Episode 34: Polignac

This is The Siècle, Episode 34: Polignac.

On Aug. 8, 1829, a new French ministry was appointed. This made a lot of people very angry and has been widely regarded as a bad move.

The new ministry was headed by — well, by no one, exactly, but we’ll get to that. What’s important is that one of the newly appointed ministers was a man named Jules de Polignac. Polignac had most recently been France’s ambassador in London, but he had two far more important qualities as far as the French were concerned: he was a close personal friend of King Charles X, and he was one of the country’s most reactionary ultraroyalists.

Polignac’s mere presence in a French government would have represented a sharp turn to the right in any situation. But it was an especially drastic turn since the outgoing ministry had been a relatively centrist affair, led by the Vicomte de Martignac.

In August 1829, in effect, Charles announced he was done with trying to compromise with a left-leaning Chamber of Deputies. Instead he was declaring political war.

Or at least, that’s how most observers at the time saw it. The reality, as you’ll see, is a little bit more nuanced than that. But even with that caveat, as we pick up our narrative in August 1829, French politics are threatening to boil over.

The story so far

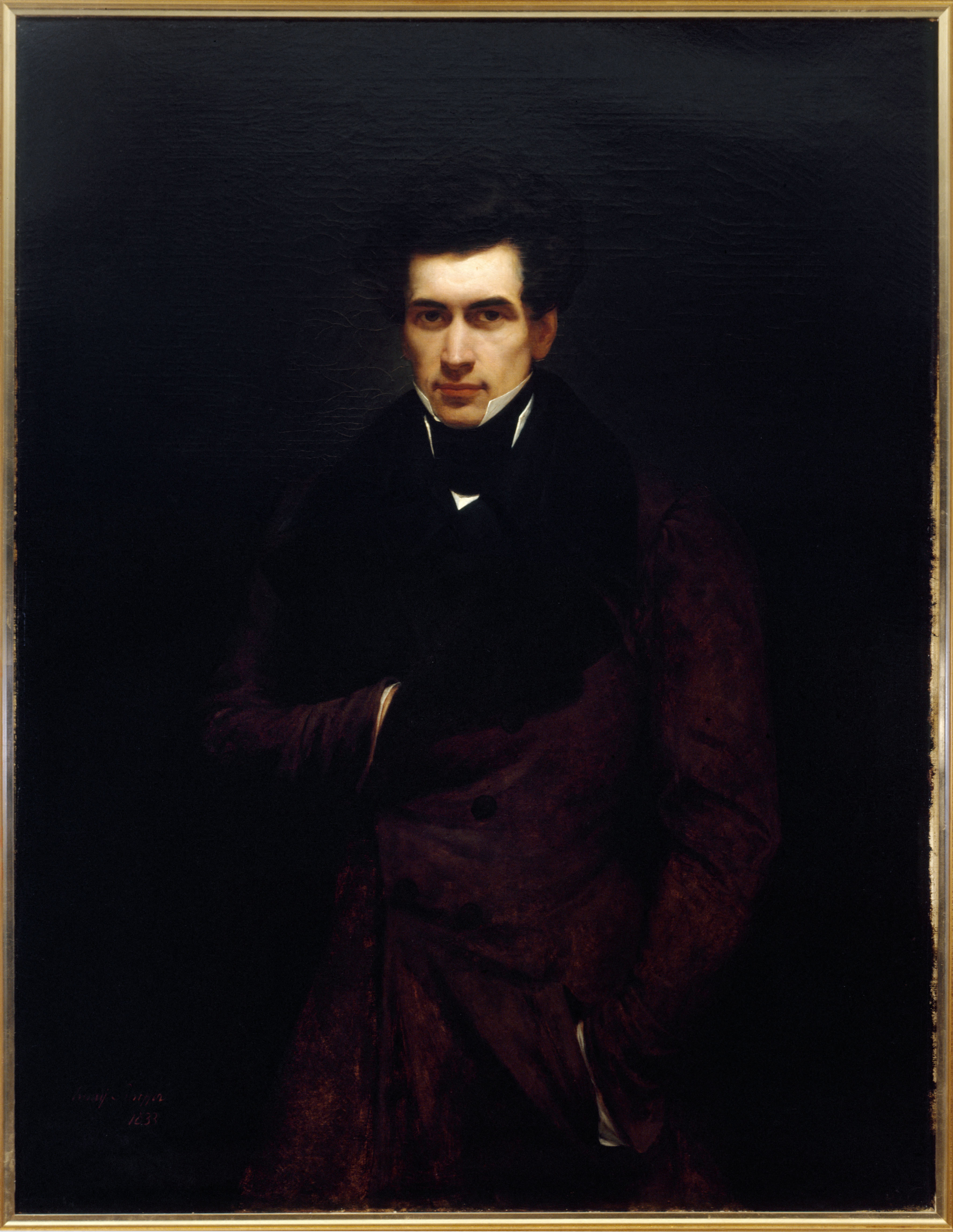

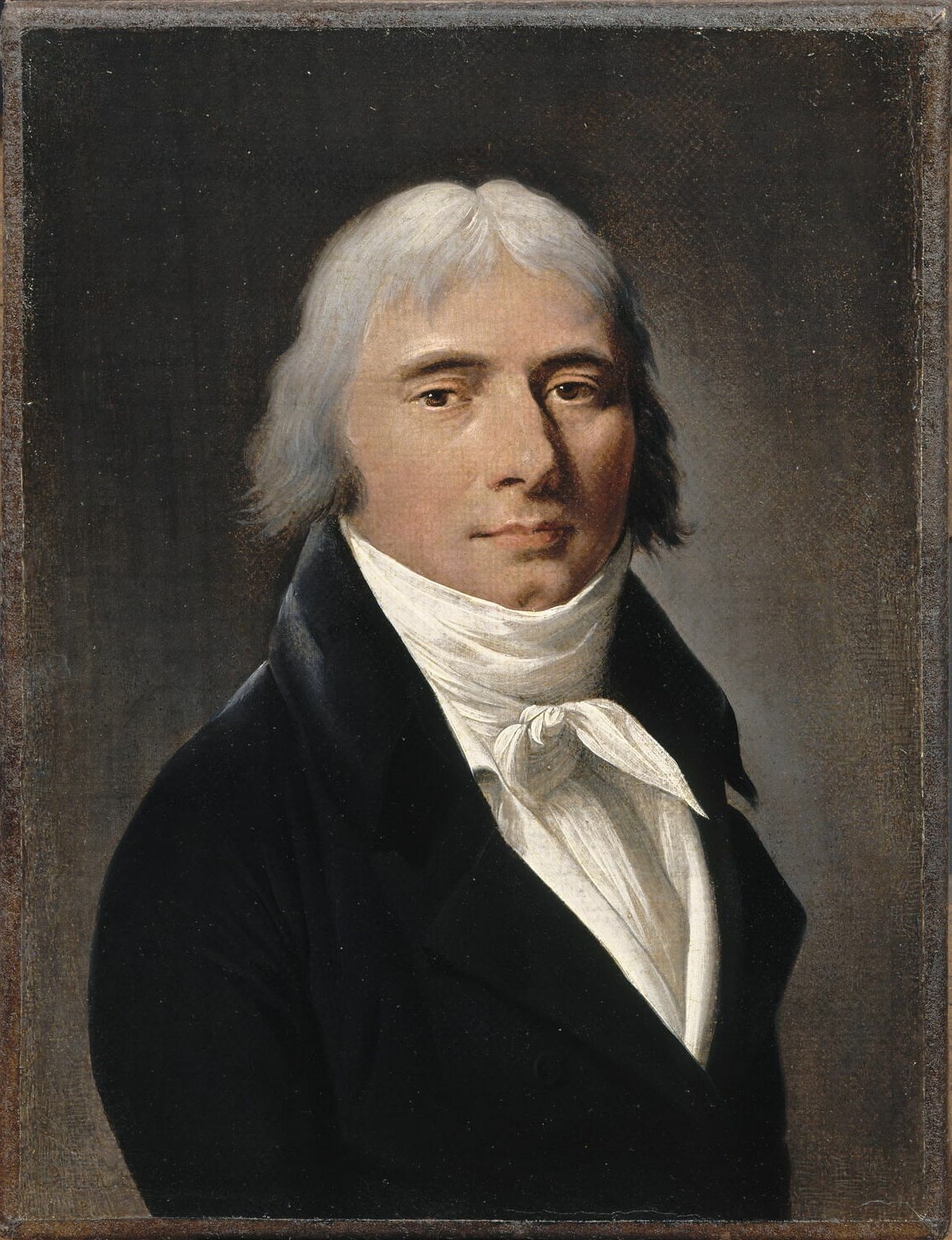

Below: Jules de Polignac, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Let’s step back a bit and start with a quick refresher. The immediate background for the Aug. 8 ministry was France’s Election of 1827, when opposition candidates surprised everyone by gaining scores of seats in France’s Chamber of Deputies. I covered that in Episode 31. The resulting body was fragmented with no clear majority, but a strong block of liberals and a pivotal group of center-right royalists. This forced Charles to ditch his ultraroyalist prime minister Joseph de Villèle, and very reluctantly appoint a more moderate ministry led by Martignac.

Let’s step back a bit and start with a quick refresher. The immediate background for the Aug. 8 ministry was France’s Election of 1827, when opposition candidates surprised everyone by gaining scores of seats in France’s Chamber of Deputies. I covered that in Episode 31. The resulting body was fragmented with no clear majority, but a strong block of liberals and a pivotal group of center-right royalists. This forced Charles to ditch his ultraroyalist prime minister Joseph de Villèle, and very reluctantly appoint a more moderate ministry led by Martignac.

But as I covered in Episode 33, Charles chafed under the compromises Martignac kept asking him to make to get bills through the Chamber of Deputies. So he worked behind the scenes to try to line up a replacement ministry that was more in line with his own ultraroyalist beliefs — and ideally one featuring the man he called “my dear Jules.”

The only problem was very few other people in French politics wanted Jules de Polignac running a ministry. That included liberals who feared Polignac’s politics, to be sure, but also dedicated ultraroyalists like Villèle, who saw Polignac as a rival for his own influence with Charles.1 So Charles had to leave Polignac on the outside for years after he took the throne in 1824.

In Episode 33, we took Martignac’s ministry through the spring of 1829, when Martignac failed to pass a local government reform bill through the divided Chamber of Deputies. As I noted then, Charles didn’t fire Martignac on the spot, but he did announce a change in strategy: “There is no way to come to terms with these people,” Charles told Martignac about liberals. “It is time to stop them.”2

As it happened, Charles let Martignac linger around until the end of the legislative session — July 30, 1829.3 But behind the scenes, the king was lining up Martignac’s replacement. His agent in this was Ferdinand de Bertier, who you might remember from Episode 32 as the founder of the Knights of the Faith, a Catholic secret society. A veteran conspirator, Bertier sounded out various ultraroyalist politicians about joining a ministry, then snuck in to Charles’ private chambers to brief the king without tipping off Martignac.4

The ministry forms

On Aug. 6, with a ministry finally lined up, the news began to leak. Martignac confronted the king about the rumors, and returned to his ministers grim-faced. Most of them then rushed to try and persuade Charles to change his mind, but the king was set. Only the well-regarded finance minister, Antoine Roy, got a friendlier reception — Charles asked him to stick around in the new government. Roy replied that he would only stick around if Martignac stayed, too. “But my ministry is decided,” the king replied. And so was Roy. He refused a final time, and was affectionately dismissed.5

On Aug. 9, the official government newspaper, the Moniteur, announced the new government. The very first item announced that Polignac would be France’s new foreign minister. But he wasn’t the only controversial name gracing the front page that day.

Below: François-Régis de La Bourdonnaye, by J.D. Dallet, before 1839. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Another was the new interior minister, the Comte de La Bourdonnaye — a recurring character here on The Siècle who had infamously said the only way to root out liberals and Bonapartists was “irons, executioners and torture.”6 La Bourdonnaye had led the so-called “counter-opposition,” the group of parliamentary ultraroyalists who opposed Joseph de Villèle’s ultraroyalist ministry for being insufficiently pure. La Bourdonnaye shared that feeling with Polignac, but their similar far-right politics hid some massively important differences. For one thing, La Bourdonnaye came from a somewhat secular strain of ultraroyalism, more devoted to the throne than the altar, while Polignac was an ostentatiously devout Catholic.7 When he was initially sounded out to join the government, La Bourdonnaye’s objection was that “the proposed council might be called a ministry of the Congregation,” the alleged Catholic secret society that was widely believed to be manipulating events behind the scenes.8

Another was the new interior minister, the Comte de La Bourdonnaye — a recurring character here on The Siècle who had infamously said the only way to root out liberals and Bonapartists was “irons, executioners and torture.”6 La Bourdonnaye had led the so-called “counter-opposition,” the group of parliamentary ultraroyalists who opposed Joseph de Villèle’s ultraroyalist ministry for being insufficiently pure. La Bourdonnaye shared that feeling with Polignac, but their similar far-right politics hid some massively important differences. For one thing, La Bourdonnaye came from a somewhat secular strain of ultraroyalism, more devoted to the throne than the altar, while Polignac was an ostentatiously devout Catholic.7 When he was initially sounded out to join the government, La Bourdonnaye’s objection was that “the proposed council might be called a ministry of the Congregation,” the alleged Catholic secret society that was widely believed to be manipulating events behind the scenes.8

For another, my sources are fairly unanimous that La Bourdonnaye was — to be precise — a huge asshole. He was noted for using the most inflammatory language in his speeches. One contemporary described him as having “eyebrows arched in a perpetual frown, a mouth habitually twisted by a laugh more nasty than evil,” and “jerky, inattentive, disdainful conversation, which livens up only when it becomes ungracious and annoying.”9 Chateaubriand said La Bourdonnaye reminded him of “an irritated bat,” and said he was “certainly the most disagreeable personage that ever lived.”10 Polignac knew that the Ultras needed to form a united front if they wanted to succeed, which meant working with La Bourdonnaye. But the two very much did not get along. The Viscount de La Rochefoucauld, an ardent royalist and Charles’s longtime aide-de-camp,11 wrote a pleading letter to the king urging his friend and boss to see sense: “As far as unity is concerned, Polignac and La Bourdonnaye will never work together,” Rochefoucauld wrote. “How is it that I am obliged to remind the king, who knows them as well as I do, of the principal traits of these two honorable men… [T]hey will not be united for six months.”12 Just how long this partnership will actually last we’ll see, but at least at the start, the two men set aside their differences to pursue their shared goal of steering France in an ultraroyalist direction.

Historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny notes that while Polignac’s appointment had been expected for years, La Bourdonnaye was more unexpected and shocking. So too was the appointment of General Louis Auguste de Bourmont as minister of war.13 Bourmont had a capable military record, but he was best known for joining Napoleon during the Hundred Days, only to defect to the Allies three days before the Battle of Waterloo. As a result of a series of such defections, “no party completely trusted the general.” Opposition papers dubbed him “Judas Bourmont.” The general owed his appointment to Charles’s son and heir, the Duc d’Angoulême, who believed Bourmont’s history meant he could be relied upon to defend the regime. “Bourmont will mount a horse with me, if this step becomes necessary,” Angoulême said.14

Historian Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny notes that while Polignac’s appointment had been expected for years, La Bourdonnaye was more unexpected and shocking. So too was the appointment of General Louis Auguste de Bourmont as minister of war.13 Bourmont had a capable military record, but he was best known for joining Napoleon during the Hundred Days, only to defect to the Allies three days before the Battle of Waterloo. As a result of a series of such defections, “no party completely trusted the general.” Opposition papers dubbed him “Judas Bourmont.” The general owed his appointment to Charles’s son and heir, the Duc d’Angoulême, who believed Bourmont’s history meant he could be relied upon to defend the regime. “Bourmont will mount a horse with me, if this step becomes necessary,” Angoulême said.14

Left: General Louis Auguste de Bourmont, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The rest of the new ministry were mostly men of the far right. This was not entirely intentional. Charles had wanted a more right-wing ministry than Martignac’s, to be sure, but a host of relatively moderate figures like Comte Roy refused to serve alongside Polignac and La Bourdonnaye. The Russian ambassador quipped that where politicians once struggled to become ministers, now the king was struggling to find anyone willing to accept an appointment.15 One such refusal came from Admiral Henri de Rigny, who had commanded the victorious French forces at the Battle of Navarino Bay a few years before.16 The official government newspaper, the Moniteur, published an official announcement on August 9 that the war hero had been named Minister of the Navy. There was only one catch: Rigny hadn’t agreed to take the job. After a few days, he formally declined, driven by both his centrist politics and his disgust for Bourmont the deserter.17

The most stunning example of this outreach to moderates, though, has to be the meeting Polignac had with Élie Decazes. You’ll recall Decazes as the moderate prime minister under Louis XVIII, last seen being hounded out of office by ultraroyalists after the 1820 assassination of the Duc de Berry.18 Now a member of the Chamber of Peers, Decazes was flattered when Polignac asked him for advice — until Polignac casually mentioned La Bourdonnaye’s role in the ministry. “Why didn’t you tell me about La Bourdonnaye right away?” Decazes asked in exasperation. “We would not have spent two hours in vain.” Polignac asked Decazes to join his ministry in the spirit of a unity government,19 but Decazes refused to be a token moderate granting Polignac political cover.20

The most stunning example of this outreach to moderates, though, has to be the meeting Polignac had with Élie Decazes. You’ll recall Decazes as the moderate prime minister under Louis XVIII, last seen being hounded out of office by ultraroyalists after the 1820 assassination of the Duc de Berry.18 Now a member of the Chamber of Peers, Decazes was flattered when Polignac asked him for advice — until Polignac casually mentioned La Bourdonnaye’s role in the ministry. “Why didn’t you tell me about La Bourdonnaye right away?” Decazes asked in exasperation. “We would not have spent two hours in vain.” Polignac asked Decazes to join his ministry in the spirit of a unity government,19 but Decazes refused to be a token moderate granting Polignac political cover.20

Left: Élie Decazes, by by François-Séraphin Delpech after an 1828 portrait by Louis Dupré. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Polignac agenda

So what exactly did Charles, Polignac and the rest of this far-right ministry want to do with their power? There was a widespread belief at the time that the plan was a coup d’état, to overthrow the Charter and allow Charles X to rule by decree.

For example, the Journal des Débats, an opposition newspaper, responded to news of the ministry by asking how the Ultra ministers intended to govern. “Are they expecting support from the army?” the paper asked. “Are they going to destroy the Charter… [?]”21

On the other side of the aisle, Ultra newspapers generally avoided the word “coup” and mocked liberal papers as hysterical for predicting one. But without using the word, they tended to demand the King take “decisive and immediate action against the opposition” using emergency powers. For example, the far-right Drapeau Blanc wrote in December that “if the ministers have the majority, they will save the throne with it; if they do not have it, they will save it without it.”22

Charles and his new ministers certainly seem to have been considering a coup, too. But the available evidence is clear that they were not planning one. Even before Martignac fell, Charles, Polignac and La Bourdonnaye met and agreed that “the Charter would be respected, but that a search be made for legal methods to strengthen royal authority.” Now, that language may not be terribly assuring, but it’s also not “send in the troops to disburse the Chamber of Deputies at gunpoint,” either. In September 1829, Polignac wrote a memo lamenting the current state of affairs and hoping “for us to return some day to a system which incorporates aristocratic principles…”23 But a vague hope is not a concrete plan of action.

Charles and his new ministers certainly seem to have been considering a coup, too. But the available evidence is clear that they were not planning one. Even before Martignac fell, Charles, Polignac and La Bourdonnaye met and agreed that “the Charter would be respected, but that a search be made for legal methods to strengthen royal authority.” Now, that language may not be terribly assuring, but it’s also not “send in the troops to disburse the Chamber of Deputies at gunpoint,” either. In September 1829, Polignac wrote a memo lamenting the current state of affairs and hoping “for us to return some day to a system which incorporates aristocratic principles…”23 But a vague hope is not a concrete plan of action.

Above: Jules de Polignac, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

If Polignac still hoped to achieve his agenda by legal means, what precisely was that agenda? He was a far-right ultraroyalist who had initially refused to take an oath to the Charter, and went to his grave believing that “societies governed by charters will be unhappy and unstable.” Instead, he said that society’s truest foundations were “fear and love of God,” that popular sovereignty was impossible, and that “inequality has always existed and will always exist.” He believed “the monarchial principle” needed to play “a preponderant role” in French government, in contrast to the influence of the aristocracy or the people, though he wanted to increase the power of the clergy. He wanted to “[close] the door of the Chamber of Deputies to mediocre men driven by turbulent and revolutionary passions.”24

But that’s all pretty vague and theoretical. Polignac’s immediate goals were more concrete — and more familiar. Back in Episode 15, I covered France’s political crisis following the 1820 assassination of the Duc de Berry, which culminated in the Chambers passing the so-called “Exceptional Laws”: one suspended the right of habeas corpus to enable the detention of people plotting against the king, while a second imposed strict newspaper censorship. The third was the Law of the Double Vote, which changed the electoral laws to give extra say to the richest 25 percent of voters. As intended, this gave a huge boost to ultraroyalist candidates, who won landslides in the next two general elections.

That’s essentially what Polignac wanted to do in 1829 and 1830. He wanted new laws, imposing censorship to curtail so-called “abuses” from newspapers, and changing the electoral rules to favor wealthy ultraroyalists.25 Not 10 years prior, France had done just that through normal legal processes. And that 1820 legislature, like the one Polignac inherited in 1829, had a strong liberal element, until a crisis drove moderates to the right. So the idea that Polignac could accomplish his goals without doing a coup wasn’t crazy. It wasn’t likely, to be sure. But you can see where Polignac might have gotten the idea.

We know that Polignac had this idea because he told people about it constantly. For example, shortly before returning home to join the ministry, Polignac had a private meeting with the British foreign secretary, the Earl of Aberdeen, in which he shared his plans. As Aberdeen summarized the conversation to the Duke of Wellington, Polignac “seemed to think the greatest difficulty consisted in bringing the government to a determination to act with the necessary firmness against the revolutionary spirit which had grown up in the Chamber of Deputies and in the country, but which he felt confident might easily be controlled.”26

We know that Polignac had this idea because he told people about it constantly. For example, shortly before returning home to join the ministry, Polignac had a private meeting with the British foreign secretary, the Earl of Aberdeen, in which he shared his plans. As Aberdeen summarized the conversation to the Duke of Wellington, Polignac “seemed to think the greatest difficulty consisted in bringing the government to a determination to act with the necessary firmness against the revolutionary spirit which had grown up in the Chamber of Deputies and in the country, but which he felt confident might easily be controlled.”26

Right: George Hamitlon Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, by Thomas Lawrence, 1829. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

We’ll see in a little bit how accurate Polignac was at judging French politics. But in August 1829 the French parliament was in recess, not scheduled to return until the next year, and Polignac seemed disinclined to bring them back any sooner.

So in the meantime, there was no attempt to pass new right-wing laws. But neither was there the feared coup. Instead, this new ministry came into office and promptly did… nothing at all.

In with a whimper

Sauvigny writes that “the government wasted six full months in almost complete political inertia, weakening itself by internal divisions, emboldening its adversaries by its hesitations, and discouraging its supporters by its inaction.”

One minister wrote Villèle as early as Aug. 12 to lament that, “people cannot have confidence in us because we do not have confidence in ourselves.”27

The lack of public confidence in the ministry showed itself early, when they alienated a man the ministers could not afford to lose if they wanted to build a royalist alliance against the left. I’m speaking, of course, of our old friend François-René de Chateaubriand.

The lack of public confidence in the ministry showed itself early, when they alienated a man the ministers could not afford to lose if they wanted to build a royalist alliance against the left. I’m speaking, of course, of our old friend François-René de Chateaubriand.

Right: François-René de Chateaubriand, by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, sometime before 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The proud statesman had helped defeat Villèle in the Election of 1827, but made his peace with Martignac in exchange for the prestigious posting of ambassador to Rome. He was taking a holiday from this job when he heard about the new ministry’s appointment. In his memoirs, Chateaubriand describes the shock: “I had a moment of despair, for my mind was made up at once: I felt that I must retire.” Other historians see a little more ambivalence: Chateaubriand was deeply in debt and badly needed the 200,000-franc salary of his ambassadorship. It wasn’t until after he was bombarded with letters from friends urging him to resign that Chateaubriand formally notified Polignac. Regardless of the timing, it was a damaging loss for the ministry: Chateaubriand was the leader of a center-right faction whose votes they badly needed if they hoped to enact change legally.28

Another unaffordable loss came in November, when the long-anticipated rupture between Polignac and La Bourdonnaye burst into the open. This followed months of near-constant disagreement and arguments. Perhaps it was driven by La Bourdonnaye’s frustration with the government’s unexpected timidity, or with his difficulties doing the day-to-day administrative work at the Interior Ministry. Or perhaps he was maneuvered out by rivals in the cabinet. In any case, the breaking point came when Charles finally appointed Polignac as the ministry’s formal leader. As not infrequently happened in the Restoration, the government had been merely a collection of equal ministers until that point. But La Bourdonnaye was unwilling to play second fiddle to Polignac. “When I am staking my head, I want to hold the cards,” he declared, and quit.29 He had lasted four months out of the six Rochefoucauld had predicted.

La Bourdonnaye’s departure gave the cabinet some much-needed unity. But it also meant the loss of yet another right-wing faction. The legal path to enacting Polignac’s agenda was getting harder and harder to see.

One story making the rounds at the time had Polignac telling an ultraroyalist ally that he was not going to launch a coup.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” the ally replied. “Having only men who want a coup d’état for you, if you don’t have one, you’ll have no supporters left.”30

Adversaries to arms

As Polignac’s supporters dwindled, his enemies mounted. The press had greeted his very appointment with a virulent broadside of attacks.

One paper, La Tribune des Départemens, wrote about how the ministry recalled the White Terror of 1815, and said it represented forces of reaction who “live in the heart of our nation” and “constantly conspire against [France’s] prosperity, against its freedom, against its glory, and want at all costs to bring it under the yoke of… fanaticism and absolute power.”31

The newspaper Le Figaro — still around today! — published an Aug. 9 edition with a black border of mourning, and “news” items imagining the consequences that were about to befall France: arbitrary arrests, persecution of Protestants, the return of feudal rights, and other relics of the ancien régime.32 The paper managed to print 10,000 copies before police arrived to seize the issue’s printing plates; by evening, people were paying up to 10 francs for a copy of the contraband issue.33

The newspaper Le Figaro — still around today! — published an Aug. 9 edition with a black border of mourning, and “news” items imagining the consequences that were about to befall France: arbitrary arrests, persecution of Protestants, the return of feudal rights, and other relics of the ancien régime.32 The paper managed to print 10,000 copies before police arrived to seize the issue’s printing plates; by evening, people were paying up to 10 francs for a copy of the contraband issue.33

The Journal des Débats wrote on Aug. 10 about “perfidious counsels” that “misled Charles X and hurled him into a new career of disorder,” and on Aug. 15 that “No matter how you squeeze or wring this ministry, all that drips out is humiliation, misfortune, and danger.”34 This diatribe got the newspaper slapped with a libel charge, and its editor was sentenced to a 1,000-franc fine and six months in jail. But an appeals court reversed the judgment in December and acquitted the newspaper. Royalists saw this verdict as a dangerous development. To them, attacking the king’s ministers was in effect attacking the king who had chosen them. Liberals, in contrast, insisted that one could defend the king’s powers while criticizing the manner in which those powers were used.35

These opposition papers genuinely thought Polignac was a disastrous choice as prime minister. But the stridency of the rhetoric may have been driven by business concerns, too, as historian Robert Alexander has chronicled. Opposition to Polignac and Charles was increasingly widespread among the newspaper-reading public, and these people were seeking out commentary that shared their radicalism. New left-wing papers popped up, and mainstream papers adjusted their tones to compete. For example, one milquetoast paper in the city of Rennes agreed to start running political articles after being faced with the threat of a new radical journal starting up. Satisfied with the new tone, the radical paper was “duly cancelled.”36

And all these anti-Polignac attacks were only really possible because of one of the few big bills the Martignac ministry had managed to pass: an 1828 press law that removed censorship. As I mentioned in Episode 33, under the Martignac press law, newspapers could no longer be punished for a “general tendency… injurious to public peace,” and the king was no longer allowed to impose censorship by decree while the Chambers were out of session. Charles and Polignac very much wanted to censor the liberal press now, but their hands were tied.

Taxpayers on strike

Going beyond mere rhetoric, liberals began talking openly about civil disobedience in the event of the feared coup. The idea was a tax strike: if France had a budget that hadn’t been passed on strictly constitutional lines — say, one imposed as part of a royal coup d’état — Frenchmen should refuse to pay their taxes.

This tax strike was reported in Parisian newspapers starting on Sept. 11, 1829, allegedly as news reports about a group from Brittany that was trying to organize a tax strike. In fact, it seems likely that no such “Breton Association” actually existed before the Parisian newspapers made it up, but that didn’t matter much — real or not, the idea proved explosive. Tax-strike groups quickly popped up in 15 departments — including one actually in Brittany.37

Both sides saw this threat of a tax strike as hugely significant. In mid-July 1830, the Doctrinaire Duc de Broglie wrote a letter saying he was “quite certain that in case of a coup d’état the refusal to pay taxes would be prompt and universal, that this measure would be carried out without disorder, and that its success would be certain.” Broglie then added: “However, I should much prefer that things did not come to that.”38

.jpg#/media/File:Heim_-_Sosth%C3%A8ne_Ier_de_La_Rochefoucauld_(1785-1864).jpg) Rochefoucauld wrote to Charles on Sept. 15, 1829, to warn him about how things were going. “The further we advance down this vicious road, the more difficult retreat will be,” Rochefoucauld wrote. “All wise men are afraid. The Breton Association and the reception of Lafayette in Lyons are terrible warnings.”39

Rochefoucauld wrote to Charles on Sept. 15, 1829, to warn him about how things were going. “The further we advance down this vicious road, the more difficult retreat will be,” Rochefoucauld wrote. “All wise men are afraid. The Breton Association and the reception of Lafayette in Lyons are terrible warnings.”39

Left: Louis François Sosthènes I de La Rochefoucauld, Viscount of La Rochefoucauld, attributed to François Joseph Heim, c. 1814-1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Though Charles ignored most of Rochefoucauld’s desperate pleas to change course, he didn’t need to be told twice about the tax strike. Polignac’s government moved quickly to prosecute newspapers that had promoted the “Breton Association” both in Paris and around the country. All told 19 different cases were brought against 11 important liberal papers in the provinces, though many were acquitted. As historian Daniel Rader notes, “to Polignac’s cabinet, ‘revolutionary’ ideas were evil enough when confined to Paris, but how much greater a threat when spread by journalism to every corner of France and to the provincial electors!”40

The second of Rochefoucauld’s warnings is important, too — “the reception of Lafayette in Lyons.” In another sign of opposition strength in the French countryside, the old revolutionary Lafayette headed down to southern France for a speaking tour and received a triumphant reception. In Grenoble, he was given a “wreath of silver oak leaves” as “an emblem of the force that the Grenoblois, like him, would be able to summon to uphold their rights and the constitution.” At Lyons, he was greeted by an escort of 500 locals riding horses. Meanwhile the king’s daughters-in-law, the Duchesse d’Angoulême and the Duchesse de Berry, went on their own tours and were received much more cooly.41

With friends like these

The Polignac government didn’t just lie back and take these blows lying down. Besides the blunt instrument of prosecuting liberal journalists, pro-Polignac newspapers fought back in print.

One ultraroyalist paper wrote on Aug. 10 that France needed vigorous action, especially against abuses by the opposition press: “Public liberties can only be guaranteed by rigorous laws… It is because we love freedom… that we want the severe repression of excesses,” the paper wrote. “We would unhesitatingly prefer the slavery of the press to her unpunished license.” Another rejected the liberal claims that they were only criticizing the king’s ministers, not the king himself: “It is… the King himself whom they have called to their bar. No intermediary between outrage and the sacred person… of the monarch. The King alone has willed; the King alone has acted.”42

Other Ultra papers heaped scorn on the opposition, who they said they were a spent force. For La Quotidienne, the forces of “revolution” were characterized by “useless shouting” and “pitiful exaggerations,” by “want of unity” and “infighting,” and “in the final analysis by the emptiness of its reforms.” “What is certain,” the paper argued, “is that the time would be propitious to organize a savior ministry.” Gleefully, La Quotidienne said that the reported names of Polignac et al had “enough royalism… to justify the cries of alarm from Le Constitutionnel.”43

But while the Right was unanimous in its scorn for the Left and support for the king’s prerogatives against parliament, that unity broke down when it came to details. French ultraroyalists were as divided as they accused the liberals of being. Just looking at the universe of Ultra newspapers, the Gazette de France supported Joseph de Villèle’s faction, while the Quotidienne was anti-Villèlist, and the radical Drapeau Blanc was pro-Polignac.44 These rival factions would unite or clash depending on the issue of the day. That meant Polignac, trying to govern with only the Right, couldn’t count on his own side having his back.45

New: Orléans

That’s not to say the opposition was all of one mind. There were lots of different factions opposed to Polignac, too, from left-wing republicans, to liberal constitutional royalists, to some genuine Ultras who strongly supported a powerful French monarchy but thought Polignac was undermining his own cause.

One faction of emerging importance were the so-called “Orléanists,” a group holding the borderline treasonous view that Charles X should be replaced as French king with his more liberal cousin Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans.

One faction of emerging importance were the so-called “Orléanists,” a group holding the borderline treasonous view that Charles X should be replaced as French king with his more liberal cousin Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans.

Left: Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans, by Frédéric Millet, 1827. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve talked about Louis-Philippe a lot on the show. Way back in Episode 2, I mentioned how he had hoped to be named king back in 1815. In Episode 15, I described the public scene Louis-Philippe made in 1820, after the healthy birth of Charles’s grandson ended the chances of the Orléans family inheriting the throne. And in Episode 28, I described how one of the first things Charles did after taking the throne was meet Louis-Philippe to mend fences. The king granted his cousin honors and ended the cavalcade of indignities that Louis XVIII had gleefully inflicted on the Orléans family. And it worked! Even though the ultraroyalist Charles and the liberal Louis-Philippe were far apart politically, they got on well personally, and under Charles we don’t hear stories of Louis-Philippe scheming for the throne like we did early in Louis XVIII’s reign.

As historian Pamela Pilbeam wrote, “the Duc d’Orléans was no subversive.” While he disliked Charles’ politics, he also didn’t want another revolution that might drive him into exile for a second time. Plus, Charles’ reign had been personally good for him — Louis-Philippe had gotten more money than anyone else from the Émigré’s Billion law that Charles pushed through in 1825.46

Of course, the fact that Louis-Philippe wasn’t a subversive didn’t mean he was a hermit, either. The duke took care to cultivate a public image as a liberal, patriotic, forward-thinking prince.

For example, he commissioned the artist Horace Vernet to produce four epic paintings of battles from the Revolution and Napoleonic Wars — two of which just so happened to include a young Louis-Philippe defending his country in uniform.47

Louis-Philippe also made waves with a very personal decision: how he educated his sons. Try to conceal your gasps when I tell you that Orléans sent his sons to a school to learn instead of having them tutored in private. This was sufficiently scandalous that Louis XVIII summoned his cousin for a horrified lecture. “Everyone will call each other tu and toi; they will play silly games together,” the king said, referring to the French informal second-person pronouns. Faced with this royal upbraiding, Louis-Philippe stood his ground, saying that his sons’ ideas “should be in harmony with those of the nation and of his generation.” This was of course not merely a pedagogical choice — it was “a political and cultural statement.”48

Louis-Philippe also made waves with a very personal decision: how he educated his sons. Try to conceal your gasps when I tell you that Orléans sent his sons to a school to learn instead of having them tutored in private. This was sufficiently scandalous that Louis XVIII summoned his cousin for a horrified lecture. “Everyone will call each other tu and toi; they will play silly games together,” the king said, referring to the French informal second-person pronouns. Faced with this royal upbraiding, Louis-Philippe stood his ground, saying that his sons’ ideas “should be in harmony with those of the nation and of his generation.” This was of course not merely a pedagogical choice — it was “a political and cultural statement.”48

Ferdinand Phillipe, duc de Chartres, eldest son of Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans. Portrait by Ary Scheffer, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This deliberate public image resonated with a certain type of Frenchman — center-left royalists who wanted France ruled by a modern constitutional monarch, not a throwback to the ancien régime. So even though Louis-Philippe doesn’t appear to have been scheming himself, that didn’t mean other people didn’t look at the Duc d’Orléans and see a potential king. The fact that Louis-Philippe was right there, just hanging around, as Charles became more and more extreme, was awfully convenient.

The National

The most prominent way these Orléanists promoted their cause was in the press. In January 1830, another recurring figure on the show wrote an article that purported to be a simple historical discussion of England’s “Glorious Revolution” of 1688:

In the 1640s a revolution occurred in England and Charles I died on the scaffold. In 1688 there was no revolution; James II fled without pursuit and there was no confusion. It was simply a matter of one family being replaced by another. One dynasty did not know how to rule a new social order and another, more knowledgable and the nearest kin of the fallen monarch, replaced it.49

The extremely thinly veiled implication here was that Charles X was James II of England, who had been chased out for his backwardness. And if Charles X was James II, then everyone knew who Charles’s “nearest kin” was: the Duc d’Orléans.

The writer of this seditious article was Adolphe Thiers, already one of the most famous journalists in Paris in his early 30s. Writing for papers like Le Constitutionnel, Thiers had not only proven himself a master of slashing prose, he had also shown uncommon initiative for a journalist by doing things like taking a reporting trip to a war zone. (See Supplemental 9 for more on that!) But by 1829, Thiers felt like he was in a bit of a rut, and made plans to join a naval expedition sailing around the world. Not only would this be a fun adventure, it would give him plenty of material for a new book. But Thiers’s friends persuaded him to cancel this trip when Charles appointed Polignac — his sharp pen would be needed back in France.50

The writer of this seditious article was Adolphe Thiers, already one of the most famous journalists in Paris in his early 30s. Writing for papers like Le Constitutionnel, Thiers had not only proven himself a master of slashing prose, he had also shown uncommon initiative for a journalist by doing things like taking a reporting trip to a war zone. (See Supplemental 9 for more on that!) But by 1829, Thiers felt like he was in a bit of a rut, and made plans to join a naval expedition sailing around the world. Not only would this be a fun adventure, it would give him plenty of material for a new book. But Thiers’s friends persuaded him to cancel this trip when Charles appointed Polignac — his sharp pen would be needed back in France.50

Right: Tony Goutière, “Sketch of a young Adolphe Thiers.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But this pen would not be writing for the liberal standard-bearer, Le Constitutionnel. Instead, the references to Charles’s “more knowledgable… nearest kin” were written in a brand new paper, Le National. It was the most prominent of a new group of militant left-leaning newspapers, with two major assets: great writers and deep pockets.

The paper’s origins date to the fall of 1829, the early months of the Polignac ministry, when a group of like-minded people came together. One of them was Thiers, who had tried to push Le Constitutionnel to oppose Charles more forcefully. In this he was largely thwarted by some of the paper’s owners, who didn’t want to rock the boat too much, and saw Thiers as “the paper’s ‘pet’ radical.” Thiers was joined by a few like-minded writers: his longtime friend François Mignet, and the brilliant but turbulent Armand Carrel. Listeners with stupendous memories might remember Carrel, who participated in the Carbonari conspiracies as a young man, and later looked back on them with bewilderment. In Episode 23, I quoted him saying: “Why did we have the mad idea that a government supported by laws and by the weight of inertia of 30 million men could be overturned by the plots of law students and second lieutenants?”51

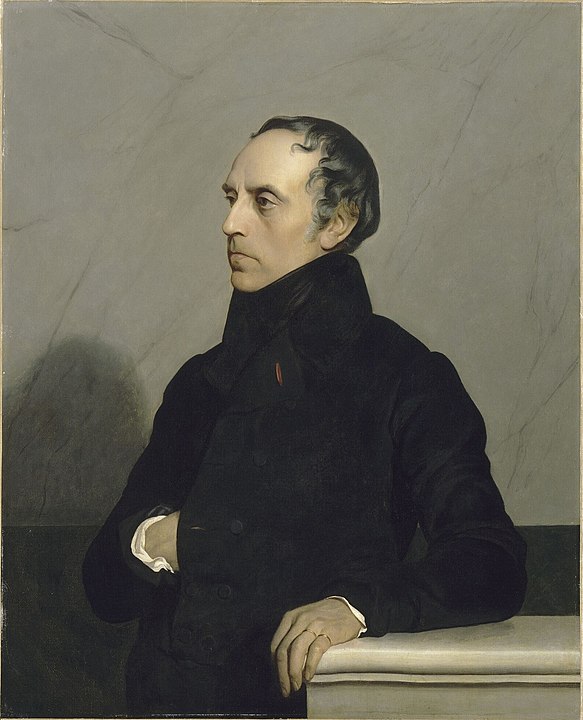

Above: Armand Carrel, by Ary Scheffer, 1833. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, by Ary Scheffer, 1828. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

These young writers crossed paths with some political big-wigs who had money and influence and wanted to bring that to bear. One of these was the liberal banker and politician, Jacques Laffitte, who put up some of the money for the new paper. Another was the Baron Louis, a center-left politician who had served as Minister of Finance under Louis XVIII, and who was the uncle of Admiral Henri de Rigny. Most notorious of all was the statesman Talleyrand, now 75 years old and still keenly involved in politics. Historians have debated whether Talleyrand actually funded Le National or merely encouraged it. The most likely truth seems to be the verdict colorfully expressed by Chateaubriand, who personally loathed Talleyrand: “Prince Talleyrand did not add a sou to the till, he only soiled the spirit of the journal by throwing into the common fund his share of treason and corruption.” In other words: Talleyrand didn’t invest in the paper, but he did lend it his invaluable insight and connections.52

These young writers crossed paths with some political big-wigs who had money and influence and wanted to bring that to bear. One of these was the liberal banker and politician, Jacques Laffitte, who put up some of the money for the new paper. Another was the Baron Louis, a center-left politician who had served as Minister of Finance under Louis XVIII, and who was the uncle of Admiral Henri de Rigny. Most notorious of all was the statesman Talleyrand, now 75 years old and still keenly involved in politics. Historians have debated whether Talleyrand actually funded Le National or merely encouraged it. The most likely truth seems to be the verdict colorfully expressed by Chateaubriand, who personally loathed Talleyrand: “Prince Talleyrand did not add a sou to the till, he only soiled the spirit of the journal by throwing into the common fund his share of treason and corruption.” In other words: Talleyrand didn’t invest in the paper, but he did lend it his invaluable insight and connections.52

The net result was a new newspaper with sharply written articles at — but not over — the cutting edge of French politics at the time. Le National was more radical than Le Constitutionnel, but it was less extreme than the openly republican papers popping up about this time. This was the sweet spot of the radicalizing French newspaper market, and Le National capitalized.53

The Orléanist tone of Le National was not an occasional thing. It suffused practically every issue. Even in December 1829, before the new paper launched, Rochefoucauld had heard gossip that “M. de Talleyrand has thrown himself into the Orléanist faction.”54 Meanwhile the thinly veiled calls for a King Louis-Philippe filled the paper. In February 1830, Thiers wrote an article suggesting that France’s political drama was primarily a “question… of persons,” and that the right person for the job was one who had “the simple, modest, solid virtues which a good education can always assure the heir to the throne.” The allusion to how Louis-Philippe educated his sons should be clear.

That February article got the paper indicted. Thiers himself escaped consequence, but the paper’s editor was sentenced to three months in jail and a 1,000-franc fine. This didn’t deter the paper at all; it continued its aggressive attacks against Polignac and Charles.55 Meanwhile other papers were tugged along in its wake. Even Le Globe, a highbrow literary journal, joined the fray — in February 1830, it switched to daily publication and a focus on politics.56 In that month, the new Globe published an article, “France and the Bourbons.”

Parliament is about to open and the Monarchy finds itself face to face with the nation… There is nothing so dismal or humiliating for a great people as to be forced, each morning, to foresee or to frustrate the follies of an authority both menacing and despicable.

Already taking an aggressive stand, the article went on to note that after the Aug. 8 ministry was appointed, “the words of 1688 and the Stuarts returned.”57 Le National may have been the most aggressive, but Orléanist sentiment was showing up all over!

The King’s Speech

But as I noted just now, the French parliament was about to finally return. The long period of inactivity for the Polignac ministry was over, and it was time for the confrontation with the Chamber of Deputies that everyone had been expecting.

This was not quite the same Chamber of Deputies that limped away with Martignac the prior summer. There were 29 different by-elections in 1829, which resulted in a net gain of 7 more liberal deputies. One last special election came in January 1830, when voters in Normandy elected the Doctrinaire writer François Guizot to the Chambers. Guizot had finally turned 40, the minimum age to be a deputy, and his friends found him a likely seat. Though Guizot did not live in Normandy, allies purchased him some property there and got him elected purely on the national issue of opposition to Polignac.58

This was not quite the same Chamber of Deputies that limped away with Martignac the prior summer. There were 29 different by-elections in 1829, which resulted in a net gain of 7 more liberal deputies. One last special election came in January 1830, when voters in Normandy elected the Doctrinaire writer François Guizot to the Chambers. Guizot had finally turned 40, the minimum age to be a deputy, and his friends found him a likely seat. Though Guizot did not live in Normandy, allies purchased him some property there and got him elected purely on the national issue of opposition to Polignac.58

Right: François de Guizot, circa 1837, by Jehan Georges Vibert after Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The net effect was that the Chamber of Deputies had grown even more hostile to Polignac than it had been when he first took office, hoping to enact reactionary change legally.

Before Polignac could even hope to ask for the Chamber to pass a new censorship law or change the electoral system, though, the first order of business was for the king to welcome the Chambers back with a speech — and for the Chambers in turn to vote an official response.

We’ve seen these speeches spark conflicts in the past. In 1821, the Chamber of Deputies approved a response to Louis XVIII congratulating him “on your continuously friendly relations with foreign powers, in the just confidence that such a valued peace is not purchased by sacrifices incompatible with the honor of the nation and the dignity of the crown.” Louis considered dissolving the Chambers but confined himself to a sharp lecture and reshuffling his cabinet to shore up support.59

In 1828, the Chambers responded to Charles X’s address by adding a line criticizing Charles’s recently departed prime minister, Joseph de Villèle: “The unhappy French people have repudiated the deplorable system which rendered your promises meaningless.” Charles considered dissolving the Chambers, but confined himself to a lecture and reshuffling his cabinet to shore up support.60

So here we are in 1830, with tensions already at a fever pitch. Charles arrived at the Chambers on March 2 to present a speech that everyone knew could set off a fight. His exact words had been drafted and debated by his ministers, with a broad consensus that the king should be firm instead of conciliatory, but debate about just how confrontational he should be. In the end, proposals to moderate the tone lost.61 The day before, Charles let one of his loyal courtiers read the draft. When she told him it was “rather severe,” Charles is said to have responded, “It is well deserved. Do you not know, then, how malevolence interprets my actions and even my words, that everywhere, and above all in Paris, intrigues are being formed against my authority? Oh, I swear to you, I cannot endure it…”62

So here we are in 1830, with tensions already at a fever pitch. Charles arrived at the Chambers on March 2 to present a speech that everyone knew could set off a fight. His exact words had been drafted and debated by his ministers, with a broad consensus that the king should be firm instead of conciliatory, but debate about just how confrontational he should be. In the end, proposals to moderate the tone lost.61 The day before, Charles let one of his loyal courtiers read the draft. When she told him it was “rather severe,” Charles is said to have responded, “It is well deserved. Do you not know, then, how malevolence interprets my actions and even my words, that everywhere, and above all in Paris, intrigues are being formed against my authority? Oh, I swear to you, I cannot endure it…”62

Left: King Charles X of France, by William Corden the Elder. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The speech itself took place in the Louvre, and the room was packed to the brim. Almost all the Deputies and Peers were present. So were all the various court officials, and crowds of onlookers in the galleries.63 After an opening invocation, Charles invited the Peers to sit down, gave the deputies “permission to sit,” and began.64 In small groups, Charles was noted as quite charming, but this apparently didn’t translate to oratory. One observer noted:

Charles X had a shrill voice without resonance, did not pronounce his words clearly, and read his speeches clumsily. Upon these occasions his usual gracefulness abandoned him. Accidental circumstances also contributed to hamper him: as he was very nearsighted, his speeches were written out for him in a large hand, and hence it was necessary for him to be constantly turning pages, which did not add to his dignity.65

Much of the speech focused on questions of foreign policy, which I’ll cover in a future episode — this script is already long enough. Charles got to announce that the kingdom’s budget was balanced, and to propose new public works — both easy applause lines.66

But the close of the speech concerned domestic politics. And here I’m going to quote the key passage from Charles’s address in full, because this is going to be important.

The Charter has placed the public liberties under the protection of the rights of my crown. These rights are sacred, and my duty to my people is to transmit them intact to my successors. Peers of France, Deputies of the departments, I am confident of your cooperation in implementing the good measures I propose. You will spurn with scorn the perfidious insinuations that malice is trying to promote. If criminal maneuvers were to place obstacles in the way of my government, something which I do not foresee, I shall find the power to surmount them in my determination to maintain public order, in the just confidence of the French people, and in the love that they have always shown for their king.67

The tone of this closing section is unmistakable nearly two centuries later. Charles is promising to defend the rights of his crown with “determination to maintain public order.” He describes attacks from the opposition as “perfidious insinuations” that threaten to rise to “criminal maneuvers.” This section was followed by a moment of dead silence, followed by applause from the royalist benches and continued silence from the opposition.68

But before I discuss the response of the Chambers, there’s one more moment we need to revisit from this closing paragraph. As Charles read the line, “if criminal maneuvers were to place obstacles in the way of my government, something which I do not foresee,” he gestured with unusual animation — and knocked the diamond-studded hat off his head. It fell to the ground and rolled over to the feet of Charles’s cousin, the Duc d’Orléans. Louis-Philippe picked up the king’s hat and returned it, but observers did not hesitate to speculate about the “uncanny” event.69

The Chamber responds

There was no real disagreement about what Charles had meant by this closing passage: a threat to launch a coup d’état. The difference was Ultra newspapers generally thought this was a good thing. The Drapeau Blanc cheered that the “faithless orators and seditious journalists” were going to be swept away. The Gazette de France emphasized the legality of the king’s powers and accused the Left of being hysterical. La Quotidienne said all that remained was for Charles to follow through on his words.70

The opposition press reacted as you might expect. Thiers in the National said the speech was “a repetition in four lines of all the Ministry has been saying for eight months.” Le Constitutionnel said that if “resistance is nothing more than a ‘guilty maneuver’, then there is no more Charter”. Le Globe called on “all good citizens” to “arm themselves with courage” and looked toward the politicians: “A dark future is perhaps approaching, but all hope is not yet lost: The Chamber has said nothing.”71

The Chambers were definitely going to say something. The question was what. The right-leaning Chamber of Peers approved a bland response over a furious dissent from Chateaubriand. But even the Peers slipped in some gentle rebukes, such as a line saying “the rights of your crown are no less dear to your people than their liberties.”72

But it was the left-leaning Chamber of Deputies where the decisive action lay. Any hopes Charles might have had of the Deputies caving must have been swept away the next day, when the Deputies voted on five nominees for the chamber’s presiding officer. Charles could appoint any one of the top five vote-getters, but none of the five men were Ultras. Reluctantly, Charles appointed the man he saw as the least-bad option, the Doctrinaire orator Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. And Royer-Collard was not feeling especially moderate right now — after the king’s address, he had said the Deputies “must strike hard and swiftly, and not allow time for the folly and ineptitude of a few men to destroy liberty.”73

But it was the left-leaning Chamber of Deputies where the decisive action lay. Any hopes Charles might have had of the Deputies caving must have been swept away the next day, when the Deputies voted on five nominees for the chamber’s presiding officer. Charles could appoint any one of the top five vote-getters, but none of the five men were Ultras. Reluctantly, Charles appointed the man he saw as the least-bad option, the Doctrinaire orator Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. And Royer-Collard was not feeling especially moderate right now — after the king’s address, he had said the Deputies “must strike hard and swiftly, and not allow time for the folly and ineptitude of a few men to destroy liberty.”73

Left: Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard, 1819, by Louis-Léopold Boilly. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

After several days of work, a committee packed with opposition deputies drafted a response to the king. This also deserves to be quoted at length, because it’s very important. I’m going to break the key paragraph down into six sentences for easier analysis.

Sire, the Charter which we owe to the wisdom of your august predecessor, and which Your Majesty has declared a firm determination to consolidate, consecrates as a right the participation of the country in the discussion of public affairs.

This intervention ought to be, and is in effect, indirect, wisely regulated, and bound by limits which are minutely defined, and which we shall never permit anyone to exceed.

It is also positive in its results, because it makes necessary permanent concurrence between the policies of your government and the wishes of your people as an indispensable condition for the regular conduct of public affairs.

Sire, our loyalty and devotion compel us to say to you that this concurrence does not exist.

An unjust distrust of the feelings and the mind of France is the prevailing attitude of the administration.

Your people are offended because this is injurious to them; they are troubled because their liberties are threatened.74

When this draft was first read out to the Chamber of Deputies, “all was disorder for a few minutes,” followed by days of debate. Everyone knew the implication if the full Chamber approved this response: either the Polignac ministry would fall, or Charles would dissolve the Chamber of Deputies. And, frankly, everyone knew the latter was much more likely.75

But before we get to that debate, I want to dig a little deeper into this response. One thing that strikes me, for a passage everyone correctly interpreted as a gauntlet thrown at the king, is how conservative and royalist it is. This is not rooted in an appeal to popular sovereignty. There is nothing revolutionary or democratic about it. Compare Sentence 2, which says the people’s role in government should be “indirect” and “bound by limits,” with the sentiments of the 1789 “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.” That opened by claiming that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights” and went on to say that “The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation.”

This conservative and royal nature was no accident. Many of the opposition deputies would have liked to vote for a more radical address, including Lafayette, who had helped write the “Declaration of the Rights of Man” back in 1789. But the left-wing deputies agreed to let “their moderate allies” take the lead in the interests of gathering as large a coalition as possible. These moderates were almost congenitally allergic to conflict, and as far as people like Lafayette were concerned, the willingness of folks like Royer-Collard to fight was a gift that should be welcomed.76

This conservative and royal nature was no accident. Many of the opposition deputies would have liked to vote for a more radical address, including Lafayette, who had helped write the “Declaration of the Rights of Man” back in 1789. But the left-wing deputies agreed to let “their moderate allies” take the lead in the interests of gathering as large a coalition as possible. These moderates were almost congenitally allergic to conflict, and as far as people like Lafayette were concerned, the willingness of folks like Royer-Collard to fight was a gift that should be welcomed.76

Right: An elderly Marquis de Lafayette, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But even if this address was not revolutionary, it still represented an unmistakable ideological challenge. Against the “sacred” rights of Charles’ crown, the Deputies threw up the “consecrated” right of the people’s representatives to participate in public affairs.

Charles’s ministers, and their supporters in the Ultra press, insisted that the one of the sacred rights of his crown was for the king to appoint whatever ministers he so chose. As one of those ministers argued in the ensuing debate: “The day when it is established that the Chamber can reject the ministers of the King and impose others on him, which will be their ministers, and not the ministers of the King… on that day France will be a republic.”77

The opposition loudly insisted they did not want a republic. Nor were they proposing a situation such as exists in the United Kingdom today, where the parliament chooses ministers and a purely ceremonial monarch formally appoints them. As far as the deputies were concerned, the king had a genuine right to appoint who he wanted as his ministers — so long as those appointees had the support of parliament. For example, if the Chambers wanted Chateaubriand to be foreign minister but the King didn’t like Chateaubriand, Charles could appoint someone else — it just couldn’t be someone like Polignac, who the Chambers rejected.78

Note also the contrast: the Deputies said that “an unjust distrust of the feelings and the mind of France” characterized the king’s ministers. But Charles, before the speech, had complained about “how malevolence interprets my actions and even my words.” Both sides saw themselves as reasonable and justified, and the other as holding unjust suspicions.

Dissolution

The debate in the Chamber of Deputies was a grand affair. Almost all the deputies were in their seats, and almost all the king’s ministers were there, too. But all those speeches changed nothing. A proposal to change the reply to one of milder rebuke got only 30 votes — there were factions for a strong rebuke, and for no rebuke at all, but no appetite for half-measures. Leading moderates worked hard behind the scenes to keep swing voters from wavering.79

Ultimately the Chamber of Deputies voted 221 to 181 to approve their response, a direct challenge to Charles’s royal authority as he saw it. It was almost immediately dubbed the “Address of the 221.”

But that vote wasn’t the end of it — a delegation of deputies then had to go present this address to the king. Charles knew what was coming, of course, and his ministers had debated the precise tone of their response. The assumption was that Charles would dissolve Chamber of Deputies as a response to this insult. Some ministers argued for patience: This was a purely symbolic issue, but if Charles waited, the opposition would likely force things by doing something like voting down a budget. Then Charles could accuse the opposition of harming the country and dissolve the Chambers from the political high ground. Another minister proposed an alternative solution: “He could garner 40 additional votes if they were willing to pay the price.” But Charles rejected using corruption to buy off opponents, and he rejected playing the waiting game. He would act firmly.80

Charles’s stubbornness was rooted in the old king’s long memories. He remembered the fall of his oldest brother in the 1789 French Revolution, and was convinced that revolution had happened because Louis XVI had made too many concessions. And chief among those concessions, Charles believed, was agreeing to dismiss his chief minister, the Baron de Breteuil, to calm things down after the Fall of the Bastille. “I have, unfortunately, more experience in this matter than you,” Charles told his ministers. “[You] are not old enough to have witnessed the Revolution; I remember what happened then; the first concession that my unhappy brother made was the signal for his fall… [his opponents] also made protestations of love and fidelity, all they asked for the was the dismissal of his ministers, he gave in, and all was lost.”81 It seemed reasonable for Charles to dismiss Polignac and appoint a minister who could work with the Chamber of Deputies — but Charles saw that as a deadly trap, a slippery slope that led to doom.

On March 18, 1830, Royer-Collard led 46 deputies to the Tuileries Palace to read the reply to the king. François Guizot recorded that Charles listened “with becoming dignity and without any air of haughtiness or ill humor,” and that his answer was “brief and dry” rather than raging. The king said:

Gentlemen, I have heard the address which you have presented to me. I had the right to count on the concurrence of the two chambers in order to accomplish what I had in mind. My heart is distressed at seeing the deputies of the departments declare, on their part, that this concurrence does not exist. Gentlemen, I announced my plans in my speech at the beginning of the session. These resolutions are unalterable… My ministers will inform you of my intentions.82

Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard presents the Address of the 221 to King Charles X of France, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Those intentions were not an immediate dissolution of the Chambers. Instead, Charles “prorogued” parliament — suspended their session — until Sept. 1. There was no intention of actually calling the deputies back in September. Instead, this was a delaying tactic so Charles could dissolve parliament and call new elections at the moment of his choosing. Some people then and since felt the best time for elections was immediately, to give the opposition as little time as possible to organize. But Charles and Polignac had reasons of their own to wait — reasons we’ll have to cover in a future episode.

My thanks to Josh Zucker for providing the promo that kicked off this episode. Check out his show, Grand Dukes of the West: A History of Valois Burgundy, at granddukesofthewest.com or wherever you get podcasts. Alternatively, you can get a link to his show at thesiecle.com/episode34, where you’ll also find a full transcript of this episode with photos, links and 82 footnotes.

Thank you also to Robin Beasley for providing editorial assistance for this episode.

If you’re liking the show, please help spread the word by sharing links on social media. You can also rate or review the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or Podchaser, which helps bring in new listeners. You can also, if you’re so inclined support The Siècle with one-time donations or Patreon pledges for as little as $1 per month. That helps me cover hosting costs, buy new books, and hopefully fund a future research trip to Paris. You can find links to donate and other ways to help the show online at thesiecle.com/support.

Thank you to my latest supporters, including one-time donors William, Rosemary and Ruben-Erik, and Patreon subscribers CJ Newell, Ali Saribas, Fernando López Ojeda, August Filbert and Miguel Duarte.

Now, it’s right back to work on the show. But we’re not going to forge straight ahead into the Election of 1830. Before that climactic showdown, there’s a few more things we need to put on the board. One of them is Charles’s foreign policy in 1830, which I hinted at above. But there’s something else that has people upset about Charles’s reign. Join me next time for Episode 35: L’Économie.

-

François-René de Chateaubriand, France’s foreign minister from 1822-4, originally appointed Polignac to his post as ambassador to Great Britain. Reflecting on Polignac later, Chateaubriand said he had done this over Villèle’s objection. François-René de Chateaubriand, The Memoirs of François René Vicomte de Chateaubriand sometime Ambassador to England, vol. 5 (of 6), translated by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, and London: Freemantle and Company), Project Gutenberg, 2017. ↩

-

Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 269-70. ↩

-

Ernest Daudet, Le ministère de M. de Martignac; sa vie politique et les dernières années de la restauration (Paris: E. Dentu, 1876), 293. ↩

-

Daudet, Le ministère de M. de Martignac, 304-5. Beach, 291. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 132. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 421. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 421. ↩

-

Daniel L. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827-30 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 95. Chateaubriand, Memoirs, Project Gutenberg. ↩

-

Note: The original text of this episode, as recorded in the audio, incorrectly attributed this quote to the “Duc de Doudeauville.” While Rochefoucauld would eventually become the second Duc de Doudeauville and published his memoirs under that name, at the time his father Ambroise was still alive and held the title of duke. While Ambroise held similar opinions to his son — championing the monarchy but critical of Polignac — the quotes here and later in this episode come from the son, Sosthènes de la Rochefoucauld. Louis François Sosthènes de la Rochefoucauld, Duc de Doudeauville, Mémoires de M. de La Rochefoucauld, duc de Doudeauville [fils], vol. 9 (Paris: Michel-Lévy frères, 1863), 503-4. See also Ambroise-Polycarpe de la Rochefoucauld, duc de Doudeauville, Mémoires de M. de La Rochefoucauld, duc de Doudeauville [père] (Paris: Michel-Lévy frères, 1861), 318-9. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 421. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 229-30. ↩

-

See Episode 30. ↩

-

Le Moniteur universel, Aug. 9, 1829, accessed via Dignole: https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu%3A584118#page/1/mode/2up. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 422. Daudet, Le ministère de M. de Martignac, 317. Rigny’s uncle had served as a minister under Élie Decazes, and Rigny himself would eventually accept an appointment as naval minister — but not until a future, more moderate government. ↩

-

See Episode 15. Historian Philip Mansel calls Polignac asking Decazes to join his ministry “a startling vindication of his role before 1820 which would have amused, but not surprised, Louis XVIII.” Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 414. ↩

-

Literally a “fusion constitutionnelle,” or “constitutional fusion.” ↩

-

Daudet, Le ministère de M. de Martignac, 301-2. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 96, 142. ↩

-

The Earl of Aberdeen to Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, in Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 6 (London: John Murray, 1867), 34-6. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 424-5. ↩

-

Chateaubriand, Memoirs, Project Gutenberg. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 424. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 293. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 425. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 424-5. ↩

-

La Tribune des Départemens, Aug. 9, 1829, accessed via RetroNews: https://www.retronews.fr/journal/la-tribune-des-departemens/09-aout-1829/1221/2761207/2. ↩

-

Figaro, Aug. 8, 1829, accessed via Bibliothèque Nationale de France. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 100. ↩

-

Le Journal des Débats, Aug. 10, 1829, Aug. 15, 1829, accessed via Bibliothèque Nationale de France. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 423. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 303. While the courts sided with the newspaper, the court took a different perspective. The Duchesse d’Angoulême pointedly refused to receive the judges of the appellate court that ruled for the Journal des Débats, dismissing them with a haughty “Pass on, gentlemen, pass on.” ↩

-

Robert Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition: Liberal Opposition and the Fall of the Bourbon Monarchy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 253-4. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 124-7. ↩

-

Achille-Léon-Victor, duc de Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, 1785-1820, ed. and trans. Raphael Ledos de Beaufort, vol. 2 (London: Ward and Downey, 1887), 305-6. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 127-8. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 93-4. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 424. ↩

-

Le Drapeau Blanc, Aug. 10, 1829, accessed via RetroNews: https://www.retronews.fr/journal/le-drapeau-blanc/10-aug-1829/623/1809955/2. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 96. ↩

-

La Quotidienne, Aug. 9, 1829, accessed via RetroNews: https://www.retronews.fr/journal/la-quotidienne/9-aout-1829/737/2135937/1. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 30-34. ↩

-

Pamela Pilbeam, The 1830 Revolution in France (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 31. ↩

-

Pilbeam, The 1830 Revolution in France, 81. ↩

-

Katie Hornstein, Episodes in Political Illusion: The Proliferation of War Imagery in France (1804-1856), PhD diss. (University of Michigan, 2010), 118. ↩

-

Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 100. ↩

-

J.P.T. Bury and R.P. Tombs, Thiers, 1797-1877: A Political Life (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1986), 16-7. ↩

-

Sylvia Neely, Lafayette and the Liberal Ideal, 1814-1824: Politics and Conspiracy in an Age of Reaction (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 222. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 112-6. Bury & Tombs, Thiers, 20-21. ↩

-

For example, Le National praised “the republican spirit” — radical words for the time — but never actually called for a republic. Instead it explicitly endorsed the virtues of constitutional monarchy. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 119. ↩

-

The story did not end so happily for Le National’s editor, Auguste Sautelet, who was hit with the three-month sentence for publishing Thiers’s article. While free on appeal of his sentence in May 1830, Sautelet killed himself with a pistol. The prospect of time in prison appears to have been a factor, along with unrelated personal issues. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 183-4. Irene Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 1814-1881 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), 57. ↩

-

The historian Augustin Thierry wrote to François Guizot, “What do you think of the Globe since it has changed its character? I don’t know why I am vexed to find all these trifling points of news and daily discussion in it. Formerly we concentrated our thoughts to read it, but now that is no longer possible, the attention is distracted and divided.” Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 122. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 160-1, 181. ↩

-

Sherman Kent, The Election of 1827 in France (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1975), 188. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 111. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 176-8. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 256. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 408. ↩

-

David H. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 18-19. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 19. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 162. ↩

-

I have here blended two translations, one by Vincent Beach and the other by Lynn Case. Beach, Charles X, 308. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 427. ↩

-

Price reports that Louis-Philippe returned the hat promptly, while Pinkney says Louis-Philippe held it until the end of the speech. Price, The Perilous Crown, 131. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 19. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 162-3. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 164-5. ↩

-

This translation is that of Vincent Beach, except I followed Lynn Case in separating the two parts of sentence 6 here with a semicolon instead of a period. Beach, Charles X, 310-1. De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 428-9. ↩

-

Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition, 244. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 20-1. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 21. Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition, 244. ↩

-

De Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 429. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 129-30. Munro Price, The Road from Versailles: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and the Fall of the French Monarchy. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 98-99. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 312-3. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 22-3. ↩