Episode 42: Marmont

General Auguste de Marmont, Duke of Ragusa and Marshal of France, was having a very bad day.

To be fair, a lot of Parisians were having bad days on July 28, 1830 — not just Marmont. But if that was supposed to make him feel any better, it wasn’t working.

Here he was, one of the most distinguished military men of his age, ordered to kill his own people, in defense of laws he opposed — and he was losing.

Worst of all, Marmont wasn’t even supposed to be here. He would have been safely at home — if it weren’t for those darn sheep.

This is The Siècle, Episode 42: Marmont.

Welcome back, everyone! Thank you for following along as I relate these increasingly exciting events in July 1830. This is one of my favorite episodes of the show so far, so I hope you like listening to it half as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Welcome back, everyone! Thank you for following along as I relate these increasingly exciting events in July 1830. This is one of my favorite episodes of the show so far, so I hope you like listening to it half as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Before I get going, I wanted to let you know about a cool new development: I’m now selling merch for The Siècle! If you’ve ever wanted to get the podcast’s logo on a sticker, tote bag, or t-shirt, now you can! I’ve also created a few other pieces of work, including my personal favorite: a coffee mug featuring King Louis XVIII and the slogan, “I prefer Bourbon.” Visit thesiecle.com/support to check it out, or a link directly in the show notes.

Right: Me, showing off some of the new merch for The Siècle.

I also owe huge thanks to a ton of you who’ve generously begun supporting The Siècle since the last episode: Glenn Hoffman, Patrick Gappo, Bob Evans, Jack Beanland, Delmar Reffett, Nopetk, Mike Andrzejewski, Ben Fischer, Owen Smigelski, Martin Mella, Bruno Baretta, Rob Remar, Gustafson, Charles Haycox, Larry Ayre, Nick Boll, DakAscot, Donald Eckler and Hazem Eseifan. Every single one of them gets access to an ad-free feed of the show, and so can you for just a couple bucks a month. Find out how to join them at thesiecle.com/support.

The show is also supported by Evergreen Podcasts, where The Siècle is a proud member.

Finally, if you didn’t check out the most recent bonus episode, Supplemental 21, you should! It was a tremendously fun discussion with two other French history podcasters: Will Clark of Grey History: The French Revolution, and Everett Rummage of Age of Napoleon. Each of us nominated people from the French Revolution, Napoleonic, and Restoration periods for prizes in categories such as Corruption, Disappointment, and Eloquence.

But I do have a bit of a correction to make. In that episode, I nominated Martignac for the gold medal in Misfortune. That was a deliberate lie on my part, because of the timing of when that episode came out. The actual person I would nominate for achievement in Misfortune is the tragic star of today’s episode: Marshal Auguste de Marmont. Buckle up, because by the time we’re done, I think you’ll agree.

An unusual appointment

Marshal Marmont was appointed commander of the military district of Paris on July 25, 1830 — the day that King Charles X signed the Four Ordinances.1

Marshal Marmont was appointed commander of the military district of Paris on July 25, 1830 — the day that King Charles X signed the Four Ordinances.1

Left: Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin, portrait of Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont, Marshal of France, 1837. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This was an unusual appointment in several ways. For one thing, you might recall from Episode 38 that Charles’s government had an experienced general in it: Minister of War Louis Auguste de Bourmont. There’s no relation between Bourmont and Marmont, despite their very similar names — and no love lost between them, either. A loyal ultraroyalist, Bourmont had been appointed precisely because he was seen as willing to fight on behalf of the Bourbons. Charles’s son, the Duc d’Angoulême, said that “Bourmont will mount a horse with me, if this step becomes necessary.”2 But in late July 1830, when the Bourbons needed a proverbial “man on horseback,” Bourmont was not in Paris — he was across the Mediterranean Sea in Algiers, having conquered the city for France a few weeks earlier. This meant Bourmont wasn’t able to supervise the defense of Paris. It also meant France’s experienced war minister wasn’t around to coordinate military affairs. In Bourmont’s place as Acting Minister of War was prime minister Jules de Polignac, who had no military experience.3

Marmont’s appointment on July 25 to the command of Paris’s military district was also unusual because no one thought to tell him he was now in command. It appears that Polignac didn’t expect any trouble — Marmont was just a contingency plan for the unlikely event that military support was needed. Oblivious, Marmont that day granted leave to his chief of staff to take a vacation. Now, lots of people were kept in the dark on Sunday, July 25, with the Polignac ministry’s drive for secrecy. But Marmont continued to be oblivious the next day, as the Paris police began preparing to enforce the ordinances. On Monday afternoon, still oblivious while Adolphe Thiers was drafting the Protest of the Forty-Four, Marmont was attending a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences.4

Another way that Marmont was an unusual choice to defend Paris was that unlike Bourmont, Marmont was definitely not an ultraroyalist. He was a voting member of the Chamber of Peers, and his sympathies were decidedly with the liberal opposition. “The lunatics, as I foresaw, have pushed things to the extreme!” Marmont declared on Monday afternoon. But like Polignac and leading opposition politicians, Marmont didn’t think things would turn violent. “Resistance,” he told a friend Monday morning, “will be entirely constitutional and moral: they will refuse to pay the taxes and the Government will collapse if the Ministry is not driven out — for which latter event I dare not hope.” It was possible that there could be riots, Marmont said, but if there were, they would surely take place in September, when the new elections called for by the Four Ordinances would take place. Marmont’s period on active duty ended August 31, and he declared his intention to leave Paris the very day after, so he would be safely out of the way in Italy if any violence happened.5

These illusions were quickly shattered. On Tuesday morning, Marmont was attending the king’s court at the suburban palace of Saint-Cloud when he was pulled aside and told the king wanted to see him. At 11:30 a.m., Charles told Marmont: “It appears that there is some concern for the tranquility of Paris. Go there, take command, and see Prince Polignac on your way. If all is in order in the evening, you may return to Saint-Cloud.”6

Having finally been told he was in command, Marmont reacted briskly. Accompanied by an aide, he left immediately for Paris, met Polignac for a briefing at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and by 1 p.m. was installed at his command post in the Tuileries Palace.7

Just a few hours after that, as we saw last episode, members of the Royal Guards would open fire on rioters. Marmont immediately took over from the beleaguered police and guardsmen, quickly deploying his regiments and battalions throughout the city.8 It was the kind of vigorous action you might expect from Marmont, a man with decades of military experience in some of the fiercest fighting of the age.

But many Parisians didn’t think of Marmont’s victories when they heard he was the man appointed to suppress them. They remembered one of his defeats. And so, to understand why so many Parisians were upset at Marmont’s appointment, we’re going to need to do some backstory.

Rise of a Marshal

Auguste de Marmont was born in July 1774, the son of a minor noble. He joined the army at age 16, in the early years of the French Revolution, and soon moved up the ranks. In September 1792, Marmont was given a promotion to lieutenant in the 1st Foot Artillery Regiment. It was an important milestone, not just for the promotion, but also because of a fellow officer in the 1st Artillery: Captain Napoleon Bonaparte.9

Auguste de Marmont was born in July 1774, the son of a minor noble. He joined the army at age 16, in the early years of the French Revolution, and soon moved up the ranks. In September 1792, Marmont was given a promotion to lieutenant in the 1st Foot Artillery Regiment. It was an important milestone, not just for the promotion, but also because of a fellow officer in the 1st Artillery: Captain Napoleon Bonaparte.9

Left: Georges Rouget, portrait of Lt. Auguste de Marmont in 1792, painted 1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Marmont and Bonaparte met at the Siege of Toulon, and quickly became friends. This would pay swift dividends for Marmont as his friend’s star began to rise. In 1796, Bonaparte chose Marmont as one of his aides for the Italian campaign, and promoted him to artillery major. There Marmont distinguished himself, coordinating artillery fire, leading frontal charges, and capturing enemy batteries. More promotions followed, as did an appointment to accompany Bonaparte on the French invasion of Egypt. There, Bonaparte appointed his trusted aide to administer the city of Alexandria, where he enforced order and also imposed civil reforms. As we’ll see, it was in this role as a military governor that Marmont was perhaps most adept.10

When Bonaparte abandoned Egypt and slipped back to France in 1799, Marmont was one of the handful of officers chosen to accompany him; the rest of the army was trapped by the British Navy and ultimately surrendered. Back in France, Marmont supported Bonaparte when he overthrew the French Directory in the 1799 Coup of 18 Brumaire.11

More appointments followed: a seat on the French Council of State; Bonaparte’s commander of artillery for his 1800 Italian campaign; inspector-general of artillery in 1802; commander-in-chief of artillery for the new Grande Armée in 1803. But when the newly crowned Emperor Napoleon announced his first round of Marshals of the Empire in May 1804, Marmont was not among them. Napoleon told the 29-year-old Marmont that he was still too young, but Marmont felt he deserved a marshal’s baton and seethed at the slight.12

An unexpected promotion came in 1806, when Napoleon appointed Marmont as governor-general of Dalmatia, the newly conquered territories along the Adriatic coast in what is today mostly Croatia. Marmont enforced French control with an iron fist — my source uses the euphemism “stern” to describe his rule — but successfully maintained French control of the sensitive region. He also “built roads, established industries, increased trade, and founded schools,” while also instituting legal reforms. Years later, when the Austrian Empire had control of the region, the Austrian emperor remarked that, “It is a great pity that… Marmont was not two or three years longer in Dalmatia.”13

Below: Jacques Luc Barbier Walbonne, “Equestrian portrait of Marshal Marmont,” circa 1810. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

During his period as governor-general, Marmont was given a noble title: the Duke of Ragusa, after the Dalmatian city today known as Dubrovnik. In 1809, Marmont joined Napoleon at the Battle of Wagram and finally received the appointment as a Marshal that he felt he deserved. But any elation Marmont might have felt was tempered by the ruthless way Napoleon gave it, telling his newest marshal that:

During his period as governor-general, Marmont was given a noble title: the Duke of Ragusa, after the Dalmatian city today known as Dubrovnik. In 1809, Marmont joined Napoleon at the Battle of Wagram and finally received the appointment as a Marshal that he felt he deserved. But any elation Marmont might have felt was tempered by the ruthless way Napoleon gave it, telling his newest marshal that:

I am afraid I have incurred the reproach of listening rather to my affection than to your right to this distinction. You have plenty of intelligence, but there are needed… war qualities in which you are still lacking, and which you must work to acquire. Between ourselves, you have not yet done enough to justify entirely my choice.14

Marshal Marmont’s chance to prove Napoleon wrong came in 1811, when he was appointed to command the struggling French army in Spain. Facing off against an Anglo-Portuguese army under the Duke of Wellington, Marmont at first fought cautiously and refused to be drawn into a battle of Wellington’s choosing. But when the fighting finally opened at Salamanca on July 22, 1812, Marmont let himself be misled by bad intelligence, and failed to stop one of his divisions from drifting out of alignment. As Wellington charged the exposed French flank, Marmont was badly wounded by an artillery shell and carried from the field. Without its wounded commander, Marmont’s former army suffered a “resounding defeat.”15

Napoleon never forgave Marmont for this defeat, which seemed to confirm the emperor’s judgment of Marmont’s limitations. “Let Marshal Marmont know how indignant I am with his inexplicable conduct,” Napoleon said after receiving a report while deep into his 1812 invasion of Russia.16

Napoleon never forgave Marmont for this defeat, which seemed to confirm the emperor’s judgment of Marmont’s limitations. “Let Marshal Marmont know how indignant I am with his inexplicable conduct,” Napoleon said after receiving a report while deep into his 1812 invasion of Russia.16

The two-decade-long friendship between these two military men was basically over. As he recovered from his wounds in Paris, Marmont began to make new friends: civilians, sophisticated salon-goers and rich businessmen, people whose bourgeois liberalism was increasingly hostile to the declining Napoleonic Empire. It was these friends, and not Napoleon Bonaparte, who would be around Marmont in March 1814 when he made a fateful decision.17

Above: Gregory Fremont-Barnes, ed., map of the Battle of Salamanca, 2006. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Betrayal

Defeats suffered by Marmont and other French generals in Spain, combined with Napoleon’s infamous 1812 disaster in Russia, marked the beginning of the end for the French Empire. There were moments where victory might have been salvaged after that, but by early spring of 1814 the Allies had invaded France itself. Napoleon, fighting on home ground, won series of lightning victories that seemed, for a moment, like they might salvage the war. But Napoleon’s victories were won in eastern France, and several days march away, other Allied armies were closing in on Paris. Napoleon began racing his forces west, but the city needed to hold out long enough for him to arrive. Which put a lot of pressure on the general in command of Paris’s defenses in March 1814, Auguste de Marmont.18

Marmont and his fellow marshal Édouard Mortier beat back an Allied attack in the Paris suburbs on the morning of March 30. Marmont fought hard and at the front, taking a wound to his arm and emerging from the battle covered in mud and blood. But his heart — like the hearts of many other French leaders in Paris — wasn’t in the fight any more. Napoleon’s brother Joseph, acting as regent, gave permission to the marshals to negotiate a ceasefire, then fled the city.19

Above: Horace Vernet, “The Barrier of Clichy: Defense of Paris, March 30, 1814,” 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. This painting shows Marshal Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey giving orders to Col. Claude Odiot of the National Guard, who commissioned the painting.

For his part, Marmont was convinced there was no point in further fighting. Doing so would only kill more of his soldiers — and possibly the civilians of Paris, if the Allied forces sacked the city like they threatened to do. But even if Marmont had been okay with casualties, he no longer agreed with the cause. As he relates it in his memoirs, during the ceasefire negotiations on the night of March 30, there was a meeting at his headquarters with a “great number of my friends,” including Paris civilians. Everyone, Marmont writes, “agreed on one point: that the fall of Napoleon was the only way to safety.” He claims the Paris banker Jacques Laffitte was the “most energetic voice” in favor of Louis XVIII and the Bourbons as Napoleon’s replacement. “With written guarantees, with a political system establishing our rights, what is there to fear?” Laffitte allegedly argued.20

Sixteen years later, when a Bourbon monarch tried to rewrite those written guarantees and that political system, Laffitte had emerged as a leading opposition voice. And Marmont was the man tasked with defending the same city he had once surrendered.

Because around 2 a.m. on March 31, 1814, Marshal Marmont agreed to a ceasefire with the Allied armies. The French forces would stop fighting and be allowed to withdraw peacefully, leaving Paris open to Allied occupation. Napoleon at this time was just 14 miles away with the main French field army. When news came of the city’s surrender, Napoleon cried out, “Had I arrived sooner, all would have been saved,” and sat with his head in his hands for a quarter-hour. The emperor wanted to march on Paris anyway, but was persuaded not to by his other generals.21

This ceasefire saved Marmont’s army. It saved the city of Paris, whose civil leaders welcomed the Allies with open arms and avoided a sack. And it also saved Marmont’s military career — the restored King Louis XVIII retained Marmont and the other Napoleonic marshals in their positions, and Marmont was given honorary command of a company of the king’s bodyguards.22

But the ceasefire destroyed Marmont’s reputation forever. Napoleon saw to that, a final bit of revenge on his onetime friend. “The ungrateful wretch, he will be more unhappy than me,” Napoleon said, and went on to complain about Marmont’s “treachery” for the rest of his life. If not for Marmont’s betrayal, Napoleon continued to insist in his memoirs and conversations, he might have salvaged the war. And this narrative took hold, especially among people sympathetic to Napoleon. Marmont’s title, the Duke of Ragusa, was adopted into a new French noun, “ragusard,” meaning traitor.23

The passage of 16 years had not erased this infamy. One testimony to this comes from the eminent astronomer François Arago, who became perhaps Marmont’s closest friend. But Arago admitted in 1830 most Parisians did not share his fond view of the marshal — and that even he had to overcome some initial prejudice: “As concerns the events of 1814,” Arago said, “I held the opinion that — unfortunately for his reputation — is so generally held among the public.”24

The mere existence of the Four Ordinances was devastating for Marmont, whose justification for his 1814 surrender was that the Bourbons would guarantee French liberties. As another friend, the Comtesse de Boigne, told him on Monday, July 26: “You say that you were obliged to sacrifice yourself in order to obtain liberal institutions for the country. Where are those institutions now?”25

Above: Unknown artist, “The Culmination of the Reign of Alexander I: Marshal Marmont Hands Over the keys of Paris to the Russian Emperor, Tsar Alexander I,” circa 1814. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Marmont’s army

Traitor, hypocrite, sellout — that’s what Parisians thought of Marmont before he sent soldiers into the streets to kill them. Because much as he would have preferred not to, Marmont obeyed his orders and began deploying the French Army to put down the revolt. Regiments and battalions marched out of their barracks to take up strategic locations, including around the royal palace and on the wide boulevards that encircled central Paris.26

Marmont had at his disposal somewhere around 10,000 to 11,000 men. This included approximately 3,800 infantry and 800 cavalry from the Royal Guard, 4,400 to 5,400 infantry of the regular army along with some cannons, and around 1,500 military police from the gendarmes: 600 mounted, around 900 on foot. Two of the Royal Guard regiments weren’t French at all, but rather mercenaries from Switzerland — heirs to a long tradition of Swiss Guards serving the French kings. 27

Now, 10,000 soldiers is simultaneously a lot of men and not very many men. It is, for example, considerably fewer men than the 25,000 who were in Paris in July 1789, when crowds successfully stormed the Bastille.28 It’s also fewer soldiers than should have been in Paris in 1830. Many French soldiers were in Algiers — including the best and most reliable units of the French Army. But even accounting for that army, the garrison was under-strength. Confident that the city was quiet, the Polignac government had deployed thousands of soldiers from the Paris garrison to other parts of the country. In Episode 38 I discussed how there had been a spate of mysterious fires in western France in early 1830; two regiments of the Royal Guard had been sent from Paris to keep order there.29 Other units from nearby Paris had been sent to northern France, because the Polignac ministry had intelligence that suggested a revolution was possible in Belgium. As we will eventually see, this intelligence wasn’t wrong — Belgium was on the verge of a revolution in the summer of 1830 — but it’s deeply ironic that Polignac foresaw unrest in Belgium more clearly than he did in his own capital.30 The net impact was to weaken the Paris garrison even further.

Meanwhile, because of the drive to keep the Four Ordinances secret, Polignac had not moved any extra troops from rural France into Paris. This is in contrast to what happened ten years earlier, in the crisis of 1820, when parliamentary disputes swelled into unrest on the streets. (I covered this in Episode 15.) At that time Louis XVIII and his prime minister, the Duc de Richelieu, summoned thousands of soldiers from garrisons near Paris into the city to successfully defend the government. Polignac did none of that — not even after the Ordinances were published on Monday and the need for secrecy was gone. “As Minister of War I have taken all measures and I promise you that they are well taken,” he blithely assured the worried Austrian ambassador.31

So Marmont’s 10,000 men posed a formidable force. But they were up against tens of thousands of Parisians — the exact number is impossible to determine — who went into revolt after the Four Ordinances. In an open field, Marmont’s trained regulars would have obliterated the civilians. But fighting in the winding streets of central Paris was another matter — especially once the barricades came into the picture. Marmont couldn’t kill all the rebels even if he had wanted to — his path to victory was to use his superior firepower to cow the civilians into returning home. It was going to be a battle of morale.

The battlefield

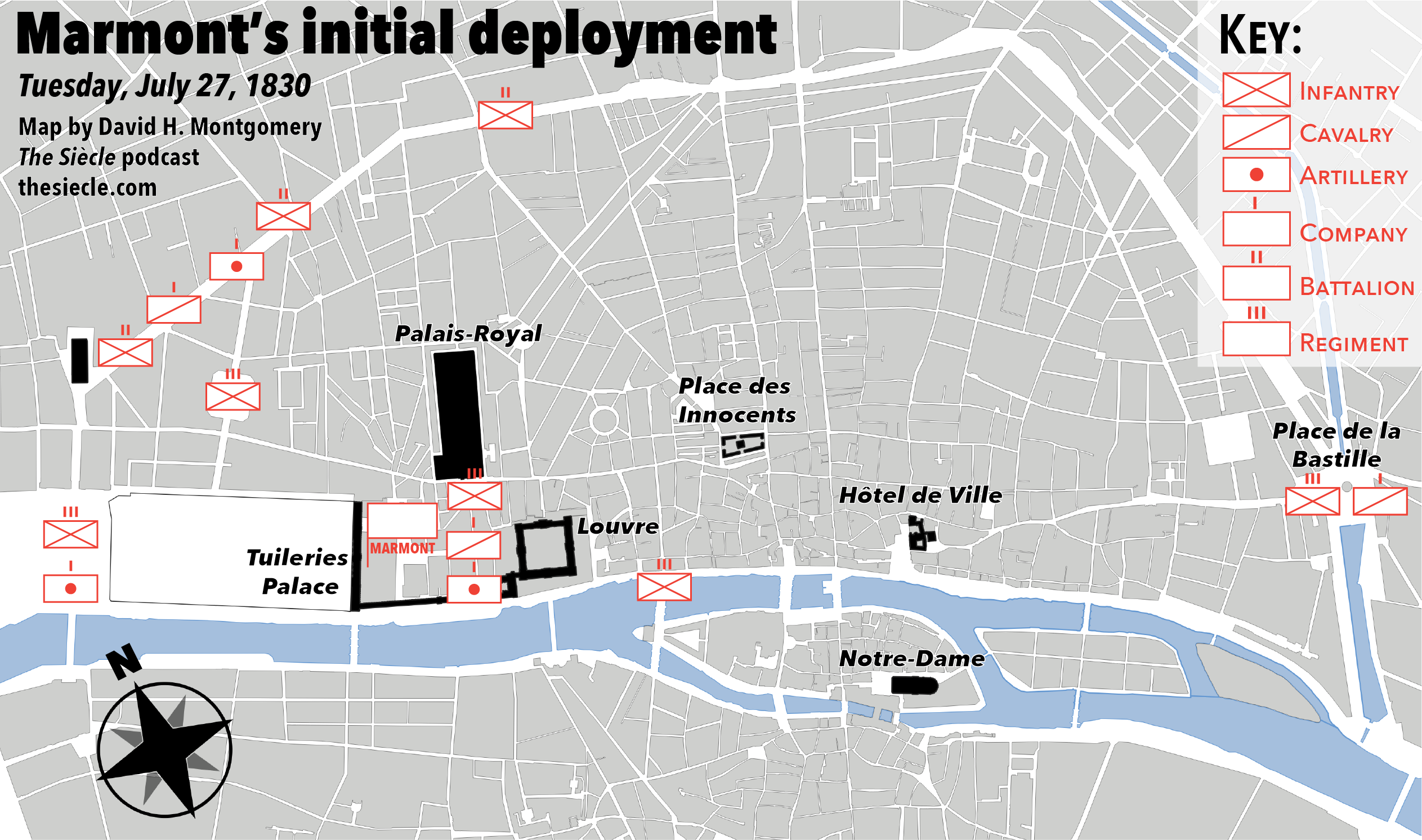

When Marmont took over on the afternoon of Tuesday, July 27, he faced a difficult situation. Gendarmes and Royal Guards had been unable to clear rioters across central Paris, and civilians were beginning to overturn carriages and pull up paving stones to build barricades. In response, Marmont deployed his new forces to occupy key strategic positions in central Paris. He had one of his seven regiments in reserve near his headquarters by the Tuileries Palace, and two more nearby on the Pont-Neuf bridge and the Place Vendôme. Most of the rest of his forces Marmont deployed to the ring of wide boulevards that encircle central Paris, in an arc from the modern-day Place de la Concorde in the west to the Place de la Bastille in the east. An artillery regiment was several miles off to the east at the fortress of Vincennes.32

Map of Marshal Marmont’s approximate initial deployment on the afternoon of Tuesday, July 27, 1830. Source: David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 103-4. Map data from Anne-Laura Bethe and Paul Rouet, Vasserot data, Analyse diachronique de l’espace urbain Parisien: approche Geomatique* (2010 and 2013).

This initial deployment serves to define our battlefield on the Right Bank of the Seine. It’s around 10 kilometers or 6.2 miles in circumference, of which 6 kilometers run along the boulevards and four along the riverbank. Inside these borders is around 4.8 square kilometers or 1.8 square miles of area. It was densely populated, full of narrow, winding streets and multi-story buildings. I can’t tell you exactly how many people lived in this area circa 1830, because the French censuses were conducted by arrondissement and the arrondissement boundaries cut across the boulevards. But just the Fourth and Seventh arrondissements, which are entirely inside these boundaries and occupy about one-fourth of its total area, had more than 100,000 residents between them. It’s safe to assume the total area that Marmont set out to guard had at least 200,000 people living in it, and probably more.33 A majority of these people didn’t take part in the fighting34 — but you don’t need a big share of 200,000 to significantly outnumber 10,000.

This initial deployment on Tuesday afternoon went off without a hitch. The soldiers encountered no resistance, and were able to dispatch patrols between their positions with messages. But there were still a whole lot of insurgents inside this perimeter, and plenty of barricades. When Marmont sent detachments to clear some of these barricades, they encountered flurries of bricks and paving stones hurled from high windows. Some barricades were cleared, but progress was slow, and some units were driven back. Officers began ordering their soldiers to return fire.35

As darkness fell, the situation got worse for the soldiers. Groups of citizens smashed all the city’s lamps, plunging the streets into deep darkness. One company of Royal Guards, sent to rescue a beleaguered Gendarmerie post, “moved in darkness” through the streets, “in silence broken only by the sound of falling glass in nearby streets.” They rescued the gendarmes, but after the soldiers had left the crowd returned, set the guard post on fire, and prevented firefighters from extinguishing it. A police agent at a different guard post penned a frantic message to the prefect at 8:30 p.m.: “We are attacked. We need help without delay.” The commander of the Paris gendarmes informed the police prefect that he had deployed almost all his reserves: “We are at the end of our resources, and you can no longer count on the forces at the disposal of the Gendarmerie of Paris.”36

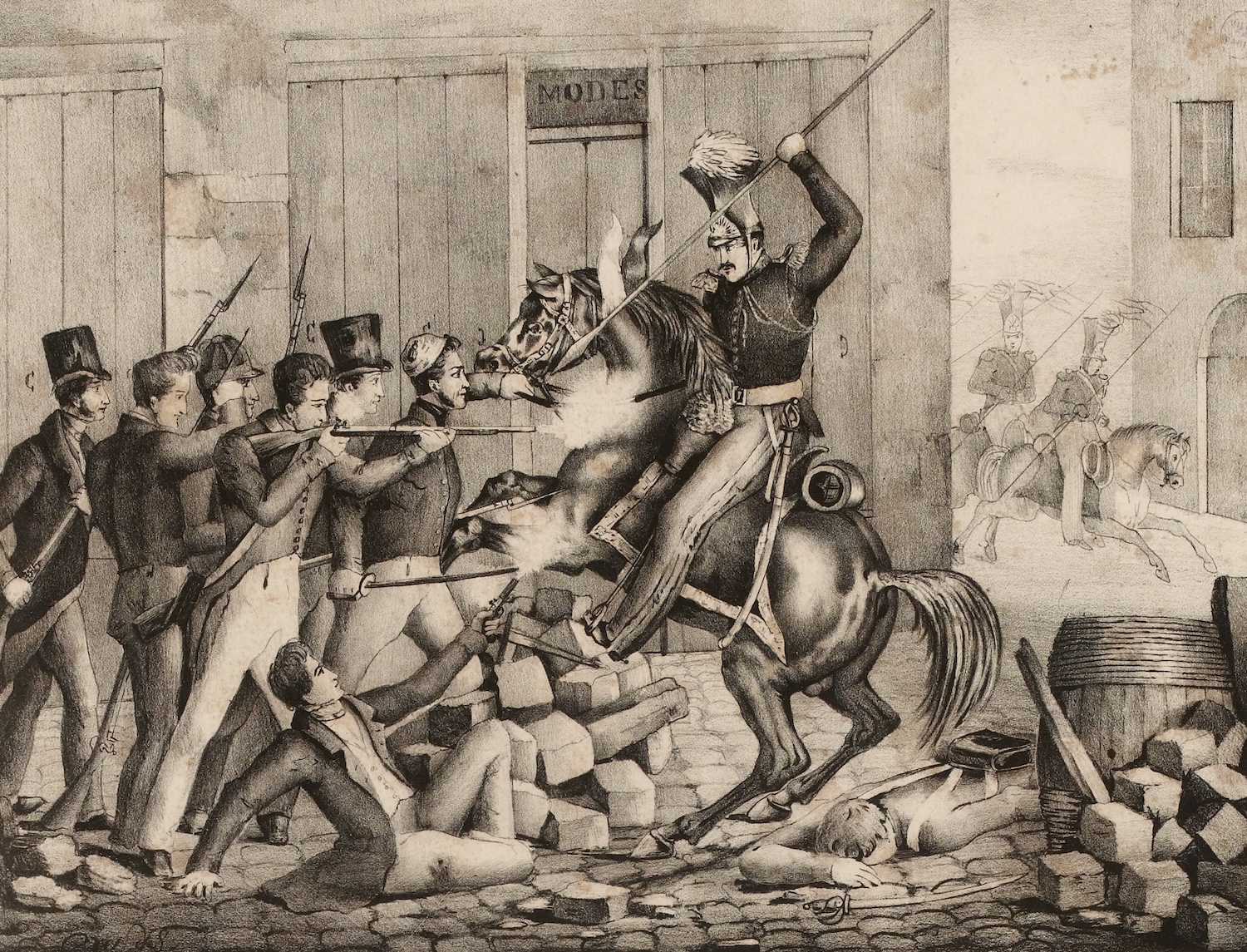

Above: A lancer breaks away from his platoon on July 28, 1830, in fighting at the Rue du Faubourg St. Antoine. Unknown artist, circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But as the evening drew on, the crowds slowly thinned. Rioters went home to sleep. Exhausted soldiers didn’t think of following them. Marmont surveyed the sudden quiet and penned a note to King Charles X, declaring victory: “the crowds had been dispersed and peace and order restored in the capital.”37

This was, of course, premature. The mood in the city on Tuesday night was not one of peace, but of ominous tension. The writer and military veteran Alfred de Vigny wrote in a story about walking the deserved boulevards after midnight, with “the pale light of [the] stars” visible amid the smashed street lamps. Here there was a mass of soldiers, resting in the darkness: “without anger, without hatred; they were resigned, and awaited whatever might happen.” Elsewhere there was a fire burning in the distance — a bonfire of elm trees, cut down by shopkeepers taking advantage of the chaos to destroy the trees that “concealed their shops.” And elsewhere, a group of workers gathered to talk, then flitted away down the “little doors of alleys, which opened like traps, and closed after them again. Nothing was stirring, and the city seemed to contain none but dead inhabitants and houses smitten with plague.”38

This was, of course, premature. The mood in the city on Tuesday night was not one of peace, but of ominous tension. The writer and military veteran Alfred de Vigny wrote in a story about walking the deserved boulevards after midnight, with “the pale light of [the] stars” visible amid the smashed street lamps. Here there was a mass of soldiers, resting in the darkness: “without anger, without hatred; they were resigned, and awaited whatever might happen.” Elsewhere there was a fire burning in the distance — a bonfire of elm trees, cut down by shopkeepers taking advantage of the chaos to destroy the trees that “concealed their shops.” And elsewhere, a group of workers gathered to talk, then flitted away down the “little doors of alleys, which opened like traps, and closed after them again. Nothing was stirring, and the city seemed to contain none but dead inhabitants and houses smitten with plague.”38

Above: Antoine Martin, lithographic portrait of Alfred de Vigny, 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Marmont’s plan

And now we finally come back to where we began this episode: the bloody day of Wednesday, July 28, 1830. Not long after dawn, crowds began to gather again, and more barricades went up. Marmont, who was on the scene at his headquarters, immediately realized his mistaken judgment the night before. He dashed off another message for the king warning that Paris was not at all pacified:

I have already had the honor of reporting to Your Majesty the dispersal of the groups that disturbed the peace of Paris. This morning they are forming again, more numerous and more threatening than before. This is no longer a riot, this is a revolution. It is urgent that Your Majesty decide on the means of pacification. The honor of his crown can still be saved; tomorrow perhaps it will be too late. For today I am taking the same measures as I did yesterday. The troops will be ready at noon, but I await with impatience the orders of Your Majesty.39

Marmont also sent messages to nearby cities, ordering their garrisons to come to Paris swiftly — an order that was only being issued now, 48 hours after the Ordinances became public. Marmont learned around this time that the night before Charles had signed an order putting Paris under martial law, with Marmont granted dictatorial powers to restore order. He was, historian David Pinkney notes, “seemingly fated to be the last to hear important news.” But crowds continued to grow, and it soon became clear something crucial had changed: beginning on Tuesday evening, insurgents had broken into the city’s gun-shops and looted large quantities of muskets. Soldiers sent to break up crowds on Wednesday morning found themselves attacked not with stones but with gunfire. More guard posts were burned, and soldiers fell back toward the Tuileries Palace. The worst defeat happened around 11 a.m., when crowds seized the Hôtel de Ville, the Paris city hall, and raised the tricolor flag from its roof. Meanwhile, the eerie silence of the night before had been replaced by the maddening sounds of the city’s church bells ringing a ceaseless alarm.40

But Marmont was far from beaten. Even as bad news filtered in, he gathered his forces and formulated a new plan. The insurgents were clearly too powerful to be dispersed by small contingents of soldiers, as he had tried the day before. Instead, Marmont would attack in force, dividing his limited army into three strong columns. He still hadn’t received new orders from the king, but decided he could no longer wait. Even more ominous than the reports that the Parisians were now armed were the reports that Parisians were fraternizing with his soldiers, sharing food and drink. With only 10,000 men, Marmont’s success depended on the Parisians giving up the fight before his soldiers did, and this fraternization did not bode well for his men’s willingness to open fire on Parisians. Marmont had “to take the offensive while he could still depend on his troops.”41

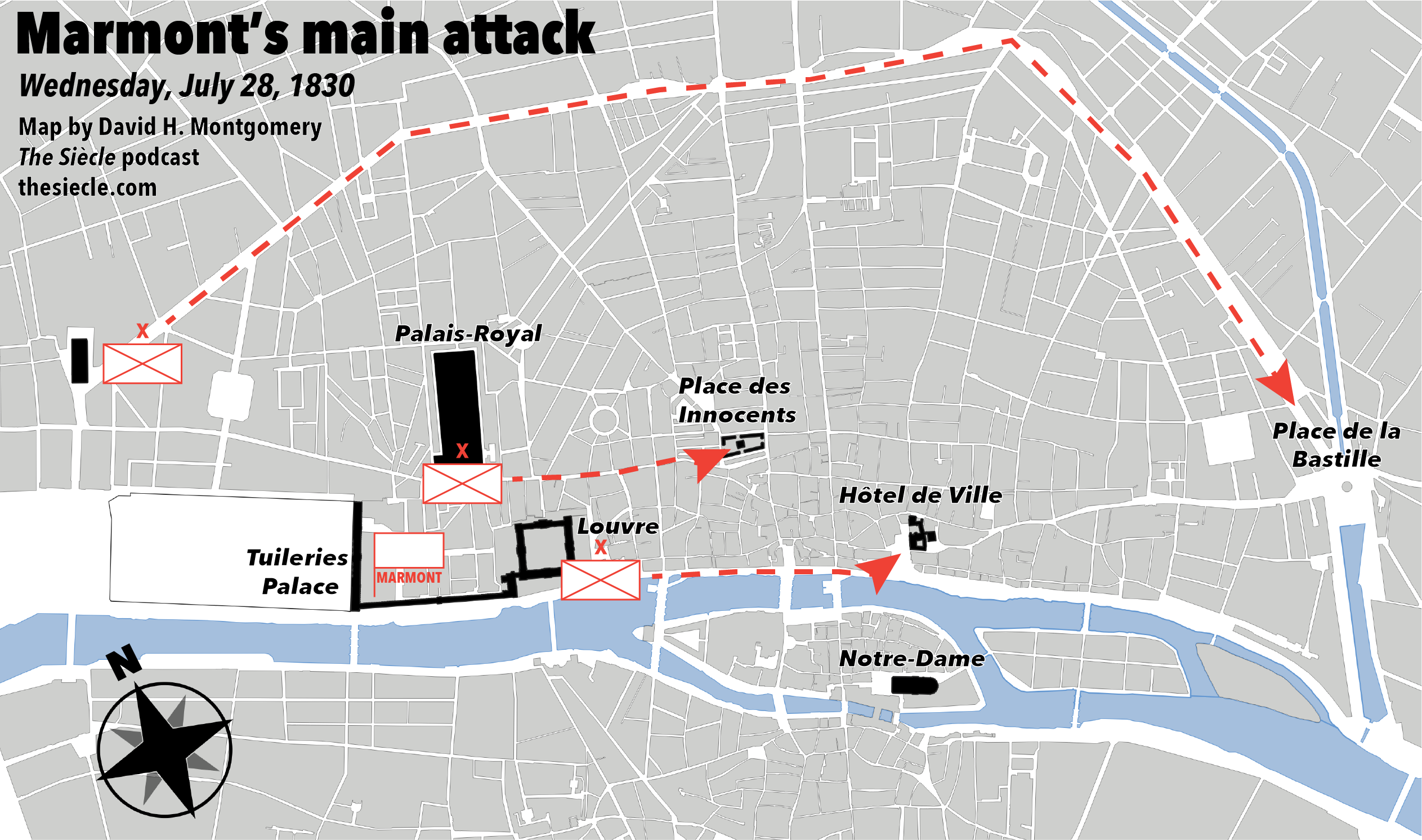

As Marmont drew up his plan, a southern column would strike east along the banks of the Seine, to retake the Hôtel de Ville from insurgents. A northern column would march along the boulevards, reaching a stranded regiment of soldiers at the Place de la Bastille. But that left the two columns separated for most of their marches by around 1.5 kilometers or 1 mile of dense city streets, so Marmoint dispatched a central column to travel in between the two and keep the north-south lines of communication open.42

Map of Marshal Marmont’s approximate plan of attack on Wednesday, July 28, 1830. Reserves, stationary detachments, and secondary movements of troops are not shown. Source: David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 113-4. Map data from Anne-Laura Bethe and Paul Rouet, Vasserot data, Analyse diachronique de l’espace urbain Parisien: approche Geomatique* (2010 and 2013).

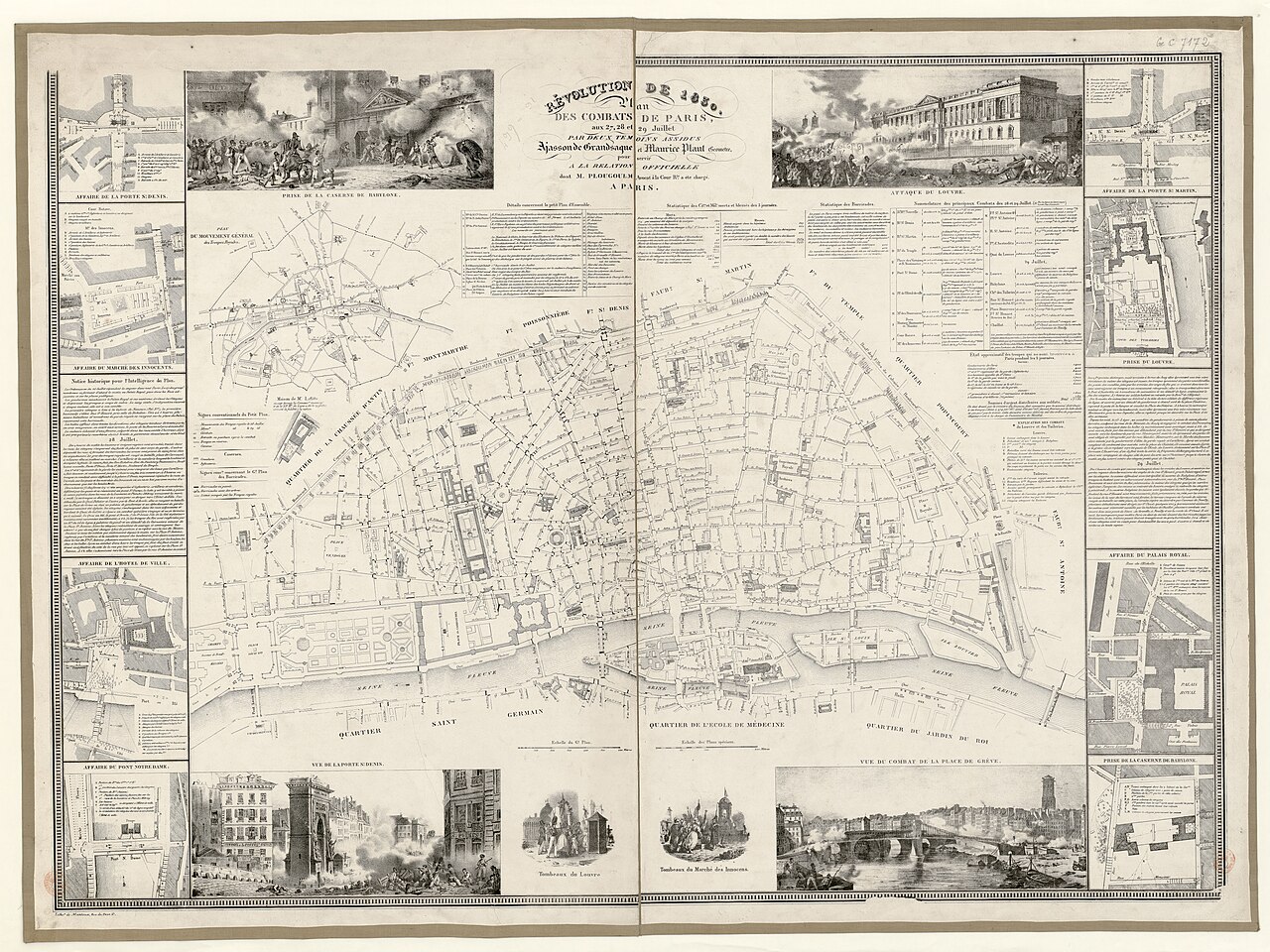

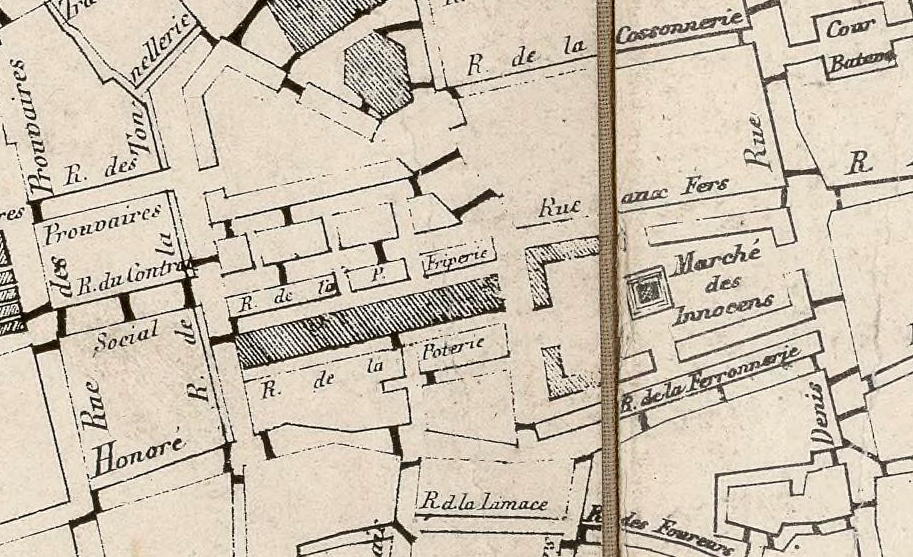

An attack in force like this might possibly have overwhelmed the Parisians on Tuesday, when the barricades were new and the insurgents armed with stones. It faced much stiffer odds on Wednesday, when the insurgents had guns, and barricades were everywhere. To give one pertinent example, the 733 meters or 800 yards that the central column had to march from the Palais-Royal to the Place des Innocents had at least 10 barricades on it, according to an astonishingly detailed contemporary map that I’ll post online at thesiecle.com/episode42. Now, most of these barricades weren’t there when the central column set off on its march Wednesday afternoon, but let me assure you that makes things worse for the soldiers. Because the barricades that weren’t there when the soldiers advanced were thrown up after they passed to cut off their retreat.43

Above: A map of the fighting on July 27 - 29, 1830, by Jean-Baptiste-François-Étienne Ajasson de Grandsagne, Maurice Plant, and Pierre-Ambroise Plougoulm, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Click the image to view a ultra-high-resolution, 32-megabyte version.

There was fierce fighting on Wednesday afternoon, which I’ll cover shortly. But for Marmont’s soldiers, logistics were a massive problem, too. It was a hot July day, and many soldiers were woefully short of food and drink. Ammunition was also in short supply, with each man allocated only 11 cartridges — severely undermining the soldiers’ firepower advantage over the civilians. And there was nothing else coming — the swarm of barricades, of insurgents melting into the buildings when soldiers appeared and re-emerging when they passed, hamstrung Marmont’s supply lines. Messages often had to be passed by aides dressed in civilian clothes to slip into the crowd. A vitally needed collection of artillery east of Paris remained out of the battle Wednesday because the streets were too dangerous to move it without a cavalry escort that Marmont couldn’t spare. The French Army had a military bakehouse in Paris that spent Tuesday night and Wednesday morning baking vast quantities of bread for the soldiers — but there was no way to get it to the men through the barricaded streets.44

The soldiers were sent out in force, and were ordered to seize their objectives and tear down barricades they encountered. But Marmont took pains to restrain the lethality of this urban warfare. His men were ordered to not open fire on massed crowds unless they were fired at by volleys of at least 50 shots — though they were allowed to shoot at civilians attacking from building windows. As Marmont had written to Charles, what was needed was some method of “pacification.” That could have meant brutal repression, but by now it was clear that Marmont didn’t have the manpower to do that. Nor, to be frank, did he have the willingness. As contemporary historian Louis Blanc wrote, “he had a very simple means in his hands of putting down the insurrection, and that was to threaten to set fire to Paris. But there are men who have neither the courage of virtue nor that of crime.”45 Marmont was strongly hinting that Charles should make political concessions — repeal the Four Ordinances, fire Polignac, something to appease the crowd and buy time to get the situation under control. But Marmont did not have the drive or imagination of his youthful friend Napoleon Bonaparte. He saw his role as strictly limited to military affairs. When opposition leaders visited him to urge peace, Marmont told them that “as a private citizen he sympathized” but that “as a military commander he had no choice but to carry out his orders to suppress the insurrection.” He obliquely suggested that the king make concessions, but did no more than suggest. Meanwhile some of Marmont’s commanders were also of the opinion that the carrot might be better than the stick — one of them wrote later that if he had been given a wagon of coins to distribute to the crowd instead of artillery, he could have calmed his district without firing a shot.46

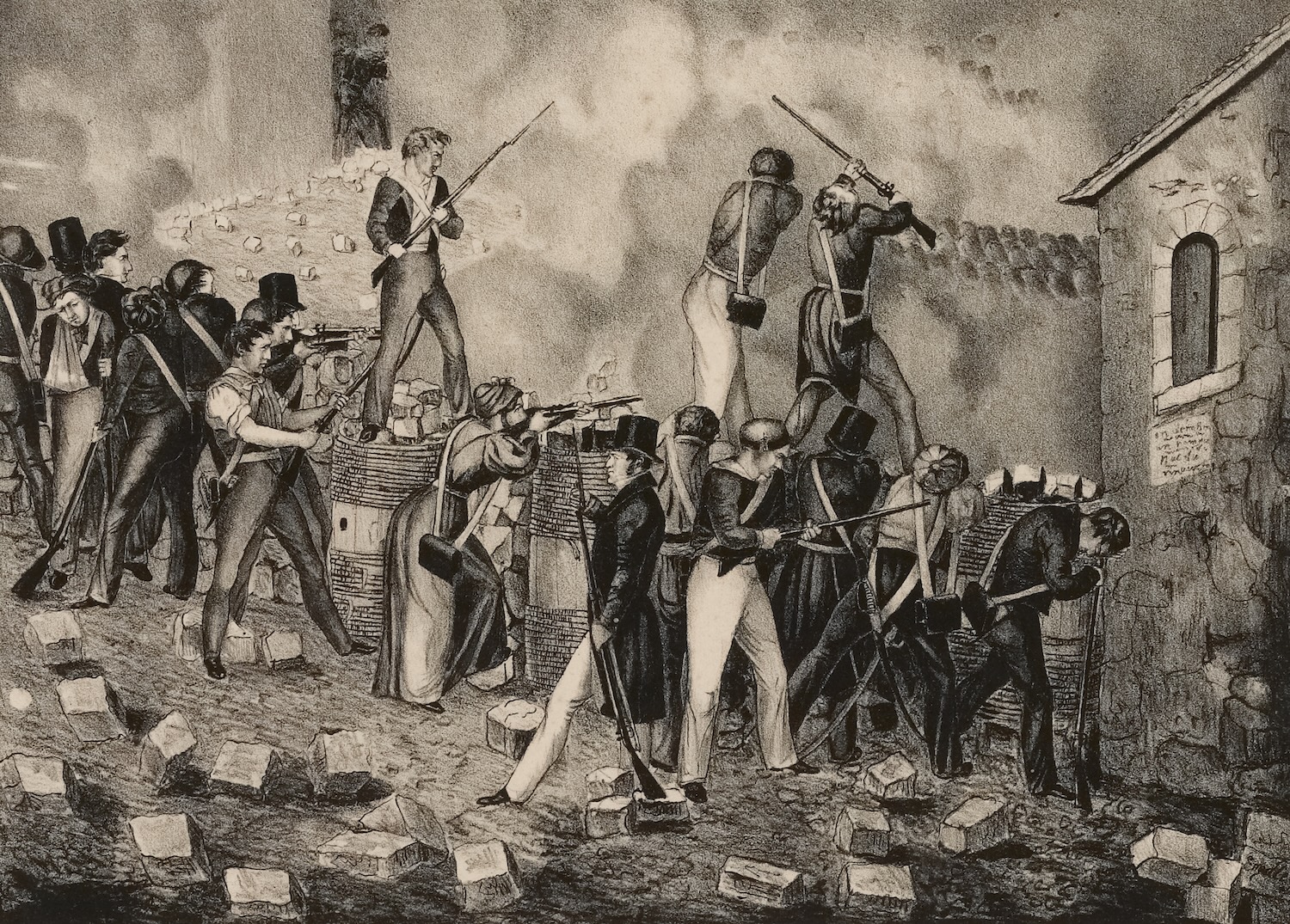

Above: Fighting at a barricade near the Hôtel de Ville. Unknown artist, circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The fighting

But there were no wagons of silver or gold coins to distribute. On Wednesday, July 28, the currency of Paris was lead and steel.

We’ll start our narrative of the afternoon’s fighting with the northern column, which had the least-bad go of it. Marching down the wide boulevards, these soldiers encountered little serious resistance except potshots from passing windows — potshots to which the soldiers, as authorized by Marmont, returned fire. They reached the Place de la Bastille with modest casualties — though several battalions had exhausted their limited ammunition firing at snipers. Once there, they found the local populace fairly quiet, and prepared to return back to Marmont at the Tuileries Palace, only to discover that barricades had sprung up on the boulevards behind them, impeding their retreat.47

Below: Detail from a map of the fighting on July 27 - 29, 1830, by Jean-Baptiste-François-Étienne Ajasson de Grandsagne, Maurice Plant, and Pierre-Ambroise Plougoulm, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Click the image to view a higher-resolution version.

The central column likewise found little resistance on its initial advance to the Place des Innocents, as I noted. But as the column took up positions in the square, insurgents emerged out of the woodwork to barricade the square’s entrances. Four companies of infantry, two cannons and 15 mounted gendarmes were trapped — and worse, exposed. What one officer called “a disgusting populace” opened fire from windows and barricades on the soldiers in the center of the square. There was little cover except for some market stalls. After hours of fighting, the soldiers were still trapped, still hungry and thirsty, but now beginning to run low on ammunition. An aide disguised in civilian clothes snuck through to Marmont with a report, and the marshal promptly dispatched two companies from his reserve to the rescue. But the rescuers soon found themselves in a pickle, trapped between two barricades. Some soldiers deserted, going over to the side of the rebels, and the colonel in charge of the rescue force gave up and led a fighting retreat. Another rescue force, a battalion of Swiss Guards, had a more embarrassing experience: they got lost in the winding Paris streets and wandered around under fire for crucial hours. Eventually, the Swiss finally reached the Place des Innocents — but they, too, were now low on ammunition. Still, the combined force held together and forced its way out of the square and south to the banks of the Seine.48

The central column likewise found little resistance on its initial advance to the Place des Innocents, as I noted. But as the column took up positions in the square, insurgents emerged out of the woodwork to barricade the square’s entrances. Four companies of infantry, two cannons and 15 mounted gendarmes were trapped — and worse, exposed. What one officer called “a disgusting populace” opened fire from windows and barricades on the soldiers in the center of the square. There was little cover except for some market stalls. After hours of fighting, the soldiers were still trapped, still hungry and thirsty, but now beginning to run low on ammunition. An aide disguised in civilian clothes snuck through to Marmont with a report, and the marshal promptly dispatched two companies from his reserve to the rescue. But the rescuers soon found themselves in a pickle, trapped between two barricades. Some soldiers deserted, going over to the side of the rebels, and the colonel in charge of the rescue force gave up and led a fighting retreat. Another rescue force, a battalion of Swiss Guards, had a more embarrassing experience: they got lost in the winding Paris streets and wandered around under fire for crucial hours. Eventually, the Swiss finally reached the Place des Innocents — but they, too, were now low on ammunition. Still, the combined force held together and forced its way out of the square and south to the banks of the Seine.48

Above: Leon Auguste Asselineau, fighting at the Place des Innocents on July 28, 1830, unknown date. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

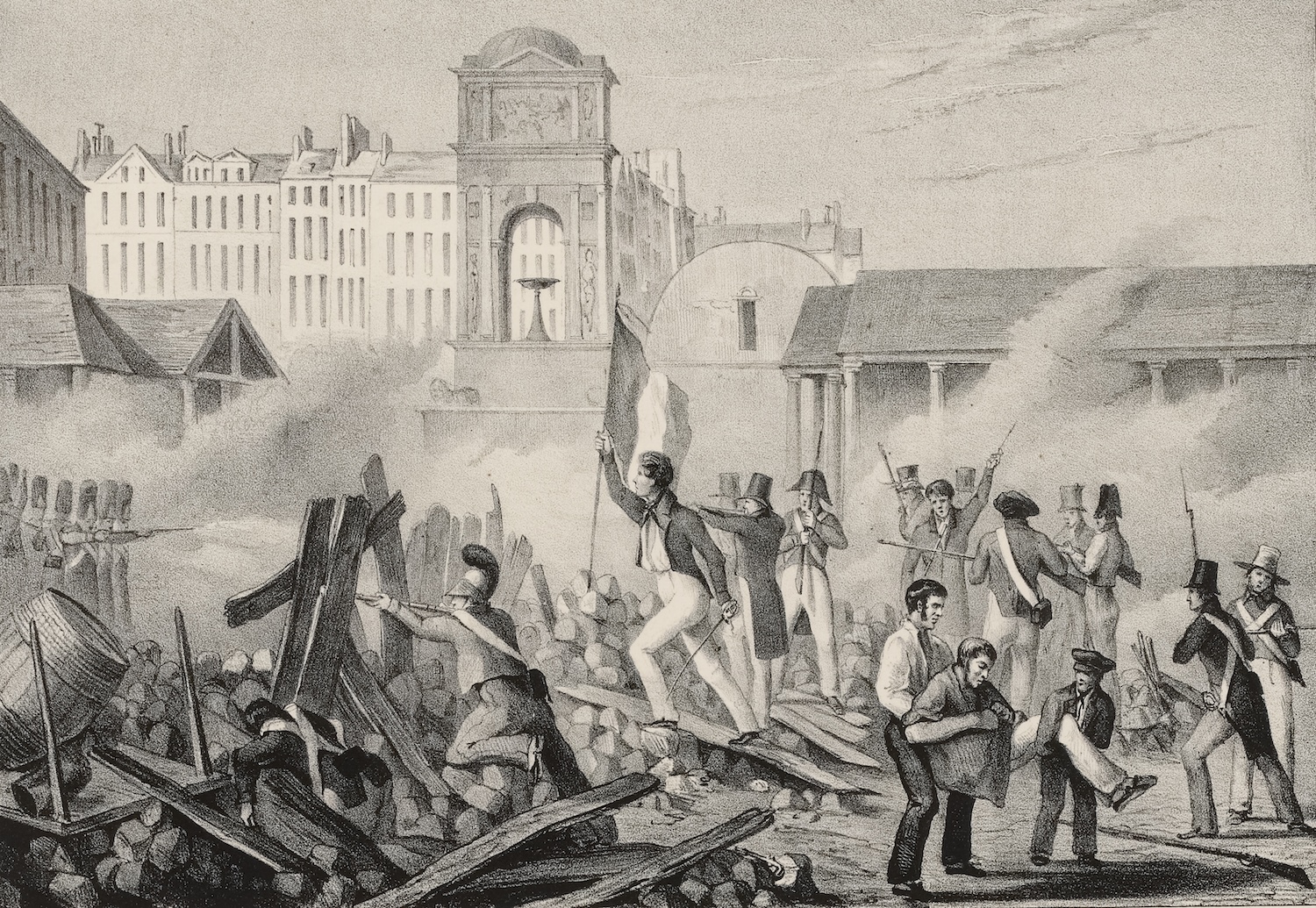

The southern column encountered the fiercest fighting. Marching along the riverbank, they were attacked by mass volleys from barricades on side streets — and returned fire with cannons that sent the rebels scattering. They reached the Hôtel de Ville and came under fire from insurgents in the windows. Swiss Guards forced their way into the city hall and cleared it out in hard hand-to-hand fighting, but after that, their advance culminated. No new supplies came, and eventually the commander moved his entire force inside the relative safety of the Hôtel de Ville.49

There were other forces nearby that might have helped. The northern column cooling its heels at the Place de la Bastille ultimately tried to push west to assist the soldiers at the Hôtel de Ville, but encountered a particularly robust barricade. The insurgents used clever tactics, such as allowing the royal vanguard to break through, then unleashing gunshots and paving stones from above as they picked their way over the barricade. The northern column made no progress. Ultimately, in the early evening, a new order from Marmont got through: they were to retreat. A final attempt to reach the Hôtel de Ville failed, and the detachment ultimately slunk home across the river, in the less-contested Left Bank. Meanwhile the central column had retreated down to the banks of the Seine, but their fighting spirit was drained. When the southern column finally abandoned the Hôtel de Ville and retreated late at night, they passed the central column, exhaustedly bivouacked on the riverbank.50

Above: “Attack on the Hôtel de Ville (July 28, 1830),” unknown artist, circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

All three columns ultimately made their way back to Marmont’s headquarters late Wednesday night, bloodied, exhausted, and utterly unsuccessful in achieving their objectives. The soldiers had fought hard despite severe supply limits and a punishing urban battlefield, but they had no more fight left in them. Marmont told Polignac — who had been urging him to hold firm — that he could not resume the attack on Thursday. The best he could hope for, Marmont reported, was to hold a defensive position around the Tuileries Palace and the Louvre. He thought he could hold this position for three days — long enough for the belated reinforcements to arrive from the provinces.51

An assessment

We’ll see in a future episode how this hope turns out for Marshal Marmont. But I wanted to pause now to take a step back from the streets of Paris and make sense of all this.

Marmont was undeniably put into a terrible military situation — thrust into command with no warning, with starkly inadequate forces for the mission at hand. Even Napoleon himself might have struggled to win a similar battle.

But even given that, observers at the time and ever since have not rated Marmont’s performance as a general on July 27 and 28 very highly. Marmont failed to secure his supply lines, or to prevent the seizure of vital armaments by the insurgents. He repeatedly divided his already outnumbered force — into small squadrons on Tuesday, and into the attack columns on Wednesday — that weren’t able to support each other and were never sufficient for the task at hand.52

Earlier, I mentioned how Marmont knew he couldn’t kill all the civilians — he had to persuade them to stop fighting. It was a battle of morale. For the Parisians, like those seen fraternizing with Marmont’s troops Wednesday morning, that meant persuading the soldiers to mutiny or desert, to refuse to fire on their fellow countrymen. Many civilians cleverly tried to drive a wedge between the different components of Marmont’s army: the regular “troops of the line” on the one hand, and the Royal Guard and gendarmes on the other. Civilians coming into contact with Marmont’s forces were frequently observed to chant, “Long live the Line, down the with the Guard!”53

For Marmont, winning the battle of morale meant showing the insurgents the costs of their insurgency by bringing them face to face with his professional battalions, lancers, and artillery. And this wasn’t necessarily an absurd strategy. A reckless charge into a determined opponent can get your troops massacred; that same charge into a wavering opponent might send them running and win the day. Marmont’s strategy of sending in the army as a show of force might have worked if the Parisians had been less determined — if they had been mere rioters, out on the streets to smash some windows and throw some rocks, but not prepared for an actual fight. Unfortunately for Marmont, the Parisian insurgents in July 1830 were considerably more determined than that. They didn’t flee home when faced with soldiers. And so when civilians went toe to toe with Marmont’s columns from barricades and apartment windows, they had essentially already won the only battle that really mattered: the battle of morale.

Marmont did adapt his strategy as it became clear his earlier approaches weren’t working — but often too little, too late. His command was characterized by a general lack of initiative, including frequently waiting idly for crucial hours for orders to come from King Charles.54

Alfred De Vigny, in the work I quoted from earlier, wrote how the French military of the age was marked by a spirit he called “passive obedience.” “The most absurd, the most stupid order must be obeyed without a word,” de Vigny wrote. He acknowledged that in an army, obedience is necessary: despite the problems of passive obedience, he says “things would be much worse if it did not exist.” But de Vigny also gives examples of generals in the Napoleonic wars putting themselves in absurd situations by practicing passive obedience instead of exercising initiative. “They were afraid of only one thing,” de Vigny notes: “not obeying punctually the orders which they had received.”55

It’s not hard to see something of this spirit in Marmont, waiting haplessly for orders to come from King Charles, miles and miles away from the action. Nor is it difficult to understand why an experienced officer like Marmont, who had demonstrated independent command in the past, might prefer a spirit of passive obedience when enforcing laws he personally opposed. This spirit of passive obedience didn’t help Marmont win the battle — but it may have eased his soul.

The sheep

There is one final indignity we need to pile on poor Marshal Marmont today — a crowning absurdity that takes his story from tragic to tragicomic. Because had things gone differently, Marmont wouldn’t have been around to be given this cursed command. He should have been safely retired. Which means it’s time, finally, to bring in the sheep.

By now you’ve already gotten a certain image of Auguste de Marmont’s personality. He was a professional soldier and an able administrator. His record of judgment on the battlefield was mixed, but he had undeniable physical courage and a gift for the intellectual side of warfare. In the Restoration, he toured Europe to study the organization of other European armies; later in life, he published a well-regarded work of military theory.56 This was a man was a member of the French Academy who hung around with astronomers. So it should come as no surprise that when Marmont found himself wealthy and idle during the largely peaceful Bourbon Restoration, he didn’t just retire to his country estates — he tried to improve his estates.

Above: Fighting at the Hôtel de Ville, July 28, 1830. Unknown artist, circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This itself was not unusual for wealthy and prominent men like the Duke of Ragusa. Rural France at this time was dotted with agricultural societies, devoted to sharing the latest insights and conducting experiments into new agricultural methods, and nobles — even peers of the realm, like Marmont — were prominent members.57 Being this kind of innovative landowner matched Marmont’s ambitions precisely — especially because he was rich, but not that rich. Marmont wanted to experiment, but he also needed his experiments to pay off. If they did so, it might make him fabulously wealthy. And wealth brought with it respect — respect that Marshal Marmont found in short supply after his controversial 1814 surrender.58

Working from a small estate in eastern France, Marmont explored different forms of industry and agriculture before settling on sheep as his best bet. Sheep could produce meat, fertilizer, and especially wool, increasingly sought after by France’s burgeoning textile industry. He began buying purebred merino sheep in 1816. In the first few years he spent more than 10,000 francs buying 142 merino sheep — a price “considered very high at the time” — as well as hundreds of other sheep of less prestigious breeding. Some of this outlay was soon lost when some of the newly purchased sheep began to die. It seems area shepherds had taken advantage of this free-spending general to offload weaker animals from their flocks.59

Undeterred, the forward-thinking Marmont hired a veterinarian to help run his operation and vet his purchases. Through births and continued purchases, Marmont soon owned nearly 5,000 sheep, who were beset by all kinds of disease: sheep pox, scabies, anthrax, and a tapeworm infection called “turning disease.” Marmont fought back, including by vaccinating his flocks against sheep pox, just a few decades after Edward Jenner’s pioneering work. The vaccination campaign was successful.60

Unfortunately, another effort to protect Marmont’s sheep proved to be a fiasco.

The idea, as the story was related by Marmont’s friend, the Comtesse de Boigne, was that Marmont would protect his sheep from infections by giving the sheep clothes — overcoats, morbidly sewn from the skin of other sheep, on top of their natural wool. As Marmont drew up his business plan, each sheep-jacket would cost four francs, and would last 18 months. The protected sheep would produce finer wool that could be sold for six or seven francs extra, and deaths from disease would be sharply reduced. The countess reports that Marmont spent all winter bragging about his “dressed sheep.”61

The idea, as the story was related by Marmont’s friend, the Comtesse de Boigne, was that Marmont would protect his sheep from infections by giving the sheep clothes — overcoats, morbidly sewn from the skin of other sheep, on top of their natural wool. As Marmont drew up his business plan, each sheep-jacket would cost four francs, and would last 18 months. The protected sheep would produce finer wool that could be sold for six or seven francs extra, and deaths from disease would be sharply reduced. The countess reports that Marmont spent all winter bragging about his “dressed sheep.”61

Right: Jean-Baptiste Isabey, portrait of Adélaïde d’Osmond, Comtesse de Boigne, 1810. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Unfortunately for Marmont, this scheme turned out to be a bit woolheaded. The Comtesse de Boigne claims the sheep-jackets cost seven francs each — nine francs after accounting for the cost of regular repairs. That’s a 125 percent cost overrun. Meanwhile the jackets only lasted 12 months, not 18. The wool did sell for more — but only a two-franc premium. And diseases were “at least as frequent” as before. That’s not even counting the opinion of the poor sheep, who the countess describes as looking “almost stifled by the heat” in their extra layers.62

If we take the countess’s numbers at face value, then every sheep-jacket cost nine francs extra to generate two extra francs in revenue, a seven-franc loss per sheep. With nearly 5,000 sheep, we’re talking net losses in the tens of thousands of francs. Expecting windfall profits, Marmont had paid for the sheep and their accoutrements by borrowing heavily. When those profits didn’t materialize, Marmont was in deep trouble — and then things got far worse when France was hit by the Panic of 1825, a widespread recession that I discussed in Episode 35.63

This sheep-jacket debacle is very funny. But it also ended up mattering. The only way Marmont could make the payments on his massive debts was to garnish his military salary. Almost all his income was pledged to his creditors.64

Now we come forward to 1830 — but not yet to July. As Jules de Polignac planned out France’s invasion of Algiers, it was an open question as to who would be put in charge of the operation. Marmont desperately wanted this honor, but as we’ve seen, the command went to the war minister, Bourmont. Insulted at being passed over, Marmont considered resigning in protest. But he couldn’t quit — he needed his salary to pay the massive debts he had incurred from his disastrous sheep-jacket venture. So Marmont gritted his teeth and kept his job. Which meant that when Jules de Polignac needed to appoint a general to command the Paris garrison, just in case there was any unrest, it was Auguste de Marmont’s turn in the rotation.65

As he sent columns of hungry, under-equipped soldiers marching against Parisian barricades, in defense of a government he despised and ordinances he opposed, Marshal Marmont might have wished he had escaped to Italy, as he had first hoped. He even might have wished he was back on his ruined farm in eastern France. But he wasn’t. Thanks to his sheep, Marmont was here in Paris, and he would do his duty — even if it ruined him.

Thank you all for following along. This has been one of my favorite episodes of the show so far. Marmont is such a tragicomic figure — talented, but doomed by his own flaws to undermine everything he holds dear. We’re not done with him yet, though. Instead, we’re going to follow another group of men who met with Marmont on Wednesday afternoon. Because if Marmont’s columns couldn’t end the rebellion, and Charles wouldn’t end the rebellion, then that left the initiative in the hands of everyone’s favorite class of people. Join me next time for Episode 43: The Politicians.

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 76. ↩

-

Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 291-2. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 43. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 76-7, 90. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 90. Comtesse de Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne: 1820-1830, Vol. 3, ed. Charles Nicoullaud (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 260. Note that the quotes from Marmont come from a memoir written years later; all such sources should be viewed with some skepticism, but something like these sentiments is entirely in-character for Marmont. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 100-1. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 101. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 103. ↩

-

John L. Pimlott, “‘Friendship’s Choice’ — Marmont,” in Napoleon’s Marshals, ed. David G. Chandler (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), 256. Andrew Roberts, Napoleon: A Life (New York: Viking Penguin, 2014), 45. ↩

-

Pimlott, “Marmont,” 257. ↩

-

Pimlott, “Marmont,” 259. ↩

-

Pimlott, “Marmont,” 260. ↩

-

Pimlott, “Marmont,” 265-7. ↩

-

Review of “Mémoires du Duc de Raguse, de 1792 à 1832,” by Auguste de Marmont, Duc de Raguse, The Edinburgh Review 215 (July - October, 1857), 81. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 6-7. ↩

-

Roberts, Napoleon, 708-9. Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 8-9. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 75-6. ↩

-

Procès des ministres de Charles X […] (Paris: Lequien, 1830) (statement of Dominique-François Jean Arago), 178-9. ↩

-

Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 260. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 103-4. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 102. Note that some sources give somewhat higher numbers for the forces at Marmont’s disposal; I am following Pinkney’s analysis. ↩

-

Munro Price, The Road from Versailles: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and the Fall of the French Monarchy (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 76. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 236. ↩

-

Daniel L. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827-30 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 224. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 236-7. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 103. ↩

-

“Paris Arrondissements: Population & Density: Pre-1860 Definitions,” Demographia, accessed September 5, 2024. ↩

-

Records of civilians killed in the fighting as combattants (as opposed to as bystanders) report that the dead are all male and almost all adults. This instantly excludes a majority of the population from serious fighting, though this is not to say there weren’t combattants who are not demographically represented on the fatality list. The combattants are also disproportionately skilled workers of moderate means, excluding significant portions of the top and bottom of the income distribution. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 254-7. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 103-5. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 105-7. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 107. ↩

-

Alfred de Vigny, Servitude et grandeur militaires [Recollections of Military Servitude], vol. 1, in Lights and Shades of Military Life, edited by Charles James Napier, translated by Frederic Shoberl (London: H. Colburn, 1840), 181-3. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 109-10. Marmont actually sent two messages that morning, but the first message was mysteriously mislaid by its messenger and is lost to history. His second message, sent at 9 a.m., survives and is quoted here. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 242, Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 105, 110-3. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 113. ↩

-

Louis Blanc, The History of Ten Years: 1830-1840, vol. 1, translator unknown (London: Chapman and Hall, 1844), 110. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 113-4. ↩

-

Jean-Baptiste-François-Étienne Ajasson de Grandsagne, Maurice Plant, and Pierre-Ambroise Plougoulm, “Révolution de 1830. Plan des combats de Paris, aux 27, 28 et 29 Juillet […].” Wikimedia Commons. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 114-5. Pinkney relates that on their advance, the central column encountered only a single unmanned barricade and some scattered potshots, but that soon after they entered the square, crowds threw up barricades to block the entrances. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 242-3. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 110, 114-6, 122. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 114. Blanc, The History of Ten Years: 1830-1840, 110. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 125. Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 244. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 119. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 114-6. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 117-8. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 118-21. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 129. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 242. [Hippolyte Poncet de Bermond], Military events of the late French revolution, or, An account of the conduct of the Royal Guard on that occasion / by a Staff Officer of the guards, translator unknown (London: John Murray, 1830), 23. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 105. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X, 372-3. Even after messengers crossed the miles between the Tuileries and St. Cloud, where Charles was, they were often still forced to wait crucial minutes or even hours for reasons of “court etiquette.” ↩

-

Alfred de Vigny, Servitude et grandeur militaires, vol 1, 28, 88-9. Alfred de Vigny, Servitude et grandeur militaires, vol. 2, 247, 252-3 et al. Richard Holroyd, “The Bourbon Army, 1815-1830,” The Historical Journal, Vol. 14, No. 3 (September 1971), 543 ↩

-

Holroyd, “The Bourbon Army, 1815-1830,” 544. Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont (duc de Raguse), The Spirit of Military Institutions: Or, Essential Principles of the Art of War, tr. Henry Coppée (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862). ↩

-

David Higgs, Nobles in Nineteenth-Century France (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 52-3. ↩

-

Célestin Courtois, “Marmont et l’économie rurale de la région chatillonnaise: L’élevage du mouton,” Annales de Bourgogne, vol. 8 (1936), 236. Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 158-9. My thanks to Munro Price for help in locating the passages of the Comtesse de Boigne’s memoirs discussing Marmont’s sheep. ↩

-

Courtois, “Marmont et l’économie rurale,” 234-5, 240-1. ↩

-

Courtois, “Marmont et l’économie rurale,” 242, 246-7, 249-50. ↩

-

Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 159. ↩

-

Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 159-60. ↩

-

Courtois, “Marmont et l’économie rurale,” 237. ↩

-

Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 159-60. ↩

-

Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 143-4. ↩