Episode 13: Bourbons, Neat

This is The Siècle, Episode 13: Bourbons, Neat.

My thanks to Sam from the Pax Britannica podcast for providing the promo for his show that you just heard. Pax Britannica is one of my favorite history podcasts, and I highly recommend you check it out.

Thanks also to you for your patience, as I failed to release any new episodes during the entire month of August. I was caught up in various work involving buying my first house and moving in — there are still so many boxes yet to unpack — but want to apologize for letting this podcast fall by the wayside.

This week on The Siècle, we’re going to take a step back to bring some important people out of the wings and into the limelight. I’m speaking about France’s royal family, the Bourbons, who I’ve mentioned in passing here and there but never talked about in detail, other than King Louis XVIII. In part that’s because I’ve been trying to not make this show a slog of names and dates, and in part it’s because many of these royals have in fact only played bit roles in the events so far. But others were right in the thick of things, and even the ones who weren’t were seen as extremely important by the people of their time. Think of the celebrity status of Britain’s royal family today — and then add genuine political influence to boot.

Also, spoiler alert: one of the royals I discuss in this week’s episode is going to die in Episode 14.

We’ve already talked quite a bit about Louis XVIII, including in Episode 12, my interview with Louis’s biographer, Philip Mansel. So we’re not going to spend much more time with the king today. Instead, it’s time to finally meet his family. Fair warning here: I’m about to drop a lot of names on you, and most of them are Louis. Call it an occupational hazard of French history.

Below: King Louis IX of France, in a detail from a larger image circa 1220-30. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Louis XVIII was a member of the House of Bourbon, one of the most illustrious noble houses of Europe. The house dates back to the Middle Ages, when a younger son of France’s famous King Louis IX — a famously devout crusader who was later canonized as St. Louis, the namesake of the American city — married the heiress to the Bourbonnais region of central France. The Bourbons thus trundled along as prominent French nobles for many centuries, until 1589, when King Henry III of France died childless. By the complicated rules of royal genealogy, the line of succession went all the way back up to Saint Louis, then down through his descendants, until it arrived at the 35-year-old Henri de Bourbon, then the king of a tiny, mountainous country on the border between France and Spain.1

Louis XVIII was a member of the House of Bourbon, one of the most illustrious noble houses of Europe. The house dates back to the Middle Ages, when a younger son of France’s famous King Louis IX — a famously devout crusader who was later canonized as St. Louis, the namesake of the American city — married the heiress to the Bourbonnais region of central France. The Bourbons thus trundled along as prominent French nobles for many centuries, until 1589, when King Henry III of France died childless. By the complicated rules of royal genealogy, the line of succession went all the way back up to Saint Louis, then down through his descendants, until it arrived at the 35-year-old Henri de Bourbon, then the king of a tiny, mountainous country on the border between France and Spain.1

Below: Henri IV, King of France and Navarre, circa 1600. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

There was just one minor little issue: Henri de Bourbon was a Protestant, and a militant Protestant at that, in a predominantly Catholic country that had been torn apart by the so-called Wars of Religion for decades. But Henry was a pragmatic fellow, and allegedly quipped, “Paris is well worth a mass.”2 He converted to Catholicism and took the French throne as King Henry IV, the first Bourbon king of France.

There was just one minor little issue: Henri de Bourbon was a Protestant, and a militant Protestant at that, in a predominantly Catholic country that had been torn apart by the so-called Wars of Religion for decades. But Henry was a pragmatic fellow, and allegedly quipped, “Paris is well worth a mass.”2 He converted to Catholicism and took the French throne as King Henry IV, the first Bourbon king of France.

Henry ruled for more than two decades, pursuing a policy of religious toleration that tried to end the country’s sectarian bloodshed. This massively annoyed critics on both sides, who tried a dozen times to assassinate him. The thirteenth time, however, was the charm, and Henry was stabbed to death by a radical Catholic in 1610.

We’re going to skip over the eventful reign of his son, Louis XIII, to get to the next person of immediate importance for our story: Henry’s grandson, the titanically important Louis XIV, the Sun King, whose epic 72-year reign saw France and the French monarchy transformed. You can learn more about Louis XIV in Philip Mansel’s new biography, King of the World: The Life of Louis XIV, a link for which is at thesiecle.com/episode13, but for our purposes I’m just going to focus on his family.

Below: Michel Corneille the Elder, “Philippe of France, Duke of Orléans (1640-1701) brother of Louis XIV, wearing armor with fleur-de-lys of the Sash of the Order of the Holy Spirit.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Louis XIV had a younger brother, Philippe, to whom he gave the title of “Duc d’Orléans.” Despite being openly homosexual, Philippe produced children with not one but two royal brides: Henrietta, the daughter of King Charles I of England, and Elizabeth Charlotte, the heir to the German territories of the Palatinate and great-granddaughter of King James I of England. If you want to learn about James, Charles, and their offspring, then you can do no better than to check out the Pax Britannica podcast.

Louis XIV had a younger brother, Philippe, to whom he gave the title of “Duc d’Orléans.” Despite being openly homosexual, Philippe produced children with not one but two royal brides: Henrietta, the daughter of King Charles I of England, and Elizabeth Charlotte, the heir to the German territories of the Palatinate and great-granddaughter of King James I of England. If you want to learn about James, Charles, and their offspring, then you can do no better than to check out the Pax Britannica podcast.

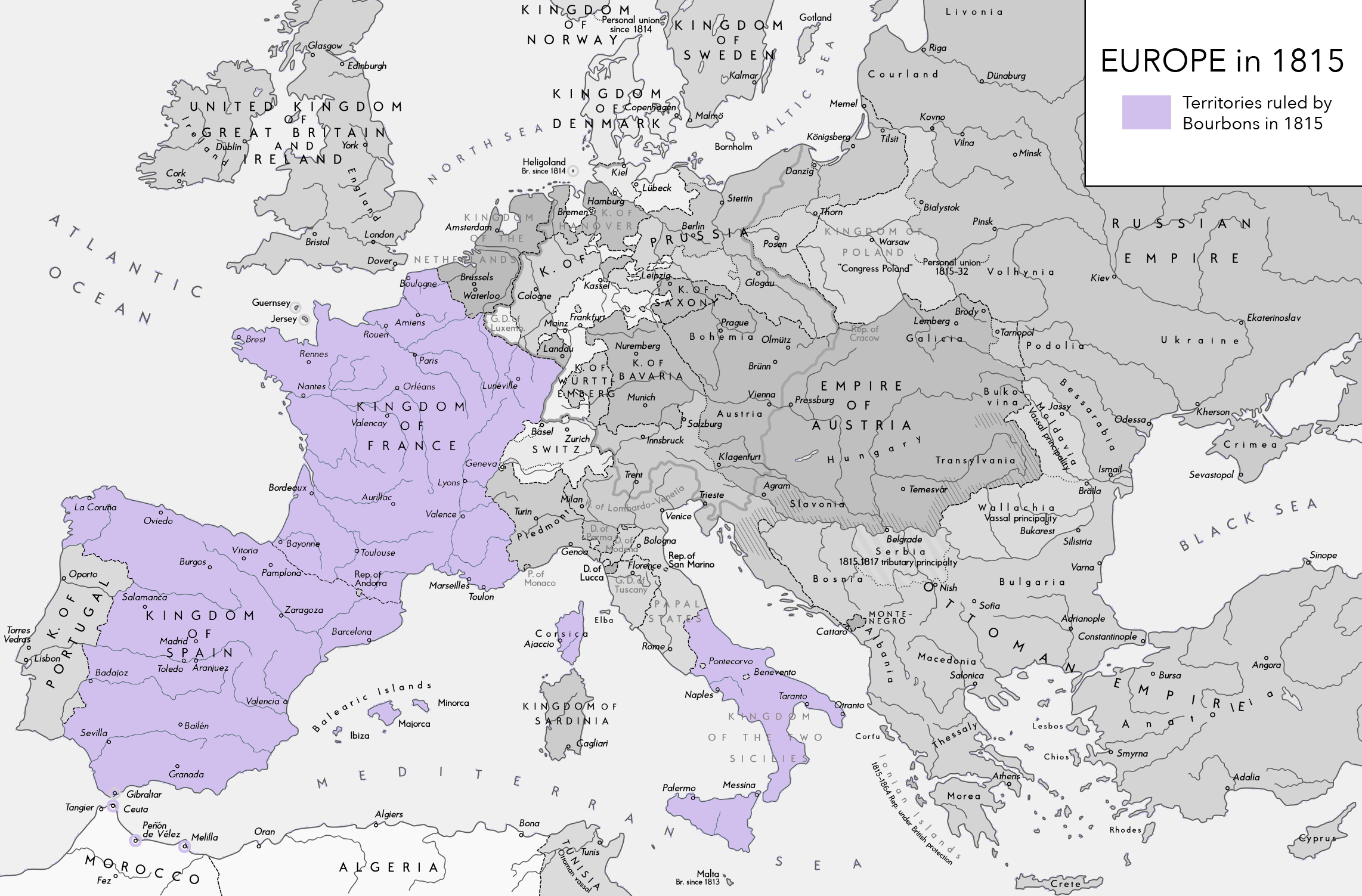

But Philippe’s sons and grandsons, despite their royal blood, would not rule France, though one of them would get the next-best thing as France’s regent for eight years. That’s because, among many bastards and children who died in infancy, Louis XIV had a legitimate son, who in turn had several children of his own. Two of the Sun King’s grandsons would become kings: one as King Louis XV of France, and another as King Philip V of Spain. This latter bit sparked a brutal continent-wide war3, and the upshot after all the killing was Philip was allowed to be King of Spain, but he had to renounce his claim on the Kingdom of France for himself and all his descendants. Thus Philip’s heirs branch off as the Spanish Bourbons. A generation later, the Spanish Bourbons will split again, with the King of Spain agreeing to give his Italian possessions away to one of his sons — the birth of yet another branch of the House of Bourbon, the so-called “Neapolitan Bourbons” who ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in southern Italy. And if you’re wondering why exactly there are two Sicilies, that’s a very interesting question based on more than 500 years of convoluted history, exactly none of which I’m going to get into in this podcast.

Territories ruled by branches of the House of Bourbon in 1815. Map by David Montgomery for The Siècle podcast, modified from original by Alexander Altenhof via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Instead we’ll come up to the eve of The Siècle’s setting. While two of Louis XIV’s grandsons became kings, Louis XV did him one better with three royal grandsons. The first was Louis-Auguste, who would rule France as Louis XVI from 1774 until his infamous date with a guillotine in 1792. The second was Louis Stanislas Xavier, who we know better as Louis XVIII, who claimed the French throne from the death of his nephew in 1795, and actually ruled starting in 1814. And the third was Charles Philippe, who at this time in our story is the heir presumptive to the French throne, and is known by his title, the Comte d’Artois, or simply as Artois.

I should clear something up that puzzled me when I first started doing research. When prominent French nobles are referred to as the “Comte d’Artois” or the “Duc d’Orléans,” that doesn’t mean they’re exercising any sort of feudal control over the regions of Artois or Orléans. That’s a medieval conception of lordship that just doesn’t apply in post-Revolutionary France. Some families might have ties to the regions in their titles, and might still own considerable land there, but that’s by no means always the case. And it’s especially not the case when we’re looking at members of the royal family, who are usually given courtesy titles as honors. As a comparison, think of the British royal family — the king or queen’s heir is traditionally made the Prince of Wales, but that doesn’t mean that he has any sort of political control over Wales.

The three royal brothers grew up together in Versailles, surrounded by wealth and opulence of a scale and nature almost inconceivable to modern minds. Mansel describes ancien régime Versailles as “at the same time a country house, an employment exchange, a riding school (the best in Europe), a bazaar, a casino, a government compound and a military headquarters, all on an enormous scale.” The palace was centered not on a throne room, as was traditional in many European courts, but on the king’s bedchamber, where there were elaborate ceremonies associated with the king’s rising each morning and going to bed each night. Nobles there wore fanciful, elaborate costumes, though by the 1780s these archetypical ancien régime court fashions were already somewhat passé in a Europe that had fallen in love with Prussian-style military uniforms.4

Artist unknown, the French royal family in 1782. Included are: at center, King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette hold their son, the heir to the throne who would later be dubbed King Louis XV by French royalists. Standing behind the king is his younger brother, the Comte de Provence, later King Louis XVIII. Standing at right is the Comte d’Artois, the youngest of the three royal brothers. In the rear at left are Artois’s young children, the Duc de Berry and the Duc d’Angoulême. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

All three royal children, dubbed “fils de France, or “Son of France,” were given a first-rate education for the day by a series of tutors. One anecdote from this childhood education perfectly captures the personalities of the three Bourbon children, all the way through to their future reigns. In their studies, the future Louis XVI “was best at science and mathematics”; the future Louis XVIII “was best at classics and literature,” and “as for Artois, he was almost always last.”5

Below: Henri-Pierre Danloux, “Charles Philippe de France, comte d’Artois,” 1798. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Artois may have been the worst at his studies, but he had other things going for him. Artois was handsome and outgoing, something of a playboy who frequently gets the label “debauched” attached to his younger days. As one historian put it, “The count’s intemperate drinking, addiction to gambling and mad pursuit of women shocked a Paris that had long been accustomed to such excesses.”6 Artois ran up massive debts of more than 21 million livres, including 2 million livres on a single chateau that Artois had built in just 63 days to win a bet with Queen Marie Antoinette, with whom he was quite close. (Artois was distinguished only by degree here — the future Louis XVIII also ran up millions of livres in debts during this period.)7

Artois may have been the worst at his studies, but he had other things going for him. Artois was handsome and outgoing, something of a playboy who frequently gets the label “debauched” attached to his younger days. As one historian put it, “The count’s intemperate drinking, addiction to gambling and mad pursuit of women shocked a Paris that had long been accustomed to such excesses.”6 Artois ran up massive debts of more than 21 million livres, including 2 million livres on a single chateau that Artois had built in just 63 days to win a bet with Queen Marie Antoinette, with whom he was quite close. (Artois was distinguished only by degree here — the future Louis XVIII also ran up millions of livres in debts during this period.)7

Most embarrassingly for his brothers, Artois was quite fertile, fathering two sons as well as a daughter who died young with his wife, an Italian princess — all born before the king and Marie Antoinette had any heirs of their own. The middle brother, Louis XVIII, would never have children, making Artois and his line the future of the dynasty by the time of the Restoration.

Even as a young playboy, Artois’s political instincts were quite conservative. In the run-up to the French Revolution, he opposed any concessions at all to the delegates of the “Third Estate,” the common people who were demanding a larger role in France’s future than the medieval laws of the Estates General gave them, at a time when his brother, the future Louis XVIII, was backing moderate concessions. Artois fled France for exile two days after the fall of the Bastille, among the first of what would eventually be a flood of aristocratic émigrés.8

Over the course of his long exile, much of which was spent in England, Artois underwent a significant change: the dissolute playboy of Versailles found religion — allegedly swearing a vow of chastity in 1804 after the death of his favorite mistress.9 With all the zeal of a convert, Artois would now combine his existing dedication to restoring the political old order with an equal commitment to France’s spiritual and moral rejuvenation.

The other important thing that happened to the Bourbon family during the princes’ exile was the family got smaller. King Louis XVI was executed in Paris, along with his wife Marie Antoinette. Royalists then recognized Louis’s young son as King Louis XVII, but the seven-year-old boy was currently in the hands of the revolutionaries. He was assigned to the custody of a cobbler with the mission of turning the boy into a republican citizen, and died a few years later at age 10 under still-murky circumstances. At this point Louis Stanislas Xavier, who fled the country himself in 1791, declared himself King Louis XVIII, and the Comte d’Artois became the heir presumptive to the throne. As the king’s oldest surviving brother, in the tradition of the French court, Artois was often referred to simply by the title “Monsieur.”10 After the Restoration, Artois lived in Paris, leading a social and political faction of conservative ultra-royalists from his residence at the Pavillon de Marsan, a wing of the Tuileries Palace. His household of courtiers, servants and hangers-on was more than 250 people, paid for by 8 million francs per year in taxpayer subsidies; the poet Lamartine wrote that Artois was “almost a king by the pomp of his household.”11 In 1814, Artois was 56, and unlike his massively obese brother, he was a “svelte, white-haired cavalier” with charming manners — an “affable, generous, benevolent gentilhomme”12, or gentleman. He was noted for being courteous even to his political enemies, and unfailingly polite.13

Below: François Kinson, “Louis-Antoine d’Artois, duc d’Angoulème,” circa 1815-1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Since the king was childless, that meant the line of Bourbon succession went through Artois’s two sons. The eldest, aged 39 in 1814, was Louis Antoine, dubbed the Duc d’Angoulême. History has not been kind to Angoulême, who gets described with words like “sickly,” “impotent” and “a blubbering nonentity.”14 This may be somewhat unfair, and definitely undersells Angoulême’s importance at the time, but it’s not necessarily wrong. Mansel describes him as “a much more forceful and impressive figure to the [French] court than he appears to posterity.”15 Notably, Angoulême had political opinions closer to his uncle, the king, than to his conservative father, was “committed” to the 1814 Charter and had “a reputation for disliking ultra-royalists and émigrés.”16 But much more so than any particular political opinions, what Angoulême was known for was his fickleness — he was “apt to change his mind rather quickly,” depending on who was influencing him at any given moment.17

Since the king was childless, that meant the line of Bourbon succession went through Artois’s two sons. The eldest, aged 39 in 1814, was Louis Antoine, dubbed the Duc d’Angoulême. History has not been kind to Angoulême, who gets described with words like “sickly,” “impotent” and “a blubbering nonentity.”14 This may be somewhat unfair, and definitely undersells Angoulême’s importance at the time, but it’s not necessarily wrong. Mansel describes him as “a much more forceful and impressive figure to the [French] court than he appears to posterity.”15 Notably, Angoulême had political opinions closer to his uncle, the king, than to his conservative father, was “committed” to the 1814 Charter and had “a reputation for disliking ultra-royalists and émigrés.”16 But much more so than any particular political opinions, what Angoulême was known for was his fickleness — he was “apt to change his mind rather quickly,” depending on who was influencing him at any given moment.17

Most importantly for the dynasty, Angoulême was also childless, and by 1814 it seemed clear he always would be. He had been married since 1799 and had no children either in or out of wedlock. But despite its barrenness, Angoulême’s marriage is important to our narrative, because his wife was a Bourbon herself: his first cousin, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, the 35-year-old daughter of Angoulême’s uncle Louis XVI. The Duchesse d’Angoulême had been a prisoner of the Revolution like her parents and brother, but had managed to survive until the Reign of Terror ended and she was exchanged for prisoners of the Allies. The experience seems to have left her understandably traumatized, and she would be noted as the most inflexible opponent in the royal family of liberalism and the legacy of the Revolution, “not by nature inclined to favor moderate solutions.”18 The Parisian bourgeois nicknamed her “Madame Rancune”, or “Lady Resentment,” for her undisguised “disdain for everything that recalled the Revolution or the Empire.”19

Most importantly for the dynasty, Angoulême was also childless, and by 1814 it seemed clear he always would be. He had been married since 1799 and had no children either in or out of wedlock. But despite its barrenness, Angoulême’s marriage is important to our narrative, because his wife was a Bourbon herself: his first cousin, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, the 35-year-old daughter of Angoulême’s uncle Louis XVI. The Duchesse d’Angoulême had been a prisoner of the Revolution like her parents and brother, but had managed to survive until the Reign of Terror ended and she was exchanged for prisoners of the Allies. The experience seems to have left her understandably traumatized, and she would be noted as the most inflexible opponent in the royal family of liberalism and the legacy of the Revolution, “not by nature inclined to favor moderate solutions.”18 The Parisian bourgeois nicknamed her “Madame Rancune”, or “Lady Resentment,” for her undisguised “disdain for everything that recalled the Revolution or the Empire.”19

Above: Antoine-Jean Gros, “Portrait of Marie Thérèse Charlotte of France, Duchesse d’Angoulême,” 1816. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In addition to the murder of her entire immediate family, the other source of sadness in the Duchess’s life was her childlessness, something both personally upsetting as well as with major dynastic implications. Mansel calls it “the tragedy of her life, which turned her into someone too often cold, sour and gloomy… And so in the dreary round of exile, never going to parties, never going to the theater, this charming princess lost her looks, her youth and all her joie de vivre.20

As an adult in the Restoration, the Duchesse d’Angoulême was noted for her severity in both politics and manner. She scorned the usual luxuries and social niceties expected of women of her era and station. In 1815, Louis attended a ball with his family, at which he “even made the Duchesse d’Angoulême put on rouge”21. But if she was lacking in the era’s expected feminine graces, she compensated in other areas. During Napoleon’s escape from Elba, when the Bourbon regime ineffectually tried to stop the emperor’s advance on Paris, most of the Bourbon royals fled ignominiously after half-hearted resistance, as I covered in Episodes 1 and 2. But the Duchesse d’Angoulême was an exception. In the city of Bordeaux, she marched straight into the barracks of a company of Bonapartist soldiers and tried to rally them to the Bourbon cause. When the emperor heard of her brave but futile stand, he reportedly quipped: “She is the only man in that family.”22 Later, after Waterloo, when Marshal Ney was condemned to death by treason — something I discussed in Episode 5 — Ney’s wife and supporters pleaded with the duchess to support clemency for the great marshal, on the theory that only she possessed both the influence and the unshakeable royalist credentials to win Ney a pardon. She refused.23

Below: Jean-Baptiste Jacques Augustin, “Portrait of Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry,” circa 1814-1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But Berry did have one thing going for him: though still unmarried at 36, Berry was very clearly fertile, as demonstrated by “a string of illegitimate children”27 — as many as 22, in some accounts, including two daughters by a British Protestant commoner named Amy Brown who unproven rumors allege Berry secretly married during his exile in London.28 These royal bastards were a mixed blessing for the dynasty — on the one hand proof that at least someone was capable of producing the next generation, but on the other hand the kind of bad behavior that made Europe’s crowned heads unwilling to give their daughters in marriage despite the probability that the union’s offspring would rule France.29 Getting Berry married was one of Louis XVIII’s top priorities in the first years of his reign.

Of course, it’s not fair to say that the fate of the French Bourbons rested entirely on the Duc de Berry. There was another branch of the family who could inherit the throne, who were clearly fertile and clearly available. I speak of the House of Orléans, descended from Louis XIV’s younger brother who I briefly introduced earlier, the Duc d’Orléans.

Below: Unknown artist after François Gérard, “Adélaïde d’Orléans,” circa 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1814, that branch of the Bourbon family was represented by the 40-year-old Louis-Philippe, the current Duc d’Orléans, as well as Louis-Philippe’s sister Adélaïde, an extremely intelligent woman who was Louis-Philippe’s intellectual and political partner — in one 1807 letter, the duke wrote that “if I wasn’t your brother, I would [marry you] straight away.”30 I’ll introduce the fascinating Adélaïde more fully in future episodes.

In 1814, that branch of the Bourbon family was represented by the 40-year-old Louis-Philippe, the current Duc d’Orléans, as well as Louis-Philippe’s sister Adélaïde, an extremely intelligent woman who was Louis-Philippe’s intellectual and political partner — in one 1807 letter, the duke wrote that “if I wasn’t your brother, I would [marry you] straight away.”30 I’ll introduce the fascinating Adélaïde more fully in future episodes.

We’ve discussed Louis-Philippe several times on the show, most notably in Episode 2, when he was mentioned as a possible replacement for Louis XVIII as the French king. Louis-Philippe had impeccable royal bloodlines, but his politics were decidedly more liberal than any of his cousins from the elder branch of the Bourbons — which was either a selling point or a black mark, depending on your politics. Louis-Philippe was also tarred by the actions of his father, the prior Duc d’Orléans, who had been an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, to the point that he eventually changed his name to “Philippe Égalité” and, as a member of the National Convention, voted to execute his cousin Louis XVI. While these actions may have been an attempt to protect himself and his family in the highly charged political atmosphere of 1793 Paris, they left a lasting black mark on the Orléans family in the eyes of the Bourbons and other European nobles, even though Philippe Égalité had met his own end at the Revolutionary guillotine not too long afterwards.31

Below: Louis-Joseph Noyal after François Gérard, “Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans, in the uniform of a Guard-Colonel of the Hussars,” circa 1817. Public domain via Wikipedia Commons.

Though by 1814 Louis-Philippe had submitted himself to his cousins and won a grudging re-acceptance, he was never fully welcomed back into the fold.32 Louis XVIII in particular seemed to hold a grudge against the Duc d’Orléans, as one example makes clear. The customs of the French court meant nobles were treated differently based on their social rank, and fine gradations were preserved even at the very apex. Louis-Philippe held the rank of “Serene Highness,” just one step below the highest rank of “Royal Highness.” Louis-Philippe very much wanted to be elevated to “Royal Highness,” and Louis XVIII just as resolutely refused to give the promotion. Petty? To be sure. But the slight meant a constant string of low-grade humiliations for Louis-Philippe, especially because his wife, the daughter of the King of Naples from the Neapolitan Bourbons, was a “Royal Highness.” That meant that when the Orléans family was presented at court, both doors would be opened for the Duchesse d’Orléans. The Duc d’Orléans was refused entry until one of the doors was shut in his face, because only “Royal Highnesses” were entitled to enter with both doors held open.33

Though by 1814 Louis-Philippe had submitted himself to his cousins and won a grudging re-acceptance, he was never fully welcomed back into the fold.32 Louis XVIII in particular seemed to hold a grudge against the Duc d’Orléans, as one example makes clear. The customs of the French court meant nobles were treated differently based on their social rank, and fine gradations were preserved even at the very apex. Louis-Philippe held the rank of “Serene Highness,” just one step below the highest rank of “Royal Highness.” Louis-Philippe very much wanted to be elevated to “Royal Highness,” and Louis XVIII just as resolutely refused to give the promotion. Petty? To be sure. But the slight meant a constant string of low-grade humiliations for Louis-Philippe, especially because his wife, the daughter of the King of Naples from the Neapolitan Bourbons, was a “Royal Highness.” That meant that when the Orléans family was presented at court, both doors would be opened for the Duchesse d’Orléans. The Duc d’Orléans was refused entry until one of the doors was shut in his face, because only “Royal Highnesses” were entitled to enter with both doors held open.33

Even beyond such snubs, the familial relationship between the elder branch of the Bourbons and their Orléans cousins was fraught, because everyone knew that the Duc d’Orléans wanted to be king. We are told of the extended Bourbon family gathering to celebrate Epiphany, when the traditional “king cake” would be baked with a bean hidden inside; whichever person got the slice of cake with the bean would crowned “king” of the celebration. The awkwardness of Louis-Philippe being crowned “king” at this farce, with his crowned cousin smirking across the table, was evident to all parties; after one such Epiphany when Orléans got the bean, the king wrote a snide letter mocking the duke’s sullen face: “Perhaps,” the king said, “he finds that this royalty does not amount to much.”34

Artist unknown. The French royal family, circa 1816-1820. From left: the Comte d’Artois, King Louis XVIII, the Duchesse de Berry, the Duchesse d’Angoulême, the Duc d’Angoulême and the Duc de Berry. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Still, despite only getting to be King of the Bean, Orléans lived a pretty good life. His marriage to Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily was happy and fecund; by Waterloo the Orléans had two daughters and two sons already, and the couple would ultimately have 10 children, eight of whom would survive to adulthood. With Berry still unmarried and lacking legitimate children, Louis-Philippe was in line for the French throne, behind the aged Artois, Angoulême and Berry. It seemed entirely possible that the House of Orléans would get to be kings for real one day.

Whether that day will come is a question we’ll have to get to later in our narrative. Until then, we’re going to see the various Bourbon royals in action in the next full episode of The Siècle. You’re also going to get a special bonus episode discussing some of the sources I’ve used to write the podcast, a bonus episode brought to you by the support of my backers on Patreon, including Chas S., Philip Pomerantz, Anthony Pitts, Robert Rosén, Richard Riley, Bret Matthew, Elliot Shank, Michael Jochum, M. Mocella, Jacob Nelson, Stephen Caruso, Steven Lubman and Douglas Hayes, who have all backed the show since I last thanked new patrons. Producing the show takes a lot of time and a surprising amount of money, and even a dollar or $5 per month can make a huge difference. You can find out more at patreon.com/thesiecle — that’s t-h-e-s-i-e-c-l-e, or at thesiecle.com/support. You can also visit thesiecle.com/episode13, with 13 as a numeral, to see the online version of this episode — a full transcript, with sources, footnotes, maps, and paintings of the various figures discussed here. It’s worth checking out for the picture of the Duc de Berry alone, who looked exactly like you’d expect him to look. That’s thesiecle.com/episode13. Also be sure to check out Sam Hume’s podcast, Pax Britannica.

That bonus episode might or might not end up being the next episode to hit your feeds, depending on my schedule over the next two weeks. In either case, the next regular episode of the show will revisit that dramatic development I teased at the beginning of this episode: one of the Bourbon royals I talked about today is about to die. Find out which one next time in The Siècle Episode 14: “Slipped on the Blood.”

-

Specifically, Navarre. ↩

-

There is no evidence that Henry actually said this phrase famously attributed to him, but it “accurately reflected Henry’s thinking.” Edmund H. Dickerman, “The Conversion of Henry IV: ‘Paris Is Well Worth a Mass’ in Psychological Perspective,” The Catholic Historical Review 63, no. 1 (1977), 1. ↩

-

The War of Spanish Succession. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 7-9. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 11. ↩

-

Vincent W. Beach, “The Count of Artois and the Coming of the French Revolution,” The Journal of Modern History, 30, no. 4 (Dec. 1958), 314. ↩

-

Antonia Fraser, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (New York: Anchor Books, 2001), 108, 150. ↩

-

Beach, “The Count of Artois,” 320, 324. ↩

-

Reportedly, the final exchange between the dying Louise de Polastron and her lover the Comte d’Artois involved her demanding: “‘Before I die, Monseigneur, I beg one last thing from you. Belong henceforward to God.’ ‘I swear it,’ answered Artois. ‘Only to God,’ Louise added painfully, ‘to God only.’” Regardless of whether or not this story is true, Artois was clearly quite devoted to her, and was visibly transformed by her death. Margery Weiner, The French Exiles: 1789-1815, (London: John Murray, 1960), 158-9. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 16. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, The Court of France: 1789-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 99-100, 179. Technically the 8 million franc subsidy also covered the households of Artois’s sons and their families, as well, though they were somewhat smaller. ↩

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 9. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 163. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 9. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 169. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 169. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 292 ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 232. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 10. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 105-6. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 219. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 230. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 326. ↩

-

Also sometimes spelled as “Berri.” ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 10. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 194. ↩

-

Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 13. ↩

-

Weiner, The French Exiles, 162-3. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 13. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 43-44. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 27-8, 34. As one example of the disgust Europe’s aristocracy had for Philippe Égalité’s regicide, we are told of the reaction of the British Prince of Wales, who had been friends with the duke before the Revolution, even commissioning a portrait of him. But upon hearing of the duke’s vote to kill the king, the Prince ordered the portrait removed, and had Orléans père expelled from a tony social club they both shared. To drive home his scorn, the prince had Orléans’ name scratched off the rolls by a mere waiter. Weiner, The French Exiles, 138. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 41-42. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 291. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 291-2. ↩