Suppemental 20: What's a franc?

Title image: French five-franc coin, minted in 1814. Cropped from original published by Johnkrawczyk under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons.

This is The Siècle, Supplemental 20: What’s a franc?

I had hoped to be coming to you by now with Episode 40. Unfortunately, travel and illness have slowed my writing process, and I really want to get this next block of episodes right. So rather than rush Episode 40 out, I’m taking this opportunity to share some crucial background information I think everyone will find useful: a breakdown of the sometimes bewildering currency in use in Restoration France.

This stuff is hard for even experts to keep up on, for reasons I’ll get into in a bit. But hopefully this overview will help you better understand references to money in The Siècle — as well as in period fiction by authors like Balzac, Stendhal, Sand, Dumas and Hugo. Those authors often assume their readers understand their references to currency, which was a fair assumption at the time but definitely no longer holds.

My thanks again to Evergreen Podcasts, the network that hosts The Siècle, and to all the show’s supporters on Patreon. All patrons who contribute as little as $1 per month get an ad-free feed — and when I miss a monthly episode, I pause contributions so you don’t have to pay for my writer’s block. You can visit thesiecle.com/support to join them. Or visit thesiecle.com/supplemental20 for a full annotated transcript of this episode — including pictures of some of the coins we’re about to discuss.

So: what’s a franc? And more importantly, what was it worth?

The simplest answer is that the French franc was the official currency of France in the Restoration, and had been the French currency since being adopted by the First Republic in 1795.1 But to understand where the franc came from we’re going to have to take a very brief detour to Charlemagne, and before him to the Romans.

Below: A denier minted under Charlemagne, circa 793-812. Image by the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc., under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikiemdia Commons.

Among the reforms that the Frankish emperor Charlemagne imposed on his domains was a standardized system of currency based on three coins. The basis of this currency was a silver coin called the denarius, inspired by a Roman coin of the same name. Charlemagne’s denarius had about 1.7 grams of pure silver, or 0.06 ounces. Charlemagne also created a currency called the solidus, also based on a Roman coin, which was typically worth about 12 times a denarius. Finally, for large transactions, there was the pound, based on the value of a pound of pure silver. One pound of silver could make 240 denari, creating an exchange system where 1 pound (£) equalled 20 solidi equalled 240 denari.2

Among the reforms that the Frankish emperor Charlemagne imposed on his domains was a standardized system of currency based on three coins. The basis of this currency was a silver coin called the denarius, inspired by a Roman coin of the same name. Charlemagne’s denarius had about 1.7 grams of pure silver, or 0.06 ounces. Charlemagne also created a currency called the solidus, also based on a Roman coin, which was typically worth about 12 times a denarius. Finally, for large transactions, there was the pound, based on the value of a pound of pure silver. One pound of silver could make 240 denari, creating an exchange system where 1 pound (£) equalled 20 solidi equalled 240 denari.2

It’s worth noting that this was a system of currency, not a system of coins. In Charlemagne’s period and for some centuries thereafter, there was no such thing as a “pound” coin, and most of the time there was no solidus in circulation, either. The pound and solidus were a system of counting that gave people an easier way to express large quantities of denari.3

Now we have to talk etymology. A currency named the “pound” will be familiar to you, since the British still use the pound as the basis of their money. But the Latin name for a pound is “libra,” which gives us the English abbreviation “lb” for “pound,” the unit of weight. This also produced the names of pre-modern European currencies, including the Italian lira and the French livre.4

Similarly, the name “solidus” changed and endured. In English it became the “shilling,” which prior to England’s 1971 decimalization was worth 1/20 of a pound — exactly the ratio originally imposed by Charlemagne. In France, the solidus became the sou, which was also 1/20 of a livre.

The name denarius was adapted as the dinar by new Islamic countries as they conquered former Roman territory. In England, the denarius became the penny or pence, still worth 240 to the pound. In France, it was the denier.5

Now, this idealized system set up by Charlemagne would endure across the centuries as a standard of counting. But the actual coins minted by European countries in the medieval and early modern periods vary wildly. In France alone, there were coins in this period named the couronne, the écu, the salut, the mouton, the chaise, the florin, and, yes, the franc. There were also gold coins named after monarchs, such as the Henri d’or and Louis d’or, which translate as a “gold Henri” or a “gold Louis.”6

The value of these coins also fluctuated as kings and countries manipulated the amount of gold and silver in each one. While Charlemagne’s pound had somewhere between 330 and 410 grams of silver, depending on the region, by 1600 the English pound had 111.4 grams of silver, the French livre had 12.4 grams, and the lira had either 8.6 or 4.3, depending on whether you were using a Genoese coin or a Venetian one.7

That takes us closer to the period of our narrative. At the time of the French Revolution, a key French currency was the livre, which had 4.45 grams of silver. The revolutionary government would issue its infamous assignats, a paper currency originally backed by the value of confiscated land. The assignat system led to a period of hyperinflation that is beyond the scope of this podcast. When the dust cleared, a different revolutionary government returned France to metal currency in 1795. Instead of the old livre, a relic of the Old Regime, the new French currency was dubbed the franc. But it had 4.5 grams of silver, essentially identical to the old livre. Indeed, if you read novels from the time, characters switch interchangeably between referring to francs and livres — despite the name change, the two currencies were effectively identical.8

That takes us closer to the period of our narrative. At the time of the French Revolution, a key French currency was the livre, which had 4.45 grams of silver. The revolutionary government would issue its infamous assignats, a paper currency originally backed by the value of confiscated land. The assignat system led to a period of hyperinflation that is beyond the scope of this podcast. When the dust cleared, a different revolutionary government returned France to metal currency in 1795. Instead of the old livre, a relic of the Old Regime, the new French currency was dubbed the franc. But it had 4.5 grams of silver, essentially identical to the old livre. Indeed, if you read novels from the time, characters switch interchangeably between referring to francs and livres — despite the name change, the two currencies were effectively identical.8

Above: A silver écu (worth six livres) of Louis XVI, minted in 1783. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, by Jean-Michel Moullec, via Wikimedia Commons.

One difference the franc did have from the livre was how it was divided. The livre had been a descendant of Charlemagne’s pound-solidus-denarius system, and was primarily divided into 20 sous. The franc was a decimal currency, and was divided into 100 centimes. Again, though, the difference was smaller than it seemed. French people in the Restoration frequently referred to a 5-centime coin — one-twentieth of a franc — as a sou.9

There were a lot more denominations of French coin circulating at this time, but the most important one was a gold coin worth 20 francs, used for large purchases. What this coin was called varied based on the regime. Under the French Empire, it was called a napoléon d’or, a gold Napoleon — or just “a Napoleon.” Unsurprisingly, when the Bourbon Restoration replaced the French Empire, this coin was renamed to a louis d’or, a gold Louis. The face changed, but the value remained the same. (However, the coin continued to be called a “louis” even under the reign of Charles X.)1011

There were a lot more denominations of French coin circulating at this time, but the most important one was a gold coin worth 20 francs, used for large purchases. What this coin was called varied based on the regime. Under the French Empire, it was called a napoléon d’or, a gold Napoleon — or just “a Napoleon.” Unsurprisingly, when the Bourbon Restoration replaced the French Empire, this coin was renamed to a louis d’or, a gold Louis. The face changed, but the value remained the same. (However, the coin continued to be called a “louis” even under the reign of Charles X.)1011

Above: A gold napoléon coin depicting First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte, minted 1803. Image public domain via the National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

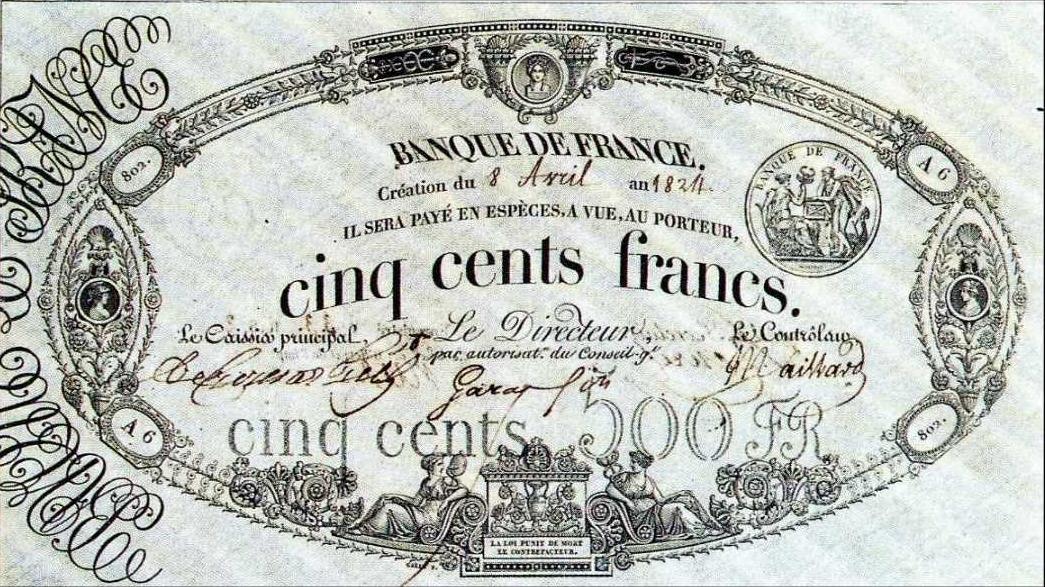

You might be wondering about paper money. The Bourbon Restoration did, in fact, print banknotes — but most people would never use them. That’s because the Bank of France printed banknotes in only two denominations: a 500-franc bill and a 1,000-franc bill. Used only for large transactions, these banknotes “circulated mainly in Paris.” As of January 1825, France had 150 million francs in banknotes, and 2.7 billion francs in metal currency.12

Above: French 500-franc banknote, printed 1824, via the Banque de France. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I want to close this section by sharing two important facts that make understanding 19th Century currency — francs or otherwise — much simpler.

One is that over the course of the 19th Century, there was very little inflation. Economist Thomas Piketty estimates that inflation averaged at most 0.2 to 0.3 percent per year in the 19th Century. That’s an order of magnitude less than the 2 to 3 percent annual inflation that was common in the 20th Century. So over this entire period, 1814 to 1914, a franc is a franc, whether we’re talking 1820 or 1880. Moreover, this also held true for other major currencies. Over pretty much the entire century, it was a good rule of thumb that one British pound was worth five U.S. dollars and 25 French francs.13

The second key rule of thumb to understanding money in the 19th Century is that there was a stable conversion between wealth and income. In general, safe investments like land or government bonds paid about 5% in annual interest.14 (Risky investments could earn you more, but also came with a much bigger chance of losing everything.) So if you read in Pride and Prejudice that Mr. Darcy earns £10,000 per year, you can assume his estate is worth 20 times that, or £200,000. And with the standard currency conversion rates I just mentioned, Darcy’s £10,000 is equivalent to $50,000 or 250,000 francs at the time.

Currency conversions

So now we know what French currency in this period is. But what is it worth?

Here I’ve got unfortunate news for you: there’s no good way to adjust 19th Century currency figures into 21st Century currency. Our economy is just so different than it was 200 years ago, with fundamental structural differences in the value of labor, commodities, manufactured goods, and more.

But there are several bad ways to adjust currency over 200 years. None of them will give you a good, complete picture. Taken together, though, these methods can give you a range of potential values, and perhaps some rough rules of thumb that can help you understand about how much various figures mean when they pop up on The Siècle or in novels.

As a warning to some of my listeners: I’m going to be making comparisons mostly in terms of contemporary U.S. dollars. I live in the United States, and stats say most of you do, too. For those of you in the European Union or Great Britain, though, you can — as of the time I’m writing this —just take any dollar figures I provide and adjust them down a little bit to get values in pounds or euros.

Perhaps the simplest way to adjust currency is to use the price of precious metals like gold and silver. The metals were valuable in the 1820s and remain valuable in the 2020s, and we have very good data going back centuries on the value of gold and silver.

So let’s take gold. The Restoration’s primary gold coin, the louis d’or, had 5.807 grams of pure gold in it. As I write this on April 20, 2024, the price of gold on the website BullionVault is $76.91 per gram. By that standard, a louis is worth $446.62, and a franc would be one-twentieth of that, or $22.33.15

So let’s take gold. The Restoration’s primary gold coin, the louis d’or, had 5.807 grams of pure gold in it. As I write this on April 20, 2024, the price of gold on the website BullionVault is $76.91 per gram. By that standard, a louis is worth $446.62, and a franc would be one-twentieth of that, or $22.33.15

Above: A louis d’or 20-franc gold coin minted under King Charles X in 1826. By cgb.fr, under the the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons.

But things aren’t so simple. (Get used to hearing that.) For one thing, that $76.91 price of gold per ounce as of April 20, 2024, is at or near a 20-year high, and up dramatically over just the past few months. The median price per ounce on BullionVault over the past 20 years is $45.40, which would put a louis d’or at $263.63 and a franc at $13.

Okay, so what about silver? We know that the franc had 4.5 grams of pure silver. Silver today — again per BullionVault — is worth a hair over $1 per gram, or about $4.55 for a 4.5-gram franc.16 That’s less than our gold prices. But that may say more about the changing relationship between gold and silver. For most of the 19th Century, there was a relatively fixed ratio in which gold was around 15 times more expensive than silver. Since then the ratio has fluctuated wildly, and the 2024 ratio is closer to 80:1.17

So that’s three different calculations based on precious metals that have given us a roughly 5:1 spread of possible conversions, from $4.55 to $22.33 for a franc in today’s money. I guess that’s… something? Anyway, let’s try a different approach.

Instead of gold or silver, we can use another timeless good to compare price changes: wheat. For his 2003 economic history, James MacDonald used a comparison to the price of wheat to estimate that one British pound in the 19th Century was worth about $90. That’s about $154 in 2024 dollars. At our standard 1-to-25 exchange rate, that puts a French franc as worth just over $6 in 2024 currency — much closer to the $4.55 value we got with the silver conversion than the much higher values from gold conversion.18

Wheat is just one part of the food picture, though. One report from a rural area of 19th Century France says that a family of four needed an income of 500 francs per year to avoid begging for food.19 We also know that it was typical for food to cost 50% or more of total expenditures by poor or working families.20 As it happens, in the present day governments have precise estimates of how much it costs for a family of four to buy a minimum amount of food. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s official “Thrifty Food Plan” estimates that a family of four in February 2024 would need $225.40 per week to buy food, or about $11,720 per year.21 If you assume our impoverished 19th Century peasants were spending two-thirds of their wages on food, then that gives you a figure of 1 franc equal to about $35 present-day dollars.

This has its own problems. For example, the USDA’s Thrifty Food Plan includes significant quantities of meat, dairy, fruit and vegetables.22 That would be a much more nutritious diet than that of a poor 19th Century French person, which would be mostly bread.23 A bread-centric diet today would certainly be cheaper, if less healthy, than the balanced diet recommended by USDA dietitians — which would in turn lower our perceived value of a 19th Century franc.

Underlying all of this is a long-term trend. The past two centuries have seen a very dramatic divergence between the value of two key things one can use money to purchase: goods and services. Over the years it has become much more efficient to produce industrial and agricultural goods, so prices — especially for industrial goods — have fallen in relative terms. In contrast, many service jobs have become only marginally more efficient. It still takes four musicians to perform a string quartet, even though all four musicians now have computers in their pockets! So the price of services has gone up in relative terms.24

So let’s look at some wages. While it’s hard to compare many jobs with 200 years ago — there were no computer programmers in Restoration France, nor are there many clog-makers active today — certain jobs are pretty timeless.

A carpenter in 1820 Paris might earn 3.25 francs per day. If this carpenter works an average of 6 days per week, that’s just over 1,000 francs per year — not a comfortable salary for Paris, but safely above the line of real poverty.25 On April 21, 2024, Indeed.com estimates that the average salary for a carpenter in the United States is $68,673 per year, including overtime pay. That’s about 68 times an 1820 carpenter — though the 2024 carpenter is earning his or her money over a considerably shorter work-week.26

You’ll note that example gives us a much bigger differentiation than our earlier figures — one franc is equal to $22 in gold, $6 in silver, $35 for food, or $68 for wages.

A more rigorous approach here comes from the Swedish professor of economics Rodney Edvinsson at historicalstatistics.org. Edvinsson’s calculations use Sweden’s economy as an intermediary and haven’t been updated since 2015, but they still give a good estimate. One franc circa 1820 could buy the equivalent of about $8 in Swedish goods in 2015, he calculates — but could pay for the same labor as $237 would buy in 2015.27

Finally, a lot of the time on the show when we talk about francs, we’re not talking at the individual level — we’re talking about governmental budgets. This can give us another way to compare. Now, we can’t simply compare budgets, because the entire structure of how governments raise and spend money is different in 2020 compared to 1820. But again we can get an estimate. Here we’re going to use a long-run data set published by the World Inequality Database that goes back 200 years. That includes estimates of “national income,” a statistic similar to gross domestic product, or GDP. And crucially, they adjust for purchasing power — the same calculations one might make for a present-day country whose economy is small, but where money goes further because goods are cheap.28 They give France’s 2022 national income at around $3.1 trillion in U.S. dollars, and its purchasing power-adjusted 1820 national income at around $80 billion in 2022 U.S. dollars. Divide those out and the ratio is 39 times — right in the middle of the estimates we’ve gotten from looking at goods and wages.29

Now you can hopefully see why I said there were no good ways to adjust Restoration currency to the 21st Century. But by looking at a few bad ways we can get glimpses at a fuller picture. As a very rough rule of thumb, if you encounter figures in French francs from the first half of the 19th Century, you can imagine 1 franc being equivalent to somewhere in the range of $25 to $100 — or slightly smaller figures if you’re working in euros or pounds. Just keep in mind these are all estimates, and the value of different things have changed at different rates over the centuries.

I could go on talking about 19th Century currency for an hour easily — for years, I’ve taken down notes every time a source mentions the cost of something in francs. But I’m going to make myself stop. This episode is intended to be a primer and reference, not a comprehensive overview. And besides, in just a few hours, I’m going to be hopping on a plane for my honeymoon. So the shorter I keep this, the better!

Thanks again to Evergreen Podcasts and all my Patreon supporters. And stay tuned next time as we tackle the initial response to Charles X’s Four Ordinances by some of the people most directly affected. Join me soon for Episode 40: The Journalists.

-

W.A. Shaw, The History of Currency, 1252 to 1894: Being an Account of the Gold and Silver Moneys and Monetary Standards of Europe and America, together with an Examination of the effects of Currency and Exchange Phenomena on Commercial and National Progress and Well-being, third edition (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896), 174. ↩

-

Angela Redish, Bimetalism: An Economic and Historical Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 5. James Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt: The Financial Roots of Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 478-9. ↩

-

Redish, Bimetalism, 5-6. ↩

-

Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt, 479. ↩

-

Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt, 479. ↩

-

Shaw, The History of Currency, 397-407. ↩

-

Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt, 479-480. ↩

-

Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt, 480. Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014), 104. Note that Piketty asserts that the pre-Revolution livre had 4.5 grams of silver, the same as the franc, while Macdonald asserts the livre had 4.45 grams of silver. ↩

-

Giovanni A. Galignani, Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide Through France (Paris, 1822), xxxviii. ↩

-

Galignani, Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide Through France, xxxviii. ↩

-

The other common slang term used for French coins in period literature is the écu. Like the livre and sou, the écu is an ancien régime coinage that survived as slang. In the 18th Century, the écu had been worth between 5 and 6 livres. In the 19th Century, “écu” was used as slang for a 5-franc coin. Shaw, The History of Currency, 406. Galignani, Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide Through France, xxxviii. Interestingly, the 18th Century version of the écu was part of a family of large silver coins minted as the silver supply expanded thanks to mines at Joachimsthal, Austria. That name became “thaler,” which was adapted into English as “dollar.” And unsurprisingly given their shared heritage, the 19th Century écu and dollar had similar values. Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt, 480-1. ↩

-

Roger Price, The Economic Modernization of France (Toronto: John Wiley & Sons, 1975), 34. ↩

-

Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 103-8. ↩

-

Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 53-4. ↩

-

“Gold price,” BullionVault, accessed April 20, 2024. ↩

-

“Silver price,” BullionVault, accessed April 20, 2024. ↩

-

Caroline Banton, “Trading the Gold-Silver Ratio,” Investopedia. May 31, 2023, accessed April 24, 2024. Longtermtrends, “Gold to Silver Ratio,” accessed April 24, 2024. ↩

-

Macdonald, A Free Nation Deep in Debt, 482. ↩

-

Alain Corbin, The Life of an Unknown: The Rediscovered World of a Clog Maker in Nineteenth-Century France, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 93. ↩

-

Mark Traugott, ed. The French Worker: Autobiographies from the Early Industrial Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 19. ↩

-

U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, “Official USDA Thrifty Food Plan, U.S. Average, February 2024,” accessed April 23, 2024. ↩

-

U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, “Thrifty Food Plan, 2021,” accessed April 23, 2024. ↩

-

Traugott, The French Worker, 19-20. ↩

-

Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 88. ↩

-

Guillaume de Bertier de Sauvigny, The Bourbon Restoration, translated by Lynn M. Case (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 250-1, 255. ↩

-

“Carpenter salary in the United States,” Indeed, accessed April 21, 2024. ↩

-

Rodney Edvinsson, “Historical Currency Converter (test version 1.0),” historicalstatistics.org, accessed April 22, 2024. ↩

-

Without this adjustment, France’s national income today is an eye-popping 191,000 times larger than 1820, which is functionally meaningless. ↩

-

World Inequality Database, accessed April 23, 2024. ↩