Supplemental 15: Art Greco

This is The Siècle, Supplemental 15: Art Greco.

Welcome back! Last time I covered the Greek War of Independence, from its beginnings in 1821 until its effective end at the Battle of Navarino in 1827.

But despite that being my longest episode to date, I didn’t get to cover one particular area that deserved attention: the impact of the Greek Revolt on French art.

That’s what I’m going to cover today, in a hopefully more manageable size! To keep things under control, I’m going to focus this episode around three particular works:

- A painting, Eugène Delacroix’s 1824 “Massacre At Chios”

- An opera, Gioachino Rossini’s 1826 “The Siege of Corinth”

- A novel, Alexandre Dumas’s 1844 “The Count of Monte Cristo”

I’ll be mentioning a few other artists and works here, but those three will be our guideposts. I’ll also be moving through this fairly briskly — this will be a surface-level discussion of the ways the Greek War of Independence impacted French fine arts, not a deep analysis of the bigger trends affecting French art at the time.

As always, you can visit thesiecle.com/supplemental15 to view a full transcript of this episode, along with footnotes and images — which might be particularly useful for this first section, as we discuss a painting.

The Massacre at Chios

The “Massacre at Chios” — spelled “Chios” in English, or “Scio” in French — may not be a painting you can immediately visualize in your head. It’s a famous painting, to be sure, with its own Wikipedia page, and it currently hangs in the Louvre. But it’s not as culturally ubiquitous as what may be Delacroix’s most famous work, “Liberty Leading the People,” which I guarantee you have seen somewhere.

If you haven’t seen “Massacre at Chios” at the Louvre, or aren’t looking at it online at thesiecle.com, it’s a gigantic oil painting, more than 13 feet tall and 11 feet wide, or 4.2 meters tall and 3.5 meters wide. The top third or so depicts a cloudy sky, while in the middle distance we see a burning village and scenes of violence. The eye is drawn to the action in the foreground, however, where a group of desperate Greek refugees are about to be cut down by Turkish soldiers. One Turkish soldier is in shadow in the center, wearing a turban and carrying a musket or rifle. Another, more prominent, is at center-right atop a rearing horse.

The refugees are a sad lot. Some beg for mercy, while others seem to lack the strength to move. One man slumps nearly naked with visible bloody wounds. Another, with an emaciated body underneath Greek-style robes, stares hauntingly into the distance. Most tragically, we see a toddler trying to suckle at the breast of his dead mother on the ground.

The historical background for the painting was a real April 1822 massacre on the Greek island of Chios, which I talked about in Episode 30. That was the island whose people remained neutral in the rebellion, but were drawn into the conflict by a raiding party of rebels from elsewhere. The Ottomans retaliated with both regular soldiers and bands of armed civilians, who fanned out across the island for weeks of indiscriminate violence. An estimated 25,000 Greeks were killed and perhaps 45,000 were sold off into slavery — more than half the island’s total pre-war population. Many others fled, leaving the island “a mass of corpse-strewn ruins.” Historian Mark Mazower notes that Delacroix’s painting is “not far from the truth.”1

Delacroix was not the first artist to depict the massacre at Chios. His friend Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps produced a lithograph in early 1823 depicting the same event, though with a very different composition. Decamps arranged his drawing fairly conventionally, with a single family in the center and symmetric scenes of violence in the background.2

Click here to view Decamp’s Massacre de Scio, which I am not legally allowed to reproduce

In contrast, some contemporary critics slammed Delacroix’s painting for lacking this conventional structure. The painter and critic Charles Paul Landon dismissed it as “a confused assemblage of figures, or rather of half-figures.” More revealingly, another critic said Delacroix’s chaotic composition suffered for not considering “that unity was of any importance for his painting.”3

The word “unity” might ring a bell for attentive listeners. Way back in Episode 16, Prof. Philippe Moisan described the revolution in the new Romantic movement in literature against the rules of Classical literature. And among the most prominent of those rules were the so-called “Classical unities” or “rule of three unities” — that a tragic play “needs to take place in one day, in one location, in one action.” Romantic authors like Victor Hugo controversially broke those rules, with plays like Hernani that took place over several months in multiple locations. Delacroix himself insisted he was not a Romantic, but that hasn’t stopped critics then and ever since associating him and “Massacre at Chios” in particular with Romanticism.4 His apparent violation of the old rules of painting, the unity of art, made this Philhellenic painting intensely controversial.

The word “unity” might ring a bell for attentive listeners. Way back in Episode 16, Prof. Philippe Moisan described the revolution in the new Romantic movement in literature against the rules of Classical literature. And among the most prominent of those rules were the so-called “Classical unities” or “rule of three unities” — that a tragic play “needs to take place in one day, in one location, in one action.” Romantic authors like Victor Hugo controversially broke those rules, with plays like Hernani that took place over several months in multiple locations. Delacroix himself insisted he was not a Romantic, but that hasn’t stopped critics then and ever since associating him and “Massacre at Chios” in particular with Romanticism.4 His apparent violation of the old rules of painting, the unity of art, made this Philhellenic painting intensely controversial.

Above: Artist unknown, Eugène Delacroix in 1822. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But while some critics recoiled at the jumbled composition of “Massacre at Chios,” others found it thrilling. The liberal writer Adolphe Thiers wrote of the Salon of 1824, where Delacroix’s painting was exhibited, that:

In our days, a revolution has broken out in painting as well as in all the arts, and already the [reactionaries] are lamenting and shouting against barbarity. They declare that painting is lost in France, that good traditions have been abandoned.5

Other liberals explicitly tied the artistic revolution of painters like Delacroix with the actual revolution taking place in Greece. Critic Auguste Jal wrote that the Greek of 1824 “dreams of independence and breaks his chains with which he hits his hated masters,” and that similarly, “the arts and letters will no longer be the slaves of a multitude of prejudices that have exerted a tyrannic reign over the world.”6

The overlap between politics and art wasn’t perfect. There were liberal Classicists and conservative Romantics. The scholar Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer notes that other than Thiers, most prominent liberal critics “disapproved of Delacroix’s Massacres on aesthetic grounds.”7

But these liberals tended to approve of the painting on political grounds, even if they didn’t like its look. Art was an important vehicle for critics to indirectly attack the French government’s ambivalent policy toward the Greek revolution in a period of newspaper censorship. One piece sarcastically responded to attacks on Philhellenic art for depicting sad or disturbing scenes:

Why should we be made sad by looking at such pictures? … Be careful not to stir the blissful indolence in which you spend your days; let us even forbid our newspapers to report all the massacres in Greece… Let there be human slaughter all over Europe, as long as you are not told about it or at least not see it[.] As long as the blood of the victims doesn’t stain the satin slippers of your wives, your dinner parties will be just as cheerful and friendly… 8

Of course, not every piece of Philhellenic art was Romantic or revolutionary; the cause of the Greeks drew many allies, especially after the conservative writer Chateaubriand joined their cause in 1824. Philhellenic paintings were “important for nearly a decade” and represented a fusion of artistic and cultural interests.9 For many people, the topic was appealing not so much for political reasons as because paintings of strange people in far-off lands looked “exotic, picturesque, and infinitely romantic.” Athanassoglou-Kallmyer catalogued more than 100 different French paintings with themes related to the Greek War of Independence.10

If you’d like to explore more, be sure to check out Athanassoglou-Kallmyer’s book French Images from the Greek War of Independence, which I’ve linked online at thesiecle.com/supplemental15.

The Siege of Corinth

Beyond art, Philhellenism became a dominant theme in French music during the 1820s — though this had to overcome some significant hurdles. Artists could instantly evoke Greece with visual signifiers like the outfit known as the “foustanela,” consisting of a sort of white kilt, knee-high socks and a white shirt.11 But Western Europe at the time had no conception of what “Greek” music sounded like, no motif that instantly transported the listener to Athens or Mesolonghi. In many cases, composers wishing to evoke Philhellenic themes fell back on using European military music to represent the Greek rebels. This, music historian Benjamin Walton notes, positioned the Greeks as “West to Turkey’s East” — since the Turks did have recognizable musical motifs. This included heavy use of cymbals, and the so-called alla turca style recognizable from the “rondo” movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 11.12

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “Rondo Alla Turca,” performed by Una Bourne, Sept. 16, 1925. Public domain via the Internet Archive.

There many Philhellenic songs in that era, just like there were abundant Philhellenic paintings. The simplest approach was just to rewrite famous songs like La Marseillaise with Philhellenic lyrics. Others went further, such as the “Chant grec” or “Greek Song” by Philarète Chasles and Hippolyte Chelard. A pseudonymous composer under the name “Nicoris,” possibly an exiled Greek, debuted a vocal trio called “Byron au camp des grecs,” or “Byron in the Greek camp,” which depicted a version of the Romantic poet’s arrival in Mesolonghi.13

Perhaps the most gifted composer to try to capture the Greek Revolution in music was Gioachino Rossini, the celebrated Italian creator of operas like The Barber of Seville. Rossini was a sensation in France, where his operas had been performed, but often in “bastardized or truncated versions” that led some of Rossini’s defenders to allege a conspiracy to marginalize the foreign Rossini.14 When he finally visited Paris for the first time in 1823, a “Rossini fever” erupted. Newspapers tracked his every move and every word. Famous names hosted Rossini for salons and parties. And he was the guest of honor at a banquet where Rossini and famous French composers exchanged lavish toasts.15

Perhaps the most gifted composer to try to capture the Greek Revolution in music was Gioachino Rossini, the celebrated Italian creator of operas like The Barber of Seville. Rossini was a sensation in France, where his operas had been performed, but often in “bastardized or truncated versions” that led some of Rossini’s defenders to allege a conspiracy to marginalize the foreign Rossini.14 When he finally visited Paris for the first time in 1823, a “Rossini fever” erupted. Newspapers tracked his every move and every word. Famous names hosted Rossini for salons and parties. And he was the guest of honor at a banquet where Rossini and famous French composers exchanged lavish toasts.15

Trying to capture some of this popularity, an official in King Louis XVIII’s household approached Rossini during his visit with a generous offer: a massive salary of 40,000 francs per year in return for Rossini bringing his talents to Paris.16 Rossini eventually accepted and moved to France in 1824. There his first significant work ended up being Il Viaggio a Reims, the comic opera in honor of Charles X’s coronation I discussed in Episode 28.

Above: Gioachino Rossini, by Constance Mayer, 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But this only satisfied part of Rossini’s deal with the French government. They wanted the grand maestro to glorify French fine arts with an opera in French.

For this, the Italian composer turned to self-plagiarism. In 1820, he had debuted an opera about a 15th Century war between the Venetians and the Ottoman Empire called “Maometto II.” It was an ambitious flop.17 Now, six years later, Rossini revised his score, and worked with Luigi Balocchi and Alexandre Soumet on a French libretto. The new opera kept the original’s Turkish villains but swapped out Venetians for Greeks.

It was a canny move. The combination of Paris’s obsession with Rossini with its obsession with the Greeks created a sensation when the newly renamed Le Siège de Corinthe, or The Siege of Corinth, debuted on October 9, 1826. It received “nightly standing ovations,” and rapturous crowds would follow Rossini home at the end of the night to show their appreciation.18

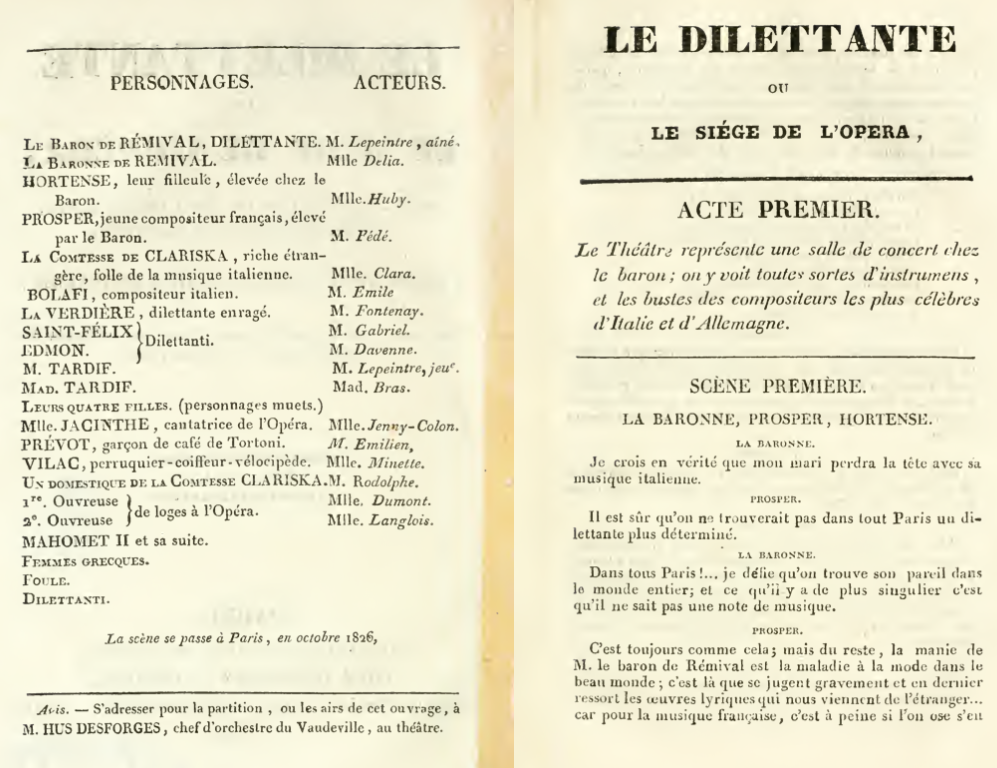

Perhaps the best sign of The Siege of Corinth’s popularity was that it provoked a parody: a play debuting less than a month after Corinth called The Dilettante, or The Siege of the Opera. (The word “dilettante” in the title signified at that time a sort of Restoration hipster, a true connoisseur of Italian opera who scorned “the blindly fashionable who go to the Opéra every night.”19)

The Dilettante wasn’t so much parodying Rossini’s work as it was the mania he provoked. The plot of The Dilettante concerned the titular music snob’s frantic attempts to find a way to get a ticket for The Siege of Corinth despite overwhelming popular demand, up to and including trying to sneak in disguised as musicians.20

First pages of the script for Le Dilettante, ou Le Siège de L’Opéra, a play by Emmanuel Théaulon, Théodore Anne and Jean-Baptiste Gondelier parodying Gioachino Rossini’s opera Le Siège de Corinth and the popular mania it provoked. Public domain via the Internet Archive.

We already saw last time how Rossini was openly sympathetic to the Greek cause, including supporting a pro-Greek benefit concert. The revised plot of The Siege of Corinth reflected that. The change in subject from Venetians to Greeks was in one sense cosmetic — the basic plot beats of the opera remained the same in both versions. But in another sense, it was deeply resonant. Both versions of the opera concerned a desparate and ultimately futile defense against a besieging Ottoman army. And while this plot fell flat when Maomaetto II debuted in 1820, when Le Siège de Corinthe debuted in 1826 the parallels were obvious: Corinth in 1459 was transparently Mesolonghi in 1826. That recent siege had ended in tragedy for the defenders, with many killed or captured while trying to escape. And — spoiler alert — The Siege of Corinth isn’t any less tragic.

Its plot, in brief, tells a love story set amid the Ottoman attack on Greek defenders of Corinth in 1459. The young Greek woman Pamyra is betrothed to a fellow Greek soldier, but is secretly in love with a man named Almanzor who she met in Athens. As the Turks advance, Pamyra recognizes that “Almanzor” was actually the Turkish leader Mahomet in disguise.21 As the Turkish soldiers storm the citadel of Corinth, the Greek defenders fight to the death instead of surrendering, and Pamyra stabs herself rather than let Mahomet carry her away.22

I’d love to play you samples from some of the opera’s arias, but all I could find that I’m legally allowed to play for you here is a 30-second excerpt from The Siege of Corinth’s overture. Here’s a taste of what you might have heard at the start of the show.

Gioachino Rossini, “Overture from the Siege of Corinth,” performed by the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Fernando Previtali conducting, 1968. Public domain via the Internet Archive.

Visit thesiecle.com/supplemental15 for an embedded live performance of the entire opera on YouTube.

The one area where Corinth’s plot was different from Maometto II is revealing, however. Rossini added a climactic scene dubbed the “Benediction of the Flags,” in which the chorus of Greek soldiers swears to fight to the death and receives a blessing. After this blessing, the priest23 declares a prophecy: that Greece faced defeat today, but would awaken again after five centuries. The metaphor isn’t subtle, and Philhellenic audiences received it rapturously. As Walton notes, “Almost no review, even the most critical, failed to praise the scene.”24

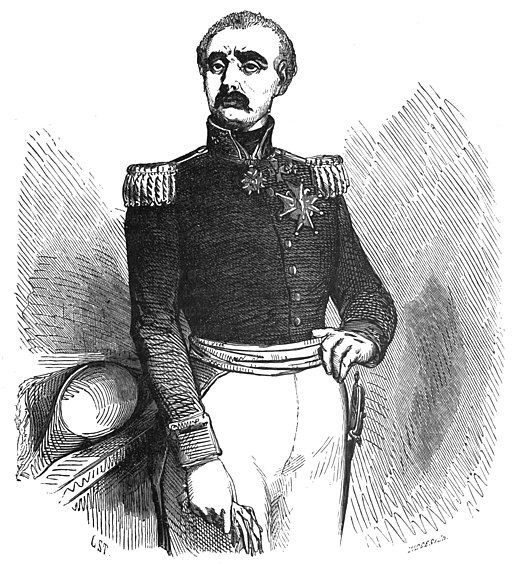

And there were critics, despite the opera’s smash success. This isn’t quite the same thing as the conflict of Classicists vs. Romantics that we saw with Delacroix’s painting — Rossini was sort of a transition figure between Classicism and Romanticism. But some of the beats are similar. Rossini’s works faced attacks from members of the cultural old guard as dangerous, populist innovations. Ironically for a composer remembered today for light, catchy melodies, in his day Rossini was attacked for the overwhelming noise of his compositions, assembled drums and brass that produced an almost physical sensation in the listener. One 1822 critique cited some people complaining “of experiencing too much pleasure and too many emotions at the same time” when listening to Rossini’s “insupportable uproar.” A review of The Siege of Corinth compared the sensation of listening to it to Napoleon’s Grande Armée on the march, and said it “came close to the extreme that music could achieve while remaining comprehensible.”25

Rossini, of course, had the last laugh — and not just musically. Almost exactly one year after the October 1826 premiere of The Siege of Corinth scandalized detractors with its open Philhellenism and thunderous orchestration, the combined fleets of France, Britain and Russia unleashed a still greater thunder in the Bay of Navarino. Corinth’s invented prophecy of a Greek revival after 500 years of slavery would come true after all, and the Philhellenic music of composers like Rossini had played no small part in bringing it about.

Any good biography of Rossini will discuss The Siege of Corinth and its reception, but if you’d like to learn more the most thorough account I’ve found is in Benjamin Walton’s book Rossini in Restoration Paris: The Sound of Modern Life. Its third chapter is all about Rossini and “musical philhellenism in Paris” and has formed the backbone of this section. I’ve included a link to this book at thesiecle.com/supplemental15.

The Count of Monte Cristo

We’re now going to jump ahead nearly two decades. Delacroix and Rossini created art about the Greek War of Independence while it was still going on. Alexandre Dumas, in contrast, completed his novel The Count of Monte Cristo in 1844, long after the war had ended. But events of the Greek Revolution were a crucial part of Monte Cristo’s plot, and I think it can serve as an illustrative example about how French people of that period thought about Greece, the Greek rebellion, and in general the concept of “the East.”

As a warning, I’m about to talk about some plot points from this novel. I’ll spoil as little as I can from the book’s climax, but some spoilers are unavoidable. If you’ve been putting off reading it for years and want to remain completely unspoiled, you might want to stop listening to this episode in a minute, and come back after you’ve read the book! But I hope this discussion will only enhance your appreciation of the book, rather than undermining it.

That out of the way, Monte Cristo is the story of young Edmond Dantès, an idealistic young man who is betrayed and imprisoned after being inadvertently caught up in Napoleon’s escape from Elba in 1815. After years in prison, he escapes, finds buried treasure, and returns to seek revenge in the guise of the exotic Count of Monte Cristo.

One of the characters that Dantès encounters is the Comte de Moncerf, who we’re told was originally a commoner who was conscripted during the Hundred Days. But right before the Battle of Waterloo, Moncerf joined a general in defecting from Napoleon to the Allies. Back in Episode 5, I talked about a certain General Bourmont who joined Napoleon but defected back during the Waterloo campaign, a possible inspiration for this incident.26 This timely betrayal put Moncerf on the rise in the Bourbon Restoration, and he was made a count after providing invaluable assistance during France’s 1823 invasion of Spain.27

After the Battle of Trocadero in 1823, Moncerf left for Greece to fight in the ongoing wars there, where he joined the service of one Ali Pasha as an “instructor-general.” Here’s how another character relates what happened next: “Ali Pasha was killed, as you know, but before he died he recompensed the services of [Moncerf] by leaving him a considerable sum, with which he returned to France.”28

Now, the Ali Pasha that this passage refers to was a real person: Ali Pasha of Jannina, an Albanian warlord who had a complex relationship with his Ottoman overlords. I basically skipped over him in Episode 30, but he actually played a vital role in the early years of the Greek rebellion.

Now, the Ali Pasha that this passage refers to was a real person: Ali Pasha of Jannina, an Albanian warlord who had a complex relationship with his Ottoman overlords. I basically skipped over him in Episode 30, but he actually played a vital role in the early years of the Greek rebellion.

Right: Raymond Monvoisin, Ali Pasha of Jannina, from “Ali Pasha and Vassiliki,” 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1821, as the Greeks were beginning their uprising, Ali Pasha was 80 years old and had been the ruler of his corner of the Balkans for decades. He governed some 2 million subjects at his peak with a “reputation for cruelty and cunning” — as well as a reputation for possessing fantastic treasure.29

So it shouldn’t be surprising that when the Greek uprising began in spring 1821 in the Peloponnese, the Ottomans initially saw it as a sideshow. The real threat from Sultan Mahmud II’s point of view was Ali Pasha, whose tensions with Constantinople had flared into open war the year before. Indeed, the Ottomans were convinced at first that Ali Pasha was behind the Greek revolt. In actuality, the plotters in the Filiki Eteria had been in touch with Ali Pasha as they formulated their conspiracy, but he had refused to commit himself fully. As historian Mark Mazower notes, rather than Ali Pasha being the father of the Greek uprising, a better word for their complicated relationship might be the code name that the Eteria gave Ali: “Father-in-Law.”30

The Ottoman belief that Ali Pasha was the real threat and the Greeks a sideshow turned out to be a very good thing for the Greeks, buying them crucial breathing room in the revolution’s first year. But it was a bad thing for Ali Pasha, who faced a more determined Ottoman assault than he hoped.

The Turks actually pulled soldiers out of the Peloponnese in late 1820 to help fight Ali Pasha, making the initial uprising much easier. This war with Ali was a see-saw affair, driven by the shifting allegiances of local warlords — Muslim and Christian alike. This was an old style of warfare, in which men fought for personal loyalty and personal reward rather than for abstract notions like nation or even religion. The local Greek chieftain Markos Botsaris, for example, served Ali Pasha, then turned against him to join the sultan, then changed sides again to rejoin Ali. He was far from unique, and Ali Pasha’s fortunes waxed and waned depending on the shifting allegiances of warlords like Botsaris.31

But the coming of the Greek uprising changed this system. Whether you want to categorize it as a nationalist revolution or a religious war, the new dynamics pressured people to choose a side and stick with it. One Albanian leader visited Mesolonghi in the fall of 1821 at the Greeks’ invitation, and was shocked to see razed mosques and Muslim bodies lying mutilated under trees. This was a “different kind of war,” and the slow realization spurred Muslim warlords to align themselves with the Ottomans instead of Ali Pasha, while Greek warlords came under similar pressure to join the rebellion for good.32

By the end of 1821, Ali Pasha had only 70 soldiers remaining and was trapped in his citadel. He began surrender negotiations with the Ottoman army, a tense affair that ended in betrayal and blood.

As Dumas tells the story in his novel, Moncerf had lied when he claimed to been granted part of Ali Pasha’s treasure as a reward for his faithful service. Instead, Moncerf had exploited Ali’s trust to betray him to the Ottomans, and was handsomely rewarded for his treachery while being lavished with undeserved fame as a Philhellene.33

As Dumas tells the story in his novel, Moncerf had lied when he claimed to been granted part of Ali Pasha’s treasure as a reward for his faithful service. Instead, Moncerf had exploited Ali’s trust to betray him to the Ottomans, and was handsomely rewarded for his treachery while being lavished with undeserved fame as a Philhellene.33

Right: The Comte de Moncerf, by an unknown illustrator, from the 1888 illustrated edition of The Count of Monte Cristo, Vol. 2. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Some of Dumas’ account is more-or-less accurate. He relates a dramatic scene in which Ali’s faithful servant Selim sits atop a pile of gunpowder, ready to blow up Ali Pasha, his family, and his treasure hoard if things went south.34 This is based on truth: Ali did pile up gunpowder barrels, receiving an Ottoman emissary while perched atop them, smoking his pipe. He was undone by treachery, though there’s no evidence any Frenchmen played any role. Instead, the Ottoman general had gradually talked Ali down with platitudes and peaceful negotiations, before finally sending in an armed delegation carrying Ali’s death warrant. The warlord was fatally killed in the ensuing shootout; his head was stuffed and sent to Sultan Mahmud’s court in Constantinople to be displayed.35

In the novel, we’re told that Ali Pasha’s favorite wife Vasiliki and her daughter Haydée were sold into slavery, and that Vasiliki died upon arrival in Constantinople. Haydée is an invented character, but Vassiliki Kontaxi was a real person, a Greek Christian who married Ali Pasha. She was taken to Constantinople, but unlike her fictional counterpart, she survived and returned to Greece in 1830. There she lived until her death from dysentery in 1834.36

Ali Pasha and his wife Vassiliki Kontaxi, also known as Kyra Vassiliki, by the school of Paul Emil Jacobs, 1844. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps the most notable discrepancy is that Dumas mangled the historical timeline. He has Moncerf sailing to Greece to work with Ali Pasha after the 1823 Battle of Trocadero. The historical Ali Pasha died in 1822.

Even though the timelines didn’t match up, Dumas was determined to shoehorn the man he dubbed as “one of the most singular [figures] in contemporary history” into his novel.37

But Ali Pasha’s supporting role in The Count of Monte Cristo also serves to highlight an important thread in Dumas’ novel: a fascination with the exotic East.

We’ve already seen how one of the reasons why Philhellenic art was so popular in the 1820s was a desire to see exotic scenes depicted. Years later, the lavish melodrama Dumas gives us with Ali Pasha’s betrayal is just one of many scenes where he luxuriates in orientalist tropes: hashish, slave princesses, poisons, even Sinbad the Sailor. Professor Silvia Marsans-Sakly has argued that Dumas used these tropes consciously, bringing up common ideas about Muslim decadence or cruelty and then drawing implicit contrasts with equally decadent or cruel Westerners. In the story of the fictionalized Ali Pasha, it is the Frenchman who is treacherous, not the noble Ali.38

The orientalist ideas in Monte Cristo draw on beliefs about the whole Ottoman world and beyond. But note how, writing in the 1840s, one of Dumas’s first instincts for an exotic eastern setting for one of his climactic revelations was the Greek War of Independence. Even long after the philhellenic fervor of the 1820s had ceased, the mystique of this far-off war retained a powerful hold on the reading public.

Thank you everyone for bearing with me as I tie up these few loose ends from the Greek Revolution. This has been a fascinating diversion from our main events back in France, but I hope you’ll agree that the impact we’ve seen on French culture and politics from this far-off war made the detour worth it.

We’re not done looking at Greece, nor at France’s relations with the Muslim world. But those will have to wait. Join me next time for Episode 31: The Election of 1827.

-

Mark Mazower, The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (New York: Penguin Press, 2021), 152. ↩

-

Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 1821-1830 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), 33-4. ↩

-

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 31. ↩

-

Stephanie Mora, “Delacroix’s Art Theory and His Definition of Classicism,” The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Spring 2000, Vol. 34, No. 1, 57 et passim. ↩

-

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 35. ↩

-

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 35. ↩

-

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 140n85. ↩

-

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 35-6. ↩

-

Paul Joannides, “Colin, Delacroix, Byron and the Greek War of Independence,” The Burlington Magazine, Aug., 1983, Vol. 125, No. 965, 495. ↩

-

Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 11, 152-5. ↩

-

Alexander Maxwell, Patriots Against Fashion: Clothing and Nationalism in Europe’s Age of Revolutions (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 170-1. Ironically, the foustanela appears to be of Albanian origin, but it became adopted by many Greeks and especially by foreign Philhellenes. ↩

-

Benjamin Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris: The Sound of Modern Life, Cambridge Studies in Opera (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 123-4, 150. ↩

-

Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 126-31. ↩

-

Gaia Servadio, Rossini (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), 114. Richard N. Coe, “Stendhal, Rossini and the ‘Conspiracy of Musicians’,” The Modern Language Review, Apr. 1959, Vol. 54, No. 2, 186-7. ↩

-

Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 41-2. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 329-30. ↩

-

The description comes from the author Stendhal, who identified with the term. Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 37. ↩

-

Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 108-9. ↩

-

Walton notes that critics at the time found this a coincidence that strained credulity, even by the standards of opera. Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 139. ↩

-

Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 139-40. ↩

-

In the opera, the officiant Hiéro is dubbed the “guardian of the catacombs” instead of a priest, but this was a labeling mandated by the censors. Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 140. ↩

-

Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 139-41. ↩

-

Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris, 14, 148-9. ↩

-

Though Bourmont defected the day before the Battle of Ligny, rather than the day after it, as Moncerf’s general did. ↩

-

Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo, translated by Robin Buss (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 261. ↩

-

Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo, 261-2. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 39, 41. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 37-8, 121. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 115-7. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 118-9. ↩

-

Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo, 871-2, 958-63. ↩

-

Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo, 854. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 120. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 130. ↩

-

Mazower, The Greek Revolution, 37. ↩

-

Silvia Marsans-Sakly, “Geographies of Vengeance: Orientalism in Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo,” The Journal of North African Studies 24:5, 2019, 1-18. ↩