Episode 37: Algiers

This is The Siècle, Episode 37: Algiers.

Welcome back. Last time, we took a doomed voyage on the frigate Medusa to explore France’s relationship with its West African colony of Senegal. Today, we’re going to stay in Africa but go a little closer to French shores: the Ottoman Regency of Algiers in North Africa.

This autonomous state had a cosmopolitan population and a complex relationship to France involving trade, war, money and piracy. A complicated web of all these factors are going to come together to make the Regency of Algiers play a pivotal role in the reign of King Charles X of France. So in order to know what Charles is getting into, today we’re going to dive into the background of Ottoman Algeria with the help of an expert guide: Professor Ashley Sanders, a historian who is the Vice Chair of Digital Humanities at UCLA.

Sanders has researched Ottoman Algieria extensively, and joined me from a research trip to France to talk about this fascinating land on the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

The Siècle is part of the Evergreen Podcasts network. Visit evergreenpodcasts.com for more great shows. You can also visit thesiecle.com/episode37 for a full transcript of this episode, with links, maps and images. My thanks to Heather Hughson for transcribing this episode.

My thanks also to the show’s latest supporters on Patreon: Todd Anderson and Alec. They and all other patrons receive an ad-free fees of the show. Visit thesiecle.com/support to join for as little as $1 per month.

Now, here’s my interview with Ashley Sanders.

THE SIÈCLE: Professor Sanders, welcome to the Siècle.

THE SIÈCLE: Professor Sanders, welcome to the Siècle.

ASHLEY SANDERS: Thank you for the invitation, I’m happy to be here.

SIÈCLE: Could you introduce yourself to the audience, you and your research interests, how you got interested in Algeria?

SANDERS: Sure. I am a comparative colonial historian by training, but I also picked up an interest in digital humanities along the way, and I’ll explain how the two connect as we talk. I was really struck in a class I took in graduate school with French attempts to colonize Algiers [contrasted] with similar attempts in North America. I was really intrigued by some of the parallels I saw, and eventually that project kind of changed and evolved over time, but my interest in Algeria remained.

And through research in the archives for my dissertation project, I stumbled across a memoir from the last Ottoman governor of Constantine, Algeria. It was absolutely fascinating, so that’s what’s driven my current research, focusing specifically on the Ottoman government in Algeria and its society, and the roles of the governors themselves as well as their family members, including women, and Jewish actors in North Africa.

Above: Professor Ashley Sanders, Vice Chair of the Digital Humanities Program at UCLA. Submitted photo.

SIÈCLE: Let’s get started with just a high-level summary of what Algeria looked like at the moment where our narrative is right now, which is early 1830. What was Algeria at this time, who was in control, and what was life like there?

SANDERS: In 1830, Algeria was part of the Ottoman Empire, it was its westernmost province, and so you have an interesting milieu at this time. It was quite cosmopolitan, there were European ambassadors there, there were Europeans in charge of French fishing concessions, as well as British fishing concessions. They had agencies that managed the rights and the fisheries as well as trade through those agencies. There were sub-Saharan Africans there, unfortunately mostly as slaves.

There were also Berbers who lived primarily up in the mountains. These are the indigenous inhabitants of North Africa, and speak a different language. There were also Arab descendants in Algeria from previous invasions from the 8th Century. So, you get this really interesting mix of people. And then of course you have the Ottomans, some of whom were Turks by ethnic background, and others were from European states, and had been drafted into the Janissary corps or the elite military corps of the Ottoman Empire. And so, they were the ones in charge of governing Algeria, the Ottomans were. So they policed the region, they collected taxes, but that was really about the extent of their government.

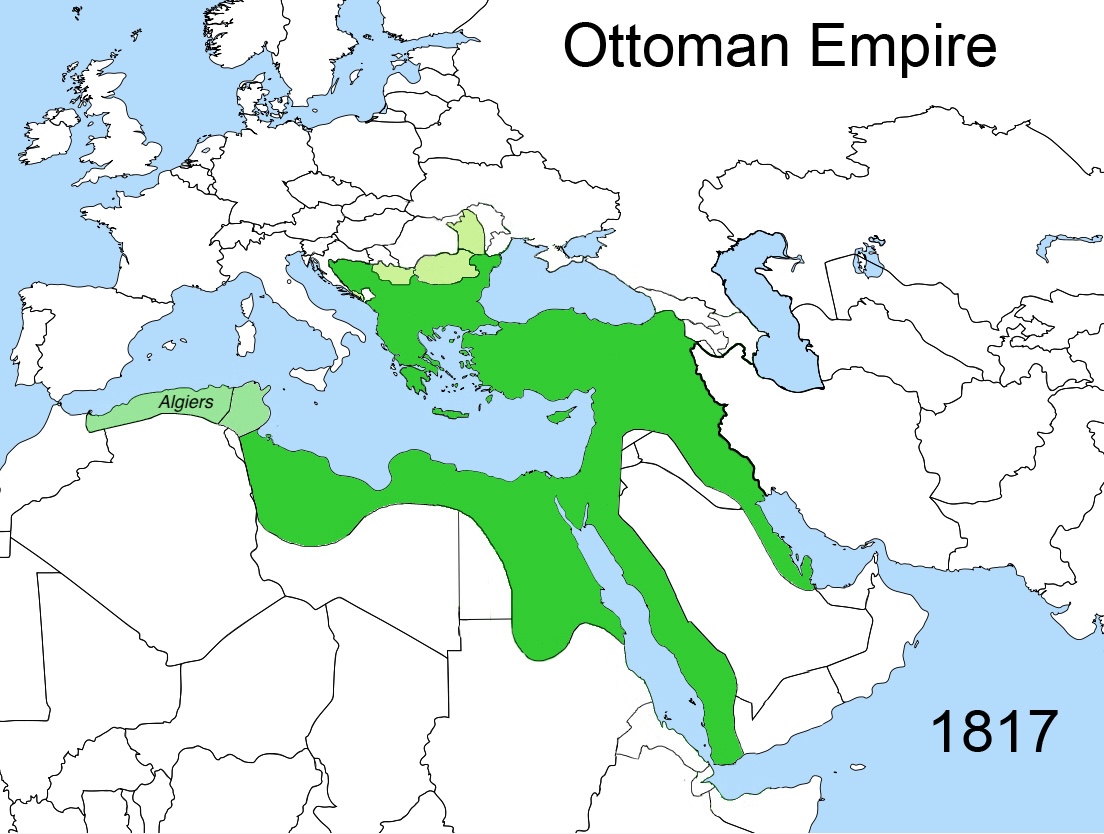

Approximate borders of the Ottoman Empire circa 1817. The Regency of Algiers is the westernmost territory along the south coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Note that different parts of the empire had varying degrees of functional autonomy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

SIÈCLE: Listeners of the Siècle are familiar with the status of Egypt in this time, which was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, but functionally independent in a lot of ways, Certainly self-governing in many ways, with interesting and complicated relationships with Constantinople. How independent was Ottoman Algeria compared to other parts of the Empire, and how much control with the Sultan back in Constantinople have over what happened in Algeria?

SANDERS: That’s a great question, because the Sultan did not have as much control certainly as he wanted, and I think Egypt is a really good comparison with Algiers. Because just as Egypt was fairly autonomous, fairly independent, so was Algeria, which frustrated the Sultan to no end because — as we’ll talk about throughout our conversation — the corsairs who had letters of marque, meaning that they were pirates who had been given license to be pirates, specifically for a state — acted of their own accord. And this caused many legal headaches and challenges for the Ottoman Empire because Algeria acted in its own interest, and also often negotiated on its own behalf with European powers rather than going through the Ottoman state. So, even though the Ottoman Empire sent administrators, military officials to Algeria, it was sort of a dashed line of authority between the Ottoman Empire in its seat in Istanbul and Algeria.

SIÈCLE: One final bit of introduction here, and we’ve used a couple terms already that may be confusing to some people who are not familiar with the history and geography of Algeria, we’ve used terms like Algeria, Algiers, Constantine. Can you just give a quick overview of what some of the key places that we’re talking about are, and how they were referred to at the time versus how people might know them today?

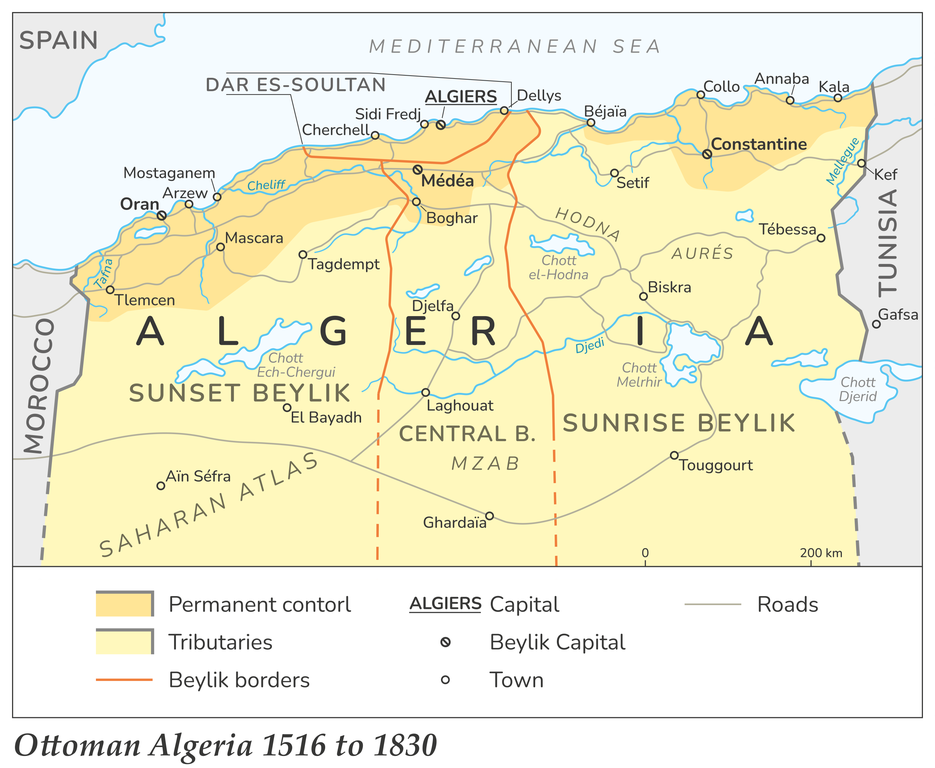

SANDERS: Definitely. So, Algeria was comprised of three different provinces during the Ottoman period. There was the western province of Oran, which had various capitals, and you can look this up because they changed over time, especially because of Spain’s involvement in that region — they held cities for hundreds of years, there were constant battles between Algeria and Spain over those territories. Then you have the central territory, where the seat of government was and is, and that’s Algiers, the capital of Algeria. And then you have the eastern province of Constantine, and its capital city is a city by the same name. And these names at least – Oran, Algiers, and Constantine — have remained constant.

SIÈCLE: No pun intended.

SANDERS: Yeah.

[both laugh]

Map showing the direct and indirect territory of Ottoman Algeria, including the major administrative centers of Oran, Algiers, Constantine. By Wikimedia user Cattette, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license via Wikimedia Commons.

SIÈCLE: So we already talked about a few things – the interaction of Spain here, the corsairs, this shifting relation to the Ottoman Empire. Let’s go back a little bit in time, and talk about the recent history of Algeria before the early 19th Century. How did Algiers and Algeria get to the place that it was in early 1830?

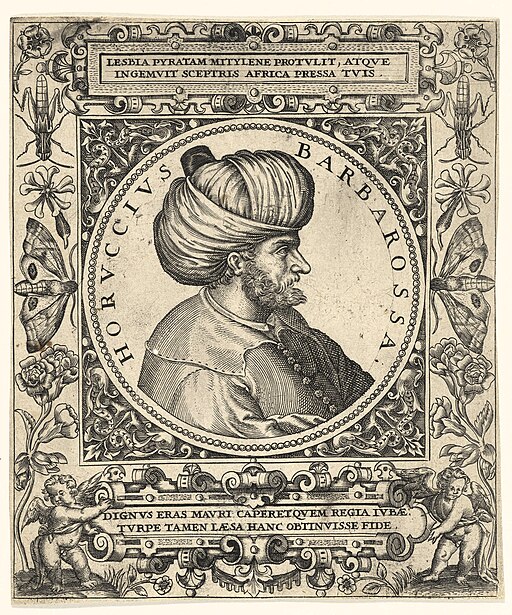

SANDERS: So, Algeria became part of the Ottoman Empire when a couple of enterprising brothers, the Barbarossas, who were pirates, decided that they wanted a land base, and decided Algeria would be a pretty good place for that, right along the Mediterranean, it has a long Mediterranean coastline and harbors that are protected and would protect and provide a kind of safe, literally a safe harbor for the pirates. So they made an agreement with the Algerians that they would help them oust the Spanish, who had conquered many of these cities along the coastline, but the Barbarossas got out of their depth, they invited the Ottoman Sultan to send some troops to help out, and in return, Algeria would then pay taxes to the Ottoman Empire and become a province within the larger imperial government.

SANDERS: So, Algeria became part of the Ottoman Empire when a couple of enterprising brothers, the Barbarossas, who were pirates, decided that they wanted a land base, and decided Algeria would be a pretty good place for that, right along the Mediterranean, it has a long Mediterranean coastline and harbors that are protected and would protect and provide a kind of safe, literally a safe harbor for the pirates. So they made an agreement with the Algerians that they would help them oust the Spanish, who had conquered many of these cities along the coastline, but the Barbarossas got out of their depth, they invited the Ottoman Sultan to send some troops to help out, and in return, Algeria would then pay taxes to the Ottoman Empire and become a province within the larger imperial government.

Above: 16th Century depiction of the corsair Oruç Reis, also known as Baba Oruç or Oruç Barbarossa, who with his brother captured Algiers for the Ottoman Empire. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This happens between 1516 and 1518, and by 1518-1519, around the same time that Egypt was also incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, so was Algeria. So then, as we move forward, the Ottoman Sultan honored this agreement, he sent governors and he sent janissary soldiers to help protect and maintain this new province, and to help collect taxes, and send them back to the Ottoman state. But as we kind of pass through time between 1518 and around 1780, there is an evolution of Algeria’s wealth and its relationships with European powers. And over this time, Algeria had to rely quite a bit on piracy and corsairing for its economic stability. They were also involved in trade, but they had to turn to piracy because the European powers were pretty effective all the way back in the 15th Century at shoving Algeria out of that trade, and so they had to kind of muscle their way back in, and one way to do that was to engage in corsairing.

But by the time we reach the late 18th Century, corsairing was on the decline. The European powers were getting much better at addling pirates on the high seas. And Algeria went through a number of years of plague, which took a huge toll on their population, as did famine and invasion of pests, particularly locusts that devoured their crops. And the environment and the soil in Algeria is very sensitive to these kinds of changes. It’s a very delicate ecosystem, and with the invasion of pests, anything like that, it can take out the entire crop for the season.

And so, with these plagues, with the pests, and with the famines, if we take Algiers as just one example of the effect of the combination of these three factors, the population in Algiers in 1780 was over 100,000 people. By 1830, it had dropped to 30,000 people. So many people had died of this kind of triple tragedy, and so Algeria was really struggling by 1830 in a lot of ways.

SIÈCLE: Just to be clear, you’re talking about the city of Algiers here, not the province of Algiers.

SANDERS: Correct. But these tragedies affected people throughout Algeria, not just the capital. In Constantine for example, in 1805, there were riots because there was a wheat shortage, and people were literally starving. And so we can see these effects kind of ripple across the entire region.

SIÈCLE: You mentioned that delicate climate in Algiers and Algeria more broadly. I think a lot of people’s impression of North Africa is just desert, but especially the northern coastal area was very different from some of those impressions. Can you talk a little about what the geography was of Ottoman Algeria?

SANDERS: To talk about the geography of Algiers, it might be helpful to provide a quick picture of visitors’s impressions upon first arriving in the capital of Algiers, and sailing into this port before we talk about the terrain and the other regions around the capital. So, sailing toward the short, the city of Algiers rises gracefully from the port and the coastline, up the mountainside. And one newcomer’s description is representative of many other people’s first impressions: “The houses rise gradually from the seashore, up the ascent, in the form of an amphitheater. The town appears beautiful at a distance when approaching from the water. The mosques, castles, and other public buildings have a striking effect.”

SANDERS: To talk about the geography of Algiers, it might be helpful to provide a quick picture of visitors’s impressions upon first arriving in the capital of Algiers, and sailing into this port before we talk about the terrain and the other regions around the capital. So, sailing toward the short, the city of Algiers rises gracefully from the port and the coastline, up the mountainside. And one newcomer’s description is representative of many other people’s first impressions: “The houses rise gradually from the seashore, up the ascent, in the form of an amphitheater. The town appears beautiful at a distance when approaching from the water. The mosques, castles, and other public buildings have a striking effect.”

Above: Pictorial map of Algiers from the perspective of a sea approach, circa 1690, by Gerard van Keulen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

So, as you approach from the sea, you can see the houses which were all painted in white rising up the hillside, and so Algiers has been described as resembling the head of a veiled woman, or as a ship’s topsail spread out on a green field, it was really a beautiful, stunning first sight of this city as you approach it.

And then, when you depart from the boat, you’re struck by this hive of activity. You have biskris, who are people from the oases from the desert areas of Algiers, who are primarily responsible for carrying heavy loads of goods from the ships into the city for distribution. You also see sub-Saharan Africans who often worked as slaves, also helping to carry goods from place to place. You see Europeans disembarking from boats, going to businesses, or as part of consuls, retinues, as well as Berbers from the mountainsides, Arabs, and Ottomans as well. So this is a really dynamic, active city, as you first enter it.

SIÈCLE: I imagine there were also fairly visible defenses as well.

SANDERS: Yes, so I’m glad you mention this, because this is something else I wanted to bring up. Algiers, because it was home for many corsairing activities, also needed quite vast defense structures. So there was a big almost like wall, that kind of came out and wrapped around the harbor to provide defense. There were cannons set along that wall, and because of the topography of that city, with the hillside rising right up from the sea, along the top, the ramparts at the very top of the city, there were also more cannons that protected that harbor. And so, the defenses often also struck visitors.

I have another quote from the American consul, William Shaler, who arrived in 1816, and he wrote: “All the approaches by sea to Algiers are defended by such formidable works, mounted with heavy cannon, as to render any direct attack by ships a desperate undertaking if they were defended with ordinary skill and spirit.”

Along the coast, and for about a hundred to two hundred kilometers inland, it’s a quite fertile region. You’ve got several mountain ranges that go through there, and mountain ranges are also quite fertile, especially on the side that received more rain, and so there were a number of crops that were grown in Algeria. Olives were grown, figs, wheat and other grains were staples. Before you get to those desert areas that we often think of when we think of North Africa, you had many farms. You had — particularly — the Berbers were more sedentary, and had family farms, particularly in the mountains. You also have a number of tribes, you had large herds of sheep and goats that ranged through this quite fertile region.

As I mentioned, it was very delicate and very sensitive to the sometimes harsh weather. It could be quite extreme and also be sensitive to these invasions of pests.

A modern-day satellite map of northern Algeria, with tinted relief, showing greenery along the northern coast, and desert further inland. Personal work, including imagery ©2023 TerraMetrics and map data ©2023 Instituto Geográfico Nacional and Google, via Google Maps. Terrain relief, borders and city locations via Natural Earth.

SIÈCLE: In the last episode of the Siècle, we talked a lot about the issue of slavery, particularly in the Senegal region. In that episode, I mentioned that aside from the famous transatlantic slave trade, there was also the trans-Saharan slave trade, and you mentioned that many of the sub-Saharan Africans in Algeria at the time were slaves. Can you talk about the role of slavery in Ottoman Algerian society — slavery and slave trading — and what kind of impact that had both domestically and internationally?

SANDERS: The slave trade that I’m most familiar with in Algeria was that practiced by the pirates and the corsairs. So again, the corsairs had license to practice piracy, they were licensed by the state. Pirates were those without licenses. Both operated from Algeria, and they often attacked particularly European ships traveling through the Mediterranean, and not only would they capture the cargo, but they would capture the people as well.

Some would actually serve as slaves in Algeria, they would be taken back to the port and sold at market. The governor of Algiers would usually have first choice of any of the slaves that were brought in to become a part of his household, and then the others were sold at auction.

Slave market in Algiers, by Jan Luyken, 1684. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

However, there is also an enormous system that connected Algeria to European cities throughout the Mediterranean region, and to a number of lending houses as well, because there was a system of redemption, where families could gather up money or they could work with lenders to pull together a collection of money to buy back their loved one who had been captured and brought to Algeria. So there was an enormous network of people involved in this process of redeeming captive slaves.

SIÈCLE: You talked about how in the late 18th Century, a series of interlinked disasters started to really buffet Algeria. What was the situation in the first decades of the 19th Century? Obviously there is a lot going on in Europe at this time, it’s the years of the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars — talk a little bit about what was happening in these first early decades of the 19th Century.

SANDERS: During this time, as you mentioned, the Napoleonic Wars were happening. During that time, Algeria was providing wheat to some of the European powers, particularly to France to feed the troops. But then as we just talked about, this series of disasters that affected the harvest in Algeria made it impossible for them to export, and so Europe turned to other countries to provide for the needs of the troops, and also just for regular imports for the population.

SANDERS: During this time, as you mentioned, the Napoleonic Wars were happening. During that time, Algeria was providing wheat to some of the European powers, particularly to France to feed the troops. But then as we just talked about, this series of disasters that affected the harvest in Algeria made it impossible for them to export, and so Europe turned to other countries to provide for the needs of the troops, and also just for regular imports for the population.

Right: “The Bombardment of Algiers, 27 August, 1816,” by George Chambers Sr., 1836. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In Algeria itself, we see a decline in corsairing, particularly after the Bombardment of Algiers in 1816. This was a collaboration between Great Britain and the Netherlands to get Algeria to release the Christian captives, or the captives from European countries, because there were still over 1,500 European slaves in Algiers at this time. Together, Great Britain and the Netherlands bombarded the city of Algiers, that had already been decimated by, as I mentioned, these disasters, and they pummeled the city for two days, until the governor finally came to terms with the commander of the fleet and signed a truce releasing the European captives — but also declaring that Algerians would not participate in corsairing or piracy in the Mediterranean any more.

SIÈCLE: I imagine that must have been quite a disruption to the Ottoman economy, as well as the Ottoman prestige in Algeria.

SANDERS: Very much so. So, this again contributed to the political instability of Algeria and made it very difficult to feed people, to take care of basic necessities. It was difficult to feed and to pay the janissaries, the troops, which also led to unrest, and revolts in the capital, and some of the provincial capitals, like Constantine. This again contributed to this very tumultuous time in Algeria, and it was a very difficult for leaders, both in Algiers and in the provincial capitals, to collect taxes and to just manage basic functioning of government.

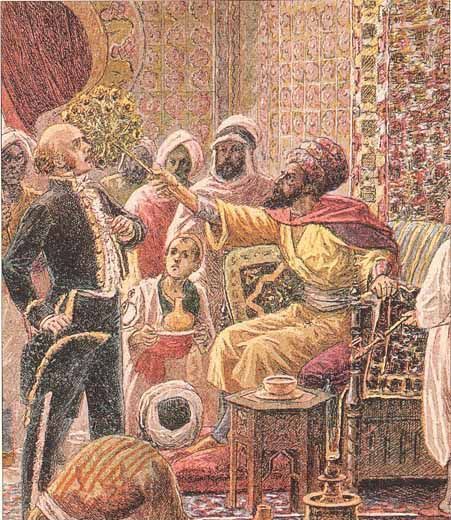

SIÈCLE: Bringing Restoration France into the picture, there is an incident that some people may have heard of with the very picturesque name of the Flyswatter Affair. Can you explain what that is?

SANDERS: Yes, so, to explain what happened, we actually have to go back to 1798, and Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt. Now, you can only conduct an invasion if you can feed your troops, because if you don’t feed your troops, they are likely to desert, and so Napoleon needed to acquire money and to acquire wheat to feed them.

To accomplish this, he contracted with two Jewish merchants in Algiers by the names of Bakri and Busnach, and they helped to fund the French army to acquire the food that they needed for this invasion. Well, they successfully do this, and Napoleon holds power for some time, loses power. But then after his final loss at the Battle of Waterloo, the subsequent French Restoration government refuses to honor these debts, and to pay them.

And so, after years of negotiations, so between 1798 and then finally in 1827, nearly 30 years had passed, and these merchants had still not been paid. The governor himself had also helped to fund the loan to Napoleon. And so together, the three of them were quite upset with the French government about the lack of repayment of this money. And so they talk with the French consul, a man by the name of Deval, and ask him about when they will be paid, and the consul’s response was something to the effect of “King Charles X will not deign to negotiate with you about these lowly matters,” and the governor of Algiers was so incensed, as the story goes, he struck the consul across the face with his flyswatter.

And so, after years of negotiations, so between 1798 and then finally in 1827, nearly 30 years had passed, and these merchants had still not been paid. The governor himself had also helped to fund the loan to Napoleon. And so together, the three of them were quite upset with the French government about the lack of repayment of this money. And so they talk with the French consul, a man by the name of Deval, and ask him about when they will be paid, and the consul’s response was something to the effect of “King Charles X will not deign to negotiate with you about these lowly matters,” and the governor of Algiers was so incensed, as the story goes, he struck the consul across the face with his flyswatter.

Right: Algerian Dey Hüseyin bin Hüseyin strikes French consul Pierre Deval with a flyswatter. Unknown artist, c. 1827. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

SIÈCLE: I imagine this didn’t go over well in France.

SANDERS: [laughs] No, no, this led to international embarrassments, and left the French scrambling to figure out what to do in response. And to add insult to injury, the Algerians fired cannon shots over Deval’s ship as it departed. Now thankfully, they were either good or poor enough shots that they didn’t actually hit the ships, so no one died, but this again was just further insult and contributed to the embarrassment that France suffered in Algeria.

SIÈCLE: And what year was this?

SANDERS: This was in 1827

SIÈCLE: Did this lead to anything in the immediate aftermath?

SANDERS: In the immediate aftermath, France sent another ambassador to try to smooth things over, but things still did not go well in the negotiations between Algeria and France at the time because Algeria’s stance was very simple and very firm: that France needed to honor and repay these debts, and with the accrued interest, and France refused. And so that led to another very similar incident in which the ambassador had to depart under cannon fire, and again, no shots hit the ship or anyone aboard, but again contributed to the rising tensions between these two political entities that had previously had reasonably cordial relationship over the previous 300 years. France had been sending consuls; they had businesses in Algeria that ran relatively smoothly, certainly far more smoothly than relations with any of the other European powers, so it was kind of surprising to see the breakdown in diplomatic relations at this point.

SIÈCLE: Does this appear to have been an incidental breakdown of diplomatic relations, or was one side or the other intentionally trying to raise tensions?

SANDERS: My understanding is that it was incidental. There was unrest in both polities. In France there was already social unrest, political unrest, and you see similar things happening in Algeria at the same time, and it just seemed to be kind of a serendipitous and unfortunate confluence of events.

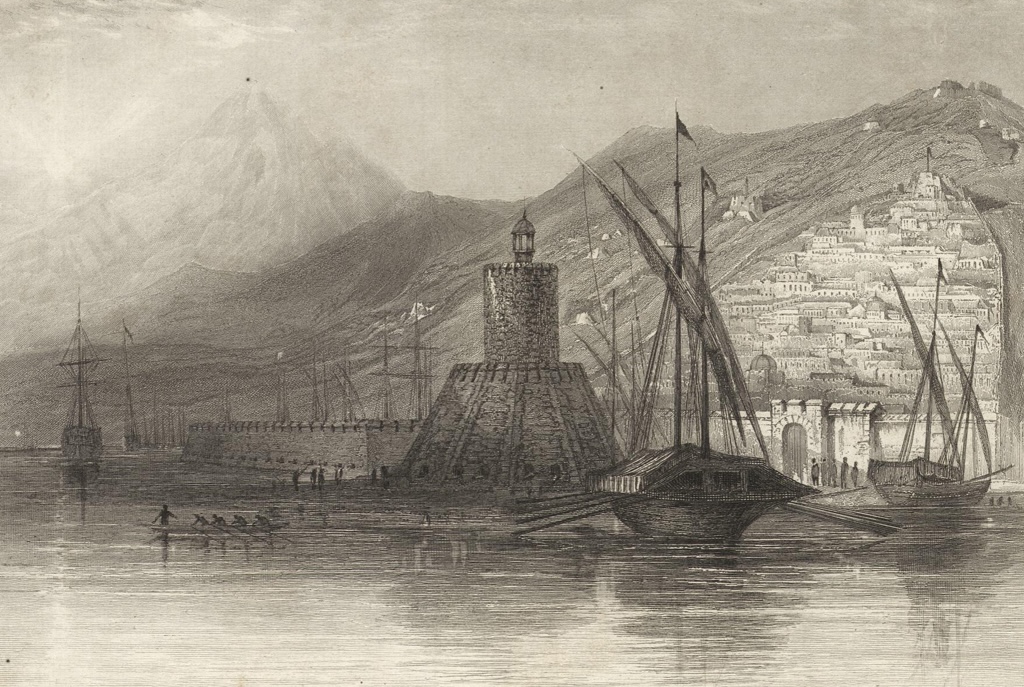

The port of Algiers, mid-19th Century. Unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

SIÈCLE: You talked about the prior close ties between Algeria and France. I imagine that Marseilles and other southern French ports had some reasonably close economic ties with Algeria that were sort of on the line when tensions went high between these two places.

SANDERS: Exactly. There was a very close relationship between Marseilles and particularly this agency responsible for the coral reef fisheries in Algeria. They had businessmen that went back and forth across the Mediterranean between Algeria and France frequently. There were many businessmen who traveled from Algeria to relocate to Marseilles to keep those ties close, and the consuls, the political ambassadors that the French government sent, also worked very closely with merchants in Marseille and located in Algeria as well. And so you see this close tie between commerce and politics that linked these two polities very closely together.

SIÈCLE: You just laid out a fairly comprehensive picture of what Ottoman Algeria was like. Has the picture you laid you always been the conventional understanding, or has there been new research that has shed new light on what Algeria was like in the late 18th and early 19th Century?

SANDERS: That’s a great question. So, beginning in the 19th Century, many French historians were very curious about Algeria’s past, and I will mention that their primary interest in Algeria was actually as a Roman province. The relationship between Europeans and North Africans has been long standing, and so the French were very intrigued by that. So they actually spent more time exploring that past, but they began to get curious about what Algeria was like under the Ottomans — but often for sort of polemical purposes, to show that the Ottoman state was rather tyrannical and that the Algerians were quite oppressed by the Ottomans. And of course that narrative has changed dramatically in the last hundred and fifty years or so.

And now, historians are asking about this complex network of people involved in corsairing and the redemption of captives, what the experience of captives was like. There are a number of captive narratives that have since been published, which has opened up a new picture of what life was like from a European enslaved person’s experience — particularly in Algiers. We don’t get as many views of other parts of Algeria, so I think that’s more fertile ground for additional study.

But we also see scholars such as Joshua Schreier and Julie Kalman who are asking questions about the roles of Jewish merchants and businessmen in Algeria and how they helped to connect Algeria to the larger Mediterranean world. So we have some studies that examine internally what Ottoman Algeria looked like, especially those by Tal Shuval, but we also have studies like those by Schreier and Kalman that are looking at Algeria’s place in the larger Mediterranean through the lens of Jewish merchants that often were really integral intermediaries between the Ottoman leaders in Algeria and European states.

But we also see scholars such as Joshua Schreier and Julie Kalman who are asking questions about the roles of Jewish merchants and businessmen in Algeria and how they helped to connect Algeria to the larger Mediterranean world. So we have some studies that examine internally what Ottoman Algeria looked like, especially those by Tal Shuval, but we also have studies like those by Schreier and Kalman that are looking at Algeria’s place in the larger Mediterranean through the lens of Jewish merchants that often were really integral intermediaries between the Ottoman leaders in Algeria and European states.

Right: “Scene in the Jewish Quarter of Constantine,” by Théodore Chassériau, 1851. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

SIÈCLE: Speaking of modern historians, you yourself have done quite a bit of research into Ottoman Algeria. Can you talk a little about some of the specific topics that you have researched, and some of the discoveries that you have made?

SANDERS: I would be happy to. So, I mentioned Tal Shuval, he focuses primarily on the capital of Algiers in his research, and he was particularly interested in Ottoman identity and ideologies. And so I’ve expanded on his work to ask about similar kinds of questions with Ottoman governors, but in this provincial city of Constantine.

Constantine was quite heterogeneous and quite cosmopolitan even though it was only a provincial capital, because it had a university and was a center of learning for legal and religious scholars for hundreds of years. And it also became really important both as part of Ottoman Algeria, and later because that region is so fertile and was primarily responsible for a lot of the exports of agricultural products. And so, I became really curious about how governors ended up in this province, and how they, how they ruled and what factors influenced their ability to rule effectively.

So I’ve done some what’s called a “prosopographical study,” it’s a big fancy word that basically means you take a bunch of biographies of people, and you extract data about them. And when you analyze that data, quantitatively and qualitatively, you can get a picture of — for example, one of the things I was curious about is what a representative governor looked like: how long was he in office, how did he get there, what other roles did he have, and did he marry into local Algerian families, and if he did, were his outcomes and office different from those who did not marry into local families?

What I discovered is that those who did marry into local families often remained in office much longer, and the end of their term was simply usually their natural death. Those who did not marry into local families often had much less happy endings to their stories, and were frequently assassinated or exiled because they didn’t have the support of the local community.

And seeing how important these marriages were, I really began to ask about the roles of women, because this remains an open area for research. To my knowledge, there is only one book that has been published on women in Algeria during the Ottoman period, and that’s in Arabic. We have no other studies that have even brought up this question. This is really fertile ground to start digging into what was the life of an Algerian woman like? What was their role in society, and even in politics? And if we have time, I can tell you some of those stories that I’ve been able to unearth.

SIÈCLE: I think we’ve got a few more minutes, so I’d love to hear a little bit more of some of these findings.

SANDERS: I’ll tell you one story that really captured my interest. So, many of the women I have found in my research remain unnamed. They were simply referred to as the “daughter of Ahmed,” or the “wife of Salah,” but there are a few women who really stand out because they were named, and we actually know quite a bit about their lives.

So, this takes us, this story that I’m about to tell, takes us all the way back to the end of the 17th Century, and we enter this story with the marriage of one of the Constantinian governor’s daughters, her name was Hani, and she married into a really powerful tribe. This was a frequent way to create political ties and peace treaties between ruling families was to engage one’s children in marriage to the children of the other ruling power. And so, Hani marries a local sheikh, and they form their own family.

It’s a long complicated story, but what eventually ends up happening is her husband has Hani’s brother murdered on a hunting trip. Hani is so furious at the loss of her brother, she has her husband and his whole family killed.

But she doesn’t stop there. She actually takes over the leadership of the tribe itself, and when they went into battle, there are still stories being told about her: that she led the tribe into battle herself on a donkey, using a stick to point to where the troops were supposed to go. And she was such a powerful, fierce woman, that the next Ottoman governor to come to power after her father was trying to contend with this very rebellious tribe led by Hani. And again we see marriage come into play as the most important tool to bring about peace in a region. So Hani’s tribe was rebelling against the next governor, and refusing to pay taxes, and so finally the governor himself has to travel up to Hani, and offers to marry her daughter. She consents to the marriage, and finally peace is re-established, but she held power with that tribe for a number of years. So we have at least one example of a really powerful woman in a position we don’t often think about Algerian women holding at this time period.

SIÈCLE: And if listeners want to learn more about this, have you published about Hani?

SANDERS: Yes I have. So I have a current work out called “Silent No More,”” and I’ll provide a link to that so that will appear in the show notes. Thankfully for those readers who don’t like super long explanatory essays, this one is quite short. It’s only 2,000 words, but you’ll get some of these stories, Hani’s as well as several other really powerful women who not only like Hani led troops into battle but also served as political advisors to their Ottoman governor husbands. So you can read more about them in that article.

My dissertation goes into some of this backstory that I’ve provided, if you want more of the picture of Algiers, and even what it looked like to those arriving in the early 19th Century. They have very wonderful, evocative descriptions of what Algiers looked like and felt like and sounded like during this time period. My first chapter in my dissertation is a great place to go, I can provide a link to that.

And I also have a new book coming out this spring, called Visualizing History’s Fragments, and it brings together these stories that I’ve hinted at, about the governors of Constantine, about the women in their social networks, and brings those to life by analyzing the data about their lives, and so that will be coming out probably March or April 2024.

I will also have a series of articles coming out about both French and Algerian women and their roles in Ottoman Algeria in the 17th through 19th Centuries that will be coming out over the next year, along with one more article about the role of Jewish actors in the eastern province of Constantine, which is a region that hasn’t received a whole lot of attention in terms of the Jewish people living in the Eastern and opposed to the western part of Algeria.

SIÈCLE: Well that is a lot of publication, and for any listeners who have been frantically trying to scramble out notes, don’t worry, if you go to thesiecle.com, I will have links gathered to all of these works, or at least the ones that have been published already, and will try to update the webpage as these come out in the coming year. Any parting thoughts you want to leave people with about the state of Ottoman Algeria leading up to the very interesting year of 1830?

SANDERS: I think we’ve covered the high points. I’m afraid to say more, because that gets us into the details and weeds, and if people are really interested in that level of detail, I can provide links to other publications as well as my own that will help satisfy some of that curiosity.

SIÈCLE: Professor Ashley Sanders, thank you so much for coming on the show.

SANDERS: Thank you so much for having me.

That concludes this exploration of Algiera, brought to you by Evergreen Podcasts and The Siècle’s 119 Patreon supporters. But don’t worry — we’re going to be back. Charles X and his embattled prime minister, Jules de Polignac, will turn their eyes across the Mediterranean Sea in the summer of 1830. But they’ll have to watch their backs, too, because the French political situation in 1830 is anything but stable. When we last saw Charles, he had just prorogued the French parliament after the Chamber of Deputies challenged his speech opening the 1830 session. Next time, Charles is going to go head-to-head with that insolent majority, in Episode 38: The 221.