Episode 27: Mission from God

Bells rang, cannons fired, and crowds cheered the procession set forth from the cathedral of Clermont-Ferrand. It was a feast for the eyes and ears of as many as 50,000 people gathered to watch1 — but also, its organizers hoped, a feast for the soul.

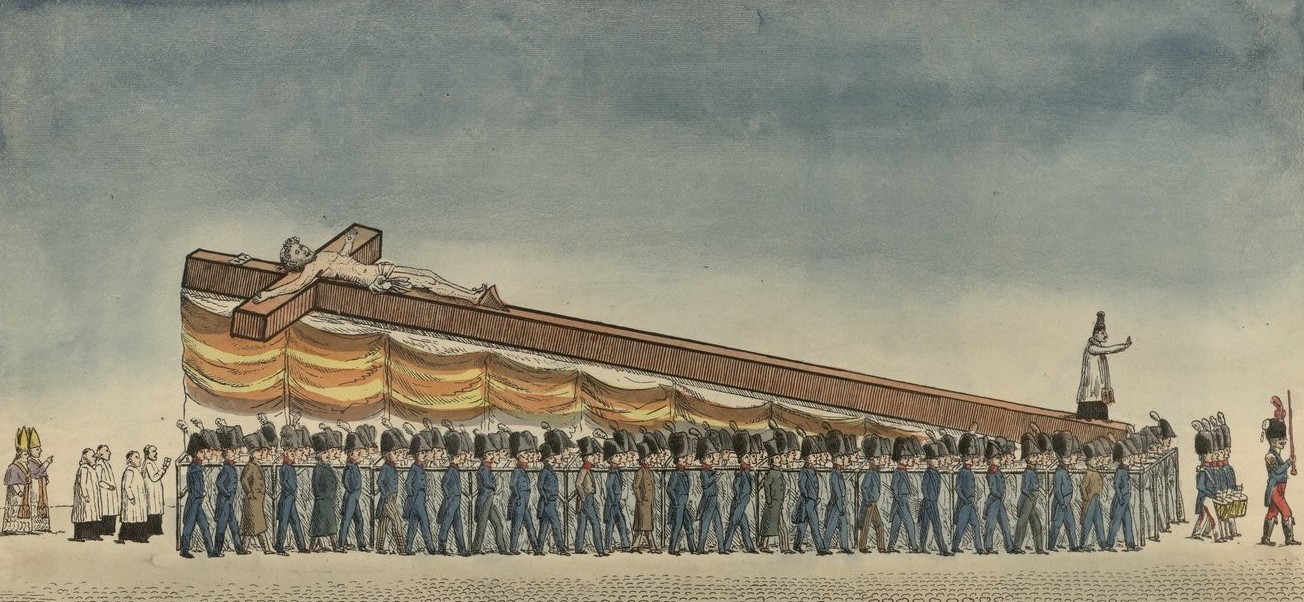

It was April 23, 1818, and parade streaming through Clermont was not in honor of the city, or King Louis XVIII, but in honor of God. Its centerpiece was not a float, but an enormous crucifix — 42 feet long, 10 feet wide, adorned with a nine-foot-tall statue of the crucified Christ, perhaps weighing more than 6,000 pounds in total. The people of Clermont — or many of them, anyway — were here despite a light rain to rededicate their city to God and the Catholic Church.2

The faithful had been coming for weeks, for sermons and hymns, ceremonies and retreats, communion and confession. Local priests had stepped aside for a group of 16 visiting missionaries, here to spread the faith not in pagan lands abroad, but home in France itself. France had long prided herself as the “eldest daughter of the Church,” but had now become a den of sacrilege and atheism. The terrible sins of the Revolution were still festering a generation later. Now the Church was calling its children home.

The centerpiece of this entire endeavor was the ceremony of the mission cross, a gargantuan monument to an entire city’s piety. Marching through the streets of Clermont were more than 3,500 people, including hundreds of clergy, National Guard divisions, large contingents of young women dressed in white and older women dressed in black, and 12 units of 100 men, taking turns carrying the massive cross through the streets.3 Once the massive cross had circled through the city and returned to the cathedral, it was hoisted upright. The crowd filling the square, adjoining streets, and every available balcony, window and rooftop then bore witness to a passionate sermon, which climaxed in a mass cheer: “Long live Jesus! Long live the cross! Long live the king!”

A cross-planting procession in Reims, 1821. Artist unknown. Missionary leader Charles de Forbin-Janson rides on top of the crucifix, guiding it through the town — something he actually did, to help the giant 64-foot cross navigate the city’s narrow streets. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France

This is The Siècle, Episode 27: Mission from God.

It’s been a while, hasn’t it? Nothing bad has happened to me, just a mix of procrastination and a big, complex tangle of a topic. Religion is tricky — who knew?

You just heard Bry Jensen of the Pontifacts podcast reading the cold open, a look at one of the most dramatic set-pieces of the Bourbon Restoration: the revival missions trying to bring the Catholic Church back into the lives of her wayward French parishioners.

The 1818 mission in Clermont was just one of hundreds of similar missions held across France during the Bourbon Restoration. They were among the most prominent and public symbols in the period of the traditionalist side of the Restoration monarchy — the efforts to restore the pre-Revolutionary union of throne and altar.

But not everyone joined a mission choir or hauled a giant crucifix through town. France in the Restoration was a complex religious tapesty. There were plenty of Jews and Protestants as well as Catholics. Many people were effectively a-religious or outright atheist. Even within the Catholic Church, a host of different factions and orders disagreed with each other about the best way to bring France back to the Church.

It’s that full religious picture that we’re going to explore today. Not only is religion vital to fully understand France at this time, it’s especially vital to understand the new King Charles X.

“Complete ignorance of its Christian duties”

Most of the roughly 30 million French people in 1815 were at least nominally Catholic. I haven’t been able to find any specific numbers on exactly what share of the French were practicing Catholics circa 1815, but contemporaries often took a dim view of the state of French souls. In 1826, the pope’s representative to France lamented that, “More than half the nation is in complete ignorance of its Christian duties and is plunged into indifference.” It was particularly bad in Paris, he went on, where “hardly an eighth of the people go to church, and one can wonder whether there are as many as ten thousand men in the capital who practice their religion.”4

Not everywhere was as secular as Paris, but this wasn’t just a city-versus-country affair. There were plenty of areas where peasants had stopped going to church, too. Vast swathes of northern France were effectively dechristianized, with pitifully few people attending church even once per year for Easter.5 On the other hand, in more religious areas like some southern or western departments, as many as 90 percent of people attended Easter Mass.6

The declining importance of Catholic religion for France can been in all sorts of areas. Contemporary polemicists lamented the “astonishing immorality” they found in French town after town, such as the northwestern town of Le Mans where a missionary claimed, “the young people are lost.”7 The decline of religion, from young people who had never been confirmed or even baptized to couples who had been married outside the church, was widely blamed for a whole host of “immoralities” such as allegedly rising incidents of drunkenness and premarital sex.8

But the decline of Catholicism was not just a question of he-said, she-said. There are plenty of hard statistics that testify to the diminished significance of the Church to daily life. For example, consider the share of marriages taking place in December and March — dominated by the holy seasons of Advent and Lent. Before the Revolution, these December and March weddings were extremely rare, just 3 percent of all ceremonies. In the 1820s, when fewer people cared about these holy seasons, 7.5 percent of weddings were held in these months.9 (That is, if you’re doing math quickly in your head, much less than the 16.7 percent that would be an equal share, but still more than twice as high as before.) You can also discern this rising secularism in the number of people who were working on Sundays — despite the fact that the Restoration made this illegal.10

Still, if it sometimes seemed to contemporaries like France was completely dechristianized, we shouldn’t overstate affairs. The Catholic Church retained a major institution for daily French life. Even people who never attended Mass would usually have their children baptized, and most kids would make their first communion — even if many never attended again after that milestone.11 France hadn’t become secular, but it had become more secular.

So what was to blame for this relatively irreligious state of affairs?

The obvious answer is the French Revolution, which devastated the Catholic Church. The Revolution confiscated all the Church’s property, executed thousands of clergy and drove tens of thousands more into exile.12 New recruitment for priests dried up. Ancient privileges were stripped away from the Church, removing countless areas where the Church had been interwoven into the fabric of French life. There was an entire generation where many Frenchmen got used to what was once unthinkable: life without the Church.13 And even though the Bourbon Restoration eventually came around to try to bring some of these privileges back, it was unable or unwilling to change the new status quo, in which “religion had become a private option rather than a public obligation.”14

But while the Revolution was undeniably disastrous for the Catholic Church as an institution, we shouldn’t over-credit it for the changes in French religiosity — though it certainly contributed! Many of these declines in churchgoing were visible long before the fall of the Bastille. Across the 18th Century, births outside of marriage rose, as did the share of pregnant brides — both of those factors suggestive of the church’s teachings on sex and marriage having less of an impact. Recruitment to the priesthood fell by 23 percent in the half-century leading up to 1789. In the region of Provence, 80 percent of the deceased had requested masses be said for their souls in 1750, but this was down to 50 percent in 1789.15 Clearly there was something broader at work.

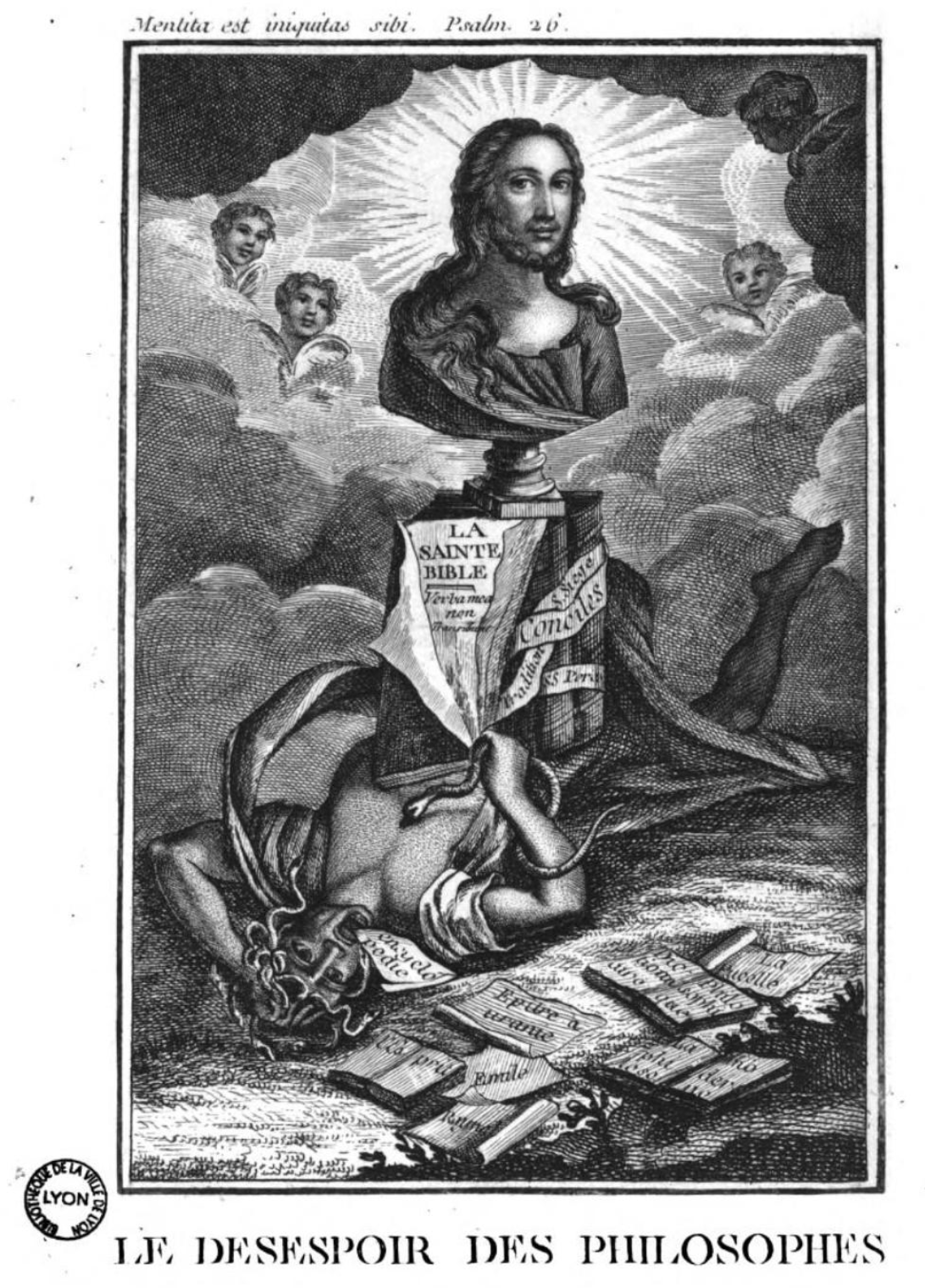

Some contemporary Catholics believed a primary culprit were Enlightenment writers like Voltaire and Diderot, whose works were seen as skeptical, atheistic and anticlerical — and, they argued, the ultimate intellectual source of the political upheavals that overturned the Old Regime in 1789.16 The counterrevolutionary thinker Joseph de Maistre contrasted Voltaire with the radical Jacobin Jean-Paul Marat: “This Voltaire whom blind enthusiasts transported to the Pantheon is perhaps, in the judgment of God, guiltier than Marat. For it is likely that Voltaire made Marat, and it is certain that he did more evil than him.”17

Some contemporary Catholics believed a primary culprit were Enlightenment writers like Voltaire and Diderot, whose works were seen as skeptical, atheistic and anticlerical — and, they argued, the ultimate intellectual source of the political upheavals that overturned the Old Regime in 1789.16 The counterrevolutionary thinker Joseph de Maistre contrasted Voltaire with the radical Jacobin Jean-Paul Marat: “This Voltaire whom blind enthusiasts transported to the Pantheon is perhaps, in the judgment of God, guiltier than Marat. For it is likely that Voltaire made Marat, and it is certain that he did more evil than him.”17

But these philosophes had not merely committed their terrible crimes in the past. They were, many Catholic writers argued, still committing them from beyond the grave. Perhaps surprisingly, the Bourbon Restoration took no action to stop the publication of millions of new copies of Voltaire, Rousseau and others, rolling off the shelves in — maybe the scariest part — increasingly cheap editions that even peasants and workers might be able to afford.18

Above: “The Despair of the philosophes,” in which “Christ reigns supreme over a vanquished medusa, who vomits up the Encylopédie, Rousseau’s Émile, Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique, and other key Enlightenment texts.”19 From Élie Harel’s 1817 Voltaire: Particulaires curieuses de sa vie et de sa mort, an anti-philosophe text. Public domain via Google Books.

The overlooked non-Catholics

Whatever the state of French Catholicism, it was beyond a doubt the nominal religion of “the great majority of Frenchmen,” to use a loaded phrase I’ll get back to shortly. But it wasn’t the religion of all Frenchmen. In particular, France had significant minority communities of Protestants and Jews, both of which had only received formal legal recognition with the French Revolution. Despite some worries, Louis XVIII had ratified this recognition with the 1814 Charter of Government, which declared in Article 5 that, “Everyone may profess his religion with equal freedom, and shall obtain for his worship the same protection.” But as we’ll see, legal equality, while profoundly welcome, only went so far.

France in the Bourbon Restoration had perhaps 500,000 Protestants, of whom about half were Lutherans living in Alsace. The rest were more spread out, and included many Calvinists — also known as “Huguenots.”20 We’ve already met one such Huguenot community, in the southern department of the Gard, locked in a bloody tit-for-tat struggle with their Catholic neighbors, back in Episode 5: The White Terror.

Overall, Protestants’ situation had been drastically improved since the Revolution. Before 1789, Protestants had been legally persecuted. The law even put recording births and marriages in the hands of the Catholic Church, leaving French Protestants forced to either “compromise their faith, emigrate abroad, or live in legal limbo.”21 As the Marquis de Lafayette put it in 1785, “Protestants in France are under intolerable despotism. Although open persecution does not now exist… it depends on the whim of king, queen, parliament or any of the ministers. Marriages are not legal among them, their wills have no force by law, their children are to be bastards, their parsons are to be hanged.”22

All this had been abolished, and the Charter had confirmed the legal equality of Catholics and Protestants. But this didn’t mean that Protestants had social equality. Many Catholics, from peasants in the Gard to top government ministers, treated Protestants with hostility. Ultraroyalists often saw their great ideological enemy, liberalism, as little more than “political Protestantism” and traced the origins of the hated French Revolution all the way back to Martin Luther.23 In 1827, the minister of public instruction and ecclesiastical affairs wrote to the interior minister about “the grave consequences of giving too much protection to a form of worship opposed to the state religion.”24 But there were socially prominent Protestants in the Restoration, of whom the most notable is probably François Guizot, a popular professor and historian who served in several significant government positions under Élie Decazes before moving into the liberal opposition after 1820.25

There were also perhaps 60,000 Jews in France, in three major communities. One group lived in the area around Avignon in Provence, which had been ruled by the popes until the French Revolution. In generations past, the popes had offered more protection to Jews than they could find in the rest of France. Another community lived in southwestern France in cities like Bordeaux and Bayonne; their ancestors had fled there from Iberia. A third group lived in the German-speaking areas of Alsace. It’s this community from which the ancestors of Alfred Dreyfus were living at this time.26 There was also a small Jewish community in Paris of a few thousand. But it was divided between Jews of German, Portuguese and Provençal extraction, speaking different languages and worshipping in different synagogues.27

Even setting aside social discrimination, Restoration France had some forms of legal discrimination against non-Catholics, and in particular Jews. For example, in 1808, Napoleon had enacted the so-called “infamous decree” that restricted the ability of Jews to lend money, required them to get a license to engage in commerce, and barred them from moving to Alsace. The decree was enacted with a 10-year timespan, and after Napoleon’s fall the Bourbons continued to enforce this decree until letting it expire in 1818. Jews were also required to swear a special oath in courtrooms, the so-called “more judaico.”28 The Restoration government paid the salaries of Protestant pastors as well as Catholic priests, but not Jewish rabbis.

There’s a stereotype to imagine that all French Jews were financiers and all Protestants were industrialists, but in practice the two communities appear to have mirrored the social composition of France as a whole, though Jews increasingly lived in urban areas while Protestant populations were more rural. Around this time, we’re told, France’s Jewish population was classified as 17 percent bourgeois, 18 percent indigent, and the rest varying degrees of workers, shopowners, and the like.29

Hellfire and brimstone

As a final bit of background, I’d like to touch on two areas where the Restoration saw the early stages of significant religious transformations that would continue and accelerate over the course of the 19th Century: evolving theology, and an increasing gender divide over religious attendance.

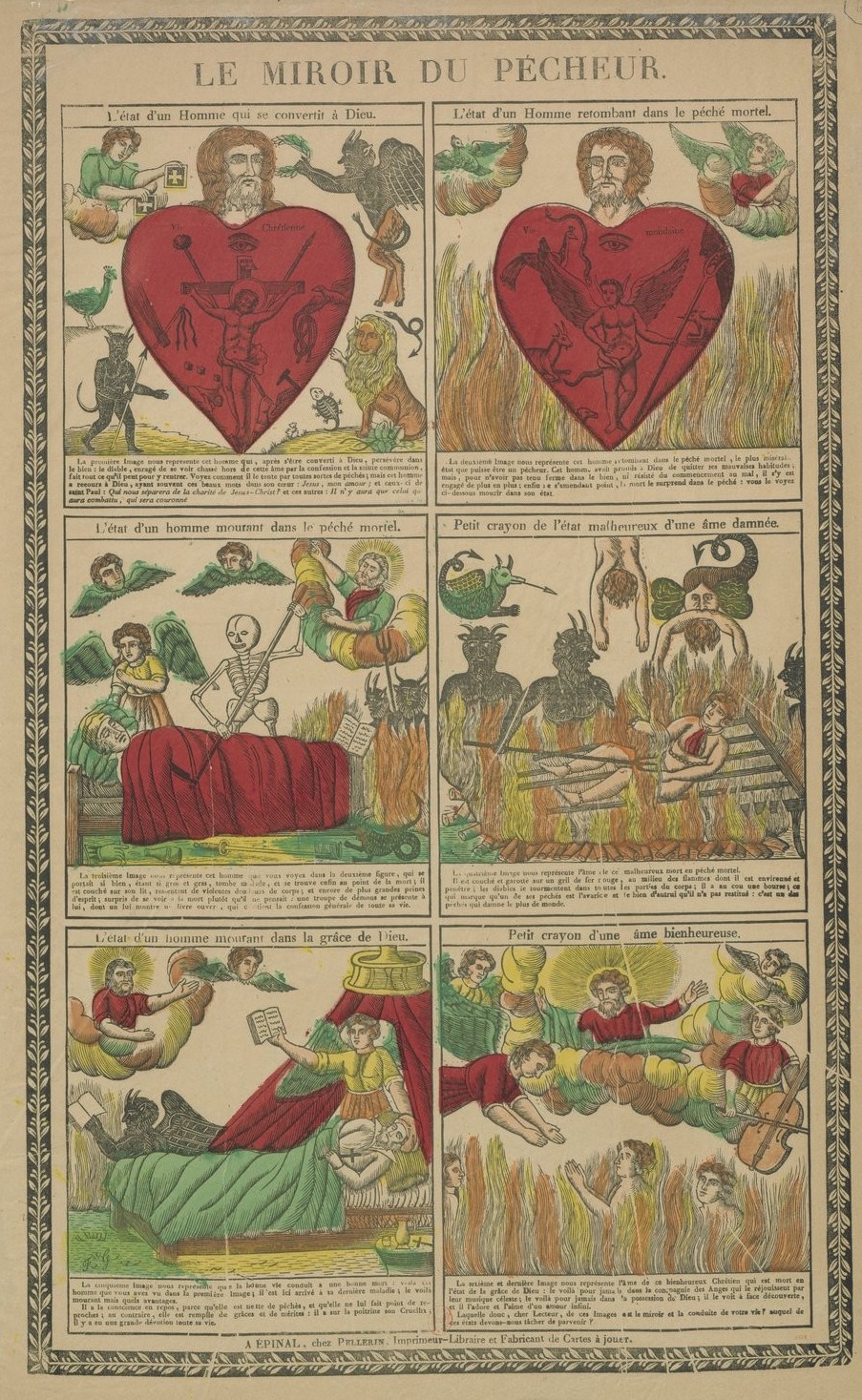

The stereotypical message French Catholics had heard from priests in the 18th Century was intense and dark, visions of hellfire intended to bring the fear of God to parishioners. That’s not to say priests never preached about a “God of mercy,” only that a “God of justice and even vengeance” was more common. And that appears to have held true into the period of the Restoration, though changes were slowly brewing.30

The stereotypical message French Catholics had heard from priests in the 18th Century was intense and dark, visions of hellfire intended to bring the fear of God to parishioners. That’s not to say priests never preached about a “God of mercy,” only that a “God of justice and even vengeance” was more common. And that appears to have held true into the period of the Restoration, though changes were slowly brewing.30

Starting in the 1820s, different perspectives started to gain steam in France, ones that urged a softer, more sympathetic tone from a priest to his flock, to inspire them with hope rather than fear. This process took time, and maybe have taken root sooner in the cities than the countryside, but by the second half of the 19th Century there will be a profound qualitative difference in the tone French priests take from the pulpit.31

An example: A typical sermon from the first half of the 19th Century describes a family’s reunion in the afterlife — in Hell, where parents are assailed by their children for failing to provide a good example and spare them from eternal damnation. By the second half of the century, the idea of dead children burning in hell had basically disappeared in favor of sermons about them being angels in Heaven.32

That said, while French priests maintained an 18th Century emphasis on doctrinal rigor in the Bourbon Restoration, this struck many of their parishioners as a new development. That’s because the disruptions set loose by the Revolution had left many of them without priests for a generation, trying to live their faith as best they could. Now, the return of exiled priests alongside a pro-clerical political regime meant many people were suddenly faced with a host of requirements to gain access to religious sacraments. It was a rigorism — or, to its critics, a “fanaticism” — that “seemed extremely harsh to people who had for many decades developed their own way of practicing Catholicism in the absence of priests.”33

At the same time, styles of preaching were becoming less formal and more naturalistic.34 Abandoning pre-revolutionary habits of ignoring their critics, Restoration pastors increasingly addressed skeptical arguments directly from the pulpit. In the words of Abbé Denis Frayssinous, the most famous preacher of the day: “The doctor surely must adapt his remedies to the needs, to the constitution of the patient. Such is the current malady of the spirit that one can only effect a cure by adopting a new method.”35

I should also note that many of the doctrinal upheavals that were affecting Catholicism during this era of Romanticism also impacted French Protestantism. This was the era of the “Second Great Awakening” in the United States, and Europe saw its own theological tumults. I won’t go into detail about these changes and disputes here, but suffice to say this was a lively period in French Protestantism, rife with new movements, doctrinal disputes and active societies for evangelism and social work.36

Above: François Georgin, “The Sinner’s Mirror,” 1830. This print contrasts the fate of someone who dies in a state of sin versus a state of grave. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France

The gender gap

There were also important gender differences, with women being much more likely to be religious than men. In the strongly religious Vendée region, women made up about 60 percent of all parishioners at mass; in the much less devout Paris, the ratio was an astounding 10 women to every 1 man.37 This gender gap had existed back in the 18th Century, had been widened during the Revolution when when devout women resisted secularization efforts,38 and by the Restoration was readily apparent. The ranks of female religious orders boomed in the years after 1815, with groups like the “Sisters of Charity” or “Daughters of Wisdom” devoting themselves to charity.39 The split was even visible at the highest levels of society, where it was not unusual for thoroughly secular and irreligious men to nonetheless consider piety an appropriate virtue for their wives and daughters.40

Why was there this huge gender gap in French religiosity? People at the time had their own answers, often based on then-current ideas about the essential natures of men and women. The contemporary anticlerical historian Jules Michelet would blame “women’s greater religiosity on their naturally docile susceptibility to clerical authority”41; church officials inverted this essentialism, praising “the wife who, by her gentle and tender piety, perpetually calls back to God those who forsake Him.”42 More recent scholars have noted how women in 19th Century France faced many limitations about their participation in the nation’s public life; the church, while hardly egalitarian, offered women opportunities for socialization and service in addition to worship.43 Or alternatively perhaps it was not so much women being drawn to the Church as men pulled away from it, whether by a masculine culture that sometimes scorned priests as weak or feminine,44 or by more practical matters like boys increasingly learning from secular teachers while many girls, if they were educated at all, went to religious schools. In the Restoration in particular, many men had had a formative experience serving in the thoroughly secular armies of the Republic and Empire.45 As late as the 1860s, girls were nearly three times as likely to attend church schools than boys.

King and Pope

Against this backdrop, the restored monarchy of King Louis XVIII tried to exert itself. Louis, though not as overtly spiritual as his younger brother Charles, was committed to the Catholic Church as one of the cornerstones of France and his regime.46

The Restoration’s first major action here came with Louis’s Charter of 1814, which contained three key articles concerning religion. I’ll read them to you verbatim:

Article 5: Everyone may profess his religion with equal freedom, and shall obtain for his worship the same protection.

Article 6: Nevertheless, the Catholic, apostolic and Roman religion is the religion of the state.

Article 7: The ministers of the Catholic, apostolic and Roman religion and those of the other Christian sects alone receive stipends from the royal treasury.47

You can see the needle Louis was trying to thread here. On the one hand, he conceded one major reform from the French Revolution: freedom of religion. It would not be illegal to be Protestant, Jewish, atheist or anything else in the Bourbon Restoration.

On the other hand, the Catholic Church was declared “the religion of the state.” That’s a significant phrase crafted with great care and deliberation. To understand why, we need to go back to 1801, when First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte negotiated a so-called “Concordat” with Pope Pius VII, setting out the relations between Church and state in post-Revolutionary France. The full details of the Concordat are beyond the scope of this podcast, but suffice to say they represented something of a compromise: restoring a legal role for the Catholic Church in France after years of revolutionary persecutions, but also giving Napoleon significant control over the French Church. Of most immediate concern, the Concordat had declared Catholicism “the religion of the great majority of French citizens.”

Right: Thomas Lawrence, “Pope Pius VII,” 1819. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

That distinction — “the religion of the great majority of French citizens” versus “the religion of the state” — gets at a core definitional issue: was Catholicism a fundamental part of what it meant to be French? Or was it merely a trait shared by most French people, like preferring wine over beer? Depending on your views on Catholicism, religion, tradition and liberalism, this was a very serious question indeed.

But the first major religious struggle of Louis’s regime came not against secular liberals, but with the Pope. Among his earliest actions, in the summer of 1814, Louis dispatched an envoy to the Vatican to negotiate a new agreement between church and state in France. This would have replaced Napoleon’s Concordat, which both Louis and Pope Pius VII hated.48 But agreeing on a replacement was easier said than done.

For example, Pius’s desire to replace the Concordat was temperated by the fact that he was the one who approved it in the first place, back in 1801. Dumping it out too brusquely could make him look bad. So Louis’s initial demand was to revert back to the status quo of 1789 — removing all the sitting bishops who had been appointed since then. That would have purged 14 Napoleonic or ex-revolutionary bishops. But doing so would have been an admission that the Concordat had been invalid, which Pius couldn’t bring himself to do.49

As a result, these negotiations dragged on and on. Despite starting almost as soon as Louis retook the throne in 1814, they weren’t yet done in spring 1815 when Napoleon returned for the Hundred Days. After Waterloo, talks didn’t resume in earnest until 1816, when both sides started to make concessions. Louis agreed to no longer insist on disavowing the Concordat; the pope received statements of submission from the remaining ex-revolutionary bishops that satisfied his demands.

And then, of course, everything blew up again. First Louis insisted on appending a statement endorsing the historical “liberties” of the French Church from the papacy, which caused the pope to back out. Once the long-suffering diplomats smoothed that over, it was the turn of the French parliament to object that the deal was allegedly too friendly to the pope. When all the dust settled, the two exhausted sides agreed to just give up and maintain the old Napoleonic Concordat, with some tweaks to gradually create new bishoprics. By 1822, thirty additional bishoprics were set up, resulting in 80 different dioceses that largely correspond to France’s civil departments — a structure that largely holds to this day.50

Ultramontanes and Gallicans

That whole futile circus just goes to underscore how complicated questions of religion could be in Restoration France. You had splits between Catholics and non-Catholics, and between conservatives and liberals. There was also the split between so-called “Ultramontane” Catholicism, which emphasizes the primacy of the pope, and “Gallicanism,” which focuses on the rights of the state and local bishops to govern a country’s church.

One example highlights all these intricate divisions inside the question of religion in Restoration France: the Jesuits. This controversial religious order, with a focus on education and evangelism and an oath of obedience directly to the Pope, had been suppressed in the 18th Century and restored in 1814. The order’s supporters saw them as “the natural and necessary champions of counter-revolution,” whose discipline and facility with argument and education could counter the philosophes and Freemasons seen as bolstering the secular left. They were in turn seen by the left as a sinister cabal, subject of a thousand conspiracy theories — a sort of mirror image to how the right often saw Freemasons. But even on the right, the Jesuits had enemies, including a movement called the “Jansenists,” who urged a severe, rigorous approach to faith. The Jansenists saw the evangelizing Jesuits as softening and twisting core Catholic doctrines to try to make them palatable for mass audiences, and bitterly attacked the Jesuits from the right as quasi-heretical.51

I’ll have more to say about the Jesuits and their opponents down the road. At the death of Louis XVIII, anti-Jesuitism existed in France but was a relatively small movement. It won’t stay that way.52

Championing the Church

As we’ve seen, Louis XVIII was highly sympathetic to the Catholic Church — but still protective of his own authority over the French Church. One advisor wrote that “the surest way to Louis XVIII’s heart [was] in considering religion as a means of government.”53 And indeed, though there’s a stereotype casting Louis as a skeptic and his brother Charles as a fanatic, that is unfair to Louis, who attended Mass almost every day and repeatedly expressed interest and concern for the Church and the faith of his subjects. There’s no indication, his biographer Philip Mansel concludes, that Louis was not a “believing Catholic” — but it is also “doubtful if Louis’s faith went very deep. It did not pervade his whole life, giving him strength and courage to wear his earthly crown, as it did with Louis XVI.”54 Charles, as we’ll see in future episodes, clearly had a deeper-seated faith, even if his faith and his Louis XVIII’s were not as different as many people believed.

But Louis championed the cause of the Church in numerous directions. Especially in the first two years of the Restoration, a number of pro-Church laws were passed: divorce was abolished; bishops were given the authority to open religious schools; a law promoting gifts to religious institutions was passed; another law forced public establishments to close on Sundays. Abbé Frayssinous, the bishop and famed preacher I mentioned earlier, was appointed Grand Master of the University of France, and began pushing out anti-religious teachers in favor of ecclesiastics. To combat a crippling shortage of priests, the government doubled priestly salaries, built new seminaries and endowed new scholarships; as a result the number of yearly ordinations more than doubled and the average age of the French priesthood went down.55

However, by far the most conspicuous, and controversial, efforts to promote Catholicism under Louis’s reign were revival missions like the one Bry described at the top of the episode.

Missions to the interior

The missions kicked off in a somewhat roundabout way. A priest named Charles de Forbin-Janson traveled to Rome for an audience with the pope, where he expressed a desire to work as a missionary in China. But the pope replied that “it is necessary first to offer our aid to the populations which surround us,” and sent young Forbin-Janson back to France, where he promptly signed on to a group that was soon incorporated as the “Missionaires de France,” or Missionaries of France. This project had the explicit backing of Louis XVIII, who gave it legal status, his blessing, and helped subsidize it from his personal funds. Another major group of missionaries consisted of Jesuits, though their royal backing was more circumspect and came with explicit commands to present themselves “not in the name or the habit of their order.”56

With royal backing secured, the missions began, starting with a revival in the city of Orléans in late 1815.57 Over the next 15 years, more than 1,500 missions of various sizes would be held around France, in almost every part of France.58 The details of each mission varied, depending on the funds raised to pay for the mission, the quality and fame of the preachers leading it, and the friendliness of the town and local authorities to the missionaries. But the general order of events was pretty standard, drawing on a long history of mission activity.

First, the missions were led by outside preachers. A city’s local clergy were perfectly capable of staging a revival, of course, but in practice it was outside specialists who were brought in to bring God back to a given town — especially because so many dioceses were extremely understaffed after decades of privation.59

Before the mission even began, fundraising and promotion would have been going on for months, and one or more missionaries might arrive early to organize a choir so they’d be ready to perform at the opening procession.60 That majestic opening procession would kick things off on a Sunday, leading to an initial sermon that evening. The next day would begin a daily routine of religious instruction — often services before dawn and after sunset in working-class parishes, and during the day in richer parishes whose affluent residents could take off work to attend.61

In between these daily sermons, each mission would typically be built around five great ceremonies. These included a renewal of baptismal vows, and a consecration to the Virgin Mary, as well as two more dramatic ceremonies: the planting of the mission cross, and the amende honorable, a sometimes uncomfortable penitential service in which attendees sought public forgiveness for their sins, and were encouraged to forgive others. Finally, there was a general communion; getting lapsed Catholics to return for Communion was the ultimate goal of the mission. In between there would be other special events, such as a men’s retreat, a Mass for the dead, and confirmations.62

The entire mission would typically last six to seven weeks and involve hundreds of sermons and services, attracting thousands of participants for a series of high-visibility ceremonies.

But that still leaves the big question: did they work? Did these elaborate and expensive internal missions actually bring large numbers of people back to the Catholic Church?

The short answer appears to be a qualified “yes.” But the long answer is much more complex.

Ascertaining precise answers like this in an era before scientific polling or other metrics we have today is always going to be an uncertain proposition. It gets even murkier when you combine that with the fact that most of our witnesses to these events were partisans of one side or the other, and can’t necessarily be relied upon.

Nonetheless, there are some reasonable conclusions we can draw from the available records.

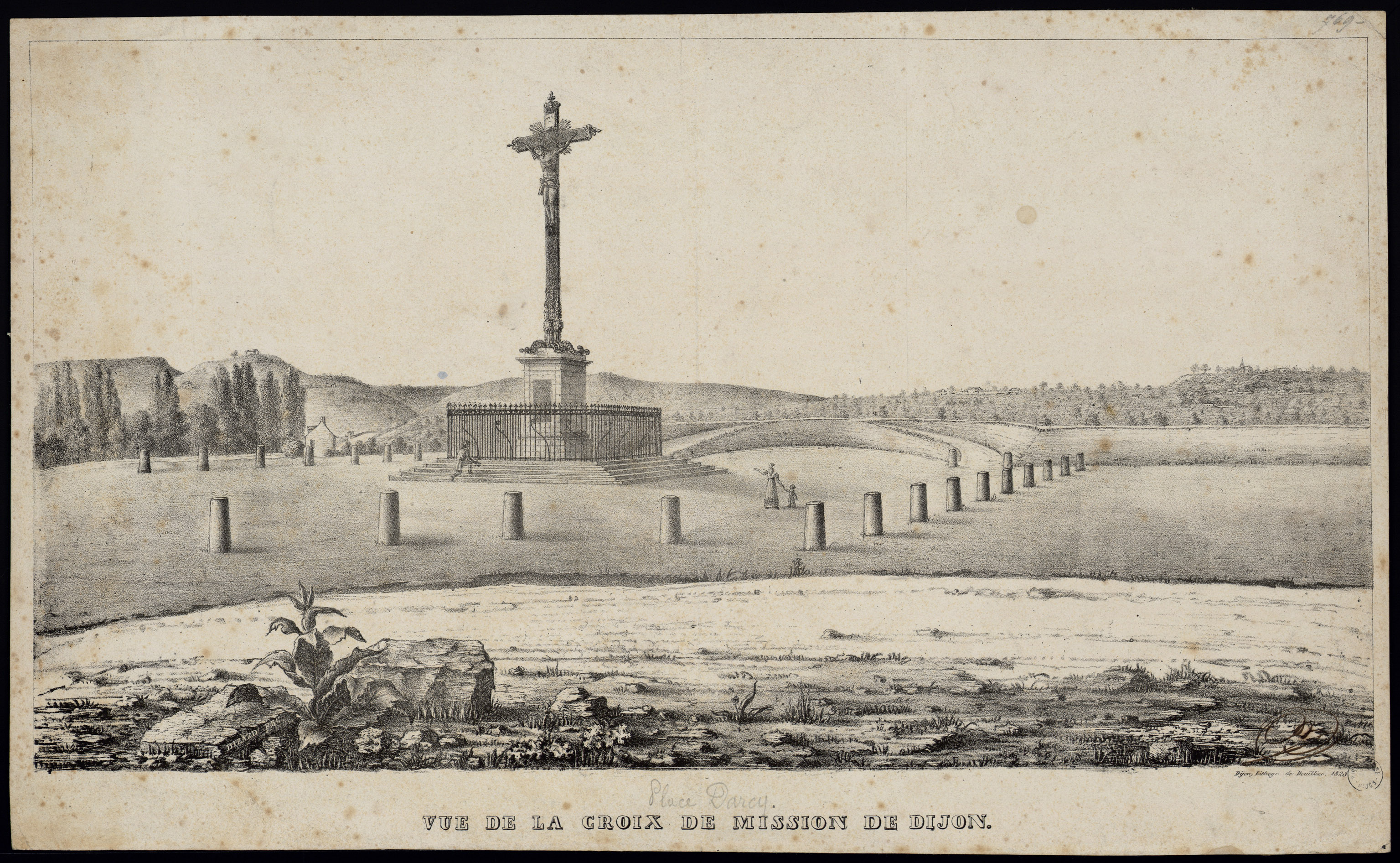

Representation of the mission cross in Dijon, elevated Oct. 12, 1821. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France

The missions as a success

First, these missions do seem to have genuinely touched many thousands of attendees. Consider the story of one Julien Cottier, a real man and avid revolutionary who had sentenced people to death on a tribunal in the Reign of Terror. After attending a mission, Cottier renounced his past, promised restitution for his victims, and performed a public act of devotion. More than 20 years later, a priest reported Cottier was still a faithful Catholic.63

There are countless similar stories in the voluminous accounts of the missions that evangelists published. Even if you dismiss many of these conversion stories as made-up, exaggerated or credulously accepted by these pro-mission writers, the evidence is strong that there were a considerable number of Julien Cottiers out there. Not all of them may have had Cottier’s dramatic swing from Jacobin to Catholic, but for thousands of French men and women the missions lit the flame of belief. Even critics of the missions admitted as much, with one liberal paper in Marseilles denigrating the priests as “‘sacred jugglers,’ whose ‘profane pomp’ had succeeded in ‘seducing’ even the well-educated population, who should have known better than to fall victim to the trickery of ‘imposters’ and ‘hypocrites’”64 — a sort of backhanded tribute to the missionaries’ effectiveness!

The crowd sizes, and their intensity, also can’t be ignored. You’ve already heard about the passion that could come out for the great mission-cross ceremonies, which were usually the most visible aspect of the missions. But even less dramatic moments could inspire frenzy. Many ceremonies were standing room-only; in one city there were so many people we’re told the missionaries had to “clamber over men’s shoulders to reach the pulpit.” In Marseilles, a group of around 200 women rushed into a church late in the evening, right before it was locked up, intending to spend the night there to get a head start on the morning’s service. After they were persuaded to leave, the women spent the night waiting outside the church despite a cold rain.65 When missions were over, “missionaries frequently rode out of town on a wave of popular esteem, with adoring crowds following them along the roads for miles.”66

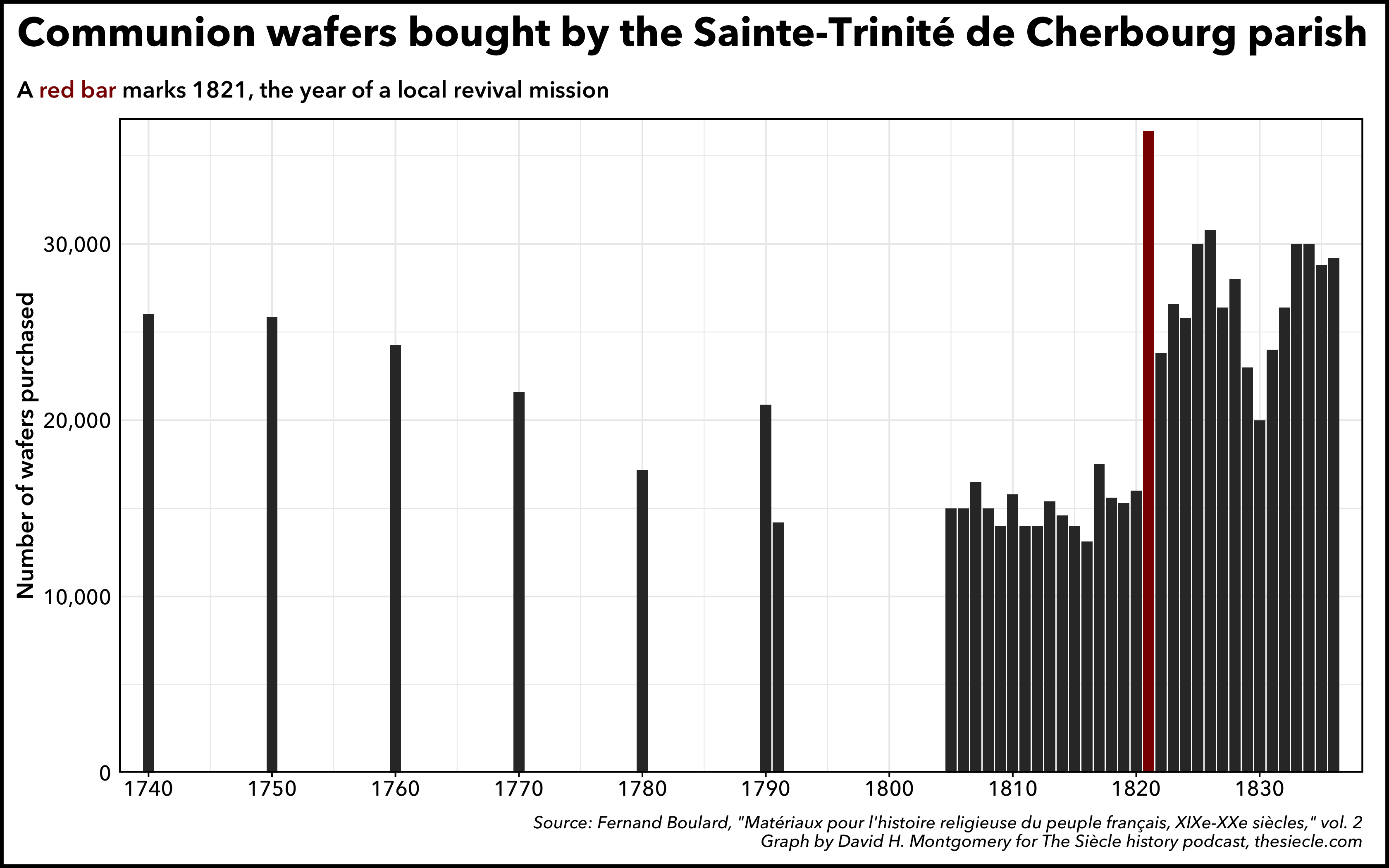

In at least one case, we have concrete numerical evidence for the impact of the missions. The parish of Sainte-Trinité in Cherbourg has maintained records showing the number of communion wafers they purchased most years, dating all the way back to the 18th Century. Before the Revolution, this parish tended to buy more than 20,000 wafers per year, but starting in 1791 this fell to below 15,000 and stayed in that area throughout the years of Napoleon and the first part of the Restoration. But in 1821, when the area hosted a mission, the number of wafers purchased more than doubled, to around 36,400. This total fell a bit in subsequent years, but never so low as it had been before the missionaries came to town.67 Post-mission, more people in this little parish were taking Communion, and there’s no reason to believe it was an anomaly.

Another scholar has calculated that on average, a mission would result in 250 to 300 men returning to communion in each of the 84 départements where missions took place, as well as twice as many women. If you multiply that out, you get something like 75,000 new converts nationwide, or about a quarter of 1 percent of France’s population of around 30 million. 68 On top of that you have to add untold numbers of currently observant Christians who became more fervent in their beliefs.

Backlash

But while these missions definitely had their successes, this success also needs to come with major qualifications. In particular, these missions landed like a ton of bricks right in the middle of Restoration France’s raging culture war, where many people were fiercely anticlerical, or saw these Catholic revivals as stalking horses for Ultraroyalist politics. When missions arrived in towns, they were met by throngs of worshippers, yes, but also protesters and hecklers.

The mission to the city of Brest in Brittany, for example, saw thousands of protesters show up outside the local bishop’s residence, screaming “No mission! Down with the missionaries!” Meanwhile more respectable critics of the mission pressured the city council. After three days of demonstrations, the bishop caved and ejected the missionaries from town.69

Brest was the only place where protesters actually succeeded in blocking a mission,70 but elsewhere they repeatedly disrupted and mocked the carefully planned evangelical spectacles. In many cities prostesters blanketed the city with anti-missionary placards, sometimes parodying official pro-mission posters in form or language.71 Anti-clerical pamphlets were widely circulated, and liberal newspapers gleefully reported every occasion where a mission was disrupted.72 Youths set off firecrackers and stinkbombs in the middle of church services. In the town of Dieulefit several young men barricaded the worshippers in the church, then urinated on the recently erected mission cross.73 A peasant named Monsieur Bourreau got drunk one night and ranted at his town’s mission cross: “Pig of a Good God. Come down from up there! So I have to pray to you! You have an ugly black moustache.”74 Missionaries were frequently hung in effigy, and in one extreme case a hapless priest was set upon and stripped naked in public; he required an armed escort to safely leave town.75

Perhaps the most innovative way that anticlerical French men and women protested the missions — and Catholic priests more generally — was at the theater. When a mission was coming to town, historian Sheryl Kroen has chronicled, mobs would often descend on the local theater with a demand: instead of their planned performances, the actors needed to put on Molière’s classic comedy Tartuffe. This was a pointed request — the plot of Tartuffe concerns the titular schemer who pretends to be religiously devout in order to seduce a virtuous woman. In the context of Restoration France, demanding a Tartuffe performance was a way to criticize religion as hypocritical through the unimpeachable cover of one of the greatest writers in French history.76

If the actors obliged and performed Tartuffe, the local anticlerical faction would swarm the theater and applaud some of its more pointed bits of dialogue “with a bit more applause than was customary,” as one government official put it.77 If the actors tried to perform another play, audience members would disrupt the performance, throwing things or loudly chanting, “We want Tartuffe, nothing but Tartuffe.”78 If the actors resisted — or, more accurately, if local officials resisted — these episodes of so-called Tartufferie could spill out into the streets for weeks of protest. One high-profile Tartufferie incident in Rouen in 1825 began on April 18 and persisted through weeks of protests until May 6, when Tartuffe was finally performed after no less than King Charles X intervened to authorize the performance. 79 Police often blamed these disruptions on local bourgeois liberals, who certainly cheered them on, but in most cases incidents of Tartufferie appear to have been driven by working-class theater-goers.80

I could talk far more about this fascinating campaign, but in the interests of time I’ll just recommend you check out Sheryl Kroen’s book Politics and Theater: The Crisis of Legitimacy in Restoration France. You can find a link to buy that book at thesiecle.com/episode27.

Understanding Restoration anticlericalism

So why did the missions provoke such hostility?

Some of it was simple and straightforward: irreligious people who didn’t like their county’s dominant religion and especially didn’t like it being shoved in their faces. Even in the present day, there are lots of people who are actively anti-religious.

But the full explanation goes beyond that. Whatever influence religions have in modern Western democracies, the Catholic Church in the Bourbon Restoration was many times more influential and important. It was inextricably bound up in questions of both politics and social life.

French liberals, for example, had very good reasons to resist the missions. The missionaries were not politically neutral, but often explicitly preached counter-revolutionary and ultra-royalist doctrines.

Among the “sins” that people were asked to repent in the amende honorable, for example, was having purchased church property during the Revolution81 — the so-called biens nationaux that I talked about all the way back in Episode 1, which up to 10 percent of the population had purchased.82 When I mentioned that agitation for the return of the biens nationaux was one of the factors undermining the Bourbon regime, this is the kind of agitation I’m talking about.

The biens nationaux weren’t the only aspect of the Revolution that missionaries took aim at. Another sin they said needed to be atoned for was having served in the armies of the Revolution or Napoleon. Missionaries told many couples that their longstanding marriages were in fact illegitimate because they had been performed under a revolutionary regime, that their children were bastards in the eyes of God unless they remarried under legitimate priests. Those striking mission crosses were often raised explicitly on sites where revolutionaries had planted a liberty tree or where a guillotine had operated — a deliberate attempt at “reconsecrating the landscape.”83

And remember how many Catholics saw the writings of Enlightenment philosophers as pernicious and evil? Well, the missionaries put this into direct action with some spectacular book-burning ceremonies, in which people were encouraged to bring forth any heretical writings they might own to be publicly consumed by fire. Some even excommunicated anyone who owned works by the like of Rousseau but didn’t bring them forward for public destruction. (I should note these book-burning ceremonies did not appear to dent the enthusiasm with which new editions of the philosophes were printed and purchased; one publisher cheekily advertised a fireproof edition of Voltaire. Perhaps more successful than the book-burnings was a parallel campaign to produce and distribute Catholic texts, “good books” to counter the bad.84)

Unknown artist, “Le phénix renaissant de ses cendres,” or “The phoenix rises from its ashes,” depicting a book-burning ceremony of philosophic books, while the phoenix of philosophie rises reborn from the flames. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

More deeply, the theology of the missionaries set forth a fundamentally different model of political authority than those coming out of Revolutionary and Enlightenment thought, one based on divine right instead a contractual relationship with the people. Restoration liberals didn’t need to be directly threatened by the missionaries to perceive a threat to their conception of how government worked.85

But even less political people often had good reason to resent the missions. Missionaries preached against a host of common popular practices as sinful. Many otherwise indifferent people found themselves incensed at clerics who preached about how singing, dancing and drinking were sins. Sometimes missionaries hosted a retreat for the young women of a community, in which the women were asked to swear to give up dancing. As historian Martin Lyons notes, “Nothing was likely to infuriate the young men of the village more than this approach.” 86 Missionaries criticized reading novels and the pleasures of cabarets and cafés, and lambasted the theater — even when Tartuffe was not being performed. To these abstract criticisms were added very real disruptions: missionaries usually tried to get cafés and cabarets closed and theater seasons suspended for the duration of the mission.87

These clashes with popular culture were not accidents that the missionaries stumbled into, but very deliberately chosen. For example, missions were often scheduled to overlap with — and thus preempt — the riotous festival of Carnival. This not only threatened what to many people was one of the highlights of the year, it also threatened the livelihoods of many workers and small businesses who catered to the festivities. A group of bakers in Marseilles, for example, submitted a petition against their city’s 1820 mission, urging the missionaries to “cast a sympathetic glance at our young boys whose sales for the carnival season represent their annual salary.”88

The government, caught in between

These critiques of the missions did not find deaf ears among public officials, despite the open support the Bourbon regime gave to the missions. Prefects and police commissioners might have been all for the re-Christianization of their communities, but they were firmly against protests, riots and public discord, all of which the missions seemed to provoke.

Louis XVIII’s regime had an official policy of “union et oubli,” or “unity and forgetting” — trying to let bygones be bygones and focus on bringing the country together. In contrast, the missionaries explicitly did not want to let the sins of the past be forgotten. In their view, salvation required confronting those sins directly — “without remembering there could be no repentance, and, therefore, no salvation.”89 So even when officials and missionaries shared a common goal, they often disagreed radically about the best means to achieve it.

One prefect, for example, urged the local archbishop to consider that “a public, animated discussion of several delicate and controversial issues will produce disquiet and reawaken disorder and hatred,” and suggested pointedly that they should avoid “any sort of spectacle which seeks to inflame the spirit of the people.”90 The police commissioner in La Rochelle wrote to the minister of the interior to sympathize with his town’s businesses and workers, who “are deprived of the means of their existence” because the mission had shut down carnival.91 Church officials tended to dismiss these arguments, responding like one archbishop that “far from destroying order and public tranquility, [religion] has always contributed to the maintenance of both.”92

One of the most common friction points was not whether a mission would occur at all, but how prominent it would be. Missionaries, for example, naturally sought to hold ceremonies in the evening, when as many people as possible could attend. But public officials saw nighttime services as most prone to riots and troublemakers, and they pressured — almost always unsuccessfully — the missionaries to wrap up their ceremonies before sunset. Officials sometimes, as we’ve seen, pushed back on plans to hold missions during Carnival. They often tried to censor missionaries’ sermons to avoid inflammatory content, and sent police spies to the missions to gather information about what the priests actually said. Prefects also applied pressure on missionaries to hold ceremonies indoors, rather than outdoor processions that would thrust them into view of — and potential conflict with — local nonbelievers.

This back-and-forth between the missionaries and public officials wasn’t uniform everywhere. Some prefects strenuously resisted the missions, while others enthusiastically backed them, and many in between promoted the missions but sought to rein in perceived excesses.93

The struggle continues

It would be a mistake, I think to focus too much on either side of the missions here. The backlash to the missions was real and important, but so were their successes in partially revitalizing French Catholicism. This struggle between the Church and its critics did not begin in the Bourbon Restoration, and it will still be being waged long after the last French Bourbons are dead.

But this long-term war is about to heat up in our narrative. During the first decade of the Restoration, the fierce local conflicts over Catholicism and the missions never rose to become a dominant national issue. That seems partly due to Louis’s reputation. Though he was a supporter of the missions, his image as a moderate and somewhat skeptical man who had clashed repeatedly with the Ultraroyalists took some of the force out of missionary controversies.

But in 1824 Louis died, and was replaced on the throne by his brother Charles X — who had a very different reputation. And as we’ll see in coming episodes, the religious controversies that simmered under Louis will erupt under his brother. Meanwhile, Charles will abandon some of his brother’s caution and much more openly align secular authorities behind the idea of a Christian monarchy as preached by the missionaries.94

I’ll explore all that in our next episode, which — I promise — will be out much more quickly than this one.

My thanks again to Bry Jensen of Pontifacts for the cold open. If this episode has you eager to learn more about the Catholic Church, and if you don’t mind a little light blasphemy between friends, be sure to check out Pontifacts! I’ve included a link at thesiecle.com/episode27. I’d also like to thank Steven Kurtz and David Perry for helping me track down copies of a few hard-to-find sources.

If you want to dive deeper, you should also be sure to check out Sheryl Kroen’s book Politics and Theater: The Crisis of Legitimacy in Restoration France, which is the work to understand the Tartufferie phenomenon, and also a fascinating look at the broader implications of religion and politics in the Restoration.

For now, be sure to tune in next time for Episode 28: Charles in Charge.

-

The audience for the parade included “some 20,000 visitors [who] poured into the city to witness it” in addition to “Clermont’s own population.” Maria Nicole Riasanovsky, “The Trumpets of Jericho: Domestic Missions and Religious Revival in France, 1814-1830,” 2 vols., PhD diss. (Princeton University, 2001), 255. Clermont-Ferrand had around 30,000 residents in 1818. Wikipedia, s.v. “Clermont-Ferrand,” last modified September 20, 2021. ↩

-

This entire anecdote is sources from Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 255-8. ↩

-

The porters were so eager for their jobs, in fact, that many of them refused to hand off the cross to the next group when their time was up, but cried “Encore! Encore!” and carried their burden further. Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 256. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 317. The nuncio in question was Vincenzo Macchi, the papal representative in Paris from 1819 to 1826. ↩

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 360-1. ↩

-

Peter McPhee, A Social History of France: 1789-1914. 2nd ed. (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 155. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 96-7. ↩

-

Sheryl Kroen, Politics and Theater: The Crisis of Legitimacy in Restoration France, 1815-1830 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 84. Jardin & Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 361. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 106. ↩

-

Roger Price, Religious Renewal in France, 1789-1870: The Roman Catholic Church between Catastrophe and Triumph (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 183. Price notes that “High levels of demand for manufactured goods, as well as continuous production processes and numerous exemptions, clearly made the legislation difficult to enforce.”. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 247. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 62. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 106. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 111. There was an effort to return maintenance of birth, marriage and death records to the Church in the first year of the Restoration, but this policy was defeated in the Chamber of Peers. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 19. ↩

-

Darrin M. McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 32-3. ↩

-

McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment, 99. ↩

-

Martyn Lyons, “Fires of Expiation: Book-Burnings and Catholic Missions in Restoration France,” French History, vol. 10, no. 2 (June 1996): 240–266, 251. ↩

-

McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment, 161. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 324-5. ↩

-

Mike Duncan, Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution (New York: Public Affairs, 2021), 190-1. ↩

-

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 11 May 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives. The quote has been cleaned up from the original, both to modernize punctuation and capitalization, and also to account for a cypher that originally concealed some incendiary parts of the original letter. The original is as follows: “102 in 12 are under intolerable 80 — altho’ oppen persecution does not now Exist, yet it depends upon the whim of 25; 28, 29, or any of 32 — marriages are not legal among them — their wills Have no force By law — their children are to Be Bastards — their parsons to Be Hanged.” In this cypher, “102” means “Protestants,” “12” means “France,” “80” means “Despotism,” “25” means “king,” “28” means “queen,” “29” means “parliament” (presumably the parlements), and “32” means “the ministers.”. ↩

-

McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment, 168. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 325. ↩

-

Aurelian Craiutu, Liberalism Under Siege: The political Thought of the French Doctrinaires. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2003. 32-35. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 106. ↩

-

Anka Muhlstein, Baron James: The Rise of the French Rothschilds (New York: Vintage Books, 1983), 41-45. ↩

-

Thomas Kselman, Conscience and Conversion: Religious Liberty in Post-Revolutionary France (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), 85. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 145. ↩

-

Thomas Kselman, Death and the Afterlife in Modern France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 71. ↩

-

Kselman, Death and the Afterlife in Modern France, 82-8. ↩

-

Kselman, Death and the Afterlife in Modern France, 86-8. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 92-3, 204. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 104. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 92-4. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 326. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 243. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 74. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 144-5. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 221. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 216. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 244. ↩

-

Carol Harrison, Romantic Catholics: France’s Postrevolutionary Generation in Search of a Modern Faith (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2014), 12. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 244-5. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 74, 106, 194. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 367. ↩

-

Wikisource contributors, “French Constitutional Charter of 1814,” Wikisource (accessed September 27, 2021). ↩

-

Even more than the Concordat’s compromises, the pope disliked the “Organic Articles,” a unilateral addendum to the Concordat that Napoleon had added after the treaty was signed. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 302. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 367-8. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 303-5. ↩

-

Geoffrey Cubitt, The Jesuit Myth: Conspiracy Theory and Politics in Nineteenth-Century France (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 24, 34-5. ↩

-

Cubitt, The Jesuit Myth, 66. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 367. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 295. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 111. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 302, 307-8, 318. Mansel, Louis XVIII, 208. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 84-6. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 405-10. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 87. Riasanovsky gives a somewhat different, and smaller figure, but the difference may be that Riasanovsky is only counting so-called “grandes missions” — 131 such affairs by the Missionaires de France and 65 by the Jesuits — while Kroen, citing Ernest Sevrin, does not appear to limit herself to just the biggest ceremonies. Riasanovsky, Jericho, 80-3. ↩

-

Lyons, “Fires of Expiation,” 244. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 241, 251, 277-88. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 101. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 240-1. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 209-10, see note. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 78-9. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 147-8. Our sources note that when the women were finally allowed in the next day, they brought food with them and picnicked inside the church, littering the floor with “chestnut shells and sausage skins”. Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 161. ↩

-

Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 211. ↩

-

Fernand Boulard, Materiaux pour l’histoire reliqieuse du peuple francais XXXe-XXe siècles, vol. 2. Riasanovsky, “Trumpets of Jericho,” 206. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 154. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 134. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 144. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 176-8. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 189. ↩

-

Lyons, “Fires of Expiation,” 249-50. ↩

-

Kselman, Death and the Afterlife in Modern France, 65-7. Bourreau was sentenced to six months in jail despite claiming at this trial that he was too drunk to know what he was saying. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 213. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 1-2. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 78. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 230. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 229-240. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 237. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 102. ↩

-

McPhee, A Social History of France, 98. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 96-104. ↩

-

McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment, 173-84. ↩

-

See Kroen, Politics and Theater, 23-36 and 105-110. ↩

-

Lyons, “Fires of Expiation,” 246-7, 249-50. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 91. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 209-10. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 99-100. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 100-1. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 210. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 125. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 144-9. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 119-20. ↩