Episode 40: The Journalists

Charles de Rémusat was in his home office around 10 in the morning, busy writing his next article for the Globe newspaper — a scathing attack on an ultraroyalist pamphlet — when a friend and fellow journalist stopped by to tell him he was wasting his time. There was no point in rebutting a pamphlet calling for King Charles X to launch a coup, the friend said. “You don’t know anything. The coup is in the Moniteur.”1

Charles de Rémusat was in his home office around 10 in the morning, busy writing his next article for the Globe newspaper — a scathing attack on an ultraroyalist pamphlet — when a friend and fellow journalist stopped by to tell him he was wasting his time. There was no point in rebutting a pamphlet calling for King Charles X to launch a coup, the friend said. “You don’t know anything. The coup is in the Moniteur.”1

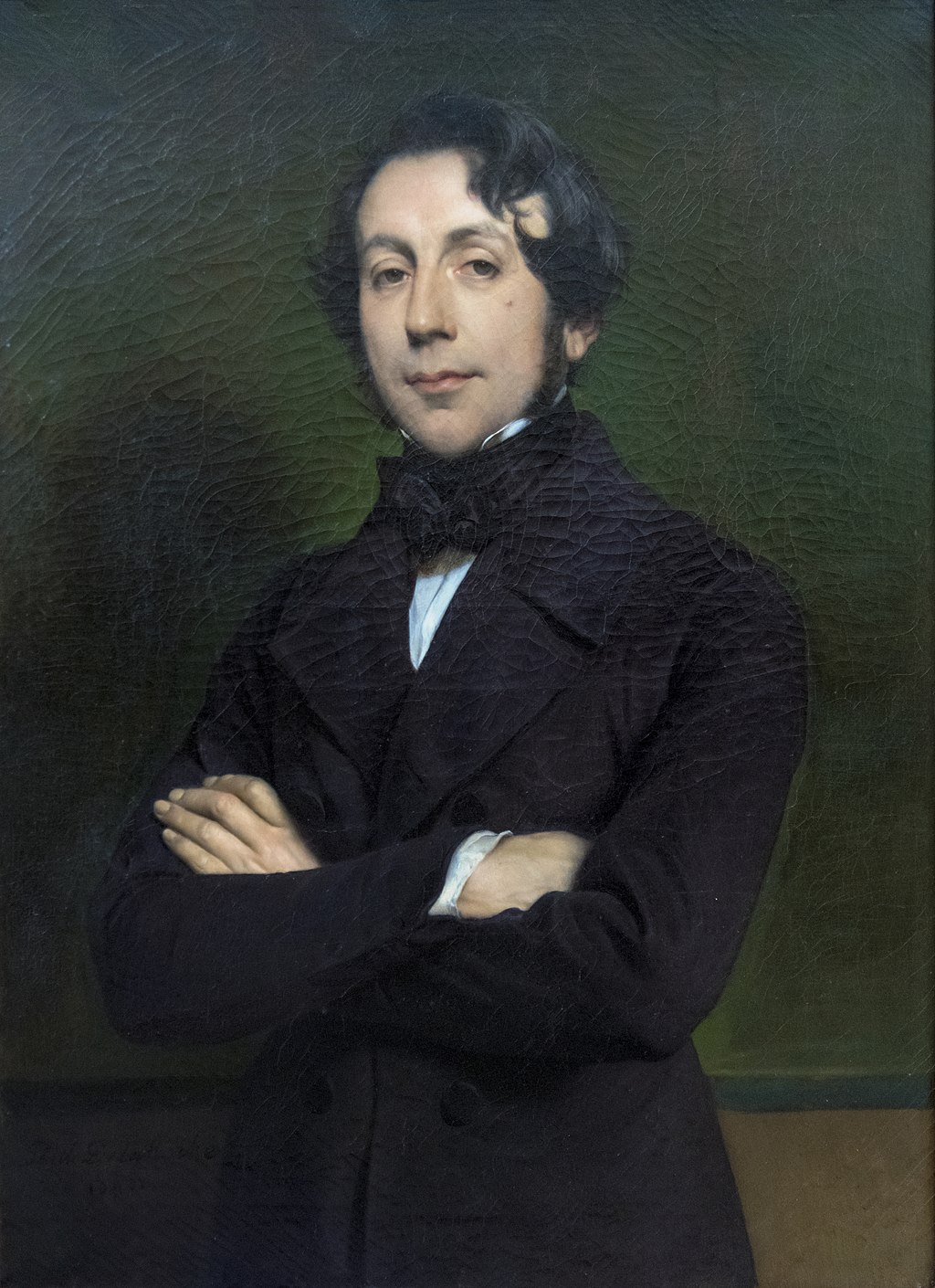

Right: Charles de Rémusat, 1843, by Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It was the morning of Monday, July 26, 1830. Like the Duc d’Orléans and thousands of others across Paris, Rémusat had just learned of the Four Ordinances. But unlike most of those thousands of Parisians, Charles de Rémusat did not spend that Monday waiting to see what was going to happen in response to the king’s coup d’état. Because Rémusat was a journalist — a class of people who were directly impacted by the Four Ordinances, and a class of people with a unique ability to do something about it.

This is The Siècle, Episode 40: The Journalists.

Welcome back, everyone. Today is the first in a series of episodes exploring the aftermath to the Four Ordinances of July 1830 — from the limited and confused perspectives of the people who were actually there. As you’re about to see, Parisian journalists are going to play a massive role in the events to follow.

Before we dive into the narrative, I wanted as always to thank you all for your support. That especially includes the show’s supporters on Patreon, who help support my research for the show. Every supporter who contributes as little as $1 per month receives an ad-free feed of the show, including backers who’ve joined since my last episode: Ethan Rutledge, MJ99, Tom, Sir Paperweight, Fusipon, Kevin Vernia, Claire Hamilton Russell, Amir Latifi, Devereaux Parker, Karsten, Sam Jantz, Drew Corbett, Irina Yeltsova, Guapo Venom, Curtis, Ian Raffaele, Victor, and Fernando López Ojeda. You can find out how to join them and get an ad-free feed at thesiecle.com/support.

The Siècle is a proud member of the Evergreen Podcasts Network.

Now, let’s get back to the story.

Choices

It’s not surprising that France’s newspaper journalists are front and center in the response to the Four Ordinances. As I covered in Episode 39, the Four Ordinances were issued in a newspaper. The First Ordinance imposed sweeping censorship on newspapers, so these reporters and editors weren’t just facing a political threat, they faced the loss of their jobs. More than almost anyone — except perhaps the newly elected deputies who had just had their wins annulled — journalists had a personal stake in what was happening.

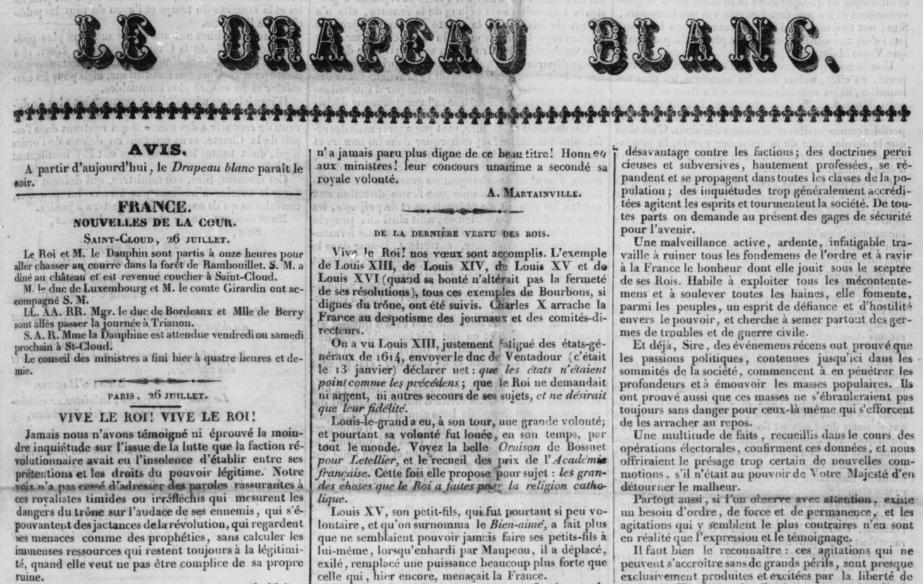

Or at least, opposition journalists did. The opposition represented the majority of the “Fourth Estate” in Restoration France, and ran the most popular papers, but there were ultraroyalist papers with their own stables of writers.2 These Ultra papers cheered the Four Ordinances, such as the Drapeau Blanc’s triumphant cry of “Vive le roi! Vive le roi!” (Or, “long live the king!”) The Drapeau Blanc declared that the Four Ordinances meant the “dawn of a new era for monarchy” and a “new Restoration,” and warned that “resistance would be ‘crushed and punished on the spot.’”3

An excerpt from the July 27, 1830 edition of the Drapeau Blanc ultroyalist newspaper, responding to the Four Ordinances by exulting, “Vive le roi!” Accessed via RetroNews: https://www.retronews.fr/journal/le-drapeau-blanc/27-jul-1830/623/1810391/1.

The more temperate Gazette de France spent less of its front page bragging and more defending the Four Ordinances. It wrote that they were “measures based on the invocation of the Charter” that “men truly attached to representative government” would surely support. Opposition voices would not be “muffled”; there would be two months for “opinions against these legal measures to manifest” before elections for the new Chamber — elections in which the Gazette was sure the opposition would do respectably. The Ordinances were definitely constitutional, and the Charter’s rights remained intact, since “freedom of the press was only suspended” temporarily, not abolished permanently.4

But ultraroyalist journalists could cheer the Four Ordinances in part because they had reason to expect they would be not personally impacted. The First Ordinance banned all newspapers “except when authorized” by the royal government. The Ultra papers all promptly applied for this authorization on July 26, fully expecting it would be granted.5 It was.

There was no optimism among the opposition papers, who presumed they would not be allowed to publish. The question was, what to do about it?

It’s important to keep in mind that while the timing of the Four Ordinances had taken people by surprise, opposition journalists had been expecting something like this for a long time. A few months prior, a rumor that Charles was about to impose censorship had provoked a meeting of journalists at the house of one of the owners of Le Constitutionnel, the largest opposition newspaper. That meeting had agreed on nothing except a general principle that journalists should “resist” censorship, though some of the writers kept talking into the evening about how they might respond.6

More broadly, as I’ve covered on the show, French newspapers had been fighting government censorship for a long time. It had been a constant cat-and-mouse game between the government and the press, and the press had come out on top more than a few times. These papers had a whole range of options. The boldest move was to simply defy the ordinance and publish anyway, which some of these journalists wanted to do — make the government shut them down by force. But this was a gambit with huge potential costs. The First Ordinance let the government seize or even destroy defiant printing presses, and these were extremely expensive machines.7

That didn’t mean these newspapers had to roll over. Under past censorship attempts, French newspapers had sometimes found ways to comply with the letter of the law while still finding a way to get their message out. Perhaps there was some legalistic loophole here that papers could exploit to keep publishing while the politicians found a way to overturn the Four Ordinances? To be sure, the First Ordinance had been drafted specifically to close as many loopholes as possible. But maybe Charles’s incompetent ministers had missed something they could exploit.

My meeting at André’s

So the first order of business for opposition journalists on July 26 was obvious: they needed to meet with a lawyer. And there was a good one on hand: the famed litigator André Dupin was the house attorney for Le Constitutionnel as well as an opposition deputy and member of the 221. As news of the Four Ordinances spread Monday morning among opposition journalists, so did news of a meeting that day at Dupin’s office.8

So the first order of business for opposition journalists on July 26 was obvious: they needed to meet with a lawyer. And there was a good one on hand: the famed litigator André Dupin was the house attorney for Le Constitutionnel as well as an opposition deputy and member of the 221. As news of the Four Ordinances spread Monday morning among opposition journalists, so did news of a meeting that day at Dupin’s office.8

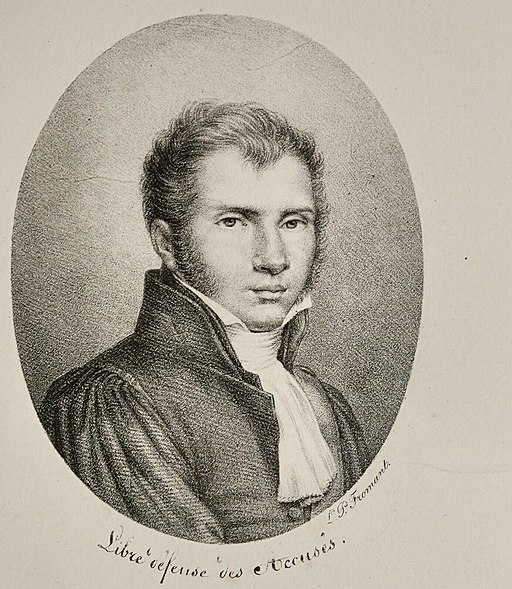

Left: André Dupin, a famous liberal lawyer and politician often called “Dupin aîné,” or “Dupin the Elder,” to distinguish him from his brother, the mathematician Charles Dupin, by L.P. Fromant, circa 1815. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Rémusat was one of the writers who heard of the meeting with Dupin and resolved to show up. Before leaving, though, Rémusat took one more important step — he sent a copy of the Moniteur along with a personal note to his wife’s grandfather, who was currently relaxing at his country estate. The note said to read the paper and then hurry to Paris, because a situation this dramatic absolutely called for the presence of his grandfather-in-law: Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.9

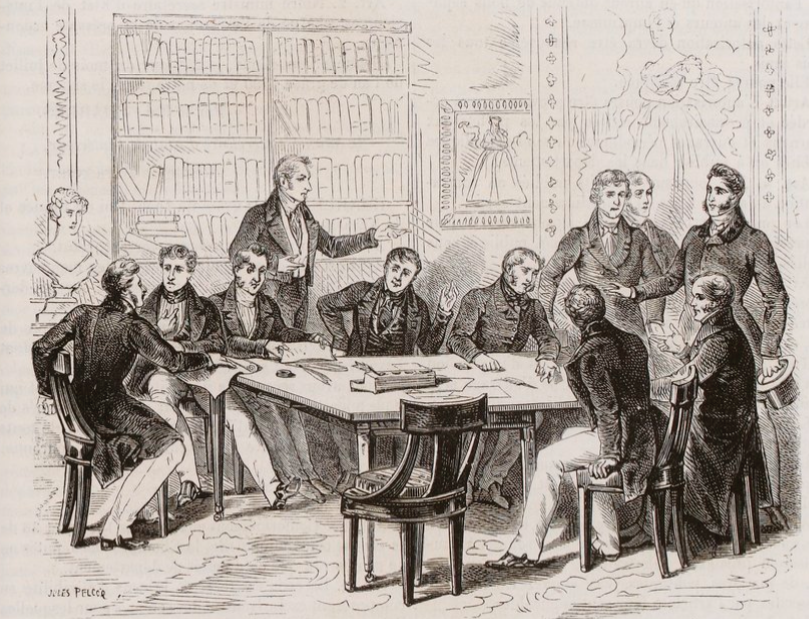

When the journalists arrived in Dupin’s office, everyone was a little confused at first. Dupin, who had expected a consultation with his clients, the owners of Le Constitutionnel, instead found a dozen or so agitated writers hanging out in his office. “No one really knew why we were here,” recalled Rémusat later. Once that was settled out, Dupin assured everyone present that the Four Ordinances were extremely illegal, and that journalists “had the right, even the duty,” to resist. This statement drew widespread acclaim. Then everyone sat there awkwardly, waiting for Dupin to say more — like, say, advice on what to do next. When he didn’t, the journalists started making suggestions themselves, like drawing up a joint protest on the spot. At this point, Dupin became visibly upset and told them that he could not permit a political meeting to take place in his law office. As everyone walked out, one of the journalists present gave an exasperated sigh: “Lawyers!”10

What happened next proceeded on several tracks. Publishers had to decide what to do — challenge the ordinances or comply with them? The two biggest opposition papers, the Constitutionnel and the Journal des Débats, were caught in the middle. Unwilling to either comply or resist, they simply chose not to publish an edition for Tuesday, July 27 — while also declining to acknowledge the validity of the Four Ordinances by asking for permission. (Dupin had been firm on that point in the meeting, saying that “any newspaper that submits to requesting authorization would not deserve to keep a single subscriber in France!”)11 Several other opposition papers filed lawsuits challenging the ordinances, which began working their way through the legal system.12

The Protest of the Forty-Four

But many younger journalists were not inclined to wait for the courts. So when the meeting at Dupin’s office broke up, many of its attendees headed over to the nearby offices of another newspaper where they expected — and found — an ongoing discussion about how to resist.

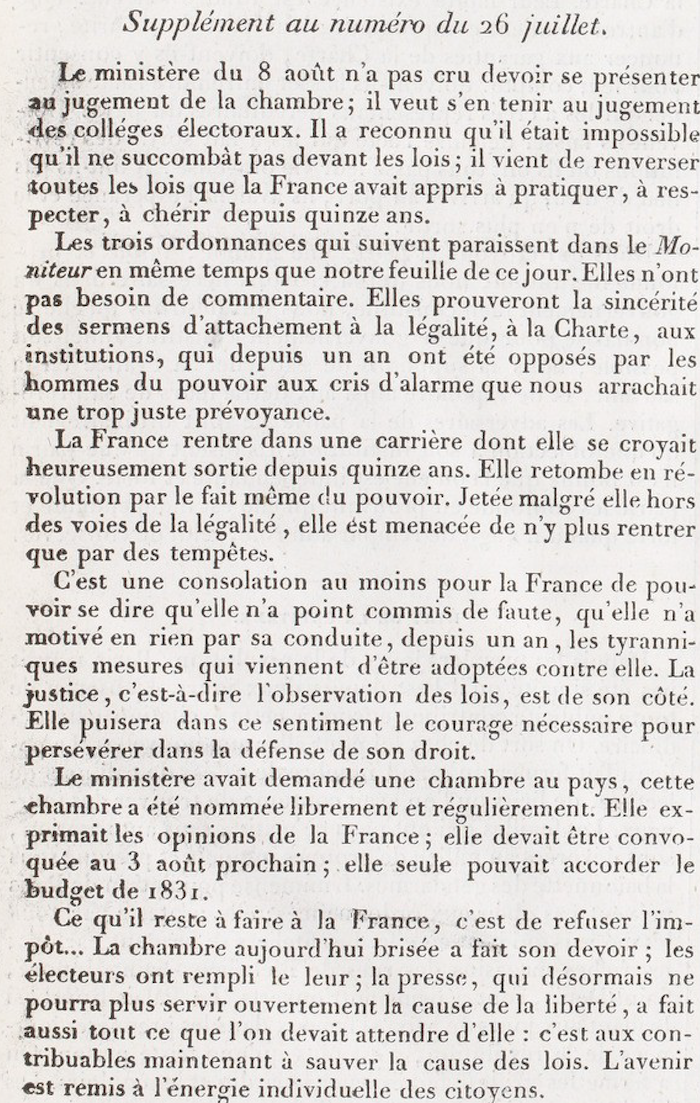

This was the offices of the National, a small but fiery opposition newspaper that had already taken a crucial step to resisting the ordinances: it had rushed out a supplemental issue midday Monday, reprinting the ordinances from the Moniteur and adding a brief commentary, that France “falls back into revolution by the act of government itself.” But by invoking revolution, the National on July 26 did not call for people to take to the streets. Instead, it called to implement the plan of civil disobedience that liberals had been talking about for months: a tax strike. By massively withholding their taxes, the opposition could starve the government of money and — like in 1789 — force a bankrupt government to yield.13

This was the offices of the National, a small but fiery opposition newspaper that had already taken a crucial step to resisting the ordinances: it had rushed out a supplemental issue midday Monday, reprinting the ordinances from the Moniteur and adding a brief commentary, that France “falls back into revolution by the act of government itself.” But by invoking revolution, the National on July 26 did not call for people to take to the streets. Instead, it called to implement the plan of civil disobedience that liberals had been talking about for months: a tax strike. By massively withholding their taxes, the opposition could starve the government of money and — like in 1789 — force a bankrupt government to yield.13

Right: The text of the declaration printed in the supplemental July 26 edition of Le National. Image taken from a composite edition printed July 31, 1830, containing content dated July 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Was this enough? As a manifesto, this July 26 supplemental had a few shortcomings. As befit its rushed status, it was short — just six paragraphs. And as a piece of resistance, it had the singular drawback of possibly not being illegal!

You see, while Charles had signed the Four Ordinances on Sunday, July 25, and published them on the morning of July 26, the ordinances had been drafted in secrecy. And among those who hadn’t been in the loop was Jean Henri Mangin, the police prefect. It was Mangin’s job to enforce the First Ordinance. And Mangin didn’t issue his order enforcing censorship until 5 p.m. on Monday!14

But anything published on Tuesday, July 27, would definitely be illegal. Despite the risk to themselves and their newspapers, the journalists in the National offices quickly agreed they needed to make a bolder stand, rather than wait for lawsuits or a tax strike to bear fruit. One participant, Adolphe Thiers of the National, spoke enthusiastically in favor of this plan — and as historian David Pinkney put it, “the practices of citizen’s meetings in 1830 being no different than those of today, the gathering immediately charged [Thiers] with the drawing up of the protest.”15

But anything published on Tuesday, July 27, would definitely be illegal. Despite the risk to themselves and their newspapers, the journalists in the National offices quickly agreed they needed to make a bolder stand, rather than wait for lawsuits or a tax strike to bear fruit. One participant, Adolphe Thiers of the National, spoke enthusiastically in favor of this plan — and as historian David Pinkney put it, “the practices of citizen’s meetings in 1830 being no different than those of today, the gathering immediately charged [Thiers] with the drawing up of the protest.”15

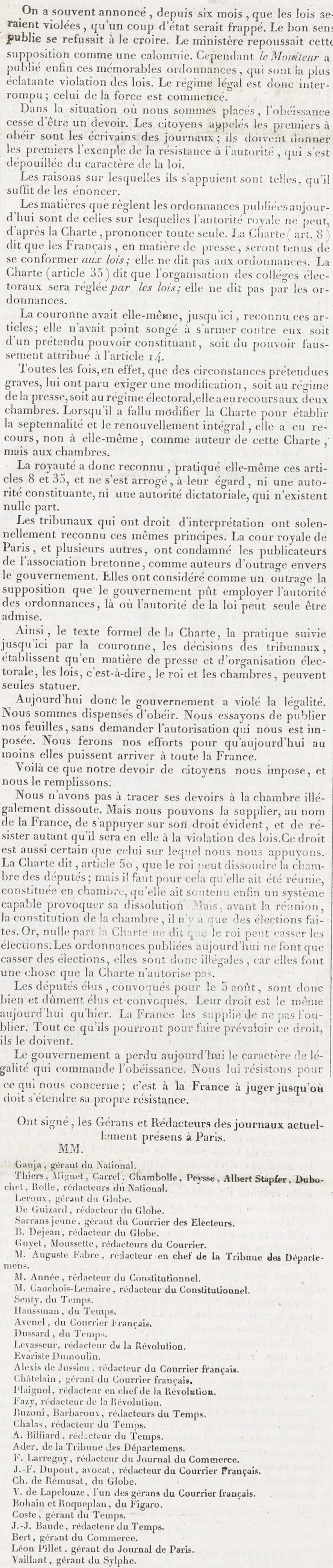

Right: A composite image showing the text of the Protest of the 44. Image taken from a composite edition printed July 31, 1830, containing content dated July 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

While Thiers was in a back room drafting his declaration, two new visitors arrived: not journalists, but deputies from the newly elected chamber that Charles had just dissolved. These two men brought news, but it wasn’t encouraging. They had just come from a gathering of a half-dozen opposition deputies, who had all agreed the ordinances were illegal — but thought they didn’t have the standing to oppose them. For one thing, they were just a half-dozen deputies, not a majority of the chamber. For another, they arguably weren’t even deputies. Back in May, Charles had dissolved the old Chamber of Deputies, and that was perfectly legal — no one disputed that. The newly elected Chamber — the one Charles had tried to preemptively dissolve in the Second Ordinance — wasn’t legally set to convene until August 3. On that date the men would be deputies again, whatever the Second Ordinance said, and then they could join the entire rightfully elected Chamber to organize resistance.16

This kind of legalistic caution was not what the assembled writers had in mind. So the initiative would pass to the journalists, not the politicians.

When he finished, Thiers’s protest was approved with only minor changes. The biggest debate was over how the manifesto should be signed. Some more cautious writers argued for leaving it unsigned — a general protest of journalists, collectively. Others said they were happy to sign for themselves, but didn’t feel like they could sign on behalf of their newspapers. A few writers walked out. Finally Rémusat broke the deadlock by walking forward and signing his own name and that of his newspaper, the Globe. One after another followed, until 44 journalists representing a dozen newspapers had signed the document.17

This protest thus became dubbed the “Protest of the Forty-Four.” By that evening, it would be circulating around Paris in the form of handbills. The next day, it would illegally appear in four newspapers willing and able to defy the censorship. And it generally didn’t mince words. It called the Four Ordinances “a most flagrant violation of the laws” — that much everyone in the opposition agreed on — but then kept going: “the rule of law is thus broken; that of force has begun,” the Protest read:

In the situation in which we are placed, obedience ceases to be a duty. The citizens first called upon to obey are the writers of the newspapers; they should set the first example of resistance to authority which has divested itself of the character of law…

Today, the government has violated legality. We are called to obey. We are going to publish our newspapers, without asking for the authorization which is imposed upon us…

We do not have to point out its duties to the illegally dissolved Chamber. But we can ask it, in the name of France, to seize its obvious right, and to resist, so far as it can, the violation of the laws…

The government has lost today the character of legality which commands obedience. We resist it for that which concerns us; it is up to France to judge to what point she should extend her own resistance.18

Jules Pelcoq, “Révolution de 1830. — Protestation des journalistes,” in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Printer error

With the protest written and signed, it only remained to be distributed. Not all of the signatories had papers willing to defy the Ordinances and publish — we’ve already seen the Constitutionnel take a pass.

Others were willing to publish, but found that their printers balked. One such example was Auguste Fabre, the editor of the republican newspaper the Tribune des départements. As one of the most radical writers in the capital, Fabre was eager to defy the ordinances. But doing so could lead to police smashing up the printing press, and the printer was unwilling to risk his expensive machine. The printer said he’d be happy to print the defiant issue of the Tribune — but only if Fabre put up a massive 200,000-franc bond to cover the cost of the press. This was many times more money than a typical Frenchman earned in a year, and Fabre couldn’t come up with it. He spent the day begging other opposition papers to print the Tribune for him — with no luck.19

Rémusat ran into a similar difficulty with the printer for the Globe. “We found him very disturbed,” Rémusat wrote. “He did not hide from us that he would not do anything that could cause him to lose his printer’s license.” But unlike the republican Fabre, Charles de Rémusat was a count. In his memoirs, Rémusat claims he asked his printer how much the press was worth — and then offered to guarantee its 80,000-franc value out of his own personal fortune.20

As it happened, Rémusat’s printer was unwilling to publish the offending issue even with this financial guarantee, but these contrasting stories highlight the unequal resources that different parts of the French opposition were bringing to their fight with the king. Instead, Rémusat worked connections late at night until he finally found a printer willing to bring the Globe to press.21

The die was now cast. Would the people listen to this call for revolution? On Monday afternoon, there was little sign of popular unrest. The naval minister, d’Haussez, walked the streets of Paris and “saw no unusual gatherings of people, not even around posted copies of the day’s Moniteur.” An opposition journalist observed the same calm and threw up his hands: “What can be done with a nation of shopkeepers?” he exclaimed.22 Without the people, the journalists might be on their own. As Thiers and Rémusat sat in a café that evening, Thiers remarked that within 24 hours they could be locked up in the prison fortress of Vincennes.23 And they had reason to worry. As soon as the police prefect Mangin saw the printed Protest, he issued arrest warrants for all 44 journalists brave or foolish enough to sign it.24

But we’re not going to end this week with the police hunting down Thiers, Rémusat, and the other 42 dissident writers. Because before the police could get around to that, they had more pressing matters to deal with.

Malice at the Palace

On that Monday evening, police descended on the Palais Royal, the palace-turned-shopping-center in the heart of Paris. The Palais Royal’s owner, the Duc d’Orléans, was absent. But Louis-Philippe wasn’t the target. Instead it was a reading room owned by an “eccentric old Ultra,” the Marquis de Chabannes. Chabannes was an elderly conservative who used his reading room to distribute his own bad poetry. His establishment was quite popular — not because of his doggerel, but because Chabannes had fallen out with Polignac and so turned his reading room into a den of anti-Polignac papers.25

On that Monday evening, police descended on the Palais Royal, the palace-turned-shopping-center in the heart of Paris. The Palais Royal’s owner, the Duc d’Orléans, was absent. But Louis-Philippe wasn’t the target. Instead it was a reading room owned by an “eccentric old Ultra,” the Marquis de Chabannes. Chabannes was an elderly conservative who used his reading room to distribute his own bad poetry. His establishment was quite popular — not because of his doggerel, but because Chabannes had fallen out with Polignac and so turned his reading room into a den of anti-Polignac papers.25

Right: Jean-Baptiste de Chabannes, Marquis de Chabannes. Artist unknown, 1815 or later. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Reading rooms like Chabannes’s were one of the most common ways ordinary Parisians accessed the city’s newspapers. Subscription fees were out of the reach of the city’s working classes, but many people could afford to pay for access to a reading room and read the day’s papers.26

So when Mangin’s men arrived to shut down the reading rooms, the Marquis de Chabannes was in high dudgeon — and the assembled crowd backed him up. The old aristocrat refused to allow the police into his shop, and then caused a huge scene that roused the people to his defense. Under the marquis’s encouragement, the patrons of the Palais-Royal pelted the police with hurled objects until they were driven away.27

The journalists of Paris had, on the afternoon of July 26, taken the first acts of resistance to the Four Ordinances. That evening, the people of Paris had risen in defense of their newspapers to physical resistance. But was it a fluke? Next episode, we’ll shift our focus from the journalists of Paris and see what exactly a nation of shopkeepers can do. Join me next time for Episode 41: The People.

-

Charles de Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, tome II: La Restauration ultra-royaliste, la Révolution de Juillet (1820-1832), ed. Charles-H. Pouthas (Paris: Plon, 1959), 309-10. ↩

-

Daniel L. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827-30 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 30-5. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 224. ↩

-

La Gazette de France, July 27, 1830. Accessed via Bibliothèque Nationale de France: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k44857035/. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 445. ↩

-

Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 310-1. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 225. ↩

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 84. ↩

-

Mike Duncan, Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution (New York: Public Affairs, 2021) 408, Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 310. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 84-5. Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 311-2. André-Marie-Jean-Jacques Dupin, Mémoires de M. Dupin, Tome Deuxième: Carrière Politique — Souvenirs Parlementaires. M. Dupin Député, Ministre, Président, 1827 à 1833 (Paris: Typographie Henri Plon, 1856), 137-8. I took some liberties translating the final sigh. Literally translated, as related by Rémusat, was “Oh, the lawyers, the lawyers.” In his memoirs — written with a somewhat defensive tone suggesting years of defending himself against accusations of timidity on this occasion — Dupin says he drew a legalistic distinction about his various roles: “Here [in this office] I am not a deputy, I am a lawyer.”. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 225. Dupin, Mémoires de M. Dupin, 137. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 225-6. ↩

-

I discussed the National and the idea of a tax strike in Episode 34. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 227. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 86. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 87. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 86-8. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 227. Note that Pinkney incorrectly claims the writers signed for 11 newspapers. Rader cites 12 — the Journal de Paris is the one Pinkney omits — and the original document backs Rader by listen 12 papers, including the Journal de Paris. National SUPPLEMENTAL. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 266-7. J.P.T. Bury and R.P. Tombs, Thiers, 1797-1877: A Political Life (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1986), 28-9. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 225. ↩

-

Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 313. ↩

-

Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 316, 318. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 82. Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 316. Note: The original version of this script, and the audio release, incorrectly described Haussez as the interior minister. Corrected July 1, 2025. ↩

-

Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 319. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 227. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 228. ↩

-

Irene Collins, The Government and the Newspaper Press in France, 1814-1881 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), 19-20, 28-29. Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, 293-4. . ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 228 ↩