Episode 28: Charles in Charge

This is The Siècle, Episode 28: Charles in Charge.

Welcome back. Our narrative left off a few episodes ago with a pivotal development for Restoration France: the death of King Louis XVIII on Sept. 16, 1824. That put Louis’s younger brother, the charming but conservative Comte d’Artois, on the throne as King Charles X of France.

Charles had been a heartbeat away from the throne for years. But even after finally attaining it, he had some formalities to attend to first. Ancient custom said new kings of France could not linger in the presence of their dead predecessors, so after a few moments Charles abruptly left Louis’s body for waiting carriages bound for the suburban palace of Saint-Cloud. The next day he received formal homage from the French royal family — his son and heir, the Duc d’Angloulême; the duke’s wife, the Duchesse d’Angoulême; his dead son’s widow the Duchesse de Berry and her children. Later in the day came the royal cousins, including the Duc d’Orléans. After the cousins came the politicians: the prime minister Joseph Villèle and the other ministers, who officially tendered their resignations; Charles refused them, and reappointed largely the same ministry under Villèle that his brother had had.1

A few days later came Louis’s funeral, in the suburban basilica of Saint-Denis. After the lavish event, we’re told Charles spoke briefly with the master of ceremonies to complement him on how well everything had gone. The man replied with an amusing faux-pas: “Oh, sire, your majesty is very kind, but there were many defects. Next time we will do better.” Charles apparently smiled and thanked the hapless M.C.: “Thank you… but I am in no hurry.”2

A few days later came Louis’s funeral, in the suburban basilica of Saint-Denis. After the lavish event, we’re told Charles spoke briefly with the master of ceremonies to complement him on how well everything had gone. The man replied with an amusing faux-pas: “Oh, sire, your majesty is very kind, but there were many defects. Next time we will do better.” Charles apparently smiled and thanked the hapless M.C.: “Thank you… but I am in no hurry.”2

Funeral carriage used for Louis XVIII. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

That kind of gracious charm is part of why Charles started his reign on the right foot, despite his very public immoderate politics. When he made a formal procession back into Paris on Sept. 27, he received an enthusiastic welcome from the gathered crowds. And why not? Whatever his politics, Charles was certainly much more fun in a parade than Louis had been. Paris had exchanged a reclusive, obese, invalid monarch for a charismatic silver fox. Where Louis had been carried around on a litter, Charles made his triumphal entry into Paris on the back of an elegant Arabian horse. Even his critics were forced to concede Charles’s charm, such as one enemy who begrudgingly wrote, “I have never seen anybody have so completely the attitude, forms, bearing and language of the court, so desirable in a prince.”3

And if Charles inspired admiration in his enemies, he received devotion from his allies; one gushed how even when Charles said something as banal as “good morning,” “his voice seemed to come so from the heart, he had such a gentle way of greeting, that it was impossible not to be moved by it.” And to be perfectly fair to Charles, this affection was not one-sided — after a brief fight with a retainer in which the aide had protested about his 34 years of service, Charles responded that it was better to say, “it will be 34 years that I have known and loved you.”4

But getting people to like him was never Charles’ problem. Remember back in Episode 26, when the Comte d’Artois entered Paris in 1814 to widespread acclaim? That didn’t last, as Artois became the public leader of the ultra-royalists. Will this same dynamic repeat itself as Charles tries to govern?

First steps

Charles started his reign off by doing all the right things. People were worried he sought to bring back the ancien régime, so he publicly swore to uphold the 1814 Charter. As a gesture of goodwill to the public, he granted a broad amnesty to people in jail for political crimes. And despite objections from Villèle, Charles abolished most of France’s remaining newspaper censorship. It worked: “for several days,” historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny writes, “it was all a cloudless idyl between Charles X and his people.”5

The new king also moved to smooth things over inside his family. In Episode 13 I discussed how Louis XVIII constantly snubbed his cousin Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans, whose offenses included a rather transparent desire to become king himself, as well as the fact that during the French Revolution Louis-Philippe’s father had voted in favor of executing King Louis XVI, who was Louis XVIII’s — and Charles’s — older brother. One of the ways Louis XVIII made sure Orléans was kept in his place was by denying him the court title of “Royal Highness,” the most distinguished rank available at court. This meant that when Orléans visited court with his wife — a Neapolitan princess who was a “royal highness” — both doors would be opened for the Duchesse d’Orléans, then one of the doors would be shut before the duke — a mere “Serene Highness” — was allowed to enter.6

The new king also moved to smooth things over inside his family. In Episode 13 I discussed how Louis XVIII constantly snubbed his cousin Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans, whose offenses included a rather transparent desire to become king himself, as well as the fact that during the French Revolution Louis-Philippe’s father had voted in favor of executing King Louis XVI, who was Louis XVIII’s — and Charles’s — older brother. One of the ways Louis XVIII made sure Orléans was kept in his place was by denying him the court title of “Royal Highness,” the most distinguished rank available at court. This meant that when Orléans visited court with his wife — a Neapolitan princess who was a “royal highness” — both doors would be opened for the Duchesse d’Orléans, then one of the doors would be shut before the duke — a mere “Serene Highness” — was allowed to enter.6

Above: Louis-Philippe d’Orléans and his wife, Marie-Amélie Thérèse de Bourbon. Lithograph by Antoine Maurin, circa 1830s. Public domain via the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Just four days after becoming king, Charles summoned Orléans to a private meeting where he granted the duke the coveted “royal highness” title. In this fascinating conversation — at least as it was related by Louis-Philippe — Charles effectively apologized for how his brother had treated Louis-Philippe. The king’s goal was to bind Orléans more closely to his regime, and to neutralize him as a dynastic threat. To that end, Charles appealed to Louis-Philippe’s self-interest in the royal succession, which ran through the young “miracle child” born after the Duc de Berry’s 1820 assassination. Charles told Orléans that “you must be aware of your position” — “between you and the throne there is only a four-year-old child, and at the least a four-year-old child is a very small thing… It is essential for us and even more so for you, that if he should die, you or your offspring should succeed without difficulties or embarrassments.” And in the immediate sense, this charm offensive worked! Even though Louis-Philippe had liberal inclinations and Charles was an ultra-royalist, the two generally got along well.7

The émigrés’ billion

But Charles wasn’t around just to make friends. He also wanted to use his power as king to accomplish things he thought France desperately needed — things his brother had been unwilling or unable to accomplish.

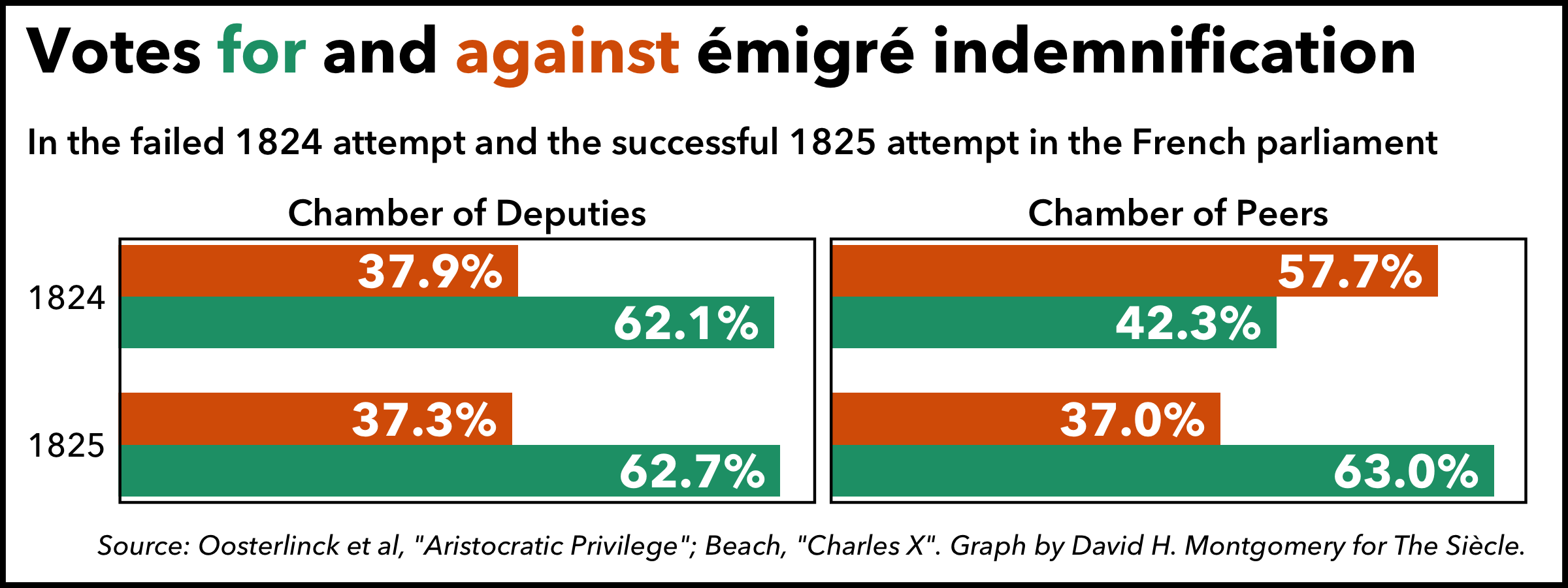

At the top of this list was a bill compensating French émigrés — the aristocrats who had fled the country during the Revolution — for land that had been seized from them and re-sold to the French people. These are the so-called biens nationeaux I’ve been talking about since Episode 1. Back in Episode 25, I discussed Louis XVIII’s attempt to resolve this issue: to compensate these émigrés with funds raised by refinancing France’s national debt. This failed in 1824, partially due to opposition to paying off a bunch of aristocrats, and partially due to owners of French bonds who didn’t want to hurt their investments.

At the top of this list was a bill compensating French émigrés — the aristocrats who had fled the country during the Revolution — for land that had been seized from them and re-sold to the French people. These are the so-called biens nationeaux I’ve been talking about since Episode 1. Back in Episode 25, I discussed Louis XVIII’s attempt to resolve this issue: to compensate these émigrés with funds raised by refinancing France’s national debt. This failed in 1824, partially due to opposition to paying off a bunch of aristocrats, and partially due to owners of French bonds who didn’t want to hurt their investments.

François Séraphin Delpech, after Jean Sébastien Rouillard, “Jean-Baptiste Guillaume Joseph, comte de Villèle,” c. 1815-1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One year later, Charles and Villèle were ready to try again. Rather than repeat the same failed plan from 1824, however, Villèle opted to divide and conquer: The bill compensating émigrés for their seized property was introduced separately from the bill to pay for it. Unlike the year before, this time there was to be no forced refinancing of existing government debt. Instead, most of the indemnity was funded the old fashioned way: by borrowing more money. The measure did include a refinancing provision, but this was optional — which meant that in practice, the only bondholders who voluntarily accepted lower interest rates on their investments were people who were coerced into it, such as people working government jobs.8

Getting this passed was not a casual effort. Not only did Villèle’s ministry push hard for the bill, but Charles put his personal prestige behind it, lobbying peers and deputies both privately and at public court receptions. When it ultimately passed after fierce debate, Charles considered it a personal triumph.9

Overall, around 70,000 people received some payments, with the average payment around 45,000 francs. But most recipients received far less than this, since that average was inflated by a few major landowners who got millions — most of all the Duc d’Orléans, who received nearly 13 million francs from the indemnity bill, more than anyone else.10 (Charles, interestingly, didn’t receive a single franc — the king’s property was counted as state property, and Charles explicitly rejected any special provision for him.11)

From a cold, dispassionate perspective, this indemnity bill — dubbed the “émigrés’ billion” from an estimate of the total cost in francs — can be seen as a success. The émigrés had been causing social unrest by agitating for the return of their lands; they were now paid off and quieted down. A prosperous France could afford the cost. Owners of the biens nationeaux, meanwhile, now had a big question mark about the future of their lands removed, and on average saw their land value go up. After 1825, there were “no longer two types of property” in France.12

But politics doesn’t function on a cold, dispassionate level. The “émigrés’ billion” was hugely controversial, with liberals condemning it as a giveaway to the traitorous elite, a betrayal of the Revolution. Meanwhile émigrés hadn’t been asking for an indemnity — they had wanted their lands back. And for many of them, the payments fell far short of what they thought they had lost. So from a political perspective, Charles and Villèle had riled up the opposition without fully satisfying their base.13

Holy orders

In the same legislative session where the Chambers were debating the “émigrés’ billion,” Charles’ government put forward bills on an even more controversial topic: religion.

As I’ve covered in Episode 27 among others, religion was an issue of huge importance in Restoration France, and it was particularly important to the devout Charles. Supporters of the Catholic Church wanted to restore some of the legal privileges the Church had lost in the Revolution, and Louis XVIII had only been willing to go so far. But in his first full legislative session in 1825, Charles made these religious measures a priority.

The less controversial of the two religious bills Charles backed in 1825 gave new rights to religious orders. The legal rights of these groups had been sharply restricted in France for decades, especially men’s orders, while women’s groups had been tolerated to various degrees but not given legal recognition. One limitation of this legal limbo: even tolerated or underground religious orders were banned from acquiring property.14

This limitation reflected a few factors, including general anti-clerical sentiments, as well as the gender divide in religiosity that I talked about in Episode 27 — religiously active women were seen as less of an issue than religiously active men. The issue of property that I mentioned was also a particular concern — many heirs objected to their dying parents leaving large bequests to the Church, and accused priests of pressuring people on their deathbed to save their souls by leaving their fortunes to God.15

In response to complaints from the Church, Louis’s government had proposed in 1824 to let new religious orders be authorized by government officials, rather than requiring a separate new law authorizing each new order. But this had been shot down in the Chamber of Peers. So in 1825 Villèle came back with a revised bill that only granted this recognition to women’s religious orders. Even this wasn’t enough, and the bill only passed after being watered down more, to the disgust of Charles and many ultra-royalists. Still, even this watered-down version had a huge impact, setting off a nationwide boom in new women’s religious orders.16

Sacrilege

But for all the debate this bill on religious orders prompted, it was small potatoes compared to the other religious bill introduced in 1825: the sacrilege law.

This measure was inspired by reports about repeated thefts of sacred communion vessels from churches — 538 such thefts in four years. Under the existing Napoleonic law, thefts from churches were actually punished less severely than thefts from homes, and many ultra-royalists wanted to change that.17 But the sacrilege bill was also tied up in the broader religious currents I discussed last episode, including a desire on the part of some ultra-royalists to reforge the links between throne and altar and to expiate the sins of the Revolution with acts of public devotion.18 Villèle himself does not appear to have been an enthusiastic supporter of the sacrilege bill, but felt he needed to shore up his right flank by giving the ultras something they wanted.19

In response to these demands came the sacrilege bill, which imposed draconian punishments for any thefts from churches. Steal anything from a church and you faced either a lifetime sentence of hard labor or solitary confinement. And that was the lenient part. For people who stole or profaned communion vessels or sacramental bread, the bill proposed a strikingly baroque death sentence. Not merely was the convict to be executed, but they were to first have their hand cut off — the traditional punishment for killing one’s father, applied in response to a sin against God the Father.20

For devoted Catholics, this made sense. Catholic doctrine teaches that communion, or the Eucharist, literally transubstantiates bread into the body of Christ. So any theft or defilement of the sacramental bread wasn’t just a symbolic blow, but a very real attack on God — worthy, supporters argued, of the most extreme punishment possible.

For devoted Catholics, this made sense. Catholic doctrine teaches that communion, or the Eucharist, literally transubstantiates bread into the body of Christ. So any theft or defilement of the sacramental bread wasn’t just a symbolic blow, but a very real attack on God — worthy, supporters argued, of the most extreme punishment possible.

The ultra-royalist deputy and writer Louis de Bonald defended the law: “As for him who commits the crime of sacrilege, what do you do by passing sentence except send him before his natural judge… before the one who alone can pardon those who have repented.”21

Above: Louis de Bonald by Julien Léopold Boilly, circa 1814-1840. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Critics were apoplectic. The liberal Duc de Broglie, whose wife was a Protestant, pointed out that Protestants and non-believers would see the law as a threat: “The freedom of religion relies on the great maxim that… the legislator will remain, not indifferent, but neutral,” Broglie said. “Violate this maxim just once, draw the sword just once in support of a purely theological truth, and then the principle of intolerance of consciences, the principle of persecution looms beside you.”22

Critics were apoplectic. The liberal Duc de Broglie, whose wife was a Protestant, pointed out that Protestants and non-believers would see the law as a threat: “The freedom of religion relies on the great maxim that… the legislator will remain, not indifferent, but neutral,” Broglie said. “Violate this maxim just once, draw the sword just once in support of a purely theological truth, and then the principle of intolerance of consciences, the principle of persecution looms beside you.”22

Victor de Broglie, Duc de Broglie, engraving by Antoine Maurin and Nicolas Eustache Maurin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And for anyone who was at all sympathetic to liberal ideas, it seemed positively medieval. The legislator Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard attacked the bill for introducing “a new principle of criminality, an order of crimes which is, so to speak, supernatural… As such the law throws into question both religion and civil society, their nature, their ends, and their respective independence.”23

Even some conservative Catholics recoiled from the law’s severity, such as Chateaubriand — author of the famed book The Genius of Christianity — who said, “The religion which I presented for the veneration of men is a religion of peace which likes to pardon rather than punish, which wins its victories by mercy, which only needs the scaffolds for the triumphs of its martyrs.”24

But as with the “émigrés’ billion,” Charles championed the bill and spent his political capital to get it passed. The most effective argument for securing wavering lawmakers may have been this, from the bill’s primary sponsor: “In order to succeed in having laws respected, we must begin by having religion respected.” That, combined with an amendment removing the dramatic hand-chopping bit from its punishment, helped it pass into law.25

The great irony is that after all this tumult, the fiercely divisive sacrilege bill was effectively never enforced. No one was ever executed under the law’s infamous provision for profaning the eucharist. One historian argued, with only a little exaggeration, that the law’s only victim “was the regime crazy enough to accept responsibility for it.”26

The road to Reims

These new bills passed in the spring of 1825 were still recent news in May, when Charles planned a grand spectacle to give his reign a formal beginning: a coronation ceremony.

Left: King Charles X in his coronation robes, by François Gérard, c. 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Attentive listeners of the show might be trying to remember the nature of Louis’s coronation, and coming up empty. That’s not a problem with your memory — Louis XVIII never had a coronation. To be sure, he intended to have one, and Article 74 of his charter had specified that a king was to be formally crowned. But initial plans were disrupted by Napoleon’s return for the Hundred Days. After that passed, they tried again — only for the Duc de Berry’s 1820 assassination to put an end to the second attempt. And once the dust had settled from all that, Louis’s physical infirmities made a grand ceremony impossible. Louis ruled for a full decade without ever having his reign formally consecrated in a traditional ceremony.27

So if Louis got on just fine without any formal coronation, why did Charles have one? There are two big reasons, which happen to neatly mirror the two key aspects of Charles’ character: the religious and the secular.

The religious reason for a ceremony had to do with a particular conception of kingship, one that privileged the king as “God’s physical, corporeal representative on Earth,”28 in contrast to a constitutional model of kingship where the king was a representative of the people. Charles didn’t embrace some of the more elaborate medieval coronation theology29 but it was important to him to have a religious ceremony where he could receive God’s blessing as France’s king.

The secular reason is the same reason why modern U.S. presidents hold fancy inaugurations with parades, speeches and balls — to rally support for their regime from both elites and masses with impressive and symbolic ceremonies. Charles wanted to convey that he was God’s choice as king of France, to be sure — but he also wanted to convey that France under him was rich, stable and powerful. So no expense was spared to put on a show.

Splendor

“The Coronation of Charles X,” by François Gérard, 1827. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

After months of planning, Charles’ coronation took place on May 29, 1825, in the cathedral of the city of Reims, about 80 miles or 129 kilometers northeast of Paris. (More on this city of Reims shortly!) The ceremony itself started at 7 a.m. and lasted more than five hours. It featured an array of foreign and domestic dignitaries, songs and blaring organs, trumpet fanfares and the release of a thousand doves.30 Charles entered the cathedral dressed in simple white, but after being anointed donned elaborate silk coronation robes with gold embroidery and abundant jewels and plumes — “man transformed into God before the audience’s eyes”.31 The cathedral itself was lavishly decorated inside and out, transformed from the stark Gothic style into something much more gaudy.32 (In fact, in a case of life imitating art, some of the decorations were literally props from the Paris Opera.33) Not everyone was a fan, of course — a young Victor Hugo, attending as the coronation’s official poet, thought all the cardboard to be cheesy, but the young champion of Romanticism found a bright side: “Six months ago,” Hugo told his wife, “they would have turned the old Frankish church into a Greek temple.”34

Those not elite enough to be inside the cathedral could participate in the celebrations, too. A crowd assembled outside the cathedral was treated to cannon salutes and the distribution of commemorative medals.35 Elsewhere, local festivals were staged around the country in honor of Charles’ coronation.36 In a typical example, the western city of Nantes featured a parade, outdoor games in city squares, a formal ball and fireworks.37

Those not elite enough to be inside the cathedral could participate in the celebrations, too. A crowd assembled outside the cathedral was treated to cannon salutes and the distribution of commemorative medals.35 Elsewhere, local festivals were staged around the country in honor of Charles’ coronation.36 In a typical example, the western city of Nantes featured a parade, outdoor games in city squares, a formal ball and fireworks.37

Above: Commemorative medals struck for Charles X’s coronation in 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

An operatic coronation

Residents of Paris got an extra bonus besides the usual festivities: an array of plays and operas inspired by the coronation. Some of these were literally attempts to let ordinary people experience the coronation, though Paris theaters were limited by censors who banned any actual depictions of King Charles on stage. (British theaters were under no such restriction, and Londoners could go see not one but two different recreations of the coronation on stage.) Mixed in with these patriotic celebrations of Charles were more comedic pieces, like one play called “Windows for Rent” that made fun of the prices some residents of Reims were able to charge visitors to view Charles’ procession through town.38

Residents of Paris got an extra bonus besides the usual festivities: an array of plays and operas inspired by the coronation. Some of these were literally attempts to let ordinary people experience the coronation, though Paris theaters were limited by censors who banned any actual depictions of King Charles on stage. (British theaters were under no such restriction, and Londoners could go see not one but two different recreations of the coronation on stage.) Mixed in with these patriotic celebrations of Charles were more comedic pieces, like one play called “Windows for Rent” that made fun of the prices some residents of Reims were able to charge visitors to view Charles’ procession through town.38

A 16th Century depiction of Pharamond, the mythical first king of the Franks. Unknown engraver, c. 1580. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The theatrical highlights, however, were two dueling grand operas. One of them was Pharamond, an immense and serious piece set in the distant, half-remembered past of pre-Roman Gaul. It was written by three teams of French composers and librettists, each pair writing one of the three acts. Pharamond drew explicit allegories between the mythical Frankish King Pharamond and the current French King Charles, and featured elaborate operatic costumes and set designs.39

The other big coronation opera was about as different as you could imagine. Instead of French composers writing an opera about French mythic history, it was written in Italian by the opera superstar Gioachino Rossini — famed for such works as The Barber of Seville. Il Viaggio a Reims — or “The Road to Reims” — was set in the literal present, May 1825, and was about a group of people traveling to Reims to attend Charles’ coronation. The libretto by Luigi Balocchi had just the barest gesture at a plot — the aristocratic travelers get stuck at an inn, and pass the time by flirting and singing with each other. Various antics intersperse with transparent propaganda, like the climactic scene where the aristocrats suggest topics for an improvised solo such as Joan of Arc or France’s sainted King Louis IX; when the winner is drawn “randomly,” it is — quelle surprise! — the glory of King Charles X.40

The other big coronation opera was about as different as you could imagine. Instead of French composers writing an opera about French mythic history, it was written in Italian by the opera superstar Gioachino Rossini — famed for such works as The Barber of Seville. Il Viaggio a Reims — or “The Road to Reims” — was set in the literal present, May 1825, and was about a group of people traveling to Reims to attend Charles’ coronation. The libretto by Luigi Balocchi had just the barest gesture at a plot — the aristocratic travelers get stuck at an inn, and pass the time by flirting and singing with each other. Various antics intersperse with transparent propaganda, like the climactic scene where the aristocrats suggest topics for an improvised solo such as Joan of Arc or France’s sainted King Louis IX; when the winner is drawn “randomly,” it is — quelle surprise! — the glory of King Charles X.40

Gioachino Rossini, by Constance Mayer, 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ultimately, however, most of these coronation-inspired theatrical spectacles had short shelf lives despite initial popular interest. At the time Pharamond had the longest run of the shows in question, even enjoying some revivals in the next few years — though it’s now largely forgotten. Viaggio is better known today, but at the time it was pulled after just a few performances at Rossini’s insistence, despite sell-out crowds.41 That was because Rossini intended to cannibalize his best music from it for a later opera about a more durable topic.42 The Viaggio score was soon lost, and only reconstructed in the 1970s.43

More enduring than all this spectacle would be the political overtones of Charles’ coronation. Every detail was planned to try to send messages about what kind of king Charles wanted to be — though the French didn’t always go along with Charles’ preferred messages.

Modernity and tradition

The overriding issue as Charles and his aides planned the coronation was a tension between tradition and modernity. To what degree should Charles reach back to the centuries-old traditions of the ancien régime monarchy, and to what degree should he forge something new?

The overriding issue as Charles and his aides planned the coronation was a tension between tradition and modernity. To what degree should Charles reach back to the centuries-old traditions of the ancien régime monarchy, and to what degree should he forge something new?

French coronation chalice used in the anointing of Charles X. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

For example, where should the coronation take place? Dating back a thousand years, French kings had been crowned not in Paris but in the Reims cathedral.44 (The city of “Reims” might sound confusing to you, but that’s because Reims is one of the weirder bits of French pronunciation out there. It’s spelled R-e-i-m-s, and as an American I had always pronounced it “Rhymes” until I learned better.)

But not everyone thought emphasizing a connection to the medieval monarchy was appropriate for a post-Revolution France. They pointed to a recent counter-example: when Napoleon crowned himself emperor, he did so not in Reims but at Notre-Dame, right in the heart of Paris. Other people argued that the entire concept of a religious coronation ceremony was an anachronism unworthy of the modern age.45

On this matter, as I noted earlier, Charles and the committee he appointed to work out the details sided with tradition. The coronation would take place in Reims.

The King’s Evil

Another holdover from the past was a peculiar ceremony that took place the day after the coronation: a ritual called “touching for scrofula.”

“Scrofula” is an old name for a disfiguring but not usually fatal disease caused by the tuberculosis bacteria. It involves swollen lymph nodes and sometimes skin lesions. The face of a scrofula sufferer, we’re told, becomes “putrid” and gives forth a terrible odor.46

But more than its medical symptoms, by far the most interesting thing about scrofula is that starting in the Middle Ages, there was a widespread belief in England and France that the way to cure it was the touch of a king — giving it the common name, “the King’s Evil.” For example, in 1535, the theologian Michael Servetus wrote that:

Two memorable things are related of the kings of France: first, that there is in the church at [Reims] a vase of [consecrated oil] which remains ever full, sent down from heaven for the coronation, and used for the anointing of all the kings; secondly, that the king, by the laying on of hands alone, cures the scrofula. I have seen with my own eyes this king touching several sufferers from this affection. If they were really restored to health — well, that is something I did not see.47

King Henri IV of France touches the head of a kneeling man for scrofula, circa 1589-1610. Unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

We’ll come back to that consecrated oil in a moment. For now let’s stick with the scrofula. How did this very particular ailment get associated with a royal touch as its cure? Part of it was a belief that kings weren’t just political leaders but were in some sense divinely blessed — “that the sovereign’s power was supernatural, and that both his authority and his person were sacred.”48 And scrofula in particular was a disease well-suited to such a supernatural cure — even setting aside the placebo effect, scrofula’s symptoms frequently come and go on their own. As such, it’s relatively easy to imagine how a natural remission might look like a miraculous cure.49

Medieval and early modern kings didn’t only touch for scrofula as part of their coronations, but it was closely associated with being crowned.50 The tradition faded in England by the early 18th Century, but continued in France right up until the Revolution. King Louis XVI touched 1,200 sufferers at his 1774 coronation, and at least some produced certificates of having been cured.51

Fifty-one years later, Louis’s brother Charles had his own coronation, and sufferers of scrofula showed up for their touch purely driven by tradition — there was no announcement that the ritual would take place. Indeed, we’re told Charles vacillated over whether to touch for scrofula or not, and he may have initially ordered the assembled sufferers to disperse before changing his mind. Regardless, he finally showed up and duly walked through lines of around 120 people with scrofula, making the sign of the cross on their foreheads and reciting the ritual words: “God cure you, the king touches you.”52

It was the very last time that any European monarch would ever carry out the medieval ritual of touching for scrofula.53

Concessions to modernity

All this so far may give you an impression that whatever debates were had, Charles came down thoroughly on the side of tradition for his coronation. That’s probably true — and it’s definitely the impression that his liberal critics took away at the time. But it is important to note that Charles’ coronation did make several prominent concessions to modernity.

The traditional coronation oath was modified to include a promise to “govern in conformity with the laws of the kingdom and the constitutional charter.” Charles also omitted the traditional phrase promising “to exterminate in the territories under his jurisdiction heretics named and condemned by the Church” and invited representatives from Protestant, Jewish, Orthodox and Muslim communities to attend. The crown, sword, and royal scepters were carried not by nobles of ancient bloodlines but by four marshals of France — men who had fought their battles under Napoleon and the Revolution, “an era of French history which Charles X was eager to forget.”54

“Because you have had yourself anointed, you will be massacred”

There were two symbolic components of Charles’ coronation, however, that would loom large in the public consciousness.

One was either the most miraculous or the most ludicrous part of the whole affair, depending on your perspective. One of the other traditions of French coronations, as mentioned above, was the use of a container of sacred oil to anoint the new king, oil that legend said had been delivered by a dove from heaven for the coronation of the first Christian French king, Clovis, way back in the 5th Century. Unfortunately, this vial had been smashed during the French Revolution. But days before Charles’ ceremony, the Archbishop of Reims announced that loyal servants of king and Church had in fact secretly saved a few drops of the sacred oil from destruction, enabling Charles to be properly anointed after all.55 For the devout, this was a divine miracle, a sign of God’s favor. For the skeptical, this was hokum, a transparent and convenient lie meant to win over the gullible.

The second resonant event related to how that miraculously recovered oil was used. During the anointing ceremony, Charles prostrated himself face down before the altar and the bishops. For its defenders, this was a totally normal part of the traditional religious coronation ceremony, a display of proper humility before the majesty of God, and not even worthy of note.56 But for people worried about the role of the Catholic Church in French life, who were concerned by the recent Sacrilege Law, and by the ongoing revival missions, the idea of the king prostrating himself before the clergy would prove to be a damning and enduring symbol. A popular song written after the coronation portrayed “Charles the Simple” kneeling at the feet of “prelates stitched in gold” and swearing an oath not on behalf of France but of the pope in Rome.57 A Parisian bridge was graffitied with the ominous threat: “Because you have had yourself anointed, you will be massacred.”58

Above: The consecration of King Charles X during his coronation ceremony, by François Gérard, 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Charle’s reentry into Paris after his coronation, by Louis-François Lejeune, June 6, 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. The exuberant welcome depicted here is contradicted by sources saying Charles received a muted reception.

We shouldn’t read too much into this, though. The first year of Charles’ reign had fired up his critics, but when the king returned to Paris after his coronation he was met not with jeers but with relative silence. The ultra-royalist priest Félicité de Lamennais — a fierce advocate for a blasphemy law a few months earlier59 — wrote, “The entry of the king was, whatever the newspapers say, very sad and gloomy — no screaming, no love, just a silent curiosity for the spectacle, that’s all.”60 Charles wasn’t widely hated, and he wasn’t doomed, but his honeymoon phase was clearly over. A coronation intended to rally the nation around him had not done its job. Now he’d have forge forward with his agenda against an emboldened opposition who had more power than he liked to admit.

We shouldn’t read too much into this, though. The first year of Charles’ reign had fired up his critics, but when the king returned to Paris after his coronation he was met not with jeers but with relative silence. The ultra-royalist priest Félicité de Lamennais — a fierce advocate for a blasphemy law a few months earlier59 — wrote, “The entry of the king was, whatever the newspapers say, very sad and gloomy — no screaming, no love, just a silent curiosity for the spectacle, that’s all.”60 Charles wasn’t widely hated, and he wasn’t doomed, but his honeymoon phase was clearly over. A coronation intended to rally the nation around him had not done its job. Now he’d have forge forward with his agenda against an emboldened opposition who had more power than he liked to admit.

We’ll pick up Charles’ story soon. But first we’ve got to flesh out some of the fun details I’ve laid out today and in recent episodes. I’ve got a few great bonus episodes lined up with academics and podcasters, delving deeper into things like the weird French court institution of “Monsieur” and the very weird history of scrofula.

Once those are done, it’s time for a long-overdue introduction to some of Charles’s most potent political opponents. Join me next time for Episode 29: The Doctrinaires.

-

Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 179-80. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 365. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 365. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 368. As mentioned in Episode 22, the censorship regime imposed after the assassination of the Duc de Berry had effectively ended in 1822. But the replacement bill, which ended most censorship but toughened up libel laws, had a clause allowing the king to re-impose censorship in “grave circumstances.” On Villèle’s recommendation, Louis had done just that in 1824, despite the absence of any particular emergency. This was the censorship regime that Charles abolished upon taking the throne. Irene Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 1814-1881 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), 37, 47. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 219. ↩

-

Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 115-6. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 184-7. Kim Oosterlinck, Loredana Ureche-Rangau and Jacques-Marie Vaslin, “Aristocratic Privilege: Exploiting ‘Good’ Institutions” (discussion paper, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London, October 22, 2019), 14. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 372-3. The 45,000 franc estimate is the face value of the bonds that émigrés received, or an average annual payment of around 1,377 francs. The real value of the bonds ended up being somewhat less than 45,000 francs. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 373. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 373. Beach, Charles X, 184-6. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 312. ↩

-

Thomas Kselman, Death and the Afterlife in Modern France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 99. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 374-5, 312-3. ↩

-

Mary S. Hartman, “The Sacrilege Law of 1825 in France: A Study in Anticlericalism and Mythmaking,” The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Mar. 1972), 24. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 375. ↩

-

Hartman, “The Sacrilege Law of 1825 in France,” 26. ↩

-

Sheryl Kroen, Politics and Theater: The Crisis of Legitimacy in Restoration France, 1815-1830 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 113. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 376. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 113. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 376. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 376. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 114. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 198. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 377-8. Kroen, Politics and Theater, 118. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 24. ↩

-

Such as where an effigy of the dead king would be kept on display to receive visitors and be served meals, as if the old king had never died until the moment his successor was crowned, Kroen, Politics and Theater, 25. Indeed, Kroen notes that Charles’ true antecedents weren’t so much the medieval kings as France’s 17th Century Bourbon monarchs — in contrast to their Enlightenment 18th Century successors who moved away from many traditional divine trappings of monarchy. Kroen, Politics and Theater, 118. ↩

-

Many of these doves promptly died, burned by the lighted chandeliers. The ultra newspaper Le Drapeau blanc tried to turn the event into a political allegory of, as historian Benjamin Walton summarized, “the sad results of too much liberty given to a people too fast.” Benjamin Walton, “‘Quelque peu théâtral’: The Operatic Coronation of Charles X,” 19th-Century Music, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Summer 2002), 18n72. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 11. Beach, Charles X, 201-2. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 378-9. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 3-5. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 7-8. ↩

-

Graham Robb, Victor Hugo: A Biography (New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 119. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 118. ↩

-

Denise Z. Davidson, France After Revolution: Urban Life, Gender and the New Social Order (Cambridge, Mass., and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2007), 58-9. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 6-7, 9. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 6-7. Pharamond was inspired by the nationalistic epic poem La Gaule poétique by Louis-Antoine-François Marchangy. Marchangy is the poet-prosecutor who we first met convicting the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle, and who Victor Hugo later mocked as a “counterfeit Chateaubriand.” Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 16. ↩

-

Janet Johnson, “A Lost Masterpiece Recovered,” liner notes for Rossini: Il Viaggio a Reims, Gioacchino Rossini et al (Hamburg: Deutsche Grammophon, 1985), 36-40. Janet Johnson, “Synopsis,” liner notes for Rossini: Il Viaggio a Reims, Gioacchino Rossini et al (Hamburg: Deutsche Grammophon, 1985), 40-42. ↩

-

Viaggio was Rossini’s last opera in Italian, and marked his début on the Paris stage after the superstar composer was recruited to move there by the French government. His recruitment began in the final months of Louis XVIII’s reign, and was finalized by Charles X — though the change of kings led to Viaggio being Rossini’s debut work in Paris instead of his original plan. Richard Osborne, Rossini (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 92-94. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 21. ↩

-

Johnson, “A Lost Masterpiece Recovered,” 36-40. ↩

-

Marc Bloch, The Royal Touch: Sacred Monarchy and Scrofula in England and France, translated by J.E. Anderson (Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2020), 12. ↩

-

Bloch, The Royal Touch, 186. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 24. ↩

-

Bloch, The Royal Touch, 242. ↩

-

James F. Turrell, “The Ritual of Royal Healing in Early Modern England: Scrofula, Liturgy, and Politics,” Anglican and Episcopal History, vol. 68, No. 1 (March 1999), 6. ↩

-

Peter McPhee, A Social History of France: 1789-1914. 2nd ed. (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 111. Bloch, The Royal Touch, 225-6. ↩

-

Bloch, The Royal Touch, 227. Beach, Charles X, 205. ↩

-

Bloch, The Royal Touch, 227. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 378-9. Beach, Charles X, 202. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 379. ↩

-

Kroen, Politics and Theater, 169-70. Kroen notes that this translation “doesn’t capture either the rhyme or the insult in threatening the king with the familiar tu.” That original: “En t’ait fait sacré, tu sera massacré.”. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 375. ↩

-

Walton, “The Operatic Coronation of Charles X”, 20. ↩