Episode 24: Lafayette in America

This is The Siècle, Episode 24: Lafayette in America.

Welcome back, everyone. Last time, we followed the unsuccessful Carbonari conspiracies in France in 1821 and 1822, which saw a range of conspirators including the old revolutionary hero, the Marquis de Lafayette, try and fail to overthrow King Louis XVIII. The episode ended with a defeated and nearly broke Lafayette boarding a ship to return to the country where he first achieved revolutionary fame: the United States of America.

Today, we’re going to leave Louis and instead follow Lafayette across the Atlantic. It’s a bit of a detour from our core story, but it’s an interesting one, and relevant for a major figure who has not yet finished his time in the spotlight back home in France.

To learn more about Lafayette’s so-called “Farewell Tour,” I spoke with Lafayette expert Alan Hoffman. Do note that our interview, conducted remotely over Zoom, has a few audio artifacts, for which I apologize. As always, you can visit thesiecle.com/episode24 to read a full transcript of this interview, along with images, annotations, and a link to buy the book Hoffman’s published about Lafayette’s voyage to America.

Now, on with the interview.

THE SIÈCLE: My guest today is Alan Hoffman. Alan Hoffman is the President of the Massachusetts Lafayette Society and the American Friends of Lafayette. He is the translator of Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825, which is the journal kept by Auguste Levasseur, who was Lafayette’s private secretary during his 1824 American tour. He has also lectured widely on Lafayette. Alan Hoffman, welcome to the show!

ALAN HOFFMAN: Thank you for having me.

SIÈCLE: Why don’t we start off by talking a little bit about how you got interested in Lafayette?

HOFFMAN: Well, I was always interested in early American history. I was a history major at Yale and studied under Edmond Morgan, who was a great early American historian. In 2002, I read a book called America’s Jubilee: How in 1826 a Generation Remembered 50 Years of Independence by Andrew Bernstein. The whole first chapter was about Lafayette’s Farewell Tour, which I had no knowledge of at the time. And it kind of intrigued me so I started getting interested in Lafayette. I was in New York taking depositions – I was a practicing lawyer staying with my brother in law. It was September 17, 2002 — I know because I have billing records. He asked me what I wanted for my birthday and he wound up getting me two books at The Strand Bookstore, one a biography by Unger and the other a catalogue with three great essays about the art of the Farewell Tour and at that point I was hooked.

HOFFMAN: Well, I was always interested in early American history. I was a history major at Yale and studied under Edmond Morgan, who was a great early American historian. In 2002, I read a book called America’s Jubilee: How in 1826 a Generation Remembered 50 Years of Independence by Andrew Bernstein. The whole first chapter was about Lafayette’s Farewell Tour, which I had no knowledge of at the time. And it kind of intrigued me so I started getting interested in Lafayette. I was in New York taking depositions – I was a practicing lawyer staying with my brother in law. It was September 17, 2002 — I know because I have billing records. He asked me what I wanted for my birthday and he wound up getting me two books at The Strand Bookstore, one a biography by Unger and the other a catalogue with three great essays about the art of the Farewell Tour and at that point I was hooked.

Right: Samuel Morse, “Portrait of La Fayette,” 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

SIÈCLE: So, what is it about Lafayette in particular, and the Farewell Tour in particular, that really appeals to you?

HOFFMAN: Well what appeals to me about Lafayette is that he was kind of on the right side of almost all issues that we could explore during his lifetime. He of course was prominent in the American Revolution. He tried to export American doctrines to Europe and to South America. He supported national revolutions as vehicles for the rights of man. He was a human rights crusader. He was a lifelong — at least since he was 23 or 24 years old — abolitionist, an early abolitionist. He supported Protestant rights in France, Jews in France. He was against the death penalty. He was against solitary confinement. He supported Polish refugees during the Polish Revolution in France. He was supportive of prominent women as well. So it’s kind of like the complete package. He’s someone that I at least would love to have as a neighbor in 2020.

As for the farewell tour, I believe that the Farewell Tour was a unique event in our history, and perhaps in the history of the world. Now you may think that is Trumpian hyperbole, but I’m not the only person to say that. Hezekiah Niles wrote in Niles’ Weekly Register on November 6th, 1824 “The volumes of history furnish no parallel — no one like La Fayette has ever re-appeared in any country.”

In 1930 Edward Everett wrote a review of Auguste Levasseur’s journal, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825. He wrote this in the North American Review. Everett had welcomed Lafayette to Harvard College in 1824 when he arrived at Boston and was also the principal speaker at Gettysburg 39 years later. His Gettysburg address was 60 times longer than Lincoln’s. In any event, in his review Everett lavished praise on the book, Lafayette, and the Farewell Tour. And about the latter, he wrote, “an event taken in all its parts unparalleled in the history of man.”

So, Lafayette came on the invitation of Congress and President James Monroe. He sailed from Le Havre, France, on a packet ship, an American merchant vessel called the Cadmus, in July of 1824. Although he had last visited America in 1784 after the Treaty of Paris formally ended the American Revolution which he had shared the glory of winning on the battlefield. This visit 40 years later produced a fervid outpouring of affection from the American people for the last surviving major general of their revolution. During his 13-month Farewell Tour, he visited all 25 states, where he was celebrated and honored on an almost daily basis. There were parades, festivals, banquets, speeches, balls, triumphal arches built in many cities to honor him; dedication of many public monuments including the Bunker Hill Monument in June of 1825 where he helped to lay the cornerstone; and meet and greets with the people, the common people, who came to pay their respects to him and touch the “nation’s guest,” as he was commonly called during his extended visit. I certainly haven’t found any parallel in my studies to Lafayette’s Farewell Tour.

Below: Lafayette dedicates the cornerstone of the Bunker Hill Monument in Boston, on June 17, 1825. Drawing by Marie d’Hervilly, lithograph by Pierre Langlumé. Public domain via Lafayette Digital Repository.

SIÈCLE: Alright, so let’s dive more into that Farewell Tour. Why don’t we set the stage to start with. Listeners of The Siècle are well aware of the events in France that contributed to Lafayette’s decision to leave France and go to the United States — the failure of the Carbonari uprisings and other attempts that Lafayette had been involved in to bring liberal reform to France. What were some of the other factors in Lafayette’s personal life, as well as in America, that contributed to Lafayette’s visit in 1824?

HOFFMAN: I think that the principal reason that he came was that he wanted to use this visit to improve the prospects of the liberals in France. As you so well documented in your last podcast, the liberals after the Carbonari conspiracy were on the outs, and in 1824 they lost that election and there were very few of them left in the Chamber of Deputies. So, it was an opportune time for Lafayette to leave. He didn’t have responsibilities in the Chamber of Deputies. He had been wanting to travel to America for a long time. He had numerous friends, including pretty much all of our surviving Founding Fathers — Monroe, Madison, and in particular Jefferson, who was his closest American friend. He took this opportunity to come to America.

HOFFMAN: I think that the principal reason that he came was that he wanted to use this visit to improve the prospects of the liberals in France. As you so well documented in your last podcast, the liberals after the Carbonari conspiracy were on the outs, and in 1824 they lost that election and there were very few of them left in the Chamber of Deputies. So, it was an opportune time for Lafayette to leave. He didn’t have responsibilities in the Chamber of Deputies. He had been wanting to travel to America for a long time. He had numerous friends, including pretty much all of our surviving Founding Fathers — Monroe, Madison, and in particular Jefferson, who was his closest American friend. He took this opportunity to come to America.

Now, what did he find when he arrived in America? The Monroe era is called the “Era of Good Feelings,” and to a large extent it was, but there were a number of challenges and crises that occurred in the five years preceding his visit. There was the Panic of 1819, which created a depression with the collapse of the land and commodities markets. There was of course the crisis over the admission of Missouri and the question of expansion of slavery into the territories. And it was solved temporarily by the Missouri Compromise, but the sectional conflict was always inherent in America prior to the Civil War. Then, there was the contested election of 1824, which had actually five candidates – John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, Crawford and Calhoun and of course Jackson. The election kind of came to an ultimate conclusion in November of 1824 which left Jackson ahead in both the popular votes and Electoral College votes, but without a majority, and it went into the House of Representatives. It was a very controversial time.

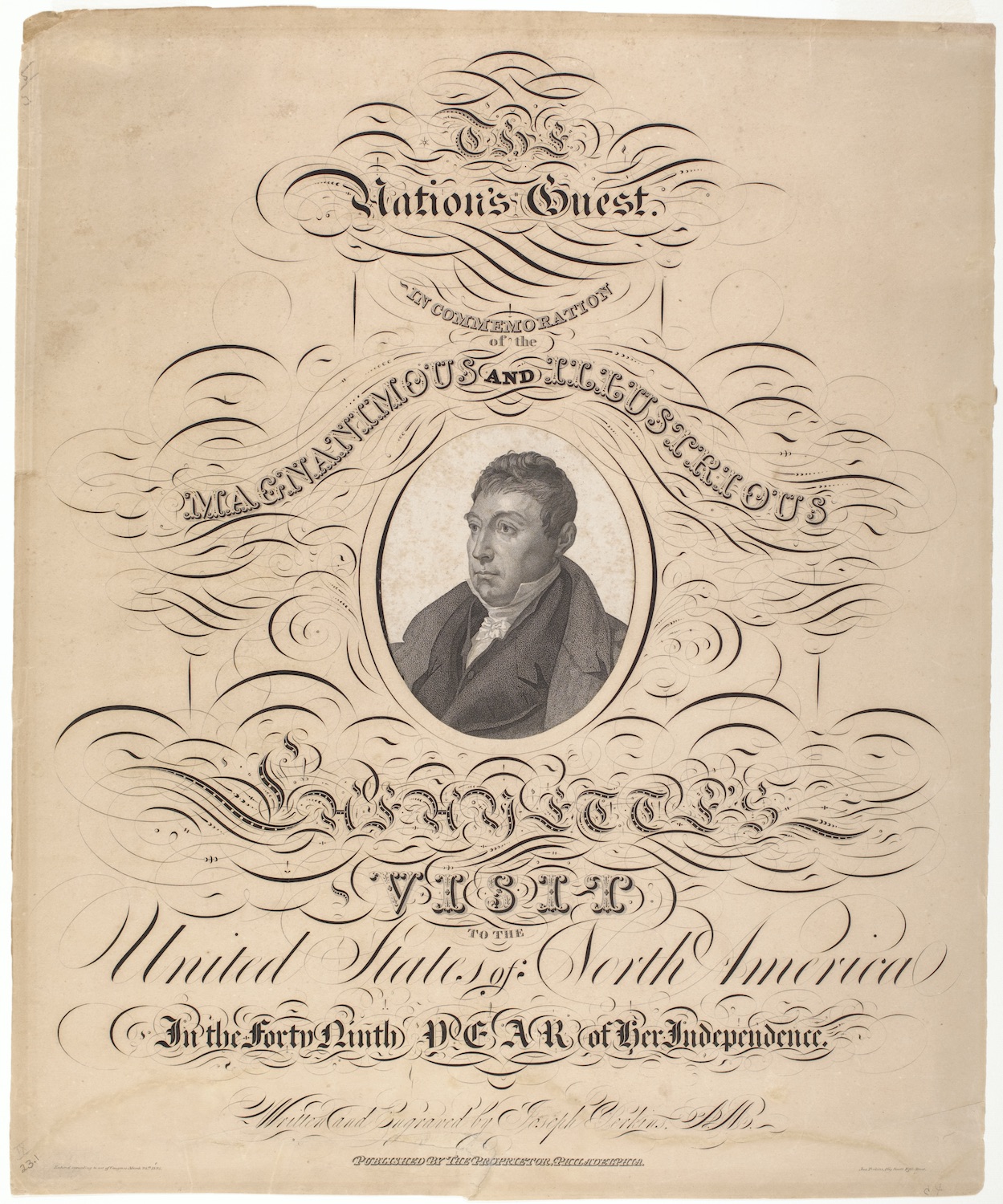

Above: Joseph Perkins, “In commemoration of the magnanimous and illustrious Lafayette’s visit to the United States of North America in the forty ninth year of her independence,” March 28, 1825. Public domain via Lafayette Digital Repository

So that’s what Lafayette faced when he arrived. What happened when he arrived was that his presence seemed to ameliorate all of these stresses on America. People came together to honor Lafayette. Wherever he went there were events. During the tour, Lafayette and his welcoming speakers constantly reminded each other of the success of the American experiment and that that success was a direct result of the military and political actions of the founding generation which Lafayette embodied. There were repeated references to the growth of the population and the success that the liberated colonies had achieved in manufacturing, agriculture, commerce, the arts and sciences, as well as the spread of public education. It was thought that the republican institutions that the [American] Revolution had ushered were the single most important cause of the great progress that was made. There was also an intense feeling of gratitude to the military and political leaders that won the republic as they were on the cusp of the Jubilee year of 1826. Now Lafayette was the embodiment of this founding generation — a blast from the past. And his repeated affirmations that Americans had done well, that they should be proud of their accomplishments, ameliorated the anxieties created by the financial, sectional, and most recently political crises that were on hand.

SIÈCLE: And of course, Lafayette wasn’t traveling alone: he had a secretary with him, Auguste Levasseur, who wrote the book you translated. Tell us about Levasseur.

HOFFMAN: Well Lafayette’s party was a party of four — himself; a valet called Sebastian Wagner, who is referenced only once in the entire book, and they called him Bastian; and his son Georges Washington Lafayette; and Auguste Levasseur.

Now, Levasseur was an interesting character. He had been a military officer in France. He served in the 29th Regiment stationed at Neuf-Brisach, which you mentioned in your podcast. In contemporary newspaper accounts during the Farewell Tour, he is sometimes referred to as Colonel Levasseur. In [1823] he had been involved in the Carbonari Conspiracy against the French monarchy, specifically in the Belfort plot. Now Thomas Jefferson adverts to this aspect of Levasseur’s early career in a letter that he wrote to Lafayette shortly before Lafayette visited Monticello in 1824, Jefferson writes, “And the revolutionary merit of Monsieur Levasseur has that passport to the esteem of every American and to me, the additional one of having been your friend and cooperator and he will, I hope, join you in making headquarters at Monticello.”

So the principal reason that Lafayette brought Levasseur in 1824 was to provide dispatches to liberal associates in France for publication in sympathetic newspapers and journals. These dispatches included speeches, addresses, and news articles. This was deemed necessary to fulfill what I consider to be the main purpose of the Farewell Tour — to revive the liberals’ political prospects in France by publicizing the lessons that the successful American experiment in republicanism could teach Europeans.

SIÈCLE: So why don’t we take sort of a bird’s eye view of the tour. Obviously, we could talk for hours about everything that Lafayette did. Where did he land and what was sort of the general course of the tour, in just a minute or two?

Above: Landing of Gen. Lafayette at Castle Garden, New York, 16th August 1824, artist unknown, 1886. Public domain from The New York Public Library

HOFFMAN: Well he landed in New York Harbor on Staten Island, because it was a Sunday and the city was not ready for its big celebration. On August 15, 1824, after spending some time in New York, he went to New England. There were events in Connecticut and Rhode Island. He spent over a week in Boston. He went up to New Hampshire, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; headed back to New York, and up the Hudson to Albany and Troy. Then he headed west to New Jersey, Philadelphia, down to Washington through Delaware and Maryland, down to Washington, D.C., where he spent the winter. But he made a number of side trips.

During that time his original intent was only to stay about four or five months and visit the original 13 states, but then he started getting invitations from the rest of the country, his son George, with the postmaster general and others, plotting out the rest of his trip. It was a southern and western swing through the South, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, with stops along the way in Mississippi and other places. Then he went to Illinois, and then he ultimately headed back east, because he had promised to attend the Bunker Hill Monument celebration on June 17,1825, and he headed east. He was one of the earliest travelers on the Erie Canal. He went to Albany on the Erie Canal and then he headed south again, and he wound up further east to Boston to the Bunker Hill Monument celebration, spent some time there. He went to New Hampshire again, this time went to Concord, the capital, and headed west; got to Vermont, his 24th state, and he headed back to New York for July 4. On July 14 he headed to Philadelphia and ultimately wound up in Washington, D.C., where he lived with John Quincy Adams in the White House until he left in early September. So those were kind of the outlines of the Tour.

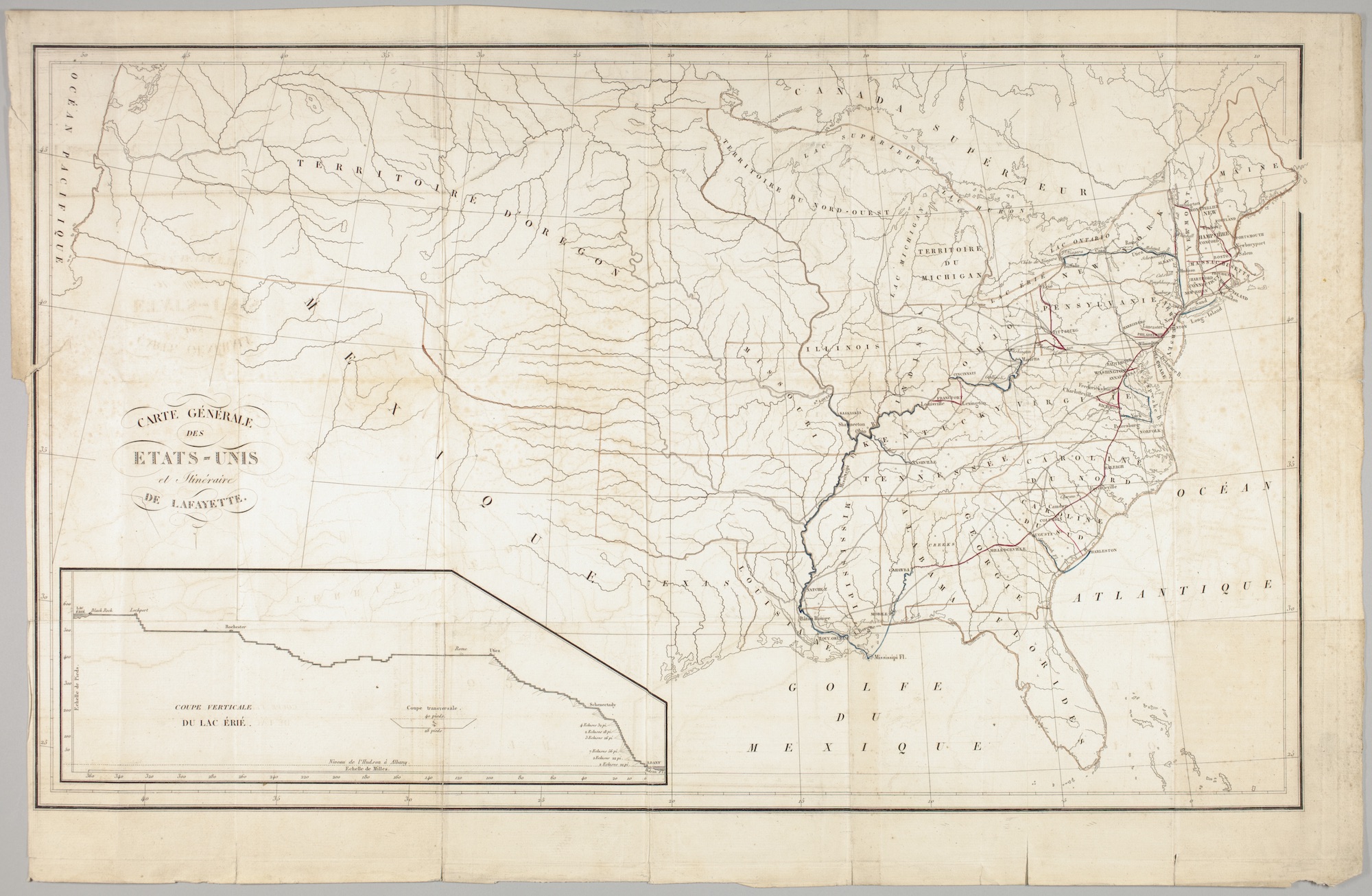

Above: General map of the United States and the itinerary of Lafayette. The red line represents the land route, and the blue line the water route. Unknown artist, Paris, 1829. Public domain via Lafayette Digital Repository.

SIÈCLE: You talked about his trip through the South, and obviously slavery was still a major component of Southern life and would be for decades to come. You’d mentioned the sectional tensions that were already intense at that point. And of course, Lafayette had long connections to abolitionist movements.

HOFFMAN: That’s right.

SIÈCLE: Was slavery an issue during his visit to the parts of America where slavery was practiced then?

HOFFMAN: Yes, it was. Lafayette believed that being the nation’s guest, as he was, that he couldn’t be as frank as he was, for example, with Thomas Jefferson in their correspondence about the evils of slavery. But he took symbolic steps pretty much wherever he went. In New York City, for example, he visited the African Free School and a young boy — an 11-year-old boy by the name of James McCune Smith — thanked him for all of his work against slavery. That young boy was not able to go to medical school in America. He went to Scotland and became a doctor. He became a leading abolitionist and he was an associate of Frederick Douglas.

When he went south, many of the local leaders of municipalities forbade slaves and freed Black men from attending his events because of Lafayette’s abolitionist reputation. But he found a way to make his point known. At Yorktown, according to a newspaper account, he embraced a double agent for him during the American Revolution — a slave at that time whose name was James Armistead — who became James Lafayette after Lafayette wrote a memorial for him, and the Virginia Legislature gave him his freedom and paid his owner 100 pounds. In Columbia, South Carolina, a former slave by the name of Pompey Dawson crashed a cocktail party after a public parade. He came to see Lafayette. He went by the militia who were guarding the entrance and Lafayette recognized him. He was the first servant, as Lafayette said, who waited on him when he came to America in 1777. They shook hands, Lafayette called for a drink of champagne with Pompey. They shared that drink together and then Pompey left. In Savannah he also greeted a slave at his headquarters. When he was in New Orleans, he made a point to shake the hands of every member of an African American militia who had fought in the war of 1812.

And then there’s the story of his visit to Lexington, Kentucky. A slave was on a fence when Lafayette’s carriage drove by and Lafayette tipped his cap to him! And the slave turned around and didn’t see anyone else on the fence and he ran away because he was afraid that people would be angry because Lafayette acknowledged him. That slave said in a memoir many years later that at that moment “that recognition from Lafayette convinced me that I had to escape and get out of this condition.” And he did. He came to Boston. His name was Lewis Hayden — he was a leading abolitionist in Boston. So, Lafayette in his own way made an impact, although he did it in his own way.

SIÈCLE: You’ve mentioned a couple of times the various celebrations and parties and events that accompanied Lafayette’s visits. Can you maybe focus on one or two of those events that maybe highlight the manner in which Lafayette was celebrated and received?

HOFFMAN: Yeah. Let’s go with his arrival in Philadelphia September 28, 1824.

Above: T. Holt, “Lafayette enters the city of Philadelphia in 1824.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

He was always met by militia who always escorted him in. They provided three or four carriages. He was on one with a leading town father, whose name was Judge Peters, who was a contemporary of Lafayette and knew him during the Revolution. They passed by a parade of all of the different types of business. For example, there was a float of printers who actually had a printing press, and they printed an ode to Lafayette and they threw them to all the people who were passing by. All the different disciplines had their own floats, it was like the Macys’ Thanksgiving parade. They went through nine wooden arches, welcoming Lafayette — the last one in front of Independence Hall. Then he was ushered into Independence Hall and he was given a speech by the mayor of Philadelphia. I think I’d like to quote his, because it makes — quite short — some of the points that he made. He’s in Independence Hall, there’s a statue of his mentor George Washington, and he says, “Here, sir, within these sacred walls by a council of wise and devoted patriots and in a style worthy of the deed itself, was boldly declared the independence of these vast United States which, while in anticipating the independence — and I hope the republican independence of the whole American hemisphere — has begun for the civilized world the era of a new and of the only true social order founded on the unalienable rights of man, the practicality and advantages of which are every day admirably demonstrated by the happiness and prosperity of your populous city.” So that was one of the, I would say, one of the more elaborate events, but every town tried to approach that in their attentions to Lafayette.

SIÈCLE: How did Lafayette’s visits impact America? The United States was still a young country at this time, George Washington still in living memory. How did Lafayette’s visit as this celebrity and this tie-back to the Revolution? How did it shape or validate America’s self-image and conception of its revolutionary history?

SIÈCLE: How did Lafayette’s visits impact America? The United States was still a young country at this time, George Washington still in living memory. How did Lafayette’s visit as this celebrity and this tie-back to the Revolution? How did it shape or validate America’s self-image and conception of its revolutionary history?

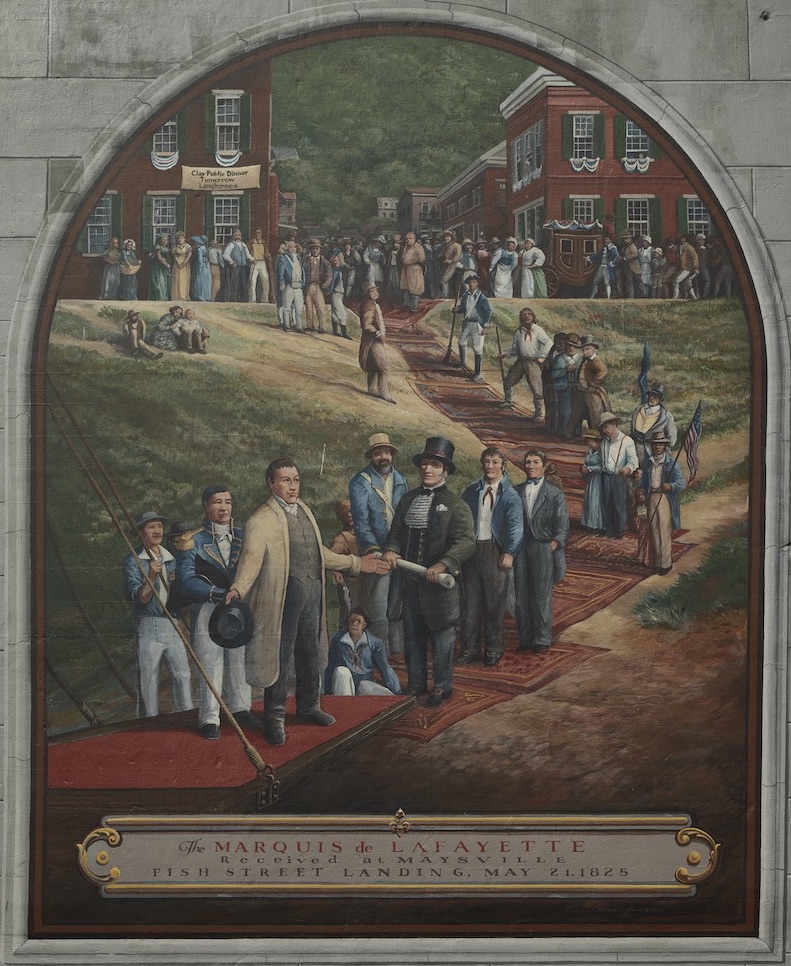

Left: A mural depicting the 1825 visit of the Marquis de Lafayette to Maysville, Kentucky, on May 21, 1825, by Robert Dalford and team. Public domain via Library of Congress.

HOFFMAN: I think it was a very important event for the morale of the American people and the American polity. As I mentioned before, he went around the country a vision from the past, one of the last founders, the last surviving major general of the American Revolution. He and his interlocutors validated the work that they had done and the present state of affairs of America. They did that in the speeches and the toasts that were made at all the banquets in many, many cities. I think during a time with some serious controversy, like the slavery issue and the territories in particular, also, the political campaign, it validated the success of the American experiment.

SIÈCLE: This was obviously a big deal at the time. You quoted some of these contemporaneous accounts. Did it leave a lasting legacy? Were these Lafayette events remembered long after Lafayette had gone back to France?

HOFFMAN: To some extent, yes. One of the effects at the time of the Farewell Tour there were only three cities, towns, townships, or counties named for Lafayette. One — the earliest city named for him — 1783 was Fayetteville, North Carolina. Two counties had been named for Lafayette in 1780: Fayette County in Kentucky, which is Lexington, it’s coterminous with Lexington, Kentucky and Fayette County, in Pennsylvania. As a result of the farewell, there are now 80 cities, towns, townships, and counties named for Lafayette. These names take six different forms — Lafayette, Lafayetteville, Fayette, Fayetteville, and then LaGrange and LaGrangeville. La Grange was his estate — his last remaining property. It actually came down in his wife’s family. Everyone knew that he lived in La Grange in 1824. For example, at the big event in New York, the Castle Garden Ball — which was a fantastic event — they had a transparency of his home, La Grange. There are thousands if not tens of thousands of streets, parks, avenues. There are 20 or so statutes of Lafayette in this country. There’s a mountain in my state of New Hampshire — Mount Lafayette they call it — it was named in 1824. Then there’s a river in Virginia, the Lafayette River, and there’s a lake in Florida, Lake Lafayette. So his name is out there. [For] many of these local and smaller towns, his visit was a big deal and it is still an important event for the local historical societies.

Above: Lauren Deroy and Alvan Fisher, “An eastern view of La Grange, the home of Marquis de Lafayette,” 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: French frigate ‘‘L’Hermione’’ in combat (action of 21 July 1781) by Auguste Louis de Rossel de Cercy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And then Lafayette’s reputation got two boosts, really three boosts, in the last ten years. One was the arrival of the Hermione, the reconstructed ship that came from France in 2015 and went up the coast. It was a model of the one that brought Lafayette back to America in 1780 after he had gone to France on furlough with the news at the French army and a fleet was coming.

And then Lafayette’s reputation got two boosts, really three boosts, in the last ten years. One was the arrival of the Hermione, the reconstructed ship that came from France in 2015 and went up the coast. It was a model of the one that brought Lafayette back to America in 1780 after he had gone to France on furlough with the news at the French army and a fleet was coming.

In the play Hamilton, Lafayette is an important character in it, and that’s got a lot of attention to Lafayette. Finally, there’s a young man by the name of Julien Icher, who came from France originally. He was an intern with the consul-general in the Boston area. With the help of my organization, The American Friends of Lafayette, he created a website following the footsteps of Lafayette’s Farewell Tour, and he returned and he’s now working to place markers. He has a sponsor, the Pomeroy Foundation, on the stops that Lafayette made in many of these cities. I’m going to a marker dedication in New Hampshire at Claremont on Dec. 28, for example.

SIÈCLE: Before his tour, obviously Lafayette was a famous person, but how famous was he in the United States? Did everybody know who Marquis de Lafayette was before his visit or was it to some degree his fame made by this visit?

HOFFMAN: I would say that he was famous at the time, but that fame was certainly enhanced by the Farewell Tour. There’s a little anecdote in the book when they are walking back from the Bunker Hill dedication. Levasseur reports that he’s overhearing the conversations and these young boys are talking about Lafayette’s role in the American Revolution. So, his role was known because he did keep in touch with America thru his correspondence, with Jefferson in particular, and other American leaders. Let’s say it exponentially advanced or enhanced through the Farewell Tour.

SIÈCLE: So we’ve talked about the impact of Lafayette’s Farewell Tour on America, what was the impact of the Tour on Lafayette? He had obviously come in the aftermath of some political failure in France. It seemed like the triumph of ultra-royalism there. How was Lafayette himself impacted by his tour and his reception?

HOFFMAN: My interpretation is that it empowered him. 1821 to 1824 was kind of a low point for him. He was restored of course he was restored economically as well, but he was restored in other ways. When he returned to France he ran again for the Chamber of Deputies. He was elected in 1827, and a number of other liberals were elected, and their bloc was enhanced certainly from what it was in 1824. His goal was always to have American doctrines adopted — that’s how he called them, American doctrines — adopted by France. Pursuant to that goal, in 1829 he went on another tour, this time in France. He visited a number of cities between Paris and his ancestral chateau, which he also visited at Chavaniac in the Auvergne. There were a number of stops in cities and the events mirrored the Farewell Tour. In one city there was a triumphal arch. The major stop was in Lyons, there were perhaps 60,000 people who came. There was a banquet and all of the speeches and the toasts were reported in the newspapers. There was one newspaper called L’ami de la Charte in Southern France, which reported all the events and then they were repeated in Parisian newspapers. Levasseur’s book came out in 1829. Lafayette believed Levasseur’s book would be influential in France by showing the success of the American experiment and how well Lafayette was treated. I believe that the tour empowered him to reengage in a serious way with politics in France.

SIÈCLE: You’d mentioned one of Levasseur’s purposes was sending all these dispatches back to liberal newspapers in France and correspondence and such. Is there any sense as to the effect that these dispatches had at the time?

HOFFMAN: That’s pretty hard to establish, but I can tell you one thing, the French ministry was not pleased. When Lafayette returned in early October of 1825, he traveled by land. He was heading back to Paris and ultimately to La Grange, but he traveled by land and he stopped at Rouen. At Rouen his admirers gathered — they had a band, etc., to greet him. He stayed overnight in the local gendermerie, and the army broke up the demonstration and injured a bunch of people. So, they were not happy with the effect of the Farewell Tour as reported by Levasseur and published in the French newspapers at that time.

SIÈCLE: Any closing thoughts that you wanted to share about Lafayette’s trip to America and the impact that it had?

HOFFMAN: Well, I guess I’ve said a lot, but my closing thought is that as I said it was an extremely important event in particular for America at a difficult time when several issues were troubling. Lafayette’s presence was like a balm over that period of time. Of course, as soon as he left, the Americans went back to the controversies that his visit had ameliorated. My final thought is that, as I also said before, I consider him to be one of the greatest human beings in the history of the world. And I would hope that other people study him and I’m pretty confident that you will reach the same conclusion.

SIÈCLE: Alright well, Alan Hoffman, thank you very much for coming on the show. He is the translator of Lafayette in America, which you can find a link to purchase at thesiecle.com/episode24. You can also visit lafayetteinamerica.com for more information. Mr. Hoffman, thank you for coming on the show.

HOFFMAN: Well my pleasure and thank you for having me.

My thanks also to all of you for following the show, and especially to listeners Zachary Wefel and Jarrod Routh, who bought me some French history books from my Amazon wish list that will be extremely useful for researching future episodes. This episode also received assistance from Jennifer Fuller, who transcribed the interview for me.

As a final addendum, you might have caught a reference in our discussion to Lafayette being “restored economically.” We didn’t get into that, but in addition to hosting parties for Lafayette across the country, Americans also showered him with gifts — and that included the U.S. government. Congress voted to give Lafayette $200,000 — that’s at least $5 million in modern terms — “in recognition of his services to the country and his personal financial losses in the cause of liberty in two worlds.” They also settled some legal disputes involving lands he’d been given in Louisiana. Both these actions helped the nearly bankrupt Lafayette get back on his feet. Lafayette pronounced himself opposed on principal to the gift, but the nearly bankrupt general accepted it anyway.1

He would return to France in 1825, coming back from his voyage looking “big, fat, rosy and happy,” as one friend put it.2 Much had changed during his year away, including one major new development that we’ll get to at last next episode.

Join me next time for The Siècle, Episode 25: The King is Dead.