Episode 44: Bourbons on the Rocks

The candles flickered in the dark as King Charles X of France and his courtiers shuffled their playing cards in the Palace of Saint-Cloud. The king was playing his favorite game, whist, as he did almost every night. He and his three fellow players were “tranquil” and “absorbed in their game” — which was a little unusual, since Charles was known for being a sore loser who frequently lost his temper while playing. Tonight he was calm.1

But what made this game more unusual was its backdrop. Because as the blue-blooded players vied to take tricks, out on the balcony the horizon was bright with fire, while the murmurs of the whist players were punctuated by the distant sound of bells and gunfire. It was Wednesday, July 28, 1830, and while King Charles played his nightly game of cards, men were fighting and dying a few miles away in Paris. It was the second day of street fighting after Charles had issued the Four Ordinances, a royal coup d’état that dissolved the French parliament, rewrote the election laws, and censored the press. But that was no reason to interrupt the rituals and routines of France’s royal court. So the cards came out, as they did almost every night. Courtiers watched in silence, saying nothing of the violent catastrophe visible from the window.2

My sources do not record how many times the king won and lost his game of cards this Wednesday evening. And why would they? The stakes were low: little more than royal pride. But whether he admitted it or not, that evening Charles was in the middle of a game where his very throne was at stake, and where royal pride was one of the key players.

This is The Siècle, Episode 44: Bourbons on the Rocks.

Welcome back, everyone! Last time, we covered how France’s politicians responded to the Four Ordinances in July 1830 — haltingly at first, but consensus beginning to grow for stronger stances as the fighting progressed. Today, we’re following King Charles and other members of the House of Bourbon as these great princes grapple with the unfolding chaos. It’s a great episode — and also, to my own amusement if nothing else, the payoff to a joke I set up five years ago in Episode 13: Bourbons, Neat.

First, I wanted to as always thank The Siècle’s podcast network, Evergreen Podcasts, and all the supporters on Patreon that make this show possible. Sixteen of you have made new pledges of as little as $1 per month since last episode, supporting the show and receiving an ad-free feed. Thank you to Steffen Gracchus, Ned Raggett, A.M., Karl Buch, Marc Dalesslo, Derek Kirkland, Ren Stover, Nicholas Lundgaard, Lex Hall, Pippa Johnson, Spencer Cotkin, David Sulitzer, Richard Jost, Stlan Reklev, AnimatedRNG, and Nami Liu.

You can find out how to join them, or see an annotated transcript of this episode, online at thesiecle.com.

Now, let’s see what our friend King Charles has been up to!

The hunt

On Sunday, July 25, 1830, Charles had met with his ministers six miles west of central Paris at the royal palace of Saint-Cloud. (It’s spelled like “Saint Cloud.”) There, as I covered in Episode 39, the king had signed the Four Ordinances. They were published the next morning in the Moniteur newspaper, provoking first shock, then protests, then riots, and finally revolution. But at first, Charles did not let these matters interfere with his normal daily life.

On Monday, July 26, for example, while Paris was dealing with the bombshell of the Four Ordinances, Charles went on a hunting trip. That morning, the king and his son, the Duc d’Angoulême, got into a carriage to go hunting at the forest of Rambouillet, some 44 kilometers or 27 miles southwest of central Paris.3

There was nothing particularly unusual about this hunting trip. Along with nightly games of whist, hunting was one of Charles’s favorite forms of recreation. A typical hunting trip might involve lining up as many as 150 Royal Guardsmen to beat the bush and flush out game. Charles was always in the middle of the line, gun in hand; his son Angoulême was at the king’s right hand, while the spot to the king’s left was given as a favor to some friend or courtier. The three of them — and only those three — were allowed to fire at the animals flushed loose by the hunting party. Charles, we are told, was a pretty good shot. The poet Alphonse de Lamartine wrote that Charles’s “hunting trains… were more than an amusement — they were a royal occupation for him.”4

There was nothing particularly unusual about this hunting trip. Along with nightly games of whist, hunting was one of Charles’s favorite forms of recreation. A typical hunting trip might involve lining up as many as 150 Royal Guardsmen to beat the bush and flush out game. Charles was always in the middle of the line, gun in hand; his son Angoulême was at the king’s right hand, while the spot to the king’s left was given as a favor to some friend or courtier. The three of them — and only those three — were allowed to fire at the animals flushed loose by the hunting party. Charles, we are told, was a pretty good shot. The poet Alphonse de Lamartine wrote that Charles’s “hunting trains… were more than an amusement — they were a royal occupation for him.”4

Above: Goberté, “Le Tirant [The Tyrant],” caricature of Charles X hunting, 1830. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The opposition press loved to attack Charles for spending so much time hunting, in a manner not dissimilar to how modern U.S. presidents are sometimes attacked for golfing too much. Charles was nicknamed “Robin Hood,” and newspapers made sure to publicize each expedition. His friend the Duc de Doudeauville defended the hunting trips as necessary breaks from the busy work of governing the country: “Twice a week, and often only once, weather permitting, he leaves his dreary prison and goes hunting,” Doudeauville wrote.5

This particular hunting trip began under the shadow of the Four Ordinances. Before Charles left, he had met his 10-year-old granddaughter Louise and his nine-year-old grandson, Henry. Their governess, the Duchesse de Gontaut, was horrified when Charles told her about the Four Ordinances, but the king replied that she had “a very good heart” but “let it overpower your good sense.” There was nothing to worry about, he said:

This particular hunting trip began under the shadow of the Four Ordinances. Before Charles left, he had met his 10-year-old granddaughter Louise and his nine-year-old grandson, Henry. Their governess, the Duchesse de Gontaut, was horrified when Charles told her about the Four Ordinances, but the king replied that she had “a very good heart” but “let it overpower your good sense.” There was nothing to worry about, he said:

Calm yourself, and enjoy your day. I shall spend it at Rambouillet, so you can see that my mind is perfectly easy with regard to the result of the measures of which I have spoken to you.6

While the governess of the young royals was worried about the Four Ordinances, their mother was overjoyed. Marie-Caroline, the Duchesse de Berry, was an Italian princess who had married Charles’s son, the Duc de Berry. The duke had been assassinated in 1820, but it turned out Marie-Caroline had been pregnant. Months later, she gave birth to Henry — a long-awaited male heir to continue the Bourbon line. (I covered all that in Episode 15: The Miracle Child.) The Duchesse de Berry ran up to Charles as he was preparing to leave, holding that morning’s Moniteur. “At last you are truly king!” she exclaimed. “My son will owe his crown to you, and his mother thanks you!”7

Above: Adolphe Ladurner, “The Duchesse de Gontaut, governess of the Children of France, walks Louise d’Artois and her brother, Henri, Duc de Bordeaux, in the gardens of Saint-Cloud,” 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

With that farewell, Charles and his son left for their hunt. They would not return to Saint-Cloud until around 11 p.m. Despite the late hour, protocol dictated that the royal court welcomed the king back on the chateau steps, so assorted aristocrats were there waiting — bubbling with news from Paris. One of them, Marshal Auguste de Marmont, Duc de Raguse, told Charles and Angoulême that there had been “great consternation” and “great dejection” in Paris. Besides street disorder, Marmont said, there had been “an extraordinary drop” in the value of government bonds at the Bourse, the official stock market. Angoulême waved it off. “They will go back up,” the prince said. The two royals retired to bed. Charles did not think to inform Marshal Marmont in this conversation that he had been appointed commander of the Paris garrison.8

Orleans

Below: Louis Hersent after François Gérard, “Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, with his sons the dukes of Chartres and Nemours, 1830,” circa 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A few miles away at another castle, another French prince had had a somewhat different response to the news on July 26. It was the Chateau de Neuilly, which today is part of a wealthy Parisian suburb, but which at the time was a 420-acre estate owned by Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans and the cousin to the king. Louis-Philippe had been third-in-line for the French throne until the birth of the Duc de Berry’s “Miracle Child” in 1820. By now, the Duc d’Orléans had resigned himself to never inheriting the throne. He supported his cousin King Charles, despite the fact that the two men had very different politics — Charles was well-known to be an Ultraroyalist, while Louis-Philippe was close to the liberal opposition. But Charles was always unfailingly polite and respectful to Louis-Philippe despite their differences of opinion, and Louis-Philippe had returned the friendliness.9

A few miles away at another castle, another French prince had had a somewhat different response to the news on July 26. It was the Chateau de Neuilly, which today is part of a wealthy Parisian suburb, but which at the time was a 420-acre estate owned by Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans and the cousin to the king. Louis-Philippe had been third-in-line for the French throne until the birth of the Duc de Berry’s “Miracle Child” in 1820. By now, the Duc d’Orléans had resigned himself to never inheriting the throne. He supported his cousin King Charles, despite the fact that the two men had very different politics — Charles was well-known to be an Ultraroyalist, while Louis-Philippe was close to the liberal opposition. But Charles was always unfailingly polite and respectful to Louis-Philippe despite their differences of opinion, and Louis-Philippe had returned the friendliness.9

So when Orléans discovered the Four Ordinances on July 26 in his copy of the Moniteur, his reaction was despair. One of the duke’s children, 12-year-old François, wrote later that his father at first “said only: ‘They are crazy!’” Then, after a long silence, Louis-Philippe resumed his complaints: “They will have us exiled again. Oh! I have already been exiled twice! I don’t want any more of it. I am staying in France.”10

So when Orléans discovered the Four Ordinances on July 26 in his copy of the Moniteur, his reaction was despair. One of the duke’s children, 12-year-old François, wrote later that his father at first “said only: ‘They are crazy!’” Then, after a long silence, Louis-Philippe resumed his complaints: “They will have us exiled again. Oh! I have already been exiled twice! I don’t want any more of it. I am staying in France.”10

Right: Louis-Joseph Noyal after François Gérard, “Marie-Amélie, Duchesse d’Orléans, with her son the Duc de Chartres,” circa 1815-1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Equally horrified by the news was Louis-Philippe’s wife, Marie-Amélie. Born Maria Amalia near Naples, the Duchesse d’Orléans was the daughter of King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies. This made her the aunt of Marie-Caroline, the Duchesse de Berry — Marie-Caroline’s father, King Francis I, was Marie-Amélie’s brother. And seven years before Marie-Caroline married the Duc de Berry, Marie-Amélie married another French royal duke: Louis-Philippe. (Sorry, that’s a lot of Maries marrying.) The 1809 wedding of Marie-Amélie and Louis-Philippe, conducted while bride and groom were both in exile,11 proved to be a good match. Aside from her royal blood, Marie-Amélie was intelligent, well-educated, and kind. Her politics were more conservative than Louis-Philippe’s were, and her deep Catholic piety was “foreign” to him, but Marie-Amélie did not heavily engage in politics — she embraced the “traditional [role] of wife and mother.” And that she did very well: by 1830, the two of them had eight living children.12

But Louis-Philippe had two prominent women in his household at Neuilly, not just his wife. Which means I’m excited to finally be able to introduce you to one of my favorite figures from this period, who’s been in the background of our narrative so far: Louis-Philippe’s younger sister Adelaide.

Below: Unknown artist after François Gérard, Madame Adelaide d’Orléans, sometime before 1848. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Born in 1777, Adelaide was four years younger than Louis-Philippe, but the two were close their entire life. As children, both had been placed in the hands of their governess, Madame de Genlis, who had extremely unorthodox opinions on children’s education influenced by the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Louis-Philippe and his brothers — none of who survived to the Bourbon Restoration — were drilled from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily in literature, history, science, modern and classical languages, math, and physics, many taught by Madame de Genlis herself. Even more unusually, she tried to cultivate moral and physical excellence through methods such as making the children sleep on wooden boards, work out in a gymnasium, and walk around in shoes weighted with lead to try to build endurance. The Orléans children were also educated in a group with several other children from different social ranks, including several orphans.13

Born in 1777, Adelaide was four years younger than Louis-Philippe, but the two were close their entire life. As children, both had been placed in the hands of their governess, Madame de Genlis, who had extremely unorthodox opinions on children’s education influenced by the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Louis-Philippe and his brothers — none of who survived to the Bourbon Restoration — were drilled from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily in literature, history, science, modern and classical languages, math, and physics, many taught by Madame de Genlis herself. Even more unusually, she tried to cultivate moral and physical excellence through methods such as making the children sleep on wooden boards, work out in a gymnasium, and walk around in shoes weighted with lead to try to build endurance. The Orléans children were also educated in a group with several other children from different social ranks, including several orphans.13

As a girl, Adelaide didn’t go through quite the same boot camp — probably a mixed blessing — but she was far from neglected and learned a range of skills from Madame de Genlis and other tutors. Historian T.E.B. Howarth describes the adult Adelaide as “a strong character”:

A woman of courage and decision, definite in her likes and dislikes, much less sensitive to other people’s opinions than Louis-Philippe and with a wit and intelligence that enabled her to converse on public affairs to the admiration of men of the mental caliber of Talleyrand and Benjamin Constant.14

Adelaide would never marry. As a child, there were discussions of an arranged marriage with her cousin, the Duc d’Angoulême, but it never came to pass. Driven into exile by the Revolution at age 15, Adelaide would not be restored to the full Orléans wealth and social status until the Bourbon Restoration in 1814. By this point, she was 37. In the views of contemporary society, Adelaide was an “old maid” with very little chance of being married despite her elite position. Now, very little is not none, and in 1817 Adelaide became extremely close with her brother’s aide-de-camp Raoul de Montmorency, a young aristocrat 13 years her junior. What happened between them is difficult to determine, but portions of Adelaide’s diary from the time have been ripped out, and subsequent entries betray “deep emotional distress.” Eventually Raoul would resign his position, citing “unspecified but powerful reasons” with which Louis-Philippe “was forced to concur.” Whatever had happened, Adelaide came out of it with a newfound devotion to God — and to her brother, from whom she was rarely separated. By 1830, she was 52 years old, and Louis-Philippe’s closest confidant: “He listened constantly to her advice, [and] never took a political decision without consulting her.”15

As France’s crisis of 1830 boiled over in late July 1830, Adelaide had advice for her brother very different from his own instincts. While the duke saw the danger posed to their family by the Four Ordinances, Adelaide saw the opportunity. He sat on his divan and fretted; she loudly complained about Charles’s action. At dinner on the night of Monday July 26, Adelaide went further: she advised Louis-Philippe to go immediately to Paris and rally opposition to the Four Ordinances with himself as leader.16

As France’s crisis of 1830 boiled over in late July 1830, Adelaide had advice for her brother very different from his own instincts. While the duke saw the danger posed to their family by the Four Ordinances, Adelaide saw the opportunity. He sat on his divan and fretted; she loudly complained about Charles’s action. At dinner on the night of Monday July 26, Adelaide went further: she advised Louis-Philippe to go immediately to Paris and rally opposition to the Four Ordinances with himself as leader.16

Right: Louis Hersent, François d’Orléans with his aunt, Madame Adelaide d’Orléans, unknown date. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Such bold action was not in the cautious Louis-Philippe’s temperament. The duke stayed at Neuilly and worriedly monitored developments from Paris. Monday, July 26 was quiet, but late that night the first rioting began. The young François d’Orléans was sent to school in Paris on Monday and Tuesday; on Tuesday François encountered soldiers posted around the city, and groups of young men “discussing… incidents, true or not, which had occurred during the day.” Back at Neuilly, Louis-Philippe stayed put and welcomed visitors, including an elderly English lady he had known during his exile, which may not have been an encouraging reminder for a man contemplating being forced into exile again. At night, the Orléans household could hear distant gunshots from the street-fighting a few miles away in Paris.17

Wednesday, as we’ve seen, was the decisive day of the revolution. That was true for the street fighting in Episode 42 that left Marmont’s army exhausted, and for the political debates in Episode 43 that left men like Jacques Laffitte prepared to join the revolution. It was also decisive in a different way for Louis-Philippe, who kept his children home Wednesday as fighting intensified. The sounds of cannons and rifles were clearly audible all day, and a stream of visitors brought updates — often contradictory — on the fighting. As we saw last time, many observers in Paris thought that Marmont’s soldiers were winning on Wednesday, and by dinner Louis-Philippe began to worry that Charles would send soldiers to arrest him. Adelaide’s reaction was entirely different of course — she was heard to murmur, “If only I carried a sword!” But she was concerned for her brother’s safety, too, and late that night the duke left the main house at Neuilly to go into hiding. His hiding place — an outbuilding on the estate used for growing silkworms — was kept a close secret; years later, Louis-Philippe’s son François wrote that “his movements were rigorously concealed from us” and that “I never learnt what they were, even in later days.” From this hiding spot, Louis-Philippe was now safe — but also out of the way.18

Unknown artist, “View of the Château de Neuilly-sur-Seine,” circa 1751-1848. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Believe nothing”

As the revolution escalated on Tuesday and Wednesday, Charles X stayed put in Saint-Cloud. The king’s court had a fixed daily routine, and he largely kept to it despite the unrest. Charles typically rose early, had the day’s newspapers read to him, ate breakfast, and then granted informal audiences to certain members of the royal court. Afterwards, Charles attended Mass, then often passed the afternoon with some combination of resting, playing with his dogs, and relaxing in the royal parks. At 5 p.m. he played with his grandchildren. Then dinner, the evening game of whist, and finally bed around 11 p.m.19

On Tuesday, July 27, the only major break from this routine was that there were many fewer newspapers to read to the royal ears, on account of the First Ordinance’s censorship. When Charles received courtiers that morning, the Duchesse de Gontaut — the royal governess, whose memoirs are one of our major sources for Charles’s actions at this time — was again among them. In this case she was not making a social call, but acting as a go-between. She had just been visited by a certain Dr. Bertin, who had treated both Gontaut’s son and Polignac. Bertin was here as a messenger with a letter from the prime minister — sent because Polignac “was afraid a courier in the royal livery might be stopped” by hostile crowds. Despite the importance of his missive, Charles initially refused to see the doctor himself, instead letting Gontaut pass the letter along. Royal protocols did not allow just anyone into the king’s august presence.20

The letter, as Gontaut relates it in her memoirs, told the king that Polignac had things under control:

It is my duty to say to the King that, surrounded as he is by alarmists who wish to frighten him, I most earnestly entreat him to believe nothing but what he hears from me and my reports, which will be sent to him hourly ; we shall soon get to the end of exaggerated rumors of what is, after all, but a mere riot. If I am mistaken in my conclusions, I will give your Majesty my head as a penalty.21

And then Charles proceeded to take Polignac’s advice. Told not to listen to anyone but his prime minister, Charles gave instructions Tuesday morning that he was not to be disturbed. Three foreign ambassadors — from England, Russia, and the Pope — all visited the palace to warn Charles about the escalating situation in Paris; all of them, Gontaut says, were turned away without an audience.22 In the late morning, Charles attended mass as usual. Afterwards, the king had Marshal Marmont stop by to give him a message: “It appears that there is some concern for the tranquility of Paris. Go there, take command, and see Prince Polignac on your way. If all is in order in the evening, you may return to Saint-Cloud.”23 I covered the aftermath of that conversation from Marmont’s perspective in Episode 42.

Above: Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin, portrait of Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont, Marshal of France, 1837. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: Thomas Lawrence, “Portrait of Caroline Ferdinande of Bourbon-Two Sicilies (1798–1870), Duchess of Berry,” 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The king continued to remain in periodic contact with Polignac, including an in-person meeting first thing Wednesday morning to sign a decree putting Paris under Marshal Marmont’s martial law.24 But as Polignac had instructed him, the king refused to talk to anyone else about the fighting. The Duchesse de Berry, frustrated at the waiting, told Charles, “What a misery it is to be a woman!” and offered to go to Paris herself to rally the troops; she was told to stay where she was and wait. When Gontaut offered to take the king to her rooms, which looked out toward Paris, and observe the fighting through a spyglass, Charles refused.25 Back in Paris, Marmont sent multiple dispatches to the king, some requesting urgent instructions, but frequently was left waiting many hours for a royal update.

The king continued to remain in periodic contact with Polignac, including an in-person meeting first thing Wednesday morning to sign a decree putting Paris under Marshal Marmont’s martial law.24 But as Polignac had instructed him, the king refused to talk to anyone else about the fighting. The Duchesse de Berry, frustrated at the waiting, told Charles, “What a misery it is to be a woman!” and offered to go to Paris herself to rally the troops; she was told to stay where she was and wait. When Gontaut offered to take the king to her rooms, which looked out toward Paris, and observe the fighting through a spyglass, Charles refused.25 Back in Paris, Marmont sent multiple dispatches to the king, some requesting urgent instructions, but frequently was left waiting many hours for a royal update.

Instead, as Paris burned, Charles was focused on acting like everything was normal. “It was considered of great importance in the royal apartment that no signs of uneasiness should appear,” Gontaut wrote. All the normal routines of the royal court went on as normal, to the increasing frustration of many courtiers who sensed the mounting crisis. In her memoirs, Gontaut says that she was scandalized, but that “the King told me afterwards that he only tried to seem calm, because this was thought best.”26

Understanding why exactly this was Charles’s priority confused many people at the time, and it can seem incomprehensible two centuries later. So to try to understand his mindset, it’s time to talk a bit more about the institution of the French royal court. Which is in turn going to require us to rewind all the way back to 1789.

Meet the courtiers

Before the French Revolution changed everything, France was an absolute monarchy. At least, that was the theory. In practice, of course, no man rules alone. Kings like Louis XVI had official ministers to handle the affairs of state, of course, but on a day-to-day basis they were also surrounded by huge numbers of nobles who held positions in the royal household, not the government. In 1789, the French government ministries employed around 660 officials; the maison du roi, the King’s household, employed around 2,500. Some of these were commoners, but many were from the top rungs of the aristocracy.27

The House of Bourbon considered themselves the most dignified and important royal family in the world, and adopted the principle that “The King of France cannot be served like a private person by ordinary servants… the more you raise your entourage, the more you raise yourself.” Their servants would be dukes and counts. In return for working as a servant for the king, though, some of these aristocrats acquired an incredible power: access to the king. Even government ministers would use favored courtiers to get the king to back their preferred policies. Other officials controlled the king’s social relations and his private budget; their jobs were considered so powerful that they were split in four, rotating between different people every quarter or year. Slightly lower-ranked servants, staffed from the lesser nobility or richer bourgeoisie, might have even more power because they were more trusted; they acted as diplomatic intermediaries and could help select royal mistresses.28

And despite all the turmoil of the Revolution and the Empire, when Louis XVIII returned from years of exile to reclaim the throne of France in 1814, the Bourbon court was there. Without being officially summoned, court officials from the ancien régime left their estates to attend the king at the Tuileries Palace in Paris. Where former court officials had died over the years, sometimes their sons showed up instead to continue their fathers’ duties — many of these court roles were hereditary.29

But while many of the names and jobs were the same, the court itself was different in ways both subtle and profound. It was a vestigial institution, held over from the ancien régime, but now living alongside a new, modern constitutional monarchy where real power was held by government officials, not courtiers. There are plenty of stories from the Restoration about the powerful influence that courtiers supposedly exerted, but plenty of men served as both court officials and government ministers, and these men tended to admit they had more influence as ministers than as courtiers.30

Why, then, did a royal court persist alongside constitutional government? The answer is partly just tradition, but there’s more to it than that.

In a monarchy, as we’ve seen, access to the king was tremendously powerful. Equally powerful in Early Modern France were the high nobility, who led repeated rebellions against 16th and 17th Century French kings. By 1814, there was little danger of French aristocrats leading armed rebellions against the monarchy — but kings like Louis and Charles were intimately concerned with making sure France’s elite was closely bound to their regime. So they invited this elite to serve them at court.

One sign of the popular belief that courts were a good thing for a monarch was that Napoleon created one from scratch after proclaiming himself emperor. The Revolution had abolished the French court, so Napoleon didn’t have to have one. But he chose to make one anyway, borrowing what he liked from the Bourbons and adding his own twists.31

So under the Bourbon Restoration, the royal court served multiple purposes. It satisfied the powerful desire of French elites for titles and honors — especially since holding a court position came with a special military-style uniform that the courtier would wear to align with men’s fashion; a court appointment got you a fashionable uniform without having to actually join the Army.32 The celebrated author Madame de Staël wrote at this time that “the first article of the Rights of Man in France is the necessity for every Frenchman to occupy a public office.”33 With positions in the military and civil service now mostly open to men of talent regardless of birth, the royal court provided an outlet where the aristocratic elite could dominate — 86 percent of the honorary Gentlemen of the Bedchamber under the Restoration had noble titles.34

But bringing this many powerful and ambitious men and women into close proximity with the kingdom’s ruler also presented real political dangers. So besides binding elites to the king, the institution of the royal court served to neuter them. As Philip Mansel, the preeminent historian of French royal courts in this era, notes, “While they were in waiting, court officials were so busy being servants that they hardly had the opportunity, or desire, or courage, to act as politicians and try to manipulate their masters.” On top of that, the court used a rigid set of rules and traditions to simultaneously provide access to the king and to limit it.35 Courtiers could have the honor of being in the room with the king — but were terrified of breaking tradition to speak about politics.

For example, Amédée-Bretagne-Malo de Durfort, the Duc de Duras, had the right to enter the king’s room and address him from his position as a First Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Duras thought the Four Ordinances were a mistake. But despite having both means and motive to speak out, the duke waited several days before approaching the king one morning and — “after long hesitations” — urging compromise.36

For example, Amédée-Bretagne-Malo de Durfort, the Duc de Duras, had the right to enter the king’s room and address him from his position as a First Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Duras thought the Four Ordinances were a mistake. But despite having both means and motive to speak out, the duke waited several days before approaching the king one morning and — “after long hesitations” — urging compromise.36

Above: Unknown painter, “Amédée Bretagne Malo de Durfort, Duc de Duras,” circa 1789-1838. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The fact that the king’s First Gentleman of the Bedchamber was urging Charles to back down explains a huge part of the note that Polignac sent the king on Tuesday, July 27. When he said Charles was “surrounded… by alarmists who wish to frighten him,” he meant the court. The Duc de Duras was far from the only courtier who opposed the Four Ordinances. Despite being a group of right-wing aristocrats, Charles X’s courtiers were generally not big fans of Jules de Polignac and his ultra-royalist ministry. These men were conservative royalists, yes, but they liked the stable order of the Bourbon Restoration, and generally wanted to keep it the way it was — not rock the apple cart with drastic measures like the Four Ordinances. Even Polignac’s own brother Armand, who held the court title of Grand Squire of France,37 opposed Jules’s ministry.38

The entire court system had been designed to preempt the danger of courtiers influencing the king. But as the crisis escalated, many of the men and women around Charles at Saint-Cloud became convinced that the king didn’t understand. He faced not the hypothetical danger of court influence, but the very real danger of Parisian revolution. And if they didn’t tell him that, who would?

Victor-Jean Nicolle, “Courtyard of the Chateau de Saint-Cloud,” sometime before 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Vitrolles

Charles ignored the Duc de Duras on Tuesday morning, just as he had ignored the Duchesse de Gontaut’s concerns on Monday morning. But on Wednesday came a third courtier, one the king would have a harder time dismissing. Baron Eugène de Vitrolles was a courtier, but he was also a former minister and a member of Charles’s Council of State. Vitrolles was an ultraroyalist who Charles had sought out for advice before — though Vitrolles’s ultraroyalism was cautious and practical, in a way that put him at odds with the more idealistic Polignac. Like everyone else, Vitrolles had been in the dark about the Four Ordinances, but he was a perceptive man. We saw him briefly in Episode 39, when he attended court on Sunday July 25, noticed the ministers acting suspiciously, and immediately guessed they might be about to launch a coup. Vitrolles had begged the ministers to “reflect carefully before you take decisive steps,” but his advice was not taken.

Since that time Vitrolles had observed rising tensions in the street. He saw gathering crowds of important people at the house of his neighbor, the opposition leader Jacques Laffitte. And he had a conversation on Tuesday with an envoy from another opposition leader, General Étienne Gérard. This envoy told Vitrolles that the revolution was in danger of overthrowing the government — which Gérard didn’t want — and begged him to intervene with the king to secure concessions. At the time, Vitrolles waved off the warning, but by the next day, he had become more worried. He tried to see Polignac but was turned away. So Vitrolles summoned his carriage at around noon on Wednesday — “at the moment,” he wrote later, “when the insurrection was igniting like a vast wildfire.” He was going to Saint-Cloud.39

Vitrolles arrived at the chateau around 1 p.m., and noticed the whole court seemed to be on edge. He asked the Duc de Duras if he could speak to the king, and was told Charles would be happy to see him next. Then he sat and cooled his heels for nearly an hour while Charles chatted with his steward about staffing issues; the sounds of cannon fire from Paris were audible in the distance.40

When he was finally ushered in to the royal presence, court protocol dictated that Vitrolles was supposed to let the king speak first, and only speak when spoken to. It was one of those countless rules designed to keep courtiers out of politics, and let the king steer the conversation wherever he wished. But Paris was burning and Vitrolles was upset, so the old émigré threw decorum out the window and spoke first. In “lively language,” Vitrolles told the king what he had seen in Paris, and what he had heard from Gérard’s envoy. Charles heard him out, but refused to budge. For one thing, it was a matter of principle: The Four Ordinances were legal, and a king could never negotiate with rebels under arms. If they surrendered, Charles would be merciful. But more importantly, Charles was convinced he didn’t need to negotiate. He gestured to reports sent to him that morning and told Vitrolles that Marmont had everything in hand. At that very moment, Charles added, rebel leaders like Lafayette and Laffitte were being arrested, and a court-martial was prepared to summarily execute any rebels caught under arms. “A small number of examples,” Charles hoped, “would put out the fire of the revolt.”41

Vitrolles, in his memoirs, admits that the king’s self-assurance and apparent knowledge shook his confidence. But then, as Vitrolles prepared to leave, the king asked him a question: Should Charles go to Paris? The baron replied that he would have advised Charles to go to the Tuileries, except that the king had just told him there was a court-martial there handing out summary executions. Charles should keep well away from any such unpleasant business, Vitrolles said, and let other men take responsibility.42

Now the thing is, none of that was true. Marmont’s soldiers had only just begun the day’s brutal street fighting, which would not go well for them. While many opposition leaders expected to be arrested, none of them had been. And though Marmont had dictatorial powers in Paris, no summary courts-martial had been held.

The obvious source for the mistaken reports that Charles had on his desk is Polignac. We know what Marmont’s reports to Charles on Wednesday morning had said — that rebels were “forming again, more numerous and more threatening than before.” That’s very different in tone from the confidence Charles conveyed that things were in hand. Polignac had, in fact, given Marmont a list of opposition deputies to be arrested, but at the very moment Charles was talking to Vitrolles, Jacques Laffitte and four other opposition leaders had walked into the Tuileries to negotiate and had been granted safe passage by Marmont. Polignac had spearheaded the declaration of martial law, and had advocated harsh measures such as firing on disloyal soldiers. It seems likely that Polignac had told Charles what he planned to do that day, and that Charles in turn told Vitrolles that those measures had already happened. Vitrolles notes that he spoke to the king for nearly two hours without any interruptions from aides bringing new information. “It was unfortunate,” Vitrolles wrote acidly in his memoirs, “that our princes were not trained in… prompt decision-making.”43

Col. Komierowski

Very soon after Vitrolles left, updated news did finally arrive from Paris. Escorted by a squad of 25 lancers, Col. Louis Komierowski galloped up to Saint-Cloud bearing an important message from Marmont. The marshal had met with Laffitte and other opposition leaders and heard their demands: if Charles first rescinded the Four Ordinances and dismissed the Polignac ministry — and only then — they would call for the people to lay down their arms. Marmont had refused to commit to such a plan himself, but promised to forward it on to the king. After hastily describing their demands in a letter to Charles, Marmont added commentary: “I think it is urgent that your majesty exploit without delay the overtures which have been made.”44

Komierowski was ushered in promptly to see Charles. The king read Marmont’s letter, and then asked the colonel to wait around for an answer. Komierowski went back into the antechamber; to his military eye, it was “business as usual” for the assembled courtiers. After 20 minutes, the colonel grew frustrated and approached the Duc de Duras. It was urgent that he get a response from the king, Komierowski said. The duke told the colonel he was going to have to wait — according to the rules of court etiquette, no one could return to the royal presence so soon after being dismissed. Seething, Komierowski continued to wait until he was finally summoned again. But the king’s orders had hardly been worth waiting for. Charles did not accept the politicians’ offer, nor did he make a counter-proposal. Instead, he told Marmont to “assemble his troops, maintain his position, and operate by masses.”45

Given what Charles had just told Vitrolles, it’s perhaps not surprising he didn’t suddenly agree to the liberals’ demands, despite the fresh information from Komierowski and Marmont about the hard, bloody fighting in Paris. But if the king had possibly been wavering, he had his backbone stiffened. While Komierowski was waiting, Charles met with his son, the Duc d’Angoulême, and his daughter-in-law, the Duchesse de Berry — both hard-liners. And it seems that in this time he also got a second message from Paris — from Polignac. The prime minister later said that: “I simply wrote to His Majesty, as I had agreed with the Marshal, to inform him of the purpose of the visit of Messrs. Laffitte and Casimir Périer.” But Marmont in his memoirs sharply disagreed with the implication that he and Polignac were on the same page. Instead, he was convinced that Polignac urged Charles to ignore Marmont’s advice and keep fighting. Charles did.46

And so things stood as we come back to where we started: Charles and his courtiers playing cards Wednesday night, pointedly ignoring the sounds of battle off in the distance. As tricks were taken in Saint-Cloud, Marmont’s great assault columns were staggering back through the darkened streets to the Tuileries. The king’s big talk that afternoon about imminent victory had been just that — talk.

Above: “But Sire, give orders, the blood is flowing and you can stop it,” a uiformed soldier says to King Charles X, kneeling in church. “After Mass,” the king replies. Caricature by H. Fournier, 1830. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Sémonville

As Thursday dawned, Paris seemed quiet. The liberal Duc de Broglie, walking under the overcast early morning sky with Charles de Rémusat, was moved to declare: “It’s all over.” But this was a pause, not the end. Over the night, Parisians had thrown up hundreds more barricades, all across the city. One visitor approaching the city from the north described encountering a barricade every 30 feet, even in peaceful areas of the city that had seen no fighting. But the barricades that had been so decisive the day before were now — for the moment — useless. Marmont’s troops were huddled around the Tuileries, demoralized and exhausted. They could not have made more assaults even if Marmont had wanted them to, which he did not.47

The city was still quiet around 7:30 a.m. when Marquis Charles de Sémonville arrived at the Tuileries. Sémonville was, in the words of historian Philip Mansel, a “brilliant, supple politician who had served every regime since 1789 and knew more about monarchies and revolutions than most of his contemporaries.” He was moderate and practical, and in a position of authority — the marquis was the grand référendaire of the Chamber of Peers, charged with acting as an intermediary between the Chamber and the King. Now, after two days of revolution, and fearing things might escalate further, Sémonville was here to try to fix things.48

The city was still quiet around 7:30 a.m. when Marquis Charles de Sémonville arrived at the Tuileries. Sémonville was, in the words of historian Philip Mansel, a “brilliant, supple politician who had served every regime since 1789 and knew more about monarchies and revolutions than most of his contemporaries.” He was moderate and practical, and in a position of authority — the marquis was the grand référendaire of the Chamber of Peers, charged with acting as an intermediary between the Chamber and the King. Now, after two days of revolution, and fearing things might escalate further, Sémonville was here to try to fix things.48

Left: Honoré Daumier, caricature of Charles Louis Huguet de Semonville, 1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

He went first to Polignac and the other ministers, who had spent the night in the Tuileries, and loudly told the men they had to revoke the Four Ordinances and resign. As Sémonville tells it, many of the ministers seemed to agree with him, but Polignac remained cool and calm, and insisted such an action was beyond any of them. Only Charles could take such an action — and of course, as we’ve seen, Polignac had been advising Charles to do no such thing.49

With Polignac unmoved, Sémonville turned to Marmont, who had witnessed the entire argument. “Scarcely expecting to be taken seriously,” Sémonville proposed that Marmont launch his own coup — put the ministers under arrest and end all this himself. In Sémonville’s account, he thought Marmont was actually considering accepting, when Polignac and the ministers suddenly re-appeared. They were headed to Saint-Cloud, to meet en masse with the king.50

And now we get a dose of slapstick comedy in the middle of this epic tragedy. On hearing that Polignac was headed to Saint-Cloud, the 71-year-old Sémonville ran for the doors, where Polignac’s carriage was waiting to take him to visit the king. Sémonville jumped in, threw Polignac’s briefcase out the window, and took off for Saint-Cloud. Moments later, Polignac himself ran outside, right as a second carriage pulled up, intended for Sémonville. And so the two men raced the six miles west to Saint-Cloud, in each other’s carriages, finally arriving at the courtyard almost simultaneously.51

When the dust settled, Charles, Sémonville, and Polignac were all in the room together — and the yelling began. Specifically, the king and Sémonville “angrily confronted each other,” with Sémonville trying to persuade Charles to understand just how much danger the revolt in Paris actually posed. Marmont’s situation was extremely perilous. Charles had to withdraw the ordinances and appoint a compromise ministry, he said. The heated discussion, Sémonville later wrote, was “long and painful” and definitely violated court protocols. By the end of it, Charles “slouched at his desk, his head in his hands.” Charles was willing to issue a general amnesty to the rebels, but hesitated to go further even as Sémonville “threw himself at the king’s feet,” weeping and begging. Neither was the king persuaded by the more cynical argument of his naval minister, Baron d’Haussez, who was also present. Haussez argued that Charles should absolutely negotiate — in order to buy time for him to raise fresh forces in the provinces and crush the rebels. But Charles did not want to compromise his royal dignity and negotiate with rebels under arms, however vehemently he was pressed. Desperate, he clung to a report from Marmont the night before: that the marshal felt he could hold his defensive positions around the Tuileries for at least three days. If he had three days, Charles appears to have thought, what was the cost of taking a little more time to consider things? He told Sémonville, in a low, “scarcely audible” voice, that he would talk about the matter with his ministers.52

And then it was 11 a.m., and Charles got up to go to Mass, because that’s what he did at 11 a.m. every day. As historian David Pinkney comments, “Revolution could not interfere with court routine.”53

After church, Charles convened with his ministers and his son, the Duc d’Angoulême, who he liked to consult for key decisions. These close advisors were split. Angoulême wanted to fight. Haussez continued to argue for negotiations, writing in his memoirs that he told the prince that “there are occasions when it takes more courage to give timid advice than to brave danger.” Angoulême tried to storm out of the room, but was called back by the king. The debate was still raging when everyone slowly became aware of a sound — someone was scratching at the door.54

It was one last bit of court etiquette: someone wanted in, but it was considered unacceptable to knock on the door of a room containing the king.55

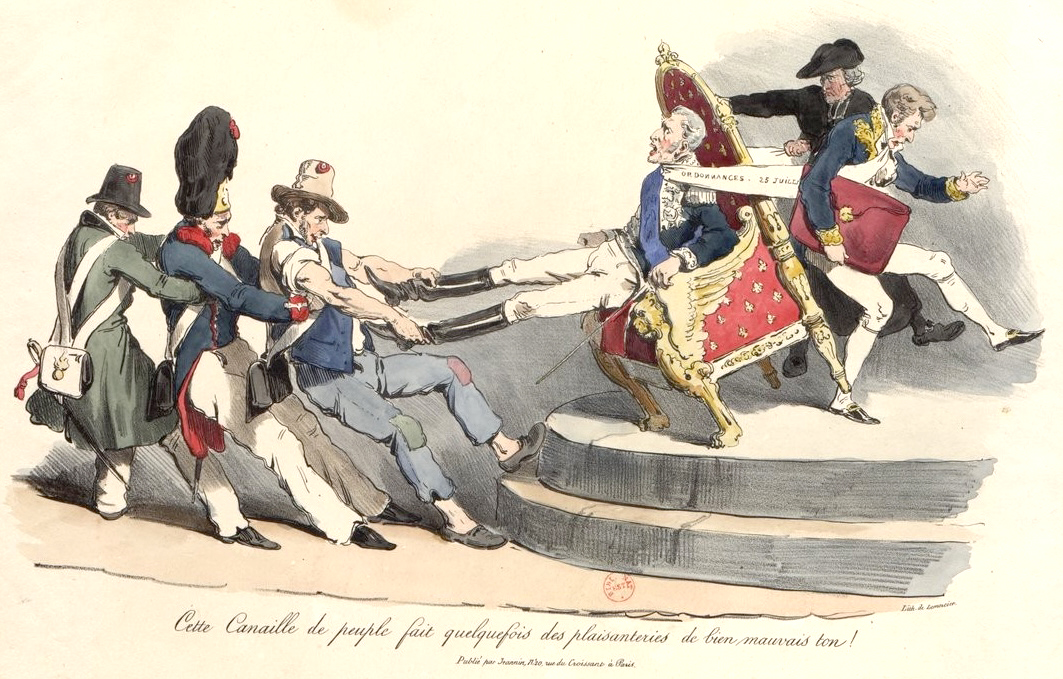

“This rabble of a people sometimes makes jokes in very bad taste!” exclaims Charles X, as his people drag by the feet to remove from the throne, while Jules de Polignac and a Jesuit have tried to hold him there by placing around his neck the “ordinances,” which strangle him. Caricature published by Jeannin, 1830. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The fall

The new arrival was ushered in: General Charles Coëtlosquet, sweaty and dirty, arrived after a frantic dash from Paris with sensational news. Marmont had been wrong. He could not hold the Tuileries for three days. His demoralized troops hadn’t even held it for three hours of fighting. The rebels had routed the royal army, taken the palace, and now were in complete control of the capital.56

It was a stunning development, and it seemed to strike Charles like a physical blow. Speaking with “great emotion,” the king compared his situation to his oldest brother, the guillotined Louis XVI:

Gentlemen, they force me to dismiss the ministers who have my confidence and affection, and replace them with men named by my enemies. I am in the same position as my unhappy brother in 1792, except that I have the advantage of having suffered for a shorter period of time… As for the monarch, his end will be the same.57

Only now, after losing everything, did Charles become willing to make concessions. He would fire his unpopular ministry. So let’s all congratulate France’s newest prime minister, Casimir de Rochechouart, Duc de Mortemart.

Mortemart came from a distinguished old aristocratic family, and had loyally served the Bourbons in roles including ambassador to Russia. But before that, Mortemart had served Napoleon, too. A man with one foot in the old France and one foot in the new, he was a member of the Chamber of Peers and a relative moderate — someone the king could accept, and who the opposition might accept, too. And he happened to be on hand at Saint-Cloud. But Mortemart was also currently sick, and tried to refuse the job. Charles had to guilt the duke into accepting, telling him: “What, you refuse to cooperate in measures which can save my crown, perhaps even my life and those of members of my family?” After all the debating, it was now about 5 p.m., some five hours after the fall of the Tuileries. And Charles continued to display no real urgency. Charles tasked Mortemart with going to Paris and telling opposition leaders that the ministry had been fired, and that Charles would withdraw the Four Ordinances. But, “hoping for a miracle,” Charles put none of this in writing. Mortemart, still feverish, refused to set off without getting everything written down, and the king refused to do so until finally backing down at 7 a.m. the next morning.58

Mortemart came from a distinguished old aristocratic family, and had loyally served the Bourbons in roles including ambassador to Russia. But before that, Mortemart had served Napoleon, too. A man with one foot in the old France and one foot in the new, he was a member of the Chamber of Peers and a relative moderate — someone the king could accept, and who the opposition might accept, too. And he happened to be on hand at Saint-Cloud. But Mortemart was also currently sick, and tried to refuse the job. Charles had to guilt the duke into accepting, telling him: “What, you refuse to cooperate in measures which can save my crown, perhaps even my life and those of members of my family?” After all the debating, it was now about 5 p.m., some five hours after the fall of the Tuileries. And Charles continued to display no real urgency. Charles tasked Mortemart with going to Paris and telling opposition leaders that the ministry had been fired, and that Charles would withdraw the Four Ordinances. But, “hoping for a miracle,” Charles put none of this in writing. Mortemart, still feverish, refused to set off without getting everything written down, and the king refused to do so until finally backing down at 7 a.m. the next morning.58

Above: Unknown artist, “Casimir Louis Victurnien de Rochechouart, Duc de Mortemart,” 19th Century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But though the fighting had died down, not everyone was quiet on the night of Thursday, July 29, 1830. Charles had waited too long, and decisions were happening without him. While Mortemart slept, a man was riding through the night for the Chateau de Neuilly with a vital question for the Duc d’Orléans.

“The Duc d’Orléans has declared himself”

The envoy was Adolphe Thiers, the energetic journalist we last saw in Episode 40 writing the Protest of the Forty-Four, the defiant journalists’ manifesto that had helped kick off the revolution. After this somewhat seditious act on Monday, fearing arrest, Thiers had gone into hiding. He had many talents, but physical courage was definitely not one of them. He didn’t emerge again until Thursday, as it became clear that Marmont had lost. That night, Thiers had argued energetically that it was time to replace Charles X with a more suitable monarch: Louis-Philippe.59

To persuade the people of Paris to accept the Duc d’Orléans as king, Thiers and his fellow journalist François Mignet wrote up a short manifesto to be printed all over Paris. It’s some of my favorite prose from this entire period of history, and it’s only eight sentences long, so I’ll just read the whole thing:

Charles X can never again enter Paris; he has caused the blood of the people to be shed.

The republic would expose us to frightful divisions; it would embroil us with Europe.

The Duc d’Orléans is a prince devoted to the cause of the Revolution.

The Duc d’Orléans has never fought against us.

The Duc d’Orléans was at [the Battle of] Jemmapes.

The Duc d’Orléans has carried the tricolor under fire; the duc d’Orléans alone can carry it again; we want no others.

The Duc d’Orléans has declared himself; he accepts the Charter as we have always wanted it.

It is from the French people that he will hold his crown.

The details of Louis-Philippe’s past military service in the French Revolution aside, some of these statements are extremely contentious, to say the least. Would declaring a new French Republic actually “expose us to frightful divisions” and the possibility of foreign invasion? Just how devoted to “the cause of the Revolution” was Louis-Philippe? We’ll talk about those more next episode, because as debatable as they might have been, there was one statement in particular where Thiers was, to put it bluntly, lying: “The Duc d’Orléans has declared himself.” Thiers knew full well that Louis-Philippe had done no such thing. That didn’t stop him from sending his manifesto off to get printed and plastered all over Paris — unlike Charles, Thiers knew how to take decisive action. But politicians like Jacques Laffitte knew there was only so far audacity could take them. If they were going to put Louis-Philippe on the throne, they were going to need the duke on board.60

And so, with a letter of recommendation from Laffitte in his pocket, and the Paris printing presses humming to life behind him, Thiers set out on his midnight ride. It wasn’t especially glamorous — the diminutive Thiers was too small to sit on a full-sized stallion, and so instead rode a pony. And he had to stop at every single barricade he passed along the way, negotiate his way past, and then often be lifted bodily over the barricade, pony and all. It wasn’t until mid-morning on Friday that Thiers finally reached Neuilly on his urgent mission.61

The duke was nowhere to be seen. Marmont’s retreating army had streamed past the gates of Neuilly as they fled Paris on Thursday afternoon, and the Orléans all agreed that Louis-Philippe should not be available to be seized as a hostage by some enterprising soldier. He had left his initial hideout in the silkworm house, and retreated early Friday morning to another of his houses, located on the far side of Paris. When Thiers arrived, he found only the Orléans women, Marie-Amélie and Adelaide, who refused to tell him where the duke was. But they listened as Thiers told the two noblewomen that it was time for Louis-Philippe to claim the throne. If the duke hesitated, Thiers said, then Bonapartists or republicans might seize the initiative. Charles still had forces at his disposal. If Louis-Philippe acted now, he could take the thrown with a “representative monarchy,” one that combined a royal bloodline that could appease the crowned heads of Europe with liberal ideas that would be acceptable to the Parisian rebels. “I cannot hide from you,” Thiers concluded, “that there will still perhaps be great dangers to surmount…. The Duc d’Orléans must decide. The destiny of France must not be left hanging in the balance.”62

The conservative Duchesse d’Orléans was horrified at the attempt to persuade her husband “to be disloyal to Charles.” But Adelaide, more liberal and more aggressive than her sister-in-law, took Thiers’s argument seriously. This was both a massive risk and a massive opportunity for her family, and with courage and insight, Adelaide saw a way to thread the needle. Without waiting for her brother, Adelaide told Thiers that she would commit herself:

If you think that the adhesion of our family can be of use to the revolution, we give it gladly. A woman is nothing in a family. She can be compromised. I am ready to go to Paris. What happens to me there is in God’s hands. I will share the fate of the Parisians.

Louis-Philippe could always disavow his sister’s actions. But the presence of an Orléans princess in Paris was enough for the Orléanist politicians to act. As Thiers prepared to rush back to the city with the news, he told Adelaide she had made the right decision: “Today, Madame, you have gained the crown for your house.”63

Next time, we will see if Adolphe Thiers was right. Adelaide d’Orléans will come to Paris. So will the Duc de Mortemart. There, the politicians and the people will engage in one final struggle for power. Please join me for Episode 45: The July Revolution.

-

Marie Joséphine Louise, Duchesse de Gontaut, Memoirs of the Duchesse de Gontaut: Gouvernante to the Children of France During the Restoration, 1773-1836, vol. 2, tr. J.W. Davis (London: Chatto and Windus, 1894), 159. Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 215. ↩

-

Comtesse de Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne: 1820-1830, Vol. 3, ed. Charles Nicoullaud (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 301-2. Gontaut, Memoirs, 159. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 356. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 214. ↩

-

Louis François Sosthènes de la Rochefoucauld, Duc de Doudeauville, Mémoires de M. de La Rochefoucauld, duc de Doudeauville [fils], Vol. 9 (Paris: Michel-Lévy frères, 1863), 127. Ambroise-Polycarpe de la Rochefoucauld, duc de Doudeauville, Mémoires de M. de La Rochefoucauld, duc de Doudeauville [père], Vol. 1 (Paris: Michel-Lévy frères, 1861), 293. Translation via Beach, Charles X of France, 215. ↩

-

Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 259. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 214, 359. David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 92-3. ↩

-

T.E.B. Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, Citizen-King (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1961), 136. Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 115-6, 134. ↩

-

François d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville. Memoirs [Vieux Souvenurs] of the Prince de Joinville, tr. Mary Loyd (London: William Heinemann, 1895), 32. ↩

-

Louis-Philippe was living in Great Britain. Marie-Amélie’s family had been driven out of their capital of Naples to their island holding of Sicily. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 44-5. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 19-21. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 20-1. Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, 116. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 45-7, 103-4. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 148. ↩

-

Joinville, Memoirs, 32-3. Price, The Perilous Crown, 164. Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, 145. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 164-5. Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, 145. Joinville, Memoirs, 34. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 213. ↩

-

This prohibition was far from ironclad, and Charles eventually changed his mind and met with Bertin. Gontaut, Memoirs, 149-50. ↩

-

Gontaut, Memoirs, 152. The king did allow one appointment this morning, to bestow a cardinal’s hat on an archbishop; Gontaut says the new cardinal had no news of Paris to share even had Charles asked, but he did not. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 100-1. ↩

-

I have not been able to ascertain the exact time Polignac visited Saint-Cloud Wednesday; my sources are clear it was “Wednesday morning” and that Polignac was back in Paris before 9 a.m, when Marmont found out about the martial law, which with the 10 kilometer distance implies the meeting took place no later than 8 a.m. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, The Court of France: 1789-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 8. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 9, 11, 97. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 94. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 162-3, 169. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 52-65. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 75-6. Mansel, The Court of France, 123. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Louis XVIII, Rev. ed. (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 202. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 133. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 156-60. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 172. ↩

-

French: Grand Écuyer de France. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 170, 189. ↩

-

Eugène François Auguste d’Arnaud, Baron de Vitrolles, Mémoires et relations politiques du Baron de Vitrolles, Vol. 3 (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1884), 375-80. ↩

-

Vitrolles, Mémoires et relations politiques, 380. Technically my sources don’t say what Charles spoke about with François Roullet de La Bouillerie, the intendent of the royal household; Charles Beach calls it “a relatively unimportant matter.” Beach, Charles X of France, 373. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 109-10. Vitrolles, Mémoires et relations politiques, 380-3. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 126. ↩

-

Vitrolles, Mémoires et relations politiques, 383-4. Beach, Charles X of France, 373-4. ↩

-

Vitrolles, Mémoires et relations politiques, 384. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 126. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 372. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 126. ↩

-

Procès des ministres de Charles X […] (Paris: Lequien, 1830), 136. Beach, Charles X of France, 372-3. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 127-8. ↩

-

Mansel, The Court of France, 132. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 132. ↩

-

Procès des ministres de Charles X […] 110-2. Beach, Charles X of France, 378. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 132. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 132. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 132. A second man, the Comte d’Argout, was also with Sémonville for much of this, but I have omitted him for simplicity. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 129, 133. Beach, Charles X of France, 379-80. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 133. ↩

-

Baron d’Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, Dernier Ministre da la Marine sous la Restauration, vol. 2 (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1897), 272-3. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 133. Beach, Charles X of France, 381. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 133. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 381. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 381. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 382-3. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 136-7. Price, The Perilous Crown, 162. ↩

-

Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, 147. Price, The Perilous Crown, 163. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 163. Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, 147. Price, The Perilous Crown, 146. Thiers supposedly suggested stamping the posters with the words, “from the government printers,” to give it the impression of a fait accompli. J.P.T. Bury and R.P. Tombs, Thiers, 1797-1877: A Political Life (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1986), 34. ↩

-

Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, 147. Price, The Perilous Crown, 165. Thiers was also accompanied by Ary Scheffer, an artist who worked for the Orléans family, and an officer of the Paris National Guard. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 167. Bury and Tombs, Thiers, 35. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 167. ↩