Supplemental 7: Memorial of St. Helena

This is The Siècle, Supplemental 7: Memorial of St. Helena.

“It is my intention,” wrote Emmanuel de Las Cases, “to record daily all that the Emperor Napoleon did or said while I was about his person.” And so Las Cases did, in the form of his 1823 book, Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène, or The Memorial of Saint Helena. It was immediately a best-seller in multiple languages, and along with several other memoirs written by Napoleon’s aides in his St. Helena exile, helped transform the former emperor’s public image. It was, historian Philip Dwyer writes, “probably the most widely read political text of its time,” and became “the nineteenth-century Bonapartist bible.”1

Today, we’re going to be visiting that Bonapartist bible, in large part because the episode I was planning to release, Episode 21, isn’t quite done yet. But since Episode 20 covered the death of Napoleon, and Episode 21 will cover Napoleon’s legacy in Restoration France, it made perfect sense to tide you over with an excerpt from a memoir drafted on St. Helena, published in Paris in 1823, and instrumental in shaping the public view of Napoleon.

Las Cases, who turned 49 three days after Waterloo, was a curious fellow — an old regime noble who had emigrated during the Revolution and fought as a counter-revolutionary, before returning to France and very belatedly joining Napoleon’s regime. After the Hundred Days, he voluntarily followed Napoleon into exile, from a combination of devotion and ambition.2 On St. Helena, he was one of several aides who took dictation from Napoleon, though he was on the island for less than two years, and was not around for the emperor’s slow decline and death.

The Memorial was written by Las Cases as a diary, though large portions of the work consist of extended quotations from Napoleon. Or at least, supposed quotations from Napoleon. Though accepted as authentic by Bonapartists, the work had been revised first by Napoleon, then by Las Cases with assistance from a number of other French Bonapartists in the early 1820s. As Dwyer writes, Las Cases “significantly changed the content, rearranging conversations, suppressing passages and imbuing Napoleon with a rhetorical flair he never possessed.” Las Cases also regularly inserts himself into the work, and routinely uses the memoir to promote a historical atlas he had also written.3 It has a ramshackle but successful narrative structure, flip-flopping between the emperor’s recollections of grand battles or analyses of history, and discussions of the most mundane details of Napoleon’s exile on St. Helena.

The passages I’ve abridged to read to you here come entirely from the first volume of the book, and cover Napoleon’s first few months on St. Helena — his arrival on the island, his transfer to his prison estate of Longwood, and Napoleon’s pontifications about his rule and historical generals.

You will also note the myth-making in progress, as Las Cases at every turn plays up Napoleon’s genius, his suffering, his virtue, and other characteristics. There’s some truth to much of it — but the overall picture should reinforce how this book helped write the so-called “golden legend” that I talked about in Episode 20.

At thesiecle.com/supplemental7, you can see a transcript, as well as a link to the full text online at Project Gutenberg. This particular edition was an English translation published in 1836 by Henry Colburn and Company, with an uncredited translator.

My thanks for your forbearance as I prepare the next episode of the show, which will be ready hopefully very soon. Our excerpts begin as Napoleon and our narrator, Las Cases, approach Saint Helena on board the HMS Northumberland.

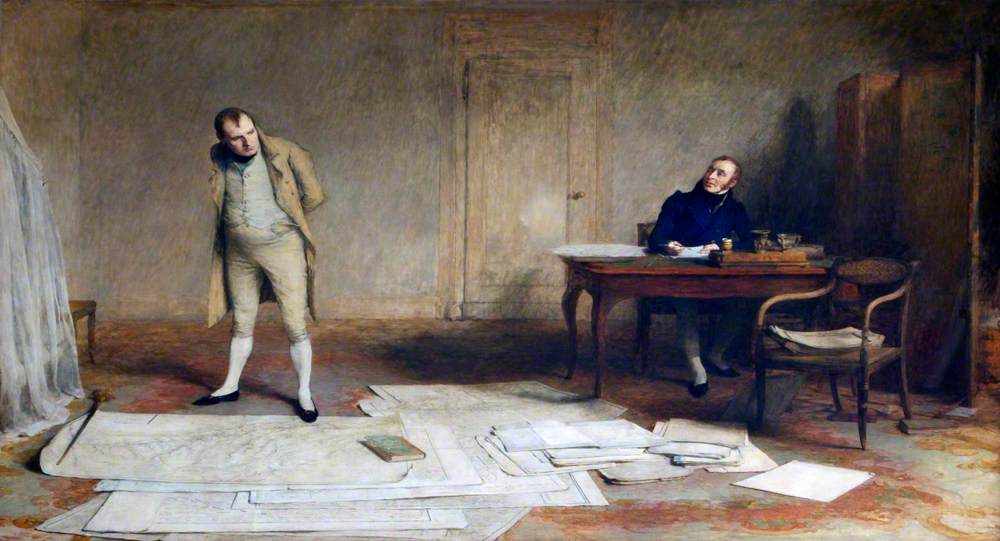

William Quiller Orchardson, “St. Helena 1816: Napoleon dictating to Count Las Cases the Account of his Campaigns,” 19th Century. Emmanuel-Augustin-Dieudonné-Joseph, comte de Las Cases, accompanied Napoleon to St. Helena and wrote the most famous memoir from the island, the “Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène” or “Memorial of St. Helena.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[Oct.] 15th. [1815]—At day light I had a tolerably near view of the island. At first I thought it rather extensive; but it seemed to diminish considerably as we approached. At length, about seventy days after our departure from England, and a hundred and ten after our departure from Paris, we cast anchor about noon. This was the first link of the chain that was to bind the modern Prometheus to his rock…

The Emperor, contrary to custom, dressed early and went upon deck; he went forward on the gangway to view the island. We beheld a kind of village surrounded by numerous barren and naked hills towering to the clouds. Every platform, every aperture, the brow of every hill, was planted with cannon. The Emperor viewed the prospect through his glass. I stood behind him. My eyes were constantly fixed on his countenance, in which I could perceive no change; and yet he saw before him, perhaps his perpetual prison!—perhaps his grave!… What, then, remained for me to feel or to express!

The Emperor soon left the deck. He desired me to come to him, and we proceeded with our usual occupation.

The admiral, who had gone ashore very early, returned about six o’clock, much fatigued. He had been walking about various parts of the island, and at length thought he had found a habitation that would suit us. The place, however, stood in need of repairs which might occupy two months. We had now been confined to our wooden dungeon for nearly three months; and the precise instructions of the Ministers were that we should be detained there until our prison on shore was ready for our reception. The Admiral, to do him justice, was incapable of such barbarity; he informed us, at the same time betraying a sort of inward satisfaction, that he would take upon himself the responsibility of putting us ashore next day.

[Nov.] 6th.—Among the various subjects of the day’s conversation, I note down what the Emperor said respecting the armies of the Ancients. He asked whether the accounts of the great armies mentioned in history were to be credited. He was of opinion that those statements were false and absurd. He placed no faith in the descriptions of the innumerable armies of the Carthaginians in Sicily. “Such a multitude of troops,” he observed, “would have been useless in so inconsiderable an enterprise; and if Carthage could have assembled such a force, a still greater one would have been raised in Hannibal’s expedition, which was of much greater importance, but in which not more than forty or fifty thousand men were employed.” He did not believe the accounts of the millions of men composing the forces of Darius and Xerxes, which might have covered all Greece, and which would doubtless have been subdivided into a multitude of partial armies. He even doubted the whole of that brilliant period of Greek history; and he regarded the famous Persian war only as a series of those undecided actions, in which each party claims the victory. Xerxes returned triumphant, after taking, burning, and destroying Athens; and the Greeks exulted in their victory, because they had not surrendered at Salamis. “With regard to the pompous accounts of the conquests of the Greeks, and the defeat of their numberless enemies, it must be recollected,” observed the Emperor, “that the Greeks, who wrote them, were a vain and hyperbolical people; and that no Persian chronicle has ever been produced to set our judgment right by contrary statements.”

But the Emperor attached credit to Roman history, if not in its details, at least in its results; because these were facts as clear as day-light. He also believed the descriptions of the armies of Gengiskan and Tamerlane, however numerous they are said to have been; because they were followed by gregarious nations, who, on their part, were joined by other wandering tribes as they advanced; “and it is not impossible,” observed the Emperor, “that Europe may one day end thus. The revolution produced by the Huns, the cause of which is unknown, because the tract is lost in the desert, may at a future period be renewed.”

The situation of Russia is admirably calculated to assist her in bringing about such a catastrophe. She may collect at will numberless auxiliaries, and scatter them over Europe. The wandering tribes of the north will be the better disposed and the more impatient to engage in such enterprises, in proportion as their imaginations have been fired, and their avarice excited, by the successes of those of their countrymen who lately visited us.

The conversation next turned on conquests and conquerors; and the Emperor observed that, to be a successful conqueror, it was necessary to be ferocious, and that, if he had been such, he might have conquered the world. I presumed to dissent from this opinion, which was doubtless expressed in a moment of vexation. I represented that he, Napoleon, was precisely a proof of the contrary; that he had not been ferocious, and yet had conquered the world; and that, with the manners of modern times, ferocity would certainly never have raised him to so high a point…

[Nov.] 25th.—The Emperor still continued unwell: he had passed a bad night. At his desire I dined with him beside the sofa, which he was unable to leave. He was, however, evidently much better. After dinner he wished to read. He had a heap of books scattered around him on the sofa. The rapidity of his imagination, the fatigue of dwelling always on the same subject, or of reading what he already knew, caused him to take up and throw down the books one after the other. At length he fixed on Racine’s Iphigenia, and amused himself by pointing out the beauties, and discussing the few faults, to be found in that work…

Contrary to the general opinion, in which I myself once participated, the Emperor is far from possessing a strong constitution. His limbs are large, but his fibres are relaxed. With a very expanded chest, he is constantly labouring under the effects of cold. His body is subject to the influence of the slightest accidents. The smell of paint is sufficient to make him ill; certain dishes, or the slightest degree of damp, immediately take a severe effect on him. His body is far from being a body of iron, as is generally supposed: all his strength is in his mind. His prodigious exertions abroad and his incessant labours at home are known to every one.

I have known the Emperor to be engaged in business in the Council of State for eight or nine hours successively, and afterwards rise with his ideas as clear as when he sat down. I have seen him at St. Helena peruse books for ten or twelve hours in succession, on the most abstruse subjects, without appearing in the least fatigued. He has suffered, unmoved, the greatest shocks that ever man experienced. On his return from Moscow or Leipsic, after he had communicated the disastrous event in the Council of State, he said:—“It has been reported in Paris that this misfortune turned my hair grey; but you see it is not so (pointing to his head); and I hope I shall be able to support many other reverses.” But these prodigious exertions are made only, as it were, in despite of his physical powers, which never appear less susceptible than when his mind is in full activity.

The Emperor eats very irregularly, but generally very little. He often says that a man may hurt himself by eating too much, but never by eating too little. He will remain four-and-twenty hours without eating, only to get an appetite for the ensuing day. But if he eats little, he drinks still less. A single glass of Madeira or Champaign is sufficient to restore his strength, and to produce cheerfulness of spirits. He sleeps very little and very irregularly, generally rising at daybreak to read or write, and afterwards lying down to sleep again.

The Emperor has no faith in medicine, and never takes any. He had adopted a peculiar mode of treatment for himself. Whenever he found himself unwell, his plan was to run into an extreme, the opposite of what happened to be his habit at the time. This he calls restoring the equilibrium of nature. If, for instance, he had been inactive for a length of time, he would suddenly ride about sixty miles, or hunt for a whole day. If, on the contrary, he had been harassed by great fatigues, he would resign himself to a state of absolute rest for twenty-four hours. These unexpected shocks infallibly brought about an internal crisis, and instantly produced the desired effect: this remedy, he observed, never failed.

The Emperor’s lymphatic system is deranged, and his blood circulates with difficulty. Nature, he said, had endowed him with two important advantages: the one was the power of sleeping whenever he needed repose, at any hour, and in any place; another was that he was incapable of committing any injurious excess either in eating or drinking. “If,” said he, “I go the least beyond my mark, my stomach instantly revolts.”

[Dec.] 4th—5th. For some time past a sensible change had taken place in the weather. We knew nothing about the order of the seasons. As the sun passed twice over our heads in the course of the last year, we said we ought, at least, to have two summers. Every thing was totally different from what we had been accustomed to; and, to complete our embarrassments, we were obliged, being now in the southern hemisphere, to make all our calculations in a manner quite the reverse of that which we had practised in Europe. It rained frequently, the air was very damp, and it grew colder than before. The Emperor could no longer go out in the evening; he was continually catching cold and did not sleep well. He was obliged to give up taking his meals beneath the tent, and he had them served up in his own chamber. Here he found himself better; but he could not stir from his seat.

The conversation then turned on war and great commanders. “The fate of a battle,” observed the Emperor, “is the result of a moment—of a thought: the hostile forces advance with various combinations, they attack each other and fight for a certain time; the critical moment arrives, a mental flash decides, and the least reserve accomplishes the object.” He spoke of Lützen, Bautzen, &c.; and afterwards, alluding to Waterloo, he said, that had he followed up the idea of turning the enemy’s right, he should easily have succeeded; he, however, preferred piercing the centre, and separating the two armies. But all was fatal in that engagement; it even assumed the appearance of absurdity: nevertheless, he ought to have gained the victory. Never had any of his battles presented less doubt to his mind; nor could he now account for what had happened. Grouchy, he said, had lost himself; Ney appeared bewildered…; d’Erlon was useless; in short, the generals were no longer themselves. If, in the evening, he had been aware of Grouchy’s position, and could have thrown himself upon it, he might, in the morning, with the help of that fine reserve, have repaired his ill success, and perhaps, even have destroyed the allied forces by one of those miracles, those turns of Fortune, which were familiar to him, and which would have surprised no one. But he knew nothing of Grouchy; and besides, it was not easy to act with decision amongst the wrecks of the army. It would be difficult to imagine the condition of the French army on that disastrous night; it was a torrent dislodged from its bed, sweeping away every thing in its course.

Turning to another subject, he said that the dangers incurred by the military commanders of antiquity were not to be compared with those which attend the generals of modern times. There is, he observed, no position in which a general may not now be reached by artillery; but anciently a general ran no risk, except when he himself charged, which Cæsar did only twice or thrice.

“We rarely,” said he, “find, combined together, all the qualities necessary to constitute a great general. The object most desirable is that a man’s judgment should be in equilibrium with his personal courage; that raises him at once above the common level.” This is what the Emperor termed being well squared…

“If,” continued he, “courage be a general’s predominating quality, he will rashly embark in enterprises above his conceptions; and, on the other hand, he will not venture to carry his ideas into effect, if his character or courage be inferior to his judgment.”

Physical and moral courage then became the subject of discourse. “With respect to physical courage,” the Emperor said, “it was impossible for Murat and Ney not to be brave, but no men ever possessed less judgment; the former in particular. As to moral courage,” observed he, “I have very rarely met with the two o’clock in the morning courage. I mean, unprepared courage, that which is necessary on an unexpected occasion, and which, in spite of the most unforeseen events, leaves full freedom of judgment and decision.” He did not hesitate to declare that he was himself eminently gifted with this two o’clock in the morning courage, and that, in this respect, he had met with but few persons who were at all equal to him. He remarked that an incorrect idea was generally formed of the strength of mind necessary to engage in one of those great battles on which depends the fate of an army or nation, or the possession of a throne. “Generals,” added he, “are rarely found eager to give battle; they choose their positions; establish themselves; consider their combinations; but then commences their indecision: nothing is so difficult, and at the same time so important, as to know when to decide.”

[Dec.] 11th—14th. We now found unfolded to us a new portion of our existence on the wretched rock of St. Helena. We were settled in our new abode, and the limits of our prison were marked out.

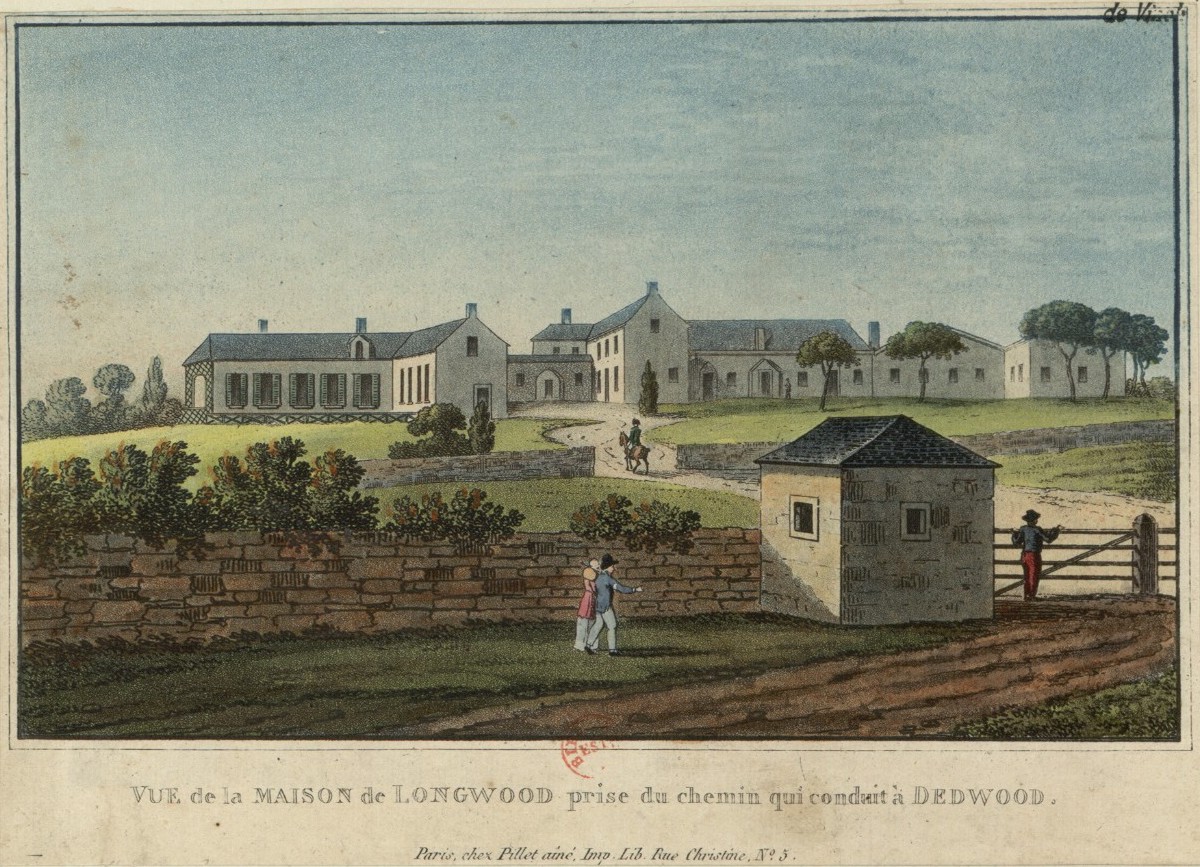

Longwood, which was originally merely a farm-house belonging to the East India Company, and which was afterwards given as a country residence to the Deputy Governor, is situated on one of the highest parts of the Island. The difference of the temperature between this place and the valley where we landed is marked by a variation of at least ten degrees of the English thermometer. Longwood stands on a level height, which is tolerably extensive on the eastern side, and pretty near the coast. Continual and frequently violent gales, always blowing in the same quarter, sweep the surface of the ground. The sun, though it rarely appears, nevertheless exercises its influence on the atmosphere, which is apt to produce disorders of the liver, if due precaution be not observed. Heavy and sudden falls of rain complete the impossibility of distinguishing any regular season. But there is no regular course of seasons at Longwood. The whole year presents a continuance of wind, clouds, and rain; and the temperature is of that mild and monotonous kind which, perhaps, after all, is rather conducive to ennui than disease. Notwithstanding the abundant rains, the grass rapidly disappears, being either nipped by the wind or withered by the heat. The water, which is conveyed hither by a conduit, is so unwholesome that the Deputy Governor, when he lived at Longwood, never suffered it to be used in his family until it had been boiled; and we are obliged to do the same. The trees, which, at a distance, impart a smiling aspect to the scene, are merely gum trees—a wretched kind of shrub, affording no shade. On one side the horizon is bounded by the vast ocean; but the rest of the scene presents only a mass of huge barren rocks, deep gulfs, and desolate valleys; and, in the distance, appears the green and misty chain of mountains, above which towers Diana’s Peak. In short, Longwood can be pleasing only after the fatigues of a long voyage, when the sight of any land is a cheering prospect. Arriving at St. Helena on a fine day, the traveller may, perhaps, be struck with the singularity of the objects which suddenly present themselves, and exclaim “How beautiful!” but his visit is momentary; and what pain does not his hasty admiration cause to the unhappy captives who are doomed to pass their lives at St. Helena!

Anonymous, “Vue de la Maison de Longwood prise du chemin qui conduit à Dedwood” (View of the House of Longwood from the path to Deadwood). Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Workmen had been constantly employed for two months in preparing Longwood for our reception; the result of their labours, however, amounted to little. The entrance to the house was by a room which had just been built, and which was intended to answer the double purpose of an ante-chamber and a dining room. This apartment led to another, which was made the drawing room; beyond this was a third room running in a cross direction and very dark. This was intended to be the depository of the Emperor’s maps and books; but it was afterwards converted into the dining room. The Emperor’s chamber opened into this apartment on the right-hand side. This chamber was divided into two equal parts, forming the Emperor’s cabinet and sleeping room: a little external gallery served for a bathing-room… Our windows and beds were without curtains. The few articles of furniture which were in our apartments had evidently been obtained from the inhabitants of the island, who doubtless readily seized the opportunity of disposing of them to advantage for the sake of supplying themselves with better.

[Dec.] 24th.—The Emperor had been reading some publication in which he was made to speak in too amiable a strain; and he could not help exclaiming against the mistake of the writer. “How could they put these words into my mouth?” said he. “This is too tender, too sentimental, for me: every one knows that I do not express myself in that way.” “Sire,” I replied, “it was done with a good intention; the thing is innocent in itself, and may have produced a good effect. That reputation for amiableness, which you seem to despise, might have exercised great influence over public opinion; it might at least have counteracted the effect of the colouring in which a certain European system has falsely exhibited your Majesty to the world. Your heart, with which I am now acquainted, is certainly as good as that of Henri IV., which I did not know. Now, his amiableness of character is still proverbial: he is still held up as an idol; yet I suspect Henri IV. was a bit of a quack. And why should your Majesty have disdained to be so? You have too great an aversion to that system. After all, quackery rules the world; and it is fortunate when it happens to be only innocent.”

The Emperor laughed at what he termed my prosing. “What,” said he, ”is the advantage of popularity and amiableness of character? Who possessed those qualities in a more eminent degree than the unfortunate Louis XVI? Yet what was his fate? His life was sacrificed!—No! a sovereign must serve his people with dignity, and not make it his chief study to please them. The best mode of winning their love is to secure their welfare. Nothing is more dangerous than for a sovereign to flatter his subjects: if they do not afterwards obtain every thing they want they become irritated, and fancy that promises have been broken; and if they are then resisted, their hatred increases in proportion as they consider themselves deceived. A sovereign’s first duty is doubtless to conform with the wishes of the people; but what the people say is scarcely ever what they wish: their desires and their wants cannot be learned from their own mouths so well as they are to be read in the heart of their prince.

“Each system may, no doubt, be maintained: that of mildness as well as that of severity. Each has its advantages and its disadvantages; for every thing is mutually balanced in this world. If you ask me what was the use of my severe forms and expressions, I shall answer, to spare me the pain of inflicting the punishment I threatened. What harm have I done after all? What blood have I shed? Who can boast that, had he been placed in my situation, he could have done better? What period of history, exhibiting any thing like the difficulties with which I was surrounded, presents such harmless results? What am I reproached with? My government archives and my private papers were seized; yet what has there been found to publish to the world? All sovereigns, situated as I was, amidst factions, disorders, and conspiracies, are surrounded by murders and executions! Yet, during my reign, what sudden tranquillity pervaded France!”

[Jan. 12th—14th.] Politics had also their turn. Every three or four weeks, or thereabouts, we received a large packet of journals from Europe; this, like the cut of a whip, set us going again for some days, during which we discussed, analyzed, and re-discussed the news: and afterwards fell again insensibly into our usual melancholy. The last journals had reached us by the Greyhound sloop, which had arrived some days before. They occupied one of the evenings, and gave rise to one of those moments, wherein that ardour and inspiration burst forth from the Emperor, which I have sometimes witnessed in the Council of State, and which escape him from time to time even here.

He took large strides as he walked amongst us, becoming gradually more animated, and only interrupting his discourse by a few moments of meditation.

“Poor France,” said he, “what will be thy lot! Above all, what is become of thy glory!…”

The papers seeming to say that England desired the dismemberment of France, but that Russia had opposed it, the Emperor said that he expected this; that it was natural that Russia should be dissatisfied at seeing France divided; because she would then have to fear that the different states of Germany would unite against her; whilst, on the other hand, the English aristocracy must be desirous of reducing France to the extremity of weakness, and of establishing despotism upon her ruins. “I know,” said he, “that this is not your opinion.” …I replied that it was very difficult to dispute with him; but that it appeared to me that in this same English aristocracy, it must be allowed, there might possibly exist heads sufficiently clear, as well as hearts just enough, to understand that, after having overthrown that which threatened their existence, it might prove advantageous to raise up that which was no longer to be dreaded; that circumstances were now singularly favourable for establishing a new system, which might for ever unite the two nations in their dearest interests, and render them necessary to each other, instead of keeping them in perpetual enmity, &c. The Emperor concluded the conversation by saying that he must be very perverse, without doubt; but that, with every consideration that he could give the subject, he could foresee nothing but catastrophes, massacres, and bloodshed.

Thank you again for continuing to listen to The Siècle. I’ve got lots of great episodes planned, including fascinating topics, interviews with preeminent scholars, and even a little semi-novel scholarship. My thanks also to all of you who have continued to support the show. The best way you can do that is to spread the word to your friends or followers, or to write reviews on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get the show. The reviews help attract new listeners for the show, and some of you have written some amazingly generous feedback, such as A.V. Buzzell, who called The Siècle “an amazing piece of historical research. Not only are the topics comprehensively covered, but each episode is published as a written transcript with footnotes on Montgomery’s website (thesiecle.com). It’s invaluable for anyone wanting to learn more or do their own research.”

Thank you so much, A.V., for those kind words. If you join A.V. in leaving your own review of the show, I might read it out loud in a future episode. I know you hear it in every podcast, but reviews really are vital for a show, especially a small, independent podcast like this one, which needs exposure to find an audience.

Please stay tuned to your feeds for The Siècle Episode 21: The Afterlife of Napoleon.