Episode 31: The Election of 1827

This is The Siècle, Episode 31: The Election of 1827.

Welcome back! As I record this, it’s election season here in the United States. That’s what we’re going to talk about today — not elections in 2020s America, of course, but a fascinating election in 1827 France.

I’ve arranged this episode specifically so that people new to the show can follow along without missing too much — though longtime listeners will appreciate how separate threads we’ve been following for years will all come together in this 1827 showdown.

France in the 1820s was run by the Bourbon Restoration, a constitutional monarchy ruled by the relatives of the guillotined King Louis XVI. By today’s standards, we’d probably refer to this government as a semi-authoritarian regime. It held elections which were questionably free and definitely not fair. The only people eligible to vote were a handful of France’s richest men, and the elected Chamber of Deputies was balanced by the Chamber of Peers, made up of appointed aristocrats. While this parliament had some say, the king and his government had a powerful hand to shape policy or even rule by decree. The government used frequent newspaper censorship and an extensive network of secret police to keep an eye on potential opponents.

But despite all this, the Bourbon Restoration wasn’t a pure dictatorship. The regime mostly followed its constitution, the Charter of 1814, albeit with occasional exceptions. Parliament could and did reject the king’s proposals. And despite abundant manipulation and repression, the government didn’t always win elections.

That’s what we’re going to talk about today: how France’s beleaguered opposition made a serious run at the 1827 elections. But before we get there, we’ve got to dive into some background.

The Election of 1824

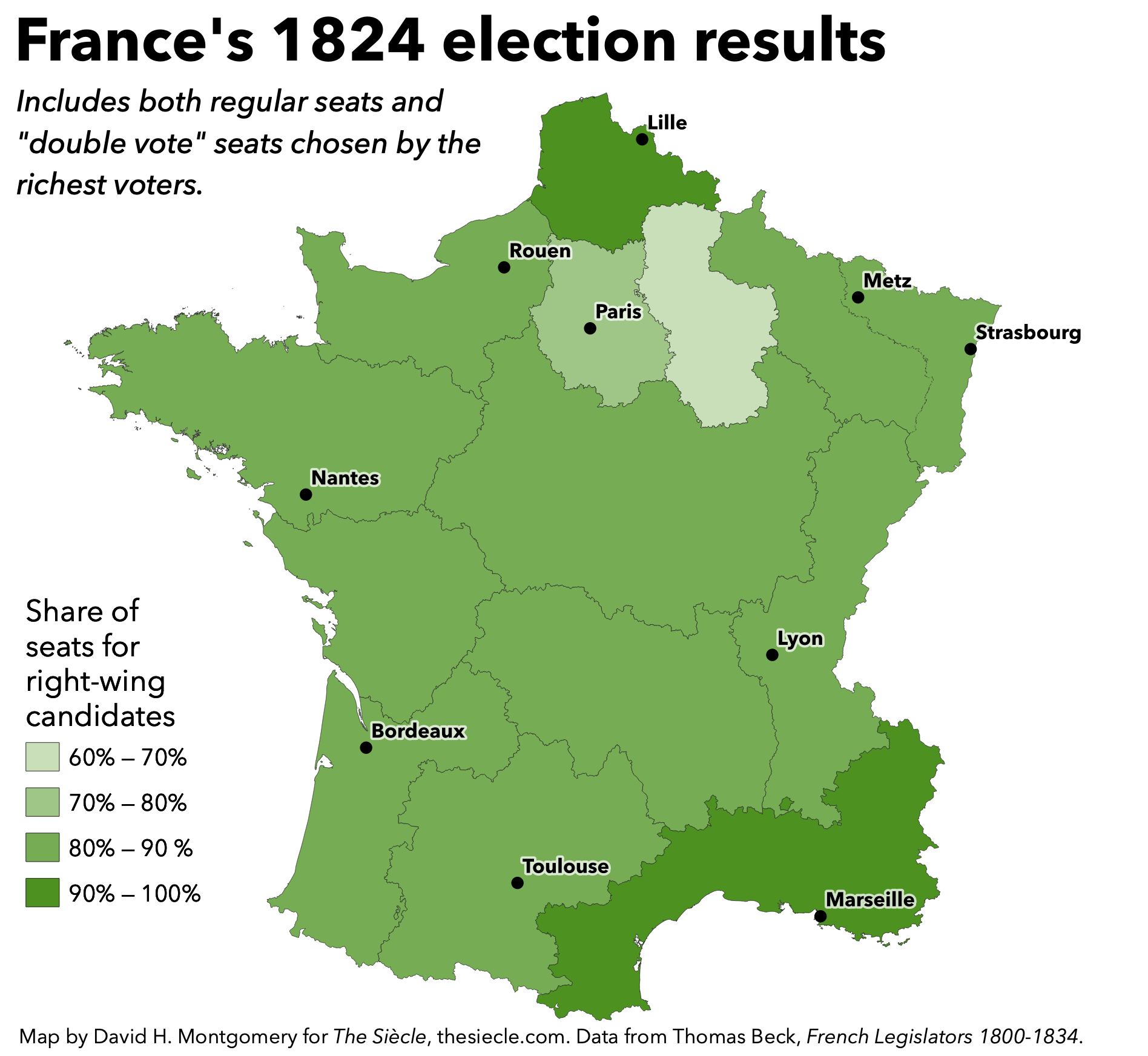

The Election of 1827 followed three years after a round of elections in 1824. These had been won overwhelmingly by candidates who were arch-conservative royalists — often referred to as “ultraroyalists” or simply “Ultras.”

The Election of 1827 followed three years after a round of elections in 1824. These had been won overwhelmingly by candidates who were arch-conservative royalists — often referred to as “ultraroyalists” or simply “Ultras.”

In one sense, it’s not a surprise that the Ultras won big in 1824. France had an incumbent ultraroyalist government that had delivered a strong economy and had successfully managed an invasion of neighboring Spain.1 Meanwhile the opposition liberals had been discredited when some of them supported a series of failed uprisings — the “Carbonari” conspiracies I talked about in Episode 23.

Above: François Séraphin Delpech, after Jean Sébastien Rouillard, “Jean-Baptiste Guillaume Joseph, comte de Villèle,” c. 1815-1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But while the Ultras might have won anyway, the ultraroyalist prime minister Joseph Villèle didn’t leave anything to chance: he used all the levers of state power at his disposal to tilt the field in his faction’s favor.

Chief among those was a biased electoral system that had been revised in 1820. While voting was limited to the richest 1 percent of French men,2 the new “Law of the Double Vote” empowered the richest quarter of that 1 percent with an even bigger say. This top 0.25 percent — who were disproportionately ultraroyalist — could vote as usual for the regular 258 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, but then also got to vote for a second set of 172 seats.3

Chief among those was a biased electoral system that had been revised in 1820. While voting was limited to the richest 1 percent of French men,2 the new “Law of the Double Vote” empowered the richest quarter of that 1 percent with an even bigger say. This top 0.25 percent — who were disproportionately ultraroyalist — could vote as usual for the regular 258 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, but then also got to vote for a second set of 172 seats.3

Meanwhile, the government ordered state officials — especially the appointed “prefects” who ran each of France’s 86 departments, or provinces — to manipulate the vote further. I’ll talk more about some of these tactics later on, but for now note that all Restoration governments manipulated the vote but Villèle in 1824 brought things to a whole new level.4

As a result of all this, you’ll be unsurprised to learn that when all the votes were counted in 1824, candidates associated with the right and far-right won 416 deputies, against just 34 deputies for the left.5

The breaking of the fellowship

But this dominant position for the Ultras started to splinter, bit by bit, almost immediately. One group of far-right Ultras, called “the impatient ones,” frequently voted against Villèle because he wasn’t moving aggressively enough to enact Ultra priorities. “Here is a man who finds no one royalist enough,” an exasperated prefect complained about one of these “impatient ones.”6

But this dominant position for the Ultras started to splinter, bit by bit, almost immediately. One group of far-right Ultras, called “the impatient ones,” frequently voted against Villèle because he wasn’t moving aggressively enough to enact Ultra priorities. “Here is a man who finds no one royalist enough,” an exasperated prefect complained about one of these “impatient ones.”6

Above left: Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, “Chateaubriand Meditating on the Ruins of Rome.” After 1808. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below left: Thomas Lawrence, “Charles X, King of France,” 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Another group of Ultras split off later in 1824, when King Louis XVIII and Villèle fired France’s foreign minister, the famous writer François-René de Chateaubriand. Offended, Chateaubriand went straight into the opposition, bringing his acolytes and his brilliant pen with him.7 This faction is perhaps best situated as being on the center-right of 1820s Restoration politics; Villèle was hemorrhaging support from both flanks of his coalition.8

As a shorthand, some contemporaries referred to liberals in this period as the “opposition” and the dissident Ultras as the “counter-opposition,” which is just a delightful term to refer to politicians who oppose a government of their own faction for not being radical or pure enough.

Not too long after this, King Louis XVIII died and his younger brother took the throne as King Charles X. Louis had a somewhat moderate reputation, but Charles was known for his ultraroyalist views, as I’ve covered throughout the podcast but especially in Episode 26. Charles enjoyed a bit of a honeymoon phase after taking the throne, but by the summer of 1825 his popularity had begun to wane.

Some of this decline in popularity was perhaps natural, as Charles’ novelty faded and he got down to governing. But a lot was related specifically to Charles’ actions and to his opponents’ attacks. In particular, I want to highlight a few key issues where Charles and Villèle drew attacks from the public.

Religion

The first and possibly most prominent issue was religion. As I covered in Episode 28, the Bourbon monarchy had a policy of providing moral and material support to the Catholic Church, which had some successes but also often provoked backlashes from the many secular French people in this post-Revolutionary country. Much of this backlash was localized when the king was Louis XVIII.9 But when the devoutly religious Charles took the throne, some people started seeing these local complaints as part of a national conspiracy. In particular, the year 1825 is widely recognized as having been a “critical turning point in the growing obsession with and fears of a clerical plot.”10

That only accelerated as Charles began rolling out his legislative agenda, which included a new law authorizing the formation of new religious orders, and a highly controversial “sacrilege law” that imposed the death penalty for profaning communion vessels.11 These ideas weren’t new, and Villèle’s government had brought them up in parliament in Louis’s final years, too. But they didn’t pass then. Charles put his prestige on the line and muscled them into law — a legislative victory, but one that associated him personally with the controversial new laws.

Charles’ critics kept finding new ammunition. In 1825, Charles held a formal coronation ceremony, where a bishop anointed him with sacred oil, and where he participated in a medieval ritual by touching suffers of a disease called “scrofula” in an attempt to cure them with his royal touch. In 1826, Charles participated in public celebrations of a papal Jubilee. This included one ceremony in honor of Charles’ guillotined brother Louis XVI, in which the king wore a velvet mourning cloak — the same deep purple color as the robes worn by the Catholic bishops. This started an unkillable conspiracy theory that Charles had been made a secret bishop. Though there is zero evidence this conspiracy theory was actually true, for critics, his “subservience to the Church seemed complete.”12

There’s a lot more to be said about the attacks on Charles as a religious extremist, including attacks on him for alleged ties to the Jesuit order and to a shadowy, half-mythical ultraroyalist secret society people called “The Congregation.” But there’s so much to say on that topic it will have to wait for another episode where I can give it its due. Suffice to say, Charles and Villèle faced mounting attacks on the issue of religion, even as many traditionalist Catholics were thrilled by the government’s championing of them.

Above: The consecration of King Charles X during his coronation ceremony, by François Gérard, 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Censorship

All these fights over religion played a key role in setting off the second major political controversy of 1827: press censorship. Opposition newspapers, and especially Le Constitutionnel, the biggest liberal paper, had hammering home anti-clerical themes for years, and Villèle had tried with increasing desperation to put a stop to it. I talked about some of these steps back in Episode 22, including an emergency censorship law passed in 1820, and a cloak-and-dagger scheme to secretly buy up opposition newspapers with government funds.

But these measures met with mixed success, and in December 1821, a coalition of liberals and Ultras joined forces to block a new law extending censorship.

The years that followed saw the French government — deprived of explicit censorship powers — try to use libel laws to keep control over the opposition press. In particular, Villèle used a law that made newspapers culpable if they showed a “general tendency… injurious to public peace or to the respect due to religion” — even if no individual article crossed the line.13

At first, this law proved very effective. A number of prosecutions were brought against newspapers throughout 1822 and 1823, and they were generally successful, with “convictions… secured for the most trivial offenses” and liberal journalists forced “to be extremely cautious to escape fines and imprisonment.”14

But as the political tides began to turn, opposition papers became bolder, and the government found it harder to secure convictions. The key showdown happened in 1825, when Le Constitutionnel amped up its longstanding campaign against the so-called “priestly party.” In May, June and July of that year alone, Le Constitutionnel published 34 different anti-clerical articles. Readers were told about all sorts of priestly outrages, many made up or exaggerated, often perpetrated by those sinister Jesuits. But the more Le Constitutionnel attacked the Church, the more its circulation grew, and the more smaller opposition newspapers hastened to join it.15

Finally Villèle’s government had had enough. In August 1825, they brought Le Constitutionnel and another paper16 up on charges of disparaging the Catholic Church. It defended itself by saying it had criticized not the Church as a whole but “unauthorized associations which were menacing the state” — that is, the Jesuits. The courts, which had once convicted newspapers so readily, acquitted Le Constitutionnel.17

With this legal weapon seeming to lose its effectiveness, Villèle asked the Chambers for a new censorship law, which soon acquired an unfortunate nickname. Critics had accused the bill of being “arbitrary” or even “a measure of hate,” but the Minister of Justice insisted that those attacks couldn’t be more wrong. In truth, the minister said, the censorship bill was “a law of justice and love” — a label the opposition immediately co-opted ironically.18

Supporters said censorship was either necessary, to constrain press “abuses,” or even a positive good. One such statement came from Louis de Bonald, an ultra-royalist philosopher and Peer who was Charles’ choice to oversee the new censorship office. Bonald called censorship “a sanitary institution established to preserve society from the contagion of false doctrines” and said that with such a restricted electorate France really had no need of a “political press” at all.19

Many Frenchmen vehemently disagreed. Petitions opposing the law poured in to the Chambers from critics big and small. Print-shop workers faced the loss of their livelihoods. So did newspaper owners; it was said the effect of the bill would be to subsidize printing presses across the border in Belgium. Chateaubriand called it a “vandal law” and even the normally subservient French Academy voted a protest.20

But while the Ultra-controlled Chamber of Deputies approved the law, it ran into resistance in the Chamber of Peers, where liberal peers like the Duc de Broglie used parliamentary procedures to systematically tear the “Law of Justice and Love” to shreds in early 1827. The government withdrew the bill. In the streets, jubilant crowds chanted “Long live the king, long live the Peers, down with the ministers.”21

But while the Ultra-controlled Chamber of Deputies approved the law, it ran into resistance in the Chamber of Peers, where liberal peers like the Duc de Broglie used parliamentary procedures to systematically tear the “Law of Justice and Love” to shreds in early 1827. The government withdrew the bill. In the streets, jubilant crowds chanted “Long live the king, long live the Peers, down with the ministers.”21

Right: Victor de Broglie, Duc de Broglie, engraving by Antoine Maurin and Nicolas Eustache Maurin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This was just a temporary setback for Villèle, however. While the Peers had blocked a permanent censorship law, existing laws did permit the government to impose temporary censorship by royal ordinance in between sessions of the Chambers. Louis XVIII had done this near the end of his reign, but — as I mentioned in Episode 28 — Charles lifted censorship as a goodwill gesture at the start of his reign. By 1827, however, Charles had changed his mind after seeing the onslaught from the opposition papers. He somewhat reluctantly agreed with Villèle that it was time for another round of censorship. On June 24, 1827, Charles issued a royal ordinance that once again required newspapers to submit their articles to censors for approval prior to publication.22

I’ll talk more about the impact of this temporary censorship in a bit. For now, the important thing is to note that in the summer and fall of 1827, lots of French people were extremely ticked off with Villèle over newspaper censorship.

Greece

Then there was the Greek War of Independence. I covered this in depth in Episode 30, but in short, the Greek struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire became increasingly popular in France starting in the mid-1820s.

Villèle’s government was trying to hold to a formally pro-Ottoman foreign policy, and had an extremely close relationship with Muhammad Ali, the powerful modernizing ruler of Egypt who was helping to suppress the Greek rebellion. The logic made a certain sense: how could the Restoration government logically claim to oppose revolution at home while supporting it abroad?

But this cold logic was out of step with the philhellenic fervor that was taking over French high society. Villèle got no credit for turning a blind eye to individual Frenchmen who wanted to help the Greeks. Every setback the Greek rebels suffered was blamed on the failure of Villèle’s government to aid them. He was increasingly taking fire over the issue from both liberals and Ultras, especially the omnipresent Chateaubriand.23

By 1827, Villèle had bent under these headwinds. France signed a July 1827 agreement with Britain and Russia to send fleets to Greece to try to force an end to the hostilities. We will hear more of this fleet by the end of this episode, but for now just know that dispatching a peacekeeping fleet had done little to win over Villèle’s critics.

It’s the economy, stupid

There was also one non-political development that helped shape the 1827 campaign. In modern terms, France in 1827 was in the middle of a significant economic recession.

The story of this recession starts several years prior, and has little to do with France. Back in 1822, Britain lowered the interest rate it paid on government bonds from 5 percent to 4 percent, followed by a half-percent cut two years later. With domestic bonds suddenly less lucrative, British investors rushed to invest in foreign bonds, especially for the revolutionary new nations of South America. This overseas debt regularly paid 5 to 8 percent and could often be purchased at a discount. British money poured in.24

The bubble eventually burst in what we now call the “Panic of 1825,” as South American investments started to default, prompting a full-blown financial crisis and a series of bank runs.25 The contagion quickly spread to the rest of Europe. The journalist Adolphe Thiers wrote in 1826 how “The English, who had by their considerable purchases given great impetus to our manufactures, suddenly withdrew. Thus all Normandy, Picardy and Flanders were dropped into dreadful suffering… Everywhere there were the cries of unemployment.”26 Charles announced a public works spending program in early 1827, hiring the unemployed to build highways and fortifications,27 but it didn’t appear to make a difference. French bankruptcies rose by two-thirds in 1826 and remained high in 1827, while the stock market declined. These unemployed workers couldn’t vote, but their bosses could; as historian David Pinkney summarized it, “investors and businessmen… grumbled and read the opposition newspapers.”28 This had a knock-on effect, too: Villèle held the office of Finance Minister and had a reputation as a financial wizard. So when the recession started to harm the French budget, some people started to wonder whether Villèle was really as necessary as they had once thought.29

Even in today’s data-rich world, it can be hard to disentangle the roles that structural factors vs. hot-button issues play in deciding elections. So I’m certainly not going to be able to tell you whether the bad economy was more important for the 1827 election than concern over religious issues. But I think we all know enough to not discount the power of a recession to take the shine off a once-popular government.

Unpopular, or merely less popular?

Now, don’t let my rundown of these controversies create the impression that everyone hated Villèle. Lots of France’s small, elite electorate was still on board with this ultraroyalist government, which could tout some genuine accomplishments. Others may not have been ideologically on board with Villèle, but were financially dependent on his favor for government jobs or handouts. One critic quipped in his journal that “M. de Villèle has just as many supporters as the plague would have if it distributed pensions.”30

That quote is funny, if not quite fair. As the Election of 1827 loomed, no one thought Villèle’s government was doomed. But the political climate had changed since 1824, and not in Villèle and Charles’s favor.

One vivid example of their faded standing came on April 29, 1827, when Charles attended a review of the Paris National Guard. While the king received plenty of cheers, a minority of guardsmen heckled him with chants like “Down with the Ministers!” and “Down with the Jesuits!” When one bold soldier stepped out of rank to heckle Charles to his face, the king angrily retorted, “I came here to receive homage and not lectures.” Another legion jeered Villèle while marching past his offices. The heckling actually wasn’t as bad as Charles had feared, but Villèle persuaded him that the insults required a harsh response. That night, Charles summarily disbanded the entire Paris National Guard.31

You might want to keep this incident in the back of your minds for future episodes.

Why 1827?

So now you have a pretty good idea of where French politics stood in mid-1827. But it’s not immediately obvious why this should matter. Charles was a powerful king backed by a huge ultra-royalist majority in the Chamber of Deputies. And those ultra-royalist deputies had been elected in 1824 to a five-year term.32 You can do the math — the Chamber still had several more years to sit.

And yet the title of this episode is “The Election of 1827.” King Charles is going to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies in 1827 and call for new elections that fall. Why did he get rid of his own majority?

The key thing is to remember that France’s parliament had two chambers. And the Chamber of Peers had proven a repeated stumbling block for ultraroyalist measures. We just saw how the Peers had gutted Villèle’s censorship bill in 1827. Well, that was far from the first time the Peers had proven a nuisance. Back in 1824, Louis XVIII tried to compensate émigrés for their confiscated land. This passed the Chamber of Deputies, but was rejected by the Peers. The same thing happened to an 1824 law governing religious orders.33 In 1825 Charles used his influence to secure passage of the “émigré’s billion” and the blasphemy bill, but this proved a temporary respite. In 1826 the Peers killed a bill changing inheritance law to help wealthy families keep their estates together.34

Below: Paolo Toschi, “Élie Decazes,” circa 1813. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

So why was the chamber of appointed aristocrats more hostile to Charles than the elected chamber? To understand this, we need to go back nearly a decade to the year 1819, and a showdown I covered back in Episode 14. In that year, the Chamber of Peers was dominated by royalists who frustrated the agenda of Louis’ relatively liberal prime minister, Élie Decazes. To break this deadlock, Decazes persuaded Louis XVIII to use his royal prerogatives to appoint more than 50 liberals to the Chamber of Peers.35 This solved the 1819 political crisis — but because Peers served for life, most of these men were still around in 1827 to take liberal positions, even though the monarchy by now was in the ultra-royalist camp.

So why was the chamber of appointed aristocrats more hostile to Charles than the elected chamber? To understand this, we need to go back nearly a decade to the year 1819, and a showdown I covered back in Episode 14. In that year, the Chamber of Peers was dominated by royalists who frustrated the agenda of Louis’ relatively liberal prime minister, Élie Decazes. To break this deadlock, Decazes persuaded Louis XVIII to use his royal prerogatives to appoint more than 50 liberals to the Chamber of Peers.35 This solved the 1819 political crisis — but because Peers served for life, most of these men were still around in 1827 to take liberal positions, even though the monarchy by now was in the ultra-royalist camp.

You might wonder why Charles didn’t simply repeat Decazes’s gambit and appoint a bunch of Ultras to the Peers. Well, that’s exactly what he wanted to do! But Charles had a problem. Most of the eligible candidates — reliably Ultra noblemen who weren’t already Peers — were members of the Chamber of Deputies.36 So appointing the extra Peers that Charles needed would come at the expense of his tenuous majority of Deputies.

This itself didn’t require a new general election. Charles could appoint a bunch of Ultra Deputies to the Peers, and then let those seats be filled by one-off special elections, also called by-elections. But as any modern-day politics-watcher can tell you, special elections can be unpredictable. And recent trends gave Villèle and Charles good reason to not rely on special elections.

There had been six by-elections in the past 15 months, and five of those six elections had been won by opponents of Villèle’s government. One, most alarmingly, had been won by that unreconstructed revolutionary, the Marquis de Lafayette, who had returned tanned, rested and rejuvenated after his American tour that we covered in Episode 24.37

More generally, there was a sense that the political climate was turning against Charles. Remember the National Guard incident? Charles had clearly become less popular since assuming the throne in 1824. But maybe he was going to continue to lose popularity. If that was the case, then maybe better to hold an election now — at a time of Villèle’s choosing — than take a chance with the political climate a few years down the road.38

So to recap: Charles and Villèle needed to appoint new Ultras to the Chamber of Peers in order to get their agenda passed. To do that, they needed to pluck men out of the Chamber of Deputies. To replace those Deputies, they needed to hold elections. And they thought a nationalized general election would be more promising than a bunch of local by-elections.

Were they right? Let’s see how this all played out.

Rural jurors

The battleground for what would become the Election of 1827 was shaped by an unlikely law that passed the Chambers earlier that year: jury reform.

I know, I know. But stick with me here. This is important. In Restoration France, eligibility for juries was tightly linked to eligibility to vote. And what began as a bill tweaking juries ended up as a law reshaping the 1827 electorate.

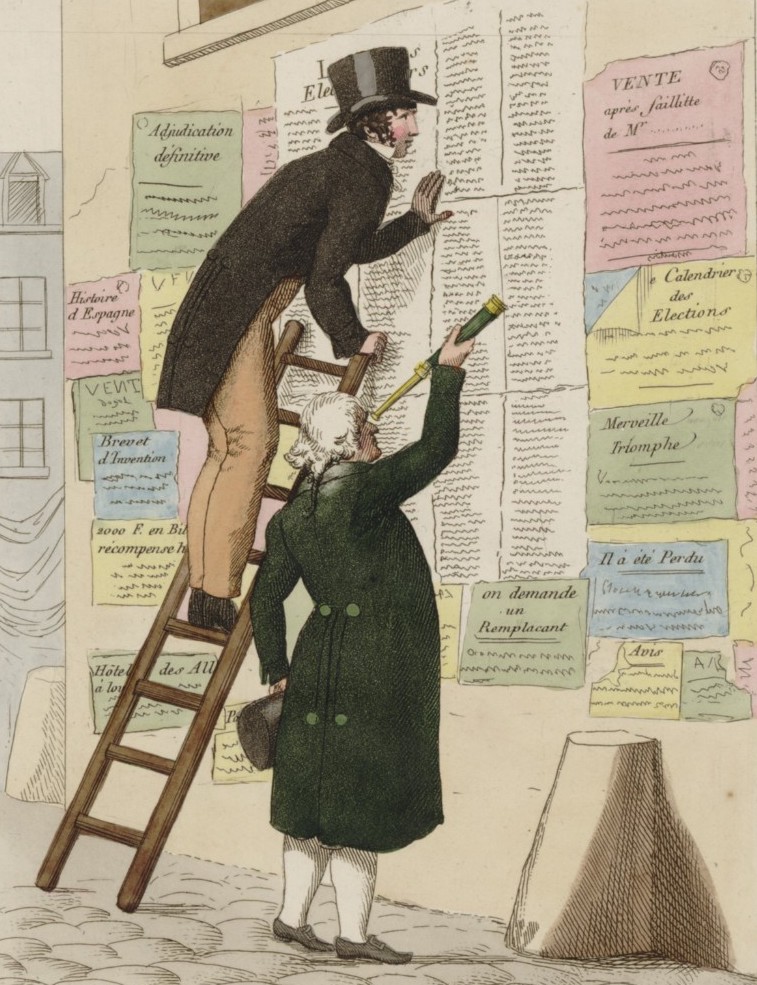

Right: Unknown artist, “Two men search for their names on a list of eligible voters,” 1817. Public domain via the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Let’s dig in. I talked earlier about how Restoration prefects meddled in elections to boost pro-government candidates. One of the ways they did that was through their power to draw up the lists of eligible voters in their department — that is, which residents paid at least 300 francs per year in direct taxes. Prefects would regularly forget to add known liberals to the electoral lists. On the other side, the strict standards by which they judged whether liberals were rich enough to vote were quite a bit looser when it came to known royalists. For example, the prefect of the Vosges on one occasion added 91 royalist electors who were technically under the 300-franc threshold, as well as a few royalist electors with the minor impediment of being dead.39

Eligible voters who were omitted from the voter rolls had the right to appeal, of course, and prefects would often back down when presented with actual evidence. But to minimize these inconvenient appeals, prefects would post the electoral list as late as possible, with little notice, and often in inconvenient places, such as so high on a wall that it couldn’t be read without a ladder.40

This is the process that the 1827 jury reform law ended up tackling — at least, once the liberals in the Chamber of Peers got through amending it. No longer could prefects post a single voter list in some out-of-the-way place; now they had to post a copy in every single community in their department.41 Instead of prefects publishing voter lists at the last minute, the new law created a standardized process by which jury lists — that is, future electoral lists — had to be published by August 15 each year, with a fixed six-week period given for appeals. And disqualified voters were given the right to appeal their disqualification to the courts if the prefect rejected them.42

The result of this so-called jury bill was to curtail the government’s use of electoral skullduggery, and to create a clear process by which opposition voters could make sure they were allowed to vote.

That doesn’t mean navigating that process would be easy, though. Villèle’s prefects still had plenty of dirty tricks to reshape the electorate. And opposition newspapers were muzzled by the temporary censorship, which took a sudden and dramatic effect.

Politics suddenly vanished almost completely from opposition newspapers starting in late June 1827. And this doesn’t just mean openly partisan attacks. On July 23, for example, the censors barred Le Constitutionnel from printing an article predicting — accurately! — that the government would dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and call an election.43

But the passage of the jury law gave all these censored journalists something else to write about.

God helps those who help themselves

Charles didn’t formally announce that he would dissolve the Chamber of Deputies until November. But the possibility had been an open secret among the French political class for months. Back in July, Chateaubriand had published a pamphlet ostensibly devoted to attacking the recently imposed censorship. But after discussing the details of censorship for a few pages, Chateaubriand pivoted to explicitly political terms: “Realize that no one will come to your home to alert you to your opportunity to be inscribed as a voter; surely the authorities will not, and the press under the yoke of the censorship will have to keep still. The first of October will arrive, and if the Chamber of Deputies is dissolved what will you do?”44

This pamphlet wasn’t just a one-off event. Its anti-censorship title was buried under a giant header: “Friends of the Liberty of the Press.” And already by that time, Chateaubriand had taken steps to form an organization by that name, a sort of 19th Century political action committee aimed at ending censorship by defeating the Villèle government that had imposed it.45

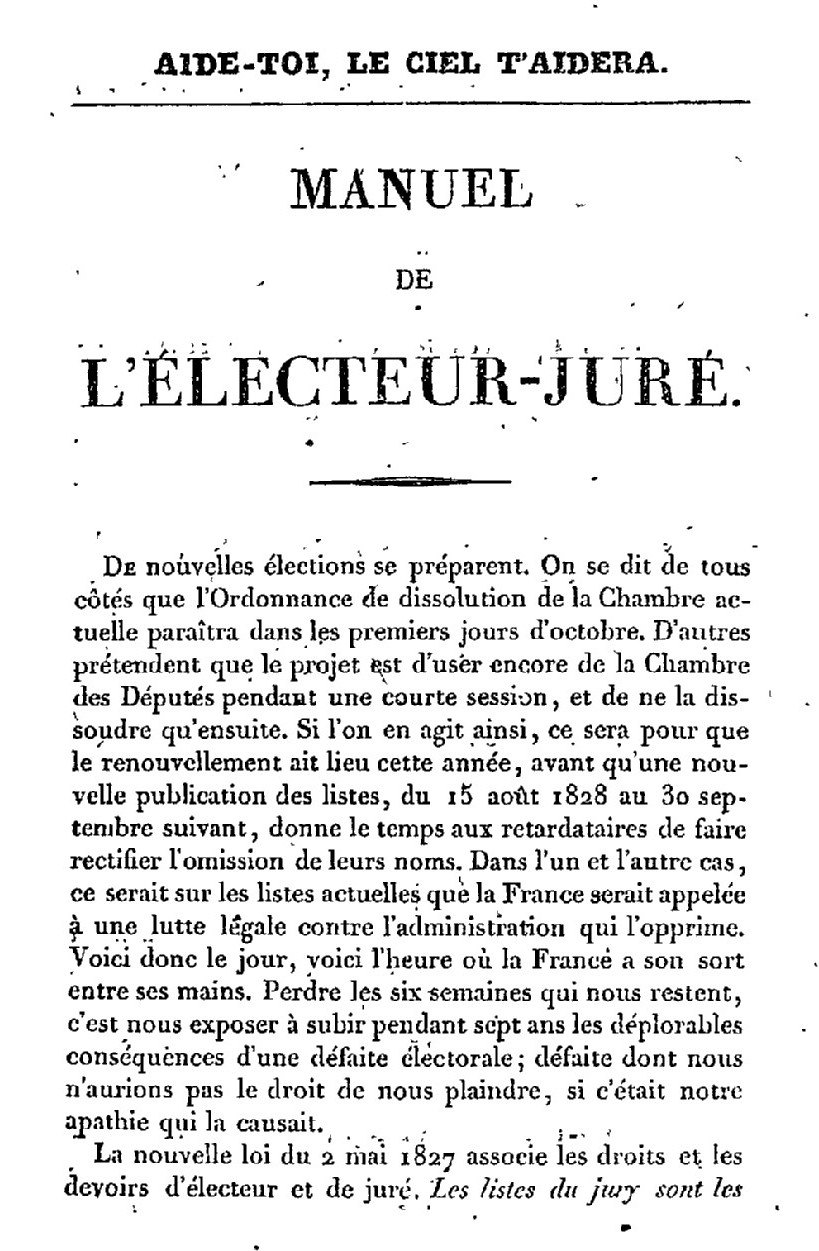

The Friends of the Liberty of the Press were joined about a month later by a similar group led by François Guizot, the liberal writer we met in Episode 29. Guizot’s group had a distinctive name that translates awkwardly into English; I’ll refer to it as the “Aide-Toi Society,” which is French for “Help Yourself.” That’s a shortening of the group’s full name, literally the “Help Yourself, and Heaven Will Help You Society,” or more elegantly the “God Helps Those Who Help Themselves Society.”46

The Friends of the Liberty of the Press were joined about a month later by a similar group led by François Guizot, the liberal writer we met in Episode 29. Guizot’s group had a distinctive name that translates awkwardly into English; I’ll refer to it as the “Aide-Toi Society,” which is French for “Help Yourself.” That’s a shortening of the group’s full name, literally the “Help Yourself, and Heaven Will Help You Society,” or more elegantly the “God Helps Those Who Help Themselves Society.”46

Right: François de Guizot, circa 1837, by Jehan Georges Vibert after Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Friends of the Liberty of the Press had their base in the conservative counter-opposition, while the Aide-Toi group was run primarily by liberal journalists. Despite these differences, both were on the same page tactically and urged a common front between the left- and right-wing opposition groups. An early sample of that kind of cooperation came from the most recent by-election, in the Charente department. The first round of voting had a liberal candidate and a ministerial candidate neck-and-neck, but both under the 50 percent threshold needed to win. So the liberal candidate withdrew and urged his voters to back the third candidate in the race: an anti-Villèle Ultra, who promptly triumphed.47

To get this message out, the Aide-Toi Society and the Friends of the Liberty of the Press both churned out pamphlets with a very practical purpose: explaining how prospective voters could make sure they were registered — and file a challenge if they were omitted.

You might be wondering how all these pamphlets are getting published, given the vigorous censorship I talked just talked about. Well, that’s because the censorship in the Bourbon Restoration was focused on regularly published newspapers. Books and irregularly published pamphlets weren’t covered by the requirements to pre-submit content for approval, though they were of course still subject to libel laws.48 And despite the censorship, newspapers could get away with publishing strictly neutral voter guides — even if everyone knew that the only people who needed voter guides were people who leaned toward the opposition.49

Many of these pamphlets didn’t have to worry about libel laws. While there were certainly elements of political polemic in these documents, the primary focus was strictly practical. Take, for example, the Aide-Toi group’s “Elector-Juror’s Handbook,” published in mid-August 1827 in separate editions addressed to the voters of each department. After an introduction, the pamphlet laid out in meticulous detail the various requirements to vote, the documentation a would-be voter needed to prove their eligibility, and instructions on where and how they needed to file them.50

Many of these pamphlets didn’t have to worry about libel laws. While there were certainly elements of political polemic in these documents, the primary focus was strictly practical. Take, for example, the Aide-Toi group’s “Elector-Juror’s Handbook,” published in mid-August 1827 in separate editions addressed to the voters of each department. After an introduction, the pamphlet laid out in meticulous detail the various requirements to vote, the documentation a would-be voter needed to prove their eligibility, and instructions on where and how they needed to file them.50

Left: The first page of one of the Aide-Toi group’s 1827 “Elector-Juror’s Handbook,” providing guidance to any would-be voter (but in practice mostly opposition voters) on how to get formally registered despite prefectoral resistance. Public domain via the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

If that sounds like a lot, remember that the audience wasn’t merely — or even primarily — the voters themselves. They were also addressed to France’s multitude of young lawyers, who swung into action to help other liberals get registered. Soon prefects began reporting the results of this campaigning with alarm, such as this report filed on August 30 by a prefect in the small, overwhelmingly rural department of Creuse:51

In line with suggestions in [opposition pamphlets] … young lawyers have formed consulting committees in the chief town of each district. There the electoral lists are scrutinized and I have been warned that a few days hence I will receive a great number of protests against the inscription of men who in the event of an election would support candidates of the government. I hear that [one of] these committees has decided that [its] young men will begin in mid-September to visit liberal voters in the countryside to urge them to gather the documents which will assure their inscription on the electoral lists.

These sort of reports came from across the country, along with worried reports about how many opposition pamphlets were being distributed, and the methods by which these dissidents were funding and distributing their campaign literature.52

I could go on about the specific ways that these two opposition campaigns worked to mobilize voters, but I think a simple statistic sums it up in two sentences: on August 15, French prefects announced that France contained around 70,000 eligible voters. When the appeal period ended six weeks later, they counted 88,000 voters — a 25 percent increase.53

By any standards, this early form of voter registration drive had been a smashing success. But would it translate into electoral wins? Remember, the last election had been an overwhelming landslide for the Ultras; they could afford to see some new opposition voters get registered.

Charles and Villèle received mixed signals as to the true mood of the country. Throughout August and September, they received gloomy reports from prefects along the lines of the one we just heard. There was also a concerning incident in late August, when the famed liberal politician Jacques-Antoine Manuel54 died and his funeral, predictably, turned political. A huge crowd turned out to join the procession, including dignitaries like Lafayette and the banker-politician Jacques Laffitte, but the procession devolved into chaos when police tried to intervene. On the other hand, when Charles left Paris for a tour of the northeast in September, he met enthusiastic crowds that reassured him. “Everything continues in a most agreeable and brilliant manner,” Charles wrote from the trip. The king’s widowed daughter-in-law, the Duchesse de Berry, was with him and wrote that his reception convinced Charles that “the agitations were only clouds that a favorable wind would soon blow away.”55

“The enemy redoubles his efforts,” Charles wrote to Villèle. “However, I am resolved to act with firmness and wisdom and am entirely confident that in the end we will overcome all obstacles.”56

Was he right? Let’s get to the campaign.

The campaign

King Charles X published his official decree dissolving the Chamber of Deputies on Nov. 6, 1827. This was paired with the appointment of 76 new members to the Chamber of Peers, 40 of whom were sitting deputies. He also — as the law required — lifted the temporary censorship he had imposed back in June.57

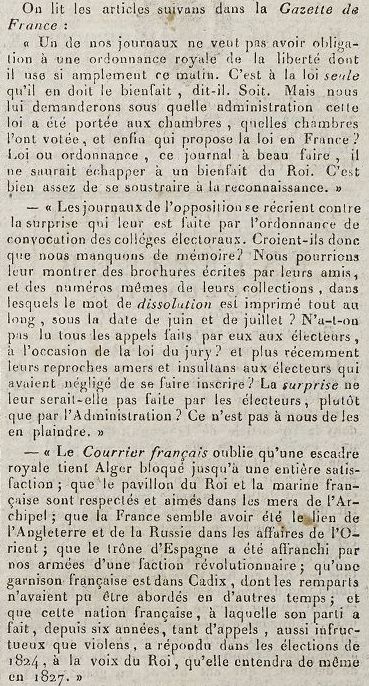

The opposition newspapers had their muzzles lifted at last — but they didn’t have much time. Between the lifting of the censorship and the initial voting there were only about 10 days. They didn’t waste any time, publishing lists of endorsed candidates the next day along with a host of various attacks and appeals, while the Moniteur responded with “fact-checks” of supposedly false opposition attacks.58

Villèle’s government was attacked for censorship and clerical influence, for corruption and tyranny. Charles himself was subjected to that old trope that “the good king was subject to bad influences.”59

Villèle’s government was attacked for censorship and clerical influence, for corruption and tyranny. Charles himself was subjected to that old trope that “the good king was subject to bad influences.”59

In response, pro-ministry sources emphasized Charles’ personal desire to see pro-government candidates re-elected, and implied that supporting the opposition was disloyal, faintly treasonous, or worse — revolutionary. “The hour has struck,” a royalist paper warned. “Men of good will, listen. The dike is open, and a tidal wave threatens us. Man the pumps and save society.”60

Right: Excerpt from the Nov. 8, 1827 edition of Le Moniteur universel, in which the government-run newspaper rebuts campaign arguments made by opposition newspapers and defends the record of the Villèle government. Public domain via DigiNole.

The Moniteur on Nov. 8 spent most of its front page responding to various opposition newspapers. These journals, the Moniteur said, overlooked the real accomplishments of Villèle’s ministry, especially in foreign policy: the successful intervention in Spain, a successful naval war with the ruler of the North African state of Algiers, and a diplomatic accord with Britain and Russia to intervene in Greece. The opposition in recent years had been “as fruitless as they are violent,” and voters would reject them in 1827 the same way they had in 1824.61

Professionals talk logistics

While journalists slung ink at each other, Villèle’s prefects got up to their usual tricks to bring out the pro-government vote. Government employees and active-duty soldiers, for example, were made to understand they were expected to support Villèle with their votes, and were given leave to make sure they were able to cast their votes unimpeded.62 Meanwhile Catholic bishops circulated prayers that governmental candidates would fare well in the elections.63

Prefects also made it as easy as possible for voters who weren’t already state employees to vote — as long as they supported the government, of course. State funds paid for voters’ lodging and transportation to the towns where the electoral colleges would meet, often for multiple days. Opposition voters had no such favors and had to scramble to arrange logistics — a deliberate government tactic to try to discourage attendance by the opposition. One prominent liberal wrote how he arrived at the tiny town chosen for the electoral college, which was “full to bursting”; in response a local ally had converted his home into a makeshift dormitory for more than 20 voters. “We slept badly,” he recalled.64

These campaign expenses added up to real money, though perhaps less than one might expect: around 264,000 francs. That is real money. But by comparison, when King Charles went on his month-long trip to northeastern France earlier that fall, he was given a budget of 220,000 francs alone for expenses and gifts.65 Some prefects burned through their entire election budgets and tried to get more money. Others ended up returning un-spent funds. Then there was the poor prefect of remote Corsica, who came to Paris two months after the election for a meeting and discovered to his shock that he was the only prefect who hadn’t been given access to the electoral slush fund. He swiftly filed for 1,500 francs of reimbursement for election expenses he had paid out of his own pocket.66

Against all this, opposition voters did their best to organize. The opposition didn’t have access to taxpayer money, but were hardly poor. The Aide-Toi Society was funded by a host of benefactors, including liberal bankers and industrialists, while a host of wealthy aristocrats in Chateaubriand’s circle did the same for the Friends of the Liberty of the Press. Opposition big-wigs also did speaking tours to fire up their voters, including Lafayette, Benjamin Constant, and Jacques Lafitte.67

Opposition voters also met for informal pre-vote caucuses where they agreed on tactics. This was essential because elections in the Restoration weren’t like today’s mass elections, with thousands of voters showing up and dropping a ballot in a box. They were more like today’s party caucuses or conventions — an in-person meeting lasting hours or days, with speeches and multiple rounds of voting until each electoral college had picked its allotted slate of winners.68 And getting together to coordinate a strategy was really important, given that the opposition voters included everyone from crypto-Jacobins to the “irons, executioners and torture” faction of extreme Ultras.69 Horse-trading was necessary to win.

The election

With mere days to go before voting, potentially sensational news arrived in France: the combined French, British and Russian fleet had won a smashing victory over the Ottomans and Egyptians at the Oct. 20 Battle of Navarino. With the slow speed of travel at the time, it wasn’t until early November that news reached France, but it did make it to France in time to impact the elections.70

But the military triumph doesn’t appear to have changed anything. The Moniteur claimed the victory had been “entirely French and entirely royalist,” but opposition papers had been beating the drum to aid the Greeks for years now and saw Navarino as a triumph for their cause, too.71

Instead, French voters would meet in their electoral colleges on Nov. 17 for an election whose contours had been shaped by months of campaigning, rather than by a November Surprise. In this era long before opinion polling, no one knew exactly what to expect. But experts on both sides had fairly similar expectations for the voting: that the opposition would have a good showing and eat further away at Villèle’s majority in the Chamber of Deputies.

For example, François Guizot predicted around 80 liberals and 40 to 50 deputies from the right-wing counter-opposition — or around 30 percent of the Chamber’s seats in total. The ministry was somewhat better-informed, due to confidential reports from prefects and other government officials; an election forecast assembled by some 19th Century Nate Silver in the Interior Ministry predicted 60 percent of the seats would go to royalists, against 25 percent to liberals and 15 percent to the counter-opposition — a 60-40 win for the “royalists.”72

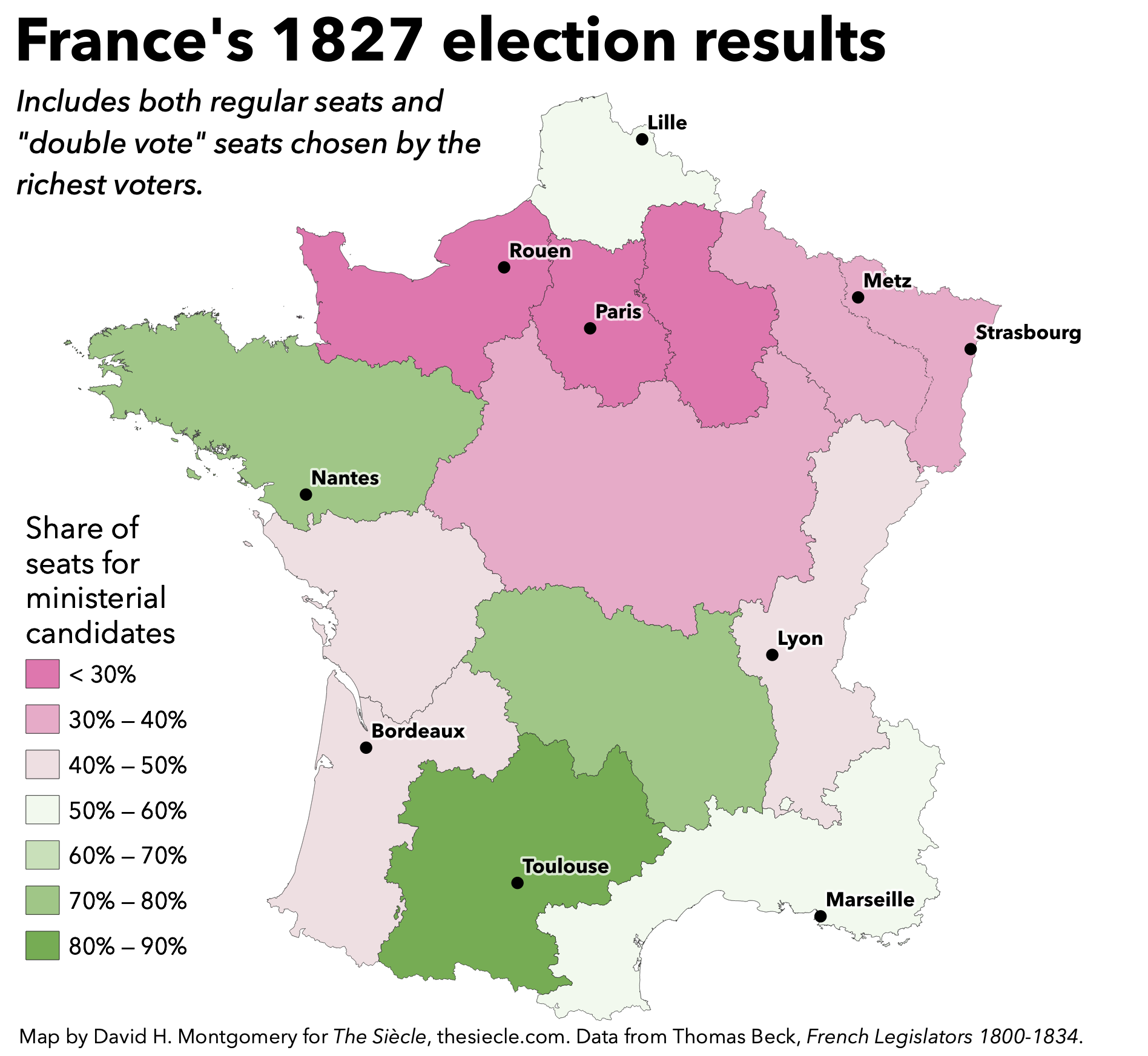

Instead, the opposition shocked everyone by winning outright. Party affiliations in those days were loose and every historian’s attempts to assign each deputy to a faction comes up with different numbers. To pick just one by way of example, historian Sherman Kent counted 195 pro-Villèle deputies, 199 opponents to Villèle’s left, and 31 opponents from the counter-opposition. (Another five deputies had unclear loyalties.) Despite the varying results: the big picture was pretty clear: a stunning rebuttal of Villèle, but a muddled Chamber where no one faction had a clear majority. In the “normal” elections held by the entire electorate, opposition candidates had won more than 60 percent of the roughly 258 available seats. Perhaps even more impressively, they even won 40 percent of the roughly 172 “double vote” seats chosen only by the wealthiest quarter of voters.73

The result was a dilemma for the still-young Restoration political system. It wasn’t entirely clear to whom a government minister was ultimately responsible. Was it the king, or parliament? And if the government was responsible to “parliament” in general, what happened when the Chamber of Peers and Chamber of Deputies had different majorities?

In November 1827, Villèle and the rest of the French political elite were forced to grapple with one specific question in particular: could the king appoint a prime minister who couldn’t command a majority in the elected Chamber of Deputies? Though none of this was written down in the Charter, an unwritten understanding was very slowly forming that ministers needed to have support from the Deputies.

But this unwritten understanding was far from consensus. Charles liked Villèle and didn’t want see him go. To stay on, though, Villèle needed to find a way to cobble together some sort of coalition. And he tried, multiple times. Ultimately, though, it came to nothing. Villèle had made too many enemies over the years, and many men who were approached to join a government said they would only do so if Villèle was gone. Eventually, very reluctantly, Villèle went into retirement. As was customary, he was given the golden parachute of an appointment to the Chamber of Peers on his way out, where he would sit alongside fellow former prime ministers Talleyrand and Élie Decazes.74

I’ll talk about the government that Charles appointed to replace Villèle in a future episode. Instead, I want to close by mentioning a minor but very significant event that happened as a consequence of the Election of 1827. Once it became clear that Villèle had suffered an electoral defeat, thousands of Parisians turned out into the streets to celebrate. There were parades and dances, and what were called “illuminations” — that is, people collectively putting lights in their windows at night in a gesture of solidarity. But some of these protests grew, uh, exuberant. Rocks were thrown through some un-illuminated windows. As the violence grew, rioters in a few areas tried to protect themselves from oncoming soldiers by building barricades in the street.75

This was not a revolution, and these barricades were swiftly demolished. Barricades had not featured in the great mob actions of the French Revolution, except for a brief cameo in 1795. They were novel and untested. But if there’s anything people know about 19th Century French history, it’s that this is not the last time we are going to see barricades in the streets of Paris.76

This is the part of the episode where I often thank people who support this show on Patreon. And indeed, I’m grateful to listeners Marleen, James Day, Mary Jean Andres, Magnús Pétursson, G.C., Chris Morris, Gruck Ta, Jonathan Parts, Damian and Kurt Gittler for joining more than 80 other supporters pledging as little as $1 per month.

But I wanted to do something a little different this time, and talk about the creators that I support on Patreon. Part of my pledge to supporters was that I’d pass on some of what they give me to other creators, and I’m currently backing five worthy writers and podcasters that you should check out if you haven’t already.

Some of them listeners are familiar with already. I back the Pax Britannica podcast by Sam Hume, who appeared on this show in Supplemental 5 to compare the 1820 assassination of the Duc de Berry with the 1628 killing of the English Duke of Buckingham. I also back The Age of Napoleon podcast by E.M. Rummage, who recorded the intro to Episode 11, and the Pontifacts podcast by Fry Cukjati and Bry Jensen — who recorded the cold open for Episode 27.

The other creators you should be familiar with. One is another French history podcaster, Diana Stegall of The Land of Desire. The other is a little different. History professor Bret Devereaux writes an amazing blog, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, with fascinating and fun deep dives into history and pop culture. You can visit thesiecle.com/episode31 for links to all five Patreons!

Now it’s back to the writing grind. Get your cork-boards together and prepare for a deep dive into the heady world of Restoration conspiracy theories. Join me next time for Episode 32: The Congregation.

-

See Episode 18. ↩

-

See Episode 15. ↩

-

Robert Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition: Liberal Opposition and the Fall of the Bourbon Monarchy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 144. ↩

-

See Episode 25. ↩

-

Sherman Kent, The Election of 1827 in France (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1975), 99. ↩

-

See Episode 25. ↩

-

Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition, 190. ↩

-

See Episode 27. ↩

-

Sheryl Kroen, Politics and Theater: The Crisis of Legitimacy in Restoration France, 1815-1830 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 216 ↩

-

See Episode 28. ↩

-

Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 226-7 ↩

-

Irene Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 1814-1881 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), 37. ↩

-

Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 38 ↩

-

Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 39-41 ↩

-

Besides Le Constitutionnel, another paper, Le Courier français, was also prosecuted at the same time. ↩

-

Geoffrey Cubitt, The Jesuit Myth: Conspiracy Theory and Politics in Nineteenth-Century France (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 68-70. Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 39-41 ↩

-

Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 50 ↩

-

Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 51. Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 387 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 15-16. ↩

-

Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 37. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 40-1. Charles was in general less supportive of censorship than Louis XVIII had been, and Villèle’s diary records that Charles was initially opposed to censorship before coming around. ↩

-

Mark Mazower, The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (New York: Penguin Press, 2021), 332, 335. Beach, Charles X of France, 233. ↩

-

William St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2008), 205-6 ↩

-

St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, 217 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 108-9 ↩

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 59 ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 391 ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 390 ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 389 ↩

-

There is some dispute, then and now, about how long the 1824 Chamber’s term was. When elected, it was for a five-year term, but the lawmakers subsequently passed a law extending deputies’ terms to seven years. Historian Sherman Kent notes that most people felt that new seven-year term applied to the sitting parliament, but that some people at the time had disagreed. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 33. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 115. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 384-8. ↩

-

Historian Philip Mansel gives the number of new peers as 68, while Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny and David Skuy give it as 59. See Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 362; De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 160-1; David Skuy, Assassination, Politics and Miracles: France and the Royalist Reaction of 1820 (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 45. ↩

-

Under the Charter of 1814, Peers had to be appointed by the King. Though Peers could be appointed at any age, they only could take possession of their seats at age 25 (compared to 40 for Deputies) and didn’t gain the right to participate in debates until age 30. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 36-7 ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 391-2. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 34. ↩

-

Pamela Pilbeam, “The Growth of Liberalism and the Crisis of the Bourbon Restoration,” The Historical Journal 25, no. 2 (1982), 360 ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 296 ↩

-

In fact, our archival evidence for Restoration voter lists mostly comes from this latter period, when they were printed and widely distributed; the paucity of surviving voter lists before this period suggests many of them were likely written out in longhand and never copied. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 30n53. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 27-8 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 42-3. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 81-2 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 82-5 ↩

-

The unusual name — Société, Aide-toi, le ciel t’aidera — was coined by the 24-year-old journalist Ludovic Vitet. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 89-90 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 45-6 ↩

-

Sylvia Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 1814-1824: Politics and Conspiracy in an Age of Reaction (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 68-9. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 43 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 91 ↩

-

Just 5 percent of the inhabitants of Creuse lived in towns circa 1820, the lowest percentage of any department. Historian Thomas Beck estimates the department had about 450 voters in 1817. Thomas D. Beck, French Legislators 1800-1834: A Study in Quantitative History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 154-5. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 86-7 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 59 ↩

-

Previously seen only in a footnote to Episode 18, getting expelled from the Chamber of Deputies for opposing the invasion of Spain in a way that could be read as an implicit threat to Louis XVIII. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 243-4. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 48-50 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 56, 58, 124. The actual final decision to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies was made on October 24, after a long flirtation with the idea. While Charles signed the ordinances on Nov. 5, they weren’t published in the Moniteur until Nov. 6. Le Moniteur universel, Nov. 6, 1827. Accessed via DigiNole: https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu:578324. ↩

-

See, for example, the Nov. 8, 1827 Moniteur ↩

-

Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition, 200. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 138-9. Beach, Charles X, 249. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, Nov. 8, 1827. Accessed via DigiNole: https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu:578439. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 138-9 ↩

-

Pilbeam, “The Growth of Liberalism and the Crisis of the Bourbon Restoration,” 364. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 152, 128 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 53, 152. Kent reports that Charles had requested a 120,000-franc budget for his trip, but Villèle had thought that too little and added an extra 100,000. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 153. Kent notes that the interior minister “might be pardoned if he did not reimburse” the Corsican prefect, for the Corsican voters had elected two opposition deputies. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 85n, 100 ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 125-6 ↩

-

A reference to the “impatient one” leader, the Count de la Bourdonnaye, who said that “irons, executioners and torture” was the only way to root out liberals and Jacobins. See Episode 25. ↩

-

The earliest report I found of Navarino in the Moniteur came on Thursday, Nov. 15, 1827, two days before the voting began, citing a report from a sailing captain that had been printed in another French newspaper. Whether news had reached all of France’s sprawling departments before the vote I don’t know, though the area around Paris was probably informed, as would have been the Mediterranean coast and perhaps the area in between the two. Le Moniteur universel, Nov. 15, 1827. Accessed via DigiNole: https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu:578597#page/20/mode/2up. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 419 ↩

-

Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition, 205. Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 56. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 161, 199. The total number of seats won in each category is somewhat imprecise, because of a few special exceptions, and also cases where the “winners” were unable to serve and their seats were filled in a subsequent by-election. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 250-1. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 392-3 ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 250. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 292 ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 22. ↩