Episode 30: Greek-ing Out

This is The Siècle, Episode 30: Greek-ing out.

Welcome back! You just heard an advertisement for the online Intelligent Speech conference, taking place just next weekend. I’ll be giving a talk there, about a French warship that in 1816 suffered an infamous shipwreck. If you don’t think you’ve heard of it, you’re wrong — because it inspired one of the most famous paintings in world history. Visit intelligentspeechconference.com to buy your ticket to hear countless great presentations, including my talk: “The Wreck of the Medusa.” Even better: you can use the coupon code “siecle” — that’s “s-i-e-c-l-e” — to save 10 percent off your ticket. I hope to see you there!

Today we’re going to take a step back to cover a major event that’s been taking place in the background all the way since Episode 18, more than two years ago. Starting then, I talked about the wave of revolutions that rocked Europe in the early 1820s: first liberal rebellions in Spain and Italy in 1820, followed by the Carbonari conspiracies in France. All these revolts were eventually crushed, often by outside armies enforcing Europe’s conservative order. We saw France hem and haw, trapped between the comparatively liberal Great Britain and the absolute monarchies of the Holy Alliance: Russia, Austria and Prussia. Eventually, France invaded Spain and restored King Ferdinand to power.

There was one big revolution taking place at this time that I didn’t get into, however. I’ve been saving it for now, because while it kicked off in 1821, it took much longer than the other revolts of that period to resolve. I’m talking about the Greek Revolution, or the Greek War of Independence.

What you’re about to hear draws primarily on two superb books: historian Mark Mazower’s new book, The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe, and William St. Clair’s still-classic 1972 study, That Greece Might Still Be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence. You can find links to purchase both books at thesiecle.com/episode30.

Okay, let’s start out with some basic background. This is going to take us away from France for a bit, but I promise you this all ties back to Restoration France by the end.

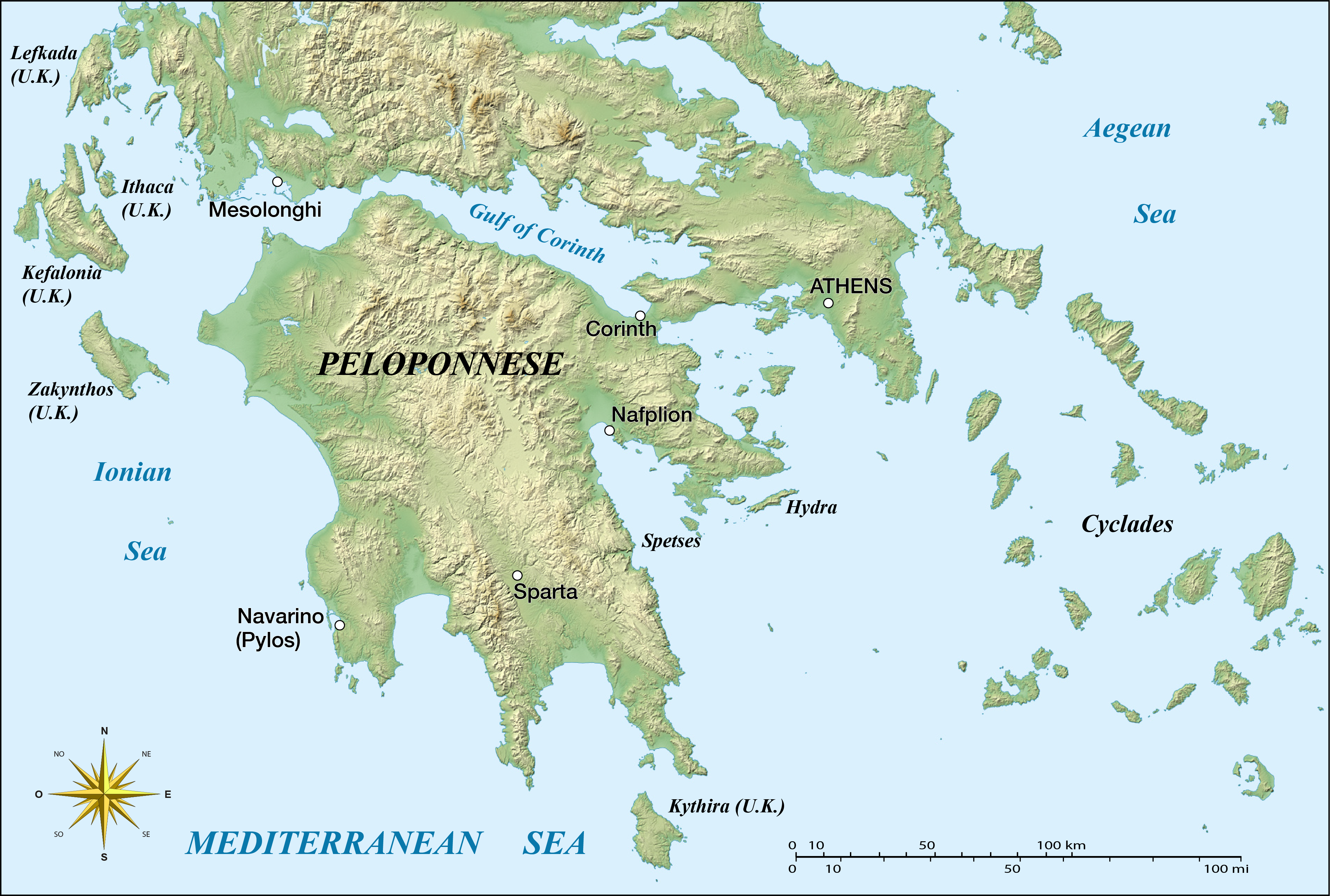

Key locations during the Greek War of Independence. Map by David H. Montgomery for The Siècle history podcast, based on original by Eric Gaba. Compass rose created by Wikimedia Commons user Serg!o. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution and Share-alike license, via Wikimedia Commons.

Meet the Greeks

As the Napoleonic Wars ended, the Ottoman Empire ruled — at least on paper – a vast stretch of territory including Egypt, Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, the Balkans, almost the entire North African coast, both the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coasts of Arabia, as well as Cyprus, Crete and thousands of other islands. It stretched from the edge of the Russian steppes to the Sahara Desert; it included Mecca and Medina, Carthage and Cairo, Algiers, Alexandria, Ankara and Athens — and, of course, its crown jewel, the great world city of Constantinople astride the Bosporus.

Demographically, there were perhaps 24 million people living in the Ottoman Empire at the time, though precise figures are hard to pin down.1 The Turks were the most powerful, but the empire included a host of other ethnic groups. The Ottoman armies invading Greece during this period will include Armenians, Egyptians, Bosnians, and fighters from even farther away, like Georgians, Zaporozhian Cossacks, and even some Greeks.

That designation, “Greek,” referred to one of the most prominent minority groups within the Ottoman Empire; it was a term part ethnic, part linguistic and part religious. Speaking Greek and affiliated with Orthodox Christianity, Greeks lived in significant numbers throughout the Ottoman Empire, not merely within the territory that today comprises the country of Greece — and this had been the case for millennia. There were sizable Greek populations in the Peloponnesian peninsula, in the Balkans, on islands throughout the Aegean, in Constantinople itself, along the west coast of Anatolia, and in Egypt — to just list a few of the major centers.2

Nominal borders of the Ottoman Empire circa 1817, before the eruption of the Greek War of Independence, overlaid on current national borders. Note that different parts of the empire had varying degrees of functional autonomy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hellenes and Romioi

I should probably talk a little more about that term, “Greek,” because the linguistic terminology here is important. First, “Greek” — or the French grec — is not the dominant term that Greeks themselves use to refer to themselves or their language. Today they tend to use the word “Hellene”; the official name of the modern country we call Greece is the “Hellenic Republic.”

Things were even more complicated 200 years ago. Many Greeks at the time didn’t call themselves Hellenes, either. That word was used exclusively to refer to the ancient Greeks. The most common term Greeks used for themselves was “Romioi” — an etymological reference to the Romans. In other words, the historical touchstone for Greek identity before 1821 wasn’t Athens or Sparta — it was the Eastern Roman Empire, what we today call the Byzantine Empire.3 The ancient Greeks were long dead, and pagans to boot. But Byzantine Constantinople had only fallen to the Ottomans a few centuries prior. The “Roman” identity was much more alive than the “Hellenic” identity was.

At least, that’s what the situation was for Greeks living in the Ottoman Empire. In western Europe, the situation was completely reversed. There schoolboys were raised on the Iliad and the Odyssey, on the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, on disputing philosophers on the streets of Athens. The Byzantines were either ignored or dismissed.4 Even the languages were different — the classical Greek taught in western schools was essentially a completely different language from the living Greek spoken in Greece itself. One illustrative example comes from the experience of an Englishman, fighting alongside the Greeks in 1825, who recited a stirring passage of Homer in classical Greek to his hosts. The response was a question from one of the Greek fighters: “What language is that?”5

This divide is not merely academic. From our current vantage point, we can see that the “Hellenic” identity largely won out as the basis for the independent Greek state. But that was hardly a foregone conclusion. Before the uprising began in 1821, Greeks who chafed under Ottoman rule weren’t pining for a nationalistic uprising. Instead, the dominant dream was for a concept called the romeïko, a quasi-mystical day of reckoning when Constantinople would be liberated due to some combination of God and men. It was to “make the romeïko” that drove many Greeks to take up arms in the first place.6 The ways in which this religious and imperial goal gave way to an ethnic and nationalist one is the story of the Greek Revolution — and, in some ways, the story of the 19th Century.

Hatching a plot

But now we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s step back to the Ottoman Empire in 1821. The empire’s Greek minority is in some ways economically and politically privileged.7 At the centers of power, many Greeks served in official positions for the Ottoman government. In rural areas with big Greek populations, local Greek landowners usually had a fairly free hand to keep order and collect taxes for the distant sultan.8 But this privilege didn’t prevent the spread of seditious ideas through elite Ottoman Greeks in the years after 1815.

The key ingredient that pushed simmering discontent over the top into open revolution wasn’t Orthodox Christianity, Byzantine dreams, or ethnic hatred. Instead it was something we’re much more familiar with here on The Siècle: western liberalism. These new ideas that have been roiling Western Europe for generations had also made inroads among educated, urban Greeks. And these elite Hellenes weren’t immune to the fervor for secret societies that I talked about back in Episode 23. In the west liberals organized in groups like the Carbonari. In eastern Europe, there was a new group called the Filiki Eteria, or Society of Friends — a secret society devoted to securing Greek independence.

I should interject here to note that I don’t speak Greek. I’m grateful to Poursa, the owner of the “Learning Greek” Discord server, for helping with my Greek pronunciations. Anything I got wrong is my fault, anything I got right is thanks to him.

The Eteria’s founders were largely from the prosperous Greek-speaking community in Constantinople, but it spread throughout the Ottoman Empire, into Western Europe, and — most crucially — into the Greek expatriate community in Russia.

The Eteria’s founders were largely from the prosperous Greek-speaking community in Constantinople, but it spread throughout the Ottoman Empire, into Western Europe, and — most crucially — into the Greek expatriate community in Russia.

Left: Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, by Thomas Lawrence, c. 1818-19. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Russia bordered the Ottoman Empire to the north, and had fought multiple wars against the Ottomans over the years as part of both territorial expansion and the Russian tsars’ claims to be the protector of their fellow Orthodox Christians. In the Tsar’s service were a number of Greek exiles holding prominent positions. That included Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, who served as Tsar Alexander’s foreign minister from 1816 to 1822. It also included a Russian cavalry officer named Alexandros Ypsilantis, who joined the Eteria and was appointed its leader after Kapodistrias refused.

The plan Ypsilantis and his fellow conspirators cooked up was for spontaneous uprisings of Greek populations across the Ottoman Empire, spearheaded by Ypsilantis himself at the head of an uprising in the Danubian Principalities — what today is parts of Moldova and Romania, and was then the military frontier between Russia and the Ottomans.9

Ypsilantis duly crossed the border on Feb. 21, 1821, and raised the standard of revolt in conjunction with some local Christian leaders. But this would be the high point for Ypsilantis — the Christian peasants in the Danubian Principalities never rose up en masse like Ypsilantis expected, perhaps not surprising since they were ethnic Romanians, not Greeks, and whatever resentments they had toward the Turks were matched by their grievances against the Greeks from Constantinople who the sultan had put in direct charge of the area. Ypsilantis’ own dithering weakened his military position further. Worst of all, though, Ypsilantis’s friend Tsar Alexander and his compatriot Kapodistrias categorically refused to support the Greek uprising with Russian armies. In an official letter to Ypsilantis, Kapodistrias wrote: “Russia is at peace with the Ottoman state… No help, either direct or indirect, will be accorded to you by the Emperor, since — we repeat — it would be unworthy of Him to undermine the foundations of the Turkish Empire by the shameful and blameworthy action of a secret society.”10

Ypsilantis duly crossed the border on Feb. 21, 1821, and raised the standard of revolt in conjunction with some local Christian leaders. But this would be the high point for Ypsilantis — the Christian peasants in the Danubian Principalities never rose up en masse like Ypsilantis expected, perhaps not surprising since they were ethnic Romanians, not Greeks, and whatever resentments they had toward the Turks were matched by their grievances against the Greeks from Constantinople who the sultan had put in direct charge of the area. Ypsilantis’ own dithering weakened his military position further. Worst of all, though, Ypsilantis’s friend Tsar Alexander and his compatriot Kapodistrias categorically refused to support the Greek uprising with Russian armies. In an official letter to Ypsilantis, Kapodistrias wrote: “Russia is at peace with the Ottoman state… No help, either direct or indirect, will be accorded to you by the Emperor, since — we repeat — it would be unworthy of Him to undermine the foundations of the Turkish Empire by the shameful and blameworthy action of a secret society.”10

Above: “Alexander Ypsilantis crossing River Pruth into the Danubian Principalitie,” by Peter Von Hess, sometime after 1833. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ypsilantis and his small band were defeated, with the survivors slinking into exile, where Ypsilantis was promptly locked up by the Austrians. Similarly, hopes for Greek uprisings in Constantinople, maybe even an assassination of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, failed to come to pass. The Greek community in Constantinople would suffer grievously from reprisals, in fact, as the Sultan executed the Patriarch of Constantinople and dozens of other prominent Greeks as collective punishment for the Greek uprising.11

And yet, despite all this failure, the revolt plotted by the Eteria didn’t die out. The one place where the Greeks actually gained a foothold was in the peninsula in southern Greece called the Peloponnese. That’s the area of Greece that’s home to Sparta, and which gives its name to the classical Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. The Peloponnese was mostly poor and rural at this time. It had no major cities, and was plagued by local bandit chiefs called klephts.12

But the Peloponnese was far from Constantinople, overwhelmingly Christian, and lightly garrisoned by the Ottomans. So when the uprising began here, it wasn’t crushed. Greek bands swept through the peninsula, killing local Ottoman soldiers or driving them into their strongholds. Before too long the entire region was in Greek hands.13

Atrocities

I should pause here to cut through the usual sanitized words military historians use to describe the violence of war, like “killed” or “raided” or even “massacred.” The Greek uprising in the Peloponnese and elsewhere was intensely violent, and not merely against soldiers. I’ll give you some examples, and be warned this next section is going to discuss some fairly unpleasant things, including torture and sexual violence. If you want to avoid this, just know that there were widespread atrocities on both sides, and skip ahead to 18:45.

When the Greeks of the Peloponnese rose up in rebellion in the spring of 1821, mobs of ordinary Greeks turned on their Turkish neighbors in a few weeks of slaughter. Families living alone were murdered and their homes burned down on top of them. Some Turkish civilians barricaded themselves and negotiated a surrender, but the terms were usually disregarded and the victims slaughtered as soon as the gates were open. The men were slaughtered, anyway — women and children might be captured and sold as slaves instead. Captive soldiers might be publicly tortured before being killed. We’re told of the crew of one Turkish sailing vessel, captured by Greek ships, who were paraded through the streets in triumph and then literally roasted to death over fires on the beach.14

Above: Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople’s body being thrown into the Bosporus after being hanged, by Peter Van Hess. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Ottomans were equally brutal, if not more. And as with the Greeks, in part this violence came on direct orders from leaders, and in part it was from ordinary soldiers and civilians eager for blood. When the Sultan ordered the hanging of the Patriarch and other leading Greeks as punishment for the uprising, this was accompanied by state-encouraged mob violence. In a speech, Sultan Mahmud II addressed his Muslim subjects, calling on them to carry arms and “behave as battle-ready defenders of the faith.” His government also distributed guns to Muslims in Constantinople. Unsurprisingly, what happened next was gangs of Muslim citizens as well as common soldiers roaming the streets, murdering Greeks they encountered in cold blood. One westerner in Constantinople wrote of watching a man walking down the street in front of him casually stab a Greek to death, wipe off his sword, and then walk into a café for a smoke. Hundreds of Greeks were murdered in mob violence, and many more fled the city. Sultan Mahmud officially urged people not to attack innocents, but also publicly congratulated the perpetrators of massacres.15

On a grander scale, later in the war, were the massacres on the Aegean island of Chios. Chios was home to around 100,000 mostly Greek residents, and they publicly refused to join the rebellion. But when rebels from the nearby island of Samos landed a force to attack the Turkish garrison there, the Ottomans responded with overwhelming violence. Not only did the Ottoman fleet land with orders to make an example of the island, but thousands of armed civilians crossed over in small boats to join in the killing. Tens of thousands were killed, and more than 40,000 Greek women and children were sold into slavery — so many that the slave market at Constantinople was flooded and the price of slaves crashed.16

On a grander scale, later in the war, were the massacres on the Aegean island of Chios. Chios was home to around 100,000 mostly Greek residents, and they publicly refused to join the rebellion. But when rebels from the nearby island of Samos landed a force to attack the Turkish garrison there, the Ottomans responded with overwhelming violence. Not only did the Ottoman fleet land with orders to make an example of the island, but thousands of armed civilians crossed over in small boats to join in the killing. Tens of thousands were killed, and more than 40,000 Greek women and children were sold into slavery — so many that the slave market at Constantinople was flooded and the price of slaves crashed.16

The massacre at Chios, by Eugène Delacrois, 1824. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Historians attribute the viciousness of this war — a viciousness that appalled even veterans of the devastating Napoleonic Wars — to several factors. You had the religious element of the war, coupled with propaganda on both sides that dehumanized the other. Both sides believed that adherents of the opposing religion “had no rights and need only be spared if they had some commercial value.”17

The widespread institution of slavery in the Eastern Mediterranean at the time meant that taking women and children as captives could be valuable for fighters. Female captives were often subject to sexual violence. Sometimes young boys were, too. Boys were also usually forcibly converted to the religion of whichever side had captured them, which included being either baptized or circumcised, depending on the captor.18

Culturally, both the Greeks and the Turks at the time tended to ascribe to a cultural ethos of collective punishment — they “saw nothing strange in the idea of taking revenge on a community as a whole for wrongs done by a few members.”19

On a personal level, the combination of historical grievances and years of warfare meant individual soldiers on both sides were often fired by a deep desire for revenge — even if that revenge was taken on helpless civilians, or soldiers who had surrendered on the promise of good treatment.20

Beyond these structural factors, both the Greeks and Turks used atrocities strategically. For the Ottomans, the hope was to use terror to deter future rebellion, and compel the surrender of fighters currently under arms.21 For the Greeks, massacres of Muslims were a way to push their moderate compatriots off the fence — because everyone knew the Ottomans would retaliate indiscriminately, a massacre could force the locals to fight because the Ottomans would try to kill them either way.22

All this combined to create a system of dueling, escalating atrocities on both sides. By the summer of 1822, just over one year into the war, more than 50,000 people had died in the revolt — and only a tiny fraction of those had died in actual combat. The rest were killed in one-sided massacres.23

The Philhellenes

Word of these massacres filtered back to France and other parts of Europe, but in a slow, uneven fashion. In general news from Greece took about two months to reach Paris, and when it did arrive it was often uneven, misleading, or completely fabricated. In general, the stories that reached France were extremely pro-Greek in bias — stories of heroic rebels and villainous Turks.24 It was catnip for people who had been raised on the stories of the ancient Greeks — and especially for Frenchmen who felt either oppressed or bored by the conservative, un-martial rule of Louis XVIII.

The easiest burst of sympathy came in the form of writing. A flood of pamphlets flew off the presses. So did more than 128 separate books of pro-Greek poetry between 1821 and 1827 alone, starting with nine in 1821 and another 18 in 1822. (St. Clair notes that most of these poems — often by amateurs carried away by their passion — are of little literary merit besides as evidence for public opinion.)25

But some people were so moved by sympathy for the Greeks that they did more than write. At first a trickle and then a steady stream of Frenchmen joined people from across Europe in packing up their lives and heading to Greece to join the fight.

This account from a Danish student captures the viewpoint of a certain type of so-called “Philhellene,” or “lover of the Greeks”:

A kind of warlike enthusiasm took hold of me and was daily fired by newspaper descriptions of the fighting between the Greeks and the Turks… I had learned to admire the Greeks from my school days, and how could a man inclined to fight for freedom and justice find a better place than next to the oppressed Greeks?26

Other Philhellenes had more political reasons to go. In the repressive environment of 1820s France, there were plenty of people whose political leanings made it advisable or even necessary for them to travel abroad. In France that included plenty of former officers in Napoleon’s army — especially after the summer of 1821, when news arrived that Napoleon had died, putting a final end to hopes that the emperor might stage a second return.27

The Bourbon government knew that many of these Frenchmen seeking to join the Greek cause were politically dangerous. But it pursued a very ambivalent policy. While Austria closed its ports to departing Philhellenes and Prussia censored philhellenic pamphlets, France did nothing.28 Sure, it officially supported the policy of Austria’s foreign minister Metternich that the Greeks were in illegal rebellion against their legitimate Ottoman sovereigns, but it also let volunteers leave for Greece with a wink and a nod. The port city of Marseilles was the only major Mediterranean port that Philhellenes could use, and it was soon filled up with a rotating cast of volunteers waiting for ships to send them off to Greece.29 The idea, St. Clair writes, was to “run several contradictory policies at the same time in the confident expectation that they could not all fail” — either French arms would help secure the glory of Greece, or French diplomacy would uphold the balance of power in Europe. Either way, France wins — or so the thinking went.30

That’s not to say the French authorities were completely hands-off. The police infiltrated the Philhellenes with informants to keep informed of any developments. And they had good reason to! The first big wave of philhellenic volunteers started assembling in Marseilles in late 1821 and early 1822. If you’ve got a really good memory, you might remember that January 1822 was right when the Carbonari uprisings I covered back in Episode 23 started erupting around France. At least some of the Carbonari looked at the collection of idealistic, disaffected liberals gathering in Marseilles to go support revolution overseas and saw a prime recruiting ground. They encouraged the Philhellenes there to “postpone their trip to Greece to undertake a greater task in France.” But as was usually the case with these Carbonari plots, someone talked, the affair was busted up and the ringleaders were arrested.31 Louis’s government might have been ambivalent about the Greek Revolution, but revolution at home was an entirely different matter.

On top of the true believers and the political exiles was a third group of philhellenic volunteers: the hustlers. Wars offered both danger and an opportunity to win fame and fortune. Readers of The Count of Monte Cristo might recall one dastardly character who made his fortune by stealing the treasure of an Albanian warlord named Ali Pasha. Ali Pasha’s betrayal by a French officer was an invention of Alexander Dumas, but Ali Pasha was a real person, and so were amoral adventurers traveling to Greece to seek their fortune.32

Not all of these hustlers had schemes worthy of adventure stories, of course. A volunteer named Baron Friedel von Friedelsburg talked endlessly about his great castle in Denmark, until a real Danish lord showed up in Corinth and exposed him as a fraud. A Frenchman called Mari had been a drum major in Napoleon’s army, but pretended to be an officer — until he vanished and later turned up commanding a unit of the Egyptian army under the name Bekir Aga.33 An American philhellene named Lt. William Townsend Washington falsely claimed to be George Washington’s nephew.34 A young man appeared at the Stuttgart Greek Society, claiming in sign language to be a deaf and mute prince named Alepso from the Greek city of Argos. He satisfied local experts and was sent off to Greece in style; it was only after “Alepso” reached Greece that he got drunk and started speaking in German, revealing himself to be a watchmaker’s apprentice from Alsace. Mazower highlights the irony that the Philhellenes were familiar with mythical Greek princes from thousands of years ago, but had no clue that — as any modern Greek could have told them — there hadn’t been any princes from Argos for centuries.35

Reality sets in

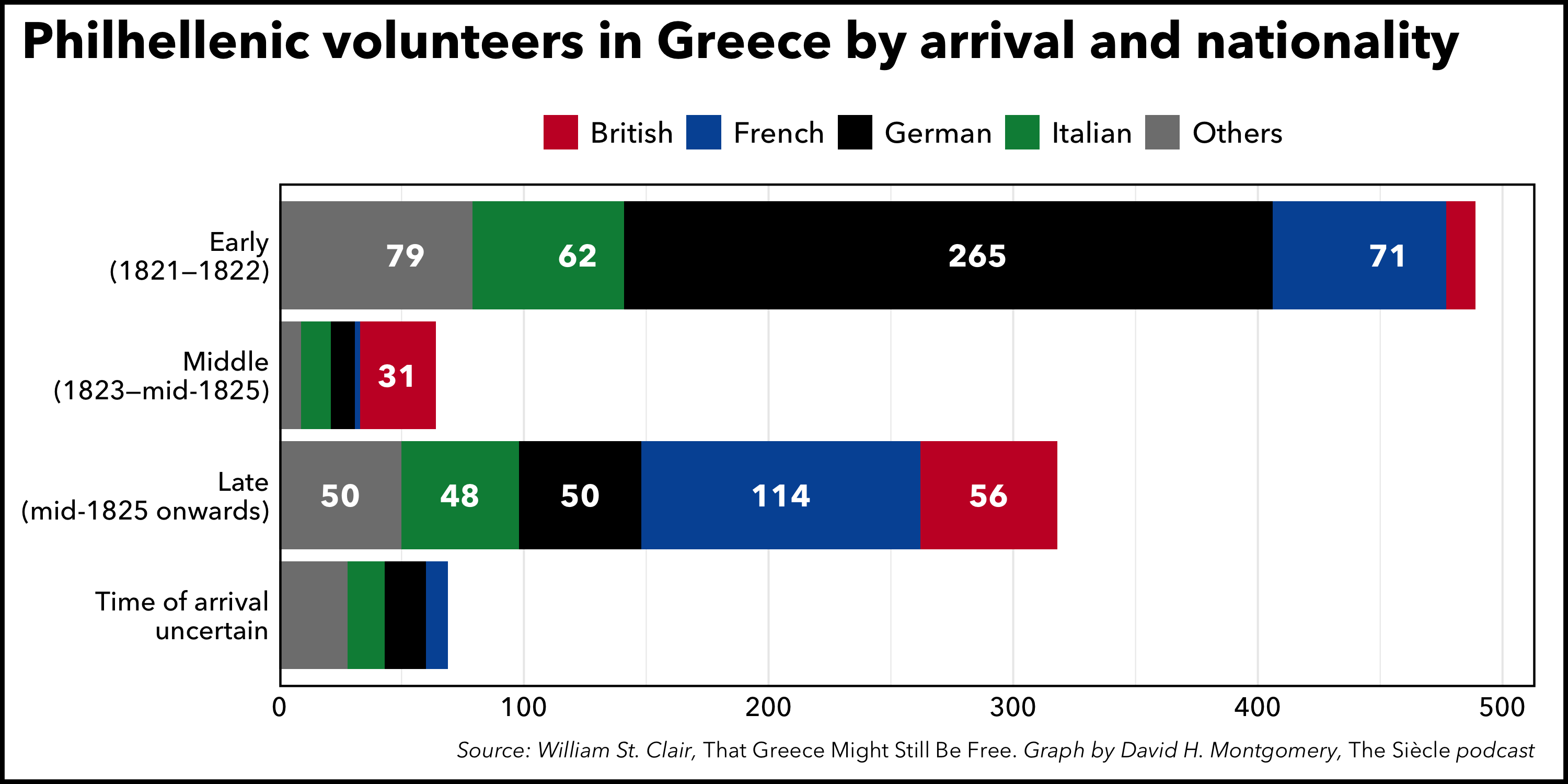

Over the entire course of the Greek War of Independence, St. Clair has identified 940 known Europeans who traveled to Greece to assist the rebellion. Of those, 196 were French, or about 20 percent.36

The actual experiences of these philhellenic volunteers once they reached Greece was almost universally discouraging and disheartening. For one thing, the situation on the ground was nothing like the picture painted by the reports that had filtered back west. These manifestos and third-hand reports had referenced great Greek victories that had never happened, at the hands of a Greek army that didn’t exist, commanded by a Greek government that had the dubious honor of barely existing. Distinguished European officers hopped off the boat expecting to be given a commission and command of a Greek unit — or even, depending on their pretensions, the entire Greek “army.” What they found instead was complete chaos. With some minor exceptions, there was no one to feed them, arm them, or pay them. There were no local regiments to command. There weren’t even — horror of horrors — any servants to carry their baggage off the boat.37

“Assembly of European officers coming to the aid of Greece in 1822,” author unknown, 1823. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Some turned back immediately. They were perhaps the wise ones. Others forged onward, enduring hostility from the locals who they expected to aid them, and outright attacks from opportunistic bandits. Some managed to reach central Greece where what passed for a Greek government was, and a small number even achieved what they came for, more or less: forming a European regiment to fight on behalf of the Greek cause. Unfortunately, after some minor successes, much of this unit was wiped out by Turkish cavalry in murky circumstances that may or may not have involved betrayal by a local Greek warlord.38 The Ottomans weren’t even the biggest danger the Philhellenes faced in Greece — outside of a few disastrous battles, most philhellenic fatalities were from disease. Of those 196 French Philhellenes, 60 of them would die in Greece — about 30 percent.39

Ultimately, there was simply a massive cultural gap separating the European officers from the Greeks they came to aid and lead. Napoleonic-era warfare featured organized units marching in unison and overpowering their enemies with massed firepower or terrifying charges. The highest martial virtue for these men was discipline: standing one’s ground in the line, reloading and firing over and over even as your comrades fell beside you. The Greek warriors tended to be guerrillas, who attacked in surprise raids and ran away whenever they faced a stiff counterattack. Both methods of warfare could be extremely effective in the right circumstances, but it proved nearly impossible for either side to understand the other. To the Europeans, the Greeks were cowardly and unreliable. To the Greeks, the Europeans were idiots who were going to get themselves killed.40 The Greeks were also mystified, I might add, by the European officers’ seemingly limitless drive to murder each other in duels of honor.41 And they often reacted with outright hostility when the Philhellenes intervened to protect Muslim captives from being killed or sold into slavery.42

Eventually, the surviving philhellenic volunteers began to filter back to Europe, where they met groups of enthusiastic volunteers sitting around Marseilles still waiting for their ship to Greece. That led to a fascinating clash, where the disillusioned philhellenic veterans tried to dissuade others from following in their footsteps — only to be roundly disbelieved and dismissed as cowards. Several French officers came back to Marseilles in April 1822, for example, and began loudly warning that the Greeks had no money or supplies and no organization — and also that the Greeks were committing terrible atrocities.43

The fact that the Greeks were massacring Turks as well as being massacred themselves was news to eager Philhellenes. The Greeks had a vastly better propaganda operation in Western countries than the Ottomans did. Indeed, the Ottomans didn’t even really bother getting their side of the story out, while pro-Greek pieces rolled off the printing presses. And these misleading pamphlets didn’t merely content themselves with making up Greek armies and Greek victories — they framed events in a way designed specifically to appeal to Europeans. For example, manifestos from Greek leaders were often loaded with references to classical battles and figures who most modern Greeks had never heard of. They also framed the Greek rebels as good liberals, like an early report that claimed that the Greeks had offered the Turks full civic and religious freedom in the new Greek state — a claim that could hardly have been more wrong about the Greeks’ intentions or actions.44

But even Europeans who didn’t trust propaganda and insisted on outside sources were prone to be misled. That’s because the initial Ottoman violence took place in Constantinople and other trading communities — cities with lots of Europeans in them. So the Turkish atrocities were “witnessed with horror by many Europeans and soon reported all over Europe.” In contrast, there were very few Europeans in Greece at the places where the Greeks were the killers, so little of it filtered back. When it did, as in the case of the returning Philhellenes, pro-Greek public opinion tended to either dismiss it or excuse it — for example, claiming that the Greeks’ unfortunate but understandable hatred had been provoked by centuries of oppression.45 Other supporters of the Greeks took steps to actively suppress this bad news, with at least one case where a returning officer was paid hush money to not publish his account of the Greek revolt.46

The revolution in brief

The twists and turns of the Greek War of Independence are beyond the scope of what I can cover in a single episode of a French history podcast, so I’ll just give you a bird’s-eye-view summary. The initial Greek successes on the Peloponnese led to a massive Ottoman counterattack that — to everyone’s surprise — ended up failing. This wasn’t because the Greeks defeated the Turks in open battle, but because disease and the hot Greek summer sapped the Turkish fighting strength until they had to retreat, at which point the Greek guerrillas ravaged them.47 The biggest Greek islands in the Aegean joined the revolt, bringing their fleets to bear against the Ottoman navy and merchant marine. Though outclassed by the larger Ottoman warships, the Greeks from islands like Hydra, Spetses and Psara evened the odds by using fireships — flaming hulks packed with flammable or explosive materials and sent drifting into the enemy fleet.48

The twists and turns of the Greek War of Independence are beyond the scope of what I can cover in a single episode of a French history podcast, so I’ll just give you a bird’s-eye-view summary. The initial Greek successes on the Peloponnese led to a massive Ottoman counterattack that — to everyone’s surprise — ended up failing. This wasn’t because the Greeks defeated the Turks in open battle, but because disease and the hot Greek summer sapped the Turkish fighting strength until they had to retreat, at which point the Greek guerrillas ravaged them.47 The biggest Greek islands in the Aegean joined the revolt, bringing their fleets to bear against the Ottoman navy and merchant marine. Though outclassed by the larger Ottoman warships, the Greeks from islands like Hydra, Spetses and Psara evened the odds by using fireships — flaming hulks packed with flammable or explosive materials and sent drifting into the enemy fleet.48

Above: “The Burning of the Turkish Flagship by Kanaris,” by Nikiforos Lytras, circa 1873. Konstantinos Kanaris was a famous Greek fireship admiral. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The high point of the Greek revolt was probably in early 1824. At that time, the Greeks had beaten back several Ottoman attacks and were enjoying a string of successes at sea, when a ship arrived from England with a game-changing gift for the shoestring rebellion: a cargo hold full of gold, the proceeds of a loan raised in Britain for the fledging Greek government.

But with the Ottomans temporarily defeated, this financial lifeline was swiftly put to a less noble use: one faction of Greeks secured possession of the loan and used most of the money to defeat their rivals in a civil war.49

The folly of this course became clear the next year, when a fleet belonging to Muhammad Ali landed an army in the southwestern Peloponnese.

The Egyptian Intervention

So right now you’re probably asking yourself, “Wait, who’s Muhammad Ali?” Or possibly you’re wondering when the famous boxer acquired a time machine. In either case, it’s time to properly introduce you to one of the most important men of this era.

Muhammad Ali, also transliterated as Mehmet Ali, was born in 1769 in what is today Greek Macedonia. He was from an Albanian family and soon entered the Ottoman military. In this role, Ali was an officer in a 1801 Ottoman expedition to retake Egypt from Napoleon’s French invasion force. After some complicated events, Ali launched a coup in 1805 that left him as the effective ruler of Egypt — nominally loyal to the sultan, but nearly independent in practice.50

Muhammad Ali, also transliterated as Mehmet Ali, was born in 1769 in what is today Greek Macedonia. He was from an Albanian family and soon entered the Ottoman military. In this role, Ali was an officer in a 1801 Ottoman expedition to retake Egypt from Napoleon’s French invasion force. After some complicated events, Ali launched a coup in 1805 that left him as the effective ruler of Egypt — nominally loyal to the sultan, but nearly independent in practice.50

Right: Muhammad Ali, viceroy of Egypt, 1841, by Auguste Couder. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And a cornerstone of Ali’s rule as Viceroy of Egypt was a close partnership with France. Those ties had transcended regimes — Ali was close to both Napoleon and the Bourbons. This was bigger than politics — it was geopolitics. Frenchmen who saw eye to eye on little else agreed that an alliance with Egypt was in France’s best interests.

The special relationship between Muhammad Ali and France began, if a certain anecdote is true, all the way back in 1804, before his coup. At that time, allegedly, Ali attended a banquet at the French consulate in Cairo, where some silverware went missing. Ali was blamed, but French diplomat Mathieu de Lesseps stuck by the man he’d identified as a strong potential leader and exonerated him.51 This story may or may not be true, but this mention of it definitely counts as foreshadowing.

In particular, France proved to be Muhammad Ali’s partner in his biggest project: westernizing Egypt. He was a great admirer of Napoleon, and quickly launched administrative and economic reforms.

I should be clear here, though, that Ali’s goal was primarily a modern, westernized state — not a westernized nation. Even as he sought to upgrade his government and military, he insisted on remaining an absolute monarch. Ali constructed his grand projects with huge brigades of conscripted peasant laborers, many of whom died under terrible working conditions.52 He sent young Egyptians abroad to learn European languages and techniques — but ordered them to remain aloof from European culture, and above all not to get ideas about bringing European-style liberalism back to Egypt along with European-style armies.53

In addition to sending Egyptians to Europe, Muhammad Ali also brought Europeans to Egypt. And in both cases, his primary partner was France. A French doctor was put in charge of public health. A French engineer built gunpowder factories and signal towers. Most prominently of all, a Frenchman named Joseph Sève became the “organizational mastermind” of Ali’s new army.54

In addition to sending Egyptians to Europe, Muhammad Ali also brought Europeans to Egypt. And in both cases, his primary partner was France. A French doctor was put in charge of public health. A French engineer built gunpowder factories and signal towers. Most prominently of all, a Frenchman named Joseph Sève became the “organizational mastermind” of Ali’s new army.54

Left: Muhammad Ali (center) with his son Ibrahim Pasha (left) and their military advisor Joseph Sève, alias Soliman Pasha. Author unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sève was one of thousands of devoted Bonapartist soldiers who found themselves out of work after Waterloo. We’ve already seen how a number of officers in the same situation found themselves joining the Greek cause. Sève went to Egypt, and threw himself wholeheartedly into Muhammad Ali’s service. Unlike most Europeans working for Muslim rulers, Sève converted to Islam and adopted the name “Soliman Pasha.” He hit it off with Ali and worked to train six regiments of modern French-style infantry for Ali’s army.55

These French experts were freelancing, but the Bourbon government gave more official support to Ali and his modernizing project. Most notably, in the early 1820s, France agreed to sell Ali state-of-the art naval frigates. Indeed, philhellenic volunteers setting sail from Marseilles to fight for Greece could see Egyptian ships being built in the shipyards there — ships that would soon used to suppress that same rebellion.56

Early on, Ali showed little interest in the Greek revolt. What interest he did show was positive — a far-off rebellion that would keep his nominal overlord, Sultan Mehmed II, distracted. But eventually Mehmed came to Ali with a tempting offer: if he crushed the Greeks, he could add their lands to his own.57 The French apparently tried to dissuade Muhammad Ali from involving himself in Greece but found that all their aid only gave them limited influence over Ali’s actions.58

That takes us to February 1825, when Muhammad Ali’s son59 landed an army in Greece. The Egyptians had already suppressed Greek rebels on Crete, and bypassed attempts by Greek ships to stop his armada at sea. On land, Soliman Pasha’s new French-style regiments mowed over bands of veteran Greek guerrillas and before long had occupied much of the Pelonnese.60

Byron

The prospects of Greek independence seemed dimmer than ever as the calendar turned to 1826. Or at least, that was the view on the ground in Greece. As was so often the case during this revolution, affairs looked rather different back in Europe — and especially in France. As it turned out, as the Hellenic cause fell back, Philhellenism was surging forward.

Perhaps the most sensationalistic development had happened back in 1824, when a ship sailed up to the swampy Greek town of Mesolonghi bearing one of the most famous — or infamous — men of the age: Lord Byron.

The renowned Romantic poet was acquainted with the region, and Byron’s 1812 poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage was a huge part of the prewar philhellenic literature that had primed Europeans to sympathize with the Greeks. Now, both bored and idealistic, Byron had returned to lend his body and fortune to the Greek cause.

Unfortunately for Byron, his direct contribution ended up being fairly limited. Within a few months Byron fell ill, and soon he was dead — though whether what killed him was the disease or his doctors’s frequent use of bloodletting as treatment is left to speculation.61

Lord Byron on his deathbed, by Joseph Odevaere, circa 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Fortunately for the Greeks, the death of one of Europe’s most famous men in the Greek cause was a public relations coup. As Mazower put it, “Nothing [Bryon] had managed to achieve in the short time he spent in Mesolonghi rivaled the impact of his death.” In death the controversial poet — still the center of attention, even in death — was transformed into a romantic hero, the myth eclipsing the man.62

A flood of hack biographies immediately streamed off the presses by people claiming to have been Byron’s closest companions. Many of these were published in France, where Byron was hugely popular.63 There were at least 14 books on Byron published in France in 1824 alone, along with a tragedy about the poet that the Paris Opera hurriedly threw together. And along with Byron, the French went wild for the Greek cause.64

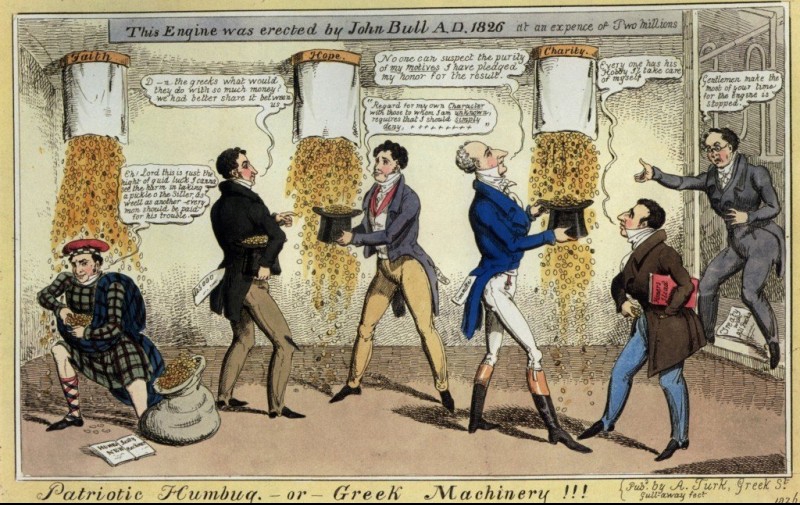

France goes philhellenic

In their Philhellenism, the French were actually late arrivers. The initial surge of enthusiasm for the Greeks back in 1821 and 1822 had been focused in Switzerland and various German states. When that wave of fundraising and volunteers faded, the British in turn took the lead, contributing that big loan I mentioned earlier. British enthusiasm in turn faded as it became clear the proceeds of the loan had been largely wasted and that the investors were likely to lose their money.65 By 1825, it was the French turn to Greek out.

An 1826 British political cartoon attacking various figures for appropriating money raised to help the Greeks for themselves. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The usual suspects in France had always been philhellenic — liberals, classicists, etc. But the movement had always stayed limited to that base. France’s right-wing governments in this time had officially supported the Ottomans’ rights to suppress rebellion, however ambivalently they enforced this policy. The Greek revolution’s origins in secret societies may have played a role, too; in the early days royalist newspapers published articles that “fulminated against the spirit of Carbonarism having invaded the East.”66 Plus France had plenty of domestic distractions during this time, from its own Carbonarist rebellions to the invasion of Spain in 1823.

By 1824 and 1825, however, those issues had largely faded away. And Philhellenism started to make inroads into new parts of French society: aristocratic royalists.

One key move came from a figure I’ve talked about a lot on this podcast: Chateaubriand. The author and statesman had visited Greece back in 1806,67 and had something of a romantic spirit, even well into his 50s. Then, in 1824, Louis XVIII and his prime minister Joseph Villèle fired Chateaubriand as France’s foreign minister — I covered that in Episode 25. This meant two things: Chateaubriand had a lot more free time, and he was no longer obligated to follow France’s pro-Turkish policy. He promptly took up the Greek cause — but using language that conservative royalists at the time could appreciate.

One key move came from a figure I’ve talked about a lot on this podcast: Chateaubriand. The author and statesman had visited Greece back in 1806,67 and had something of a romantic spirit, even well into his 50s. Then, in 1824, Louis XVIII and his prime minister Joseph Villèle fired Chateaubriand as France’s foreign minister — I covered that in Episode 25. This meant two things: Chateaubriand had a lot more free time, and he was no longer obligated to follow France’s pro-Turkish policy. He promptly took up the Greek cause — but using language that conservative royalists at the time could appreciate.

Right: “Chateaubriand Meditating on the Ruins of Rome,” by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, after 1808. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Chateaubriand’s dilemma as a royalist Philhellene was how to justify revolution in Greece without justifying it in Western Europe. He found a solution to this problem that was genuinely effective — though to modern ears his rhetoric here comes off as rude or offensive. To distinguish between revolution here and there, Chateaubriand emphasized cultural and religious differences — and specifically, he attacked the culture and religion of the Muslim Ottomans.

The revolutions in Spain and Naples, Chateaubriand argued, were wrong because men were targeting legitimate rulers. But the Ottoman sultans lacked that legitimacy, Chateaubriand argued; theirs was a mere despotism, and they had forfeited the allegiance of their Christian subjects by oppressing them.68

“Will Christendom calmly allow Turks to strangle Christians?” Chateaubriand wrote. “And will the Legitimate Monarchs of Europe shamelessly permit their sacred name to be given to a tyranny which could have reddened the Tiber?”69

With this distinction, Chateaubriand helped royalists justify supporting Greece. He and others built up an argument emphasizing not the revolutionary tradition and the glories of ancient pagans, but Christian solidarity and the spirit of the Crusades.

There’s a lot to be done to unpack the assumptions and assertions Chateaubriand is using, and the degree to which they matched up with the reality of the Ottoman state. I won’t derail this podcast further with a deep dive into political theory here, though. The important thing is, even if you find what Chateaubriand said to be offensive or incorrect, it worked. Conservative royalists who had previously been skeptical of the Greek cause now found themselves coming on board, due in part to arguments like Chateaubriand’s.

It’s also important to add, before I go on, that Chateaubriand’s pro-Greek arguments in this time also included some virulent anti-Black racism in addition to attacks on Islam. I didn’t want to repeat that in this episode, but for full disclosure I put a disturbing quote from him online at thesiecle.com/episode30, in footnote 70.70

The other notable factor that helped spur broader support for the Greeks was that they started to lose. Real or imagined stories of Greek triumphs had helped inspire Philhellenes earlier in the war. But hearts across the political spectrum warmed to tales of real or imagined atrocities that the Greeks were suffering at the hands of the ascendant Ottomans and Egyptians.

And some of these atrocities were definitely real. While Muhammad Ali’s invading army had originally been quite restrained by the standards of warfare in the region, trying to persuade the Greeks to surrender, the Egyptians gradually turned to harsher measures. In this they were spurred on by the Greeks, who repeatedly massacred Muslim prisoners during the war. After failing to beat the Ottomans in head-on battle, the Greeks fell back to guerilla warfare — which provoked the kind of scorched-earth campaign that armies often use against guerilla forces. Egyptian troops seized crops and destroyed homes. Most notable at the time was the practice of selling captives into slavery. Both sides did this, but it was the stories of Greeks sold into slavery as the Turks and Egyptians advanced that stirred outrage in Paris.71

And some of these atrocities were definitely real. While Muhammad Ali’s invading army had originally been quite restrained by the standards of warfare in the region, trying to persuade the Greeks to surrender, the Egyptians gradually turned to harsher measures. In this they were spurred on by the Greeks, who repeatedly massacred Muslim prisoners during the war. After failing to beat the Ottomans in head-on battle, the Greeks fell back to guerilla warfare — which provoked the kind of scorched-earth campaign that armies often use against guerilla forces. Egyptian troops seized crops and destroyed homes. Most notable at the time was the practice of selling captives into slavery. Both sides did this, but it was the stories of Greeks sold into slavery as the Turks and Egyptians advanced that stirred outrage in Paris.71

The dramatic focus of all these building emotions was the city of Mesolonghi, where Byron had died. Starting in April 1825, the Ottomans and Egyptians put this vital and symbolic city under siege. Despite being massively outnumbered and low on supplies, defenders kept holding out for month after month. Finally, however, in April 1826, after nearly a full year, the city fell. Many of its defenders managed to escape, but some 3,000 to 4,000 women and children were taken as slaves.72 Mesolonghi was a crushing victory over one of the last Greek towns still in rebellion — but it would prove to be a Pyrrhic victory for the Ottomans.

Above: “Greece on the ruins of Mesolonghi,” by Eugène Delacroix, 1826. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license by Flickr user dalbera, via Wikimedia Commons.

Musical philhellenism

At almost the exact same time that the starving defenders of Mesolonghi were falling to the Ottomans, better-fed Parisians over a thousand miles away were making their own philhellenic gesture: a benefit concert.

That sounds like a joke, but the concert was real — and for what it represented, it’s very serious. Held on April 28, 1826, the benefit concert was organized by the duchese de Dalberg, a member of the new Napoleonic nobility. And at first Charles X’s government discouraged this event, seeing it as a liberal project. But sympathy for the Greeks was spreading beyond just liberals by this point. In the words of the author and journalist Stendhal, “suddenly a number of ultra ladies of rank began to evince symptoms of compassion, and in a day or two it became quite the fashion to patronize the concert.”73 And not just patronize, but participate — the singers at the concert were aristocratic ladies, performing a mix of pro-Greek songs and opera standards.74

Charles’s government remained officially opposed to the concert. The composer Gioachino Rossini, who had been brought to Paris on a government contract, was apparently ordered not to conduct the concert, for example. But the tides of elite opinion were moving in a sharply pro-Greek direction. Rossini, banned from conducting the concert, made his sympathies known by conducting the rehearsal. The police apparently sent a spy to take down the names of everyone who attended the concert, but Stendhal quipped that they “would have had an easier job taking the names of the high society who had stayed at home.”75

Charles’s government remained officially opposed to the concert. The composer Gioachino Rossini, who had been brought to Paris on a government contract, was apparently ordered not to conduct the concert, for example. But the tides of elite opinion were moving in a sharply pro-Greek direction. Rossini, banned from conducting the concert, made his sympathies known by conducting the rehearsal. The police apparently sent a spy to take down the names of everyone who attended the concert, but Stendhal quipped that they “would have had an easier job taking the names of the high society who had stayed at home.”75

Gioachino Rossini, by Constance Mayer, 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The benefit concert raised some 30,000 francs for the aid of the Greeks, but its real significance wasn’t in the money. It was as a catalyst for pro-Greek opinion in all aspects of the French elite. A philanthropic organization, the Philanthropic Society in Favor of the Greeks,76 counted among its supporters famous liberals like the Marquis de Lafayette and Benjamin Constant, moderate reformers such as the Duc de Broglie and the Duc d’Orléans, and Ultras like Chateaubriand and the Duc de Fitzjames — known as one of the most “enflamed” supporters of the Comte d’Artois before he took the throne as Charles X.77

The Philhellenism of Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans, deserves a brief tangent. Louis-Philippe was the king’s cousin, and for a long time had fairly openly coveted the French throne. By 1825 or so, though, any chance that Louis-Philippe might inherit the throne seemed remote, after the 1820 birth of the so-called “Miracle Child”: the Comte de Chambord, Charles’ now 5-year-old grandson. I covered all that — including Orléans’s jealousy and despair — back in Episode 15.

That didn’t mean Louis-Philippe had given up on the prospect of securing a crown for his family. It just didn’t necessarily have to be the French crown. The chaos in Greece seemed to at least some people to offer an opportunity: the Greeks could form a kingdom with a royal Bourbon prince at the head: Louis-Philippe’s 11-year-old son, the Duc de Nemours. A French general was sent to Greece on a public mission from the Paris Greek Committee, with a secret mission to secure support for Nemour’s kingship, in return for French support for the Greeks. Just how much Charles and Villèle were actually on board with this plan is uncertain, but it was never wholehearted. They eventually washed their hands of the whole affair, and forced Louis-Philippe to disavow it, too.78

But if Charles and Villèle opposed a plan to put an Orléans prince on the throne of Greece, it was becoming increasingly difficult for them to oppose the Greeks.

The game is afoot

Joseph Villèle was a cold-hearted man who found Philhellenism a confusing distraction from the realities of balanced budgets. “Money does not like cannon fire,” he wrote once. Villèle’s boss, King Charles, had a more romantic spirit, and was openly sympathetic to the Greeks. But in correspondence throughout 1825 and 1826, Charles’s emphasis was finding a way to prevent open war between the Ottomans and other great powers.79

As the Greek revolution dragged on, however, both men found preventing that expensive war becoming increasingly difficult.

The ticking clock driving all of this from 1824 through 1827 is the steadily deteriorating position of the Greek rebels as Muhammad Ali’s army rolled through the Peloponnese. The more time passes, the more desperately the Greeks appear to need outside help, lest they face total disaster.

Meanwhile, philhellenic sentiment in France was steadily growing over this same time period, as we’ve discussed. Increasingly, Charles’s government was being hammered in parliament for not supporting the Greeks, from both the liberals and Chateaubriand’s faction of dissident Ultras.80

Under this escalating pressure, the French government made some quiet gestures of support to the Greeks. Police harassment of returning Philhellenes was lifted, and obstacles were removed for Philhellenes trying to depart from Marseilles. On the other hand, the French government was just as quietly increasing its support for Muhammad Ali. In 1824, Ali hit the French government with an awkward request to send an official delegation of military advisors to help train the army that everyone knew was about to attack the Greeks. This official delegation would join the existing French officers like Sève who had gone to Egypt as private citizens. The French opposed such an escalation — but also didn’t want to lose Ali as a client. They eventually agreed to send the delegation, but under a diplomatic fiction that they, too, were private citizens. In 1826, well into his invasion, Ali asked France for more modern warships — a request the French also felt obliged to grant.81

The final straw for Charles and Villèle was geopolitics. Early on in the Greek revolt, the great powers of Europe had all opposed helping the Greeks. For the British, that was because of a pro-Ottoman foreign policy. For Austria, Prussia and Russia, this was driven by an ideological policy supporting the rights of sovereign powers to suppress revolution — a policy that in the case of Tsar Alexander overrode both sympathy to the Greeks and rivalry with the Ottomans.82

By 1825, the situation had changed dramatically. The first straw happened in 1822, when Britain’s foreign minister Viscount Castlereagh died. His replacement, George Canning, had a somewhat different emphasis. Instead of Castlereagh’s conservative support for the Ottoman status quo, Canning thought he could use the Greek revolt to accomplish a subtler goal: to drive a wedge between Austria and Russia, and thus break up the so-called “Holy Alliance.” Austria’s chancellor Klemens von Metternich had supported the Ottoman right to suppress their rebels since the very beginning. By 1823, however, Tsar Alexander was wavering on his earlier policy of supporting the Ottomans.83

By 1825, the situation had changed dramatically. The first straw happened in 1822, when Britain’s foreign minister Viscount Castlereagh died. His replacement, George Canning, had a somewhat different emphasis. Instead of Castlereagh’s conservative support for the Ottoman status quo, Canning thought he could use the Greek revolt to accomplish a subtler goal: to drive a wedge between Austria and Russia, and thus break up the so-called “Holy Alliance.” Austria’s chancellor Klemens von Metternich had supported the Ottoman right to suppress their rebels since the very beginning. By 1823, however, Tsar Alexander was wavering on his earlier policy of supporting the Ottomans.83

Left: George Canning, by Thomas Lawrence, 1822. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This all came to a head in 1825, when Tsar Alexander sent a back-channel message to Canning suggesting a partnership to intervene on behalf of the Greeks.84 Canning leapt at the opportunity, and the two sides signed the Protocol of St. Petersburg in April 1826, the same month that Mesolonghi fell. (The treaty hadn’t been derailed by the sudden death in 1825 of Tsar Alexander, for his brother and successor, Tsar Nicholas, was an even bigger supporter of the plan.)85

This presented a diplomatic crisis for France. If Russia and Britain intervened together, they could use their force of arms to bolster their own influence in the region, at the expense of France’s interests. The French government was furious and filed a diplomatic protest about Britain leaving France out in the cold.86

But Canning’s goal here wasn’t to freeze out the French. It was to freeze out Count Metternich and the Austrians. He was open to French participation. Under pressures both foreign and domestic, so were Charles and Villèle. After extensive negotiations France joined Britain and Russia in signing the July 1827 Treaty of London. This was an agreement between the three powers to support Greek autonomy, though not yet actually full independence. If either side refused, then the three powers pledged to send fleets to the Aegean to enforce an armistice — though it included a caveat that this enforcement would not involve “taking any part in the hostilities between the Two Contending Parties.”87 This was, Mazower notes, a “diplomatic fudge — designed to satisfy both the British and French, who were determined to avoid a war, and the Russians, who insisted on some kind of credible threat.”88

Navarino

Events moved quickly after this. As expected, Sultan Mehmed II rejected this outside meddling in what he saw as his own internal affairs. Not only was it insulting, but Mehmed felt like he had already won. In June 1827, a full month before the Treaty of London, the Ottomans had won the siege of Athens — an even more symbolic victory than Mesolonghi had been. And it left the Greeks with only a handful of towns and islands left under their control.

Athens as it appeared circa 1834, from Otto Magnus Von Stackelberg, La Grèce: Vues pittoresques et topographiques, (Paris, Chez I. F. D’Ostervald, 1834). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Athens had fallen despite increasing support for the Greeks from outsiders, including a flashy French colonel named Charles Fabvier. And I hope you’ll forgive one last tangent before we reach the end here, because Fabvier has actually been all over our narrative in the background. Back in Episode 11, I talked about an alleged revolutionary conspiracy in the city of Lyons in 1817, and how liberal elements in the French government later claimed that the entire affair had been a false flag operation by Ultra officials. The author of that liberal report was Col. Fabvier, in his role as a senior military aide. Fabvier was involved in the definitely real liberal coup attempt of 1820 that I talked about in Episode 15. In the aftermath of that failed coup, as I mentioned last time, the Doctrinaire Duc de Broglie acted to protect senior liberal politicians by dropping charges against the one conspirator who was capable of implicating them. That “one conspirator”? No points if you guessed it was Charles Fabvier. You also don’t get any prizes for guessing that Fabvier was heavily involved in France’s Carbonari uprisings. In Episode 18, I mentioned how the French army invading Spain in 1823 was met by a group of exiled French soldiers, waving the tricolor flag and encouraging their countrymen to mutiny. That contingent of exiled French soldiers was commanded by… well, I don’t think you need me to spell it out.89

Athens had fallen despite increasing support for the Greeks from outsiders, including a flashy French colonel named Charles Fabvier. And I hope you’ll forgive one last tangent before we reach the end here, because Fabvier has actually been all over our narrative in the background. Back in Episode 11, I talked about an alleged revolutionary conspiracy in the city of Lyons in 1817, and how liberal elements in the French government later claimed that the entire affair had been a false flag operation by Ultra officials. The author of that liberal report was Col. Fabvier, in his role as a senior military aide. Fabvier was involved in the definitely real liberal coup attempt of 1820 that I talked about in Episode 15. In the aftermath of that failed coup, as I mentioned last time, the Doctrinaire Duc de Broglie acted to protect senior liberal politicians by dropping charges against the one conspirator who was capable of implicating them. That “one conspirator”? No points if you guessed it was Charles Fabvier. You also don’t get any prizes for guessing that Fabvier was heavily involved in France’s Carbonari uprisings. In Episode 18, I mentioned how the French army invading Spain in 1823 was met by a group of exiled French soldiers, waving the tricolor flag and encouraging their countrymen to mutiny. That contingent of exiled French soldiers was commanded by… well, I don’t think you need me to spell it out.89

Above: Charles Fabvier in Greek dress. Artist unknown, date unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

That probably gives you a good picture of Fabvier’s personality. He was tall, stern and determined, a career soldier and convinced liberal who had spent the last few years bouncing around from failed revolution to failed revolution. It’s no surprise that Fabvier showed up in Greece, too. Working diligently, Fabvier visited Greece to scout out the situation, returned to Western Europe to gather supplies and comrades, then came back to Greece in the immediate aftermath of the Egyptian invasion, when Greek leaders finally agreed on the necessity of recruiting a European-style army. Fabvier was appointed to lead this force, and it was a good choice. In a famous scene, Fabvier presented himself to his new Greek troops dressed in his full French military uniform, and declared that he was a Frenchman — but would now become a Greek. The next day, he appeared before them again in full Greek dress, and “thereafter he never wore anything else.”90 But as dashing and competent as Fabvier was, he was limited by the dysfunction of the Greek government. As Mazower notes, unlike Joseph Sève in Egypt, “Colonel Fabvier did not have a [Muhammad] Ali to back him.” He struggled with adequate supplies, and was often deployed poorly. He was willing to go try to relieve Mesolonghi, but the Greek government never found the ships to get him there.91 They did send him to try to resupply Athens, but he ended up trapped inside the siege. Other attempts to relieve Athens failed, and with victory unlikely, the garrison holed up in the Acropolis negotiated a surrender.92

When Fabvier and the other defenders of Athens surrendered in June 1827, they did so through the auspices of Admiral Henri de Rigny, commander of a French naval squadron stationed permanently in the Aegean. Involving Rigny in the surrender was a smart move; massacring a garrison after they had surrendered had been an all-too-common occurrence on both sides in this bloody war. Rigny managed to extricate the defenders and drop them off at the Greek camp.93

When Fabvier and the other defenders of Athens surrendered in June 1827, they did so through the auspices of Admiral Henri de Rigny, commander of a French naval squadron stationed permanently in the Aegean. Involving Rigny in the surrender was a smart move; massacring a garrison after they had surrendered had been an all-too-common occurrence on both sides in this bloody war. Rigny managed to extricate the defenders and drop them off at the Greek camp.93

Left: Admiral Henri de Rigny, by François-Gabriel Lépaulle, 1836. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But Rigny’s greatest role to play in the war was yet to come. After Sultan Mehmed rejected the offer of mediation, Britain, France and Russia turned to their navies to try to peacefully compel an armistice. Britain and France already had squadrons in the area, and the Russians dispatched a squadron to join them. Rigny, British Admiral Edward Codrington and Russian Admiral Lodewijk van Heiden94 got on well together, with all three agreeing that Codrington should take the overall lead.

The admirals first delivered their ultimatum to Muhammad Ali’s son Ibrahim, who was commanding the Egyptian army in Greece. They95 met with Ibrahim in the town of Navarino — modern-day Pylos — on the southwestern tip of the Peloponnese. There, after some back-and-forth, they got Ibrahim to agree to temporarily suspend military operations until he got further orders. But Ibrahim continued attacks on both land and sea — possibly irate that the allies were forcing him to stand down but not enforcing any such peace on Greek forces. Irate, all three admirals eventually agreed on a bold plan to show the Ottomans they meant business: they would sail directly into Navarino Bay, where a combined Ottoman-Egyptian fleet was moored.96 (My sources aren’t always clear which particular ships were Ottoman or Egyptian, so I’ll just refer to them all as Ottoman for simplicity’s sake.)

The fighting in what we call the Battle of Navarino began on Oct. 20, 1827, “almost by accident” — though it was hardly a great surprise that when so many heavily armed ships were so close to one another, with nervous or glory-hungry crew, that someone would have opened fire. The opening shots appear to have concerned an Ottoman fireship — those are the hulks that are lit on fire and then sent floating to the enemy fleet that I mentioned earlier. A British vessel sent a boat ordering the fireship to stand down. The Ottoman crew opened fire on the boat with small arms. That led the British frigate to open up with her cannons, which led other ships to join in. Before long there was firing up and down the line.97

When the battle began, the Ottomans had the advantage in ships, sailors and firepower, with 65 ships to the British-French-Russian fleet’s 27. But the allied ships were higher quality, and “vastly superior in preparation, experience and gunmanship.” Admiral de Rigny also took away a crucial asset from the Egyptian ships: their French military advisers, who were persuaded to withdraw rather than fire on French ships.98

What ensued was a one-sided slaughter over four hours. Most of the Ottoman fleet was either destroyed or disabled, with thousands of men killed. The allied fleet had 180 killed and 500 wounded, and didn’t lose a single ship (though a few were in rough shape). It was “the last great battle of the Age of Sail,” before steamships came to rule the sea.99 It also effectively ended the Greek War of Independence in a single day. After Navarino, the Ottomans and Egyptians were incapable of supporting armies in Greece, and all that remained was to negotiate a peace.100

“Sea battle at Navarino on October 20 1827,” by Ivan Ayvazovsky, 1846. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Negotiating that peace wasn’t nearly as simple as I made it sound just there, and France’s military involvement in the region isn’t done yet. But that’s a story for a future episode. Suffice it to say that Greece was on her way to independence. But neither France nor Britain was happy with their great victory. Both sides had wanted to support the Greeks and end the war, yes — but they didn’t want to annihilate the Ottoman navy. Both countries still felt that a strong Ottoman Empire was in their best interests. And France in particular wanted to build up the Egyptian military, not destroy the very frigates it had built for Muhammad Ali! The Russians, in contrast, were overjoyed. Within a few years, Russian armies would surge over the border in the Ninth Russo-Turkish War, settling unfinished business and grabbing some territory in the process. Sultan Mehmed and his advisors had believed the western threats were bluster and were horrified to learn of the battle. But Muhammad Ali astonished people by receiving the news with an even keel. Though his fleet had been sunk Ali saw the larger game: a disaster for the sultan was an opportunity for him. Muhammad Ali’s attempts to capitalize on this power-shift will also have to wait for another day.101

Greek soldiers in the Morea during the insurrection of 1829, by Théodore Leblanc, 1829. Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. Public domain.

I’m going to end things there. What you’ve just heard has only been a fraction of the story of the Greek War of Independence. Hopefully this story of an underdog inspiring Western sympathy from its surprisingly resilient military struggle against one of the world’s great powers will help you understand why I chose to release this episode now.

The Greek Revolution could justify an entire podcast series covering its twists, turns and personalities. You might want to learn more about the things I omitted or breezed past — like the brigand-turned-revolutionary Theodoros Koloktrones, Muhammad Ali’s indomitable son Ibrahim Pasha, the irascible genius Admiral Thomas Cochrane, the attempt by disciples of British philosopher Jeremy Bentham to turn Greece into a utilitarian paradise, the famous Albanian warlord Ali Pasha, the American revolutionary and humanitarian Samuel Gridley Howe, the daring Greek fireship Admiral Konstantinos Kanaris, and far more. If so, I again suggest you start with the two books that have proven indispensable: Mark Mazower’s 2021 The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe, and William St. Clair’s 1972 classic That Greece Might Still Be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence. Both are linked online at thesiecle.com/episode30.

If you don’t feel like reading, stay tuned to this feed. I’ll be releasing a bonus episode in a few weeks covering a topic that I had to cut for time: the impact of the Greek War of Independence on French art and music. Featuring a discussion of works by Eugène Delacroix, Rossini, Alexandre Dumas and more, you’re not going to want to miss it!

Most importantly, though, you’re going to want to go to intelligentspeechconference.com to buy your ticket for the online Intelligent Speech Conference on Saturday, June 25. Remember to use the coupon code “siecle” to save 10 percent.

Thanks again to all of you for listening, spreading the word on social media, and pledging as little as $1 per month on Patreon. I’d especially like to thank my newest patrons: Kunle Demuren, Fernando Campos, K.M.D., Daniel Levy, Michael Hankin, Andy Kirsch, Scott, Marguerite Guthridge, Alex, Andrew Coate and Aaron O’Brien. Apologies as always for my pronunciations.

Now I’ve got to wrap this up to work on my Intelligent Speech talk and the bonus episode on Philhellenic art. After that, though, everything I’ve been building to for the last half-dozen episodes will come to a head in Episode 31: The Election of 1827.

-

Mark Mazower, The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (New York: Penguin Press, 2021), xxx. The Ottomans did conduct a Census around 1831, their first in centuries, but because it was focused on ascertaining taxation and military manpower it only enumerated male residents. Even adjusting for this, the 1831 census was a dramatic undercount, producing a population estimate as much as four times smaller than modern historical demographers’ best guesses. Muslim subjects in particular appear to have been undercounted, since Christians were subject to a head tax that incentivized officials to accurately count them all. See Kemal H. Karpat, Ottoman Population, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 20-21. ↩

-

Karpat, Ottoman Population, 18-23. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, xxxiv. ↩

-

William St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2008), 13-15. ↩

-

Edgar Garston, Greece revisited, and sketches in Lower Egypt in 1840; with thirty-six hours of a campaign in Greece in 1825, Vol. 2 (London: 1842), 311. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, xxxiv. ↩

-

Karpat, Ottoman Population, 46. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, xxx. ↩

-

The preceding paragraphs all come primarily from Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 8-21. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 26-31. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 31-34. ↩

-

The Peloponnese was primarily called “Morea” at this time, a medieval name for the area. I’ve deliberately chosen to anachronistically use “Peloponnese” to help with listener comprehension. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 11-12. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 1-2. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 34-5. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 335-6. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 39. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free,, 9. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 25. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 184. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 34. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 11-2. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 92. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 51-2. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 53-5. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 67. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 222-3. Driving home the point, one of Napoleon’s nephews, Prince Paul Marie Bonaparte, died in Greece as a philhellenic volunteer. . ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 65. ↩

-

France would eventually close the port of Marseilles to Philhellenes, in Nov. 1822, apparently in reaction to the stories filtering back about the disastrous fates meeting so many of the Philhellenes. St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 125. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 57. ↩

-

Alan B. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes: The French Carbonari Against the Bourbon Restoration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), 96-100. ↩

-

Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo, translated by Robin Buss (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 853-61. Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 37-45, 119-21. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 89. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 280-1. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 224-5. ↩

-

The most common philhellenic nationality was Germany, accounting for 342 Philhellenes and 142 deaths. Overall 313 of the 940 known Philhellenes died, a great many from disease rather than hostile action. St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 356. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 82. St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 82. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 96-102. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 356. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 38-9. For more on these different modes of combat and the different martial virtues they require, see Bret Devereaux, “The Universal Warrior, Part IIA: The Many Faces of Battle,” A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, Feb. 5, 2021. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 83. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 239. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 76. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 23-4. ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 25. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 235-6. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 126-7. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 147-8. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 266. ↩

-

For background, see Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid Marsot, Egypt in the Reign of Muhammad Ali (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 24-74. ↩

-