Episode 5: The White Terror

Michel Ney was the most wanted man in France. Which makes it so odd that as the noose closed in on him in the fall of 1815, the man Napoleon dubbed “the bravest of the brave” seemed in no hurry to save his own neck — or to do much of anything, for that matter. Despite being given passports out of the country and a head start, the Marshal of France spent a month as a fugitive wandering around the rugged Massif Central, until finally police caught up with him and dragged him back to Paris a prisoner.1

Four months later, Marshal Michel Ney was executed by a firing squad. The charge was treason, against which Ney allegedly protested with his final words: “I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her.” That was true enough. But the last battle Ney fought in was Waterloo, commanding Napoleon’s left wing. Now Napoleon was on his way to permanent exile in St. Helena. Louis XVIII was monarch of France. And Michel Ney was merely the most famous victim of a sweeping purge that convulsed France in the fall of 1815, as Louis and his supporters tried to reassert control over a divided country.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, “La Mort du Maréchal Ney” (1868), Public domain via Wikimedia.

This is The Siècle, Episode 5: The White Terror.

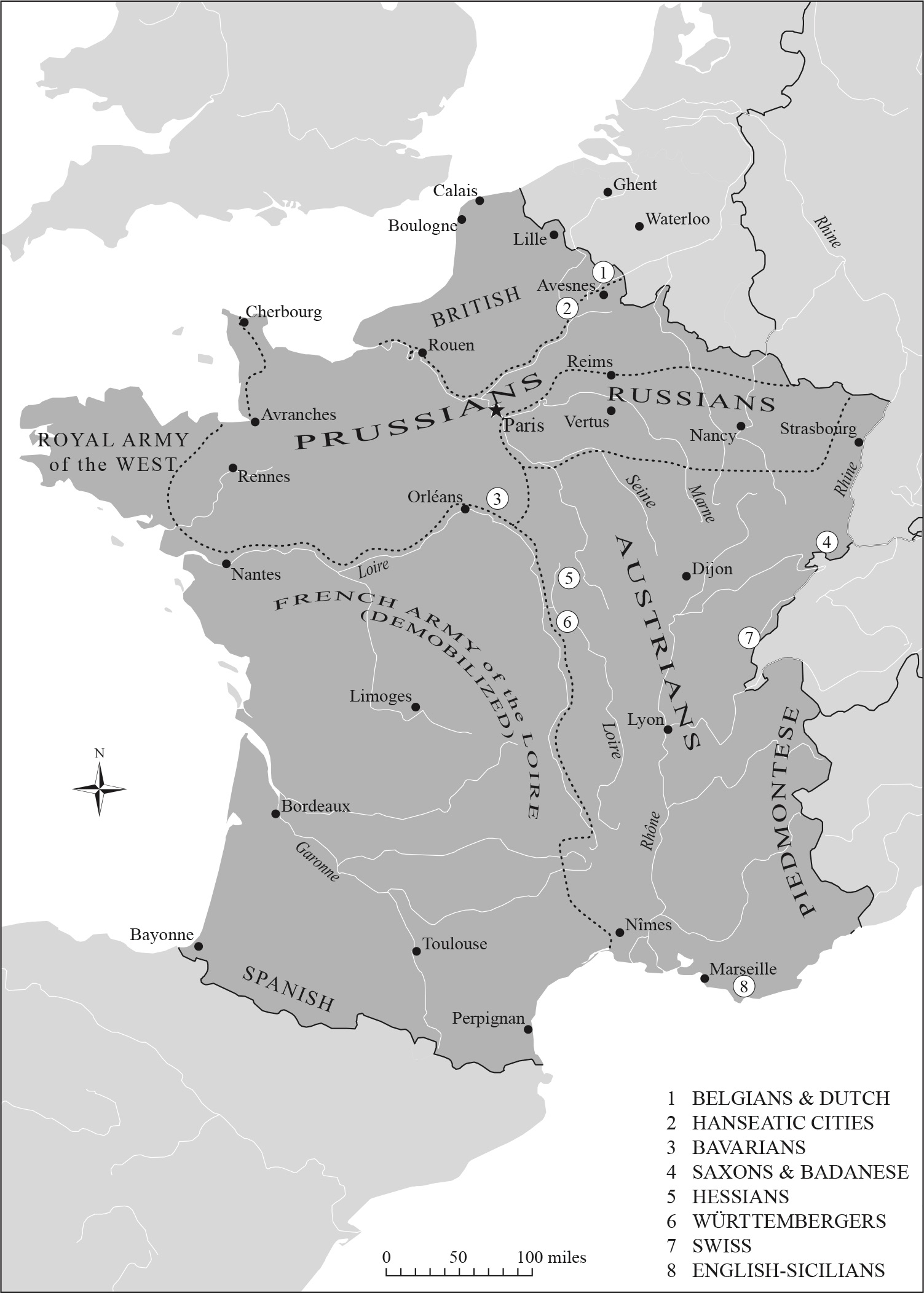

In the weeks after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in the summer of 1815, Allied armies poured into France from all sides, propping up Louis XVIII of the House of Bourbon as the restored king of France. In this respect, the Second Restoration was very similar to the First Restoration the year before, which I talked about in Episode 1: The Return of the King. But in other respects, 1815 was a much darker and more violent restoration — a rather unpleasant time to be in France, all told.

Occupation

For one thing, France was under a hostile occupation. Even when Napoleon was on his way to his final exile on Saint Helena as a British prisoner and Louis XVIII back on his throne, the Allied armies of Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia didn’t go home. They stayed, more than one million men spread out all over France, commandeering houses, food, and money from unwilling French families.

In Paris, where around 200,000 soldiers converged on a city of just 700,000 residents, the trees along the Champs-Elysée and in nearby public forests of the Bois de Vincennes and the Bois de Boulogne were chopped down for firewood, and a Prussian general occupied the Hôtel de Ville, or city hall, refusing to leave until Paris paid a 100 million franc “contribution” to its occupiers. The head of the Prussian army, General Blücher, nearly blew up a Parisian bridge, the Pont d’Iéna, because it was named after a humiliating defeat Prussia had suffered at the hands of Napoleon a decade prior. Fortunately for the Parisians, not all the foreign leaders were so vindictive as the Prussians: the Russian Tsar Alexander managed to lower the Parisian indemnity down to a still-massive 10 million francs, while the Duke of Wellington arrived just in time to save the bridge — and possibly the king, for an indignant Louis threatened to sit on the imperiled bridge himself.2

On top of this actual damage, the Parisians were subjected to a ceaseless string of insults and humiliations. Some were mundane, such as Parisians being forced to host the occupying soldiers in their homes, or drunk British soldiers staggering down the streets singing “Louis Dix-Huit, Louis Dix-Huit, We have licked all your armies and sunk all your fleet.”3 (Dix-Huit is the French word for “18.”)

Other insults were more substantial, the most famous of which happened in September of 1815, when Allied soldiers marched into the Louvre and carted out wagon after wagon of priceless art. In fairness, this art had been originally stolen by the French armies of the Republic and Napoleon and was only being returned to its prior owners, but that didn’t mollify the proud Parisians, who considered Paris and the Louvre the perfect place for these treasures.

“What a loss for the arts!” one pamphlet lamented. “These pictures, these vases, these statues, these bas-reliefs provided a unique assembly of the talents of all ages and all civilized peoples. Neighboring nations could admire and study these immortal masterpieces easily and without effort since France by its fortunate position is placed almost at the center of Europe.”

Somehow the Allied powers weren’t convinced, and sent a stream of artists to pick out the objects to be repatriated, including the Italian sculptor Canova on behalf of the Pope, and the folklorist Jacob Grimm on behalf of the Elector of Hesse in Germany. Crowds heckled the soldiers carting out the art and there was considerable concern that things might turn violent. King Louis actually sent his guards to stop the removal of the four bronze horses of St. Mark that Napoleon had stolen from the cathedral in Venice (though the Venetians had stolen them from the Byzantines in the first place) and displayed on top of a triumphal arch in front of the Tuileries Palace. Sadly for Louis, the Austrians returned with a bigger force the next day and forcibly removed the famous statues.4

For all the Parisian indignation, it’s worth noting that the Allies hardly stripped the Louvre bare. Nearly half of the paintings the French had taken from Italy over the prior two decades, for example, are still in French museums.5

The Parisians, however, were the lucky ones. Out in the countryside, the occupation was far more brutal and violent than the blows to Parisian pride. As author Christine Haynes recounts in her history of the occupation, Our Friends the Enemies, in village after village, soldiers fanned out and “wreaked havoc”: they stole everything possible from French homes and businesses, from food and gold to wine and weapons. Fields and villages were burned to the ground. Government treasuries were plundered and officials who protested were threatened and sometimes even arrested. Some French people were summarily executed.6

The occupation of France in 1815

Christine Haynes, “Military occupation, July-November 1815,” adapted from Roger André, L’occupation de la France par les Alliés en 1815: juillet-novembre (Paris: Boccard, 1924), 56-57. Map © Christine Haynes, used with permission.

Murder and pillage

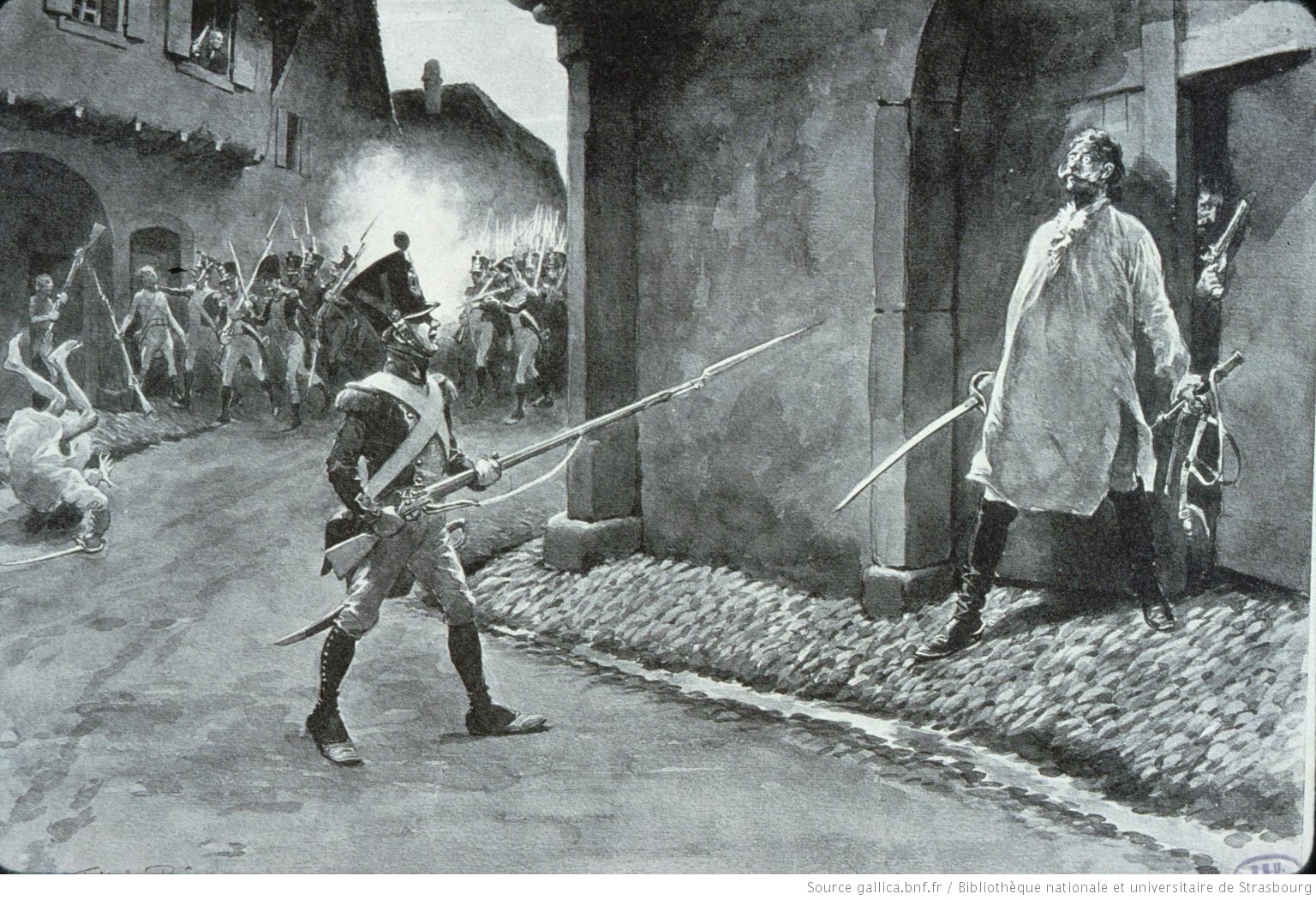

Neither wealth nor poverty spared the French from the cost of the occupation. Peasant farmers might be lucky to only have their crop seized, which threatened starvation. One report from a town in Champagne describes the inhabitants “being forced to cut [their] wheat before its maturity in order to feed themselves and the Allied troops with which they are crushed,” but a village a mile away was “entirely burned” by Bavarian soldiers and its inhabitants massacred for attempting to resist.7 Even routine interactions were fraught; German-speaking Prussian soldiers were noted for becoming irate when they couldn’t make themselves understood to the French, and would lash out with rifle butts or by throwing drinks in people’s faces. People who were forced to put Prussians up in their homes were often beaten by their unwanted houseguests. In many cases, peasants simply abandoned their homes and fled into the woods or hills to try to get away.8

A scene depicting street-fighting in the town of Mittelhausbergen in Alsace. Frédéric Regamey, “Surprise de Mittelhausbergen, 9 juillet 1815” (1905), public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The rich, meanwhile, were targeted for theft and extortion. In the Orne department in western France, one chateau was sacked for more than 20,000 francs in damages, with soldiers carrying off “not just silver, jewels and linen but books, engravings and objets d’art.” Not content with merely stealing, the Allied soldiers smashed mirrors and musical instruments that they couldn’t take away. In another mansion, the soldiers “left the lady who is living there with nothing but the dress and blouse she had on.”9

Even as their homes were being ransacked, notable citizens and officials were put upon to support the extravagant tastes of Allied officers, such as a two-week visit by Blücher to the city of Alençon that cost more than 18,000 francs just for his dinners, or a small-town mayor who hosted two lavish banquets for his local occupying garrison in an attempt to win leniency.10

Artist unknown, after Ernst Gebauer, “Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher,” public domain via Wikimedia.

The worst violence, as everywhere, was committed by the Prussians, who had suffered deeply under Napoleon’s invasions and were convinced the French deserved what they got. When French inhabitants complained about the plundering, Blücher responded: “They did only that? They could have done much worse.” The British soldiers were better behaved, but no more sympathetic. “We have conquered France,” wrote British diplomat George Canning, a future prime minister. “We want to exhaust her so that she will no longer budge for ten years.”11

All this was being done by the nominal allies of Louis, whose government struggled, largely impotently, to control the violence and pillaging. The remnants of the French army were disbanded, having proven they could not be relied upon by supporting Napoleon’s abortive return to power. But that left the French government with little leverage other than the goodwill of the occupiers, which could be in painfully short supply. While a formal treaty was hammered out, a temporary Commission on Requisitions was set up to try to formally manage the Allied demands for supplies, but the Commission received hundreds of complaints about Allied commanders ignoring this process and simply taking what they wanted. The Austrian forces, though less violent than the Prussians, were noted for being particularly greedy, seizing everything from taxes to tobacco from government warehouses. From June through November, Allied soldiers drank a reported 300 million bottles of French wine. All in all, historians estimate the occupation cost France a minimum of 2.5 million francs per day.12 As Louis protested fruitlessly to the other powers of Europe, gossip in the Parisian salons predicted the king’s second go on the throne wouldn’t last six months.13

Purge

Unfortunately for the French, foreigners weren’t the only thing they had to fear in the aftermath of Waterloo. Louis’s government and his supporters had their own scores to settle that put anyone even suspected of having backed Napoleon in a very tight spot.

This was in contrast to how Louis had handled things the year before, when he first returned to the throne. In 1814, as I described in Episode 1: The Return of the King, Louis tried not to rock the boat. He freed political prisoners, and welcomed former Napoleonic officials into his government. In fact, Louis had largely left the Napoleonic public service intact, from small-town mayors all the way up to many high state officials. After Napoleon’s re-seizure of power, even the more moderate of Louis’s supporters tended — with some justification — to see this leniency as a mistake that had enabled towns and army units to go over to their former emperor. So Louis began his second stint on the throne in 1815 with a purge.

Among the luckier victims were those who simply lost their jobs. Prefects, mayors and civil servants who had served Napoleon during the Hundred Days were unceremoniously sacked by the thousands. In general, people who had served the Empire before 1814 were fine — so long as they hadn’t sworn loyalty to Napoleon during the Hundred Days. But some who continued serving Napoleon were accepted if they were seen as sufficiently loyal or useful. And the chaotic system of purges, run by ad hoc committees, roving emissaries and even secret societies of ultra-royalists, had no general rhyme or reason. They were strict in some areas, lenient in others.14 Some victims might have been caught up in local or personal grudges.

Illustrating the chaos of this purge are examples of figures who straddled both sides of the fence during the chaotic period of summer 1815. A certain General Bourmont had defected to Napoleon, but had the good sense to defect back right before Waterloo.15 Instead of being fired or executed, he was promoted. Louis’s Minister of Police during this period, Joseph Fouché, had served the same role for Napoleon under the Hundred Days, but the wily Fouché had made sure to monitor which way the political winds were blowing and landed in the new government as well as the old.

All told, we don’t know an exact number of government employees who were fired, but historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny estimates a total between 50,000 and 80,000 men — that’s between one-fourth and one-third of all state employees.16

But as I’ve said, these people who were merely fired were in many ways the lucky ones. Louis’s government also brought criminal charges against thousands of Frenchmen for aiding Napoleon. Perhaps as many as 6,000 people faced political charges in the months and years after Waterloo. Unlike the most famous defendant, Ney, most of these people were poor and obscure, and were sentenced to prison, fines or hard labor instead of firing squads.17 People could be clapped in irons for such offenses as shouting “Long live the emperor,” passing on rumors that Napoleon had returned again, or wearing a carnation in your coat’s buttonhole — the carnation being one of several flowers that Bonapartists adopted as a symbol. In one absurd moment, a hen in northeastern France became a sensation for laying a flattened egg that vaguely resembled Napoleon. Police arrived to arrest the hen’s owner — and the hen.18 Under emergency laws passed after Waterloo, many of these political offenses could be tried in special courts with no juries and no appeals.19

Historian Robert Tombs judges the post-Waterloo repression as “substantial though not enormous by earlier or later standards” — which is small consolation to the people fired or imprisoned for their political beliefs, who would absolutely remember this crackdown and plot their revenge for whenever they themselves gained power again.20

Terror

Still, despotic and arbitrary though these special courts were, they were at least conducted through legal mechanisms. Perhaps the most notorious violence of this violent period was the actual “White Terror” that gives this episode its name — a spate of murders at the hands of vigilante ultra-royalist mobs.

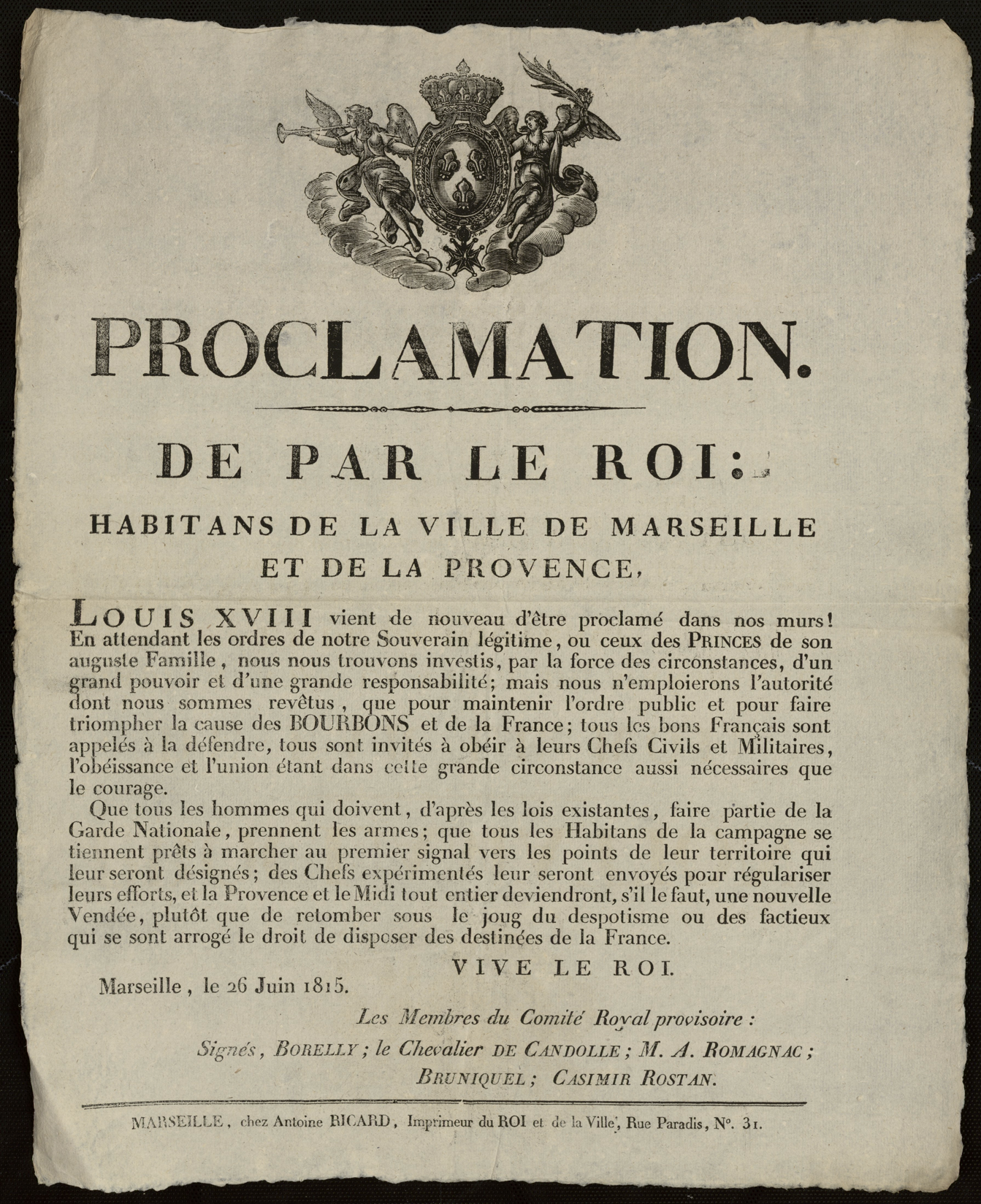

The murders began almost as soon as word of Napoleon’s defeat filtered down to areas where hard-core royalists were dominant. On June 24, just six days after Waterloo, royalist mobs formed in Marseille and went on a rampage against anyone with a tie, real or suspected, to Bonaparte. First they attacked the small imperial garrison, killing or wounding as many as 100 men before the soldiers withdrew. With the town now undefended, the so-called “tough boys” or nervis went after other Bonapartists, smashing up homes and shops and beating or killing those they got their hands on. As many as 50 people were killed in the rioting, including a number of Arabs who Napoleon had settled in Marseille after his expedition to Egypt.21

A proclamation printed on June 26, 1815, by “members of the Provisional Royal Committee,” addressed to residents of Marseille and the surrounding area. The proclamation asserts Louis XVIII’s return, calls on “all good Frenchmen” to defend Louis, and asserts a right to use this self-proclaimed power to both maintain public order and defend the Bourbons. Printed two days after the outbreak of mob violence by royalists against Bonapartists in the city, the proclamation commands Frenchmen to join the National Guard and obey orders — but ominously warns that if necessary to defend Louis as king, they are prepared to turn the south of France into “a new Vendée” — the royalist area in western France that famously resisted the Revolution for years. Public domain via Bibliothèque Méjanes (Aix-en-Provence).

The Marseille riots were only the beginning. As word spread of Napoleon’s defeat across the south of France, where royalists were in the majority, they seized the opportunity to take revenge on their enemies — sometimes spontaneously, and other times planned and organized by local elites. It’s known as the “White Terror” because white was the color of the Bourbons and ultra-royalism. Technically, in fact, this is the second “White Terror,” after an earlier uprising by conservative forces against the French Revolution in 1794-5. And that first White Terror itself followed the “Reign of Terror,” the famous spree of political murder led by Maximilien Robespierre and the left-wing Jacobins.

I mention this not to be pedantic about the name “White Terror,” which I’ll use to refer to these 1815 events, but because the history was important. Those prior spates of communal violence, perpetrated alternately by the left against the right and then by the right against the left, were still in living memory in 1815. Each outbreak of violence was sparked in part by a desire to get revenge for the last spate of violence on the part of the former victims, now that the political winds were blowing in their direction.

En Gard

Take, for example, the Gard department of southeastern France, located west of Marseille. In 1815, this was home to some of the most violent attacks of the entire White Terror. But this reflected decades-old grudges and centuries-old social and economic divisions, as well as the passions of the moment. The Gard was home to an unusually large community of Protestants, up to one-third of the population; the two sides had fought each other in France’s religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries before arriving at a very uneasy peace. By the time of the Revolution, this religious divide was overlaid on a socioeconomic divide: many Protestants had become merchants, bankers and manufacturers, living in towns and controlling a huge share of the region’s wealth, and when it came to hire workers they preferred their co-religionists. The area’s Catholic majority, in contrast, were primarily subsistence peasant farmers.21

In 1790, during the Revolution, a political struggle over departmental elections had broken into open violence. After provocations by armed groups of Catholics, the Protestants organized in force, with urban so-called “legions” being reinforced by thousands of Protestant peasants marching down from the hills. The result was a “frenzy of killing and devastation which left more than 300 Catholic royalists dead and many more wounded.” A few years later, when conservative forces were ascendant in the First White Terror, Catholic royalists formed “marauding bands” of brigands attacking their enemies, but this was suppressed, and through most of the Revolution and Napoleon’s empire, the Protestant minority was in economic, social and political control of the region. This divide had an ideological bent as well — Protestants tended to support both the Revolution and Napoleon, and the new social and economic order associated with those regimes, while Catholics were associated with traditional agriculture and royalism.22

None of the area’s wounds had healed by the time 1815 rolled around. The smooth transfer of power in the First Bourbon Restoration had seen an uneasy peace maintained, but police informants at the time noted that ultraroyalists were “occupying their time in preparing a report on everything that happened” in 1790. These long-nursed grudges exploded after Waterloo, when Catholic peasants were organized by ultraroyalist nobles into volunteer militias.

As in Marseille, the first targets were the garrisons of Bonapartist soldiers in town, of which perhaps 200 were massacred after surrendering — though those figures, as with others to follow in this particular account, might be exaggerated. Once the soldiers were out of the way, the violence expanded. On August 1, twelve Protestants were killed, most “shot on their own doorsteps.” Three days later nine Protestants were killed and 20 homes destroyed, while another royalist ringleader dragged six prisoners out of the town jail and executed them in the public square. On August 19, 15 Protestants were killed, five of them hacked to death with sabers. In almost every case, the royalists committed these murders wearing the uniforms of the National Guard.23

The attacks were, a police agent claimed, not random reprisals but chosen from “a list prepared in advance” by royalist ringleaders, many of whom were subsequently chosen for seats in the Chamber of Deputies in elections held in the middle of the killing. Unsurprisingly, not many Protestants voted.24

Altogether, anywhere between 50 and 300 Protestants were killed in the Gard. Thousands of other Protestants fled temporarily and hundreds were imprisoned, while 90 or more homes belonging to rich Protestants were destroyed.25 The attacks had accomplished multiple goals: revenge, ensuring political victory for the ultraroyalists, and also religious concerns: dozens of Protestants were forced to publicly convert to Catholicism.26 Even when Protestants weren’t killed, they were treated roughly: in one account, Protestant women supposedly had their underwear pulled off and were “beaten with a nail-studded paddle that marked their buttocks with a bloody fleur-de-lis.”27

Political assassinations

The White Terror in the Gard was the bloodiest and cruelest manifestation of the ultraroyalist revenge that flared across southern France in the summer and fall of 1815. But if other regions lacked the deep-seated social and religious divides that fueled the massacres in the Gard, they still saw their own spates of violence on a smaller and sometimes less deadly scale. Wearing green cockades, after the color of the king’s ultraroyalist brother the Comte d’Artois, the so-called “Verdets” fanned out to intimidate, pillage and arrest.28 Much as in the Gard, the White Terror elsewhere was fueled in part by vengeance for violence that revolutionaries or Bonapartists had themselves committed when they were in charge.

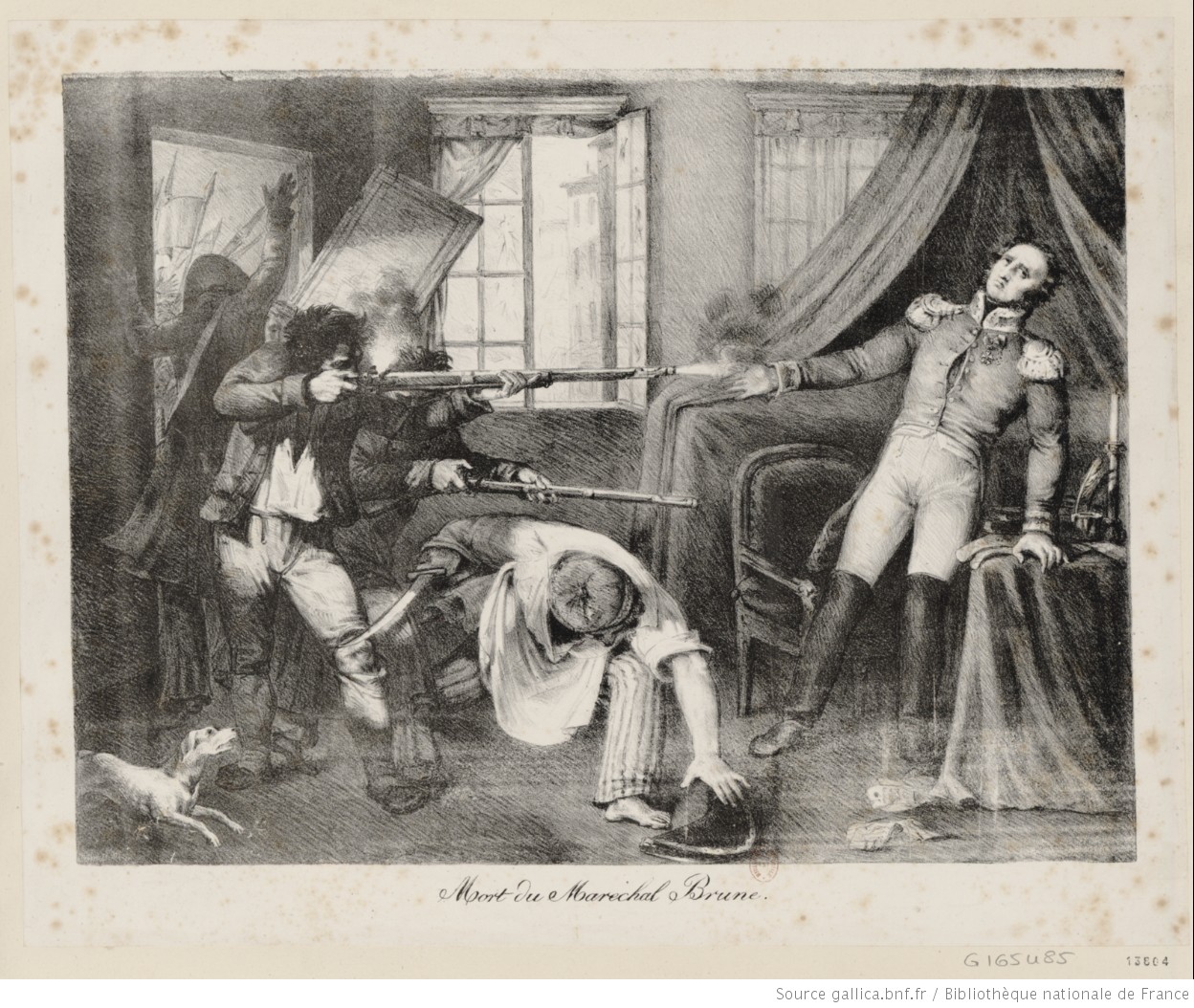

Outside of Marseille and the Gard, the most famous incidents of the White Terror involved the murders of prominent generals. A Bonapartist officer, Marshal Guillaume Brune, was passing through Avignon in southern France on his way back to Paris, when he was attacked by an angry mob and shot in the back of the head. His body was dragged through the streets and thrown into the Rhône river. In Toulouse, General Jean-Pierre Ramel fell victim to the Terror despite not being a Bonapartist at all — he was an agent of King Louis, sent to establish order in the region. But Ramel was assassinated by Verdets after he attempted to curtail them by enlisting them in the National Guard.29

Artist unknown, “Mort du Maréchal Brune,” public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The role of the government

So what was the relation between the the violence of the White Terror and the Parisian government of Louis — the king these royalists were ostensibly fighting to uphold? The king and his ministers certainly didn’t move with any great haste to quell the violence, which went on for several months. But this seems to be mostly due to surprise and confusion.

Some of this is perhaps justifiable — remember that the killing began even before Louis had re-settled on his throne, and after the fourth regime change in a little over a year, while the country was being invaded by more than a million foreign soldiers.

But even given the circumstances, Louis’s government responded chaotically. The southwest of France was the only area under the French government’s direct control, but who exactly was exercising this control? The king’s nephew, the duc d’Angoulême or Duke of Angoulême, had fled to Spain during the Hundred Days, and now assumed authority over southwestern France in the name of the king, appointing prefects from local conservative notables to govern the region’s departments. But the king’s prime minister in Paris, also in the name of the king, appointed his own set of prefects. This all took several weeks to sort out, meaning that, as de Sauvigny puts it, “for more than a month all the south found itself handed over to the arbitrary anarchical rule of royalist committees and gang leaders.”30 Western France, which was equally Catholic and royalist, saw comparatively little violence during this period. Both ordinary people and royalist leaders there were less eager to seize the opportunity to settle scores than their counterparts in the South.31

Not that the government was in a great position to end the violence, having effectively disbanded the remaining French army. This possibly necessary move proved ill-timed right when civil unrest erupted across large swathes of the kingdom.

Instead, the government was forced to rely on persuading ultraroyalist leaders to stand down. Its persuasive power rested with Angoulême, who was genuinely popular with the ultraroyalists, and who succeeded in initially calming passions. But even areas Angoulême thought he had pacified flared back up periodically, such as renewed violence in the Gard in November of 1815 when a Protestant church reopened. Embarrassingly for the French government, it took an occupation by Austrian soldiers to finally end the killing there.32

Louis and his ministers

I’ve been referring to “Louis’s government” and not “Louis” throughout this section because the king was exercising very little direct authority at this point. Though restored to his throne, Louis had withdrawn in these months from “active political life” and now left the day-to-day operations of government to his ministers.33

In part, this was because Louis had been obliged to appoint ministers he neither liked nor agreed with, in order to satisfy the Allied powers and elite public opinion. Thus a liberal ex-Napoleonic marshal, Gouvion Saint-Cyr, was Minister of War, while other liberals headed up the ministries of Justice, Finance and the Marine, or navy. Traditional royalists were entirely excluded.34

But the most prominent figures, and the most symbolic of this liberal ministry Louis was saddled with, were the Minister of Police, Joseph Fouché, and the foreign minister and de facto prime minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord — better known as Talleyrand.

Crime and Vice

Fouché we have already met, as a wily survivor who had served as Napoleon’s Minister of Police during the Hundred Days before betraying him and managing to keep his job under the Second Restoration. But this treachery was only the latest in a long and circuitous career for Fouché, a historical figure in the mold of George R.R. Martin’s fictional schemers Littlefinger and Varys. Fouché was a former revolutionary who had been too extreme in his methods of persecuting enemies of the Revolution even for Robespierre. He had then helped overthrow Robespierre and served in the revolutionary government that replaced him, the Directory, before in turn backing Napoleon’s coup that overthrew the Directory. But if Fouché was unprincipled, he was at least an effective Minister of Police, and that helped keep him around despite his one decision that incensed royalists and Louis more than any others: his vote, as a member of the revolutionary National Convention, to execute King Louis XVI.

Artist unknown, “Joseph Fouché, duc d’Otrante, ministre de la police”. Public domain via Wikimedia.

Talleyrand was less unprincipled than Fouché but scarcely less talented a political survivor. He, too, had served the Revolution, Napoleon and now the Bourbons, with foreign policy his field of expertise. When at his best, such as at the Congress of Vienna during the First Restoration, the club-footed former bishop was a brilliant diplomat. At his worst, he was completely untrustworthy and held views quite out of line with Louis’s relatively moderate conservatism. Louis had initially refused suggestions to appoint Talleyrand and Fouché to head his ministry, but he had been worn down by pressure.35

François Gérard, “Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754–1838), Prince de Bénévent” (1808). Public domain via Wikimedia

The author and statesman Chateaubriand observed Talleyrand and Fouché going in to finalize their appointments, recording the moment in a famous passage that I’m going to quote in full:

Suddenly a door opened: silently Vice entered leaning on the arm of Crime, M. de Talleyrand walking supported by M. Fouché; the infernal vision passed slowly before me, penetrated into the King’s room, and vanished. Fouché had come to swear fealty and homage to his lord; the trusty regicide, going down on his knees, laid the hands which caused Louis XVI’s head to fall between the hands of the royal martyr’s brother; the apostate bishop went surety for the oath.36

As minister of police, Fouché was put in charge of the crackdown on Louis’s enemies — the so-called “Legal White Terror.” He was the one who drew up the proscription lists of prominent people who were to be punished for their part in the Hundred Days. This was the list that Michel Ney was the first name on. And yet, even as Fouché was in charge of hunting down men like Ney, he was also quietly trying to help them escape. Fouché gave them warnings to get out of France, and passports to help them pass the border. Most people took advantage of this gift, with Ney and a handful of others getting caught by their own dithering or blunders.

This wasn’t necessarily another episode of treachery by Fouché. The restored regime wanted to punish its enemies, but it didn’t want to create martyrs — which Ney became, over the course of a sensational trial before France’s Chamber of Peers, or upper house of parliament. Louis is alleged to have said, upon hearing of Ney’s arrest, “He is doing us more harm by letting us catch him than he did when he betrayed us.” But Ney was the most famous, and infamous, of the figures to switch to Napoleon’s side during the Hundred Days, and it was “impossible to avoid punishing him.” He went before the firing squad on Dec. 7, in de Sauvigny’s words, “compensating for the errors of his life by the courageous grandeur of his end.”37

Marshal Ney was gone, but France’s troubles were far from over. In a few weeks, we’ll take a look at the political convulsions that wracked France in the year after Waterloo. But first, we’re going to delve a little bit deeper into the military occupation of France that I talked about in the first half of this episode. We’re going to do this with the first interview episode of The Siècle. In two weeks, you’ll be able to hear my conversation with Christine Haynes, a history professor at the University of North Carolina Charlotte, and the author of the recent book, Our Friends the Enemies: The Occupation of France after Napoleon.

In the meantime, be sure to visit the podcast’s website, thesiecle.com — that’s t-h-e-s-i-e-c-l-e. At thesiecle.com/episode5, with five as a numeral, you can read my full transcript of this episode, along with images and footnotes. If you enjoyed this episode as much as I did writing it, you’ll definitely want to check out the footnotes for observations and quotes that didn’t make it into the episode — including a coda to the story about the hen who was arrested for laying an egg that looked like Napoleon. Also on the website, you can see a special post I created, retelling the story of Napoleon’s Hundred Days in a new format: GIFs from the TV show The Simpsons.

My thanks for everything you do to support the podcast, including listening in increasing numbers, sharing it with your friends, and supporting it financially. Feel free to reach out to me with questions or comments on social media, where the podcast is @thesiecle on both Twitter and Facebook. And check back in two weeks for Episode 6: Our Friends the Enemies.

-

Dorothy Mackay Quynn, “Destination: America: Marshal Ney’s Attempt to Escape,” French Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (Autumn, 1961): 232-241. ↩

-

Christine Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies (Cambridge, Mass., and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2018), 21-2. Some accounts credit Louis’s threat with saving the Pont d’Iéna, but more recent historians such as Haynes are clear that it was other Allied commanders who forced Blücher to back down. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 259. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 93-95. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 96. ↩

-

Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies, 21, 24. ↩

-

Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies, 34. ↩

-

Alain Corbin, The Life of an Unknown: The Rediscovered World of a Clog Maker in Nineteenth-Century France, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 148. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 147. ↩

-

Corbin, The Life of an Unknown, 148. Corbin reports the cost of Blücher’s entertainment as “1,800 francs,” but Haynes cites the more believable figure of 18,000 and via personal correspondence confirmed that figure with other sources. ↩

-

Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies, 21, 26. ↩

-

Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies, 29-30. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 88. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 134-5. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914 (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 336. ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 135. ↩

-

Haynes, Our Friends the Enemies, 31-33. The figures about the number of people executed in the post-Waterloo crackdown can be confusing. Several thousand people were sentenced to death by special courts in this time, but only a handful of these were for political offenses. The bulk of those executed were charged with crimes like rioting or brigandage, not sedition ↩

-

Sudhir Hazareesingh, The Legend of Napoleon (London: Granta Books, 2004), 72-98. The novelist Stendhal concludes the tale in his diary: ‘The hen died in prison, but the memory of its egg remained.’ ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 131-2. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 337 ↩

-

Gwynn Lewis, “The White Terror of 1815 in the Department of the Gard: Counter-Revolution, Continuity and the Individual,” Past & Present, no. 58 (Feb. 1973), 110-1. ↩ ↩2

-

Lewis, “The White Terror… of the Gard,” 112-3. ↩

-

Lewis, “The White Terror… of the Gard,” 114-6. ↩

-

Lewis, “The White Terror… of the Gard,” 116, 127. ↩

-

Lewis, “The White Terror… of the Gard,” 116. Lewis cites around 100 Protestant civilians and around 200 soldiers; Sauvigny says “the number of 300 victims often quoted is too high” and that a more careful figure is probably “less than 100.” Sauvigny, Bourbon Restoration, 119. ↩

-

Lewis, “The White Terror… of the Gard,” 117-18. ↩

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 25. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914 (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 336. ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 118-9. Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 24-5. ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 118. ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 119. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 25. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 259. ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 116. ↩

-

Mansel, Louis XVIII, 255-6. ↩

-

François-René de Chateaubriand, Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb, translated by Robert Baldick (London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd, 1961. Reprint, London: Penguin Classics, 2014), 289. To clarify: “Vice” and “the apostate bishop” refer to Talleyrand, who had a club foot that impaired his walking, obliging him to lean on “Crime” — Fouché — the “trusty regicide” for his vote to kill Louis XVI. Royalists like Chateaubriand disdained both the high-born Talleyrand and the low-born Fouché, but for different reasons. ↩

-

Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 117, 133. Fouché’s initial list of proscribed names was so wide-ranging that Talleyrand famously quipped, “We must give [Fouché] credit for one thing, he did not forget any of his friends in drawing up the list.” The list was whittled down to 57 names as various Restoration figures lobbied to save their friends. ↩