Episode 39: The Four Ordinances

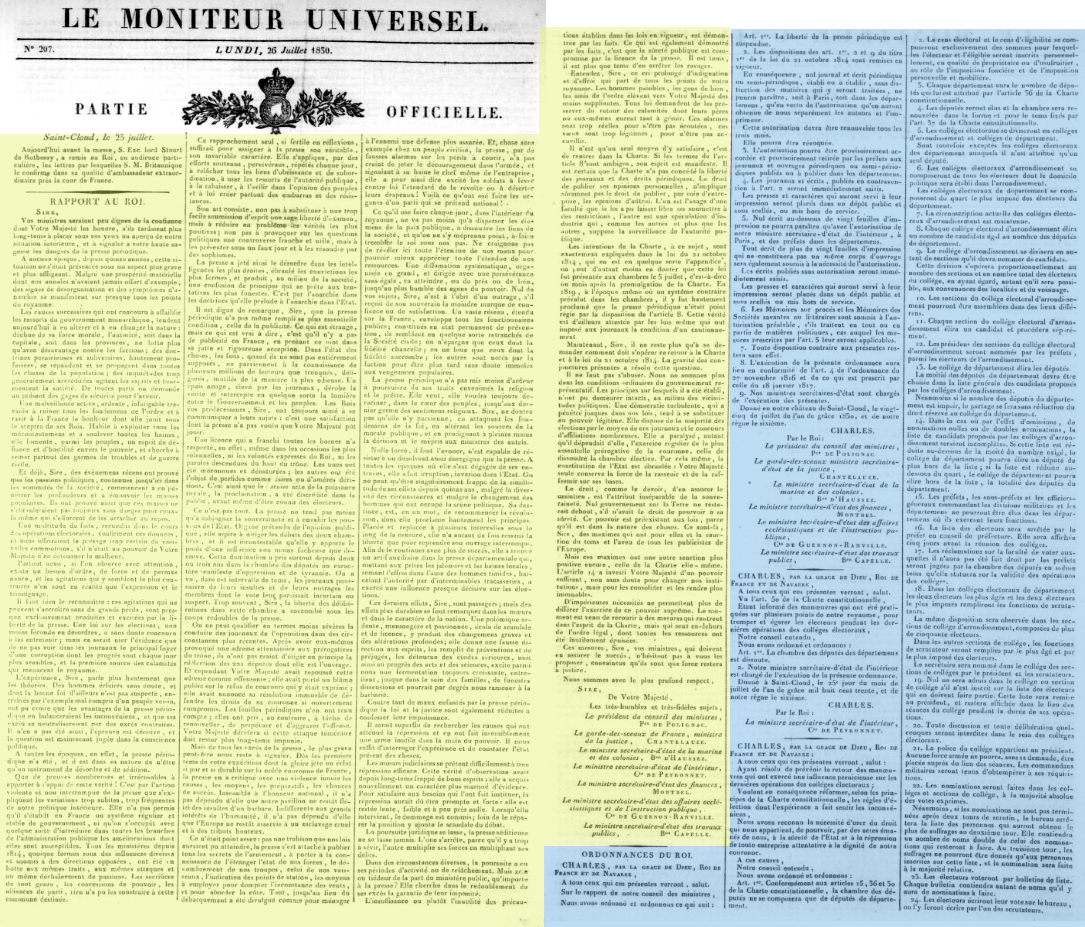

On the morning of July 26, 1830, Parisians woke up to find that the sleepy official government newspaper, Le Moniteur universel, contained a bombshell. A lengthy official notice from the ministry of King Charles X announced four royal ordinances of breathtaking audacity.

On the morning of July 26, 1830, Parisians woke up to find that the sleepy official government newspaper, Le Moniteur universel, contained a bombshell. A lengthy official notice from the ministry of King Charles X announced four royal ordinances of breathtaking audacity.

The reaction of Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans, was fairly typical for members of France’s political elite. Louis-Philippe burst into his wife’s dressing room on the morning of July 26, waving his copy of the Moniteur as she did her hair for the day. “Well, my dear, they’ve done it, they’ve mounted a coup d’état!” the duke exclaimed.1

Right: Louis-Philippe, by Ary Scheffer, 1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Today, five years to the day after I released Episode 1 of The Siècle on January 22, 2019, I’m very excited to be able to finally say the following words:

This is The Siècle, Episode 39: The Four Ordinances.

The publication of the Four Ordinances, with their sweeping assertion of royal authority, is a watershed moment in 19th Century French history. The immediate reaction to the Ordinances will be shock, panic and confusion, followed shortly by — well, we’ll get to that soon enough.

Today I want to set aside the question of what people did in response to these Four Ordinances, to focus on what they were. What exactly did Charles declare by his royal authority? Did he have the authority to declare them? And why were these particular four ordinances the weapons Charles unleashed in his battle with the liberal opposition in the Chamber of Deputies?

Only by understanding these questions will we be in a position to understand everything that happens next. And a lot is going to happen next.

Before we get going, my thanks to everyone who has helped make The Siècle a success over the past five years. That includes nearly 200 people who have backed the show on Patreon at one point or another, and especially new patrons Mark Chapman and Justin Shoffstall. They and every other patron receives an ad-free feed. I also want to thank the countless others of you who have shared the show with your friends and family or reviewed it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and other sites. Word of mouth is how a show like this grows, and I thank you.

I’ll have a special 5th Anniversary special coming out very soon, in which I answer a number of questions that you submitted. Thank you.

As always, I also want to tell you that The Siècle is a member of the Evergreen Podcasts network.

The Six Ordinances?

I want to start my discussion of the Four Ordinances with a bit of pedantic trivia. The July 26, 1830 edition of the Moniteur actually contained six royal ordinances. But the Fifth and Sixth July Ordinances were utterly mundane appointments of 15 different men to positions on Charles’s advisory Council of State, so by unspoken agreement historians pretend these don’t exist and talk only about the Four Ordinances that matter.2

Also, just to clear up any confusion: an “ordinance” in this case is a royal decree, issued from the monarch’s own authority. It’s not exactly a law, which has to be passed by a legislature like the French Chambers, but it has a comparable effect. For American listeners, the closest parallel would be a presidential “executive order.”

Let’s start by reviewing the Four Ordinances themselves. Here’s an extremely brief summary:

- The First Ordinance imposed a temporary state of press censorship

- The Second Ordinance dissolved the newly elected Chamber of Deputies before it even had a chance to meet

- The Third Ordinance imposed a new system of electing the Chamber of Deputies

- The Fourth Ordinance set the upcoming elections, under the new system, for September

Some of these ordinances are more important than others. So let’s start with the straightforward ones: the Second and Fourth.

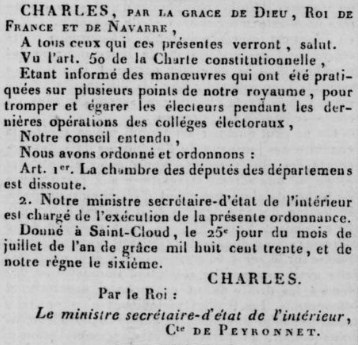

The Second Ordinance

The Second Ordinance is very straightforward, at least on the surface. It has a brief introduction and two articles. Since it’s so short, I’ll just read it in full:

To all whom it may concern:

Pursuant to Article 50 of the Constitutional Charter, and

Being informed of maneuvers that have been practiced in several places in Our kingdom, to deceive and mislead voters during the recent voting in the electoral colleges,

By and with the advice of Our Council [of Ministers], We hereby decree as follows:

Article 1: The Chamber of Deputies of the departments is dissolved.

Article 2: Our Minister of the Interior is charged with executing this ordinance.

Given in our château of Saint-Cloud, July 25 of the Year of our Lord 1830, the sixth year of our reign.

CHARLES3

Setting aside the legalese, the first key statement there is, “Pursuant to Article 50 of the Constitutional Charter.” That article states:

Setting aside the legalese, the first key statement there is, “Pursuant to Article 50 of the Constitutional Charter.” That article states:

The king convokes the two chambers each year: he prorogues them, and can dissolve that of the deputies of the departments; but, in that case, he must convoke a new one within the space of three months.4

There are no explicit restrictions placed on that royal power to “dissolve that of the deputies.” The king is not limited to doing so only for particular reasons or at particular times.

There will be debate in the aftermath of the Second Ordinance about whether the king’s power to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies applies to a Chamber that has not yet convened. The Elections of 1830, as we saw in Episode 38, returned a Chamber of Deputies made up of nearly two-thirds opposition deputies. But on July 25, when Charles signed the Second Ordinance, that newly elected chamber had not yet convened. That was scheduled for August 3.5

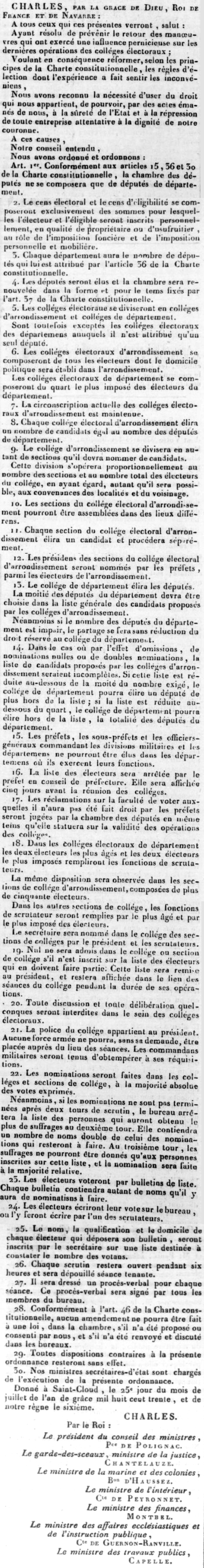

Above: The printed text of the Second Ordinance from the July 26, 1830 edition of the Moniteur universel. Public domain via RetroNews.

Even most opposition deputies might concede Charles had a legal right to dissolve the Chambers after they convened on August 3. But he hadn’t waited. That alone, for some, made the Second Ordinance null and void.6 And even if one conceded that Charles was within the letter of the law to dissolve the Chambers, that didn’t mean he was within the spirit of the law to dissolve a duly elected Chamber just because he didn’t like the men who had won. Even some Ultraroyalists thought the proper thing to do was for Charles to wait until the Chambers did something objectionable before dissolving them.7

That’s not what Charles did here. Instead, he cited unspecified “maneuvers… to deceive and mislead voters during the recent voting.” Now, one person’s “maneuvers to deceive” is another person’s “campaigning for election.” The liberal Globe newspaper defended the role of the opposition in the 1830 election as a “healthy state of constitutional progress.”8 Even today plenty of candidates for office insist their opponents are engaging in lies and mudslinging while they are simply informing the voters about important issues. So it’s hard to take this justification too seriously here. It is worth noting that opposition newspapers in the 1830 election did get up to some questionable stuff, including publishing military secrets about the pending invasion of Algiers.9

The broader question was how much this legal wrangling mattered. After all, Charles had just dissolved the last Chamber of Deputies, and saw liberals only expand their majority. Why would a second go-round be any different? Well, that’s where the First and Third Ordinances come in. But before we get to them, we need to deal with the Fourth Ordinance. Fortunately, this won’t take long.

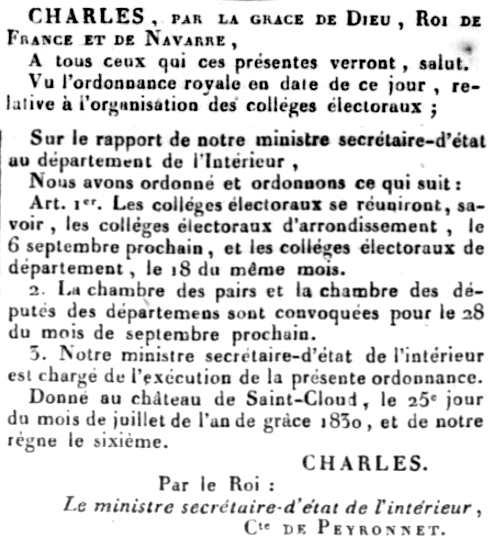

The Fourth Ordinance

The Fourth Ordinance is basically a corollary to the Second. Article 50 of the Charter says the king has to convene a new Chamber of Deputies within three months of dissolving the old one. So Charles was doing so. The Fourth Ordinance set two rounds of elections for September 6 and 13, and convened this newly elected parliament on September 28 — just over two months after dissolution. If you accept the legality of the dissolution in the Second Ordinance, then the Fourth is just a formality. If you don’t accept the Second Ordinance as valid, then the Fourth is irrelevant. So we can just move on.10

The Fourth Ordinance is basically a corollary to the Second. Article 50 of the Charter says the king has to convene a new Chamber of Deputies within three months of dissolving the old one. So Charles was doing so. The Fourth Ordinance set two rounds of elections for September 6 and 13, and convened this newly elected parliament on September 28 — just over two months after dissolution. If you accept the legality of the dissolution in the Second Ordinance, then the Fourth is just a formality. If you don’t accept the Second Ordinance as valid, then the Fourth is irrelevant. So we can just move on.10

Right: A composite image of the printed text of the Fourth Ordinance from the July 26, 1830 edition of the Moniteur universel. Public domain via RetroNews.

The First Ordinance

The really interesting ordinances are the First and Third. They represent, in effect, the way that Charles intended to win the new round of elections called for by the Second and Fourth ordinances. He had tried using the authority of the Church to persuade voters. He had tried to use his own authority to persuade voters. He had tried to use a glorious military conquest to persuade voters. In the elections of June and July 1830, none of that had worked, as I covered in Episode 38. So now Charles was turning away from persuasion to throwing legal barriers at the opposition.

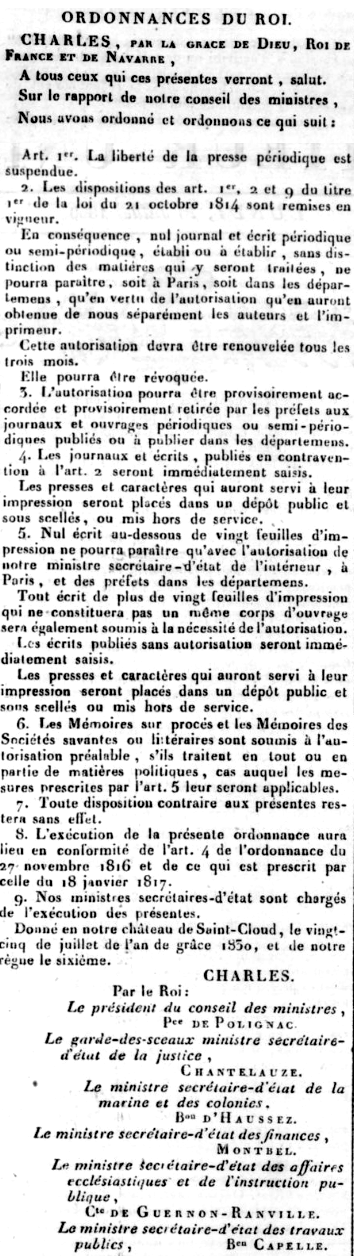

The First Ordinance contains nine articles. A few of them are more technical, but here’s the important stuff:

Article 1: The freedom of the periodical press is suspended.

Article 2: … No newspaper or periodical or semi-periodical publication, already established or to be established, regardless of their subject matter, may appear either in Paris or the departments, except when authorized by us… This authorization must be renewed every three months. It can be revoked.

Article 4: Newspapers and writings published in violation of Article 2 will be immediately seized.

The presses and type which will have been used for their printing will be placed in a public deposit and under seal, or put out of service.

Article 7: Any [legal] provision contrary to this document is null and void.11

This is sweeping, across-the-board censorship. Every French newspaper would now require government authorization to publish — authorization that could be denied for any reason, and withdrawn at any moment. Violations would be punished by not merely seizing the contraband issues, but by seizing or destroying the expensive presses used to print the newspapers.

The First Ordinance was the latest swing in the Bourbon Restoration’s back-and-forth pendulum of newspaper censorship. At times, France had had fairly strict censorship — such as 1815 to 1819, 1820 to 1821, and 1827. At other times, it had fairly liberal press laws, including 1819, and 1828 to 1830. I’ve discussed some of these different provisions in Episode 15, Episode 22, Episode 31 and Episode 33. The exact details aren’t as important as understanding the context of a long-running French debate about whether and how the press should be controlled.

The First Ordinance was the latest swing in the Bourbon Restoration’s back-and-forth pendulum of newspaper censorship. At times, France had had fairly strict censorship — such as 1815 to 1819, 1820 to 1821, and 1827. At other times, it had fairly liberal press laws, including 1819, and 1828 to 1830. I’ve discussed some of these different provisions in Episode 15, Episode 22, Episode 31 and Episode 33. The exact details aren’t as important as understanding the context of a long-running French debate about whether and how the press should be controlled.

Right: A composite image of the printed text of the First Ordinance from the July 26, 1830 edition of the Moniteur universel. Public domain via RetroNews.

But while France had had strict censorship in living memory, it was coming off several years of a relatively free press. The 1828 Martignac press law had left newspapers free to publish what they wanted without having to get approval from a censor. It also abolished a prior law that allowed the king to unilaterally impose censorship when the Chambers weren’t in session. (If you’re wondering how Charles is doing just that now, be patient — we’re getting there.) Newspapers were still subject to libel laws, and had to put up “caution money” as a down payment on potential fines. But the net effect was to allow papers to publish a wide range of articles on political topics without limitation.12

Now France was going from a relatively free press to arguably the most censored press the Bourbon Restoration had seen. Because the First Ordinance showed the French government learning from its past experiments with censorship.

For example, newspapers had tried all sorts of tricks to get around the censor. If they got caught, the newspaper might be fined and maybe the editor jailed. These threats hadn’t deterred opposition papers, who continually tested what they could get away with. Some even had the sentences against them overturned by the courts. So now Charles was imposing a new penalty: the presses that had printed the offending issues would be immediately seized or destroyed. Not only did this impose an immediate penalty that couldn’t be reversed by a judge later, it also spread the pain more broadly: now printers had their own livelihood at risk for agreeing to print opposition papers.13

Likewise, the censorship requirement applied to all newspapers, “regardless of their subject matter” or whether they were already established. A prior censorship law had imposed sharp restrictions on new papers, but journalists discovered a loophole and revived an old defunct newspaper to the government’s helpless fury.14 There would be no more of that. Similarly, because old censorship laws had exempted reporting on criminal proceedings, legal newspapers like the Gazette des Tribuneaux had been able to get away with inserting liberal commentary in their court coverage. That was gone now — Article 6 specifically subjected accounts of trials to censorship “if they deal in whole or in part with political matters.”15

The First Ordinance wasn’t just first in number. It was also first in the hearts of Charles and his ministers, as can be seen from the lengthy essay justifying the Four Ordinances that preceded them in the July 26, 1830 issue of the Moniteur universel. This essay was so long that the Four Ordinances themselves didn’t appear until one-third of the way down Page 2, and the essay made it clear what was to blame for France’s problems:

These agitations… are almost exclusively produced and stimulated by the freedom of the press… It would deny the obvious to not see newspapers as the main source of a corruption whose spread is more noticeable by the day, and as the primary source of the calamities that menace the kingdom.16

A composite image of the first two pages of the July 26, 1830 edition of the Moniteur universel. The area highlighted in yellow is the “Rapport au Roi” justifying the Four Ordinances, while the area highlighted in blue is the First, Second, and part of the Third ordinances. Public domain via RetroNews.

This crackdown was intended to nullify a huge advantage that powered the liberals’ recent electoral victories: all of France’s most popular newspapers sided with the opposition.

That included the two most popular papers in France, the center-left Le Constitutionnel and the center-right Journal des Débats, as well as a host of smaller papers. Overall liberal papers had more than 50,000 subscribers, while Ultra papers had fewer than 20,000.17 These opposition newspapers had bombarded Charles’s ministers, the Catholic Church, and ultraroyalists in general with a steady stream of attacks. They had coordinated the opposition electoral campaign, including publishing detailed electoral guides to help voters foil government vote-rigging.18

Censoring the press would remove a key opposition weapon, and might just help Charles win the fall elections when his candidates had lost the summer voting. Or maybe not — most of the 1827 campaign had unfolded under strict newspaper censorship, too, and the opposition had still scored a shocking victory. Repealing censorship had in fact been one of the key issues for the opposition in 1827, as I covered in Episode 31, so it was possible this could backfire as an electoral tool. Either way, Charles and his ministers seem to have sincerely believed censorship was necessary in 1830, not just politically expedient.19

Besides, they had another tool to help them win the new elections.

The Third Ordinance

Meet the Third Ordinance. While the First Ordinance seems to have been the most important for Charles and his ministers, from our perspective in hindsight the Third is by far the most significant. Because it’s the Third Ordinance that had all the trappings of a coup d’état — unilaterally suspending the constitution, purging the opposition from power, rigging the coming elections and curtailing parliament’s power.

The Third Ordinance had a full 30 articles, a sign of its scope and significance. Many contain massive changes to the functioning of French elections and government in just a few words. So as before, I’ll break down the most important bits — though here, I’ll walk through it slowly, because there’s a lot going on.

First of all, Charles kicked things off with a few sentences of preamble:

To all whom it may concern:

Being resolved to prevent the return of the maneuvers that exercised a pernicious influence on the prior operations of the electoral colleges, and

Wanting therefore to reform, in accordance with the principles of the Constitutional Charter, the election rules whose disadvantages have been shown by experience,

We have recognized the necessity of using Our intrinsic right to provide, via acts emanating from Us, for the security of the state and the repression of all actions detrimental to the dignity of Our crown.

For these reasons, by and with the advice of Our Council [of Ministers], We hereby decree as follows…20

You’ll notice two key things in tension there. First, Charles invokes the Charter. This is not a wholesale repudiation of the idea of constitutional government in favor of absolute monarchy. But Charles adds a caveat: he is operating not “in accordance with the Constitutional Charter,” but “in accordance with the principles of the Constitutional Charter.” That’s a much more expansive and permissive concept, one that could encompass doing things that are not in accord with the strict letter of the Charter in order to preserve its broader “principles.”

You’ll notice two key things in tension there. First, Charles invokes the Charter. This is not a wholesale repudiation of the idea of constitutional government in favor of absolute monarchy. But Charles adds a caveat: he is operating not “in accordance with the Constitutional Charter,” but “in accordance with the principles of the Constitutional Charter.” That’s a much more expansive and permissive concept, one that could encompass doing things that are not in accord with the strict letter of the Charter in order to preserve its broader “principles.”

Right: A composite image of the printed text of the Third Ordinance from the July 26, 1830 edition of the Moniteur universel. Public domain via RetroNews.

Charles also pairs this brief mention of the Charter with a longer defense of his rights and powers as king — not granted by a constitution, but intrinsic to his position. He is using powers “emanating from” him. His reasons for doing so put the “security of the state” and the “dignity of Our crown” on equal footing. He may not be advocating for a return to an ancien régime-style absolute monarchy, but his rhetoric is gesturing in that direction.

This is not simply rhetoric for the Ordinances, either. In a host of private communications at this time, with both liberals and reactionaries, Charles consistently insisted he respected the Charter and had no intention of abandoning it. For example, a message was passed to Charles from Tsar Nicholas of Russia, a fiercely reactionary man who had no love for constitutions. In the message, Nicholas warned that, “If they discard the Charter, they will be on the road to catastrophe. If the king attempts a coup d’état, the responsibility will be his alone.”21 In response, Charles assured the messenger that he would never attack the Charter.22 Likewise, the Duc d’Orléans had a fascinating conversation with Charles in June 1830, in which Louis-Philippe ventured to tell the king that “outside the Charter there is only disaster and perdition.” And Charles — at least as Louis-Philippe recorded the conversation — agreed:

Yes, disaster and perdition, well said, you’re absolutely right. I’m completely convinced of it — outside the Charter, no salvation, there’s no doubt about that. And I say to you that they can do what they like, they will never be able to make me go beyond the bounds of legality, and I shall stay firmly within the legal order.23

The issue is not that Charles is lying about his support for the Charter. It’s that he means something very different when he talks about the Charter than do most people. Charles was genuinely not proposing to get rid of it. But he was proposing to change it in some pretty fundamental ways, as you can see from a few parts of the Third Ordinance:

- Article 1: In accordance with Articles 15, 36, and 40 of the Constitutional Charter, the Chamber of Deputies will only consist of Departmental Deputies.24

In Supplemental 16, I laid out the history of the Bourbon Restoration’s electoral systems through 1830 — and it’s quite the convoluted history. In short, Restoration elections made use of two levels of electoral colleges: one at the level of the local district or neighborhood, and another at the level of the entire department. But how these two tiers of electoral colleges interacted kept changing. In 1815, the local colleges met to nominate candidates, then the departmental colleges would choose the actual deputies. In 1817, the local colleges got abolished, and the departmental colleges did all the electing. In 1820, both types of colleges elected their own slates of deputies — the local colleges with the full electorate, and the departmental colleges with just the richest 25%.

Now, Charles is abolishing the local colleges again, leaving only the departmental colleges. But remember: under current law, the departmental colleges consist only of the richest 25 percent of voters.

Liberals had howled at 1820’s “Law of the Double Vote,” which let the richest voters choose their own deputies while still voting on the local deputies.25 Now, under Charles’s system, there would be in effect only the wealthy Double Voters. They wouldn’t have two votes any more, just one — but the rest of the electors would effectively go from one vote to none.26

That’s a bit of an oversimplification, as we’ll see. But it is the gist. This law would not guarantee Ultraroyalist parliaments — in the 1830 elections, opposition candidates had won 45 percent of all the double-vote departmental seats. That’s a lot less than the share of local seats the opposition had won, but it does show that the opposition could at least be competitive among the richest 25 percent of voters.27

Or at least, that would have been the case had the Third Ordinance stopped there. But it did not.

- Article 2: The tax requirements to be elected and to vote will consist exclusively of the taxes each candidate or voter owes personally for real estate, or through the contribution personnelle et mobilière.28

That probably confused most most of you. It certainly confused me when I was initially trying to translate this article. To understand it, you need to understand how exactly Restoration France calculated eligibility to vote. This is another topic I covered in detail in Supplemental 16, but to summarize, Restoration voters had to pay at least 300 francs in direct taxes. There were precisely four “direct taxes” in the Restoration: the contribution foncière on real estate (but mostly on land); the contribution personnelle et mobilière which combined a small per-person fee and a tax on the rental value of homes; the contribution des portes et fenêtres, a tax on the number of doors and windows in your home; and the impôt des patentes, a tax to obtain business licenses.29

Article 2 was changing that. Under Charles’s new order, only the first two taxes would count for the 300-franc voting requirement and the 1,000-franc requirement to be a deputy: the land tax and the contribution personnelle et mobilière. People still had to pay the door-and-window tax and their business license fees, but these payments would no longer count toward the right to vote.

Removing the patente, the business license fee, was an especially pointed move. Somewhere between one-tenth and one-third of voters under the old system got their eligibility to vote from paying the patente, and these were largely bourgeois types. Essentially, many businessmen and professionals — who leaned liberal — would lose their right to vote, while large landowners — who leaned royalist — would keep it.30

Just how many people would lose their right to vote by excluding the patente and door-and-window tax is a little fuzzier. Most voters who paid the patente also paid taxes on landholdings, too, and some historians have estimated no more than 10 percent of voters were disenfranchised by this clause. Others have reached figures up to one-third.31

But combine Article 2 with Article 1, which effectively disenfranchised the poorer 75 percent of voters, and now you now have a smaller, richer electorate, with fewer left-leaning professionals and businessmen and more right-leaning landowners.

- Article 13: The departmental college will elect the Deputies. Half of the Department’s Deputies will have to be chosen from the general list of candidates proposed by the district colleges…

The local colleges, where voters who weren’t in the richest 25 percent could participate, still existed, and the bottom 75 percent still had their right to vote there. But these local colleges didn’t elect any deputies any more. Instead, they proposed candidates. The departmental colleges would choose the actual deputies from the local colleges’ recommendations — and from their own ideas. They were only required to take half the nominations they were given.32

The language here was drawn from the 1815 rules, where the local colleges had nominated candidates and the departmental colleges had only been required to use half of the nominees in picking deputies. But in 1815, all voters could participate in the departmental colleges, not just the richest 25 percent. In effect, bringing this provision back served as a hedge against the opposition dominating the local colleges and sending only liberal candidates to the departmental electors. Now right-thinking royalist electors in the departmental colleges could correct any such mistakes by the local colleges, and bring in their own men.

- Article 16: The list of voters will be decided by the prefect in the prefecture council; it will be posted five days before the college meeting.

- Article 17: Claims of eligibility to vote that have not been granted by a prefect will be judged by the Chamber of Deputies, at the same time it rules on the validity of the operations of the electoral colleges.

Back in Episode 31, I talked about how earlier elections in the Restoration had given prefects huge power to manipulate elections by omitting known opposition figures from the voter rolls, and how an 1827 law limited that. In 1827 and after, prefects had to post the voter rolls well in advance of the elections, and omitted voters had ample opportunity to appeal and get reinstated.

That was now all gone. Instead the voter rolls would be posted only five days before the electoral college met — almost no time at all given that many voters had to travel to attend their electoral colleges. And anyone who was rejected couldn’t appeal in time to vote. Instead, these appeals would be considered by the Chamber of Deputies after the fact — too late to affect the election, unless the Chamber decided to reject the result and order a new election in that department.

So the legal provisions that the opposition had used to get registered to vote were now gone. So too, under the First Ordinance, were the newspapers liberals had used to coordinate their voter registration drives. Now the government — run under Charles’s direction by Jules de Polignac — would have a sweeping new power to keep undesirables from voting. One of the government ministers sarcastically quipped that they could simplify things by just declaring: “The deputies of each department shall be selected by the prefect.”33

- Article 28: In accordance with article 46 of the Constitutional Charter, no amendment may be made to a law in the Chamber, if it has not been proposed or consented by Us…

This one sort of gets tucked in here near the end of the Third Ordinance’s 30 articles, but it’s huge. Well, potentially huge. On top of unilaterally rewriting France’s election rules, Charles was also limiting an established power of the French parliament to amend laws.

Interpreting this one is a little tricky, though, because Charles wasn’t stretching things here. Article 46 of the Charter actually did say that the Chambers weren’t allowed to amend laws unless it was “proposed or consented by” the King.34 In practice, the Chambers had amended bills all the time. After all, the requirement that the amendments get royal consent could mean nothing because the whole bill requires royal consent to become law.35 If the king doesn’t like an amendment, he can always withdraw a bill. In effect, this was Charles saying, “No amendments, and this time I mean it.” The impact of this article would depend on whether Charles was able to make it stick this time.

- Article 29: Any [legal] provision contrary to this document is null and void.

You may have noticed that on a number of occasions I’ve mentioned a provision overriding a prior law. This is how Charles is doing that — nullifying any old laws that contradict his ordinances.

Okay, so there was a bigger way that Charles was getting around all these pre-existing laws, too. I’ve gone on long enough — let’s talk about the elephant in the room, Article 14 of the Constitutional Charter.

Article 14

I’ve been carefully avoiding mentioning “Article 14” for the past year, to avoid overloading you with terms. I’ve talked about “coups” and “royal powers” and “rule by decree.” All of that has been euphemisms for Article 14, the single biggest loophole in a Charter full of them. Here’s what Article 14 says:

The king is the supreme head of the state, commands the land and sea forces, declares war, makes treaties of peace, alliance and commerce, appoints to all places of public administration, and makes the necessary regulations and ordinances for the execution of the laws and the security of the state.36

Some of that is uncontroversial, even for a republic. Others assert a powerful role for the king in governing. But pay attention to the last bit. The king “makes the necessary regulations and ordinances for the execution of the laws and the security of the state.” Read in one spirit, that’s innocuous — granting the king the power to execute the laws passed by the Chambers and approved by him. Read in another spirit, it grants the king the power to do whatever he wants by royal ordinance as long as it’s in the interest of “the security of the state” — a clause you might remember from the preamble to the Third Ordinance.

For what it’s worth, the men who drafted the Charter over a few quick weeks in 1814 insisted they had never intended Article 14 in such an expansive sense. It was “simply a formula borrowed from previous constitutional precedents without much thought given to it.”37 But that’s not how Charles and his ministers saw things in 1830. The essay that preceded the Four Ordinances in the July 26 Moniteur concluded that “Article 14 has invested Your Majesty with sufficient power not to change our institutions but to consolidate them and render them permanent. Pressing needs no longer allow the exercise of this supreme power to be delayed. The time has come to resort to measures that are within the spirit of the Charter, but outside the legal order — all of whose resources have been exhausted to no avail.”38

For what it’s worth, the men who drafted the Charter over a few quick weeks in 1814 insisted they had never intended Article 14 in such an expansive sense. It was “simply a formula borrowed from previous constitutional precedents without much thought given to it.”37 But that’s not how Charles and his ministers saw things in 1830. The essay that preceded the Four Ordinances in the July 26 Moniteur concluded that “Article 14 has invested Your Majesty with sufficient power not to change our institutions but to consolidate them and render them permanent. Pressing needs no longer allow the exercise of this supreme power to be delayed. The time has come to resort to measures that are within the spirit of the Charter, but outside the legal order — all of whose resources have been exhausted to no avail.”38

Right: Jules de Polignac, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

That’s one of the most fascinating things about the Four Ordinances. Because of the ambiguously expansive wording of Article 14, Charles’s coup may not have even been illegal. It was, to be sure, a violation of Restoration France’s constitutional traditions. But he at least had a fair case to make that Article 14 allowed him to rule by decree in an emergency39 — and the Charter doesn’t specify one way or the other whether “voters repeatedly electing parliaments you dislike” qualifies as such an emergency. Like people did at the time, you can make up your own mind on that.

Until Charles actually pulled the trigger and invoked Article 14 to impose censorship and rewrite France’s electoral laws, this arguably wasn’t even the most controversial article in the Charter. That honor probably went to Article 13, which contains the inscrutable clause that the king’s “ministers are responsible” but doesn’t say to whom the ministers are responsible. Are they responsible to parliament, like the liberal opposition assumed? If so, then the king could not appoint ministers who couldn’t command support in parliament. On the other hand, if the ministers were responsible to the king, like the ultraroyalists assumed, then the king could appoint whoever he wanted. Or perhaps it was some mixture of both? This poorly drafted article had undergirded the entire past year of political conflict over Polignac’s unpopular ministry.40 But now Article 14 threatened to make Article 13 moot: the Chamber of Deputies wouldn’t approve Charles’s ministers, but instead of changing his ministers, Charles was going to change the Chamber of Deputies.

The deciders

Finally, I want to briefly talk about the process by which we got to the Four Ordinances being printed in the July 26 Moniteur universel. I’ve covered that at a high level in the recent episodes — Charles’s 1828 experiment with a compromise government under Martignac, his 1829 appointment of a hard-line ministry featuring Polignac, and the failed efforts to secure a royalist majority in the 1830 elections. Now I want to take us inside Charles’s cabinet of ministers in the summer of 1830 to see how they arrived at this momentous step.

Right: Jean Claude Balthasar Victor de Chantelauze, unknown artist, 1831. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the Moniteur, there are eight names signing the ordinances. One is the king, Charles X. The other seven are the principal members of Charles’s government, the members of his Council of Ministers. After a final cabinet reshuffle in May 1830, these seven men comprised France’s government:

- Jules de Polignac, the foreign minister. Polignac was also the president of the Council of Ministers — effectively France’s prime minister, though neither he nor any other Restoration prime ministers actually used “prime minister” as a formal title.41 I’ve covered Polignac extensively in recent episodes.

- Jean de Chantelauze, the Minister of Justice and Keeper of the Seals. He was a judge who led the Royal Court of Grenoble, and a royalist member of the Chamber of Deputies. When appointed to the ministry in May 1830, he accepted “without enthusiasm,” and “his colleagues had little enthusiasm for him.”42

- Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez, the Minister of the Navy. In Episode 38, we saw Baron d’Haussez organize an invasion fleet and propose bribing his way to a majority in the Chamber of Deputies. As that suggests, D’Haussez was both a capable and energetic administrator and a ruthless and cynical political operator. Right: Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez, unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

- Pierre-Denis, Comte de Peyronnet, the Minister of the Interior. Peyronnet had previously served as Minister of Justice under the Villèle ministry; he was aggressive but unpopular. The Journal des débats wrote on the occasion of his appointment in May 1830 that he was “a man violent among the most violent, blind among the most blind.”43

- Guillaume, Baron Capelle, was made Minister of Public Works as part of the May 1830 cabinet reshuffle. This had previously been part of the Interior Ministry, but it was separated out to create a spot for Capelle because of his reputation as an expert election manipulator.44 If this reputation was accurate, Capelle’s dark arts didn’t do much good in the summer elections, as we’ve seen.

Guillaume-Isidore, Baron de Montbel, was the Minister of Finance, though in the fall of 1829 he had originally been the Minister of Education and Ecclesiastical Affairs. Aside from his flexibility, Montbel was distinguished for his dedicated loyalty to the former prime minister Joseph de Villèle. Montbel was widely seen as Villèle’s man on the council, and indeed wrote Villèle regular letters keeping him informed on intimate details of the Council of Ministers.45 Right: Guillaume-Isidore, Baron de Montbel. Lithograph after a portrait by Daffinger, 1885. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Guillaume-Isidore, Baron de Montbel, was the Minister of Finance, though in the fall of 1829 he had originally been the Minister of Education and Ecclesiastical Affairs. Aside from his flexibility, Montbel was distinguished for his dedicated loyalty to the former prime minister Joseph de Villèle. Montbel was widely seen as Villèle’s man on the council, and indeed wrote Villèle regular letters keeping him informed on intimate details of the Council of Ministers.45 Right: Guillaume-Isidore, Baron de Montbel. Lithograph after a portrait by Daffinger, 1885. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.- Comte Martial de Guernon-Ranville, took Montbel’s place as the Minister of Education. When appointed, he was a public servant “about whom not much was known except that he was a good royalist and a good speaker.”46 One historian terms him “the only independent character in the Cabinet, a strange fusion of royalist, reactionary, upright lawyer and provincial newspaperman.”47 As we’ll see, Guernon-Ranville has another admirable characteristic: he kept a detailed diary during the summer of 1830 that gives us an invaluable look inside Charles’s cabinet.48

There would ordinarily have been an eighth minister on the council. But the minister of war, Louis Auguste de Bourmont, was off in Algeria commanding France’s successful invading army. His role as war minister was being filled on an acting basis by Polignac.49

As you might recall, that May 1830 cabinet reshuffle that brought in Peyronnet, Capelle and Chantelauze was designed to shore up support for aggressive action like the Four Ordinances. Two former ministers had resigned because they weren’t on board. Before Charles had appointed the three men, they had all been sounded out about their willingness to support the use of Article 14. While none of them put anything in writing, they all “formally agreed to it.”50

As you might recall, that May 1830 cabinet reshuffle that brought in Peyronnet, Capelle and Chantelauze was designed to shore up support for aggressive action like the Four Ordinances. Two former ministers had resigned because they weren’t on board. Before Charles had appointed the three men, they had all been sounded out about their willingness to support the use of Article 14. While none of them put anything in writing, they all “formally agreed to it.”50

Right: Comte Martial de Guernon-Ranville, unknown artist, 1831. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But if all seven ministers were committed to the idea of using Article 14 to take aggressive action, they certainly weren’t committed to any specific plans.

The debate

The first really concrete proposal came on June 29, 1830, when it began to sink in that the opposition was going to win the summer elections. Chantelauze proposed a bold three-step response to his fellow ministers: First, invoke Article 14 to suspend the Charter. Second, unilaterally annul the elections of any deputies who had been among the “221” to challenge Charles that spring. Third, dissolve the newly elected chamber altogether and impose a new electoral system to replace it. Finally, Chantelauze added that as a part of this plan, they should station 30,000 soldiers in Paris to be prepared for any unrest.51

The first really concrete proposal came on June 29, 1830, when it began to sink in that the opposition was going to win the summer elections. Chantelauze proposed a bold three-step response to his fellow ministers: First, invoke Article 14 to suspend the Charter. Second, unilaterally annul the elections of any deputies who had been among the “221” to challenge Charles that spring. Third, dissolve the newly elected chamber altogether and impose a new electoral system to replace it. Finally, Chantelauze added that as a part of this plan, they should station 30,000 soldiers in Paris to be prepared for any unrest.51

Above: Pierre-Denis de Peyronnet, unknown artist, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In its broad outlines, you can see the Second, Third and Fourth ordinances there. But when Chantelauze proposed it on June 29, it was met with “a long silence” and then a host of objections. Guernon-Ranville thought expelling the “221” would leave the Chamber too small to function, and questioned whether a hostile vote in the Chamber of Deputies was enough to justify Article 14. Peyronnet backed him up, saying that “the moment had not come for recourse to extreme measures.”52

Below: Guillaume, Baron Capelle, by Robert Lefèvre, 1812. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One week later, Peyronnet had changed his mind. With the scale of the ministry’s electoral defeat becoming clearer, Peyronnet told the council on July 6 that it was time to invoke Article 14. But instead of a plan along the lines of Chantelauze’s, the interior minister proposed convening a “grand council” of peers, deputies, judges, and other prominent men, and task this council with finding a solution to France’s problems. It was, in effect, the ancien régime institution of an Assembly of Notables. As dissidents on the council pointed out that day, the Assemblies of Notables that Charles’s brother Louis XVI had called in 1787 and 1788 had failed to resolve France’s problems or prevent a revolution. Even Peyronnet abandoned his idea in the course of debate, leading Montbel to suspect that it hadn’t been Peyronnet’s idea in the first place. Polignac — the possible real author — was an enthusiastic supporter, but only d’Haussez joined him. The “grand council” was rejected.53

One week later, Peyronnet had changed his mind. With the scale of the ministry’s electoral defeat becoming clearer, Peyronnet told the council on July 6 that it was time to invoke Article 14. But instead of a plan along the lines of Chantelauze’s, the interior minister proposed convening a “grand council” of peers, deputies, judges, and other prominent men, and task this council with finding a solution to France’s problems. It was, in effect, the ancien régime institution of an Assembly of Notables. As dissidents on the council pointed out that day, the Assemblies of Notables that Charles’s brother Louis XVI had called in 1787 and 1788 had failed to resolve France’s problems or prevent a revolution. Even Peyronnet abandoned his idea in the course of debate, leading Montbel to suspect that it hadn’t been Peyronnet’s idea in the first place. Polignac — the possible real author — was an enthusiastic supporter, but only d’Haussez joined him. The “grand council” was rejected.53

But the ministry was gradually taking a harder line. Only Guernon-Ranville still objected to invoking Article 14; he argued that the king should act firm but reasonable and let the Chamber of Deputies appear to be the bad guys. If the Chamber didn’t back down, they’d eventually do something provocative like rejecting a royal budget. Then Charles could declare an emergency and use his royal powers to protect the kingdom from the obstructionist Deputies. But this argument for restraint met a cool reception. By July 6, the increasing vehemence of opposition newspapers — which included calls for revolution and for a change of dynasty — had pushed most of the cabinet to reject restraint.54

By July 10, Peyronnet presented the ministers with draft ordinances that largely mirror what was printed on July 26. There were decrees instituting censorship, dissolving the Chamber of Deputies, and modifying France’s election law. Chantelauze had taken the lead in writing the censorship ordinance, while Peyronnet wrote the dissolution orders and most of the new electoral rules. The council’s meetings over the next few weeks would be focused on revising these draft ordinances into their final forms.55

That’s not to say that the matters being discussed were small! The future Third Ordinance, rewriting the electoral law, in particular saw a number of dramatic proposals made. Polignac proposed a scheme of electing deputies by economic groups, with businessmen, landowners and professionals all having their own blocks of seats. Guernon-Ranville offered up an even bolder proposal: instead of raising the property requirement to vote, the ministry should lower it. As he saw it, the real enemy of the Bourbon Restoration were the bourgeois middle classes; by letting people who owed as little as 50 or even 20 francs vote, Charles could swamp the bourgeoisie with votes from loyal, salt-of-the-earth Frenchmen. But both proposals were rejected in favor of empowering the wealthiest 25 percent of voters to elect all the deputies.56

The decision

By July 24, Polignac presented revised ordinances to the council for final approval. The ministers voted unanimously in favor of the text, though several were still harboring reservations.57

The next day was Sunday, July 25, 1830. The ministers all went to the palace of Saint-Cloud, six miles west of central Paris, where Charles was staying with his court. The formalized rhythms of court life continued; a few courtiers had been granted the privilege of attending the king after morning mass. In the reception room the courtiers and ministers lingered, waiting for Charles, and some of the courtiers could tell something was up. The ministers “seemed anxious and preoccupied” and kept to themselves instead of chatting. One courtier, the Baron de Vitrolles, was a former minister himself and followed politics closely enough to put two and two together. Vitrolles rushed up to Polignac and a few other ministers and urged caution: “I do not ask you for a state secret, but I plead with you to reflect carefully before you take decisive steps,” he said. “The moment is not well chosen, since the population of Paris is in an excited state.”58

Vitrolles received evasive replies, but Guernon-Ranville was alarmed enough that he sought out the commander of the Paris police, who was also in attendance, for details about the forces available. The commander waved off the concerns: “Whatever you do, Paris will not move,” he told Guernon-Ranville. “Act boldly. I answer for Paris with my head.”59

Finally Charles emerged and went through the court rituals, moving around the room and gracing the attendees with a few royal words. Like his ministers, Charles struck some of those in attendance as preoccupied and rushed. Eventually the forms had been observed, the courtiers were dismissed, and Charles sat down with his ministers and his son, the Duc d’Angoulême, to review the proposed ordinances.60

Finally Charles emerged and went through the court rituals, moving around the room and gracing the attendees with a few royal words. Like his ministers, Charles struck some of those in attendance as preoccupied and rushed. Eventually the forms had been observed, the courtiers were dismissed, and Charles sat down with his ministers and his son, the Duc d’Angoulême, to review the proposed ordinances.60

Right: Louis-Antoine, Duc d’Angoulême. Artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles had his ministers read him the ordinances, then had them read a second time. He then turned to Angoulême and asked his son’s opinion. “When danger is inevitable, you must meet it head on. We either win or lose,” Angoulême replied.61

The king then asked his ministers if they agreed. Perhaps unexpectedly, he heard doubts. D’Haussez told Charles that “we are agreed on the ends, but not on the means.” D’Haussez was all for stern measures, but he was not at all confident that Polignac had taken adequate precautions in case there was a popular blowback.

“So you don’t want to sign?” Charles replied.

D’Haussez answered with resignation: “I’ll sign, Sire, because I would consider it a crime to abandon the monarchy and the king under such circumstances.” Guernon-Ranville, who had consistently urged restraint in the past month’s debates, also clearly had doubts. A few days later he would write that he opposed the ordinances but went along with the will of the council, fearing — like d’Haussez — that it was too late: backing out now would only embarrass the monarchy he served. Montbel, too, harbored some doubts. Only Charles and Polignac were truly enthusiastic about the momentous step they were taking. But in the end, everyone signed. “The more I think of it,” Charles declared, “the more I am convinced that it is impossible to do otherwise.” And he put pen to ink on the Four Ordinances.62

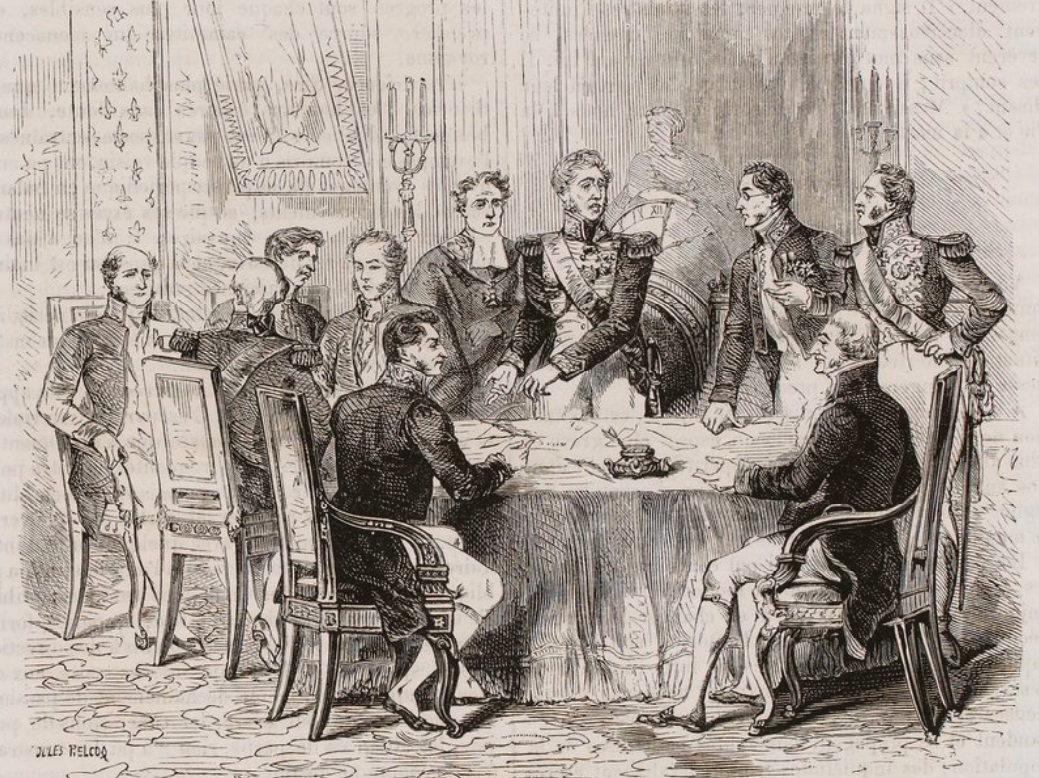

Above: Charles X signs the Four Ordinances, by Jules Pelcoq, 1864. From Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

There remained only one final step. Later that evening, the editor of the Moniteur was called away from dinner with his family by an urgent summons. The editor, François Sauvo, responded promptly, and found Chauntelauze and Montbel sitting in a “dimly lighted” room. Chantelauze handed Sauvo a roll of documents. “Here are some important papers to publish in tomorrow’s Moniteur,” the justice minister said.63

It was 11 p.m., the last possible moment to stop the presses and change the next day’s Moniteur. The delay was part of a bid for secrecy and surprise — a bid that largely succeeded, as we saw with the Duc d’Orléans at the start of the episode. Sauvo was as surprised as anyone as he read the ordinances in silence. Finally, Montbel asked him what he thought.64

“Monseigneur,” Sauvo replied, “after having recognized the purpose of the acts handed to me, I can only reply: God save the King. God save France.”65

Thank you so much again for following this project over the past five years. I truly could not have done it without all of you listening, reading, or sharing the show.

As always, you can visit thesiecle.com/episode39 for a full annotated transcript of this episode — including pictures of all the ministers we talked about today, and of the July 26 edition of the Moniteur containing the Four Ordinances.

You can also visit evergreenpodcasts.com for more great shows from the Evergreen Podcasts network.

Meanwhile, stay tuned. I’ve got a special anniversary special coming out very soon. And when the main narrative picks back up, it’s going to be exciting and action-packed. Rather than give you a birds-eye view of the events that are about to happen, I’m going to take you in to the fog of war and explore the action from the chaotic, confused perspective of the people on the ground, trying to react to what they saw with what they knew. Over multiple episodes, my goal is to weave these different perspectives together to build a full picture — one as little tainted by hindsight as I can manage. And we’re going to start with the very first people impacted by the Four Ordinances as they try to figure out if and how they can resist.

Join me next time for Episode 40: The Journalists.

-

Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 147. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

“French Constitutional Charter of 1814,” Wikisource. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, May 17, 1830. Accessed via Diginole. ↩

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 123-4. ↩

-

Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 324, 343-4. ↩

-

Daniel L. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827-30 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 209. ↩

-

Indeed, the prior ordinance dissolving parliament in May had included both the dissolution and the setting of a date for the new elections in a single ordinance. Le Moniteur universel, May 17, 1830. Accessed via Diginole. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Robert Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition: Liberal Opposition and the Fall of the Bourbon Monarchy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 242. Irene Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 1814-1881 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), 55. ↩

-

The first day that the First Ordinance went into effect, this exact dynamic played out: journalists still wrote their articles, but many printers refused to print them. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 225. ↩

-

Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 46-7. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 22-3. Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. See also Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 221. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 213. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 430. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 221. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 217. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 133-4. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

See Episode 15. ↩

-

Article 6 confirmed Article 1’s implication: That the departmental voters would be only the most-taxed quarter of each department’s voters. ↩

-

Thomas D. Beck, French Legislators 1800-1834: A Study in Quantitative History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 182. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Sherman Kent, Electoral Procedure Under Louis-Philippe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937), 32-41. ↩

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 382-3. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 383. Beach, Charles X, 352. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 353. The quip was said by the Minister of Education, Comte Martial de Guernon-Ranville. ↩

-

“French Constitutional Charter of 1814,” Article 46. Wikisource. ↩

-

For example, in 1827, the Chamber of Peers had drastically amended a government bill on jury lists, “from something which the government desired to something that the government wanted not at all.” Sherman Kent, The Election of 1827 in France (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1975), 20-1. In 1829, an amendment passing on a local government bill provided the excuse Charles needed to fire his prime minister Martignac. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 419. ↩

-

“French Constitutional Charter of 1814,” Wikisource. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 69. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, July 26, 1830. Accessed via RetroNews. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 140. ↩

-

Pinckney 45. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 270. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 430. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 28-9. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 28. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 430. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 426. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 211. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 128. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 441. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 213-4. Beach, Charles X, 344. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 75. Beach, Charles X, 348. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 75. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 75. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 441. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 441. Beach, Charles X, 350. Price, The Perilous Crown, 138. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 77-8. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 74, 77-8. The efforts for secrecy were thorough. As soon as a new draft of the Ordinances was written, the old drafts were destroyed. Polignac kept that sole copy on his person. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 77-8 ↩