Episode 4: The Paradox of Paris

This is The Siècle, Episode 4: the Paradox of Paris.

The fundamental paradox at the heart of 19th Century France is Paris. On the one hand, too many histories about France have simply been histories of Paris, neglecting the vast, diverse and predominantly rural country we toured in Episode 3 of The Siècle. On the other hand, Paris is massively, disproportionately important. It’s simultaneously true that Paris in 1815 represented a little over 2 percent of France’s population and was thus wildly atypical of the lived experience of 19th Century French citizens — and that the actions of that 2 percent could and did shape the fate of the whole country.

So what kind of Paris did Louis XVIII return to in 1815? It was not yet the famous “City of Lights” — Paris’s first gas lamps would not be installed for a few years, and as late as 1830 there will be a mere 63 in the entire city.1 Nor was it the city of sweeping boulevards and grand buildings you can tour today; much of that would be forged during Baron Haussmann’s famous midcentury renovation of Paris, about which much more, much later.

Instead, this is a considerably dingier metropolis, but still one capable of stirring poets’ hearts. It is a city where, as novelist Honoré de Balzac described it, “the atmosphere of the streets belches out cruel miasmas into stuffy back-kitchens where there is little air” — but also, as Balzac wrote just a paragraph later, “the crown of the world, a brain which perishes of genius and leads human civilization.”2

I should say at the outset here that the focus of this episode is to introduce the physical Paris of the Restoration. That involves some discussion, of course, of the people who live there and the types of lives they lead. But if you find that discussion too brief for your liking, don’t worry — I’m intentionally holding some of it back for future episodes that will explore the daily lives of French people of all types in the first half of the 19th Century.

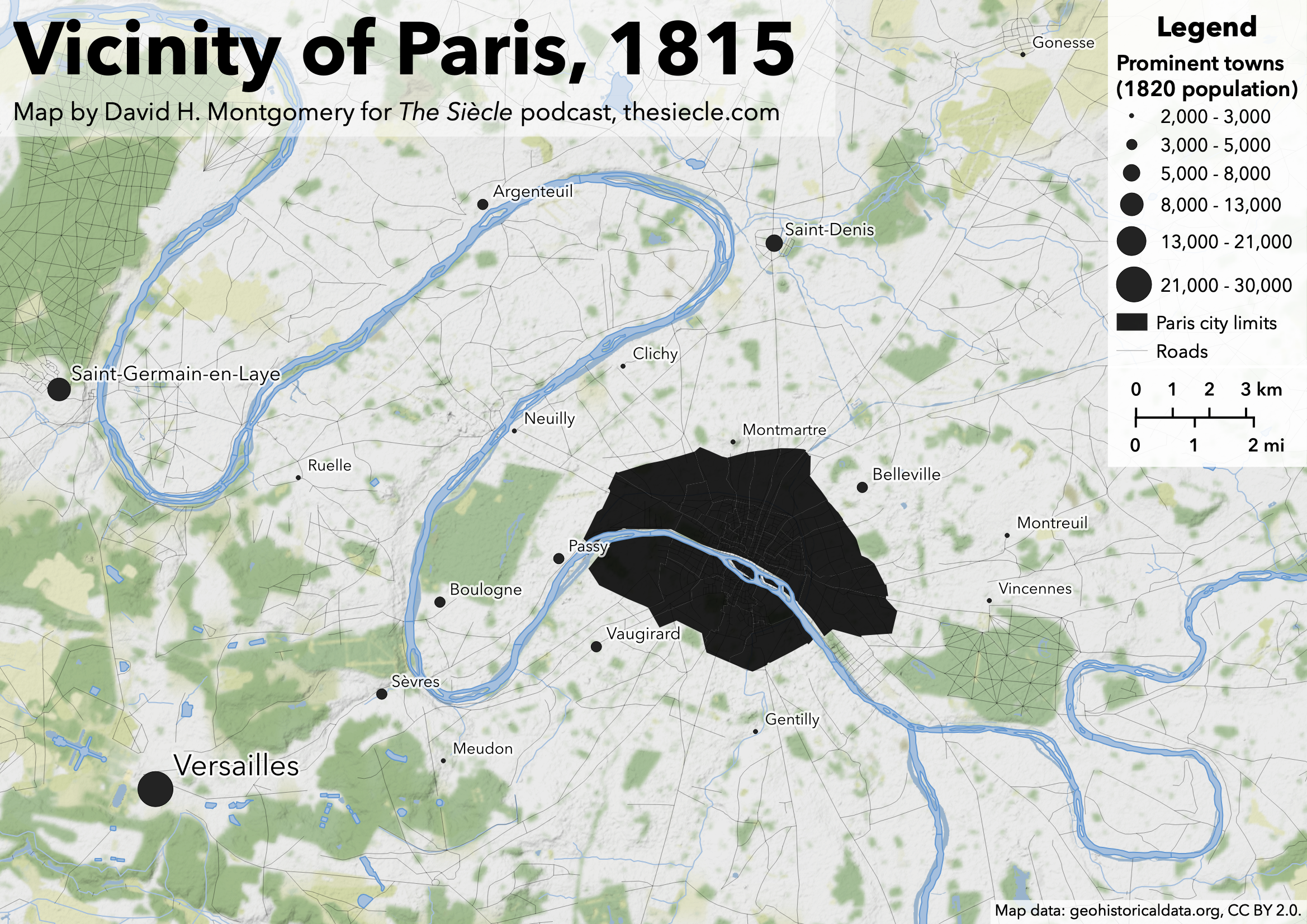

This paradoxical Paris from which Louis would rule had just over 700,000 residents in 1815, contained inside a 15-mile or 24-kilometer circumference border — an enclosed area one-third the size of the 21st Century Paris. At thesiecle.com/episode4, you can see a map I made overlaying 1815 Paris on the massively larger present-day metropolitan area, borders that exclude such famous Parisian landmarks as the Père Lachaise cemetery, the hill of Montmartre, and the Arc de Triomphe.

Instead, as you approached the city through what are today dense urban neighborhoods, in 1815 you’d pass through one or more suburban towns, which in the 21st century are merely neighborhoods of Paris. Back then, towns like Montmartre to the north, Belleville to the northeast, Vincennes to the east, Ivry to the southeast, Vaugirard to the southwest, and Neuilly to the west were distinct communities outside the Parisian border. Also just outside the border are two forests: the Bois de Vincennes to the southeast and the Bois de Boulogne to the west. These former royal hunting preserves had now been opened to the public, but are not quite the city parks they are today.

In addition to forests and suburbs around Paris, you’d also find plenty of farmland, running right up to Paris’s borders, and even some inside them! These suburban market-gardeners of the Paris region grew food to feed the city, and in 1815 you might see some of these farmers trudging into the city in the early morning, carrying their produce on their backs to deliver it to stores or markets within walking distance. Heading back the other way is Paris’s “night soil,” or poop, which fertilized these suburban fields and enabled them to produce as many as five or six harvests per year.3 And Paris needs all those harvests — the city consumes nearly 500,000 pounds of flour each and every day, hauled into town daily in giant, 325-pound sacks. On an annual basis, Paris also consumed 24 million gallons of wine, 76,000 cows, 363,000 sheep and 3 million pounds of cheese.4 Without railroads or refrigeration, all that food has to come from nearby.

But neither we nor the suburban farmers could just walk right into the city. In 1815, Paris is still surrounded by a wall. This isn’t a medieval wall, with towers and parapets, but neither is it a modern bastion to fend off cannonballs. Rather, this is a customs barrier, built just before the Revolution and dotted with 52 toll-houses at which visitors to Paris had to pay a tax on any goods they were carrying before they could enter the city. For example, a hectolitre of wine — about 26 gallons — would face a tax of just over 8 francs at the gates of Paris. That same hectolitre would sell for about 30 francs in the city, meaning this was about a 30 percent tax! Other goods were cheaper: cheese shippers had to pay a tax of around 1 percent of its average price in Paris, or around 11 francs for 100 kilograms of cheese that sold for more than 1,000 francs in the city. A bull or ox intended for the slaughterhouse would pay 19.8 francs, 6 percent of the typical 320-franc sale price.5

Once we get past the suburbs and the customs wall, we’d enter Paris proper, a city of stark contrasts. Foreign visitors, historians tell us, were astonished at how Paris’s palaces and monuments were in close proximity to shacks and slums, how its streets were a mixture of broad boulevards and unpaved medieval streets with open sewers running down their center.6

Arrondissements of 1815 Paris

Map of the old arrondissements of Paris and their quartiers, by Starus. CC BY-SA 3.0, via Creative Commons.

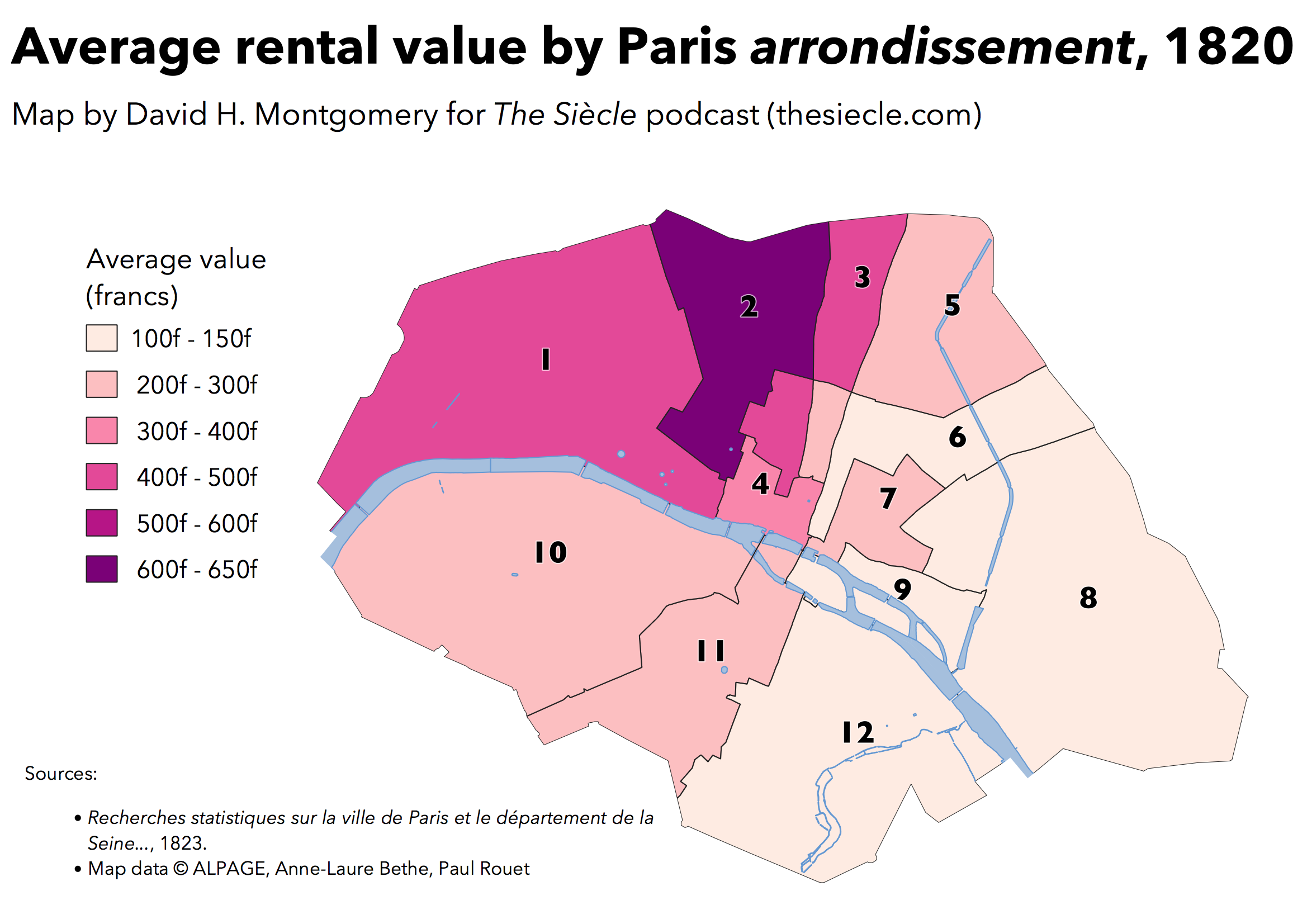

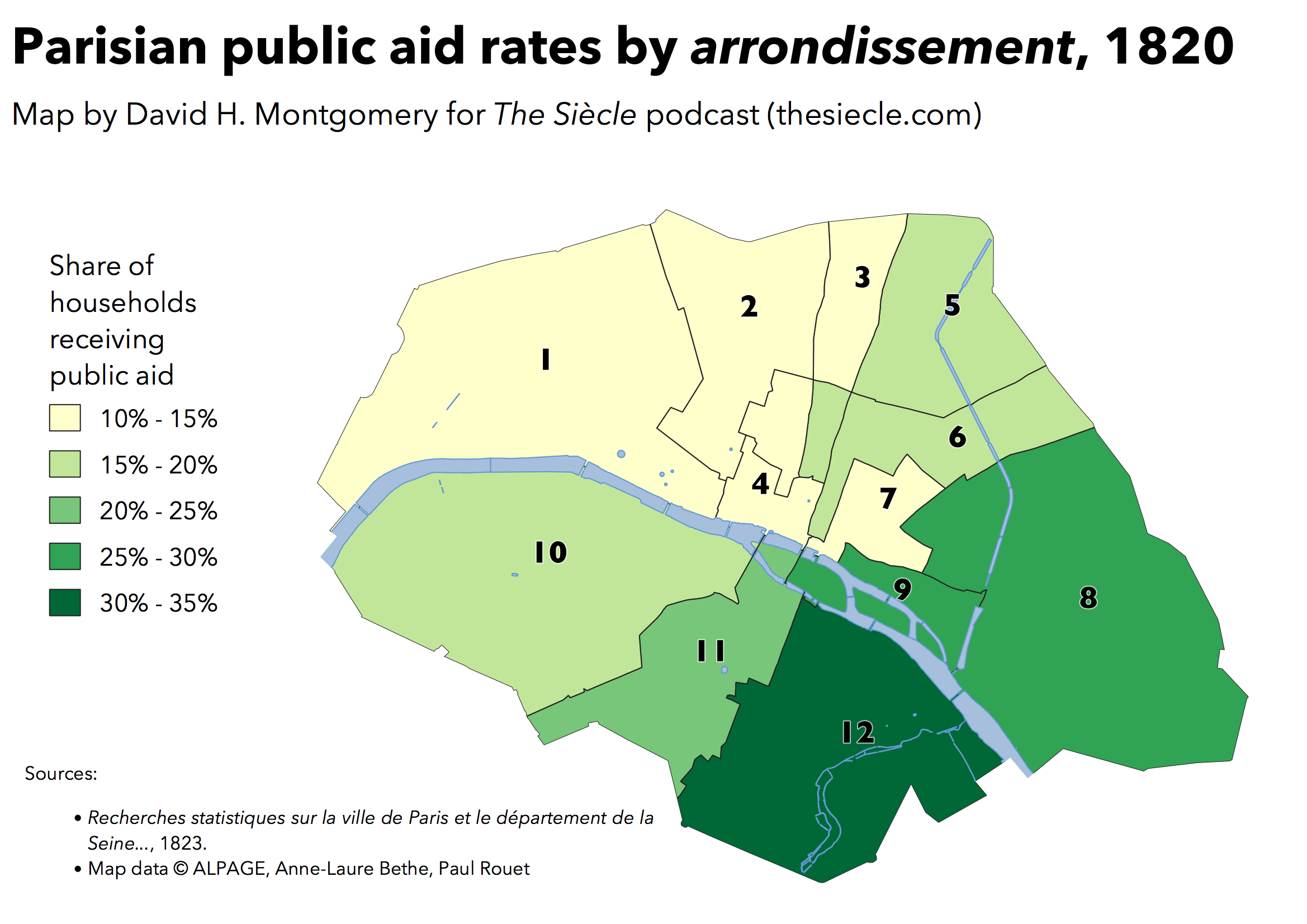

The fundamental socioeconomic division of Paris in 1815, as for much of the century, was between the working-class eastern districts of the city, and the wealthier western districts. This overlapped somewhat with the more famous division between the part of the city on the Left Bank of the Seine and that on the Right Bank. During the Bourbon Restoration, many of the richest neighborhoods were indeed on the Right Bank — but the western sections of the Left Bank included the Faubourg Saint-Germain, where the oldest of the old money lived. Western arrondissements, or districts, in general had the highest housing prices and the lowest share of households receiving public assistance.7

Meanwhile the eastern sections had the lowest rents and the largest share of the population receiving welfare.

You can visit thesiecle.com/episode4 to see some maps I made of rents and public assistance by arrondissement in Restoration Paris.

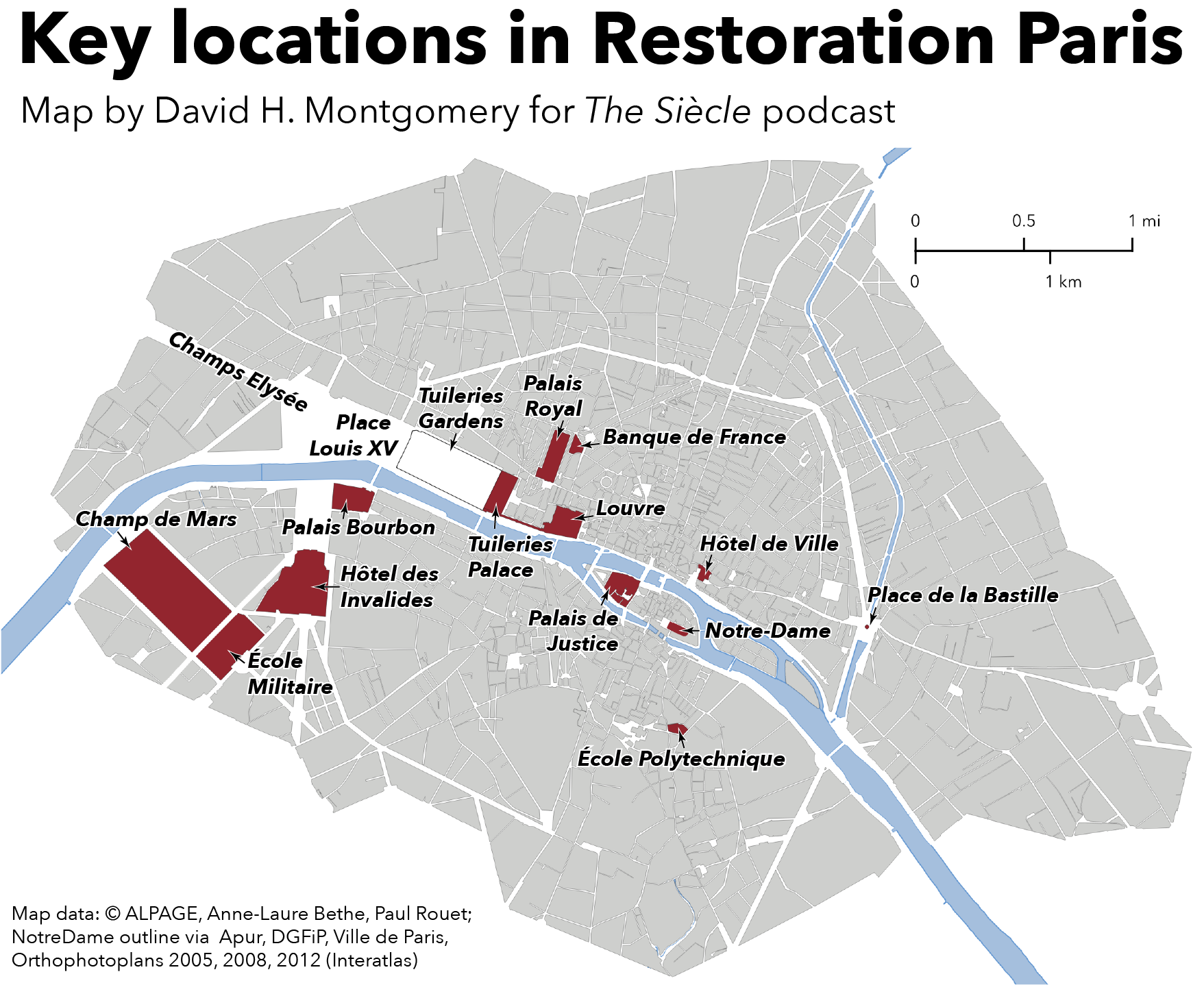

If we wanted a grand view as we walk into Paris, we might enter the city from the west, on the Route de St. Germain. In a grand square in front of the city gates looms an incomplete monument: the Arc de Triomphe, not to be finished for nearly two more decades. In 1815 it’s located outside of Paris proper, welcoming us into the city rather than a plaza in its heart. Still, we could process down a broad avenue toward the Tuileries Garden, and then to the Louvre, just like today. Instead of grand buildings, though, the Champs-Élysées is surrounded by forested parkland — or should be, but depending on when we arrive in 1815, those trees might have been chopped down for firewood. You’ll have to wait until next episode for more on that.

At the end of the Champs-Élysées is a vast square where, a generation earlier, guillotines executed Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Robespierre and others in front of huge crowds in the Place de la Révolution. Later revolutionaries, embarrassed by the Reign of Terror, renamed it the Place de la Concorde. But the new king, Louis XVIII, has returned the square where his brother was killed to its pre-revolutionary name: the Place Louis XV.

Ahead of us lies the vast Tuileries Garden, “one of the main meeting places of middle class and even poor Parisians.” Beyond these gardens is the Palace of the Tuileries — no longer there in the 21st Century — where 19th Century French monarchs will live and govern. From balconies, Louis can wave to the crowds in the garden below, and once, immediately after his second Restoration in 1815, even descend to walk among the masses.8

Were we to turn north from the Place Louis XV, we’d find ourselves on the Grands Boulevards, a wide, modern ring-road on the site of Paris’s old medieval wall. These are a busy center of Restoration social life. Parisians of all stripes can appreciate the streetside benches and the many theaters in the Boulevard du Temple — nicknamed the “boulevard of crime” not for its pickpockets, but for its melodramas. Better-off Parisians also like the boulevards’ smooth streets, so much more capable of handling carriages than the winding warrens of the old city, and the cafés and restaurants of the Boulevard des Italiens.9

Those restaurants — the ones on the Boulevard des Italiens, and hundreds of others scattered throughout the city — are worth dwelling on for a moment. Today we take it for granted that a city like Paris will have great restaurants. But the “restaurant” was in fact quite new in 1815, having emerged in the second half of the 18th Century. With such novelties as meals made to order, table service, and a menu listing all your options and how much they cost in advance, as well as elaborate decorations and, of course, the food itself, the restaurant was seen as quintessentially Parisian. Famous restaurants like the posh Véry restaurant in the Palais Royal fed everyone from Balzac to innumerable foreign travelers. A fancy meal could cost as little as two francs, to the perpetual astonishment of visitors from Britain, where prices were much higher — though meals could also be far more expensive in Paris, depending on the food and drink you ordered, and even two francs was about two days’ wages for a common laborer.10 The Parisian restaurants of the 19th Century deserve an episode of their own, and might get one; in the meantime, if you want to learn more, I heartily recommend historian Rebecca Spang’s fascinating book, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture.

Outside of the ring of boulevards, Paris was not yet fully developed. The main roads in and out of the city are densely populated, but further back things spread out. In these more desolate portions of the city you find less desirable businesses, like the reeking charnel house of Montfaucon, or parks, like the Left Bank’s Jardin du Luxembourg, which was much bigger than it is today, but a closed-off private garden for adjoining landowners instead of a public park. In some areas you’d even find fields and pastures inside Paris’s walls!11

But these low-density corners are not at all typical of this teeming metropolis — though they certainly highlight its many contradictions. The central parts of Paris are as densely populated as it gets — the central 4th arrondissement has more than 200,000 people per square mile, or 77,000 per square kilometer, about three times as dense as modern-day Manhattan.12 Some ritzy mansions and townhomes aside, Restoration Paris is a city of multi-family housing. The city averaged more than eight housing units per residential building, and even the less-dense arrondissements average more than six units per home.13

In the densest quarters of the city, on the Right Bank near the Seine and the central palaces, people were packed on top of each other. The Carrousel neighborhood lay on the doorstep of the king’s palace, in between the Tuileries and the Louvre, but it was a warren of shacks, old townhomes, and “waste ground where mountebanks, dog-clippers and tooth-pullers plied their trades.”14 Even more destitute was the famous Île de la Cité in the middle of the Seine, a collection of medieval hovels in the shadow of Notre Dame. Novelist Eugène Sue described this neighborhood thusly:

The mud-colored houses, pierced by a few windows with worm-eaten frames, almost touched each other at the top because the streets were so narrow. Dark and filthy alleyways led to even darker and filthier stairways that were so steep one could barely climb them by holding on to a rope attached to the humid walls by iron hooks.15

Far from the newer grand boulevards, the physical streets of the old city were very un-picturesque. These tended to be paved with “big, badly joined blocks of sandstone” with no sidewalks, and they sloped down toward the center, forming a gutter in the middle of the road. When it rained, these could become veritable rivers running down the center of streets — a situation made more disgusting by residents’ habit of throwing “their daily garbage and night soil indiscriminately” out into these gutters as well as the droppings of countless horses.16 Enterprising locals would lay planks across these open-air sewers and charge a toll to people for the privilege of crossing the street without getting one’s clothes filthy.17

Other neighborhoods were less terrifying to Paris’s nobility and bourgeois, even if rich and poor neighborhoods often remained just a stone’s throw apart. The Faubourg Saint-Germain, on the Left Bank, was home to the mansions of the old nobility — “elegant residences protected from the noisy streets by courtyards and portals often guarded by a doorman” — while across the river the Chaussée d’Antin neighborhood was home to newer money — “the fief of big bankers” and “newly rich luxury” rather than the quiet of the so-called “Noble Faubourg.”18

There is a widespread belief that the Paris of this time was a city where rich lived in the same buildings as the poor — the wealthy on the first-floor apartments, in this pre-elevator era, and poorer and poorer families in higher apartments. This appears to be true, but only to a degree. Rents absolutely did fall as you went higher up in buildings. In one prime location, a second-floor apartment would cost 600 francs per month — more than many unskilled laborers would earn in a year — while an attic would be more than 10 times cheaper at 40 francs per month.19 But historian Robert Carlisle argues that class lines were largely maintained, with “the same sorts of people” living “within the same walls.” Instead of a banker on the first floor and chimney-sweeps in the attic, a building might have a banker on the first floor, a young lawyer on the next floor, and a clerk in the attic — mixing within classes, rather than between them.20

At the center of Paris, along the Seine, are the key locations where so many of the century’s events will take place. We’ve already met the Tuileries Palace, where the king lived and held court. The Tuileries faced its gardens on one side; on the other was the Cour du Carrousel, where an endless array of carriages would pull up, picking up and dropping off visitors to the palace.21 Across the crowded Carrousel neighborhood was the Louvre, already a world-class art museum; the two palaces were connected by the Grand Gallery running along the riverfront.

North of the Tuileries was the Palais-Royal, a palace owned by the king’s cousin, Louis-Philippe, the duc d’Orléans. Parts of the Palais-Royal had been converted into a shopping center, with numerous boutiques, cafés and restaurants; it was also a popular gathering place and the residence of the Orléans family, who we’ve met before in this podcast and will meet again.22

If you continue east along the river from the Louvre, through more overcrowded neighborhoods, you come to the Hôtel de Ville, the Paris city hall and a symbol of Paris’s power and authority, as opposed to the national authority symbolized by the Tuileries. About a mile further east is another symbol of opposition to national power: the Place de la Bastille, on the site of the ancien régime prison famously stormed by the revolutionary mob. The Place de la Bastille is also near the eastern terminus of the arc of Grands Boulevards that begin in the west near the Tuileries Gardens and the former Place de la Concorde.

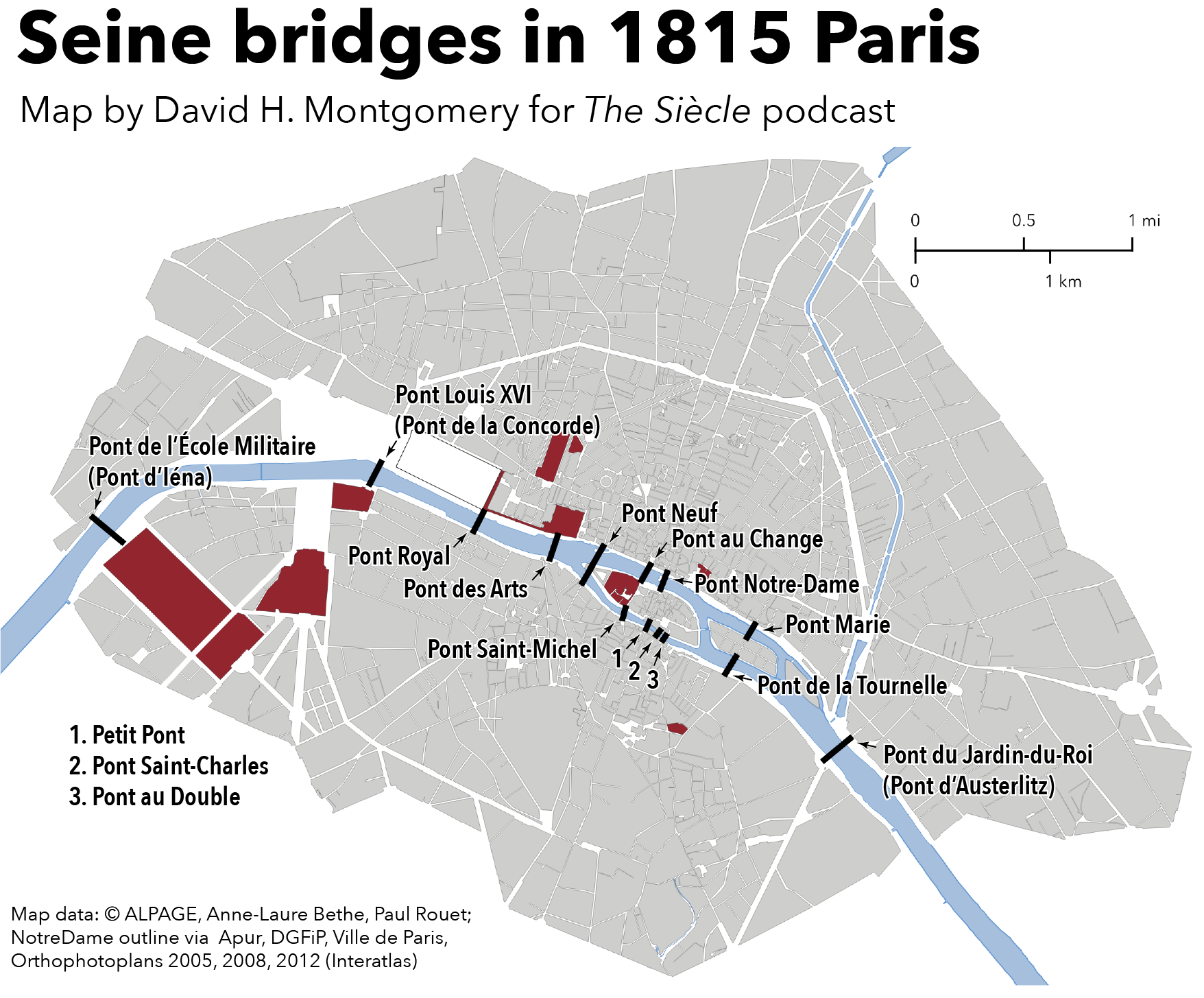

The Seine itself was crossed then by 14 bridges in Paris, some of them quite new. You can see a map of these bridges online at thesiecle.com/episode4. From west to east, the bridges of 1815 are:

- The Pont d’Iéna or the Bridge of Jena, a new bridge named after a Napoleonic victory over the Prussians, which connects the Right Bank to the vast field of the Champ de Mars and the Parisian military academy. In an attempt to soothe the feelings of the now-victorious Prussians, it has just been renamed the Pont de l’École Militaire, or Bridge of the Military Academy.

- The Pont Louis XVI, or the Louis XVI Bridge, which runs from the Place Louis XV — formerly known as the Place de la Concorde, where the Champs-Élysée meets the Tuileries gardens — to the left bank, where you can find the famous riverside walk, the Quai d’Orsay, and Palais Bourbon, where the French Chamber of Deputies, or parliament, meets.

- The Pont Royal, or Royal Bridge, which crosses to the left bank from the Tuileries Palace.

- The Pont des Arts, or Bridge of the Arts, a new, metal bridge crossing the Seine by the Louvre.

- The Pont Neuf, or New Bridge, ironically was then and now the oldest standing Seine bridge, completed around 1607. The Pont Neuf’s two spans connect the Right Bank to the western end of the Île de la Cité, and the Île de la Cité to the Left Bank. At the center of the bridge will, in a few years, be constructed a statue of French King Henri IV, the founder of the Bourbon dynasty and a symbol of the Restoration. The statue, a reconstruction of an earlier statue that had been destroyed during the Revolution, will be constructed in part from a melted-down statue of Napoleon.23

- The Pont au Change and Pont Saint-Michel, or Bridge of Change and Saint-Michael Bridge, connect the Right and Left banks respectively to the center of the Île de la Cité, with the road between them running by the Palais du Justice, or Palace of Justice, a prominent court building.

- The Pont Notre-Dame and Petit Pont, or Notre-Dame Bridge and Little Bridge, connect the Right and Left banks respectively to the Île de la Cité, with the road between passing near the Cathedral of Notre-Dame.

- The Pont Saint Charles and the Pont au Double, or the St. Charles Bridge and Bridge of the Double, are two small spans connecting the Île de la Cité to the Left Bank, both also near Notre-Dame.

- The Pont Marie and Pont de la Tournelle, or Marie Bridge and Bridge of the Turret, link the Right and Left banks respectively to the Île Saint-Louis, a quiet and wealthy natural island in the middle of the Seine.

- The Pont d’Austerlitz, named after Napoleon’s great victory, is the final bridge across the Seine. Constructed under Napoleon, it links the working-class Faubourg Saint-Antoine on the Right Bank with the royal gardens and zoo at the Jardin des plantes or Jardin-du-Roi on the Left Bank, both near the far eastern side of Paris. Similar to the Pont d’Iéna, this has just been renamed the Pont du Jardin-du-Roi, or Bridge of the Royal Gardens, to avoid offending the losers at Austerlitz, the Prussians and Russians.

If you visit Paris today, you’ll find more bridges crossing the Seine in central Paris than the 14 I just listed, but those were built after 1815. Additionally, some of the bridges I mentioned have been replaced by new structures in the same location bearing the same name, or destroyed altogether.

There are plenty of additional important sites in 1815 Paris that I’ve omitted, some intentionally, others inadvertently. But hopefully this gives you a general understanding of the landscape of France’s capital during the Restoration, and some hints about what life was like there. As I mentioned earlier, I’ll be delving more deeply into daily life in a future episode.

If you’re liking this show, I’d appreciate it if you’d spread the word to your friends and followers on social media. You can find The Siècle on both Twitter and Facebook at @thesiecle, t-h-e-s-i-e-c-l-e. At thesiecle.com/episode4 you can view the script for this episode with maps, arts, and citations. You can also visit thesiecle.com/support for ways you can support the podcast financially if you feel so inclined — every dollar helps me continue researching, writing and recording the show.

I’d like to specifically thank two people for their support: Rasmus Andersson, who became The Siècle’s first supporter on Patreon, and Mark Giga, who purchased David Pinkney’s Decisive Years in France, 1840-1847 for me off the show’s Amazon wish list. Your support makes a big difference! Again, you can find out more ways to support the show at thesiecle.com/support.

For now, we’re going to wrap up our two-episode tour of 1815 France and return to the narrative. We last left off after the Battle of Waterloo, when Louis XVIII was restored to his throne for the second time. When we return, we’ll look into the bloody and divisive aftermath of Waterloo, when foreign armies and French royalists exert their authority and seek vengeance. Check back in in two weeks for The Siècle Episode 5: The White Terror.

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 377. ↩

-

Honoré de Balzac, The Girl with the Golden Eyes, translated by Ellen Marriage (1835, Project Gutenberg ebook, 2016). ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 355. ↩

-

Robert B. Carlisle, The Proffered Crown: Saint-Simonianism and the Doctrine of Hope (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 16. ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 366. De Saint-Julien, A. and G. Bienaymé, Histoire des droits d’entrée & d’octroi à Paris, Tableaux, 18, 32, 60. ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 370-2. ↩

-

Recherches statistiques sur la ville de Paris et le département de la Seine […]., Paris: L’Imprimerie Royale, 1823. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 212, 257-8. ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 370, 382. ↩

-

Rebecca L. Spang, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture (Cambridge, Mass., and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2000), 170-206. Christine Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies: The Occupation of France After Napoleon. (Cambridge, Mass., and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2018), 188. ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 370-1. ↩

-

Carlisle, The Proffered Crown, 18. ↩

-

Recherches statistiques, Tableau no. 102. ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 368. ↩

-

Eugène Sue, Les Mysteres de Paris, quoted in Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 368. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration., translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 258 ↩

-

Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 372. Carlisle, 16. ↩

-

De Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration., 259-62. ↩

-

De Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration., 259. ↩

-

Carlisle, The Proffered Crown, 18. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 283. ↩

-

Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 48. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 115-6. Victoria E. Thompson, “The Creation, Destruction and Recreation of Henri IV: Seeing Popular Sovereignty in the Statue of a King,” History and Memory, 24, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2012). ↩