Episode 29: The Doctrinaires

This is The Siècle, Episode 29: The Doctrinaires.

Welcome back, everyone! Be sure to check out the Battle Royale: French Monarchs podcast wherever you get your podcasts, or online at battleroyalepodcast.wordpress.com.

Before I begin, two quick notes. First, thank you again to all of you who’ve supported The Siècle, including not just the 81 of you who back the show on Patreon but also all of you who’ve told friends, family, and complete strangers about this show. It’s no exaggeration to say that word of mouth is the most important factor for independent podcasts like The Siècle. Second, I’m recording this episode while on the road, not in my usual home studio. So my apologies for any audio artifacts that creep in, from echos to conversations from the downstairs neighbors in my Airbnb. Alright, now, on with the show.

I’ve spent a fair amount of time over the prior 28 episodes talking about the political battles of the Bourbon Restoration. And when I’ve done so, I’ve usually described these fights in terms of “liberals” versus “ultra-royalists.” So back in Episode 23, about the Carbonari, I described how “France’s liberals were plotting military coups” while “ultra-royalists called for a national crackdown.”

But of course, this language has oversimplified some things. Not all royalists were Ultras. And not all liberals were out for revolution.

Today I’m here to shine the spotlight on one particular group of Restoration liberals, called the “Doctrinaires.” The Doctrinaires were a more moderate bunch than dashing figures we’ve spent time with so far like the Marquis de Lafayette. These relative moderates found themselves in the political center of the Restoration — liked being in the political center. But moderate doesn’t mean neutral. Depending on the ways the Restoration’s political winds were blowing, the Doctrinaires could be some of the Restoration’s most able supporters — or its most capable enemies.

A party on a sofa

Let’s start out with some basics.

One important thing to know about the Doctrinaires is that they were not numerous. This is not a political grouping like “liberals” or “ultra-royalists” that constituted thousands of general adherents. There were only a few Doctrinaires, a fact that left them the butt of jokes despite — or because — of their prominence.

For example, it was joked that the whole party could fit on a sofa. The British statesman Lord Acton admired the Doctrinaires, but still called them “leaders without followers.” One quip at the time joked of the Doctrinaires that, “They are four, but sometimes they boast of being only three, because it appears impossible to them that there can be four men of such force in the entire world; and sometimes they claim that they are five, but that is when they wish to frighten their enemies by their number.”1

Moreover, even with the small size, the identity of the “Doctrinaires” was not fixed — members came and went, and some were more closely identified with the group than others.

We can, however, say a few general things about the Doctrinaires before we meet them and learn about their specific ideas.

First, they were all liberals. That is to say, they tended to believe in individual rights more than group-based privileges; they embraced ideals like limited government, property rights, and division of powers.2

Second, they were all conservatives. That might seem odd from a modern American perspective, where “liberal” and “conservative” are opposites. But we’re using these terms in a more classical sense. As conservatives, the Doctrinaires were suspicious of radical change. They tended to accept the social order as it was — in need of some reforms, perhaps, but not dramatic upheavals.

In the context of the Restoration, in other words, the Doctrinaires were centrists. They generally believed in constitutional monarchy as structured by the Charter of 1814. As such they were fierce enemies of reactionary ultra-royalists who wanted to restore the ancien régime. But they were also none too fond of people seeking a new revolution, of overthrowing the king for a republic. The Doctrinaires said they wanted to find a so-called juste milieu, or “happy medium,” in between revolution and reaction.3

Finally, there’s the matter of the name. Why exactly were they “Doctrinaires”?

The name “Doctrinaire” was actually coined by an opponent as a pejorative, and somewhat reluctantly adopted after the fact by its members. This is actually pretty common back in this period — in Episode 9 I noted how the label “Ultra-royalist” was originally a pejorative, too. There are conflicting accounts of how the label “Doctrinaire” came about. Perhaps it was originally a reference to a religious school run by the so-called “Fathers of the Doctrine of Oratory” that one leading Doctrinaire had attended.4 One early printed reference was in the Bonapartist newspaper Le Nain Jaune from its 1816 exile in Brussels.5 The term was used in the French Chamber of Deputies in 1816 during a debate, in which an ultra-royalist deputy got annoyed by one speaker’s constant references to “principles” and “doctrines” and sarcastically declared, “Voilà, our ‘Doctrinaires’!”6

Historians generally agree that “Doctrinaire” is not exactly a fair label, insofar as it implies rigidity or a uniform belief system. As we’ll see, there were ideas that the Doctrinaires tended to agree on, but they had considerable differences, and as participants in practical politics they were often willing to compromise and bargain.7 But the Doctrinaires themselves eventually accepted the name, and so for lack of a better word we’re here today.

In any case, enough preliminaries. Let’s meet our Doctrinaires.

Royer-Collard

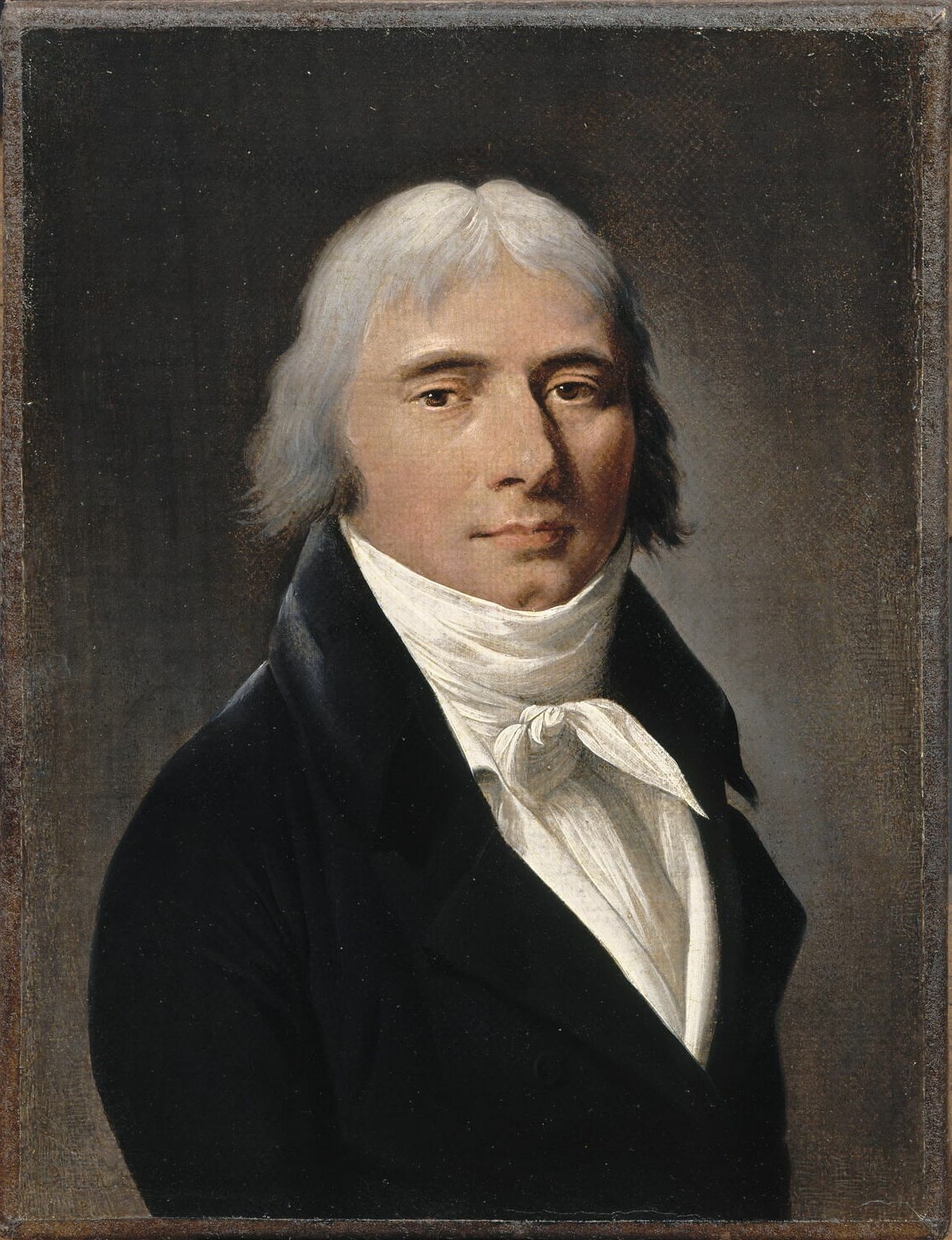

If anyone can be said to be the founding Doctrinaire, it’s a man named Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. A philosopher turned politician, Royer-Collard was born in 1763, and was 50 at the time of Louis XVIII’s first restoration in the spring of 1814. As a young man Royer-Collard had been active in the Revolution, and was aligned with the Girondin faction. This nearly got him executed when the Girondins were purged during the Reign of Terror, but he escaped, possibly due to protection from the Jacobin leader Georges Danton. Royer-Collard returned to elected office briefly under the Directory, a more moderate revolutionary regime, but his more interesting political involvement during the Revolution was behind the scenes.8

If anyone can be said to be the founding Doctrinaire, it’s a man named Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. A philosopher turned politician, Royer-Collard was born in 1763, and was 50 at the time of Louis XVIII’s first restoration in the spring of 1814. As a young man Royer-Collard had been active in the Revolution, and was aligned with the Girondin faction. This nearly got him executed when the Girondins were purged during the Reign of Terror, but he escaped, possibly due to protection from the Jacobin leader Georges Danton. Royer-Collard returned to elected office briefly under the Directory, a more moderate revolutionary regime, but his more interesting political involvement during the Revolution was behind the scenes.8

Left: Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard, 1819, by Louis-Léopold Boilly. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

At some point during the revolutionary chaos, Royer-Collard appears to have concluded that monarchy offered the best hope for good, stable government in France, and so he became a secret advisor to the exiled Comte de Provence — that is, the man we know as Louis XVIII. Royer-Collard wrote innocuous letters addressed to German businessmen, with secret messages for Louis in invisible ink updating the exiled king on events in France.9

Eventually his period as a spy faded away, and Royer-Collard devoted himself to philosophy. As a popular lecturer at the Sorbonne, he helped promote Scottish philosophy in France. But when Louis XVIII returned to power, the king rewarded his old adviser with an appointment in 1814 to oversee the press, and then in 1815 to a seat on the commission overseeing education in France, where he helped protect students and professors from government persecution for their political views.10 Also in 1815, Royer-Collard was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, where he would sit for the next 16 years.11

In the Chamber, Royer-Collard quickly became renowned for his speeches, which “possessed an unusual eloquence and elegant style” as well as deep philosophical grounding. A fellow Doctrinaire raved of Royer-Collard that, “As long as constitutional government will survive among us, his discourses will remain its definitive commentary.”12 And it wasn’t just his friends who were fans. As was common for the time, many of Royer-Collard’s speeches were printed and sold as pamphlets, and one of them is reported to have sold a jaw-dropping one million copies.13 This mass approval was matched among elites, who elected him to the prestigious Académie Française on the basis not of a groundbreaking book, but for his parliamentary oratory.14

Personally, our sources describe Royer-Collard as brilliant but indecisive, and sensitive to slights real or imagined. He was the original Doctrinaire, but sometimes reacted less than gracefully when his onetime disciples eclipsed him.15

Unfortunately for posterity, his famous speeches are the best view we have into Royer-Collard’s thought, because he never synthesized his beliefs into a book or other major work. His famous speeches were widely reprinted, but because these were always speeches about particular pieces of legislation, and thus grounded in specific political contexts, his ideas can appear inconsistent, adapting to meet the needs of the moment.16 His supporters, in contrast, have argued that beneath the surface-level inconsistency lies a clear liberal philosophy.17

Hercule de Serre

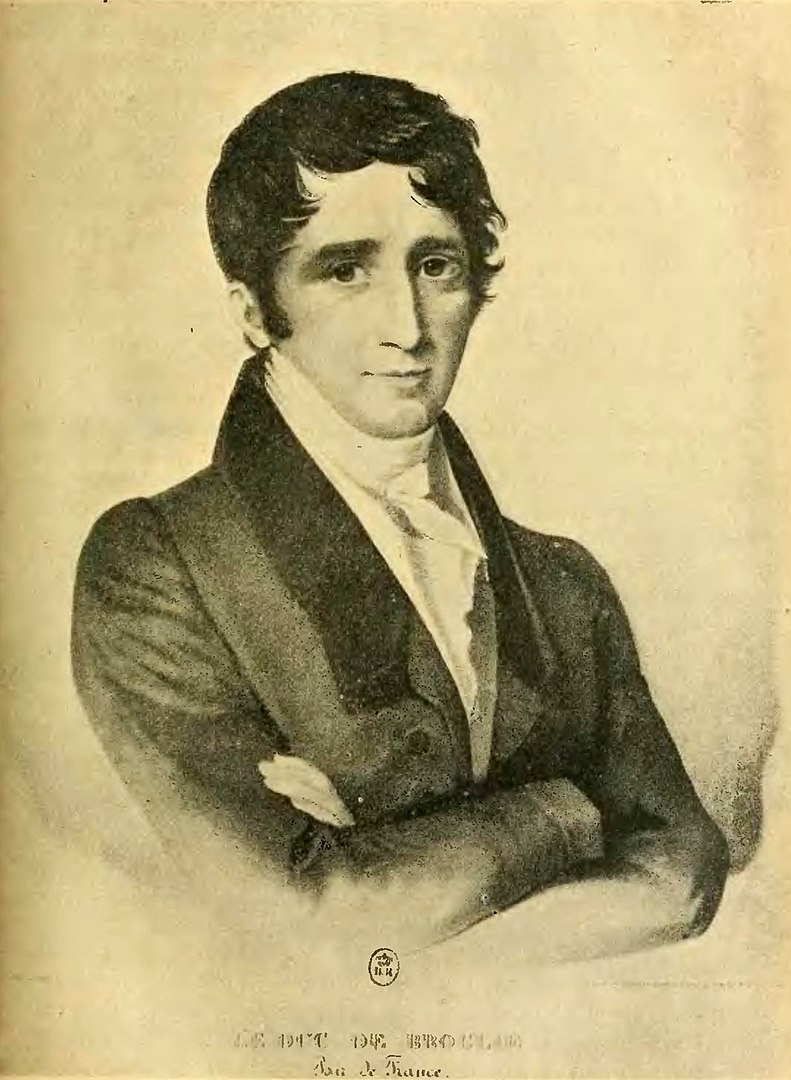

Somewhat more conservative than Royer-Collard was Hercule de Serre, born on March 12, 1776 to an aristocratic family. Unlike almost everyone else associated with the Doctrinaires, Serre emigrated abroad early on in the French Revolution, and fought in the émigré army assembled to try to suppress the Revolution. Serre, a lawyer, eventually returned to France and was appointed to several judicial positions by Napoleon, but supported the Restoration in 1814, when he was 38. Instead of retiring to private life during the Hundred Days, as Royer-Collard did, Serre went into exile with Louis in Belgium. But he turned against the ultra-royalists as a member of the chambre introuvable, and soon was drawn into Royer-Collard’s orbit.18

Somewhat more conservative than Royer-Collard was Hercule de Serre, born on March 12, 1776 to an aristocratic family. Unlike almost everyone else associated with the Doctrinaires, Serre emigrated abroad early on in the French Revolution, and fought in the émigré army assembled to try to suppress the Revolution. Serre, a lawyer, eventually returned to France and was appointed to several judicial positions by Napoleon, but supported the Restoration in 1814, when he was 38. Instead of retiring to private life during the Hundred Days, as Royer-Collard did, Serre went into exile with Louis in Belgium. But he turned against the ultra-royalists as a member of the chambre introuvable, and soon was drawn into Royer-Collard’s orbit.18

Right: Hercule de Serre, drawn circa 1842 from an earlier portrait by Mademoiselle de Monfort. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1817, Serre was elected as president of the Chamber of Deputies, an office he would hold for two years until resigning to become minister of justice under Élie Decazes. In that role he worked with the other Doctrinaires to lift press censorship.19 But when Decazes turned to the right in late 1819, Serre supported him — creating a split with the other Doctrinaires like Royer-Collard, who went into opposition.20 Serre remained in the new Richelieu government and defended the Law of the Double Vote in 1820. But Serre, in line with his past opposition to the Ultras, refused to join Joseph Villèle’s new Ultra ministry in 1821.21 He remained in politics as a member of the center-right — in a period where most of the Doctrinaires were center-left — until his untimely death in 1824, aged just 48, from a lingering illness.22

Victor de Broglie

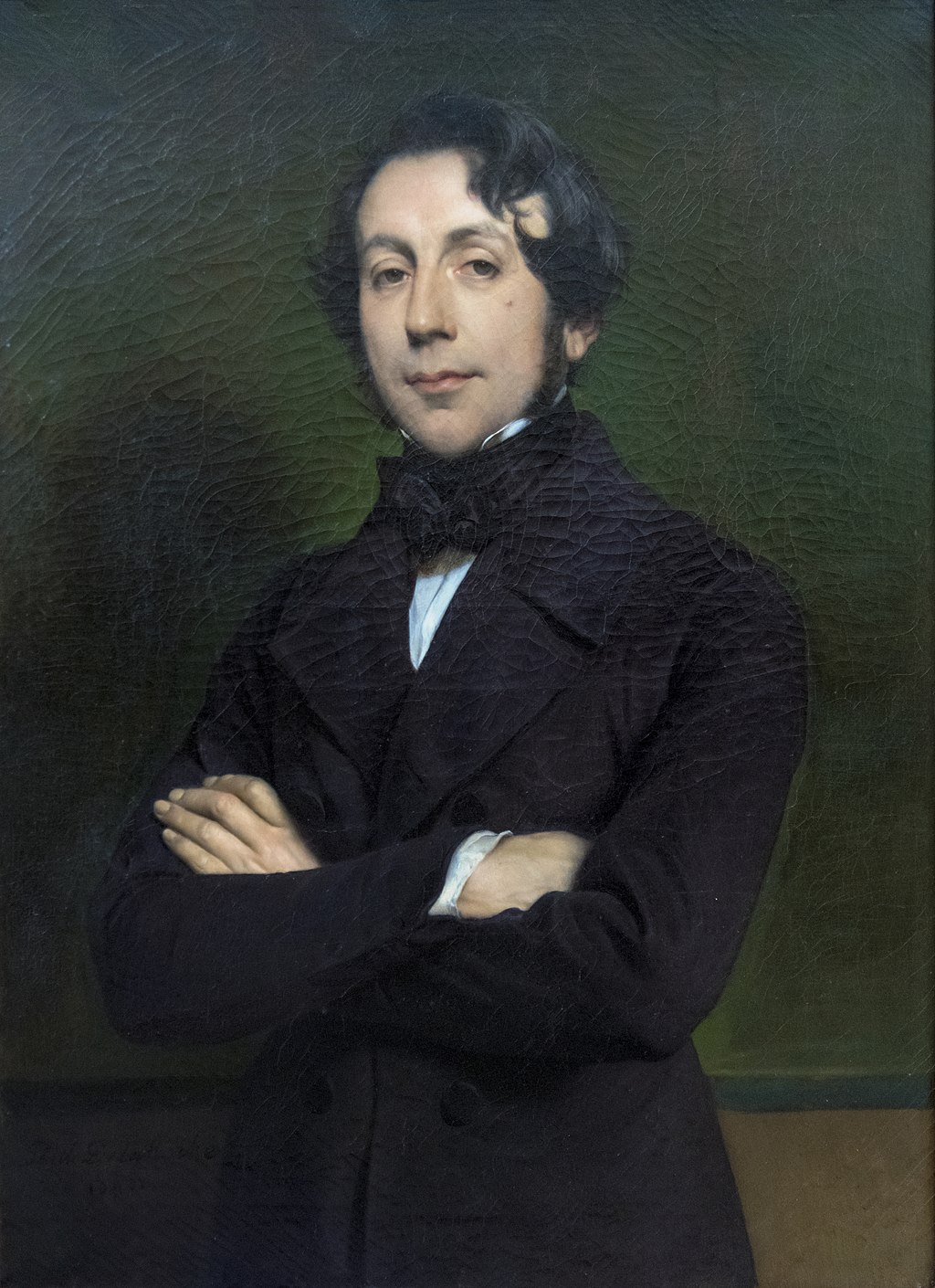

Perhaps the most illustrious ancestry of any of the Doctrinaires was that of Victor de Broglie, who was born on Nov. 28, 1785. He was the heir to the ancien régime House of Broglie, and became the third Duc de Broglie in 1804 at the age of 18. Victor’s grandfather was a proud émigré; his father, in contrast, was an enthusiastic revolutionary before falling victim to the Reign of Terror in 1794. As a young man Victor de Broglie was appointed to Napoleon’s Council of State, despite not being an enthusiastic Bonapartist. He even helped found Le Nain Jaune in 1814 under the First Restoration, at age 28.23

Perhaps the most illustrious ancestry of any of the Doctrinaires was that of Victor de Broglie, who was born on Nov. 28, 1785. He was the heir to the ancien régime House of Broglie, and became the third Duc de Broglie in 1804 at the age of 18. Victor’s grandfather was a proud émigré; his father, in contrast, was an enthusiastic revolutionary before falling victim to the Reign of Terror in 1794. As a young man Victor de Broglie was appointed to Napoleon’s Council of State, despite not being an enthusiastic Bonapartist. He even helped found Le Nain Jaune in 1814 under the First Restoration, at age 28.23

Left: Victor de Broglie, artist unknown, sometime between 1815 and 1848, possibly early 1830s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile in 1816 Broglie married into another illustrious family — though illustrious in a different way. Broglie married Albertine, the Baronness Staël von Holstein, who was the daughter of the famous author Madame de Staël. Madame de Staël in turn was the daughter of Jacques Necker, the Swiss banker who famously served as Louis XVI’s finance minister in the days leading up to the French Revolution.

You might note as well that I mentioned Albertine’s mother, but not her father. That’s because, while her official father was the Swedish diplomat Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, her actual father was probably the author, philosopher and politician Benjamin Constant, with whom Madame de Staël had a long affair.24

Albertine, the new duchesse de Broglie, was noted for being charming, frank, warm-hearted and independent-minded. She was also a devout Protestant, though she got along well with her Catholic husband. Albertine inherited her mother’s famous salon in 1817 when Madame de Staël died, and as such created the social center for the Doctrinaires. The gatherings there were noted for the quality of the conversation compared to other salons, though Albertine herself admitted that her guests lacked easy, aristocratic charm. “When one lives among Doctrinaires,” she said, “one is not displeased to relax from time to time in a very gentle politeness. They are self-indulgences to which one should not treat oneself for too long, for fear of weakening, but en passant they do one good.”25

Victor de Broglie’s political career in the Restoration started with a bang. Louis XVIII appointed him to the Chamber of Peers, and when Broglie finally turned 30 and assumed his full rights there, it was Nov. 28, 1815 — right in the middle of the treason trial there for Marshal Ney. Broglie was the only member of the entire Chamber who voted against convicting the Napoleonic general.26

Broglie was noted for his “high integrity and character,” for his “grave and powerful eloquence” in speeches, and for his attention to the nitty-gritty details of legislation — an attention to detail that bleeds through his enlightening but often pedantic memoirs.27

Prosper de Barante

Prosper de Barante was born on June 10, 1782, and was 31 at the start of the Restoration. Politically, he worked in a variety of administrative roles, including as a prefect under the First Restoration and an official in the finance ministry in 1816. Like most other Doctrinaires, he lost his formal positions in 1820. But this worked out alright for Barante, who was already an established writer with a passion for history. Sent home, he threw himself into research, and a few years later published a 12-volume History of the Dukes of Burgundy that earned him widespread acclaim and immediate induction into the Académie Française.28

Prosper de Barante was born on June 10, 1782, and was 31 at the start of the Restoration. Politically, he worked in a variety of administrative roles, including as a prefect under the First Restoration and an official in the finance ministry in 1816. Like most other Doctrinaires, he lost his formal positions in 1820. But this worked out alright for Barante, who was already an established writer with a passion for history. Sent home, he threw himself into research, and a few years later published a 12-volume History of the Dukes of Burgundy that earned him widespread acclaim and immediate induction into the Académie Française.28

Left: Prosper de Barante, 1814, by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Barante over his life wrote some of the most complete and coherent works setting out Doctrinaire ideas, both on their own terms and against that of the Ultras. He was renowned for his “common sense and talent for conversation,” but later historians criticized his writing style as sometimes unclear, “prosaic and heavy.”29

Charles de Rémusat

The youngest of the primary Doctrinaires was Charles de Rémusat. Rémusat was born on March 13, 1797, to prominent parents: his father Auguste, from an old Provençal family, was Napoleon’s chamberlain and made a count in 1808; his mother, known as Madame de Rémusat, was a famous writer and salon hostess. Charles had just turned 17 years old at Louis’s first Restoration in April 1814.

The youngest of the primary Doctrinaires was Charles de Rémusat. Rémusat was born on March 13, 1797, to prominent parents: his father Auguste, from an old Provençal family, was Napoleon’s chamberlain and made a count in 1808; his mother, known as Madame de Rémusat, was a famous writer and salon hostess. Charles had just turned 17 years old at Louis’s first Restoration in April 1814.

Right: Charles de Rémusat, 1843, by Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As Rémusat rose to adulthood in the 1820s, he became known as a gifted writer whose work was published in numerous newspapers. Broglie called him the “princeps juventutis” or “first among the young,” and said Rémusat had “one of the most naturally gifted minds I have ever known.”30 He also had a reputation among his friends as something of an intellectual dilettante, who flitted from idea to idea, never settling down to develop a single great work. Royer-Collard called Rémusat “the first of the amateurs in everything.” Balzac was more scathing, saying Rémusat was “a serious little boy [who] makes efforts to appear grave.”31

François Guizot

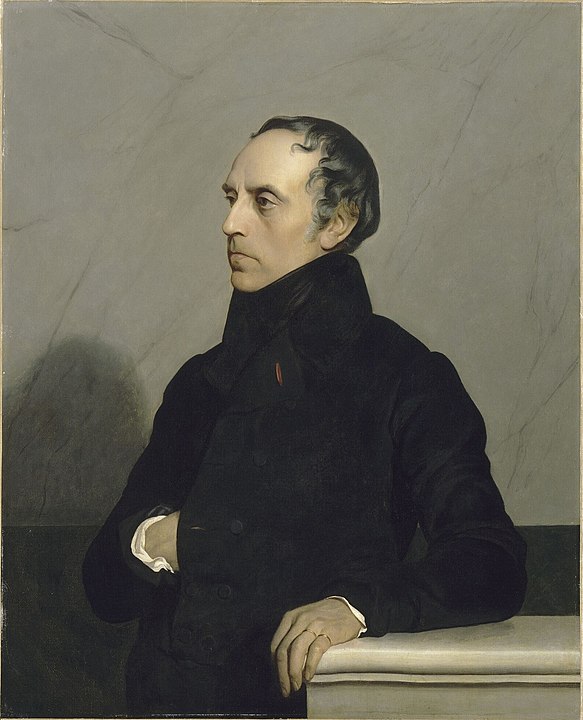

Last but absolutely not least is the man who would become the most famous of the Doctrinaires — and also the most infamous. François Guizot was born on Oct. 4, 1787, and was 26 years old at the time of the First Restoration.

Last but absolutely not least is the man who would become the most famous of the Doctrinaires — and also the most infamous. François Guizot was born on Oct. 4, 1787, and was 26 years old at the time of the First Restoration.

Right: François Guizot, circa 1837, by Jehan Georges Vibert after Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In those 26 years, Guizot had had a tumultuous childhood. He was born in Nîmes, the southern city noted for its violent conflicts between its Catholic and Protestant populations, from the Revolution through to the White Terror in 1815. The Guizots were Protestants, and serious ones; François’s grandfather had been a wandering pastor during a period where Protestant pastors were sometimes persecuted. His mother Sophie was a devout and dour Calvinist, believing that humans were created to suffer so that they might better know God.32

But it was Guizot’s father André who took the decisive action that shaped Guizot’s youth. André Guizot was an active revolutionary — no surprise given how dramatically the Revolution had improved the lives of French Protestants. But André was connected to the Federalist movement, provincial leaders who revolted against the Paris-based Jacobin government. Unfortunately for André Guizot, the Federalists were crushed, and André was eventually arrested and guillotined. François was six years old. The widowed Sophie Guizot, we’re told, lived with extreme frugality in order to raise and educate her two sons — first in Nîmes, then in Geneva, the Swiss Protestant city that had housed both John Calvin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.33

In 1805, the 18-year-old Guizot moved to Paris to study law. But like many law students before and since, Guizot quickly found himself frustrated. Though he had promised his mother that he’d pursue law, Guizot was instead seduced by Paris’s literary life. He took on work as a tutor, and the father of his students paid him not just in cash but in connections. One of these connections, an official with the Académie Française, hired him as a writer, and soon Guizot was publishing articles, books and translations. Eventually, even Madame Guizot agreed to let her son change careers.34

Pauline de Meulan

Another member of Guizot’s burgeoning intellectual circle was Pauline de Meulan, a woman born into a wealthy aristocratic family that had been ruined by the Revolution. After a fairly carefree childhood, Pauline turned to writing to make money for her family and discovered she had a talent for it. Soon she was publishing novels, criticism, works on education and moral improvement, and more.35 Her writing was piercing, original and witty.35 “Reason,” she quipped, “is unhappily only for reasonable people.”36

Another member of Guizot’s burgeoning intellectual circle was Pauline de Meulan, a woman born into a wealthy aristocratic family that had been ruined by the Revolution. After a fairly carefree childhood, Pauline turned to writing to make money for her family and discovered she had a talent for it. Soon she was publishing novels, criticism, works on education and moral improvement, and more.35 Her writing was piercing, original and witty.35 “Reason,” she quipped, “is unhappily only for reasonable people.”36

Left: Pauline de Meulan, 1802, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Pauline de Meulan acquired considerable renown, despite signing most of her works only with the letter “P.” She feuded with the distinguished Catholic polemicist Louis de Bonald; she attracted the praise of Madame de Staël and the literary critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, who included Pauline in his book, “Portraits of Celebrated Women” as “gifted, sagacious, exemplary and virtuous.”37

During her long career as a writer, Pauline often struggled with ill-health, which sometimes interfered with her ability to earn her living. This misfortune sets up one of the nerdiest meet-cutes imaginable. During one such period of illness, Pauline received an anonymous letter sympathizing with her plight and offering to ghostwrite articles for her until she was recovered enough to resume her own writing. This anonymous letter, you might have guessed, was written by François Guizot, just 19 years old. They had never met in person. But his anonymous offer was accepted. Soon the two met, and began collaborating openly, including founding and editing a journal together, called Annals of Education.38

Soon this friendship and intellectual collaboration turned to love — despite several significant obstacles. For one thing, Pauline de Meulan was nearly 14 years older than François Guizot, in her mid-30s while he was only around 20. They had highly contrasting personalities: he was an austere, over-serious Protestant; she was sociable, often satirical, and Catholic.39 But despite all these obstacles their affection was genuine, and in April 1812 the two were married. François was 24, and Pauline was 38.

The Man of Ghent

The year 1812 also saw another major milestone in Guizot’s life: one of his connections got him an appointment as an assistant professor of history, with a special exception from the normal age requirement for such a job.40 It was Guizot’s first-ever steady job. It also had one major side benefit: it brought the newly minted history professor in contact with the philosophy professor Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. The two men quickly became friends.41

Royer-Collard’s connections paid off for Guizot in 1814, when Napoleon abdicated and — as we’ve seen — Royer-Collard’s old pen-pal Louis XVIII rewarded him with government jobs. While he was at it, Royer-Collard arranged for Professor Guizot to be appointed secretary-general of the Ministry of the Interior. It was an unsung role, but one with huge potential for an energetic spirit like Guizot, who swiftly became the interior minister’s right-hand man and chief adviser. Before long Guizot was ghostwriting official reports that were presented to the king and read out in the Chamber of Deputies.42

In the spring of 1815 came Napoleon’s return for the Hundred Days. Louis XVIII and most of his officials fled into exile. Guizot returned to his university teaching job, but before too long he was sucked back into politics. With Napoleon failing to consolidate his regime, Royer-Collard and other moderate royalists began to anticipate that Louis would get a Second Restoration — and they began to worry that most of the people around Louis at his exile in Belgium were ultra-royalists like the king’s brother, the Comte d’Artois.43

As we saw in Episode 26, Artois was indeed increasingly influential on his brother during this exile in the Belgian city of Ghent. So to counter this influence, Royer-Collard dispatched an emissary to encourage Louis to stick to a moderate course — and that emissary was François Guizot. Guizot snuck out of France for a mostly futile visit to Louis’s exiled court. The reaction to this trip would be fairly typical for Guizot’s career: the ultra-royalists close to Louis at this time largely dismissed him, but the left for decades to come would attack Guizot as the “Man of Ghent” for his visit to the royalist court in the weeks leading up to Waterloo.44

Doctrinaires in power

Despite this, good things lay in store for the Doctrinaires. Instead of embracing ultra-royalism, Louis appointed a government led by Talleyrand. That was just the kind of thing Guizot had been sent to encourage, but Louis had agreed not because of the Doctrinaire arguments but because of pressure from the Duke of Wellington and other foreign leaders.45 And though Talleyrand didn’t last long, his successor Richelieu was no Ultra, either. Louis dissolved the chambre introuvable at the urging of people including Royer-Collard, and increasingly relied on his new favorite, Élie Decazes. And Decazes in turn relied on the Doctrinaires.

I did not list Élie Decazes as a Doctrinaire earlier, and he is generally not considered to be one. But Louis’s favorite was close to them, took their counsel, and let them take the lead drafting important pieces of legislation like the reorganization of the army, the electoral law of 1817, and the liberal press law of 1819.46

Historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny argues that Decazes viewed the Doctrinaires as merely “useful”: “they were just the ones to furnish him with high-sounding rhetorical reasons to dress up the political attitudes growing out of his tactical requirements.”47 In 1819, Guizot confided his view to Albertine de Broglie that Decazes “did not like the opinions of the Doctrinaires, but that he was very fond of them personally.” Though Decazes and the Doctrinaires were at that time allies, Guizot was under no illusions: he said Decazes was devoted to Louis, not to liberty.48

The break came soon, as you might recall from Episode 14. First came the controversial election of the old revolutionary Abbé Grégoire to the Chamber of Deputies. The Doctrinaires tried unsuccessfully to expel Grégoire on a face-saving technicality, but the whole episode convinced Louis and Decazes that the left was becoming too strong. They turned sharply to the right, prompting most of the Doctrinaires to go into opposition. “With Decazes there is no salvation,” Royer-Collard said. As we’ve seen, Hercule de Serre stayed in government through Richelieu’s second ministry, but when Villèle’s Ultra ministry took power in 1821 even Serre resigned.49

Doctrinaires in the wilderness

The Doctinaires now found themselves in the political wilderness. They either resigned their government positions, or were fired. Royer-Collard, for example, was sacked from his job on the council overseeing public education — leading to an immediate crackdown on student activists — and gave speech after speech eloquently opposing Ultra bills like the Law of the Double Vote in 182050 and the Sacrilege Law in 1825.51 He retained his seat in the Chamber, but he was fighting an increasingly lonely rear-guard action against overwhelming Ultra majorities.52

Guizot went back to his university job. This had originally been something of a sinecure, but deprived of his government work, Guizot discovered he was actually really good at it. His lectures were popular — too popular, it turned out, especially when his topic was the provocative “History of Representative Government in Europe.” The Villèle government banned him from lecturing.53 With even more time on his hands, Guizot wrote other books, including histories of the English Civil War.54 Overall, being in the opposition was pushing Guizot’s politics somewhat to the left, and he began to cooperate with more radical figures like Lafayette.55

Pauline Guizot had stopped her own writing for a period after marrying Guizot, but after he was fired she took up her pen again. She published an acclaimed novel in 1821, then two collections of children’s stories, and other works on education and morals. At the same time, she was assisting her husband’s research and writing in ways we’re unfortunately left to assume.56

The Duc de Broglie was still a member of the Chamber of Peers, where he had a fair amount of influence. In 1820, when the Peers were serving as a court for some anti-government conspirators, Broglie persuaded them to exonerate the one conspirator who knew enough to reveal the role played by liberal politicians in the scheme.57 Chief among those conspiring politicians who Broglie protected was Marc-René de Voyer d’Argenson, who you might remember from Episode 23 about the Carbonari. In addition to his radical politics and personal wealth, Voyer d’Argenson had another quality worth noting here: in 1796 he had married Broglie’s widowed mother, and was the duke’s step-father. Voyer d’Argenson’s radicalism meshed poorly with Broglie’s more conservative views. But when Voyer d’Argenson was at risk of being arrested during the Carbonari crackdown in 1822, Broglie pulled strings to get his stepdad a passport for England and spirited him out of the country until the heat died down.58

Guizot also played a role in the Carbonari fallout. Though he certainly didn’t participate in the conspiracies, at the height of the reaction in 1822 he pushed out a pamphlet called, “On the Death Penalty for Political Crimes.” This argued that a regime founded on rule of law had no need to impose the ultimate penalty on rebels and conspirators, a push for clemency for the Carbonari.59

This was the lot of the Doctrinaires in opposition — some political journalism, some history-writing, and using what influence they had left to try to sway events. And that brings us more or less up to date with our narrative. But I’m going to skip ahead a little here to bring one thread to its sad conclusion.

Death and marriage

Pauline de Meulan had, as we’ve seen, often struggled with ill-health. This didn’t end when she married François Guizot and had a child, also named François, in 1819, when she was around 46 years old. But things took a sharp turn for the worse in 1826, when she began to show signs of tuberculosis. Writing until nearly the end, in the summer of 1827 she breathed her last with her husband seated nearby, reading her a famous sermon about the immortality of the soul.60

In two important ways, Pauline did live on after her death. One was through her writing; after her death François saw to the publication of a posthumous collection of Pauline’s essays, which included a lengthy introduction by Rémusat appraising her life and works.

The other had to do with François, who was not yet 40 when his wife died. This can seem a little strange to our modern ears, but as she was nearing her end, Pauline Guizot apparently began actively trying to find a suitable woman for her husband to remarry after she died. Her pick was one of her nieces, Élisa Dillon, who after Pauline had fallen ill had helped the Guizots out with both housework and François’s research. “Spirited, charming and highly intelligent,” Élisa was 23 when her aunt died.61 A year later, she and François would marry according to Pauline’s desires. Despite this unusual origin story, the pair appear to have loved each other sincerely.62

To be a Doctrinaire

I want to close by zooming back out from these mini-biographies to the big picture: why were the Doctrinaires important?

Part of that answer, of course, is that they are going to do important things in the future of our narrative. But even sticking to where we are now, the Doctrinaires were important because they were people who formulated and expressed ideas — ideas about government and society that many of their contemporaries found very persuasive.

So let’s look at these ideas. What kind of things did the Doctrinaires believe?

As a preface, let me note that this will be a very cursory summary. People have written entire books on the question of the Doctrinaires’ beliefs — and if you want to read one, I recommend Aurelian Craiutu’s Liberalism Under Siege: The Political Thought of the French Doctrinaires. His analysis drives much of what you’re about to hear.

According to the Doctrinaires themselves, to be a Doctrinaire was primarily about method. Rémusat said the word “Doctrinaire” suggested “more a quality of tone and spirit than a consistent set of political and philosophical principles.” Guizot was more specific, writing that a “true” Doctrinaire was “someone who always conducts himself according to a general idea on any particular matter, singles out the general principles underlying a specific policy proposal, and ends by proposing a certain course of action after having considered a large number of consequences likely to follow, and after having carefully examined the merits of other alternative solutions.”63 In other words, Doctrinaires were driven by ideas, but always grounded in the practical application of those ideas. Or at least, so they claimed.

In practice, that balance between first principles and practical realities could tilt one way or the other. In 1816, for example, Royer-Collard and Guizot argued strongly that Louis both could and should dissolve the ultra-royalist-dominated parliament, the so-called Chambre introuvable. A few years later, when the political circumstances were different, they argued for the rightful prerogatives of the legislature.64

Defenders of the Revolution

But perhaps that’s unfair to the Doctrinaires. There was a consistent belief driving their writings during the Restoration — it just wasn’t about the rights and powers of parliament. Instead, the Doctrinaires were consistently animated by a fervent opposition to the ultra-royalists. The Ultras, the Doctrinaires believed, were misguided counter-revolutionaries who would drag France back into chaos and backwardness if given half a chance.

In 1821, when the Ultras were politically ascendant, Guizot wrote: “We have overcome the ancien régime; we shall always overcome it; but we shall have to fight it for a long time yet.”65 That first victory was the French Revolution.

And yet, while the Doctrinaires applauded the Revolution’s victory over the ancien régime and sought to continue the fight, they had profoundly mixed feelings about the Revolution. The key for them was the difference between the early days of the French Revolution — the admirable “spirit of 1789” — and the repugnant Reign of Terror. If Doctrinaires feared those who would return to the days of Louis XVI, they also feared those who would — in their minds, at least — return to the days of Robespierre.

Here’s an important bit of context, though: while the Doctrinaires feared extremists on both the right and the left, during the Bourbon Restoration it was the right-wing extremists — the Ultras — who seemed like the bigger threat to actually implement their vision. So the Doctrinaires directed most of their fire to the right.

Those Ultras also condemned the Reign of Terror as a black mark on history. The difference was that the Ultras saw the Terror as the inevitable consequence of the Revolution undoing ancient social bonds; the Doctrinaires insisted that one could have the reforms of 1789 without the terror of 1793. Similarly, they opposed those voices on the left who argued that the Revolution was still unfinished — for the Doctrinaires, the Revolution had done good work but was now over. As Rémusat put it, the idea was “bringing the Revolution to an end by creating genuine representative government.”66

Apologetic royalists

So what was the best way to preserve this middle path between revolution and reaction? For the Doctrinaires, there was only one institution for the job: constitutional monarchy. That is to say, they wanted a traditional king, bound by constitutional limits and assisted in government by an elected parliament. France had seen what absolute monarchy looked like, and it had seen what a republic looked like; for the Doctrinaires, the middle way was representative government paired with a king. The model here was not the fledgling United States, but Great Britain.67

As Broglie reminisced, “as a matter of fact, we all accepted the Restoration, either on principle, or from inclination, or from reason.”68 Victor Hugo was somewhat pithier, in an aside tucked away in Les Misérables. The Doctrinaires, he wrote,

were royalists, in principle, but apologetically. Where the ultras proudly asserted their faith, the doctrinaires were a little ashamed of it… Their mistake, or their misfortune, was to put old heads on young shoulders… They answered destructive liberalism with conservative liberalism, sometimes with rare intelligence.69

Guizot, in a neat rhetorical trick, tried to steal the Ultra’s slogan out from under them. The ultra-royalists spoke of “legitimacy,” by which they meant traditional, duly inherited monarchy. Guizot turned that on its head, and argued that it was the constitutionalists like himself who were true defenders of legitimacy; the Ultras were not true “legitimists” but merely “counter-revolutionaries” whose desire to turn back the clock would lead to bloodshed.70

Limited government

Underpinning all this was a Doctrinaire commitment to limited government. They supported a representative government as a check on the power of the king — and a king as a check on the powers of a runaway legislature.

This commitment extended to the philosophical question of where political power — or “sovereignty” — originated. At the time there were two major competing theories: “Divine right sovereignty” held that kings held absolute sovereignty, while “popular sovereignty” rooted all power in the people as a whole.

The Doctrinaires rejected both of these, arguing that they were two sides of the same coin. Both vested ultimate authority in one or more people, and were, they argued, liable to be abused. As Guizot wrote:

We have heard the sovereignty of the people proclaimed on the ruins of the divine right of kings… There has been no revolution in the name of liberty that did not promote in the end the rights of a new tyranny.71

In place of this, the Doctrinaires tended to support a theory they called “sovereignty of reason.” I’ll spare you more on the intricacies of this philosophy, and just note that by placing the root of political power in reason instead of any particular people, the Doctrinaires effectively deny absolute sovereignty to anyone. “No one,” Guizot wrote, “has the right to impose a law because he wills it… [N]o one has a right to refuse submission to it because his will is opposed to it.”72

Limited suffrage

From their opposition to popular sovereignty, you might not be surprised to learn that the Doctrinaires weren’t fans of universal suffrage, either. Like many people across the political spectrum during the Restoration, they endorsed an electorate limited by property qualifications — as I discussed back in Episode 7.73

This opposition to universal suffrage grew in part from contemporary beliefs that only those who were educated and economically comfortable could be trusted to cast fair, dispassionate votes. Owning property gave people a stake in society, the argument went, and the destitute didn’t have the education or leisure to adequately ponder affairs of state. The poor were believed to be vulnerable to their passions, susceptible to demagogues. As Broglie put it bluntly:

A hundred and twenty thousand French citizens who are represented are worth more than two million individuals who alienate their rights without reflecting on what they actually do.74

This elitist theory of suffrage had some interesting wrinkles. Guizot would years later become infamous for responding to requests for the right to vote by telling the poor to “get rich” — a somewhat out-of-context quote that I’ll break down in due course many episodes down the road. Back as early as 1817, Guizot was making the same general argument that political rights should follow socioeconomic standing — as part of his defense of the Revolution. He wrote in 1817 that, “When those who were poor, obscure, ignorant and without influence, had become rich, respected, enlightened and powerful, then they needed to occupy in law the place which they occupied in reality.”75

In practice, the Doctrinaires consistently opposed schemes for indirect elections. In the Restoration, Ultras liked a two-stage system, where voters would elect delegates to an electoral college who would choose each department’s actual deputies. Doctrinaires fought against the Law of the Double Vote in 1820, arguing that a voter who paid 300 francs per year in taxes — the minimum — should have just as much say as a voter who paid 3,000 francs per year. Their principal opponents at the time were not advocates for universal suffrage, but Ultras who wanted the richest electors to have a bigger say.76

Democracy in action

Having said all that about the Doctrinaires’ resistance to popular sovereignty and universal suffrage, you might be surprised to hear that the Doctrinaires were actually big fans of democracy!

Of course, what they meant by “democracy” was different from how we use the term today, or from its traditional understanding as rule by a polity’s citizen body. When the Doctrinaires spoke admiringly of the spread of democracy in France, they meant something more like “equality of conditions” and “equality before the law,” not whether everyone had the right to vote.

Here’s an example that helped me understand what the Doctrinaires meant. Whereas today we might define “democracy” as the opposite of “tyranny,” in one of his famous parliamentary addresses, Royer-Collard defined democracy as the opposite of aristocracy.77 In contrast to the ancien régime world dominated by aristocratic privilege, even a conservative monarchy like the Bourbon Restoration, where the Charter guaranteed legal equality for all citizens, might be said to be “democratic” under this definition.

And indeed the Doctrinaires argued that their idea of democracy had arrived in the Restoration, that it was here to stay — and that the future was one of ever-increasing democracy.

For example, in 1820, Hercule de Serre proclaimed in a speech that, “In our country, democracy is full of energy; one can find it in industry, property, laws, memories, people, and things. The flow is in full spate and the dikes can hardly contain it.”78

Guizot would claim in the 1830s that France was the “greatest modern democratic society,” and meant it as a compliment — though he distinguished France’s monarchical democracy from the “radical democracies” like Switzerland or the United States.79

These thoughts on democracy as an inevitable social force might remind some of you of Alexis de Tocqueville’s seminal 1835 work, Democracy in America. This isn’t a coincidence. While Tocqueville went further than the Doctrinaires in his analysis and praise of democracy, he was powerfully influenced by the 1820s arguments of Royer-Collard, Guizot and other Doctrinaires.80

Now, everything I’ve talked about today might be striking some of you as a little bit abstract. Well, there’s a reason I picked now to finally bring the Doctrinaires out of the background. In future episodes, they’re going to be playing increasingly central roles in our narrative — not just as functionaries for Louis or speechmakers for the opposition, but as organizers behind a looming political fight with huge implications: the Election of 1827.

You’re going to have to wait just a little bit for that, though. Next month we’re going to talk about another climatic event from 1827, and another topic I’ve been holding in reserve for the right moment. Why right now? Well, once you join me on a trip to the war-torn Peloponnesian peninsula of the 1820s, I think you’ll agree with me about the striking modern-day relevance of Episode 30: Greek-ing Out.

-

Aurelian Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege: The Political Thought of the French Doctrinaires (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2003), 27. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 17. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 76. ↩

-

Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard, to be introduced shortly. ↩

-

Technically then known as Le Nain Jaune Réfugié. ↩

-

Douglas Johnson, Guizot: Aspects of French History, 1787–1874, Studies in Political History (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1963), 32-33. Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 26. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 26. ↩

-

Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., s.v. “Royer-Collard, Pierre Paul.”. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 94. ↩

-

David Skuy, Assassination, Politics and Miracles: France and the Royalist Reaction of 1820 (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 143. ↩

-

Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., s.v. “Royer-Collard, Pierre Paul.”. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 27. Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 144. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 293. ↩

-

Benjamin Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris: The Sound of Modern Life, Cambridge Studies in Opera (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 1. ↩

-

Elizabeth Parnham Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1929), 29. ↩

-

Skuy, Assassination, Politics and Miracles, 181. Hugh Brogan, Alexis de Tocqueville: A Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 615-6. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 158-9. ↩

-

Skuy, Assassination, Politics and Miracles, 118. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 164. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 170, 179. ↩

-

Dictionnaire des parlementaires français de 1789 à 1889 [Dictionary of French parliamentarians from 1789 to 1889], s.v. “Serre (Pierre-François-Hercule de),” ed. Adolphe Robert, Edgar Bourloton and Gaston Cougny (1891), 305-6. . ↩

-

Achille-Léon-Victor, duc de Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, 1785-1820, ed. and trans. Raphael Ledos de Beaufort, vol. 1 (London: Ward and Downey, 1887), 287-8. “I had witnessed the birth of that satirical sheet,” Broglie wrote years later. “I had often attended the evening meetings at which the articles were discussed and decided upon. I was not even quite a stranger to the editing of the paper, in so far that I permitted the jokes and the anecdotes which I used to relate in rather a malignant spirit, I confess, to be published in that paper.”. ↩

-

Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., s.v. “Constant de Rebecque, Henri Benjamin.” ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 137-8. ↩

-

Raphael Ledos de Beaufort, introduction to Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, xii-xiii. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 30-1. See also Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie. ↩

-

Craiutu 29-30, Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., s.v. “Barante, Amable Guillaume Prosper Brugiére, Baron de. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 30. ↩

-

Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, 390. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 29. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 10. ↩

-

Johnson, Guizot, 2-3. Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 10-11. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 12. ↩ ↩2

-

Sainte-Beuve, Portraits of Celebrated Women, 371. ↩

-

Sainte-Beuve, Portraits of Celebrated Women, 367, 360, 384. ↩

-

Sainte-Beuve, Portraits of Celebrated Women, 370-1. Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 13. ↩

-

Sainte-Beuve, Portraits of Celebrated Women, 371. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 13. ↩

-

Johnson, Guizot, 3. Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 14. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 15-8. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 20. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 20-21. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 20-21. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 34. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 145. ↩

-

Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, 444. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 164, 179. ↩

-

Skuy, Assassination, Politics and Miracles, 181. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 376. ↩

-

For more on the dire political situation Royer-Collard and other liberals faced, see Episode 15 and Episode 18. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 35. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 342. Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 51. ↩

-

Sylvia Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 1814-1824: Politics and Conspiracy in an Age of Reaction (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 185. ↩

-

Sainte-Beuve, Portraits of Celebrated Women, 373, 380. Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 45. ↩

-

Alan Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes: The French Carbonari Against the Bourbon Restoration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), 47-8. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 209-10. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 151. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 56. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 57. ↩

-

Laurent Theis, “Eliza Dillon,” tr. Maureen Phillips and Julie de Rouville, guizot.com, April 30, 2022. . ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 76. ↩

-

Brush, Guizot in the Early Years of the Orleanist Monarchy, 23-4, Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 202. ↩

-

François Guizot, Du gouvernement de la France depuis la Restauration, et du ministere actuel [Of French government since the Restoration, and of the present ministry] (Paris, 1821), in French Liberalism: 1789-1848, ed. William Simon (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1972), 108. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 79-80, emphasis added. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 91. ↩

-

Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, 397. ↩

-

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, translated by Norman Denny (London: Penguin Books, 1982), 534. ↩

-

Guizot, Du gouvernement de la France…, 109-10. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 130. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 132. ↩

-

What made the Doctrinaires stand out was not that they opposed universal suffrage during the Bourbon Restoration, when relatively few people supported the idea. It was that they would continue to oppose universal suffrage for decades to come, as universal suffrage gained popularity and salience. But those future developments are beyond the scope of this episode. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 227. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 232-4. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 106. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 106. ↩

-

Johnson, Guizot, 47, 49. The “greatest modern democracy society” quote is a paraphrase from Johnson. ↩

-

Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege, 108-10. ↩