Episode 23: Charbonnerie

On Dec. 14, 1821, France’s Ultra-royalists took control of France’s government for the first time during the Bourbon Restoration, with the appointment of a ministry led by the Comte de Villèle. Almost immediately after this right-wing government took over, government officials began claiming to have uncovered liberal conspiracies in towns across the country, which necessitated the arrest of hostile members of the French army and implicated some of the most prominent opposition deputies in parliament.

For example, two students at a cavalry school along the Loire River claimed just before Christmas that agitators were trying to lead a national uprising to put Napoleon’s young son on the throne as Napoleon II.1 On New Year’s Day officials in an eastern town alleged that the Marquis de Lafayette was involved in an attempt to raise the garrison against the Bourbons.2. On Jan. 15, another supposed conspiracy was revealed by an informer, a Swiss immigrant who claimed to be intimately connected with the whole affair.3

Citing all these incidents, Ultra-royalists called for a national crackdown. The Vicomte de Bonald, a counter-revolutionary philosopher and lawmaker, rose in the Chamber of Deputies to demand that the government set aside legal niceties and start suppressing the enemies of the state:

We do not require of the government or of the courts the certainty that even God does not give us; but in the name of men of good will we all demand security; we demand that they repress at last… these factious declamations, these perfidious calumnies of which the criminal attempts renewed before our eyes are only the echo.

In response, a liberal deputy noted how perfectly convenient these supposed plots were for Ultra-royalists looking for a chance to attack their enemies in a repeat of the 1815 White Terror. “Who,” he asked, “credits these conspiracies… which always appear at the right moment for each violation of the Charter, each sacrifice of our liberties?”4

But the Ultras were entirely right. France’s liberals were plotting military coups to overthrow the government. The arrests so far included real conspirators. Political opponents like Lafayette were involved. So were high-ranking military officers. The plots were organized in secret societies, who aimed at nothing less than the overthrow of King Louis XVIII. These secret societies were inspired by a similar group that had been behind the 1820 liberal coup in Naples, who adopted the fiction that they were descended from humble charcoal-burners, or carbonari.5 In actuality, these Carbonari had nothing to do with charcoal, but under this name, they would shake the foundations of not just Italy, but France.

This is The Siècle, Episode 23: Charbonnerie.

Anatomy of a secret society

According to their initiation rites, the Carbonari were first founded in Ancient Egypt, or in the middle ages by the Knights Templar, or one of several other possibilities, depending on the source. According to actual historical fact, they were founded in the beginning of the 19th Century to resist the Napoleonic occupation of Italy. They were probably an offshoot of Freemasonry, which similarly combined secrecy, liberal ideas, and a healthy dose of mysticism, but the Carbonari had a more overtly political focus of insurrection. Initially aimed at the French, when Napoleon was defeated the Carbonari soon redirected themselves against Italy’s reactionary restored monarchies.6

Below: Guglielmo Pepe, a Neapolitan general and revolutionary leader of the Carbonari in the 1820 revolution. After it was defeated, he went into exile. Drawn by Gerolamo Tubino. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Italian Carbonari is largely beyond the scope of this podcast, except to note that its members were involved in the Italian revolutions of 1820, discussed in Episode 17 and Episode 18, which successfully brought liberal reform before being crushed by the Austrians.

The Italian Carbonari is largely beyond the scope of this podcast, except to note that its members were involved in the Italian revolutions of 1820, discussed in Episode 17 and Episode 18, which successfully brought liberal reform before being crushed by the Austrians.

What’s important here is that Carbonarism eventually spread to France. The vehicle for this was another important incident I covered in a past episode: the attempted military coup of August 1820, planned by liberals in the aftermath of the Law of the Double Vote and other “Exceptional Laws” I discussed in Episode 15. Believing their chances of winning power legally had been crushed by these new laws, liberals tried to organize a coup, but it was easily discovered and suppressed. Some of the organizers fled the country to escape the crackdown, and ended up taking refuge in Naples, where they encountered the Carbonari. In 1821, several of these activists returned to France and immediately began organizing their own conspiratory cells along Carbonari lines.7

So what were those Carbonari lines that French conspirators adopted for what they dubbed, in translation, the Charbonnerie? This is actually surprisingly hard to tell with any specificity. The Carbonari were a secret society who tried to keep their organization a secret, and also surrounded the practical details with a lot of mystical hocus-pocus for effect. Various claims about the Carbonari disagree, even from people we know for a fact were members. And it was a fairly decentralized organization that functioned differently in different places.8

In general, though, we can say that it was organized on a cell structure — small local groups of less than 20 people, which were called a vente — you can check out a footnote at thesiecle.com/episode23 to learn the needlessly complex reason why.9 Each cell, in theory, had just a single point of contact with other cells, so that if one cell were compromised, the damage to the movement as a whole could be contained. The cells were organized in a hierarchical structure, with a single haute vente or vente suprême ostensibly directing the entire conspiracy from Paris, local cells at the bottom, and regional ventes in between.10

In theory, the Charbonnerie was supposed to be bottom-up, with local cells organizing spontaneously and nominating delegates to regional cells, who in turn elected a vente suprême. In practice, things operated in reverse, with the central vente being organized first, and seeding out a range of local cells.11

But that’s not to say that everything was centrally directed. Despite the pretensions of its leaders, and the fears of its enemies, individual cells had quite a bit of autonomy. The members of the Charbonnerie agreed on little other than their distaste for the Bourbons — there were republicans and Bonapartists, idealists and schemers, bored soldiers and people nursing particular grudges. “To be honest,” one member recounted later, “the revolutionary party was a confused assemblage of patriots of every hue, and of malcontents.”12 Even among the centralized leaders of the vente suprême there were multiple factions, “each of which believed that it was manipulating the others.”13

At a practical level, membership in a Carbonari cell ostensibly brought with it a commitment to violent revolution, including a famous pledge that each member would acquire a rifle and 25 cartridges of ammunition for when the revolution came.14 Joining also had certain rituals, derived from the Italian Carbonari. The Italians, we are told, made initiates undergo a whole assortment of baroque rituals, including initiates being blindfolded, undergoing a symbolic journey through the woods, a mock recreated trial of Jesus Christ at the hands of Pontius Pilate, and an oath of loyalty to the Carbonari cause with death as the penalty for betrayal.15 The French Charbonnerie adopted some but not all of these rituals, notably dropping many of the Christian and Catholic trappings that the Italian order used. For example, where the Italians swore their loyalty to “the grand master of the universe and the glorious Saint Theobald,” the French Carbonari apparently made a statement of “fundamental principles” including “equality before the law, freedom of the press… and the promise never to usurp the sovereignty of the French people.”16 One thing the French definitely kept from the Italian Carbonari was the nomenclature: members in both countries referred to each other as “good cousins,” or “bons cousins” in French.

Age of secrets

This focus on ritual, conspiracy, and secret societies was a reflection of the age. As historian Robert Tombs writes, French political culture in the 19th Century had “a paranoid obsession with conspiracies, a lurid world inhabited not only by cranks and simpletons, but by serious and influential thinkers and statesmen.”17 The right saw conspiracies among freemasons and Protestants; the left in turn was obsessed with the idea of conspiracies by the Jesuits, a prominent Catholic religious order.

There were also rational reasons to expect your political enemies to be plotting in secret, rather than out in the open. This was still a period with censorship, limits on public association, and even a routine habit of secret police reading people’s mail.18

And the French didn’t merely obsess over their enemies’ alleged conspiracies and secret societies — they formed their own. Freemasonry, while never as ubiquitous or powerful as its opponents claimed, was still a real organization with codes of secrecy to which many left-leaning politicians belonged; while some masonic lodges were little more than social clubs, others were much more radical and political.19 The ultra-royalists in turn had the Chevaliers de la Foi, or Knights of the Faith, a royalist, Catholic imitation of freemasonry, who had plotted against Napoleon, and then again against moderates in Louis XVIII’s government.20 In 1818, when Louis was aligned against the ultras, there was a report of an alleged attempt by certain ultras, working with segments of the military and royal guard, to seize Louis and force him to appoint a more conservative cabinet, and maybe even kill him if he refused.21 This supposed right-wing conspiracy turned out to be little more than grumblings and gossip exaggerated by police agents trying to impress their superiors. But the idea was plausible — secret societies and conspiracies were in the air, on all sides.22

On top of all this, there were recent examples of conspiracies and coups that had demonstrably succeeded. We’ve already talked about the uprisings in Italy and Spain, in which junior officers taking decisive action had almost effortlessly collapsed unsteady regimes. And closer to home, there was of course the example of the Hundred Days, when Napoleon had been able to retake the government practically without firing a shot. To be sure, all these successful coups would later be crushed by foreign invasions. But liberals had plenty of examples to justify the belief that the Bourbon Restoration just needed a stiff push from the military and it would collapse, like it had in 1815, and like Bourbon kings in Spain and Naples had in 1820.

Let’s see how all this played out.

The plots

Carbonari agents fanned out across France in 1821, with the goal of finding new recruits to form new cells. This was before Villèle’s ultra-royalist government came to power in December 1821, but after the Bourbon regime had turned sharply to the right in 1820, as described in Episode 15.

Many of the recruiting agents were largely radical young men based in Paris, who had organized secret societies in the capital before trying to spread their movement to the rest of their country.23 And it’s no real wonder: while students and young people can be disproportionately radical in any age, the situation in the 1820s seemed particularly bleak for young people. For one thing, France itself was young — about 40 percent of the population was under 20 years old, and another quarter were between 20 and 40.24 Today, by contrast, the share of the French population over 40 has risen from about 33 percent in 1820 to about 53 percent.25

But while France was young, power was concentrated in the hands of the old. The Charter of 1814 set a strict age minimum of 40 to serve in the Chamber of Deputies, even if you were rich enough to do so; no one under 30 was allowed to vote. The share of departmental prefects who were over 50 was rising steadily, as the generation that had come of age around 1789 clung to power despite their advancing age. One pamphlet, called On Gerontocracy, or the Abuse of the Wisdom of Old Men in the Government of France, acidly characterized France’s ruling elite as “seven thousand or eight thousand asthmatic, gouty, paralytic” men, and attacked the fixation of both sides with “these ruins of a stormy age in the past.” As the historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny put it, “the youth of 1830 was therefore bulging with lawyers without cases, doctors without patients, sons of workers and peasants whose studies had incapacitated them for manual labor without opening the way to their preferred careers, bourgeois young men furious at having to mark time in waiting rooms or seeing themselves hopelessly relegated to subordinate administrative positions.”26 Is it any wonder many young men embraced the idea of violently overthrowing the state?

Other core Carbonari were former officers in Napoleon’s army, who had been sent home on half-pay as the Bourbons simultaneously cut expenses and tried to push out political opponents.27 These former officers were especially valuable for the Carbonari; not only did they possess knowledge of tactics and experience under fire, but they had connections with the conspirators’ most prized recruits: active-duty soldiers. Sometimes this involved actual relationships between the former and current soldiers, but even a shared background could be valuable: up to 75 percent of army officers were Napoleonic veterans, who often regaled their younger comrades-in-arms with stories of Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt, Italy and Russia. That made a vivid contrast to the dreary garrison life to which Restoration France’s peacetime army was largely consigned.28

So these young radicals and disgruntled veterans fanned out across much of the country, seeking out anyone who was disaffected with Louis XVIII’s regime to join their new secret society. In addition to active-duty soldiers, frequent targets for recruitment were middle-class professionals, land-owning peasants, and other young radicals and Napoleonic veterans.

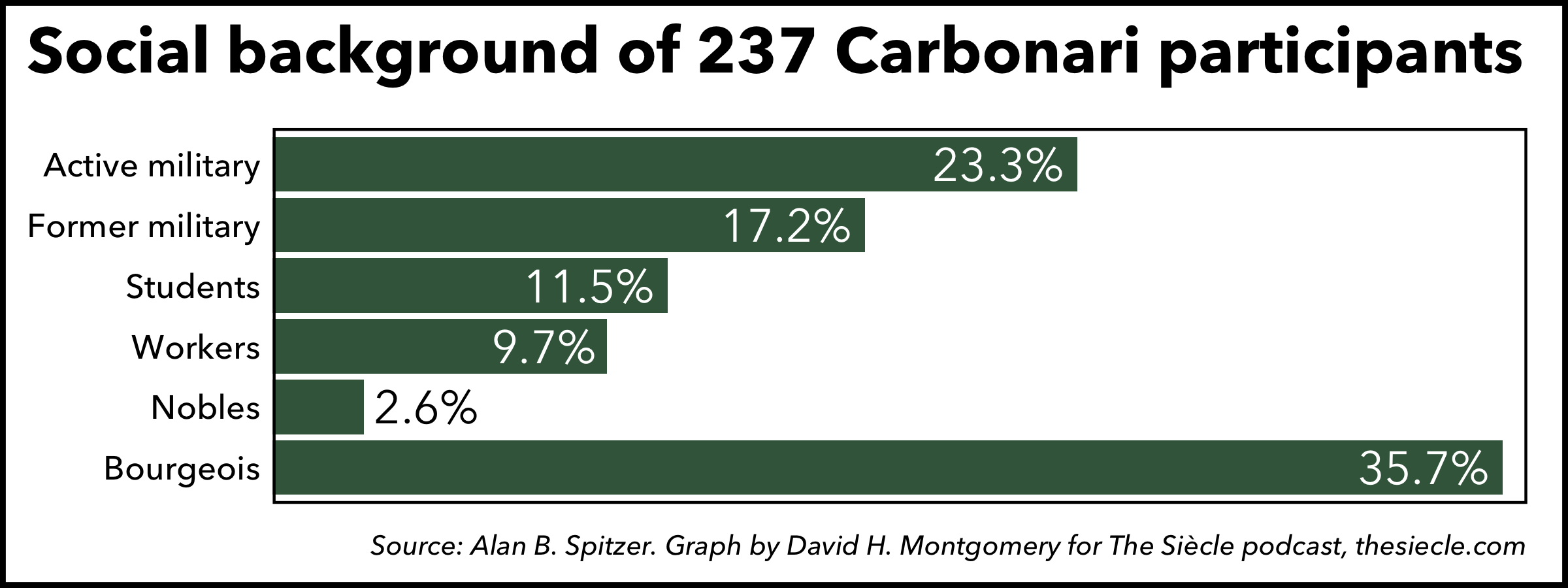

Historian Alan Spitzer compiled a list of 227 identified or presumed Carbonari members for whom occupations or social status could be determined. Of these 227, about 23 percent were active-duty military, and another 17 percent half-pay, inactive or former military. Another 36 percent or so had bourgeois professions — lawyers, doctors, journalists, business owners, retired public officials, and the like. The rest included about 11 percent who were students and 10 percent who were workers. There were also a handful of aristocrats, of whom the Marquis de Lafayette is an illustrative example.29 Of course, this is by definition unreliable — we know people were Carbonari because someone either got caught, or because they admitted to it later in life, so this is by no means a representative sample of the movement’s full membership.

In most of the areas where they would find the most success, they drew on pre-existing anti-Bourbon groups, such as the Chevaliers de Liberté or Knights of Liberty in the Loire Valley, or on the patronage networks of bourgeois mill owners in Alsace.30

However they recruited, sources agree that the Carbonari spread across France with spectacular speed in the latter half of 1821. Some panicky government officials guessed there were as many as 800,000 French Carbonari out of a total population of around 32 million; more recent scholarly guesses put the figure closer to 50,000 recruits. Government officials at the time also reported Carbonari activity in as many as 35 of France’s 86 departments, but this might reflect “only that some agent accused the local opposition of conspiring.” With somewhat more certainty, we can definitely say that the Carbonari were active in some two-dozen major communities around France, and some 15 to 20 military units.31

This spread was perhaps helped by another event that happened in 1821: the death of Napoleon Bonaparte, as covered in Episode 20. When news of the former emperor’s death reached France in July 1821, it put a damper on hopes that Napoleon might return again to claim the throne — though, as you might remember from Episode 21, it didn’t quash them entirely. With Napoleon dead, Bonapartists were liberated to be more flexible in their opposition politics, just at the time that the Carbonari were recruiting.32

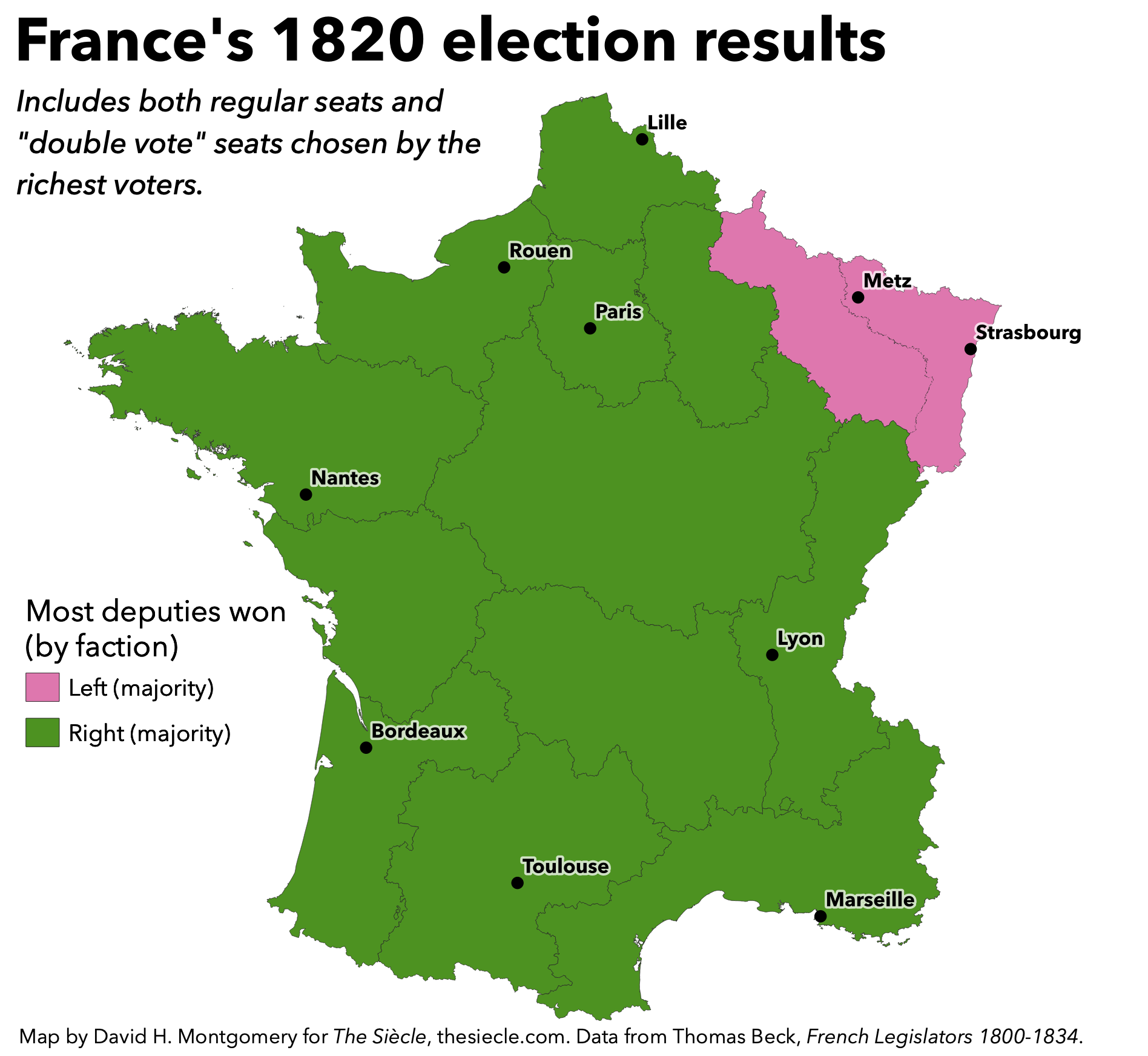

Belfort

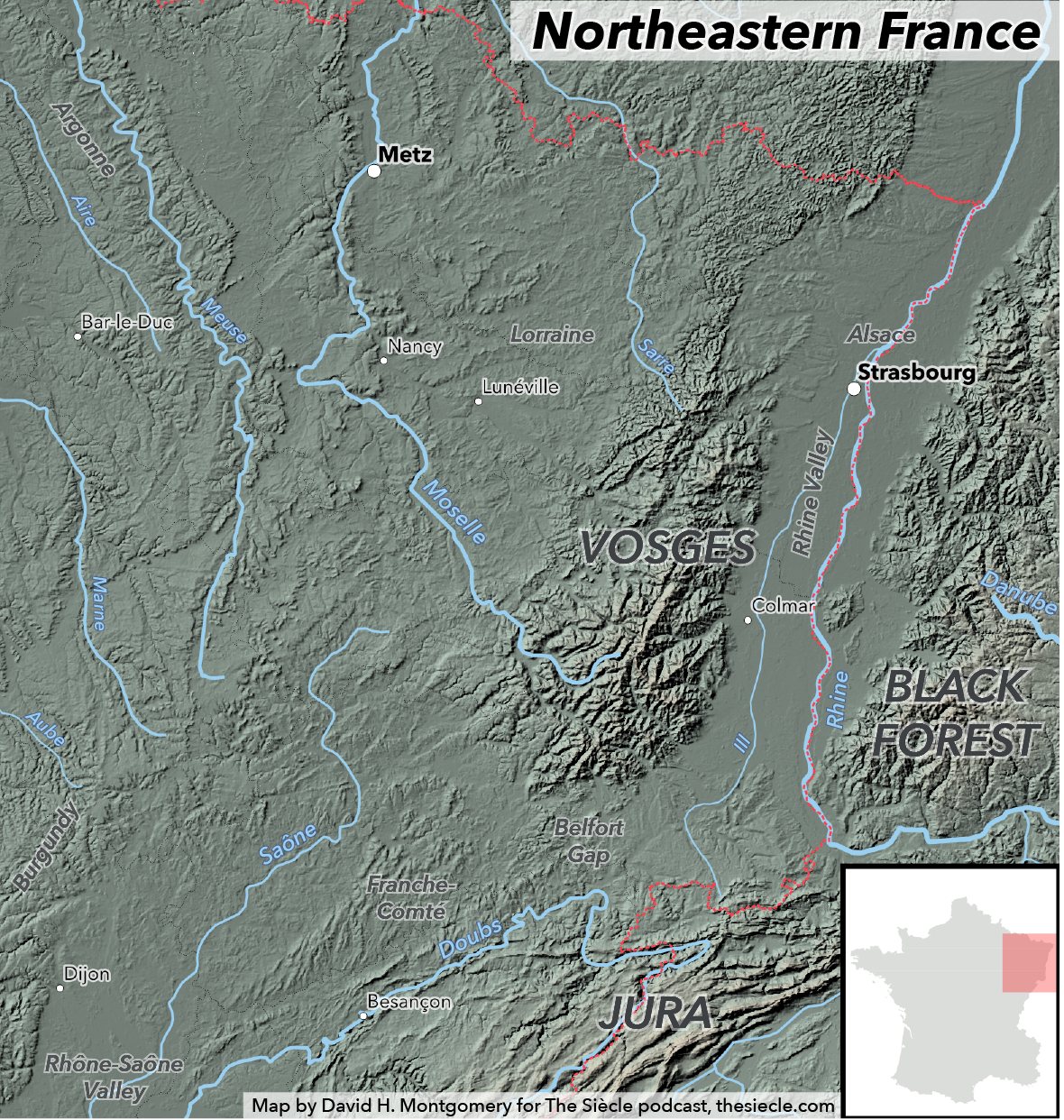

Though the Carbonari recruited around the country, the movement’s primary focus seems to have been Alsace. This region in northeastern France is consistently noted as being extremely Bonapartist throughout this entire period. It was also, as I mentioned in Episode 3, beginning to industrialize. The region had a host of wealthy proto-industrialists, dubbed fabricants, whose status as major employers gave them extensive client networks throughout the region — a so-called “fabricantocracy.”33 The northeast was the only part of the country to elect a majority of left-wing deputies in the 1820 election, otherwise swept by Ultraroyalists.

As a result, Alsace had two key advantages as a springboard for revolution: a friendly populace, and available leadership. To reinforce this, Carbonari in Paris planned to dispatch both rank-and-file activists and senior leaders to Alsace to support their planned uprising. The most notable among these was that aging revolutionary stalwart, the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette was currently a left-wing deputy who cheerfully lent his support to any revolutionary movement that would have him, in whatever fashion he was needed.34 In 1821, Lafayette’s assigned role was to arrive on site, lend his fame and prestige to the rebellion, and help lead a provisional revolutionary government. The Carbonari felt that support from local politicians and businessmen wasn’t enough; they needed a famous general. Ideally, this would be a Napoleonic general, but since no suitable candidates could be found, General Lafayette would suffice to lead the troops.35

Specifically, the troops in question were the garrison at Belfort, a strategic city guarding the road between Alsace and the rest of France.

Notice the “Belfort Gap,” bottom-center.

As a garrison city, Belfort had a military regiment stationed there — the nucleus of the planned Carbonari uprising. Promisingly, in the fall of 1821, Belfort’s old garrison unit, the “impeccably royalist” 55th Regiment, was cycled out and replaced with a new unit, the 29th. The new regiment’s politics weren’t quite certain, but local liberals saw it as an improvement — as demonstrated by the awkward scenario of dueling balls hosted by Belfort elites, with royalists honoring the departing regiment and liberals its replacement.36

Soon enough, though, a number of junior officers in the 29th regiment had joined the Carbonari and begun to bring common soldiers into the conspiracy. Meanwhile agitators from Paris had begun organizing in nearby cities, so that an uprising at Belfort could be transformed from a simple mutiny into a region-wide insurrection.37

The plans were finalized for an uprising on Dec. 29, 1821. The signal was to be the arrival in town of Lafayette. But though the organizers felt they had arranged everything for an “easy and orderly victory,”38 events wouldn’t turn out quite the way the Carbonari hoped.

Unraveling

The first problems came to light on Dec. 18, 1821, and had nothing to do with Belfort. Rather, it was the exposure of a different Carbonari cell, at the cavalry school at Saumur in western France. There are dramatic stories about a fire that night at the Saumur base that killed several soldiers, including a conspirator whose body contained incriminating documents. But in his history of these conspiracies, historian Alan Spitzer found no evidence to back this story up. The fire did happen, but Spitzer concludes the most likely reason the cell there was exposed was a simple one: someone talked. Someone always talks.39

Whoever it was who spilled the beans, the commandant of the cavalry school began investigations. Soon enough two pupils reported that their peers were openly plotting insurrection, which would involve the cadets as well as support from local bourgeois. Arrests were ordered on December 24, sweeping up some of the conspirators, though the lead agitator, a certain Lieutenant Delon, slipped away. The subordinates who weren’t so lucky promptly began talking to their captors — but had little useful to say, having been kept in the dark or actively misled as to most of the actual details. Further confounding efforts of authorities to roll up the cell at Saumur were bureaucratic turf wars between the civil and military officials there, who failed to cooperate and would soon enough be engaged in a furious blame war.40

One of the major Carbonari cells had been disrupted, but none of the authorities immediately realized that the plot spread beyond the Saumur region. So Carbonari agents in Belfort moved ahead with their plans. Lafayette left Paris for his home of La Grange, from which he was ready to travel to Belfort and launch the uprising. But leaders on the ground got nervous and decided to postpone the Dec. 29 uprising while they gathered more information. A new date was set: Jan. 1, 1822.41

But the delay also gave officials in Belfort time to gather more information — and they didn’t have to try very hard. A collection of Parisian Carbonari activists had poured into Belfort for the uprising and apparently thought little of secrecy, enthusiastically breaking into “La Marseillaise” — which, as I covered in Supplemental 8, was banned in Restoration France. Meanwhile several soldiers in the 29th regiment went to their superiors to report a plot to seize the town and raise the tricolor flag. It was the last minute, the evening of Jan. 1 — the night of the uprising.

The regiment’s colonel immediately went to the barracks, where the reports were confirmed by the sight of an entire company turning out with weapons in hand — but unable to give a good answer as to why. The colonel was able to restore authority over the mutinous soldiers, while other officials took control of the town gate and arrested some suspicious people who were loitering nearby.42

With the plot collapsing, the remaining conspirators fled and tried to salvage what they could. Two young men rushed down the highway and managed to intercept Lafayette’s carriage, which was rushing toward Belfort unaware of what had just occurred. Lafayette hastily turned off to a nearby town where he made up an excuse of visiting a friend; other Carbonari burned Lafayette’s revolutionary uniform, which had been sent on ahead to be ready for the uprising.43

Now the seriousness of the matter dawned on the Bourbon authorities. Fifteen soldiers from the 29th were arrested — mostly noncommissioned officers — along with dozens of civilians, including local notables, half-pay officers, and Parisian students. One local attorney’s house was found to contain two tricolor flags, 414 tricolor cockades, and 13 packets of ammunition. A week later, officials in Toulon in southern France uncovered another cell, through incriminating documents and confessions from an informer. Investigators became aggressive, searching the home of a liberal deputy despite his official immunity from prosecution, and even launching an unauthorized cross-border raid into the Grand Duchy of Baden to arrest a Carbonari suspect.44

Despite these crackdowns, the threat began to seem omnipresent across France. On February 5, a general in the western city of Nantes ordered the arrest of several subversive soldiers and officers, who he discovered were part of a secret society with oaths, secret handshakes and ceremonies. As the magnitude of the Carbonari threat became clearer, the whole city was placed on lockdown, with unfortunate consequences; the mayor of Nantes wondered “whether it had been wise to insist on a password from civilians on the streets… since soldiers had already fired on a lady with a baby and a deaf citizen who had failed to respond.”45

The insurrection of General Berton

Below: General Jean-Baptiste Berton. Artist unknown, 1876. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

But the most significant uprising of the entire Carbonari movement in France — the only real uprising to actually go off, in fact — happened back near the town of Saumur where the plot had first been uncovered. The initial investigations there had highlighted the involvement of a half-pay Napoleonic general named Jean-Baptiste Berton, who had gone to ground and evaded capture. But two months later, on Feb. 24, he suddenly surfaced again in the town of Thouars — 22 miles or 36 kilometers southwest of Saumur. Local elements of the National Guard had joined the Carbonari and raised the standard of rebellion with General Berton at their head. Berton rang the village bells to turn out the crowd, marshaled a troop of soldiers and volunteers, and set off on the road to Saumur.

Berton’s manifesto issued that day survives. It is addressed to “the French Army,” and opens by declaring that “All France has risen to recapture its independence” and that “Already our veteran warriors stream in from every quarter to join your fathers, your brothers, and your friends” — something of an overstatement. Berton warns against “the false promises of your chiefs,” highlights the humiliation suffered by half-pay officers, and wraps up by offering a choice: to join the rebellion and fight for national virtue, or to oppose the rebellion and commit treason against the county.46

The purposes of the rebellion were kept rather vague. One famous story goes that when one of Berton’s rebel troops asked him if the battle cry should be “Long live Napoleon II,” the general replied, “Shout whatever you like!”47

Berton’s own proclamation did not salute the health of a Bonapartist heir. He concluded by declaring, “Vive la France! Vive la liberté!,” and signed it, “the general commanding the National Army of the West, Berton.”

This National Army of the West at the time consisted of some 45 soldiers, 30 infantry and 15 cavalry, as well as various hangers-on, though they claimed to people they met that thousands of additional soldiers were pouring in from all directions. Unfortunately for the Carbonari, Berton’s insurrection did not have thousands of reinforcements, and was not executed with clockwork precision: there were delays; the garrison at Saumur was alerted and mobilized; the rebel and regime forces had a long standoff. Eventually, Berton and his men gave up and melted into the woods.48 It was the last gasp of the Carbonari.

Crackdown

While many of the Carbonari continued to form new plots at this point, the initiative had shifted entirely to the authorities. They set out to make an example of the insurrectionaries, with mixed success.

The first step was to ensure order. Hundreds of fresh soldiers were swarmed into trouble spots like the area around Saumur to hunt for fleeing conspirators. The Minister of War told commanders to be ruthless: “one does not parley with a band armed to overthrow the authority of the King.”

But this only got so far, as conspirators fled or hid, often with the support of friendly locals. So the most productive technique involved interrogating one suspect until he spilled the beans about compatriots. A typical example comes from the aftermath of Berton’s uprising, when authorities questioned a Saumur resident named Edouard Beaufils. He revealed that he had plotted with two brothers named Gauchais, a doctor named Caffé, and another man called Coudray. This let them capture the Gauchais brothers and Dr. Caffé, though Coudray slipped the net; as was common, the dragnet nabbed some but not all of the suspects.49

Frustratingly, the Carbonari who remained at large included most of the leaders. Low-ranking conspirators languished in jail while the ringleaders were free. And so, feeling the security of the realm at stake, Bourbon officials set aside any scruples they might have had to get the job done.

We’ve already seen how the Bourbon authorities launched an illegal cross-border raid to capture one Carbaronari conspirator. That wasn’t the last time officials would use effective but dubiously honorable tactics to round up loose ends. Indeed, not one but two different conspirators were arrested via trickery, including the unfortunate General Berton.

As rumors circled about where the fugitive general might be making mischief, the ministry closed down the problematic cavalry school at Saumur and replaced it with squadron of more royalist sentiments. A certain Sergeant Wolfel from the new unit went undercover, making contact with local Carbonari activists and passing himself off as a recruit. They eventually welcomed him in, and — not smart enough to sense which way the wind was blowing — asked him to gather recruits for another coup attempt. As part of this plot, a rendezvous was arranged between Wolfel and the commander of the planned uprising — none other than Berton. The meeting was turned into a trap, which finally snatched up the elusive Berton on June 17, 1822.50 An even more dramatic sting unfolded a few weeks later in Alsace, when the undercover agents mustered up an entire column of ostensible recruits for their target, a half-pay colonel who wanted to spring the Belfort conspirators out of jail, and let him lead them down the road crying “Vive l’Empéreur” before arresting him. Even in the 1820s, critics raised the cry of entrapment.51

Political justice

Still more prominent a target than Berton for the authorities were the men believed to be at the heart of the entire Carbonari conspiracy: political leaders like Lafayette. Right-wing newspapers led the charge to connect the liberal politicians with the uprisings, with the Drapeau blanc saying that after the coup attempts, it was easier to understand “the incendiary speeches of certain deputies”; another paper printed a fake notice, ostensibly from Berton, that implicated Lafayette.52 Of course, as we know, Lafayette was involved in the plots, if not always in the exact way that his opponents believed he was. So were several other prominent liberal deputies.

But as authoritarian as the Bourbon Restoration could be at times, it was still a constitutional monarchy. And Article 52 of the Charter of 1814 declared that “No member of the chamber, during the course of the session, can be prosecuted or arrested upon a criminal charge, unless he should be taken in the act, except after the chamber has permitted his prosecution.” The Chamber was controlled by an ultraroyalist majority, but the authorities wanted to have all their ducks in a row before trying to surmount the political and legal hurdles involved in bringing criminal charges against sitting deputies like Lafayette.

So as Carbonari conspirators were investigated, they were frequently interrogated about any dealings they might have had with deputies. Some told their interrogators what they wanted to hear, like the Carbonari activist who had unwittingly betrayed General Berton to Sergeant Wolfel. He admitted having gone to Paris to plot with Lafayette.53

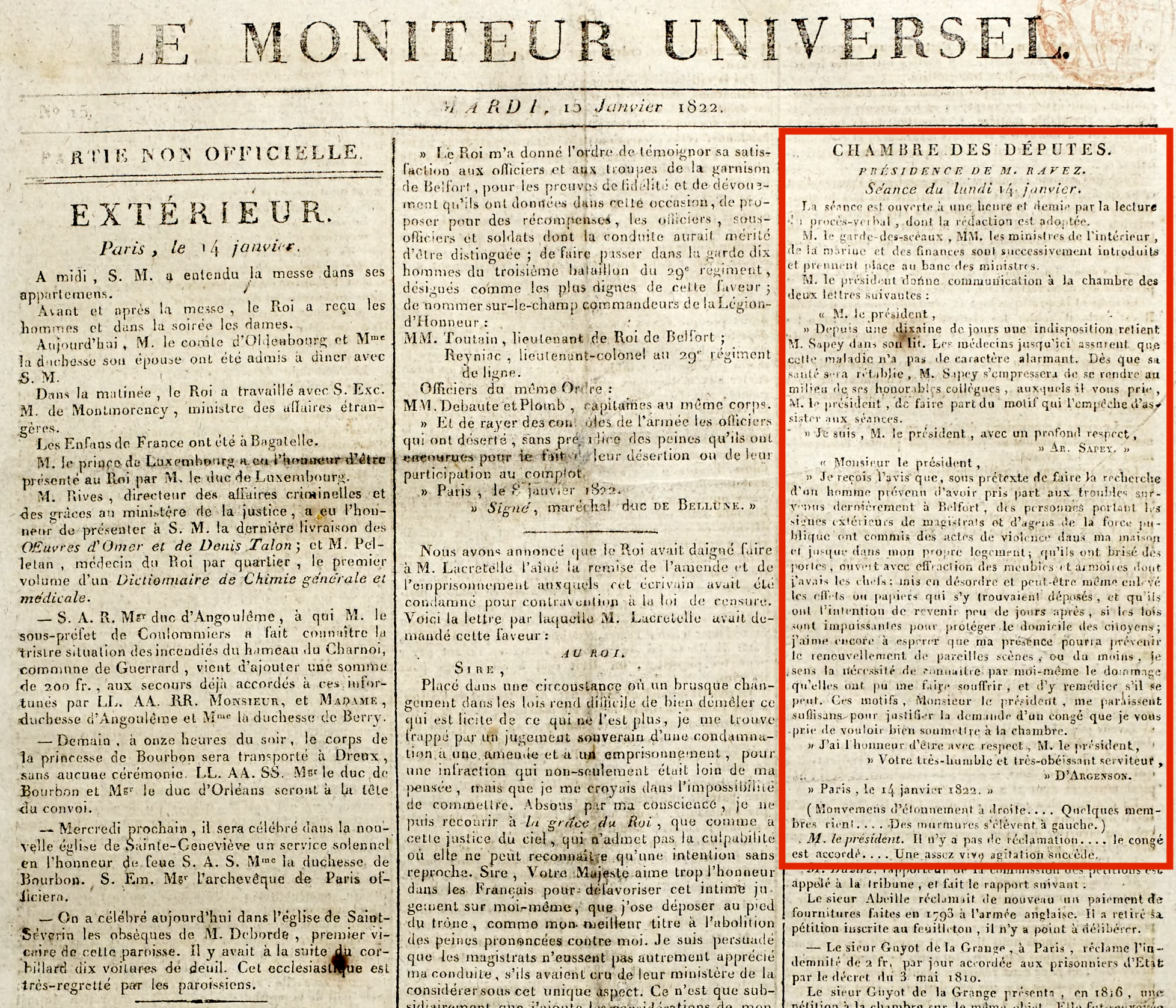

While all this was going on, a range of liberal deputies vigorously defended themselves from the accusations, whether they were true or not. As early as Jan. 14, the Alsatian deputy Marc-René de Voyer d’Argenson rose in the Chamber to protest the search of his house in the aftermath of the Belfort conspiracy. Voyer d’Argenson had absolutely been involved in the Belfort plot, but the search turned up nothing.54 Months later, other liberal deputies such as Benjamin Constant and Jacques Lafitte publicly denied the accusations that they had conspired; both of them were probably even telling the truth.55

Le Moniteur Universel from Jan. 15, 1822, including an article (highlighted) on the deputy Voyer d’Agenson requesting a leave of absence to address authorities searching his house as part of an investigation into a Carbonari plot. Accessed via DigiNole.

But Lafayette did not bother. When prosecutors publicly accused Lafayette of joining the plots, a prominent centrist deputy named Royer-Collard wanted to come to his defense. But before doing so, he checked in with Lafitte to ask “if he was certain that Lafayette was not conspiring.” In the words of historian Sylvia Neely,

Lafitte responded that [Lafayette] most probably was and that he wanted to be accused of it. Royer-Collard asked, “Is he crazy?” On the contrary, Lafitte replied… “Insurrection according to him is the most sacred of duties.”

But what does he want? Royer-Collard insisted. “I’m not sure,” [Lafitte said.] “Lafayette is a monument wandering around in search of its pedestal. If on the way he should find the scaffold or the chair of the president of the Republic, he would not give two cents for the choice between them.”

Later, when Lafitte described this conversation to Lafayette, “the general laughed loudly and agreed that it was true.”56

Below: Artist unknown, picture of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette, late in life. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In August of 1822, it seemed very possible that Lafayette would get his chance at martyrdom. The prosecutor in the trial of Berton specifically mentioned Lafayette in his indictment, saying of a prosecution witness, “that the Marquis de Lafayette paid for his trip; that he received instructions from these gentlemen for the new operation against Saumur.” In response, Lafayette didn’t deny the charges, saying, “I have constantly merited being the object of ill will of the adversaries of [liberty]… I do not at all complain, then, though I have the right to find a trifle cavalier the word ‘proven,’ which [the prosecutor] used in regards to me.”57

In August of 1822, it seemed very possible that Lafayette would get his chance at martyrdom. The prosecutor in the trial of Berton specifically mentioned Lafayette in his indictment, saying of a prosecution witness, “that the Marquis de Lafayette paid for his trip; that he received instructions from these gentlemen for the new operation against Saumur.” In response, Lafayette didn’t deny the charges, saying, “I have constantly merited being the object of ill will of the adversaries of [liberty]… I do not at all complain, then, though I have the right to find a trifle cavalier the word ‘proven,’ which [the prosecutor] used in regards to me.”57

Despite his apparent unconcern, proving Lafayette’s involvement wouldn’t be so easy. Their star witness, the Carbonari agent who had confessed to meeting Lafayette, suddenly updated his story to describe the “Lafayette” he had supposedly met: a man in his fifties, short at about 5’2” or 1.57 meters tall, with long sideburns. Since Lafayette was in his sixties, of medium height, and clean-shaven, this severely undermined the testimony — the only concrete link investigators had dug up between the actual conspirators and their alleged superiors in Paris. The witness stuck to this description despite being berated in open court by the presiding judge.58

Nailing people like Lafayette or Voyer d’Argenson seemed especially hard given that lots of people who’d actually been caught in the act seemed to be dodging punishment. The great trial of the Belfort conspirators — 23 of whom were in custody — ended in acquittals on conspiracy charges for all involved, though four were convicted of a lesser charge. This was despite the fact that the prefect had assembled a jury of men known for “their monarchical principles” to try to secure a conviction.59

Now, this isn’t to say that everyone skated. Too many people had been caught in the literal act of rebellion for even friendly juries to acquit. Such a fate awaited General Berton, who went on trial along with 39 other defendants. Berton refused to accept his court-appointed attorney, and gave a scattershot defense of himself, in which he claimed to have only led a peaceful demonstration in support of the 1814 Charter. Unsurprisingly, this wasn’t terribly persuasive, and Berton was sentenced to death, along with five other co-defendants. Two had their sentences commuted by the king, but Berton and two others went to the guillotine. Most of the other defendants were given prison sentences of one to five years; only two of the 40 in this trial were acquitted.60

The Four Sergeants of La Rochelle

A dramatic illustration from an 1890 book about the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle, in which the leader of the titular sergeants, Sgt. Jean-François Bories, lifts his hand to swear an oath of loyalty to the Carbonari. The book and image are both part of the liberal hagiographic tradition of the Four Sergeants. Artist unknown. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

But the most famous Carbonarists to die as a result of the botched uprisings were four young noncommissioned officers from the 45th Regiment, which had been dispatched in early 1822 from Paris to the southwestern port city of La Rochelle. Unlike Berton, the so-called Four Sergeants of La Rochelle never launched an uprising. But they were plotting one, and ended up on trial for their lives after being fingered by informants. Now, some of these informants would later recant their confessions, claiming they had been given under what my history book describes as “intolerable pressure”;61 I genuinely don’t know if that’s meant to be a euphemism for physical torture or not. But recanting didn’t save them.

The trial of these four relative nobodies took on an outsized importance, in part because unlike the other trials, the Sergeants of La Rochelle were on trial in Paris itself, not out in the provinces, which let it get far more attention from the press and international observers.

Below: Louis Antoine François de Marchangy, artist unknown, before 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The prominence of the four sergeants’ trial was further elevated by the lead prosecutor, a man named Marchangy, who in addition to being a lawyer was an acclaimed author. Marchangy’s big speech at the trial lasted five hours, and was published as a 196-page book. The speech transcended legal matters for the metaphysical, speaking of how the entire world had been corrupted by “perfidious machinations” and “deleterious principles,” of “programs of sedition from the Apennines to the Bosporus, and from Lisbon to the banks of the Orinoco.” The “rhetorical tour de force” made him a star in right-wing political circles, and he apparently received the personal thanks of more than one European monarch for his efforts against revolution.62

The prominence of the four sergeants’ trial was further elevated by the lead prosecutor, a man named Marchangy, who in addition to being a lawyer was an acclaimed author. Marchangy’s big speech at the trial lasted five hours, and was published as a 196-page book. The speech transcended legal matters for the metaphysical, speaking of how the entire world had been corrupted by “perfidious machinations” and “deleterious principles,” of “programs of sedition from the Apennines to the Bosporus, and from Lisbon to the banks of the Orinoco.” The “rhetorical tour de force” made him a star in right-wing political circles, and he apparently received the personal thanks of more than one European monarch for his efforts against revolution.62

Comité directeur

Because as real as the Carbonari conspiracies were, Europe’s guardians of order believed they were facing a far larger and more menacing conspiracy. The name inevitably given to this secret plot was the “comité directeur,” or steering committee, which was talked about in the same way comic book characters today might discuss a league of supervillains like Hydra — it was headquartered in Paris, of course, but had agents everywhere, including all the most infamous rogues, and plotted the downfall of everything that was good and true in the world with devious subtlety.

Below: George Dawe, “Portrait of Emperor Alexander I,” 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Tsar Alexander of Russia, for example, became convinced that the comité directeur had caused a recent revolution in Greece — not for the sake of the Greeks, but to distract the Tsar from crushing the rebellion in Naples. “Be no doubt,” Alexander wrote, “that the impulse for this insurrectionary movement was given by that same comité central directeur of Paris, in the hope of making a diversion… and preventing us from destroying one of those synagogues of Satan, established solely in order to defend and propagate his anti-Christian doctrine.” By all these theologically laden and anti-Semitic terms, just to be clear, Alexander meant liberalism.

Tsar Alexander of Russia, for example, became convinced that the comité directeur had caused a recent revolution in Greece — not for the sake of the Greeks, but to distract the Tsar from crushing the rebellion in Naples. “Be no doubt,” Alexander wrote, “that the impulse for this insurrectionary movement was given by that same comité central directeur of Paris, in the hope of making a diversion… and preventing us from destroying one of those synagogues of Satan, established solely in order to defend and propagate his anti-Christian doctrine.” By all these theologically laden and anti-Semitic terms, just to be clear, Alexander meant liberalism.

The British foreign minister, Viscount Castlereagh, agreed, speaking of “that organized spirit of insurrection which is systematically propagating itself throughout Europe.” In Austria, Metternich wrote that “it has been proved that the seditious elements of all countries and of all hues have established a center of information and action.” One of the few skeptics of this line of thought was the French prime minister, the Duc de Richelieu, who scornfully wrote that “it is perhaps more convenient to attribute to an invisible power whose lever is in France… catastrophes whose real cause could more simply be found in the weakness and incompetence of those governments which a mere breath has been enough to overthrow.”63

Richelieu was right: though liberals and would-be revolutionaries did keep in touch, there was no central organizing committee behind the spree of revolutions that popped up around Europe in the early 1820s. The comité directeur, as he keenly saw, was a convenient myth. But as I covered in Episode 18, Richelieu was now gone, forced out in December 1821, immediately before the Carbonari plots came to light. The new regime in France was more open to the prospect of a nefarious committee behind all the revolutions in Europe — especially after the Carbonari made it clear that there was definitely some real conspiring going on.

So the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle, minor members of a minor branch of a conspiracy that had already failed, found the crushing weight of this massive metaphysical construct bearing down on them. Their only hope was to confess and identify higher-ranking Carbonarists. But the sergeants refused, even the ones who had previously confessed before recanting.

Some people saw in this a shameful move by the Carbonari leaders, letting their naive followers take the blame so they could stay safe; one historian attributes this to pressure from their attorneys, who were, of course, also Carbonari.64 But however they chose it, by the end, the four sergeants decided to embrace their role as martyrs for the liberal cause. After being convicted and sentenced to death, the four asked to be executed together, and went to the guillotine crying out “Long live liberty!”65

They were four of 11 men to be executed in 1822 for their role in Carbonari conspiracies in France, along with Berton and several others. Dozens more were imprisoned, fined, or fled into hiding or exile to avoid punishment — including several death sentences passed down in abstentia.66

The Four Sergeants of La Rochelle hear their death sentences on Sept. 20, 1822. Artist unknown, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Aftermath

But other people tried at the same time as the Four Sergeants were acquitted, including those who had been much more centrally involved in the conspiracies. That was the story across most of the Carbonari trials: frequent acquittals that became something of an embarrassment for the government,67 especially because of the failure to convict any of the central leaders on the infamous comité directeur.

But as it turned out, the convictions the government did secure were enough. As Neely argues, “by preserving strict legal procedures in its prosecution of the accused, the government allowed some of the guilty to escape but ultimately proved even to skeptics that those condemned were genuine conspirators.”68

So even though only a handful of Carbonari were punished for their conspiracies, the movement was completely crushed, and the Bourbon regime had its domestic political position greatly improved. Unlike the Bourbon kings of Spain and Naples, Louis XVIII’s government had not collapsed at the slightest push, but had proven itself durable — a safer bet for opportunistic politicians to support than it might have appeared beforehand. There were no more uprisings or serious conspiracies in the years that followed. That included in 1823, when the French army invaded Spain to crush the revolutionary government there. Liberals had hoped that such an invasion would prompt a backlash from the army, while conservatives had feared exactly this. But as I discussed in Episode 18, the French army stayed loyal. Any remaining revolutionary elements in it had been purged, or chastened into obedience. As the liberal journalist Adolphe Thiers observed in the winter of 1822, in the aftermath of the failed Carbonari uprisings, French soldiers were “silent” about political matters, partly by inclination, and partly “because they may be overheard.”69

Years later, surviving leaders in the Carbonari looked back on the conspiracies with a degree of bemusement. With the benefit of hindsight, the confidence of 1821 seemed more like folly. As the Carbonarist Armand Carrel later reflected, “Why did we have the mad idea that a government supported by laws and by the weight of inertia of 30 million men could be overturned by the plots of law students and second lieutenants?”70

Considered from a distance, the Carbonari can have an air of the tragicomic. Fueled by a powerful sense of the righteousness of their cause, the Carbonari built an impressive nationwide conspiratorial network almost overnight — but then saw everything collapse in a few months of bungling. Every local plot ended up with one of three fates: it was betrayed to the authorities, it launched an insurrection that swiftly collapsed, or the conspirators lost their nerve and did nothing. The plots that did get off the ground were scattershot, not synchronized. This verdict was clear very soon after the actual events, as Carrel’s scornful self-judgment reflects.

We shouldn’t be too hard on the Carbonari, though. For one, the magnitude of their nationwide network is truly impressive. They were sloppy, yes, but the classic conspiratorial cell structure successfully contained the damage when one cell was caught — members didn’t know many other conspirators they could blame. And the core of the conspiracy, the radical activists in Paris, were never penetrated by police. The Carbonari were betrayed when they tried to recruit into new social circles, especially their aggressive and recklessly open solicitation of active-duty soldiers.71

Another ex-Carbonarist, Paul Dubois, lamented that in future histories, “the two or three pages devoted to these forgotten ‘fanatics’ will portray neither their spirit, their virtues, their passions, their illusions, nor their faults. Only we who, as contemporaries, dreamed the same dreams, ran the same risks, showed the same devotion, could recapture and portray them. Yet we would have to be young again, and already we are old.”72

Dubois wasn’t that wrong. For one thing, our documentary evidence on the Carbonari is limited, since as an illegal secret society many details were never recorded to paper, or were burned by those who did. The accounts we do have were often written decades after the fact.73

Now, the Carbonari conspiracies weren’t forgotten, with the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle in particular becoming famous liberal martyrs for decades to come.74 But much of the discussion of these uprisings that happened has been focused on score-settling, as the survivors tried to find scapegoats for the failure of their plots. This happened from the very start: one active Carbonarist named Grandmesnil was fingered as a police agent provocateur in an attempt to weaken the case against some Carbonari defendents. Conveniently, Grandmesnil couldn’t refute this fact because he was in hiding — though in one dramatic scene, he covertly visited the Chamber of Deputies to get help fleeing the country from Carbonarist deputies at the exact moment when other liberal deputies took the podium to say this entire so-called plot was just a provocation by the police agent Grandmesnil. Lafayette’s son, Georges Washington Lafayette, had to physically restrain Grandmesnil from rushing to the podium to defend his honor, and he continued to be defamed as a police agent into the 1840s.75

Now, the Carbonari conspiracies weren’t forgotten, with the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle in particular becoming famous liberal martyrs for decades to come.74 But much of the discussion of these uprisings that happened has been focused on score-settling, as the survivors tried to find scapegoats for the failure of their plots. This happened from the very start: one active Carbonarist named Grandmesnil was fingered as a police agent provocateur in an attempt to weaken the case against some Carbonari defendents. Conveniently, Grandmesnil couldn’t refute this fact because he was in hiding — though in one dramatic scene, he covertly visited the Chamber of Deputies to get help fleeing the country from Carbonarist deputies at the exact moment when other liberal deputies took the podium to say this entire so-called plot was just a provocation by the police agent Grandmesnil. Lafayette’s son, Georges Washington Lafayette, had to physically restrain Grandmesnil from rushing to the podium to defend his honor, and he continued to be defamed as a police agent into the 1840s.75

Above: the illustrated cover to a novel about the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle. The novel, Les Quatres Sergeants de La Rochelle by Clémence Robert, was published in 1849. This particular edition, with cover art by Auguste Belin, dates from 1870. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The most pronounced battle over the Carbonari was between the movement’s young foot soldiers and the senior leaders who some felt had betrayed them to save their skins. Picture Lafayette’s carriage turning aside on the road to Belfort, or the liberal deputies allowing the Four Sergeants to head to the gallows rather than allow themselves to be fingered as the ringleaders. One activist wrote that he had quit the Carbonari in disgust after seeing that “the unfortunate noncommissioned officers of La Rochelle had been abandoned to the executioner.” Some alleged that the cause of the downfall was that the pure revolutionary ranks had been corrupted by letting in Bonapartists and others insufficiently devoted to the cause.76 Even moderate members of the opposition, who hadn’t participated in the plots, recoiled from the disasters, with the opposition politician Casimir Périer allegedly saying of his Carbonari colleagues, “How can we have anything to do with people who, after leading us to the edge of the precipice without our realizing it, skip out and leave us in the lurch?”77

It’s not worth getting too deep into the weeds here, but suffice to say that for every charge of cowardice there was a counter-charge of recklessness. Dubois, who I just quoted extolling the forgotten virtues of the Carbonari, also bragged of his wisdom in preventing the Carbonari of Brittany from launching a “premature uprising.”78

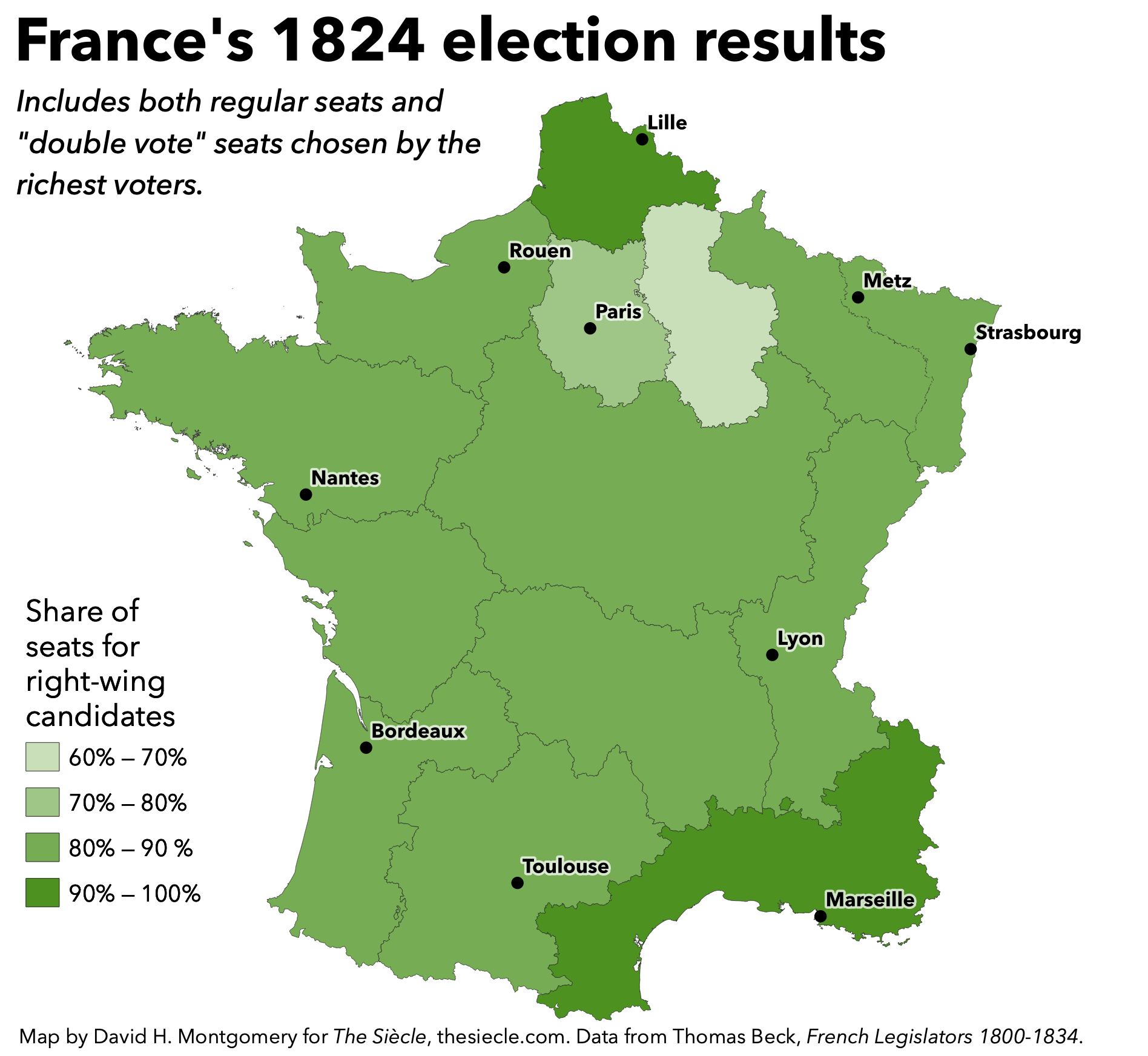

Regardless of the long-term impact of the Carbonari movement, the short term was a disaster. Not only were they crushed, but they sparked a political backlash. The limited, wealthy French electorate recoiled at the very real proof of conspiracies that the regime put forward, along with some of the more fanciful exaggerations. The entire liberal opposition was now tarred with the brush of revolution. This was true for some prominent liberals, and untrue for others, but both currents of liberals suffered, especially among the wealthiest 1 percent of French men who were entitled to vote in the Bourbon Restoration.

In 1824, after defeating the French Carbonari and successfully restoring King Ferdinand to the throne in Spain, King Louis dissolved the Chamber of Deputies and called for new elections. Between the regime’s newfound popularity, its usual election chicanery, and the extra deputies elected by France’s richest electors under 1820’s “Law of the Double Vote,” the result was a landslide: 34 deputies for the Left against 416 for the right and far-right.79

Among the electoral casualties was Lafayette, who was defeated in each of the several different departments where he was a candidate. With the hope of liberal change in France hopeless both through the ballot and the bayonet, a discouraged and nearly bankrupt Lafayette decided to finally accept an invitation arranged by some of his pen-pals, who included Thomas Jefferson and the sitting American president James Monroe. He would leave France and return to the country whose liberty he had championed since 1777: the United States.80

Below: François Gérard, “King Louis XVIII in his office in the Tuileries Palace,” 1823. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Left behind in France was King Louis XVIII. The king had been a personal and political enemy of Lafayette dating all the way back to the 1770s, when a young Lafayette had snubbed the then-prince at a masquerade ball, and the subsequent decades had not endeared either man to the other. Now, the two had been on opposite sides of a great struggle for control of France, one that had been won decisively by Louis. The king who had seen his reign careen from one crisis to another was finally secure on his throne. Louis’s address opening the French Chambers on Jan. 28, 1823, declared: “The domestic situation of the Kingdom has improved: the judicial process, honorably applied by the juries, wisely and courageously directed by the magistrates, has put an end to plots and attempted insurrections which had been encouraged by the dream of invulnerability.”81

Left behind in France was King Louis XVIII. The king had been a personal and political enemy of Lafayette dating all the way back to the 1770s, when a young Lafayette had snubbed the then-prince at a masquerade ball, and the subsequent decades had not endeared either man to the other. Now, the two had been on opposite sides of a great struggle for control of France, one that had been won decisively by Louis. The king who had seen his reign careen from one crisis to another was finally secure on his throne. Louis’s address opening the French Chambers on Jan. 28, 1823, declared: “The domestic situation of the Kingdom has improved: the judicial process, honorably applied by the juries, wisely and courageously directed by the magistrates, has put an end to plots and attempted insurrections which had been encouraged by the dream of invulnerability.”81

Louis had a ministry supported by an overwhelming majority in the Chamber of Deputies; he had co-opted the ultra-royalists on the right and neutralized the liberals on the left. Those liberals who remained in positions of influence after the suppression of the Carbonari and the landslide election of 1824 were, historian Philip Mansel argues, “so monarchical that they accepted the Bourbons almost… completely.” Even the masses, denied a formal role in the political process, were quiet. One moderate politician toured the country and concluded that “the people had abdicated,” with Louis governing with less popular opposition than any of his ancien régime forebears had.82 And now the most prominent living symbol of opposition to the Bourbon Restoration had left the country.

This episode has already gone on very long, so I’ll wrap things up quickly. If you’re having trouble keeping all this straight, trust me: I’m with you. There’s a reason this episode took me so long to write. But this is an episode where it might be especially useful to visit the online version of the episode at thesiecle.com/episode23. In addition to a full script and footnotes, you’ll also be able to see pictures of people like General Berton and the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle, check out a map I made to pinpoint the locations of cities like Thouars and Belfort, and read the annotated timeline I made of all the confusing events in the Carbonari conspiracies. That’s t-h-e-s-i-e-c-l-e dot com, slash episode23.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Carbonari movement, I’ll recommend a few books, links to which you can also find at thesiecle.com/episode23. Alan Spitzer’s Old Hatreds and Young Hopes: The French Carbonari Against the Bourbon Restoration is an entire book about these uprisings, and this episode wouldn’t exist without it. Sylvia Neely’s Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 1814-1824 has provided crucial insight into one of the most important Carbonari conspirators, while Adam Zamoyski’s Phantom Terror: Political Paranoia and the Creation of the Modern State, 1789-1848 was helpful in providing a broader European perspective.

Thank you to all of you for bearing with me during this over-long hiatus as I wrangled this monster of an episode into shape. I hope to release future episodes much more regularly, starting with Episode 24, which follows the Marquis de Lafayette out of France for his seminal return visit to the United States, in conversation with Lafayette expert Alan Hoffman. Join me next time for Episode 24: Lafayette in America.

Timeline of the Carbonari conspiracies, uprisings and trials

- July 1821: French authorities at the cavalry school in Saumur receive initial reports about a seditious cell organized at the school, but treat the reports skeptically.83

- Dec. 14, 1821: An ultra-royalist government led by Joseph de Villèle takes power after the resignation of the prior prime minister, the Duc de Richelieu.

- Dec. 23, 1821: Given firmer information from informants about sedition in the ranks, the commandant of the Saumur cavalry school orders arrests, which take place the next day. Under interrogation, the arrestees name names, but the full scope of the conspiracy remains unclear.84

- Dec. 29, 1821: The original date intended for a Carbonari uprising in the garrison town of Belfort, before leaders postpone it at the last minute.85

- Jan. 1, 1822: On the new date set for the Belfort uprising, the plan is betrayed to authorities at the last minute. Garrison commanders launch patrols of the town and nip the planned uprising in the bud. On his way to Belfort to lead the uprising, the Marquis de Lafayette is warned of its failure and turns away. Over the next two weeks, a broad investigation arrests 15 soldiers, a local gendarme, and 33 civilians.86

- Jan. 14, 1822: The liberal deputy Marc-René de Voyer de Paulmy d’Argenson (usually referred to as “Voyer d’Argenson”) rises before the Chamber of Deputies to defend himself against charges of being involved in the Belfort conspiracies, and is granted a leave of absence.87

- Jan. 16, 1822: Authorities in the southern naval city of Toulon arrest suspects after being tipped off to a Carbonari conspiracy there; an informer tells officials that plotters are part of an organization called the “Carbonari.”88

- Jan. 28, 1822: Several soldiers of the 45th Regiment on its way from Paris to La Rochelle are arrested after brawling with a rival, royalist regiment. Later investigation would uncover Carbonari membership among some of the officers, who would later go on trial as the “Four Sergeants of La Rochelle.”89

- Feb. 5, 1822: A number of soldiers are arrested under suspicion of sedition in the western port city of Nantes; under questioning they admit to being part of an organization called “Carbonari” or “Charbonnier,” with ties to a national network controlled from Paris.90

- Feb. 21, 1822: The Saumur trials begin, with eight cavalry students and three noncomissioned officers facing charges. Five days later, nine of the 11 are convicted, with three sentenced to death (one in absentia).91

- Feb. 24, 1822: Ex-general Jean-Baptiste Berton wakes the residents of Thouars in western France, near Saumur, by ringing the bells and flying the revolutionary tricolor flag. With townspeople and a dissident group of National Guards, Berton marches on Saumur, but after a standoff on the bridge into Saumur he abandons his attempt and disperses his force into the countryside by dawn the next day, without fighting.92

- April 2, 1822: Three junior officers in a Strasbourg artillery regiment are arrested as Carbonarist conspirators. 93

- April 29, 1822: A sergeant from Saumur is executed for his role in the conspiracies (the other non-absentia Saumur soldier sentenced to death having received a lower sentence on appeal).94

- May 4, 1822: A court in Toulon convicts two Carbonari conspirators, sentencing one to death; the sentence is carried out on June 10.95

- June 17, 1822: Betrayed by a police agent under cover as a Carbonari, General Berton is arrested at a farm near Saumur.96

- July 2, 1822:

Ex-Col. Augustin Caron (right97) sets out with a squad of soldiers to try to rescue the Belfort prisoners, but the soldiers are plants and Caron is arrested after being allowed to compromise himself.98

Ex-Col. Augustin Caron (right97) sets out with a squad of soldiers to try to rescue the Belfort prisoners, but the soldiers are plants and Caron is arrested after being allowed to compromise himself.98 - July 22, 1822: A trial in Alsace of 23 accused of the Belfort conspiracy (plus another 21 still at large) begins, but after a few weeks the jury acquits 19 and convicts four of a lesser charge.99

- July 22, 1822: On the same day that the Alsace trial begins, a secondary trial of the Strasbourg conspirators begins. All three defendants are given only minor sentences: fines, and for one, three months in prison.100

- Sept. 11, 1822: A jury convicts Berton and sentences him and five other conspirators to death.101

- Sept. 21, 1822: The “Four Sergeants of La Rochelle” are guillotined, one day after being convicted and sentenced to death, following the failure of a scheme to rescue them from prison.102

- Oct. 1, 1822: After being convicted by a military tribunal, Col. Augustin Caron is executed by firing squad.103

- Oct. 5, 1822: Berton is guillotined after his appeals and request for royal clemency were both denied.104

- November 1822: Liberal journalist Adolphe Thiers arrives in the Pyrenées to report on the civil conflict in Spain, and the mood of the French soldiers stationed there in advance of a possible military intervention.

- April 7, 1823: France invades Spain to suppress a liberal revolution and restore King Ferdinand to power. Despite fears that the French army might mutiny, it carries out its mission successfully.

- Feb. 25 and March 6, 1823: The two rounds of the 1824 French legislative elections return a landslide victory for the ultra-royalists; among the liberals defeated is the Marquis de Lafayette.105

- July 13, 1824: Lafayette boards the packet boat Cadmus bound for the United States of America.106

-

Alan Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes: The French Carbonari Against the Bourbon Restoration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), 80. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 86. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 98. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 104. ↩

-

Anthony H. Halt, “The Good Cousins’ Domain of Belonging: Tropes in Southern Italian Secret Society Symbol and Ritual, 1810-1821,” Man 29, no. 4 (Dec. 1994). ↩

-

Adam Zamoyski, Phantom Terror: Political Paranoia and the Creation of the Modern State, 1789-1848 (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 170. Richard J. Evans, The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914 (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), 39-40. ↩

-

Zamoyski, Phantom Terror, 283. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 233-4. ↩

-

The Italian Carbonari called their cells “vendita,” which means “stand of timber,” in keeping with their mythology as charcoal burners. The French transliterated that to “vente,” which means “sale.” Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 233. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 233-4. Some Charbonnerie documents speak of a much more complicated structure, but if authentic, these more elaborate structures appear to have been more aspirational than real. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 236. ↩

-

Zamoyski, Phantom Terror, 283-4. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 230. All these general rules had exceptions in practice. The cell structure, meant to prevent conspirators from knowing too much in case they got caught, could be more suggestion than rule. One of the more famous French conspirators knew Carbonari from three different ventes. Peter Savigear, “Carbonarism and the French Army, 1815-1824,” History 54, no. 181 (June 1969), 200. Some members even claimed not to know they were joining a revolutionary organization, and some of them backed out once they found out. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 244. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 235. ↩

-

R. John Rath, “The Carbonari: Their Origins, Initiation Rites, and Aims,” The American Historical Review, 69 no. 2 (Jan. 1964), 357-9. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 233. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 88. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 320-1. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 89. One such lodge was the “Amis de la Vérité,” or “Friends of the Truth”, founded sometime between 1818 and 1821; under the formal aegis of normal masonry it “became a sort of permanent seminar for the boldest discussions of political and philosophic issues” and a way to bring together “seasoned sympathizers, spirits requiring a certain preparation, and vacillators who could be brought in without being frightened by the idea of a plot.” Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 221-4. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 16, 143. ↩

-

Dubbed the “Paul I treatment,” after the fate of the former Russian emperor. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 152. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 241-3. ↩

-

Robert B. Carlisle, The Proffered Crown: Saint-Simonianism and the Doctrine of Hope (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 21. Louis Henry and Yves Blayo, “La population de la France de 1740 à 1860,” Population 30, no. 1 (1975), 100. ↩

-

“Age pyramid 2020 – France and metropolitan France,” INSEE, 2020. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 238-40. ↩

-

Being sent home with a half-pay pension might not sound like a terrible outcome, but a host of restrictions made it widely resented. The half-pay officers were obligated to return to the community where they had enlisted and remain there. Since they were still nominally in the army, they couldn’t work other trades. They could always quit, but that would cut off hopes of one day being called back up (which some eventually were, but only a few). The half-pay officers, or demi-soldes, were left to waste their days on extremely limited salaries, and it’s no surprise many of them spent it grumbling about their treatment. Adding insult to injury, the government saw them as a political danger and so subjected them to intense police surveillance. Despite all this, only a small share of half-pay officers have been identified as seditious; “many of them were ostentatiously loyal in the hope of recall.” But “a very vocal and highly visible minority” were active in political opposition, especially in Paris. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 22-3. Zamoyski, Phantom Terror, 134-5. ↩

-

Savigear, “Carbonarism and the French Army,,” 202-4. Alfred de Vigny, Servitude et grandeur militaires [Recollections of Military Servitude], in Lights and Shades of Military Life, edited by Charles James Napier, translated by Frederic Shoberl (London: H. Colburn, 1840), 22-26. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 281-3. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 245-7. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 243-4. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 182. Sylvia Neely has a different take, that Bonapartists were already collaborating with republicans before Napoleon’s death. but that his death helped republicans get over their misgivings about whether a revolution might simply lead to another Bonapartist dictatorship. Sylvia Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 1814-1824: Politics and Conspiracy in an Age of Reaction (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 194. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 44-5, 59. ↩

-

The author Stendhal added that while waiting for such heroic events, the 64-year-old Lafayette passed his time “squeezing from behind the petticoats of the pretty young girls, ‘and that often and without too much embarrassment.’” Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 190. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 248. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 60. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 247. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 247. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 79. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 80-3. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 196. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 248. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 249, 85. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 196-7. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 87, 96-8, 90, 94. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 100-2. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 110-1. ↩

-

Sudhir Hazareesingh, The Legend of Napoleon (London: Granta Books, 2004), 115. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 109-14. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 116. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 132-3. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 136-9. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 199. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 118. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 212. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, Jan. 15, 1822. Accessed via Diginole: http://fsu.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu%3A560720#page/Page+1/mode/2up. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 90. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 344n13. Benjamin Constant appears to have had nothing to do with the plots. And while the banker Jacques Lafitte was widely believed to be funding the plots, this was “erroneous.” Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 188. Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 199. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 224. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 214. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 135, 180. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 161-3. The lesser charge, “nonrevelation of conspiracy,” was something of a logical stretch, as sometimes happens when sympathetic juries feel a need to convict on something but don’t want to do so on serious charges. “As the first president of the court commented with disgust, no one had been convicted of a plot or complicity in a plot, but Tellier, who had told all, was convicted for not having revealed it.”. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 182-3. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 171. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 171-2. ↩

-

Zamoyski, Phantom Terror, 274-7. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 184. ↩

-

Technically, three of them cried “Vive la Liberté,” and the fourth called out “French blood is about to flow!” Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 175. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 219. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 163. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 220. ↩

-

Adolphe Thiers, The Pyrenees and the South of France, During the Months of November and December 1822, translator unknown (London: Treuttel and Würtz, Treuttel, Jun. and Richter, 1823), 168. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 222. ↩

-

Alan B. Spitzer, The French Generation of 1820 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 27. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 300-1. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 211. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 217. “The fate of these four young men, who faced death courageously, captured the public imagination as no other victims of the Carbonarist trials would. Many popular books about them have appeared throughout the years, and two cafés in Paris still bear the name ‘Aux Quatres Sergeants de La Rochelle.’” ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 215. Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 258. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 260-3. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 184. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 263. ↩

-

Thomas D. Beck, French Legislators 1800-1834: A Study in Quantitative History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 175. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 253-4. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 189. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 400-1. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 78. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 80. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 196. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 84, 87. Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 196-7. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 90/MONITEUR. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 98. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 119-23. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 101. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 152-4. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 109-113. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 129-30. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 154. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 156. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 132-3. ↩

-

Col. Augustin Caron, artist unknown, c. 1850, public domain via Wikimedia Commons ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 136-7. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 161-3. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 165. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 182. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 174-5. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 186. ↩

-

Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes, 183. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 249-50. ↩

-

Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 263-4. ↩