Episode 38: The 221

Hey everyone. This is David Montgomery, host of The Siècle. Before we dive in to today’s episode, I wanted to make a quick announcement. I’m writing this on January 2, 2024. And that means that 20 days from now is a special day — exactly five years after I released Episode 1 of The Siècle on January 22, 2019.

The timing for this has worked out amazingly. As you’ll hear in the episode to come, the show’s narrative is building to a huge, climactic confrontation — right on schedule for The Siècle’s fifth birthday.

That’s not the only way I’ll be marking the show’s anniversary, though. And here’s where you come in, if you’re listening to this episode when it comes out. For the show’s fifth birthday, I’m planning a special anniversary episode where a special guest is going to moderate a Q&A — including your questions.

So if there’s anything you want to know about The Siècle, about the Bourbon Restoration, or about me, now is your chance to ask it. Send an email to david@thesiecle.com with your questions by January 13, 2024, and I’ll forward them over to my guest moderator to consider for inclusion. You can write your questions out, or — since this is an audio medium — you can record yourself asking them.

I’m looking forward to a great discussion, and hope many of you will reach out with your questions to be a part of this upcoming birthday celebration.

This is The Siècle, Episode 38: The 221.

Welcome back, everyone. Today we’re returning to our main political narrative of Charles X, Jules de Polignac, and the opposition in the French Chamber of Deputies. I last talked about that in Episode 34, which climaxed in Charles suspending parliament.

Since then, we’ve also covered the dismal state of the French economy in Episode 35; France’s colonial empire in Episode 36; and France’s deteriorating relationship with the North African Regency of Algiers in Episode 37.

Don’t worry: I’m going to take some time to recap everything as I weave all these threads together. But first, I want to remind everyone that The Siècle is part of the Evergreen Podcasts network. Visit evergreenpodcasts.com for more great shows. I’d also like to thank the show’s latest supporters on Patreon: David Turner, Philip Hughes, Scott Goehring, Tom Jurenka, David, Richard Whalen and Gerhard Mehier. They and all other patrons get an ad-free feed of the show.

Visit thesiecle.com/support to join The Siècle’s Patreon, and visit thesiecle.com/episode38 for a full annotated transcript of this episode.

Now, let’s get back in to the story. In the late 1820s, France was in the middle of a slow-moving political crisis. King Charles X’s support for reactionary ultra-royalist policies and fears that he was part of a “clerical plot” ate away at his popularity. So did the ruthless maneuvering of Charles’s prime minister, Joseph de Villèle, who oversaw a series of political successes but alienated former allies in the process. As I covered in Episode 31, a disciplined campaign by French opposition groups led to an unexpectedly strong performance in the 1827 elections, and eventually to Villèle’s defeat.

At this point, Charles agreed with extreme reluctance to appoint a more moderate government, led by the Vicomte de Martignac. Martignac tried to strike a compromise between the king’s ultraroyalism and the center-left majority in the Chamber of Deputies. I covered that in Episode 33. This proved ultimately futile, and in 1829 Charles dismissed Martignac to appoint the government he had wanted all along: one led by close friend and prominent ultraroyalist Jules de Polignac.

Polignac came into office accompanied by other ministers from the far right of French politics, including the turncoat general Louis Auguste de Bourmont as minister of war. The government was so extreme that many people thought it was a prelude to Charles launching a coup to purge the liberal opposition and impose ultraroyalist policies by force.

Instead, as I described in Episode 34, Polignac came into office and promptly did nothing at all. The coup did not materialize, with the ministry puttering along for months as Polignac’s coalition frayed at the edges. Eventually matters came to a head in March 1830, when the Chamber of Deputies voted 221 to 181 to approve a confrontational response to a provocative speech by Charles. In response, the king suspended parliament.

But it’s not quite true that Polignac wasted his first six months in office. Polignac wasn’t doing nothing at this time. He just wasn’t doing much domestically. Instead, Polignac and Charles spent most of their energy in late 1829 and early 1830 focused on foreign affairs.

This makes a certain amount of sense. After all, Polignac’s immediate background was in foreign policy — he had spent the past five years as France’s ambassador in London, and he held the portfolio of Foreign Minister. For another thing, Polignac took office right in the middle of a foreign policy crisis.

The Great Plan

This particular crisis was related to the aftermath of the Greek War of Independence, which I covered in Episode 30. The Ottoman Empire had been defeated in that rebellion when Britain, France and Russia intervened and sunk the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet at the 1827 Battle of Navarino Bay. The next year, Russia declared unilateral war against the reeling Ottomans, and by 1829 the Russian army was advancing deep into Turkish territory. On August 19, 1829, the Russian army took the crucial city of Adrianople, also known as Edirne. This was a week and a half after Polignac had taken office as France’s Foreign Minister. It also left the road open to Constantinople.1

The Ottoman Empire at this time ruled over huge swathes of Eastern Europe and the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean. As the Duke of Wellington — by this point Britain’s prime minister — wrote, if Constantinople fell, “the world must then be reconstructed.” Anything seemed possible as Polignac contemplated a response.2

The response Polignac chose certainly did not lack for boldness. He instructed France’s ambassador to Russia to sound the tsar out about a proposal to dissolve the Ottoman Empire and redraw the map of Europe. Russia would receive Ottoman territories along the eastern and southwestern shores of the Black Sea. Austria would get Bosnia and Serbia. Egypt would become independent, and its ruler Muhammad Ali would take over the Muslim title of Caliph from the deposed sultan. Neither France nor Prussia would gain any ex-Ottoman territory in this proposal, but they wouldn’t be left out in the cold. Instead, Polignac proposed abolishing the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the northern Dutch part falling under Prussian control, and the southern part — Belgium — joining France. The deposed King William of the Netherlands would be compensated with a glittering new throne: of a new Greek Empire ruled from Constantinople.3 As historian Munro Price quips, Polignac’s proposal was “literally Byzantine.”4

The response Polignac chose certainly did not lack for boldness. He instructed France’s ambassador to Russia to sound the tsar out about a proposal to dissolve the Ottoman Empire and redraw the map of Europe. Russia would receive Ottoman territories along the eastern and southwestern shores of the Black Sea. Austria would get Bosnia and Serbia. Egypt would become independent, and its ruler Muhammad Ali would take over the Muslim title of Caliph from the deposed sultan. Neither France nor Prussia would gain any ex-Ottoman territory in this proposal, but they wouldn’t be left out in the cold. Instead, Polignac proposed abolishing the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the northern Dutch part falling under Prussian control, and the southern part — Belgium — joining France. The deposed King William of the Netherlands would be compensated with a glittering new throne: of a new Greek Empire ruled from Constantinople.3 As historian Munro Price quips, Polignac’s proposal was “literally Byzantine.”4

Above: Jules de Polignac, by François Gérard, c. 1814-1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It would be a mistake, however, to view Polignac’s plan as just Polignac being quirky. As Price has chronicled, Polignac’s proposal was merely an unusually brazen move in a years-long project across different Restoration governments to try and undo some of France’s territorial concessions imposed as part of the broader Congress of Vienna. And the crux of these efforts was restoring France’s so-called “natural borders.” That concept referred to a northeastern frontier following the Rhine River, which meant annexing to France territories that today compose Belgium, Luxembourg, and western Germany.5

While the early years of the Restoration saw a chastened France keep its head down in Europe, that started to change after France’s 1823 invasion of Spain — which I covered in Episode 18. When he was foreign minister in 1823 and 1824, Chateaubriand spoke of revising, “by negotiation or by force, the odious Vienna settlement.” The cautious Joseph de Villèle wasn’t so enamored by such schemes, but Villèle’s eventual replacement Martignac was. The Martignac ministry dispatched a new ambassador to Russia in 1828, the duc de Mortemart, with a policy of “giving Russia a free hand in the east” against the Ottomans, with the goal of obtaining later Russian support for French territorial gains in the west. French newspapers openly debated and endorsed this, such as a July 1828 article in the Journal des débats that said France needed no territories in Greece, merely “better and stronger frontiers” at home. Charles X was fully on board, talking to Martignac about the possibility of war against Austria to “end domestic divisions and give the nation wider horizons, as she desires.” Now, in 1829, Polignac saw developing events in the east and decided the time was right to strike.6

But you might have noticed that Polignac’s bold proposal left out one European great power: Great Britain. Technically Polignac did propose to give Britain former Dutch colonies as compensation, but there were no illusions: A proposal like this to tear up the map of Europe and benefit every other remaining great power would in effect have been a bold anti-British alliance, aligning the conservative monarchies of the continent against the isolated British island. “Either we consent to be saddled forever with the treaties of 1815, or we must make up our minds to incur the hostility of England,” Polignac said in a cabinet debate on the topic. “In alliance with Russia, Prussia, Bavaria, and the great part of the rest of Germany, we can force England.”7

France did not end up incurring the hostility of England over this. Indeed, it was never in a position to do so. International geopolitics is never purely about grabbing more territory. Countries and leaders also have what some scholars term “ideological projects,” and both Austrian foreign minister Klemens von Metternich and Russian Tsar Nicholas I shared a belief that Europe’s greatest danger was “the international revolutionary menace.” The political turmoil under Charles convinced Nicholas that France was at risk of falling back into revolution — and thus an unreliable geopolitical partner for Russia. This was especially true, Nicholas thought, if France provoked a new European war over the scraps of the Ottoman Empire. Instead, Nicholas accepted a counter-proposal from the Austrians: Russia would negotiate a peace with the Sultan and work with Austria to keep an eye on France. Ironic though it might have seemed to an arch-reactionary like Polignac, Nicholas saw Polignac’s foreign policy as contributing to the revolutionary menace.8

France did not end up incurring the hostility of England over this. Indeed, it was never in a position to do so. International geopolitics is never purely about grabbing more territory. Countries and leaders also have what some scholars term “ideological projects,” and both Austrian foreign minister Klemens von Metternich and Russian Tsar Nicholas I shared a belief that Europe’s greatest danger was “the international revolutionary menace.” The political turmoil under Charles convinced Nicholas that France was at risk of falling back into revolution — and thus an unreliable geopolitical partner for Russia. This was especially true, Nicholas thought, if France provoked a new European war over the scraps of the Ottoman Empire. Instead, Nicholas accepted a counter-proposal from the Austrians: Russia would negotiate a peace with the Sultan and work with Austria to keep an eye on France. Ironic though it might have seemed to an arch-reactionary like Polignac, Nicholas saw Polignac’s foreign policy as contributing to the revolutionary menace.8

Above: Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, attributed to Franz Krüger, c. 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

When the diplomatic dust settled, Russia halted its offensive and forced the Ottomans to sign the punitive Treaty of Adrianople. Russia got territory along the mouth of the Danube and in the Caucasus Mountains. The Ottomans agreed to pay a huge indemnity to Russia, to let Russian ships pass through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, and to grant effective autonomy to its Balkan provinces of Moldavia and Walachia. In return, Russia ended the war early instead of attacking Constantinople.9

Territorial changes as a result of the Treaty of Adrianople (1829) and Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828). Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Treaty of Adrianople was signed on September 14, 1829 — while Polignac’s grand proposal was still in transit. It arrived as a dead letter, and everyone moved on. The Russians had also forced the Ottomans to finally recognize the independence of Greece, and diplomats for all powers spent months haggling before a February agreement established a free Greece under the rule of a new king, Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.10 Leopold, a well-regarded German princeling and the widower of an English princess, will not actually end up becoming King of Greece — but that’s a story for a future episode.

The Treaty of Adrianople was signed on September 14, 1829 — while Polignac’s grand proposal was still in transit. It arrived as a dead letter, and everyone moved on. The Russians had also forced the Ottomans to finally recognize the independence of Greece, and diplomats for all powers spent months haggling before a February agreement established a free Greece under the rule of a new king, Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.10 Leopold, a well-regarded German princeling and the widower of an English princess, will not actually end up becoming King of Greece — but that’s a story for a future episode.

Right: Portrait of Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, after George Dawe, c. 1818-1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Algiers, part 1

Besides the so-called “Eastern Question,” Polignac also took office facing another, more minor foreign policy crisis. As discussed in Episode 37, conflict had been brewing between France and the quasi-independent Ottoman territory of Algiers. In 1827, the Dey of Algiers, Hussein, had struck the French consul with a flyswatter during a dispute over unpaid French debts. France had responded by imposing a naval blockade on Algiers, but this was ineffective at either stopping trade or resolving the dispute. A second French envoy arrived in 1829 to try to find a peaceful solution, but failed. The Algerians fired cannons in the direction of the parley ship as it left port on August 3, 1829. With the delay in travel, news of this insult reached France right as Polignac was taking office.11

The Polignac government took no major response immediately. He had bigger fish to fry, as we’ve seen. But there was a widespread sense that when France did give the dispute its full attention, it would resolve the dispute violently. Back in 1827, after the flyswatter attack, Villèle’s war minister had proposed an invasion, and noted that besides resolving the diplomatic dispute, an invasion could have domestic benefits: It would “provide a useful distraction from political trouble at home” and “remind [the nation] that military glory survived the Revolution.” In May 1829, under the centrist Martignac ministry, opposition deputies criticized talk of “attempting a conquest in Africa” as a diversion from efforts to regain lost territory in Europe.12

Polignac did explore one possible solution early on — one involving the irrepressible ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali. Ali offered to solve the French dispute with Algiers for them by invading himself, in return for a few modern warships and an advance payment of 20 million francs. Polignac thought this “an excellent idea” that could cheaply and efficiently quash the problem, but Charles wasn’t so sure, and neither were the British or Ottomans. The Muhammad Ali plan was “discarded relatively quickly.”13

Polignac did explore one possible solution early on — one involving the irrepressible ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali. Ali offered to solve the French dispute with Algiers for them by invading himself, in return for a few modern warships and an advance payment of 20 million francs. Polignac thought this “an excellent idea” that could cheaply and efficiently quash the problem, but Charles wasn’t so sure, and neither were the British or Ottomans. The Muhammad Ali plan was “discarded relatively quickly.”13

Left: Muhammad Ali, pacha of Egypt, by David Wilkie, 1841. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

With the failure of Polignac’s proposal to redraw the map of Europe, France found herself in early 1830 with renewed freedom to pay attention to its Algiers problem. And this meant war. By early January, Polignac had already begun preparations, even before the French cabinet formally voted to invade on January 31, 1830. This was over a month before the French parliament convened for its 1830 session — a month before Charles’s controversial March 2 address and the Chamber of Deputies’s defiant response, as I covered in Episode 34.

Preparations for the invasion moved forward on two paths. One was logistic: an actual invasion force had to be prepared. That meant men, ships and supplies. Admiral Guy-Victor Duperré, who was chosen to command the naval expedition, had deep reservations — Algiers had a reputation as being “unassailable.” Duperré insisted it would take at least a year to get everything ready for an attack on such a formidable target. But Polignac’s naval minister, the Baron d’Haussez, was less pessimistic and more energetic — “a man capable of prodding these very timid warriors.” By the end of April d’Haussez had assembled 103 warships, 350 transport ships, 27,000 sailors, 37,000 soldiers, 83 pieces of siege artillery and all the supplies needed to feed and equip the whole expedition.14

Polignac’s triumph

Meanwhile Polignac got personally involved in the other crucial part of preparations: diplomacy. By this I mean not diplomacy with Algiers — that was basically done — but diplomacy with the rest of Europe to make sure the other great powers didn’t stop France.

This was serious business. Britain in particular was fiercely opposed to France expanding its power in North Africa. The year before, Wellington had formally notified the French government that “any change in the status quo in the Mediterranean would incur opposition.” In 1830, he summoned the French ambassador for a dressing down, and tried to rally the rest of Europe to stop the French.15

History does not look kindly on Jules de Polignac’s tenure as prime minister, to put things mildly. But it has to be admitted that the diplomacy over the Algiers expedition in 1830 was a genuine triumph — Polignac at his most effective. Fortified with deep experience from years as ambassador in England, Polignac ran circles around Wellington. Polignac recognized that the Wellington government was on weak ground domestically. The extremely controversial passage of civil rights for Catholics in 1829 had alienated the far-right “High Tories,” while other policies didn’t go far enough for the more liberal faction of so-called “Canningite” Tories. Meanwhile the continent-wide economic recession we discussed in Episode 35 was also battering England, provoking a rise in radicalism and riots from lower classes, and discontent from the country gentry who formed a key part of Wellington’s political base. On top of all that, King George IV spent the early months of 1830 slowly dying.16 Historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny judges that Wellington might well have used force to prevent the French invasion if his government had been on firmer ground. But it wasn’t, and Polignac knew it.17

History does not look kindly on Jules de Polignac’s tenure as prime minister, to put things mildly. But it has to be admitted that the diplomacy over the Algiers expedition in 1830 was a genuine triumph — Polignac at his most effective. Fortified with deep experience from years as ambassador in England, Polignac ran circles around Wellington. Polignac recognized that the Wellington government was on weak ground domestically. The extremely controversial passage of civil rights for Catholics in 1829 had alienated the far-right “High Tories,” while other policies didn’t go far enough for the more liberal faction of so-called “Canningite” Tories. Meanwhile the continent-wide economic recession we discussed in Episode 35 was also battering England, provoking a rise in radicalism and riots from lower classes, and discontent from the country gentry who formed a key part of Wellington’s political base. On top of all that, King George IV spent the early months of 1830 slowly dying.16 Historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny judges that Wellington might well have used force to prevent the French invasion if his government had been on firmer ground. But it wasn’t, and Polignac knew it.17

Above: Extract of a portrait of Arthur Wellesly, Duke of Wellington, by George Dawe, 1829. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

When confronted with British attempts to find a diplomatic solution to the crisis, Polignac’s diplomats adopted a policy of delays and dodges. France’s ambassador in Constantinople couldn’t possibly start work on a peace commission without waiting for instructions from Paris, you see — a delay that stalled the peace mission by a crucial month.18 When Wellington demanded a French promise that the invasion of Algiers would only seek to avenge insults, not conquer territory, Polignac demurred — it would be offensive to the other powers of Europe for France to give a special assurance to just Britain. Meanwhile those other powers were largely OK with the French invasion. In March — during the period between Charles’s March 2 speech to the Chambers and the Chamber of Deputies presenting their response on March 18 — Polignac issued a statement to the other powers of Europe in which he claimed that France’s “aim is humanitarian”:

We are seeking [Polignac wrote], in addition to satisfaction for our own grievances, the abolition of the enslavement of Christians, the destruction of piracy, and the end of humiliating tributes that the European states are having to pay.

Who could possibly be opposed to a humanitarian intervention aimed at suppressing slavery and piracy? Britain itself had attacked Algiers for those exact purposes in 1816, as we discussed in Episode 37. Tsar Nicholas gave his assent to France’s invasion, and the Austrian and Prussian governments followed suit.19

Right: Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez. Unknown artist and date. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The British government, correctly, did not trust these promises. They could see the scale of the fleet d’Haussez was assembling at Toulon. Britain’s foreign minister complained to Polignac that “the formidable force about to be sent… appears to indicate an intention of entire destruction of the Regency rather than the [infliction] of chastisement.” An exasperated Wellington called Polignac “one of the most clever and most dishonest of men.” At the end, the most Wellington’s weakened government could do was deliver a strongly worded protest directly to Charles X. But the king called the British bluff: “Mr. Ambassador,” Charles replied, “all I can do for your government is not to listen to what I have just heard.”20

The King’s favorite

Of course, Polignac’s own government wasn’t exactly the picture of strength during all this. Polignac’s ministry lacked a majority in the elected Chamber of Deputies, which showed itself willing — in dramatic fashion — to clash with the king himself in their effort to fire Polignac.

Charles had refused to abandon Polignac, who was his closest friend as well as sharing most of his beliefs. This loyalty isn’t that surprising. The last time France had a prime minister who was also the king’s personal favorite, it was Élie Decazes under Louis XVIII. And even after a national crisis and the erosion of Decazes’s support in parliament, Louis still resisted pleas to fire Decazes. He didn’t break down until his niece, the Duchesse d’Angoulême, literally got down on her knees and told Louis that Decazes would likely be assassinated if he wasn’t fired. (I covered all that in Episode 14.) And Charles’s relationship with Polignac was certainly that level of closeness. Baron D’Haussez, a loyal supporter of Charles, was forced to concede that, “The relationship between the king and his ministers was not what one would expect in a constitutional monarchy.”21

Charles had refused to abandon Polignac, who was his closest friend as well as sharing most of his beliefs. This loyalty isn’t that surprising. The last time France had a prime minister who was also the king’s personal favorite, it was Élie Decazes under Louis XVIII. And even after a national crisis and the erosion of Decazes’s support in parliament, Louis still resisted pleas to fire Decazes. He didn’t break down until his niece, the Duchesse d’Angoulême, literally got down on her knees and told Louis that Decazes would likely be assassinated if he wasn’t fired. (I covered all that in Episode 14.) And Charles’s relationship with Polignac was certainly that level of closeness. Baron D’Haussez, a loyal supporter of Charles, was forced to concede that, “The relationship between the king and his ministers was not what one would expect in a constitutional monarchy.”21

Above: A lithographic portrait of French statesman Élie Decazes, by François-Séraphin Delpech after Louis Dupré, c. 1828. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Now combine that with genuinely unsettled questions about royal prerogative in the Bourbon Restoration’s constitutional monarchy, and the king’s beliefs that the opposition was spreading “perfidious insinuations” and threatening “the rights of my crown,” and it’s understandable why Charles refused to back down.

But merely not backing down wasn’t an option. Under the Charter of 1814 that governed the Bourbon Restoration, “No tax can be imposed or collected, unless it has been consented to by the two chambers.” Unless Charles and Polignac were going to abolish the Charter — which neither man endorsed in public or in private at this time22 — they needed a Chamber of Deputies. They just didn’t want this Chamber of Deputies.

Fair enough. Charles had an undisputed power under the Charter to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and call for new elections — something the king firmly intended to do after in 1830 after the Chamber of Deputies challenged his speech.

The problem was that the liberal opposition had done really well in the Election of 1827, and had continued to do well in special by-elections held in the years since. There was every indication that if Charles called new elections, the opposition would maintain or even expand its majority — putting Polignac worse off than before.

Charles and Polignac, in other words, needed to do something to change the political dynamic, to make a hostile electorate vote for pro-Polignac deputies. And by the time Charles officially dissolved parliament on May 16, 1830, they had a plan to do just that.

The Villèle Gambit

That plan did not involve making significant policy concessions to win over moderate opinion. As Charles saw things, he had tried that with Martignac, an effort that had ended with the king declaring, “There is no way to come to terms with these people.”23

It also did not involve widespread bribery. That, at least, was seriously considered. The practical Baron d’Haussez declared at a ministerial meeting that “with 40,000 francs he could purchase 40 votes and give the king a majority.” It’s unclear if this would have actually worked as well as d’Haussez said — in his memoirs, the baron noted that it would have been “difficult to give government jobs to members of the left without offending the royalists upon whom [Charles] counted for his basic support.” Regardless, Charles “firmly rejected” this plan.24

One final very intriguing path not taken was a major ministerial shakeup. For all of Charles’s loyalty to Polignac, there was one man in France who combined the ultraroyalist credentials and personal connections to Charles to potentially replace the king’s “dear Jules”: Charles’s former prime minister, Joseph de Villèle.

One final very intriguing path not taken was a major ministerial shakeup. For all of Charles’s loyalty to Polignac, there was one man in France who combined the ultraroyalist credentials and personal connections to Charles to potentially replace the king’s “dear Jules”: Charles’s former prime minister, Joseph de Villèle.

Right: Joseph de Villèle, by Jean Sébastien Rouillard, circa 1820s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Election of 1827 had been driven by widespread opposition to Villèle’s government. But a few months’ experience of Polignac seems to have made some members of the opposition nostalgic for Villèle’s more incrementalist brand of ultraroyalism. The deposed Villèle had been living in his home city of Toulouse, but coincidentally happened to arrive in Paris in March 1830 for the birth of his grandchild. Villèle arrived soon after the Address of the 221 and Charles’s dismissal of parliament, and was immediately swarmed with allies and old friends encouraging him to re-enter the government.25

In accordance with the conventions of the day, Villèle publicly insisted he had no desire to return to government. But this was a polite fiction. As historian Vincent Beach notes, for a man who supposedly had no interest in retaking power, Villèle met with “nearly every individual of importance on the royalist side” during this personal visit to Paris. He found even more support than he might have expected.26

On March 31, 1830, Villèle was met at his home by two deputies — one from the center-right, the other from the center-left. These two men told Villèle that they “represented a majority in the chamber” and had the votes to approve a budget if it were proposed by a ministry led by Villèle and not Polignac. This could have been an off-ramp for France’s political crisis, or at least a way for both sides to stall for time instead of accelerating to a confrontation. Because it’s not like these centrist deputies liked Villèle — they just thought he was less dangerous than Polignac. Villèle recorded in his memoirs that the deputies told him that Polignac’s leadership “is going to lead us into revolution.” And no matter how much they disliked how Charles was governing, these centrists hated the idea of a revolution — hated it so much they were willing to even work with the vile Villèle if it would prevent one.27

But Charles said no.

The king initially greeted Villèle warmly, teased him for his public reticence, and invited him to a royal audience. But when this audience came, Charles just made chit-chat rather than talking politics. Behind the scenes, it seems to have ultimately come down to which man Charles wanted at his side. Polignac was willing to have Villèle join his ministry in a junior role, but not to step aside to see Villèle return as prime minister. Villèle was just as firm about refusing to serve under Polignac. Forced to choose, Charles decided to stick with Polignac and the path of confrontation, rather than bring on Villèle to defuse the crisis. Instead, hearing Villèle out and flattering him seems to have been less serious consideration and more an attempt to mollify him — if Polignac wanted to govern with only ultraroyalist support, he could not afford to do without Villèle’s loyalists in his coalition. And so, after a few weeks of “whirlwind” talks, Joseph de Villèle left Paris for home.28

Saying the quiet part out loud

So that’s what Charles and Polignac didn’t do to change the political game. What they did do was introduce several new elements into the ministry’s electoral toolkit, new ways to appeal to wavering voters.

One was to explicitly enroll the Catholic Church on the government’s behalf. Bishops were requested to send pastoral letters asking their parishioners to vote for government candidates. Not all bishops did so, but some did so enthusiastically. The bishop of Metz in northeastern France, for example, sent a public “pamphlet on the election” to his priests, as well as a secret letter “ordering them to explain to their parishioners which parliamentary candidates were worthy of their blessing.” The archbishop of Paris preached his message from the pulpit at Notre Dame, that the Bourbon throne was “inseparable from the cross” and that Catholics had a “duty to obtain monarchical and religious elections.”29

One was to explicitly enroll the Catholic Church on the government’s behalf. Bishops were requested to send pastoral letters asking their parishioners to vote for government candidates. Not all bishops did so, but some did so enthusiastically. The bishop of Metz in northeastern France, for example, sent a public “pamphlet on the election” to his priests, as well as a secret letter “ordering them to explain to their parishioners which parliamentary candidates were worthy of their blessing.” The archbishop of Paris preached his message from the pulpit at Notre Dame, that the Bourbon throne was “inseparable from the cross” and that Catholics had a “duty to obtain monarchical and religious elections.”29

Right: Hyacinthe-Louis de Quélen, Archbishop of Paris (1821-1839), unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This marked a new level of explicit and open involvement in electoral politics by Catholic officials. It’s not that anyone in the Bourbon Restoration was surprised the Catholic Church leaned royalist. Rather, it was a break in tradition to express these beliefs so bluntly.30

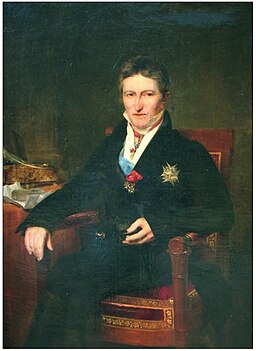

The Church wasn’t the only entity that scandalized people by saying the quiet part loudly during the 1830 election. So did the French monarchy. In past elections, the king’s government had actively meddled to promote friendly candidates, and hadn’t hesitated to invoke the king’s name in doing so. In the election of 1827, for example, one prefect wrote a letter telling government employees that “His majesty desires the re-election of most of the members of the last chamber” and that “all officers of the administration owe the king their full cooperation.”31 But that was indirect (and in at least that instance, not intended for publication). Neither Louis nor Charles had taken open, public electoral positions — until June 1830. That’s when Charles issued a proclamation for nationwide publication, which I’ll quote at length:

To maintain the Constitutional Charter and the institutions it has founded, has been, and always will be, the object of all my efforts. But to attain this aim, I must exercise freely, and have respected, the sacred rights which are the attributes of my crown… The nature of the government would be altered if culpable attacks weakened my prerogatives… Voters, hurry and go to your [electoral] colleges… May you all rally around the same flag! It is your King who is asking you to do this; it is your father who is calling upon you. Do your duty and I’ll do mine.32

This was a big gamble, and an escalation. If his appeal worked, Charles might secure the parliament he wanted. If it failed, “a defeat for his party in the elections would be not merely a defeat for the ministry but a defeat for the crown.”33

Above: Charles X’s proclamation in the June 14, 1830 issue of the Moniteur universel calling on all loyal Frenchmen to vote for his candidates in the upcoming elections for the Chamber of Deputies. Public domain via Diginole.

The 221

But Charles and his bishops were not making these appeals into the void. They were up against what had become a well-honed electoral playbook from the liberal opposition.

Liberals formed local electoral committees under the auspices of the Aide-toi, le ciel t’aidera society I discussed in Episode 31 — the name, you’ll recall, means “God helps those who help themselves.” These committees, coordinating their efforts with national leaders in Paris, recruited candidates, canvassed voters, and helped liberals overcome hostile prefects to get properly registered to vote. In all this, liberals had the advantage of support from the country’s most popular newspapers. Best-selling papers such as Le Constitutionel and the Journal des débats bombarded the Polignac ministry with daily attacks, and printed lengthy voter manuals.34 Against this onslaught, the Polignac ministry relied on a number of smaller papers, and also on the expedient of bribing newspaper editors to run pro-Polignac articles. Prefects had secret slush funds that could be used for all sorts of electioneering expenses, such as the prefect of the Gironde who spent 500 francs in 1830 “for the encouragement of some newspaper articles.”35

Liberals formed local electoral committees under the auspices of the Aide-toi, le ciel t’aidera society I discussed in Episode 31 — the name, you’ll recall, means “God helps those who help themselves.” These committees, coordinating their efforts with national leaders in Paris, recruited candidates, canvassed voters, and helped liberals overcome hostile prefects to get properly registered to vote. In all this, liberals had the advantage of support from the country’s most popular newspapers. Best-selling papers such as Le Constitutionel and the Journal des débats bombarded the Polignac ministry with daily attacks, and printed lengthy voter manuals.34 Against this onslaught, the Polignac ministry relied on a number of smaller papers, and also on the expedient of bribing newspaper editors to run pro-Polignac articles. Prefects had secret slush funds that could be used for all sorts of electioneering expenses, such as the prefect of the Gironde who spent 500 francs in 1830 “for the encouragement of some newspaper articles.”35

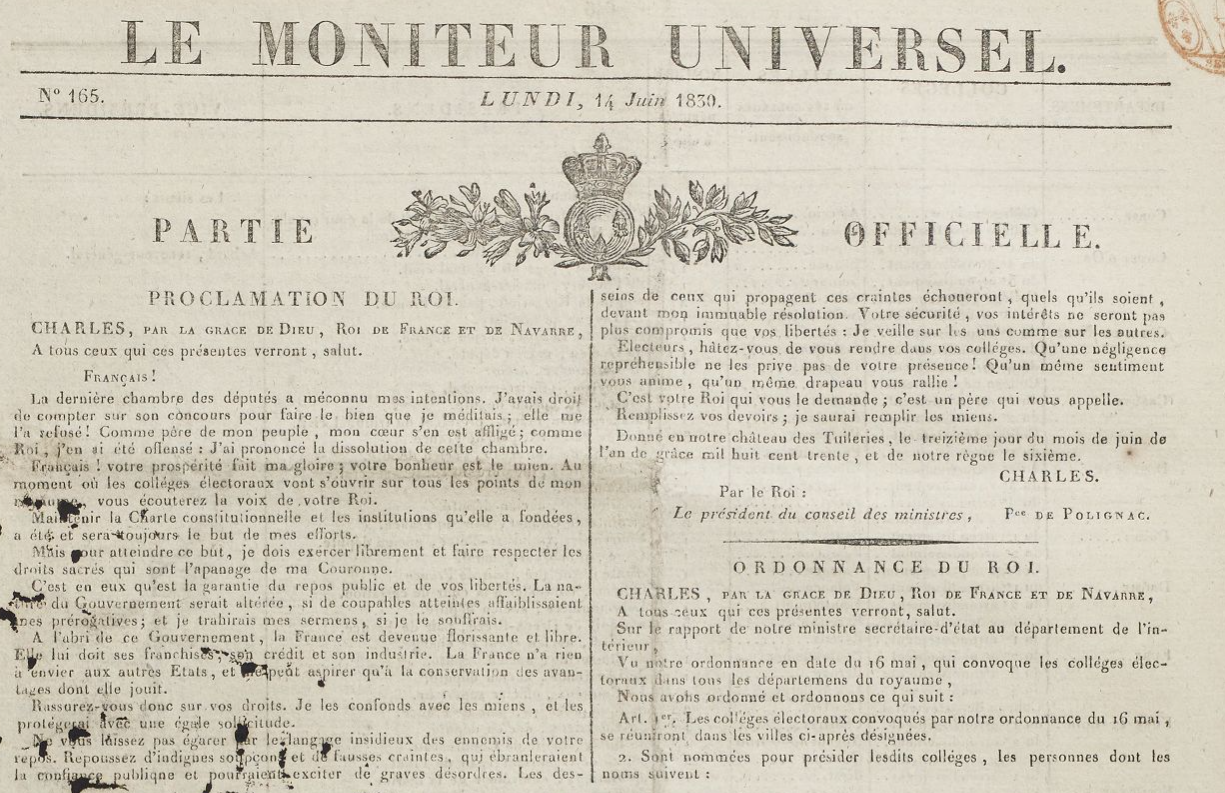

Above: Printed copy of the Address of the 221, March 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The emotional heart of the 1830 campaign were the famous “221” — the majority of deputies who had approved the confrontational address telling Charles that his people were “offended” by Polignac’s ministry, and that “their liberties are threatened.” The opposition saw the 221 as heroes; they organized banquets in their honor and concentrated their efforts on making sure that as many of the 221 as possible got re-elected.36

Ultraroyalists, on the other hand, saw the 221 as literal traitors. The Gazette de France wrote that the 221 had “‘forfeited’ their right to be elected.” The Quotidienne wrote that “anyone who voted for a member of the ‘221’ would be guilty of a felony.”37

There was only one real hitch with both sides’ efforts to elect or defeat the 221: knowing who they were.

See, the French Chamber of Deputies in the Bourbon Restoration did not conduct roll-call votes. Deputies voted by physically walking up to a box in the chamber and dropping a ball in to reflect their vote: a white ball for “yes” and a black ball for “no.” That there were 221 white balls in the box after the vote on the Address is not in doubt. Figuring out which deputies had dropped those 221 white balls requires some detective work.38

This detective work started almost immediately. On April 13, a month after the vote, the Courrier Français newspaper published a “complete list of the ‘221’” and urged their election. So did several other newspapers and pamphlets. But these lists don’t all agree! Historian Sherman Kent’s analysis found 217 men who are reasonably certain to have been among the 221. There are another dozen or so potential members — a situation inflated by the tendency of some men who claimed after the fact that they had been in that august number, and others who said they would have been had they not been absent that day.39

Regardless of this fuzziness, most of the 221 were not in dispute, even at the time. That was perhaps not ideal for the roughly 75 of the 221 who held salaried government positions — including, remarkably, one departmental prefect! Many of these men were purged in the aftermath of their defiant vote, as were other officials who were deemed to be insufficiently loyal. This didn’t go far enough for Ultra newspapers like the Quotidienne, which “demanded a complete purge of the public [functionaries] from the first [gentleman of the royal bedchamber] to the lowest [village mayor].” The actual number of officials dismissed was considerably smaller than these demands, due in part to the resistance of several legalistic government ministers.40

But resistance to Polignac’s plans from inside his government was fading. In May, Charles formally dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, two months after he suspended it. By dissolving the Chamber then, Charles set new elections for late June and early July 1830 — ideally when news of the successful invasion of Algiers was fresh in everyone’s minds. But this also prompted the ministers of finance and justice to resign. Both men were opposed to dissolving the Chamber, and resistant to the idea of Charles taking a forceful response if the opposition won the new elections. Charles and Polignac, who supported dissolution and the forceful response, “welcomed their retirement.” In the resulting ministry shuffle, several new hard-line Ultras were brought into government to replace the departed moderates. That included Ferdinand de Bertier, the founder of the secret Chevaliers de la Foi secret society, and the Comte de Peyronnet, a former minister who was infamous for claiming an 1827 censorship bill was actually a “Law of Justice and Love.”41

But resistance to Polignac’s plans from inside his government was fading. In May, Charles formally dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, two months after he suspended it. By dissolving the Chamber then, Charles set new elections for late June and early July 1830 — ideally when news of the successful invasion of Algiers was fresh in everyone’s minds. But this also prompted the ministers of finance and justice to resign. Both men were opposed to dissolving the Chamber, and resistant to the idea of Charles taking a forceful response if the opposition won the new elections. Charles and Polignac, who supported dissolution and the forceful response, “welcomed their retirement.” In the resulting ministry shuffle, several new hard-line Ultras were brought into government to replace the departed moderates. That included Ferdinand de Bertier, the founder of the secret Chevaliers de la Foi secret society, and the Comte de Peyronnet, a former minister who was infamous for claiming an 1827 censorship bill was actually a “Law of Justice and Love.”41

Above: Pierre-Denis, Comte de Peyronnet. Unknown artist, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The cabinet shuffle was widely seen as producing a more hard-line government, by journalists on both the right and left. The only real difference was many ultraroyalist newspapers cheered this development, adopting the slogan “No more concessions,” while liberal newspapers saw it as a sign of doom. As the Globe wrote: “The Ministry has sounded the [warning bell] of its fate. The counterrevolution is on the march; it is up to the electors to save France.”42

Bad vibes

By now you’re getting a sense of the fevered nature of French politics in the spring and summer of 1830. If anything, I’m underselling things. Almost everyone saw a huge confrontation coming between Charles and the opposition, advancing with the inexorable inevitability of a boulder rolling downhill. Many French politicians recoiled from this prospect and were willing to do unthinkable things — like liberals voting for Villèle — in a desperate attempt to avert it.

Some more radical voices on both sides welcomed the clash. Charles and Polignac were “bombarded” with letters urging Charles to seize unilateral power and sweep away the treasonous deputies.43 The Drapeau Blanc newspaper urged the king to strike “the full blow” quickly, lest it be “too late.”44 The liberal journalist Adolphe Thiers was “growing impatient” for Charles to overstep, and wrote that voters should “dare” the ministry to violate the Charter.45

Driving home the state of unease, France was also beset by a frightening spree of mysterious fires in western France. Between February 18 and July 7, officials counted 178 structure fires in three different departments, with “substantial” property damage and no obvious cause or culprit. Soldiers were dispatched to restore order, and many suspects were interrogated, but no culprit was ever proved. Ultraroyalists and liberals each accused the other of setting the fires for political purposes, with little evidence. The most likely explanation was probably some combination of “aimless protest” amid France’s ongoing economic crisis, and copycat crimes — though one historian did conclude that insurance companies may have set some of the fires to try and sell policies. Regardless, the unsettling series of arsons “added to the general atmosphere of tension and uncertainty.”46

None of these bad vibes were enough to interrupt elite social life, of course. New plays and operas continued to debut throughout these crisis months, including — in February 1830 — a new play by Victor Hugo called Hernani. In it, Hugo discarded the “classical unities” which held that tragedies had to take place in a single place in a single day; he gleefully mashed up humor and tragedy in ways that seemed grotesque; his language was “disgracefully intimate and idiomatic.”47

None of these bad vibes were enough to interrupt elite social life, of course. New plays and operas continued to debut throughout these crisis months, including — in February 1830 — a new play by Victor Hugo called Hernani. In it, Hugo discarded the “classical unities” which held that tragedies had to take place in a single place in a single day; he gleefully mashed up humor and tragedy in ways that seemed grotesque; his language was “disgracefully intimate and idiomatic.”47

Left: Victor Hugo, by Achille Devéria, 1829. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A year before, the Martignac ministry had banned another of Hugo’s plays for allegedly including veiled insults of Charles. Hugo appealed directly to the king, who granted Hugo an audience and claimed to be an admirer. When the royal decision came down, the play stayed banned, but Charles offered compensation: the huge sum of 4,000 francs per year as a government pension, and a post as an advisor on the royal Council of State. Hugo, with his mastery of words and flair for the dramatic, turned down the offer with the statement: “I had asked for my play to be performed, and I ask for nothing else.”48

Now Charles had a second chance. Outraged members of the French Academy urged Charles to ban Hernani. But when it was a question of taste instead of politics, Charles was more generous. The old king rejected the censorship request with a self-deprecating quip about how he was merely another audience member. The play debuted on February 25, with famous confrontations between pro- and anti-Hugo factions in the audience over its 39-performance run.49 Despite everything else going on — Charles addressed the Chambers one week later! — historians note that Hugo’s controversial play was what dominated conversation: “The salons talked of little else.”50

Dancing on a volcano

Another famous mix of high class and vulgarity happened three months later. The occasion was not a revelatory drama but a dramatic revel.

Another famous mix of high class and vulgarity happened three months later. The occasion was not a revelatory drama but a dramatic revel.

Left: King Francis I of the Two Sicilies, by Vicente López Portaña, 1829. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In May 1830, King Francis I of the Two Sicilies visited Paris on his way home to Naples, his capital at the foot of the volcano Mount Vesuvius. The occasion was not merely state business but also family affairs: Francis’s sister was Marie-Amélie, the Duchesse d’Orléans, while his daughter was Marie-Caroline, the Duchesse de Berry. (For those who’ve gotten a little lost with the tangled Bourbon family trees, his sister was married to Charles’s cousin, the Duc d’Orléans. His daughter had been married to Charles’s son, the Duc de Berry, until Berry’s 1820 assassination, and was the mother of the king’s grandson and eventual heir, the Comte de Chambord. Check out Episode 15 for more backstory there.)

During this visit, the Duc d’Orléans paid tribute to his brother-in-law by hosting a truly massive party for him at his Parisian palace, the Palais-Royal. The duke had a few goals. One was to simply show off his vast wealth and importance: Louis-Philippe was perhaps the richest man in the realm, and he used his money carefully to burnish his public image. So a glittering gala it was: 400 laborers worked for weeks to prepare the Palais-Royal for up to 3,000 distinguished guests. As a side benefit, the duke hoped the splendor might help convince Francis to agree to a royal marriage between Francis’s son and one of Louis-Philippe’s daughters.51

Charles himself graced the party with his attendance. One source claims he was “welcomed by cries of ‘vive le roi!’ in sufficient number to convince him he was still loved,” though other sources say the king had a more muted reception. Regardless, Charles told Orléans it was “the finest ball he had seen.”52

Charles himself graced the party with his attendance. One source claims he was “welcomed by cries of ‘vive le roi!’ in sufficient number to convince him he was still loved,” though other sources say the king had a more muted reception. Regardless, Charles told Orléans it was “the finest ball he had seen.”52

Right: Portrait of Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, by Nicolas Jacques, 1827. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Spectators began queuing up in the morning for a look at the glittering arrivals. Eventually the streets became so choked that it took carriages an hour and a half to travel between the Place du Carrousel to the Palais-Royal, a five-minute walk in normal times. Some spectators were dressed to the nines themselves; others were less distinguished sorts. Late in the evening, some of the crowd became unruly, breaking windows and garden chairs. Guards restored order without any fatalities, but the guests were struck by their brush with danger. One attendee famously quipped to Louis-Philippe that he had given “a true Neapolitan party: We are dancing on a volcano.”53

Algiers, part 2

While all this social drama and political agitation was happening, let’s not forget: there was a war going on!

The huge invasion force Baron d’Haussez had gathered at Toulon was ready by May. Polignac had cleared the diplomatic obstacles. Now all that remained was to give the order. Or so the government assumed, anyway.

Everything was operating on a very tight timetable. The May 16 dissolution of parliament had been timed to occur on the same day that War Minister Louis Auguste de Bourmont certified the Algiers expedition was ready to depart. The late-June elections were scheduled to coincide with when the cabinet expected to hear news of France’s successful conquest of Algiers. The hope was that the resulting patriotic fervor would provide the final boost to pro-ministry candidates in the elections.54

On May 18, Charles formally appointed the expedition’s commander: his war minister, Bourmont. Bourmont, who was also named a Marshal of France at the same time, was seen as the most loyal among France’s senior generals. He was also personally eager to claim a triumph on the field of battle, given that Bourmont’s last campaign had been Waterloo, which infamously ended with Bourmont defecting from Napoleon to the Allies a few days before the battle. Good for his political career, but bad for his reputation; a glorious victory was just what the doctor ordered for the new marshal.55

On May 18, Charles formally appointed the expedition’s commander: his war minister, Bourmont. Bourmont, who was also named a Marshal of France at the same time, was seen as the most loyal among France’s senior generals. He was also personally eager to claim a triumph on the field of battle, given that Bourmont’s last campaign had been Waterloo, which infamously ended with Bourmont defecting from Napoleon to the Allies a few days before the battle. Good for his political career, but bad for his reputation; a glorious victory was just what the doctor ordered for the new marshal.55

Left: Admiral Guy-Victor Duperré, by Eugène Charpentier, unknown date. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But the delicate timetable was swiftly in danger. Fleets in 1830 were dependent on the winds, and the first favorable wind didn’t arrive until May 25 – a week lost. The voyage across the Mediterranean to North Africa took just two days. But on arrival, Bourmont’s desire for haste was overruled by the senior admiral — Guy-Victor Duperré, the cautious fellow who had insisted it would take a year to prepare an expedition of this scale. Duperré thought the winds made landing dangerous, so ordered the fleet to retreat back to the island of Majorca, to wait for better winds.56

There the expedition passed 10 tedious days. Finally, on June 10, when the winds improved but Duperré still hesitated, Bourmont pulled rank and ordered the admiral to set sail whether he wanted to or not.57 The first French troops finally waded ashore on June 14, nearly a month after the expedition was formally approved. With travel delays, news of the landing reached Paris on June 18, just five days before the first electoral colleges were to meet.58

The landing, at least, came off well despite the delays. Amphibious assaults are risky at the best of times, but the French met “only very weak resistance” by irregular fighters, and were able to land their full army mostly unimpeded. Their next test came on June 19, when the Algerians attacked in force. Bourmont was outnumbered, with some 37,000 men against as many as 60,000 Algerians. The Dey of Algiers, Hussein, had used his extra weeks well, and raised fighters from across his domain, including regular soldiers, tribal levies, and volunteers to fight off the Christian invaders. But the French army was better trained and better equipped. A ferocious charge by the Algerian cavalry led to serious hand-to-hand fighting in blazing heat, but the French lines held — and then counterattacked. The French advance overran the Algerian camp, and ended the day in command of the field.59

At this point Bourmont was forced to pause for artillery and supplies to be unloaded. In particular the giant siege guns the French had brought with them were stuck back in Majorca — another casualty of Admiral Duperré’s abundant caution.60

When the French finally got moving again toward Algiers, it was June 24 — one day after the first French electoral colleges had voted. The military campaign was on a path to victory, but it would come too late to affect the election campaign.61

“Attack on Algiers from the sea, June 29, 1830,” by Théodore Gudin, 1831. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1830 landslide

As Duperré’s fleet bided its time, the liberal opposition back home had become increasingly optimistic about the upcoming election. The mood of France’s wealthy elite was firmly anti-Polignac, and pressure from bishops and the king himself had failed to change that.62

The one real wild card was the Algerian expedition. Liberals generally saw the invasion as a wag-the-dog political ploy, but they also were wary of being seen as unpatriotic or opposing the troops. One tactic was to attack Polignac for sending soldiers to Algiers instead of to retake France’s lost departments along the Rhine River. One pamphlet argued that deploying “forces merely on the Rhine” would have been cheaper than sending them to Africa, and that to “regain our provinces and give us back a part of our natural borders” was a more worthy goal.63 Others tried to draw a distinction between “the man who commands this expedition against the will of all France” and “the ardent wishes of men impassioned for national glory.”64

Whether it was liberals successfully nullifying this political trap with careful rhetoric, the incomplete nature of Bourmont’s advance, or simply that hatred for Polignac overwhelmed everything else, the elections of 1830 were a slow-motion landslide for the opposition. Polignac tried a last-minute maneuver by delaying the electoral colleges in 20 departments by several weeks. This was ostensibly due to the need to resolve ongoing disputes about voter eligibility, but these just happened to be 20 departments where opposition forces were particularly strong. This way more royalist areas could vote first and create momentum for both the second round of “double vote” electoral colleges and for the delayed departments themselves — as opposed to the opposition getting that momentum.65

That was the plan, anyway. But when these “royalist” electoral colleges voted, opposition candidates had won 140 seats out of 195, more than 70 percent! At that point the writing was on the wall: when the delayed opposition departments voted, they would only confirm the opposition’s lead — whatever the news from Algeria. The ultraroyalist Gazette de France newspaper published a sad lament: “Our troops are victorious in Africa, and the royalists go down to defeat in the electoral battle.” The more extreme Drapeau Blanc was drew a darker conclusion: that “the electors have voted for the guillotine.”66

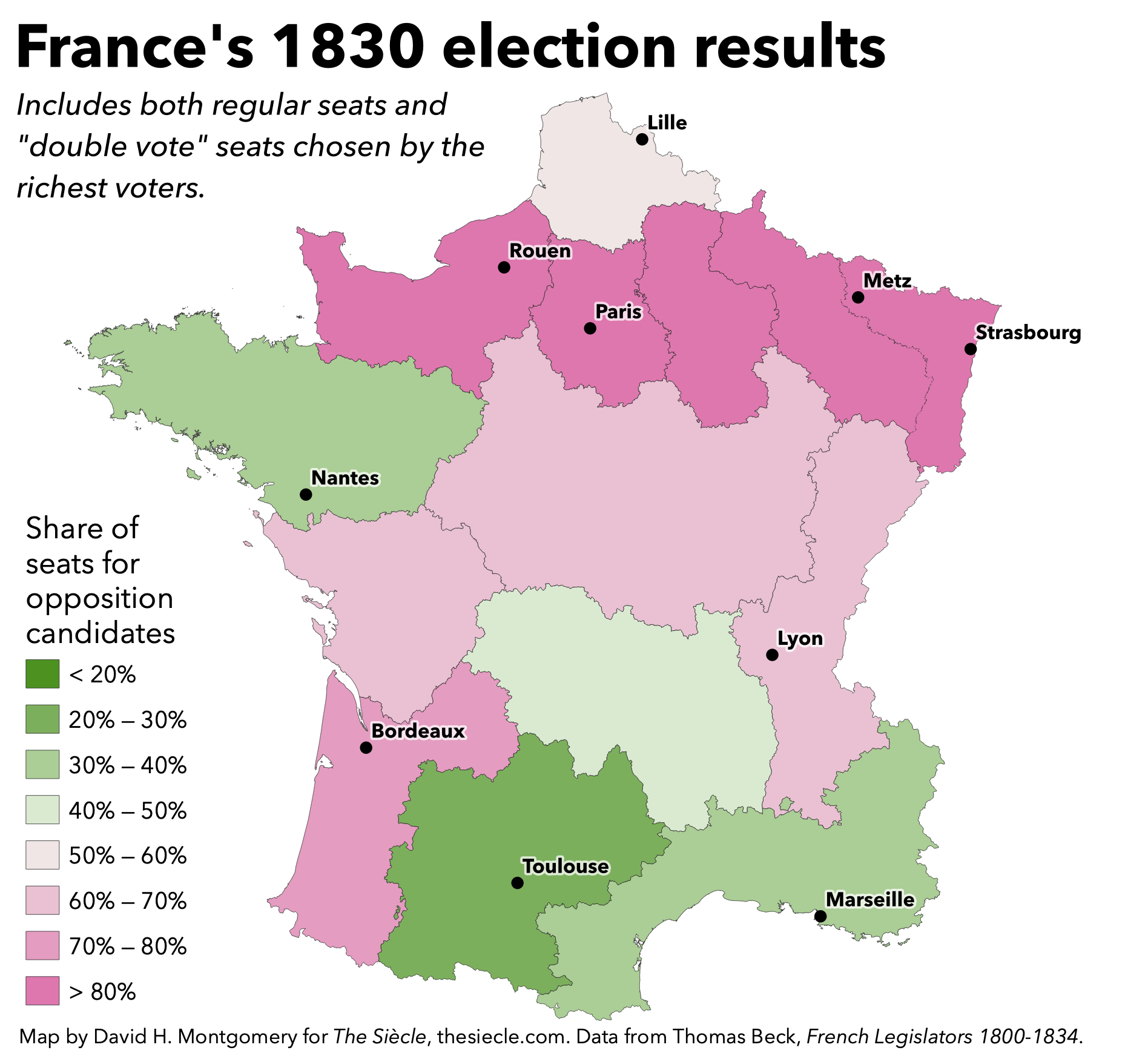

When the final votes were counted in late July, including the delayed departments and the special “double vote” electoral colleges composed of the richest voters, opposition deputies had grown their majority from 221 to around 274 out of 428, or 64 percent. Of the famous 221, 202 got re-elected.67

The decision

The only consolation for Charles was the continued good news from Algeria. Bourmont’s army marched from its landing site to the outskirts of Algiers by July 4. There they faced their final obstacle: the imposing fortress of Borj Mawlay Hasan, which the French called “Fort l’Empereur “ because it had famously withstood an assault in 1541 by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. But nearly 300 years had seen some major advancements in artillery technology. After just a few hours of devastating French bombardment, the defenders abandoned their positions. The city of Algiers now stood at Bourmont’s mercy.68

Explosion of the “Fort l’Empereur” on July 4, 1830, by Martinet/Reville, 1838. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Though some Algerian leaders wanted the Dey to keep fighting and call for a mass popular uprising, the city’s merchant elite was ready for peace. With his support collapsing, Hussein surrendered and sailed into exile. Bourmont proudly declared that “Twenty days were all that were required for the destruction of a state whose existence had harassed Europe for over three centuries.” As it happened, France’s conquest of Algeria itself was far from over. But that’s a subject for future episodes. On July 5, 1830, the white Bourbon flag was hoisted over the city of Algiers, and the French helped themselves to the Dey’s massive treasury. Even despite “ill-concealed looting” by French officers, the French state still received well over 40 million francs in loot — enough to cover the cost of the invasion and then some. France had suffered 415 soldiers killed and 2,160 wounded, less than 7 percent of the invasion force.69

France celebrated the victory, but it didn’t make anyone forget the political turmoil — on either side. Adolphe Thiers wrote on July 21 that the government’s “‘violation of the laws’ would occur within the month.” The Archbishop of Paris, leading a celebratory mass for the victory at Notre Dame, assured Charles “the protection of Mary, Mother of God,” and prayed to the king: “May you soon return to thank the Lord for other victories no less sweet and no less brilliant.”70

Some moderate liberals were still trying desperately to head off the confrontation that both Thiers and the archbishop saw as imminent. Deputies offered a discreet olive branch: The king could preserve his dignity, even after this defeat, by making just token concessions. As Sauvigny describes it, “they were even ready to accept almost any ministry as long as there was a new one.” Some even made overtures to Polignac himself, offering to keep him in a reshuffled government. Anything was on the table to prevent an apocalyptic confrontation that threatened to unleash revolutionary terror.71

But it was too late for that. Charles was committed. On July 25, 1830, King Charles X of France and his council of ministers had agreed that the king would override the elections and seize emergency power for himself.72 The long-awaited battle was at hand, and with it, the fate of the Bourbon Restoration.

The Siècle is a proud part of the Evergreen Podcasts network. Find out how you can support the show by visiting thesiecle.com/support. And don’t forget to submit your questions for the show’s fifth birthday Q&A episode by emailing david@thesiecle.com!

When we next pick up our main narrative, we’ll look at Charles’s fateful decision to assert royal authority over his truculent subjects. Join me next time for Episode 39: The Four Ordinances.

-

Rory Muir, Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace, 1814-1852 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015), 359. ↩

-

Muir, Wellington, 359. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 433. ↩

-

Munro Price, “‘Our aim is the Rhine frontier’: the emergence of a French forward policy, 1815-1830,” French History, Vol. 33, No. 1, 25. ↩

-

Price, “‘Our aim is the Rhine frontier’,” 1. ↩

-

Price, “‘Our aim is the Rhine frontier’,” 4-19. Lauren Henry, “‘Algeria Is the Border of the Rhine’: French Continental Ambitions and the Conquest of Algeria, 1827-1848,” paper presented at Identity, Inclusion, and Exclusion in the Francophone World: The 67th Annual Meeting of the Society for French Historical Studies, Charlotte, N.C., March 24-26, 2022., 6. ↩

-

G.W.T. Omond, “The Question of the Netherlands in 1829-1830,” in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 2 (1919), 160. Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 274. ↩

-

Price, “‘Our aim is the Rhine frontier’,” 23. ↩

-

Muir, Wellington, 360. ↩

-

Mark Mazower, The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (New York: Penguin Press, 2021), 433-4. Muir, Wellington, 361. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 435. ↩

-

Henry, “‘Algeria Is the Border of the Rhine’,” 1, 7. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 435-6. Henry, “‘Algeria Is the Border of the Rhine’,” 6. Charles-Robert Ageron, Modern Algeria: A History from 1830 to the Present, ed. and trans. Michael Brett (Trenton: Africa World Press, [1991] 2016), 5. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 436. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 436-7. ↩

-

Muir, Wellington, 366-77. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 436. ↩

-

J.E. Swain, “The Occupation of Algiers in 1830: A Study in Anglo-French Diplomacy,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Sept. 1933), 361. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 436-7. ↩

-

Swain, “The Occupation of Algiers in 1830,” 462-4. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 437. ↩

-

See Beach, Charles X, 323; and Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 134-5. The issue was not whether Polignac and Charles intended to abide by the Charter, but what they meant by abiding by the Charter — interpretations that different from many other leading French figures. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 269-70. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 429. Beach, Charles X, 321-2. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 316. The liberal press covered Villèle’s visit and its obvious political implications. As historian Daniel Rader notes, “The opposition always paid Villèle the compliment of taking whatever he did seriously; while an air of incredulity touched with derision appeared in much of its discussion of Polignac.” Daniel L. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827-30 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 188. ↩

-

Pamela Pilbeam, The 1830 Revolution in France (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 33-4. ↩

-

Pilbeam, The 1830 Revolution in France, 34. ↩

-

Sherman Kent, The Election of 1827 in France (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1975), 138. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 341. ↩

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 31. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 32. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 32. Pilbeam, The 1830 Revolution in France, 34. Some of the more radical members of the opposition balked at this plan, however. Since many of the 221 were moderates or even right-of-center, some journalists of republican sentiments “urged the reelection of only those well to the Left.” But “their collective voice was modest.” Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 190. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 190, 202. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 205. ↩

-

Kent, The Election of 1827 in France, 205-6. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 319, 335-6. (No, Christine, I do not know the identity of this disloyal prefect.) ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 201-2. Peyronnet had been Villèle’s justice minister, though by 1830 he was no longer close to Villèle and his appointment was seen as a defeat for Villèle’s faction. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 200, 203. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 202. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 207. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 318-9. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 198-9. ↩

-

Graham Robb, Victor Hugo: A Biography (New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 145. ↩

-

Robb, Victor Hugo, 144. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 282. Robb, Victor Hugo 148-53. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 234. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 234-5. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 326-7. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 205-6. Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 234-5. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 235. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 206. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 437-8. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 437-8. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438. Beach, Charles X, 334. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 35. ↩

-

James McDougall, A History of Algeria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 52. Ahmed Karim Labeche, Côte Ouest d’Alger (self-published, 2016), 51-55. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 209. ↩

-

Henry, “‘Algeria Is the Border of the Rhine,’” 7. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 197-8. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 338. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 431. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 212. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 431. Beach, Charles X, 338-9. ↩

-

McDougall, A History of Algeria, 11, 52. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438. ↩

-

McDougall, A History of Algeria, 52. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 438-9. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 218. Beach, Charles X, 341-2. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 431. ↩