordinary residents of the island to view. His hair was shaved and distributed to Napoleon’s aides and family members; reliquaries with the emperor’s hair would soon be circulating around Europe as Bonapartist mementoes.32

The French on the island expected that Napoleon’s body would be returned to France for burial, but Lowe had some final cards to play. He announced that Napoleon’s body was to be buried on St. Helena. Like most of Lowe’s actions as Napoleon’s jailer, this was the result of direct orders he had received, not freelancing dickishness — but also like most of Lowe’s actions, he managed to turn it into a petty squabble. The old argument about Napoleon’s proper form of address reared its head when it came to the emperor’s tomb: the French wanted the gravestone to read “Napoleon,” his imperial title, but Lowe forbade it and argued for the more pedestrian “Napoleon Bonaparte.” In the end, the two sides were unable to agree, and nothing at all was inscribed on the slab.33

David Stanley, “Napoleon’s Grave on St. Helena Island,” 2014. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license.

Hudson Lowe was in many senses simply carrying out unpleasant orders, and he has been vilified by both contemporaries and subsequent historians for it. But even if he can’t be personally blamed for Napoleon’s unpleasant and acrimonious final years, it’s impossible to avoid the conclusion that Hudson Lowe made it easy for his detractors to vilify him.

We have, after all that, finally finished with Napoleon Bonaparte. But death was not the end for Napoleon, and it is not the end of this podcast’s involvement with the former emperor. Next time, we’ll continue today’s story with a second part examining how the actions of Napoleon’s final years, from the Hundred Days to his memoirs to his painful death, helped birth a new Napoleonic legend. Talleyrand may have been right that Napoleon’s death was not truly an “event,” but that’s only because it didn’t mark the end of the emperor’s impact on France.

Join me next time for The Siècle, Episode 21: The Afterlife of Napoleon.

-

Philip Dwyer, Napoleon: Passion, Death and Resurrection, 1815-1840 (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), 133. There are multiple versions of the quip reported, making it uncertain what, exactly, Talleyrand actually said. ↩

-

Andrew Roberts, Napoleon: A Life (New York: Viking Penguin, 2014), 774. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 774-5. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 775. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 777, Dwyer, Napoleon, 3-4. ↩

-

John Smart, “Napoleon on Board the Bellerophon at Torbay,” in Clement Shorter, Napoleon and his Fellow Travellers (London: Cassell and Company, Limited, 1908), 300. ↩

-

Dwyer, Napoleon, 13-4. Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 781. ↩

-

Wikipedia contributors, “Jamestown, Saint Helena,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia (accessed June 18, 2025). ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 782. Dwyer, Napoleon, 39-40. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 790. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914 (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 80-1. ↩

-

Sudhir Hazareesingh, The Legend of Napoleon (London: Granta Books, 2004), 17. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 789. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 792-3. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 17, 796. Caroline Bonaparte died at 57 and Pauline Bonaparte at 44; Napoleon’s son Charles Léon died of the disease at the ripe age of 81. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 796-7. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, 798-801. ↩