Fact Check 3: Polignac's Visions

In July 1830, King Charles X of France and his prime minister Jules de Polignac launched a coup, unilaterally dissolving parliament, censoring the press, and re-writing the election laws. But after launching this bold stroke, Polignac proceeded to sit around and do basically nothing. There were no soldiers to secure the streets, no arrests of opposition leaders — just business-as-usual for a situation anything but usual. A few days later, a popular revolution had driven Polignac out of office and Charles off his throne, an event now called the “July Revolution.” I covered all that starting in Episode 39.

In July 1830, King Charles X of France and his prime minister Jules de Polignac launched a coup, unilaterally dissolving parliament, censoring the press, and re-writing the election laws. But after launching this bold stroke, Polignac proceeded to sit around and do basically nothing. There were no soldiers to secure the streets, no arrests of opposition leaders — just business-as-usual for a situation anything but usual. A few days later, a popular revolution had driven Polignac out of office and Charles off his throne, an event now called the “July Revolution.” I covered all that starting in Episode 39.

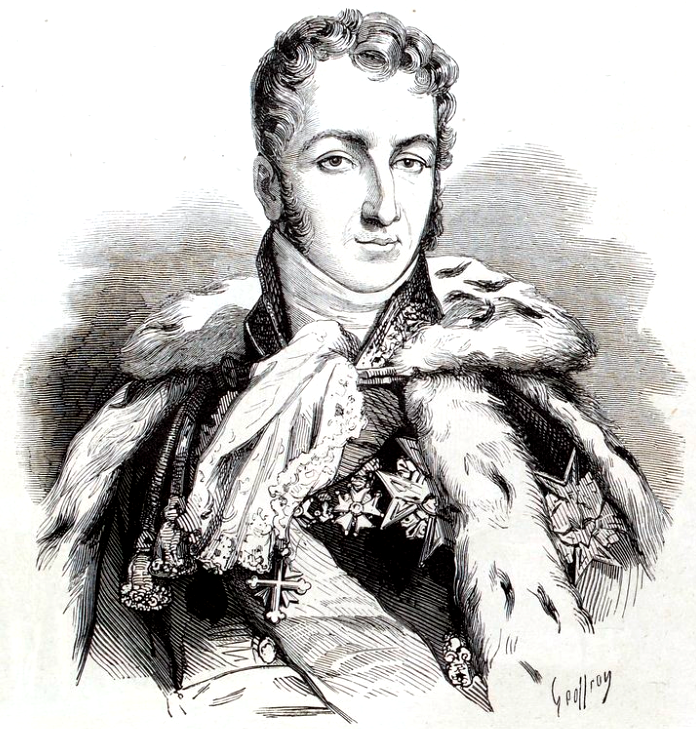

Right: Geoffroy, “Jules de Polignac,” in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

But one thing I didn’t cover is the question of why Polignac was so incompetently unconcerned as Paris spiraled out of his control. It’s possible, as my guest Mike Duncan said of Charles in Episode 46, that Polignac was simply one of the “great idiots of history.” Or perhaps the better quote is from the movie All the President’s Men, about the Watergate break-ins: “The truth is, these are not very bright guys, and things got out of hand.”

But lots of people then and ever since have offered up another explanation for Polignac’s bizarre behavior — a controversial claim. Because if you believe some of the sources, Jules de Polignac had reasons for confidence beyond earthly logic: He was receiving guidance from the Virgin Mary.

This is The Siècle, Fact-Check 3: Polignac’s Visions.

Welcome back, everyone!

This episode was supposed to be short. A few thousand words, maybe 15 minutes of audio, wrapping up a loose end from the July Revolution.

But then I got researching. One loose end led to another. And suddenly I was delving into the history of Christian theology, cross-referencing a half-dozen French-language memoirs, and spending altogether too much time getting to know the mind of Jules de Polignac. And I’m really proud of the result, even if it took me two weeks longer than I intended and there are more words in my footnotes than the entire episode was supposed to have.1

If you like this kind of seriously researched, carefully written history podcast, then I encourage you to support the show on Patreon. As a rough rule of thumb, every minute of edited audio in an episode of The Siècle represents an hour of work on my part: research, writing, editing, recording, and editing. Your support makes it easier for me to justify spending all that time on my nights and weekends — and in return, all patrons get access to an ad-free feed of the show. Join new patrons Bert Slagman, Cameron VanIderstine, Matthew Henry, Alex Steele, Robey Pointer, J dub, Shubham, and Alex Bikbaev at thesiecle.com/support.

Finally, I want to thank this show’s network, Evergreen Podcasts.

Now, let’s get into the episode. King Charles X’s prime minister, Jules de Polignac, is said to have received divine visions during the July Revolution, assuring him that everything was going to be all right, that he just needed to stay the course.

And I am not here to tell you that this is flat-out a lie. It is absolutely possible that Polignac, a devoted Catholic, believed himself to be receiving visions from Mary, mother of Jesus.

But you may have noticed that I did not reference this widely cited story in any of my episodes covering the July Revolution. That’s because the sourcing on this is frankly dubious — just a collection of second- and third-hand accounts. It could be true. But skepticism is warranted. Let’s examine these claims, their broader context, and assess just how much we should believe them.

Below: Raphael, “Madonna del Granduca,” 1505. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Before we begin, though, I want to make sure we’re all on the same page, regardless of our religious or academic backgrounds. In Christianity, Jesus, the son of God, was born to a woman named Mary. Part of what made this miraculous is that Mary at the time was a virgin. Instead, as an angel told Mary’s husband Joseph in a dream, according to the book of Matthew, chapter 1, verse 20: “the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.”2 As a result, subsequent Christians have venerated Mary as the Virgin Mary, Mother of God. Roman Catholics in particular have tended to give Mary a prominent place in their theology and worship. In the Catholic tradition, Mary is held to have been not simply a virgin when she gave birth to Jesus, but a perpetual virgin throughout her life. She is held to have been taken up into heaven, body and soul — the Assumption. Catholics hold that Mary, along with other saints, can intercede with God on behalf of humans. Another doctrine, the Immaculate Conception, holds that Mary herself was born without sin — though more on this later.3

Before we begin, though, I want to make sure we’re all on the same page, regardless of our religious or academic backgrounds. In Christianity, Jesus, the son of God, was born to a woman named Mary. Part of what made this miraculous is that Mary at the time was a virgin. Instead, as an angel told Mary’s husband Joseph in a dream, according to the book of Matthew, chapter 1, verse 20: “the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.”2 As a result, subsequent Christians have venerated Mary as the Virgin Mary, Mother of God. Roman Catholics in particular have tended to give Mary a prominent place in their theology and worship. In the Catholic tradition, Mary is held to have been not simply a virgin when she gave birth to Jesus, but a perpetual virgin throughout her life. She is held to have been taken up into heaven, body and soul — the Assumption. Catholics hold that Mary, along with other saints, can intercede with God on behalf of humans. Another doctrine, the Immaculate Conception, holds that Mary herself was born without sin — though more on this later.3

That’s a one-paragraph summary of issues that Christian theologians and denominations have been arguing about for literal millennia, so please forgive any omitted nuance!

Additionally, I do want to note first that this episode is going to be concerned with whether or not Jules de Polignac believed he was experiencing visions from the Virgin Mary. If Polignac did believe himself to be experiencing these apparitions, then the question of whether his visions were actually divine or of mundane origin is beyond the scope of this history podcast. Got it? Alright, let’s look at the evidence.

“Jules has seen the Holy Virgin again”

The most important story of Polignac’s visions is the most detailed and the most widely cited. As near as I can tell it was also the first to be written down — though it was not, as we’ll see, the first to be published. This account is relayed to us nearly identically by two different observers in their posthumous memoirs: the centrist politician Étienne-Denis, Baron de Pasquier, and the Orléanist socialite Adèle d’Osmond, Comtesse de Boigne.

The most important story of Polignac’s visions is the most detailed and the most widely cited. As near as I can tell it was also the first to be written down — though it was not, as we’ll see, the first to be published. This account is relayed to us nearly identically by two different observers in their posthumous memoirs: the centrist politician Étienne-Denis, Baron de Pasquier, and the Orléanist socialite Adèle d’Osmond, Comtesse de Boigne.

As Boigne tells it, on Wednesday, July 28, 1830, Charles received a visit at Saint-Cloud from the head of the military academy of Saint-Cyr, an aristocrat named Octave de Broglie-Revel — the first cousin of Duc de Broglie. Broglie-Revel, like many nervous royalists in these days of crisis, tried to persuade Charles that things were going badly. Charles, needless to say, was not convinced, and tried in turn to persuade Broglie-Revel that everything was totally fine: “Jules has seen the Holy Virgin again last night,” Charles reportedly said. “She ordered him to persevere, and promised that all would end well.” Broglie-Revel, though a devout Catholic, “nearly collapsed at this revelation.”4

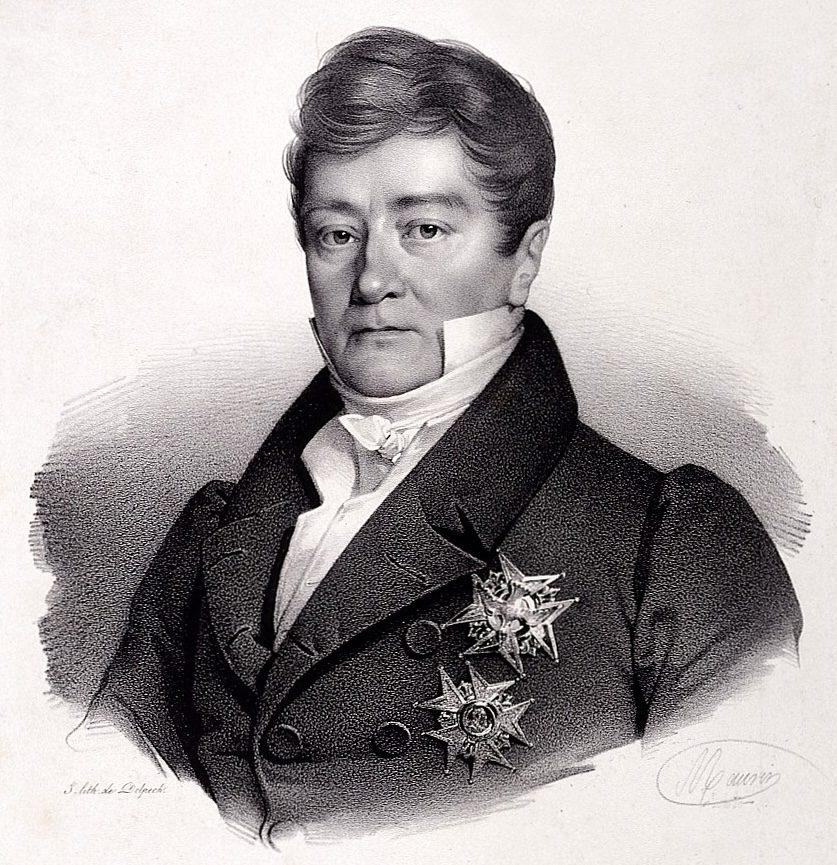

Above: Jean-Baptiste Isabey, “Adélaïde d’Osmond, Comtesse de Boigne,” 1810. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Nicolas-Eustache Maurin, “Étienne-Denis Pasquier,” 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Pasquier tells a very similar story, with Broglie-Revel talking to Charles on Wednesday at Saint-Cloud. In Pasquier’s memoirs, Charles is quoted saying, “I see clearly that I must tell you everything. Well, Polignac had apparitions again last night; he was promised assistance, ordered to persevere, and promised a complete victory.” Pasquier also adds a coda explaining how he — who was in Paris, not Saint-Cloud, at the time — knows of this conversation: “Someone met [Broglie-Revel] coming out of this meeting, holding his head in his hands, in deep distress.” Broglie-Revel told this unnamed person what had just happened. Pasquier concludes, “I learned it from this very person.”5

Pasquier tells a very similar story, with Broglie-Revel talking to Charles on Wednesday at Saint-Cloud. In Pasquier’s memoirs, Charles is quoted saying, “I see clearly that I must tell you everything. Well, Polignac had apparitions again last night; he was promised assistance, ordered to persevere, and promised a complete victory.” Pasquier also adds a coda explaining how he — who was in Paris, not Saint-Cloud, at the time — knows of this conversation: “Someone met [Broglie-Revel] coming out of this meeting, holding his head in his hands, in deep distress.” Broglie-Revel told this unnamed person what had just happened. Pasquier concludes, “I learned it from this very person.”5

These stories differ in some details, but are otherwise very similar. In fact, they’re almost certainly the same story. Pasquier and Boigne are not simply random aristocrats active in Paris society at the same time — they were longtime lovers who were in regular contact during the July Revolution.6 So the fact that we have this from two different people doesn’t necessarily strengthen the case — they probably either heard it from the same person, or one of them told the other.

Confirmation of this story is harder to come by. Broglie-Revel, the man who actually had this conversation, did not write any memoirs. Polignac’s biographer, Pierre Robin-Harmel, says he “unsuccessfully searched the traditions and archives of the House of Broglie for a document on this subject.”7 Neither Pasquier nor Boigne were sympathetic to Polignac, but they were well-connected and might have been the people to hear such gossip. On the other hand, consider how many different people this story had passed through: Polignac supposedly told Charles, who told Broglie-Revel, who told an unnamed person, who told Pasquier, who wrote it down years later in his memoirs. That’s a fairly thin reed to base such a weighty allegation on. So let’s look at our other sources.

“Reasons he could not make known”

The other major accounts of Polignac’s visions date from the 1870s. A note on the chronology is important here. While Pasquier, who died in 1862, and Boigne, who died in 1866, wrote down their accounts of the July Revolution in the years or decades after 1830, their memoirs were not published until much later — Pasquier’s in the 1890s, Boigne’s in the early part of the 20th Century. So while the stories I’m about to tell you were written down after Pasquier’s and Boigne’s accounts, they don’t appear to have had Pasquier or Boigne as sources — at least, not as direct ones.

A German diplomat named Friedrich Geffcken in 1875 published an account, claiming a foreign diplomat told him Charles had mentioned the visions in 1830 to the Russian ambassador, Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo. “Just yesterday the Holy Virgin appeared to Polignac,” Charles supposedly told Pozzo di Borgo. But here again the account is filtered through multiple intermediaries, some unnamed. It’s also possible this is yet again a version of the same story — Pozzo di Borgo was a close friend of Boigne and attended her salon during the July Revolution. Was this a game of “telephone” where a story gets twisted over time as it passes from source to source? We can’t know for certain, but Geffcken’s fourth-hand account is also not especially strong evidence. The alleged timeline when Pozzo di Borgo supposedly had this conversation with Charles also does not match up to the fairly detailed accounts we have of both men’s movements during the July Revolution.8

A German diplomat named Friedrich Geffcken in 1875 published an account, claiming a foreign diplomat told him Charles had mentioned the visions in 1830 to the Russian ambassador, Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo. “Just yesterday the Holy Virgin appeared to Polignac,” Charles supposedly told Pozzo di Borgo. But here again the account is filtered through multiple intermediaries, some unnamed. It’s also possible this is yet again a version of the same story — Pozzo di Borgo was a close friend of Boigne and attended her salon during the July Revolution. Was this a game of “telephone” where a story gets twisted over time as it passes from source to source? We can’t know for certain, but Geffcken’s fourth-hand account is also not especially strong evidence. The alleged timeline when Pozzo di Borgo supposedly had this conversation with Charles also does not match up to the fairly detailed accounts we have of both men’s movements during the July Revolution.8

Above: Artist unknown, “Friedrich Heinrich Geffcken,” 1888. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Maxime du Camp, “Photograph of Maxime du Camp,” between 1847 and 1867. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The writer Maxime du Camp related a version of the story in 1876. Du Camp provides two accounts. First, he says that Charles’s naval minister, Baron d’Haussez, had argued with Polignac before the Four Ordinances were adopted, saying Polignac’s military precautions were inadequate. In response, Du Camp says, Polignac “replied that for reasons he could not make known… he was not allowed to have any doubts about the result” of going forward with the coup. Du Camp follows this vague suggestion by offering an explanation for what Polignac’s “reasons he could not make known” were: that Mary had appeared to Polignac in a dream and told him, “Accomplish your work!” The story, Du Camp notes, “could pass for a fantasy imagined after the fact by an enemy” of the ultraroyalist cause. But he insists he’s not making things up. Instead, Du Camp — who was eight years old in 1830 — says he heard this anecdote directly from a royalist politician, Pierre-Antoine Berryer, who heard it directly from Polignac.9

The writer Maxime du Camp related a version of the story in 1876. Du Camp provides two accounts. First, he says that Charles’s naval minister, Baron d’Haussez, had argued with Polignac before the Four Ordinances were adopted, saying Polignac’s military precautions were inadequate. In response, Du Camp says, Polignac “replied that for reasons he could not make known… he was not allowed to have any doubts about the result” of going forward with the coup. Du Camp follows this vague suggestion by offering an explanation for what Polignac’s “reasons he could not make known” were: that Mary had appeared to Polignac in a dream and told him, “Accomplish your work!” The story, Du Camp notes, “could pass for a fantasy imagined after the fact by an enemy” of the ultraroyalist cause. But he insists he’s not making things up. Instead, Du Camp — who was eight years old in 1830 — says he heard this anecdote directly from a royalist politician, Pierre-Antoine Berryer, who heard it directly from Polignac.9

But Berryer, who died in 1868, years before Du Camp wrote, does not appear to have related any such story in his own writings — at least, none that Polignac’s biographer Pierre Robin-Harmel could find.10 Once again we’re left with an account from a dead source, unable to confirm or contradict the claims attributed to them.

But Berryer, who died in 1868, years before Du Camp wrote, does not appear to have related any such story in his own writings — at least, none that Polignac’s biographer Pierre Robin-Harmel could find.10 Once again we’re left with an account from a dead source, unable to confirm or contradict the claims attributed to them.

Baron d’Haussez, though, did describe his conversations with Polignac about the Four Ordinances in his memoirs. These memoirs, edited by his great-granddaughter, didn’t appear in print until the 1890s, so Du Camp wouldn’t have been able to reference them — though it’s not impossible he had access to a manuscript or other documents from Haussez. But Haussez’s printed memoirs don’t include the conversation Du Camp relates about Polignac being “not allowed to have any doubts.” Instead, Haussez quotes Polignac responding, “Either you recognize the measure as useful, or it does not seem so to you. In the first case, we must adopt it with its drawbacks and dangers; in the second, we must let things go and suffer the consequences.”11

Above: Tony Goutière, “Pierre Antoine Berryer,” 1842. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: David d’Angers, “Auguste Jal and his wife Aspasie (Le Porcher) Jal,” 1834. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Haussez did not hesitate to criticize Polignac in his memoirs, so it’s notable — if not proof of anything — that he doesn’t refer to Polignac’s visions. It’s possible that either Haussez or his great-granddaughter edited these claims out of the final version, but regardless, we’re left with an absence of evidence.

Haussez did not hesitate to criticize Polignac in his memoirs, so it’s notable — if not proof of anything — that he doesn’t refer to Polignac’s visions. It’s possible that either Haussez or his great-granddaughter edited these claims out of the final version, but regardless, we’re left with an absence of evidence.

Finally, we have an account from the naval historian Auguste Jal, in his posthumous 1877 memoirs. Jal was no fan of Polignac, calling him “devoted, but lacking understanding of what was happening around him.” He claims Polignac had visions, and quotes Polignac: “When I am tired, I doze on my couch; then the Virgin appears to me, encourages me, counsels me. I wake up and walk, sure that I will not go astray.” Like Maxime du Camp, Jal follows this story by acknowledging it seems odd coming from him: “This is not a mockery, an invention of liberalism,” he says. And like Du Camp, Jal justifies his story by saying he learned it from a dedicated ultraroyalist: “This matter was related to me seriously by a man of great wit, a strong royalist, but very enlightened, the Duc de Fitz-James, whom I had the honor of seeing often in 1831.”12

Specifically, Jal reports running in to Fitz-James at salons hosted by Lizinska de Mirbel, a painter. Mirbel was a famed salon hostess at this time, and her regular guests did include many ultraroyalists. Whether Fitz-James was among those guests my sources don’t explicitly say, it seems likely. Men in Fitz-James’s circles including the Duc de Duras did attend Mirbel’s salons, and Mirbel also painted a portrait of Fitz-James circa 1827. So the idea that Jal might have attended Mirbel’s salons in 1831 and encountered Fitz-James there is at least somewhat plausible.13 But Fitz-James himself, though an ultraroyalist and a member of Charles’s royal court, was hostile to Polignac, and was out of the country during the July Revolution.14 So he could not have been, say, the anonymous figure who relayed Broglie-Revel’s July 28 story to Pasquier. It is possible Fitz-James heard about Polignac’s visions before the revolution. But we can’t know — Fitz-James also did not write any memoirs and had been dead for decades before Jal cited him.

Below: Jacques Étienne Pannier after Lizinska de Mirbel, “Édouard de Fitz-James, duc de Fitz-James,” 1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

We need to note some more connections here! For example, Du Camp’s source, Berryer, knew Fitz-James quite well during this period in the early 1830s when Fitz-James supposedly told Jal about Polignac’s visions.15 So if you believe Fitz-James knew about Polignac’s visions in 1831, as Jal claims, then that strengthens Du Camp’s claim that Berryer knew. Fitz-James also knew Boigne: years before, she had been self-described “best friends” with Fitz-James’ first wife.16 If this is a lot to keep track of, trust me — it was a real headache to research, too!

We need to note some more connections here! For example, Du Camp’s source, Berryer, knew Fitz-James quite well during this period in the early 1830s when Fitz-James supposedly told Jal about Polignac’s visions.15 So if you believe Fitz-James knew about Polignac’s visions in 1831, as Jal claims, then that strengthens Du Camp’s claim that Berryer knew. Fitz-James also knew Boigne: years before, she had been self-described “best friends” with Fitz-James’ first wife.16 If this is a lot to keep track of, trust me — it was a real headache to research, too!

In any case, the weight of these multiple reports about Polignac’s visions does add up, but none of them are especially robust. We’ve got a lot of second- and third-hand claims, from anonymous or dead sources. No one close to Polignac reports the story directly.17 The closest we get is a passing reference from Polignac’s fellow minister, Martial de Guernon-Ranville, who wrote in his diary on April 20, 1830:

Polignac, whom I would sometimes be tempted to believe to be guided by influences quite beyond the ministerial sphere, now seems convinced that we will only be able to emerge victorious from this battle by resorting to some extraordinary measure, by applying Article 14 of the Charter.18

This isn’t exactly confirmation of the charge, but it is a kind of character witness. People who were close to Polignac found it plausible that he thought he was receiving divine guidance.

We’re left in a kind of muddle. It’s certainly possible Polignac believed himself receiving visions, but the direct sources we have to it are all somewhat lacking. So perhaps it’s time to step back and look at the bigger picture — what does it mean for people to say Jules de Polignac thought he had visions of the Virgin Mary in July 1830?

There’s something about Mary

On Sunday, July 11, 1830, two weeks before Charles signed the Four Ordinances, the king attended mass at Paris’s Cathedral of Notre Dame — that is, the cathedral of “Our Lady,” the Virgin Mary. In attendance were Polignac, the rest of Charles’s ministers,19 and a host of other dignitaries. The occasion was a celebratory mass for France’s recent conquest of Algiers. The Archbishop of Paris, Hyacinthe-Louis de Quélen, said in a sermon that the victory showed God’s hand was with Charles, and told the king that his “confidence in divine help and the protection of Mary, Mother of God, will not be in vain.”20

On Sunday, July 11, 1830, two weeks before Charles signed the Four Ordinances, the king attended mass at Paris’s Cathedral of Notre Dame — that is, the cathedral of “Our Lady,” the Virgin Mary. In attendance were Polignac, the rest of Charles’s ministers,19 and a host of other dignitaries. The occasion was a celebratory mass for France’s recent conquest of Algiers. The Archbishop of Paris, Hyacinthe-Louis de Quélen, said in a sermon that the victory showed God’s hand was with Charles, and told the king that his “confidence in divine help and the protection of Mary, Mother of God, will not be in vain.”20

Right: Unknown artist, “Hyacinthe-Louis de Quélen, Archbishop of Paris,” 19th Century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At risk of stating the obvious, the Virgin Mary was an important figure in Roman Catholic belief and religious practice in 1830, as this example shows. Devout Catholics around Charles, like Archbishop de Quélen, thought and spoke of Mary specifically as someone who provided divine help and protection to King Charles. That doesn’t necessarily mean Polignac was seeing visions of Mary, of course, but it suggests an environment where that suggestion makes some sense.

On the other hand, July 1830 is actually a really interesting time to talk about Mary’s place in Roman Catholicism. The 1500s and 1600s had seen a “Marian movement” that raised up new forms of devotion to Mary, partially as a response to the Protestant Reformation which had de-emphasized Mary. But by the mid-18th Century this Marian movement receded. The first 30 years of the 19th Century, scholar René Laurentin writes, “are perhaps the most barren in the history of Marian literature.”21

Then comes July 1830, when a vision of the Virgin Mary in Paris starts a chain reaction that will transform Catholic veneration of Mary. But we’re not talking about Jules de Polignac. Instead, we’re looking at a 24-year-old nun named Catherine Labouré, who was living in a convent in Paris when she reported that Mary had appeared to her on the night of July 18. (That’s one week after De Quélen’s sermon at Notre Dame, and one week before the Four Ordinances.) In the vision, Mary told Catherine she would soon receive a divine mission. A few months later, on November 27, Labouré received a second vision of Mary, in which the Mother of God ordered her to create a religious medal with the slogan, “O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee.” Further, Labouré was to tell people that “those who wear [the medal], blessed, around their necks, and who confidently say this prayer, will receive great graces and will enjoy the special protection of the Mother of God.”22

Then comes July 1830, when a vision of the Virgin Mary in Paris starts a chain reaction that will transform Catholic veneration of Mary. But we’re not talking about Jules de Polignac. Instead, we’re looking at a 24-year-old nun named Catherine Labouré, who was living in a convent in Paris when she reported that Mary had appeared to her on the night of July 18. (That’s one week after De Quélen’s sermon at Notre Dame, and one week before the Four Ordinances.) In the vision, Mary told Catherine she would soon receive a divine mission. A few months later, on November 27, Labouré received a second vision of Mary, in which the Mother of God ordered her to create a religious medal with the slogan, “O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee.” Further, Labouré was to tell people that “those who wear [the medal], blessed, around their necks, and who confidently say this prayer, will receive great graces and will enjoy the special protection of the Mother of God.”22

Above: Unknown artist, “Catherine Labouré,” unknown date. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Alois Gege, “The Apparition of Mary in Paris, 1830 (Katherina Labouré),” 19th Century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Labouré reported these visions to her confessor, Father Jean Marie Aladel — who was skeptical. “I saw nothing in it but the work of her imagination,” Aladel later wrote. “When the vision recurred… I attached no more importance to it this time, and I dismissed her as before.” But when Labouré reported another vision in September 1831, in which Mary complained that the medal had not been struck, Aladel took the matter to the Archbishop of Paris — the same Hyacinth-Louis de Quélen who preached about Mary’s protection in July 1830. De Quélen said that Labouré’s visions seemed in keeping with Church doctrine, and that “he wished himself to be the first to be given such a medal.” The medals were struck in 1832, and soon became massively popular, with millions of copies produced throughout the 1830s. It soon acquired the name, the “Miraculous Medal,” and is still worn by many Catholics to this day.23

Labouré reported these visions to her confessor, Father Jean Marie Aladel — who was skeptical. “I saw nothing in it but the work of her imagination,” Aladel later wrote. “When the vision recurred… I attached no more importance to it this time, and I dismissed her as before.” But when Labouré reported another vision in September 1831, in which Mary complained that the medal had not been struck, Aladel took the matter to the Archbishop of Paris — the same Hyacinth-Louis de Quélen who preached about Mary’s protection in July 1830. De Quélen said that Labouré’s visions seemed in keeping with Church doctrine, and that “he wished himself to be the first to be given such a medal.” The medals were struck in 1832, and soon became massively popular, with millions of copies produced throughout the 1830s. It soon acquired the name, the “Miraculous Medal,” and is still worn by many Catholics to this day.23

Several things are worth briefly noting about the story of Labouré and the Miraculous Medal.

The first is that while Labouré’s visions were preceded by that barren period in Marian literature, they were followed by a number of high-profile visions of Mary in subsequent decades. In 1842 a 27-year-old banker named Alphonse Ratisbonne became a sensation after converting from Judaism to Catholicism after reporting a vision of Mary in Rome.24 In 1846 two shepherds aged 11 and 14 reported meeting a woman wreathed in light near the village of La Salette high in the French Alps. And most famously, in 1858, a 14-year-old girl named Bernadette Soubirous reported a series of visions of a young woman, swiftly identified as Mary, at the town of Lourdes in the Pyrenees. All of these visions provoked widespread public interest. And they all took place before any of these accounts of Polignac’s Marian visions were published.25

The first is that while Labouré’s visions were preceded by that barren period in Marian literature, they were followed by a number of high-profile visions of Mary in subsequent decades. In 1842 a 27-year-old banker named Alphonse Ratisbonne became a sensation after converting from Judaism to Catholicism after reporting a vision of Mary in Rome.24 In 1846 two shepherds aged 11 and 14 reported meeting a woman wreathed in light near the village of La Salette high in the French Alps. And most famously, in 1858, a 14-year-old girl named Bernadette Soubirous reported a series of visions of a young woman, swiftly identified as Mary, at the town of Lourdes in the Pyrenees. All of these visions provoked widespread public interest. And they all took place before any of these accounts of Polignac’s Marian visions were published.25

Above: Virgilio Tojetti, “Painting of the apparition of Virgin Mary to Bernadette Soubirous in the Grotto at Massabielle near Lourdes,” 1877. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Xhienne, “Medal of the Immaculate Conception (aka Miraculous Medal),” Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license via Wikimedia Commons.

You might note that Labouré and Ratisbonne were both in their 20s at the time of their visions, while Soubirous and the shepherds of La Salette were between 11 and 14. Jules de Polignac, in contrast, was 50 years old and the prime minister of France when he supposedly had his.

Another key difference: Labouré, Ratisbonne, the shepherds of La Salette and Soubirous all promptly reported their visions to Catholic priests, who arranged — sooner or later — for inquiries into the visions. Because whether you are a believer or a skeptic about miraculous visions, the Catholic Church does not simply accept all claims. It has a process. In all of these cases, these official Church inquiries reached the conclusion that the reported visions were miraculous. For example, in the case of Labouré, the vicar general of the diocese of Paris interviewed 48 witnesses over six months, all driving at whether Labouré was telling the truth about her visions, or whether she was “a deceitful liar or a self-deceived fanatic.” The inquiry resulted in a 10,000-word report, concluding that Labouré’s visions seemed “worthy of credence.” Labouré and Soubirous were later beatified and are now recognized as saints by the Catholic Church.26 My sources do not record any Church inquiry of any form into Polignac’s supposed visions.27

Second, you might have noted that Labouré’s Miraculous Medal bears the slogan, dictated to her from her visions, “O Mary, conceived without sin.” That’s the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception I talked about earlier. Except in 1830 the Immaculate Conception was not Catholic doctrine. It was a popular Catholic belief about Mary, but not one officially endorsed by the Church. Catholic theologians had debated the Immaculate Conception for centuries, with fierce proponents in both camps. St. Thomas Aquinas had written against it; in the 17th century the Inquisition forbid Catholics to describe Mary’s conception as “immaculate.” On the other side, a number of Jesuit writers defended the Immaculate Conception, including the Spanish theologian Francisco Suarez and the Cardinal St. Robert Bellarmine — who is perhaps better known for ordering Galileo to abandon Copernicanism. In 1661, Pope Alexander VII forced a truce by forbidding attacks on either the Immaculate Conception or on the opposing idea that Mary was not conceived without sin. That’s where things officially stood in 1830. But by 1854, sparked in large part by Labouré’s visions and medal, Pope Pius IX would declare the Immaculate Conception to be Catholic doctrine — to widespread acclamation by lay Catholics.28

Second, you might have noted that Labouré’s Miraculous Medal bears the slogan, dictated to her from her visions, “O Mary, conceived without sin.” That’s the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception I talked about earlier. Except in 1830 the Immaculate Conception was not Catholic doctrine. It was a popular Catholic belief about Mary, but not one officially endorsed by the Church. Catholic theologians had debated the Immaculate Conception for centuries, with fierce proponents in both camps. St. Thomas Aquinas had written against it; in the 17th century the Inquisition forbid Catholics to describe Mary’s conception as “immaculate.” On the other side, a number of Jesuit writers defended the Immaculate Conception, including the Spanish theologian Francisco Suarez and the Cardinal St. Robert Bellarmine — who is perhaps better known for ordering Galileo to abandon Copernicanism. In 1661, Pope Alexander VII forced a truce by forbidding attacks on either the Immaculate Conception or on the opposing idea that Mary was not conceived without sin. That’s where things officially stood in 1830. But by 1854, sparked in large part by Labouré’s visions and medal, Pope Pius IX would declare the Immaculate Conception to be Catholic doctrine — to widespread acclamation by lay Catholics.28

That new doctrine, along with the apparitions at Lourdes, were both very recent when these first published reports about Polignac’s visions started to come out in the 1870s. Polignac, meanwhile, died in 1847 — before Lourdes or the official proclamation of the Immaculate Conception, but after Labouré, Ratisbonne, and the shepherds of La Salette had become sensations for their reported visions of Mary. So we shouldn’t dodge the question any more: What does Jules de Polignac have to say for himself?

Jules par Jules

Below: François Gérard, “Jules de Polignac,” circa 1814-1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As it happens, Jules de Polignac had quite a bit to say for himself — but frustratingly absolutely nothing about this precise allegation. Polignac published several books in the 17 years between his downfall and his death, dealing with history, politics, and religion. We also have surviving correspondence between Polignac and a number of family and friends. In none of it does Polignac claim to have had visions. His biographer Pierre Robin-Harmel, who read all of them, concludes that:

As it happens, Jules de Polignac had quite a bit to say for himself — but frustratingly absolutely nothing about this precise allegation. Polignac published several books in the 17 years between his downfall and his death, dealing with history, politics, and religion. We also have surviving correspondence between Polignac and a number of family and friends. In none of it does Polignac claim to have had visions. His biographer Pierre Robin-Harmel, who read all of them, concludes that:

none of [Polignac’s] religious writings gives the impression that Polignac ever believed himself to be blessed with extraordinary graces of prayer. Not only is there not the slightest allusion to this subject, but the most careful theological analysis cannot detect any trace of such a preoccupation.29

Polignac’s writings certainly don’t disprove the allegations. He is absolutely a fervent and devout Catholic, and this is not a cold or formal faith, but a vibrant spirituality. Polignac writes in an 1845 book:

There are some who refuse to recognize any action beyond that of man in the chain of events that fill the centuries… As for me, I declare it frankly here: I am not one of those who rejects divine intervention in affairs of the world. The hand of God rolls the centuries before him, but his wisdom guides the movement he gives them.30

But while Polignac believes that divine providence acts on the world, he never claims to be its specific agent. That is true not only in his published writings, but also in his private letters. Robin-Harmel acidly notes:

If Polignac was so proud of his apparitions that he confided them to many men hostile to his ideas, one may be surprised that during a prolonged intimate correspondence lasting fifteen years with the Baroness de Cetto, his cousin — more than two hundred and fifty letters, all of which we have in our hands — he did not make the slightest allusion to them.31

Robin-Harmel, you may gather, does not believe Polignac saw apparitions. It is strange, he writes, that “only two or three memoirists have related, based purely on hearsay, a fact that by its strangeness should have tempted plenty of other pens.” He acknowledges that there is no definitive proof to the contrary, but says he personally does not believe it. “Polignac can at least be given the benefit of the doubt,” he writes.32

A number of other historians have ended up in between — skeptical, but not dismissive. Charles’s biographer Vincent Beach relays Boigne’s account, and notes that “it may be true, as friends of Polignac have insisted, that the Comtesse de Boigne… was no unbiased observer, and she may have invented this tale,” but Beach goes on to say that “records of Charles X and Polignac and their unusual conduct during the July days indicate that the story could have been true.”33 Munro Price acknowledges Robin-Harmel’s critique of the allegations, before concluding: “The received picture of Polignac in July 1830, praising Our Lady and neglecting the ammunition, may be exaggerated, but it cannot be discounted.”34

Personally, I am mostly in the same place as Robin-Harmel. While it would not shock me if solid evidence emerged to prove it, I think Polignac probably did not believe himself to be seeing visions of the Virgin Mary. The evidence for it is just too weak.

That said, I also don’t think that Boigne, Pasquier, Geffcken, Du Camp, or Jal made up this story. For all the differences in their accounts, there are too many similarities between accounts that appear to have been written entirely independently. I am in the realm of pure speculation here, but my theory is that there was some idle gossip about Polignac in Paris society in the days and years after the July Revolution, gossip that twisted as it passed through multiple hearers before finally getting published as variants of the same story. To me, that’s the best explanation for all these hearsay accounts that never quite get all the way back to Polignac.

But that’s just my take — I’m curious what you think! After the episode, leave a comment or a post on social media with your conclusions about Polignac’s visions.

There’s more to this episode, though. Because the entire reason this story about Polignac’s alleged visions exists is to explain his bizarre behavior during the July Revolution. And we don’t yet have that explanation.

I think this is pretty straightforward, though.

Marian visions aren’t even necessary to explain Polignac’s bizarre complacency during the July Revolution! We know from Polignac’s own hand that he believed God took an active role in shaping world events. And we have his account of the 1789 French Revolution, written in 1845. Polignac says material explanations like national bankruptcy or the Estates-General are insufficient to explain 1789: “such terrible effects,” he writes, “must be traced to causes of a higher order.” Those causes, Polignac continues, were human sin: “impiety had laid its burning hand and demanded victims”; in response, God had “sent [France] anarchy for its own punishment.”35 This kind of theology seems more than enough to explain why someone might feel events were out of his hands without bringing prophetic visions into it.

As it happens, though, this theological approach was not how Polignac explained the July Revolution in the same book. And I wanted to close today by looking at Jules’s own account of his actions. Because while the Virgin Mary is nowhere to be seen, I think we can see an answer to the mystery of Polignac’s behavior.

Above: Vincenzo Carducci, detail from “The Apparition of the Virgin to the Dying Pedro Faverio,” 1624-1634. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Conspiracies

Polignac goes on at length about why he felt issuing the Four Ordinances was Charles’s “right” and “duty,” as a desperate defense of the rights of the crown against “imminent danger threatening the State.” And he insists, to the end, that the Four Ordinances were taken in defense of the Charter, not in defiance of it. I won’t recount all those arguments for you now, except to note that again and again Polignac comes back to one particular menace facing Charles: conspiracies. Polignac writes:

Numerous political societies, both open and secret, spread anarchistic principles throughout the provinces, revived memories of the first revolution, portrayed the Bourbon throne as the sole obstacle to France’s happiness, and spread the most odious accusations against the government.36

And Polignac writes that soon after Charles dissolved the Chamber of Deputies in May 1830, he “obtained a list containing the names of many of those who had joined the secret and public societies that were widespread throughout France.” Polignac said the list was so long, “their sheer number” prevented prosecuting any of these individuals. But these groups, Polignac said, were a “tightly organized network, covering France like a web.” 37

You might notice that Polignac here is combining legal organizations — such as the Aide-toi electoral committees led by François Guizot — with illegal secret societies, who Polignac calls “worthy successors of the old Carbonari movement” which “never ceased to conspire and to support the vehement opposition of their leaders.” All of them, he says, are part of a single powerful movement, centrally directed by a committee in Paris.38

Opposition to Charles and Polignac, he argues, is not a natural, organic reaction to the ministry’s policies. Instead, it’s being spread and controlled by a conspiratorial group.

With that in mind, let’s look at what Polignac did in the weeks leading up to the Four Ordinances. He famously did not move more soldiers into Paris. He did not draw up plans to arrest opposition leaders or control strategic points in Paris. What Polignac did expend energy on in these crucial weeks was keeping the plan secret. Moving soldiers or police, or even telling people who might move soldiers or police, threatened to expose the plot. Instead, Charles’s ministers were sworn to secrecy. Only a single copy of the draft ordinances was kept, and every time a new version was completed, the old version was destroyed. This single copy Polignac kept on his person at all times.39

Polignac never comes out and says so explicitly in his memoirs, but the reason you prioritize secrecy over preparedness in an operation like this is if your primary concern is not letting the enemy plan a response. If the opposition to Charles is being fomented by coordinated societies rather than spontaneous, then you just need to get the drop on the societies.

Polignac’s hard-nosed colleague, Baron d’Haussez, disagreed. He thought the problem with Polignac was that he wasn’t conspiratorial enough. In Haussez’s memoirs, written around 183240 but published decades later, he sneers that Polignac “obstinately denied” the extent of the enemy plot — a plot Haussez says he and the other ministers all believed in “beyond any doubt.” Polignac was trying to get the drop on an enemy that was already three steps ahead.

Polignac’s hard-nosed colleague, Baron d’Haussez, disagreed. He thought the problem with Polignac was that he wasn’t conspiratorial enough. In Haussez’s memoirs, written around 183240 but published decades later, he sneers that Polignac “obstinately denied” the extent of the enemy plot — a plot Haussez says he and the other ministers all believed in “beyond any doubt.” Polignac was trying to get the drop on an enemy that was already three steps ahead.

Right: Unknown artist, “Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez,” unknown date. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Haussez writes that long before the Ordinances were published, “a meticulously coordinated plan of attack was conceived and communicated to the masses… weapons were gathered and distributed… [and] ammunition was stockpiled and converted into cartridges.” The scope of this revolutionary plot was so deep, he continues, that “the police should have uncovered some of its components.” The fact that they didn’t, Haussez says, is proof of incompetence or negligence.41

In fact, most historians looking at the July Revolution have concluded that, incompetent though the Restoration police may have been, there was a better reason they didn’t find proof of this revolutionary plot: it didn’t exist. Parisians took to the barricades spontaneously, not because they were ordered or paid to; the weapons used to fight Marmont’s army came from looted gun stores, not carefully laid stockpiles. And Charles and Polignac were genuinely unpopular, not merely victims of a conspiracy.42 Polignac’s careful bid for secrecy had indeed taken liberal leaders by surprise,43 but by the time he realized a grassroots uprising had taken place anyway, it was too late for precautions.

Jules de Polignac certainly believed in the Virgin Mary. But he had also believed that France was “a peaceful country devoted to its king.” July 1830 proved that wrong, as he lamented: “The evil that threatened France was, I must admit, deeper than I had imagined.” With that in mind, Polignac wrote fifteen years later, he should have recommended that Charles take extra precautions, like leaving Paris and issuing the Four Ordinances from a royalist part of France. Or at least, Polignac wrote, that’s what he would have done, “if the future had been suddenly revealed to me.”44

-

Or close enough, anyway. ↩

-

Matt. 1:20 (NRSV). ↩

-

For more on these doctrines and their history, see René Laurentin, A Short Treatise on the Virgin Mary, tr. Charles Neumann (Washington, New Jersey: AMI Press, 1991). ↩

-

Comtesse de Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne: 1820-1830, Vol. 3, ed. Charles Nicoullaud (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 302. Boigne and many other sources refer to Broglie-Revel as “the Comte de Broglie”; I am using his Broglie-Revel title in part to avoid confusion with his cousin, the much more prominent Duc de Broglie (who did publish memoirs). ↩

-

Pasquier writes about being in Paris during these events. Étienne-Denis, Duc de Pasquier, Mémoires du Chancelier Pasquier, vol. 6 (Paris: Librairie Plon), 252, 262, 265. ↩

-

Marthe Camille Bachasson, the Comte de Montalivet, writes in his memoirs that there was a widespread belief that Pasquier and Boigne had secretly married in England, a belief he personally shared. Pasquier, when asked about it, “showed himself more disposed to silence than to contradiction.” And anyway, Montalivet writes, “during the latter part of his life, Duc Pasquier lived with the Countess de Boigne in the sweetest and most constant intimacy.” Comte de Montalivet, Fragments et Souvenirs, vol. 2 (Paris: Calmann Lévy, Éditeur, 1900), 18n1. Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 271, 286, 301, 312. ↩

-

Pierre Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, ministre de Charles X: Sa vie de 1829 à 1847, Kindle Edition, 107. ↩

-

Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, 109. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, April 1, 1876. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, 109. ↩

-

Baron d’Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, Dernier Ministre de la Marine sous la Restauration, vol. 2 (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1897), 241-2. ↩

-

Auguste Jal, Souvenirs d’un Homme de Lettres (Paris: Léon Techener, 1877), 56-7. ↩

-

Jal, Souvenirs, 57. American author James Fenimore Cooper briefly visited Mirbel’s salon circa late 1827. He describes seeing a party around a card table “in which are three dukes of the vieille cour [old court], with M. de Duras at their head! The rest of the company was a little more mixed, but, on the whole, it savoured strongly of Coblentz and the emigration.” James Fenimore Cooper, Gleanings in France (New York: Oxford University Press, American Branch, 1828), 308. See also Comtesse de Bassanville, Les Salons d’Autrefois: Souvenirs Intimes, vol. 2 (Paris: Librairie H. Aniéré, 1862). ↩

-

Philip Mansel, The Court of France: 1789-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 170. Charles Caleb Colton, Narrative of the French Revolution in 1830 (Paris: A. and W. Gagliani; London: R. Kennett, 1830), 214. ↩

-

Berryer and Fitz-James were both active in a conspiracy to overthrow the July Monarchy and restore the Bourbons to the throne. Paul F.S. Dermoncourt, The Rebellious Duchess: The Adventures of the Duchess de Berri and her Attempt to Overthrow French Monarchy, 67-8. Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 4, 40. ↩

-

Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 1, 174. ↩

-

Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, 110. ↩

-

Comte Martial de Guernon-Ranville, Journal d’un Ministre: Oeuvre Posthume du Comte de Guernon-Ranville […], second edition (Caen: Le Blanc-Hardel, 1874), 72-3. Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 147. ↩

-

Except the War Minister, Louis-Auguste de Bourmont, who was still in Algiers with his army. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 11, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 341-2. ↩

-

Laurentin, A Short Treatise on the Virgin Mary, 126-35. ↩

-

Abbé Omer Englebert, Catherine Labouré and the Modern Apparitions of Our Lady: The Miraculous Medal… Prelude to a Century of Miracles, tr. Alastair Guinan (New York: P.J. Kenedy & Sons, 1958), 24-35. ↩

-

Englebert, Catherine Labouré, 36-39. ↩

-

Thomas Kselman, Conscience and Conversion: Religious Liberty in Post-Revolutionary France (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018) 9. ↩

-

Sandra L. Zimdars-Swartz, Encountering Mary: From La Salette to Medjugorje (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press), 27-57. ↩

-

Kselman, Conscience and Conversion, 81. Zimdars-Swartz, Encountering Mary, 27-57. Englebert, Catherine Labouré, 46-61. Labouré was not one of the 48 witnesses; she declined to speak to the vicar general and doggedly preserved her anonymity for many years. ↩

-

One point of similarity between Labouré’s account and the stories about Polignac is that both make the Virgin Mary out to be a Legitimist, a supporter of the traditional Bourbon monarchs of France. The stories about Polignac’s visions depict Mary giving advice about how he could defeat the enemies of the Bourbon throne and promising divine assistance in this quest — though this advice is never reported to be anything other than to stand fast, advice that if real does not seem to have been terribly effective. More interestingly, Labouré would decades later ascribe Legitimist sentiments to Mary in her visions. In an 1856 account, Labouré wrote that of the initial July 18 apparition, “The Blessed Virgin spoke to me of the manner in which I ought to be have toward my director and she also confided to me some things which I may not reveal.” But 20 years after that, in 1876 — 46 years after the visions — Labouré said that Mary had given her permission to reveal what she told her, that: “Great misfortune will come to France: her throne will be overthrown!” And that: “it will be thought that all is lost when the misfortunes (of which I tell you) begin to occur… There will be victims among the clergy of Paris. The archbishop himself will die… The Cross will be insulted, blood will flow in the streets.” Labouré said that she asked when these evils would happen, and was told, “In forty years.” This 1876 account of Labouré’s 1830 vision matches up with the events of the 1871 Paris Commune, a left-wing revolution in which Archbishop Georges Darboy was executed by the rebels, and thousands died in the “Bloody Week” of fighting that saw the Commune defeated. How much credence we should give this post-facto prophecy is up to the reader. Englebert, Catherine Labouré, 26-29. ↩

-

Laurentin, A Short Treatise on the Virgin Mary, 126-36. Thomas Kselman, Miracles and Prophecies in Nineteenth-Century France (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1983), 92-4. ↩

-

Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, 111. ↩

-

Jules de Polignac, Études Historiques, Politiques et Morales […] (Paris: Dentu, 1845), 23. ↩

-

Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, 110. ↩

-

Robin-Harmel, Le prince Jules de Polignac, 113. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 374. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 146-7. ↩

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 74. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 45. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 235-6. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 83-4. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 79-80, 89. ↩