Supplemental 10: Et cetera, Wellington

This is The Siècle, Supplemental 10: Et cetera, Wellington

Welcome back at long last! It’s been far too long since the last episode, which is entirely my fault, for a very mundane reason: writer’s block. Work and other demands have sucked up most of my energy since March, and it’s been like pulling teeth to pull together my fascinating but hard-to-write next episode on religion in the Restoration. That will hopefully be done soon, but as June drew near to a close, I thought I had left your feeds barren long enough!

I do have a bonus episode in the can, the recording of my talk at April’s Intelligent Speech conference about French émigrés, but I’m hoping to be able to save that until our narrative has advanced just a little bit further. So instead, I have something special for you today: a look at the views of everyone’s favorite British general, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington.

I do have a bonus episode in the can, the recording of my talk at April’s Intelligent Speech conference about French émigrés, but I’m hoping to be able to save that until our narrative has advanced just a little bit further. So instead, I have something special for you today: a look at the views of everyone’s favorite British general, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington.

Right: Thomas Lawrence, “Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852),” circa 1815-16. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Wellington was intimately connected to France for much of his adult life, including obviously years fighting them on the battlefield, but also service as Britain’s ambassador to France, as commander of the Allied army of occupation, and as a diplomat to the Congress of Verona. Along the way he met and interacted with many of the characters we’ve met so far: Louis XVIII, the Comte d’Artois, Élie Decazes, Joseph de Villèle, the Duc d’Orléans, and others.

And Wellington wrote about all of them, in a nearly exhaustive stream of letters and memos touching almost every conceivable topic: high diplomacy, military minutiae, officers’ requests for promotion or honors, threats of lawsuits or duels to people with whom Wellington was feuding, and more. Altogether Wellington’s collected correspondence fills more than 20 very long volumes.

For the purposes of this episode, I’ve spent the last few days skimming through six of those volumes, totalling some 4,500 pages of Wellington’s correspondence from 1814 through 1825. I’ve selected and excerpted a few letters of particular interest that show the British general and statesman’s reflections on Restoration France, and will read them for you below, with added context.

While listening, it’s important to keep in mind Wellington’s politics and personality. He was a famously blunt man, extremely confident, and a prominent member of the Tory party. He was, in short, a conservative aristocrat who was partial to monarchy as the best and most stable form of government. He was also a fierce avocate for his country, and maintained a fair degree of a very typical British scorn for the French and their way of doing things.

If you’ve read correspondence from this period, or are familiar with the musical Hamilton, you may know that letter-writers sometimes closed their letters with long, flowery valedictions, like, “I have the honor to be your obedient servant,” or “Believe me yours faithfully.” Wellington, with his brusque, efficient manner, opts for a shorthand instead. For example, consider the letter written on Sept. 27, 1822, from foreign secretary George Canning to Wellington, which concludes, “I am, with great truth and respect, my Lord Duke, your Grace’s most obedient humble servant, George Canning.” Three days later, Wellington writes a letter to Canning, which concludes, “I have, &c., Wellington.”1

As one final note, because I’ll be jumping back and forth between extended quotations and my own voice giving context and analysis, I’ve added a sound effect to this episode to help guide you. The end of an extended quotation and the shift back to me will be marked by the following sound:

Part 1: Dangers

This first batch of letters were written in late 1814, while Wellington served as the British ambassador to France during the First Restoration. In them, Wellington addresses the British foreign secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, and the prime minister, the Earl of Liverpool, about what he sees on the ground in Paris, and what he hears from the court.

This first batch of letters were written in late 1814, while Wellington served as the British ambassador to France during the First Restoration. In them, Wellington addresses the British foreign secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, and the prime minister, the Earl of Liverpool, about what he sees on the ground in Paris, and what he hears from the court.

It is safe to say that Wellington is not particularly comforted by his observations. Though predisposed to like Louis, Wellington observes widespread discontent with the First Restoration, with critics to the government’s left, to its right, and even from its own members. Given enough time, Wellington believes, and Louis will stabilize his regime — but as we know, a few months later, Napoleon will capitalize on this discontent to escape from Elba, land in France, and seize power again.

Above: Thomas Lawrence, “Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (Lord Castlereagh),” circa 1809-10. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The political instability of 1814 France was sufficient that the British government began to worry for Wellington’s safety as ambassador. The concern was not just for Wellington as a man, or for the honor of Britain’s ambassador, but because Wellington was Britain’s best general, who would be expected to command its armies if France returned to war. One confidant informed the British government that should Louis fall, “not only will the Duke of Wellington be arrested, but his arrest will be justified to France, and in their judgment to Europe, by the circumstance of your having 60,000 men in Belgium, whom he is eventually to command.”2

But that just raised the question of what to do about these concerns. Simply recalling Wellington without a good excuse would have been seen for exactly what it was: a vote of no confidence by the British government in Louis’s regime, and possibly a self-fulfilling prophecy.

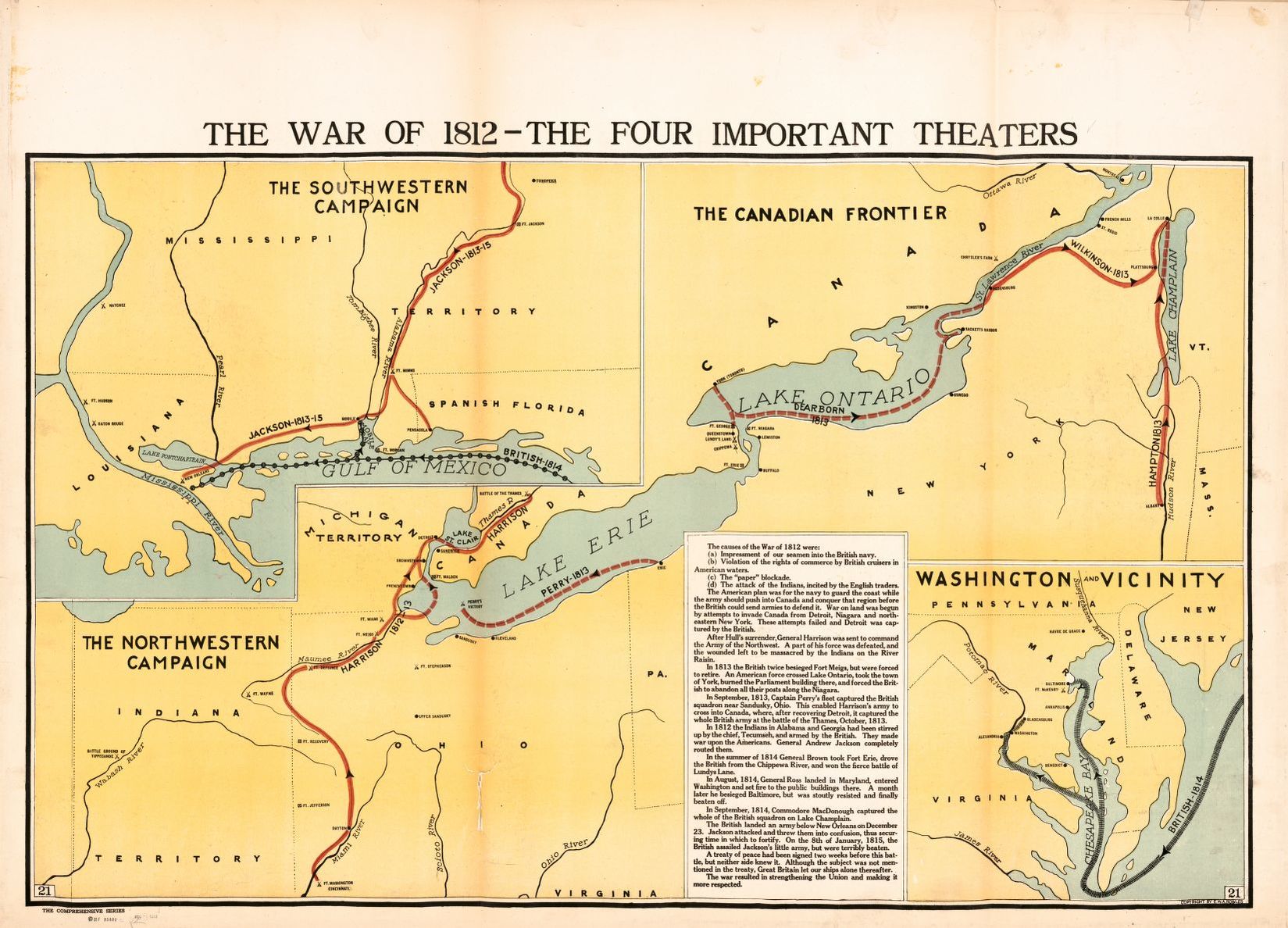

The British government had their own favorite alternative: sending Wellington to North America, to command the British forces in the ongoing War of 1812 against the United States. As we shall see, Wellington was not particularly keen on that idea.

Paris, Oct. 4, 1814. Wellington to Lord Viscount Castlereagh3

My lord,

There existed a good deal of uneasiness in the town in the course of the last week, which, however, was not manifested in any act of riot or disorder. The Jacobin party, and that attached exclusively to Buonaparte, were observed to be more than usually active; two libels against the King and the government were published and distributed, and reports of English influence, of the dangers to be apprehended from our position in the Low Countries, &c, were circulated in all the coffeehouses and public places.

There exists no doubt of the continued discontent of the military, and of those employed by the late government, for whom there is no employment under the present. The number of discontented is augmented by the immense number of persons ruined by the Revolution, who have all been accustomed to look to the restoration of the House of Bourbon as the end of their sufferings, and that the possession of their fortunes and of the honors and emoluments of the State would immediately follow. All this class of persons have been disappointed, and their wants are increased by the expenses which they have incurred to come to Paris to solicit employment; and they are as loud in their complaints of the want of firmness of the government as the Jacobin party and those attached to Buonaparte are in their censures of its want of other qualities.

The number of persons obliged to look for support from public employment and the resources of the public is immense, and far greater even in proportion to the size and population of France than in any other country; and all these are discontented, and ready to seize any opportunity to effect a change of any kind.

This situation of affairs must occasion constant uneasiness; but I entertain no doubt that if the King can carry on his government without any material difference of opinion with the legislature, he will gain time sufficient to establish it effectually.

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, Oct. 17, 1814. Wellington to Castlereagh4

My dear lord,

I have nothing particular to communicate to you from hence. There is certainly a good deal of uneasiness in the public mind at Paris, but I cannot discover any ground for it excepting the numbers of ruined and discontented persons there are in the town, who are certainly not discouraged from the execution of any scheme of mischief they may have in contemplation by the advice and example of their superiors. Even the Marshals and those in favor with the King do not scruple to express their dislike of the present system, and the shame they feel at finding themselves in the situation in which they are.

[Chief Minister] Blacas is inclined to make light of the danger, which I conceive consists for the present only in the chances of a sudden movement by a part of this body of discontented officers and employés, and its consequences. Hereafter the King will have some difficulties with his Legislature; but by that time he will have formed his army, it may be hoped.

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, Nov. 3, 1814. Wellington to Castlereagh5

My lord,

I was informed some days ago of the arrest of a General Dufourgues, with between thirty and forty other persons, General officers of the army on half-pay, and some of them [royal bodyguards]. The cause of their arrest has been kept secret… The truth is, however, that they were discovered in a conspiracy to destroy the Royal Family; and it is an extraordinary circumstance, and a symptom of the prevailing disposition, that these persona were quite unconnected with those known to be hostile to the King and his government…

I know that these [enemies of the King] consider these arrests a fortunate circumstance, and likely to blind the King to the real dangers of his situation; as Dufourgues and his companions could give no information whatever respecting any leading character…

The protest signed by Monsieur Ferrand, the Prince de Condé, and the Duc de Bourbon, against the ‘Charte Constitutionnelle,’ which has been published in the Morning Chronicle, has produced a great sensation here, and, connected with the recent appointment of Monsieur de Ferrand to the Ministry of Marine, is made use of by the discontented of all classes to prove the insincerity of the King. It certainly would have been more prudent not to have confirmed Monsieur de Ferrand in his office just at the moment that the Committee of the Chamber of Deputies made a report on a speech of his, in which he is accused of having intimated that the King entertained intentions inconsistent with what His Majesty had promised in his Royal Charter.

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, Nov. 7, 1814. Wellington to the Earl of Liverpool6

My dear lord,

I have received your letters of the 4th, and you will have seen… that I feel no disinclination to undertake the American concern; but to tell you the truth, I think that, under existing circumstances, you cannot at this moment allow me to quit Europe. You might do so possibly in March next,7 but now it appears impossible.

You already know my opinion of the danger at Paris. There are so many discontented people, and there is so little to prevent mischief, that the event may occur on any night; and if it should occur, I don’t think I should be allowed to depart. I have heard so frequently, and I am inclined to believe it.

But I confess that I don’t like to depart from Paris, and I wish the government would leave the time and the mode at my own discretion. To go to Vienna is a bad pretense; there is no good reason for going; and it would be better to be called to England for a few days to attend [a] court martial, and afterwards to be detained. It must likewise be observed that to go at all at the present moment is, in the opinion of the King’s friends, to allow him and ourselves to suffer a defeat, and we must not do that. I would likewise observe that I flatter myself I am daily becoming of more use to Lord Castlereagh here, and am acquiring more real influence over the government, and it would not answer all at once to deprive him of this advantage… I must confess that although I entertain a strong opinion that I must not be lost… they must not withdraw me in a hurry, and must not sacrifice the advantages which they would derive in leaving me here a little longer.

I send Lord Castlereagh a copy of this letter with those you have written him.

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Above: Thomas Lawrence, “Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool.” Before 1827. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Paris, Nov. 9, 1814. Wellington to Liverpool8

My dear lord,

The messenger for England was despatched so immediately after I received your letter of the 4th that I had not time to write to you upon many of the points which occurred to me upon it.

You cannot, in my opinion, at this moment decide upon sending me to America. In case of the occurrence of anything in Europe, there is nobody but myself in whom either yourselves or the country, or your Allies, would feel any confidence…

I have already told you and Lord Bathurst that I feel no objection to going to America, though I don’t promise to myself much success there. I believe there are troops enough there for the defence of Canada forever, and even for the accomplishment of any reasonable offensive plan that could be formed from the Canadian frontier. I am quite sure that all the American armies of which I have ever read would not beat out of a field of battle the troops that went from Bordeaux last summer, if common precautions and care were taken of them.

That which appears to me to be wanting in America is not a General, or General officers and troops, but a naval superiority on the Lakes. Till that superiority is acquired, it is impossible, according to my notion, to maintain an army in such a situation as to keep the enemy out of the whole frontier, much less to make any conquest from the enemy… The question is whether we can acquire this naval superiority on the Lakes. If we can’t, I shall do you but little good in America; and I shall go there only to prove the truth of [the] defence, and to sign a peace which might as well be signed now. There will always, however, remain this advantage [to my going], that the confidence which I have acquired will reconcile both the army and the people in England to terms they would not now approve.

In regard to your present negotiations, I confess that I think you have no right from the state of the war to demand any concession of territory from America. Considering everything, it is my opinion that the war has been a most successful one, and highly honourable to British arms, but from particular circumstances… you cannot then… claim a cession of territory excepting in exchange for other advantages which you have in your power…

I am sure you will excuse the liberty I take in giving you my opinion on this subject… I do so only that we may thoroughly understand each other before I undertake the concern.

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

E.W.A. Rowles, “The War of 1812 - the Four Important Theaters,” Dec. 1919. Public domain via Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Part 2: Crisis

That analysis by Wellington may have proven powerful and significant. At the time he wrote it, in early November 1814, Britain was making territorial demands on the American peace commissioners and contemplating escalating the war by dispatching their best general. That general responded with an unfavorable analysis of the war’s prospects, and threw cold water on the idea that Britain had a right to territory.

Six weeks after this missive, British negotiators signed the Treaty of Ghent on Dec. 24, 1814, which largely just returned both sides to the state of affairs before the war.

But while Wellington didn’t go to America, he did eventually give in and leave France. In late January 1815, he left Paris for Vienna, to be the new British representative at the ongoing Congress of Vienna — which I covered back in Episode 17.

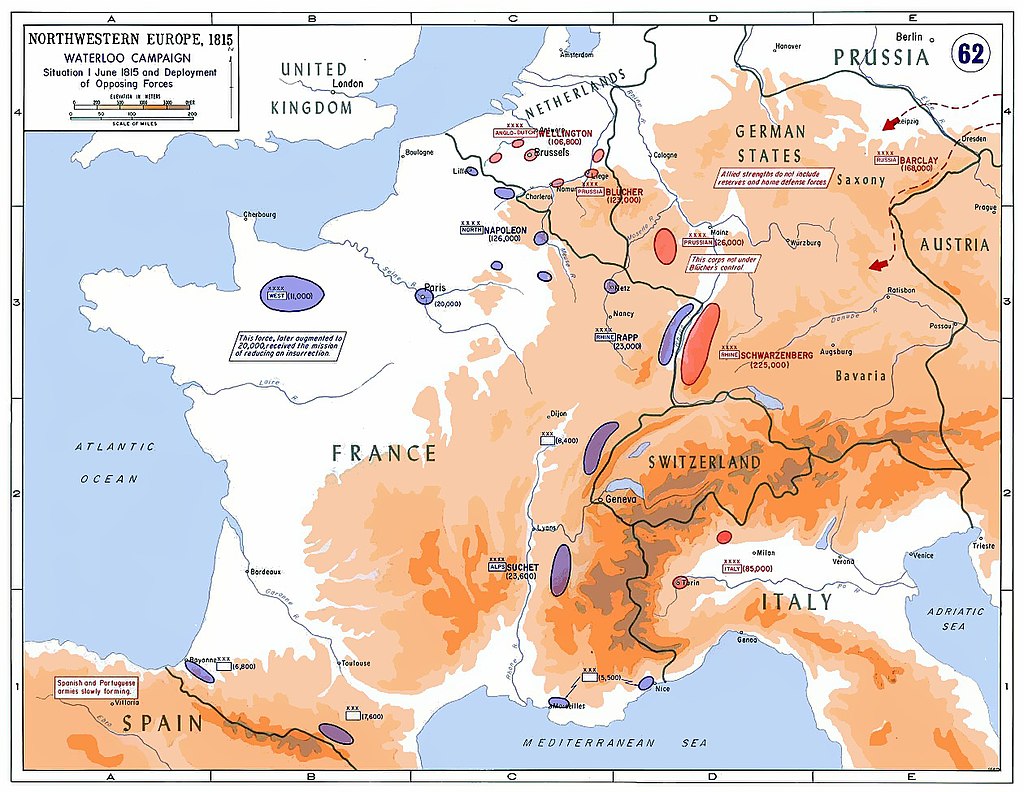

But Wellington didn’t stay there long. A month after his arrival Napoleon returned, and a month after that he was in Brussels, taking up command of an Anglo-Dutch army being assembled to fight Napoleon.

Our next group of letters come from this period, April 1815, when Wellington is preparing for war in Brussels, while 40 miles away Louis and what was left of his court were in exile in Ghent. The situation at this point was extremely fluid, and Wellington knew no more than anyone else about how things would end up. We pick up with Wellington recounting a meeting he had with the Comte d’Artois, in which the count alleged that his cousin the Duc d’Orléans was involved in a conspiracy to usurp the throne.

The United States Military Academy Department of History, “Strategic Situation of Western Europe, 1815.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Brussels, April 11, 1815. Wellington to Castlereagh9

My dear lord,

I have since seen Monsieur… and he told me that the truth was that the Jacobin party in France, and a great proportion of the army, looked to place the Duc d’Orléans on the throne. Monsieur protested repeatedly that he entertained no suspicions of the Duc d’Orléans, but that he was certain the subject had been more than once mentioned to the Duc, and that he could not help thinking that his conduct in absenting himself from [Ghent] at the present moment10 was very extraordinary.

I told him that I thought he ought to attribute his conduct to two motives: first, [Orléans’] desire to see his family; and, secondly, his feeling that he was unjustly suspected by the persons about the King, and his desire to keep out of the way on that account…

I entertain no doubt that the Duc d’Orléans is thought of. I heard of such a notion when I was at Paris; and you will observe that calling the Duc d’Orléans to the throne is the only acceptable middle ground between Buonaparte, the army, and the Jacobins on the one hand, and the King and violent émigrés on the other. I understand that the army showed a good disposition towards the Duc d’Orléans on his journey to and from Lyons and in the northern departments… Notwithstanding the respect and regard I feel for the King, and the sense which I entertain of the benefits which the world would derive from the continuance of his reign, I cannot help feeling that the conduct of his family and of his government during the late occurrences, whatever may have been his own conduct, must and will affect his own character, and has lowered them much in the public estimation.

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Brussels, April 24, 1815. Wellington to Castlereagh11

My dear lord,

I confess that every day’s experience convinces me there is but little chance of restoring the poor King… it remains to be seen who will be taken instead of him. You see, however, the degree of indifference of the Emperor of Russia, or rather prejudice, against the legitimate Bourbons…

I concur entirely with you as to our line. Our object should be if possible to restore the King, as the measure most likely to insure the tranquility of Europe for a short time; and although we cannot declare that to be our object, we should take care to avoid to do anything, and particularly to declare anything, which can tend to defeat it.

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Brussels, April 28, 1815. Wellington to his younger brother, Sir Henry Wellesley12

My dear Henry,

You will have heard that I arrived here on the 4th, and have taken the command of the army in this country, where I have been ever since making my arrangements and preparations for the campaign. We have here now, including Dutch, about 60,000, and we are in close communications with the Prussians on our left. They promise me more men from England; but it appears to me as if they were afraid there to touch the question of war, and they have most unaccountably delayed all their warlike preparations. The consequence is that the peace opinions are gaining ground fast; and I agree with you in thinking that if we only leave Buonaparte alone, we shall have him more powerful than ever in a short time.

I have not heard from Vienna for some days. When I left that place, and when I last heard, the opinions were unanimous for attacking Buonaparte and pushing the war vigorously; and the preparations are certainly immense… I think, however, that people are a little cool both at Vienna and in England in respect to the Bourbons… But if we are stout we shall save the King, whose government affords the only chance of peace…

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

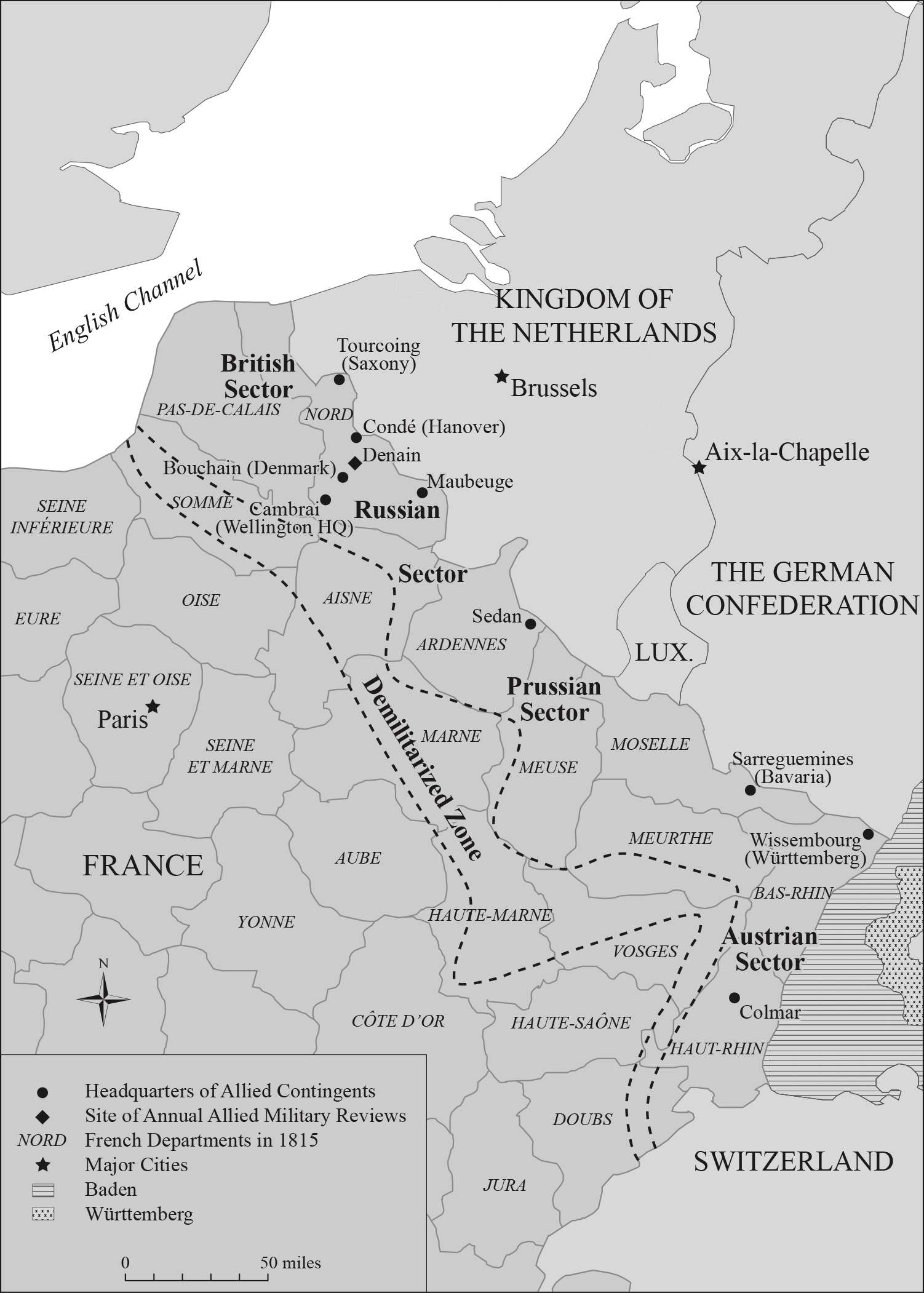

Part 3: Occupation

Below: Map of the occupation zones of the foreign “Occupation of Guarantee” in northeastern France from 1815 to 1818. Map © Christine Haynes, used with permission.

Wellington’s desire to restore Louis to the throne ended up being an important factor in making that happen, against the opposition of people like Tsar Alexander.13 After Wellington’s triumph at Waterloo, Louis infamously returned to the throne in Wellington’s “baggage train,” with the Duc d’Orléans and other potential candidates passed over.

This second occupation of France in as many years was, as I covered in Episode 5: The White Terror, much more brutal and lasting than the first. The subsequent peace negotiations established a new role for the Duke of Wellington: commander of the Allied occupation force that camped out in northern France for the next three years, to prop up Louis’s regime and ensure France paid its war indemnities.

This role — part military, part diplomatic, part administrative — left Wellington still at the heart of the action in France as Louis’s regime settled into its second go-round. But the most striking parts of Wellington’s correspondence from this time are the more mundane aspects of commanding an occupation force. For example, he ceaselessly has to write letters and orders telling British officers to stop trampling French farmers’ fields while hunting — instructions that his officers seem to have mostly disregarded, given how often he has to repeat the orders. Wellington also repeatedly orders his officers to carry their sidearms with them as a deterrent to their apparently too-frequent habit of getting into fist-fights with the French. The most dramatic and hilarious example of this was an incident in July 1816, when a British lieutenant in Boulogne got into a brawl with a French actor on the stage in front of the audience. This double shame — of provoking a public fight with an actor, and losing — sent Wellington into conniptions, and he repeatedly intervened to demand harsher punishments for the quick-tempered lieutenant.14

This is already going to be long enough for a supplemental, so I won’t bore you and amuse myself by reading out these fascinating but quotidian dispatches. Instead I’ll keep focusing on Wellington as a political commentator, one who was dismayed by both the apparent intransigence of the Comte d’Artois, and the seeming radicalism of the liberals who were gaining power under the ministry of Élie Decazes. As a result, Wellington was quite pessimistic about the future of the Bourbon regime at this time.

Mont St. Martin, Jan. 11, 1818. Wellington to J.C. Villiers15

Below: Peter Edward Stroehling, “Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, KG GCB (1769-1852), 1st Duke of Wellington,” 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

My dear Villiers,

Affairs are hurrying fast to a crisis. The government will carry no questions this Session excepting the Budget; and as they cannot obtain their natural support, the Court and the Royalists, they must endeavor to strengthen themselves by other means; and we shall see fresh contests in the country at the ensuing elections, in which the Jacobins and Royalists will be opposed to the government, to the advantage of the former. An additional number of Royalists will be removed from their employments, and the cause of the Royal family will lose still more ground in the country.

I entertain no doubt how this contest will end. The descendants of Louis XV will not reign in France; and I must say, and always will say, that this is the fault of Monsieur and his adherents.

I have been in France since the year 1814…and, notwithstanding my respect for Monsieur, I cannot but be of the opinion which I have just now communicated to you. To this I will add that it is not my opinion only, but it is that of every well-thinking man who has had the same opportunities of obtaining a knowledge that I have.

I wish Monsieur would read the histories of our Restoration and subsequent Revolution, or that he would recollect what passed under his own view, probably at his own instigation, in the [French] Revolution. The conduct of the Royalists in joining with the Jacobins against the Moderate party certainly led to the King’s death…

It is really time that this should end. The Sovereigns of Europe will meet in the autumn of this year, to consider the state of France and of the federal system for Europe to adopt in reference to that state. We are bound to the dynasty of Monsieur in no way;… and this may be depended upon, that if he and his party… go on as they have done, the Powers of Europe will unite in a system to avert from themselves revolutionary changes, leaving France to herself, and Monsieur to find his own way through them. I know, and Monsieur will then see clearly, that he has not a chance of reigning; and he will then repent, but too late, the false direction which he has given to his party during the reign of his brother.

Believe me, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, June 11, 1818. Wellington to the Earl of Clancarty, British ambassador to the Netherlands16

My dear Clancarty,

External appearances would induce me to believe that matters were going on better here. The [government] funds are rising in value, there is an astonishing avidity to participate in the profits of the new loans, and the whole country is in a state of tranquility. But knowing this people as I do, I cannot place implicit reliance on these symptoms.

I believe that the existing government, or at least some of them, mean well; but they are miserably fond of a low, vulgar popularity, which after all, as usual, they have not obtained. But in order to obtain it they court and reward their enemies, that is to say, the enemies of the present dynasty, and oppress its friends; and I am not astonished at the uneasiness felt and expressed by Monsieur and others upon seeing in all the military employments and all places of trust in all branches of the government the enemies of his house, and those who have already betrayed the King and his family…

Ever, my dear Clancarty, yours most sincerely,

WELLINGTON

Part 4: Spain

Below: Richard Evans, “George Canning,” circa 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

After the occupation ended in late 1818, as I covered in Episode 14, Wellington went back home. He next reenters our narrative after 1820, when liberal revolutions in Spain, Naples, and other places spurred a backlash from Europe’s conservative great powers. In the years that followed, Austria would crush revolutions in Italy, and in 1823 France would do the same south of the Pyrenees. I covered all that in Episode 18: The Road to Trocadero.

After the occupation ended in late 1818, as I covered in Episode 14, Wellington went back home. He next reenters our narrative after 1820, when liberal revolutions in Spain, Naples, and other places spurred a backlash from Europe’s conservative great powers. In the years that followed, Austria would crush revolutions in Italy, and in 1823 France would do the same south of the Pyrenees. I covered all that in Episode 18: The Road to Trocadero.

Wellington was caught up in all of this, first as Britain’s representative at the Congress of Verona. That was the summit where Austria, Russia and Prussia pushed for a collective response to these revolutions, and Britain, in the person of Wellington, resisted them due to a mixture of ideology and national interest. In particular, Wellington tried gamely and unsuccessfully to prevent France from invading Spain — a topic on which he was something of an expert!

Most of Wellington’s letters dealing with France in this period are addressed to George Canning, the British diplomat who succeeded Castlereagh as foreign secretary.

Paris, Sept. 21, 1822. Wellington to Canning17

Sir,

I had a long discussion with M. de Villèle yesterday on the relations of this government with Spain… It appears that for a considerable time past… the French government have been collecting troops in the southern departments of France, and that they have now an army of 100,000 men of all arms, fully equipped for the field, so posted as that they can be collected for service in a very short time…

There are two opinions in the [French] Cabinet regarding the mode of making use of this force. Some are of the opinion that they ought to proceed at once to attack the Spaniards… The object of this last would be to rescue the person of the King… It was not difficult to convince M. de Villèle — as, indeed, it was his own opinion — that this plan was attended by all the difficulties and risks of any invasion of Spain under any circumstances, and that it most probably would produce no result whatever… It was, besides, to be apprehended that his Catholic Majesty would inspire no confidence, and would be joined by few, if by any, of the leading characters of the country; and that the cause would become more unpopular in consequence of his having been assisted by a foreign, and, above all, a French army.

M. de Villèle admitted the truth of these, and other observations which I made upon this plan, to which he said his own opinion was opposed, although he thought that the other alternative — that of waiting to see the result of what was going on — was not unattended by its inconveniences and risks… His object was to save the King from being deposed, and his Majesty and his Royal family from being murdered…

It appears that an apprehension is entertained by some of the moral contagious in France of the success of the Spanish revolution; though I think that when I pressed M. de Villèle upon this point he could not but admit that there was no great cause for such apprehension… He said, however, that every precaution had been taken to keep the troops separated as much as possible, and he stated his belief that the morale of the French army was very much improved, if it was not now entirely to be relied upon.

It is certain that there have not been wanting provocations to war on both sides. M. de Villèle assured me that this government had given no assistance or encouragement, whether in money or otherwise, to the Spanish insurgents; but from all that I have heard from other quarters, I should be inclined to believe the contrary…

I have now, I believe, made you acquainted with the result of a very long conversation with M. de Villèle, in which I must do him the justice to say that he displayed more ability, candor and fairness than I have ever observed in any French minister…

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Above: Jean-Sébastien Rouillard, “Joseph, comte de Villèle.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Verona, Oct. 29, 1822. Wellington to Canning18

Sir,

The Emperor of Russia… declared his intention of marching an army of 150,000 men through Germany, which he should post in Piedmont, in readiness to fall either upon France, if the Jacobin party in France should take advantage of the absence of the army, or of its possible disaster in Spain, to make any attempt upon the government; or upon Spain, if the French government should require its assistance.

… Prince Metternich and myself have each had more than one interview with the Emperor for the purpose of endeavoring to make him feel the danger to which he was about to expose the French government, and the inconveniences and difficulties in which he would involve himself by the adoption of a plan to which all Europe would be opposed.

I do not think that either of us have yet succeeded in making him feel all the consequences of his plans.

We have both tried to awaken the French ministers to a sense of its danger to them; and whether Monsieur de Montmorency is of the war party in the French ministry or not, I cannot tell; but it is certain that, to me at least, he expressed his sense of the advantages they should derive… from the presence of 150,000 Russians in Piedmont, and his admiration of the chivalrous spirit with which the Emperor of Russia was willing to step forward for their defense…

I hope that we shall get through these difficulties in a creditable manner, and that we may be able to maintain the peace of the world.

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, Dec. 10, 1822. Wellington to Canning19

Sir,

In the conversation which I had last night with Mons. de Villèle, he began by inquiring whether I was satisfied with what had taken place at Verona. I answered that it depended upon the question of peace or war; that if France could remain at peace, I had every reason to be satisfied; but if, as I apprehended, war was to be the consequence of what had been done at Verona, I could not be satisfied, nor could anybody…

I then informed Mons. de Villèle that I was authorized to tell him that his Majesty’s government were disposed and ready to adopt any measure which should be thought advisable to remove the difficulties existing between the French and Spanish governments…

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, Dec. 12, 1822. Wellington to Canning20

Sir,

I have seen the King this morning,and what he said to me was to the same purport as what Mons. de Villèle had said to me on the day I arrived here. I stated to his Majesty that I was authorized by my government to relieve the difficulties of his situation in relation to Spain. The King said, in very positive terms, that the best thing the British government could do would be to endeavor to prevail upon the Spaniards to modify their system in such a manner as to give the King of Spain some security for the safety of his person, and more authority, and to the system itself more stability. I stated, in reply… that I was very apprehensive that to give such counsel, our mediation with his Majesty being unasked, would be quite useless, would tend to irritate, and would deprive us of the means of being serviceable to preserve peace if a critical moment should occur.

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

Paris, Dec. 12, 1822. Wellington to Canning21

Sir,

Before I went to the King I heard that his Majesty was of late much altered, but I am much concerned to have to inform you that I found him more altered than I had expected. From his appearance I should suppose that he had had a paralytic attack. One of his Majesty’s eyes was more closed than the other, and his head, which was in a great degree sunk upon his chest, inclined to that side.

Although his Majesty was very attentive to what I said, and answered with his usual precision and intelligence, he appeared much less interested than usual in the subject of conversation, which embraced all that had passed at Verona, and he talked much less.

I am really very apprehensive that we shall soon lose him, notwithstanding that the several ministers declare that he is better than he has been.

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

London, March 11, 1823. Wellington to Frederick Lamb22

My dear Lamb,

I have always been of opinion that complete success or complete failure by France in this Spanish concern would be equally unfortunate for us. But I don’t think either very probable. Complete failure is out of the question. I give no credit to the stories of the revolt of the military… This Spanish bubble will burst, and there will be no military resistance at all… But this is not success in producing a political result. Much time, very large armies, and enormous expense will be required to conquer the country and establish a government in Spain… Monsieur de Villèle knows this as well as I do, and it is this knowledge which induces him to wish to get out of the concern if he can. I quite agree with you likewise regarding the interior of France. There is no danger of revolution excepting from the military, who are the real government. They could overthrow the Bourbons, but if they will serve the Bourbons the latter can overthrow the Constitution any day. Therefore this Constitution is not fit for France. I never thought it was so, and I know it will not last. As soon as the Bourbons are well seated in the saddle, that is to say, have real command of the army, they will kick the Constitution to the devil in reality, whatever may be the form which they will have.

I have, &c.,

WELLINGTON

As we covered in Episode 18, Wellington was right about the lack of resistance France would face in its military incursion into Spain. In the short term, he seems to have been wrong about the effort that would be needed to place King Ferdinand securely back on his throne — the French did not have to conquer the country bit by bit, and didn’t get caught in a quagmire. But to spoil future developments a little, Spain will not have an especially stable government in the years and decades following the French invasion of 1823.

There are so many other things I’d love to get into from these dispatches and letters, including a long saga surrounding a man firing a pistol at Wellington’s carriage in Paris in February 1818, and the Duke’s extended efforts to bring the French on board with Britain’s desire to suppress the Atlantic slave trade. But you’ve listened to me read 200-year-old letters for long enough.

What I found so fascinating about this whole exercise was getting extended, first-person accounts of many of the events I’ve covered already in the podcast. Wellington wasn’t always right in his observations and analyses, but he was often perceptive and seldom shy. I’ve excerpted some of these letters quite aggressively to take out many of the tangents and side-tracks, but even in this abridged format I think you get a sense of Wellington’s personality, and what events on the ground during the reign of Louis looked like to a certain type of observer, as they happened.

Before I go, I want to thank all the listeners who’ve sent me books from my wish list, including Roy Park for a fascinating book analyzing Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Now I’m going to stop recording and get back to writing the next regular episode of the show, Episode 27: Mission from God.

-

Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1867), 309, 319. Note that the disparity in formality in this particular instance may be connected to class. Canning was the son of an actress and failed businessman, while Wellington was an aristocrat and duke. Some of Wellington’s fellow aristocrats use less flowery language in addressing him, and Wellington uses more affectionate salutations like “My dear lord” but always addresses Canning as “Sir.” ↩

-

Major-General C. Macaulay to the Earl of Liverpool, in Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 9 (London: John Murray, 1864), 407. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Lord Viscount Castlereagh, in Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 9 (London: John Murray, 1864), 314-6. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Lord Viscount Castlereagh, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 9 , 346-7. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Lord Viscount Castlereagh, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 9 , 402-3. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to the Earl of Liverpool, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 9 , 422-3. ↩

-

“March next,” of course, is when the long-feared crisis actually unfolded with Napoleon’s return. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to the Earl of Liverpool, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 9 , 424-6. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Lord Viscount Castlereagh, in Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 10 (London: John Murray, 1864), 60-1. ↩

-

Instead of going to Ghent with the rest of Louis’s loyalists, Orléans fled to England, where he remained even after the king summoned him to Ghent. His decision to refuse the summons was partly a way to thumb his nose at Louis — the two of them never got along — but mostly political. Going to Ghent would have been a gesture of loyalty and support to Louis, and Orléans was signalling his disapproval of the king. It may have been savvy — liberal critics of Louis used having gone to Ghent in 1815 as an effective attack for years to come. Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions (London: Macmillan, 2007), 82. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Lord Viscount Castlereagh, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 10, 146-7. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Sir Henry Wellesley, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 10, 168-9. ↩

-

Price, The Perilous Crown, 83. ↩

-

The lieutenant’s name was Thomas Prior, and Wellington’s intervention eventually saw that he was court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to the loss of six months’ seniority. The court-martial initially acquitted Prior on the more serious charge, on the grounds that the actor hit first, but an irate Wellington demanded that the court reconsider. Charles James, A collection of the charges, opinions, and sentences of general Courts Martial […] (London: T. Egerton, 1820), 748-9. Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 11 (London: John Murray, 1864), 455-6, 502-4. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to J.C. Villiers, in Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 12 (London: John Murray, 1864), 212-4. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to the Earl of Clancarty, in Supplementary Despatches, vol. 12, 443-4. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to George Canning, in Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1867), 288-91. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to George Canning, in Despatches, vol. 1, 457-60. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to George Canning, in Despatches, vol. 1, 635-41. ↩

-

Probably. Unlike other letters, this one is described as a “Memorandum” with no recipient specified, but it is identical in form to other letters to Canning, and is preceded and succeeded by other letters to and from Canning. Despatches, vol. 1,, ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1867), 644-5. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to George Canning, in Despatches, vol. 1,, ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1867), 646. ↩

-

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to Frederick Lamb, in Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. Arthur Richard Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1867), 63-6. ↩