Episode 41: The People

I want you to imagine you’re a working-class Parisian in 1830. It’s a Monday, but you have the day off work — a rare holiday. So you’ve gone off with your friends to celebrate the way working-class Parisians often did: guzzling cheap booze in cafés and bars just outside the city limits, where alcohol wasn’t subject to Paris taxes.1

But it’s hard to relax on this particular afternoon — Monday, July 26, 1830 — because a burly man covered in ink-stains keeps yelling at you. At the whole café, really. He’s ranting about politics — something the King just did — and is trying to get everyone in the café to care about some new “ordinances.” But you’re a working man. You don’t have nearly enough money to vote. So you let the print-shop worker rant. You don’t care — it doesn’t affect you.

Your apathy will last less than 24 hours.

This is The Siècle, Episode 41: The People.

Welcome back, everyone. This is the second part of a series exploring the aftermath of the Four Ordinances issued by King Charles X of France in July, 1830 — from the perspective of the men and women experiencing these events on the ground. As a result, each episode will only show part of the picture — so if you haven’t listened to at least Episode 40, I highly recommend going and doing that now.

Last time, we followed Paris’s journalists, as men like Charles de Rémusat and Adolphe Thiers had to decide whether to risk arrest by publishing their newspapers in defiance of the Four Ordinances. Today, we’re moving a couple of steps down the social hierarchy of Restoration Paris, to look at the ways ordinary Parisians responded to all this political drama.

Before we proceed, I wanted to, as always, thank all of you for listening and spreading the word about this podcast. Thank you especially to my supporters on Patreon, including new backer Alex G. All Patreon supporters paying as little as $1 per month get access to an ad-free feed of the show.

Additionally, The Siècle is a proud member of the Evergreen Podcasts Network.

I also wanted to let you know of a cool event coming up next weekend! I’ll be presenting at Barricades, a fan-run convention about Les Misérables. It’s taking place online from July 12 to 14, 2024. If you’re listening to this episode live, you can go to barricadescon.com to register. I’ll be talking on Friday, July 12, about the police regime of the Bourbon Restoration, including the truth behind Jean Valjean’s infamous “yellow passport.” I’ll put a link in the show notes, or you can find a link in this episode’s transcript online at thesiecle.com/episode41.

Finally, before we dive in, I wanted to specifically credit the work of historian David Pinkney, without whom this episode couldn’t exist. Not only is Pinkney perhaps the preeminent recent historian of the events we’re covering now, he specifically conducted groundbreaking work to understand the role of ordinary people in them.

Alright, let’s pick things back up. As my story from the cold open made clear, most Parisians did not make a big deal about the Four Ordinances when they were published on Monday, July 26. This was true among rich people like the hesitant deputies we encountered last week, and it was even more true of poorer Parisians, who weren’t rich enough to have formal political rights.

The big exception were the workers for Paris’s many printing presses. There were perhaps 5,000 print-shop workers in Paris in July 1830, and they were absolutely impacted by the Four Ordinances. The First Ordinance threatened to shut down most of Paris’s newspapers — newspapers that these men earned a living printing. So many printers spent Monday trying to rile up their working-class comrades to join them in a sort of general strike. But as my story suggested, they initially had limited success.2 It’s not that Parisian workers didn’t care about politics — many of them did, despite being disenfranchised. But the struggle for print-shop workers wasn’t persuading their comrades that the Four Ordinances were bad. It was persuading them that the Ordinances were bad, and that they should take personal risks to oppose them right now. In many ways, that’s the same struggle we saw last time among Paris’s journalists.

Unrest

And just like among the journalists, many of Paris’s workers stayed on the sidelines as July 26 turned into July 27 — many, but not all. The printers were riled up, of course. And other Parisians took opportunities they got to show their displeasure. We already saw one such incident, when police showed up at the Palais-Royal to shut down a reading room on Monday evening. The reading room’s aristocratic owner defied the police, and got backup from the nearby crowd.

That same template played out Tuesday afternoon. You had a group of police setting out to enforce the Four Ordinances — in this case, trying to shut down the printing press of one of the dissident newspapers. You had a member of the elite taking a stand: the paper’s editor barred the door and took up a post in front of it, where he loudly accused the police of being a squad of burglars there to take his property. And you had ordinary people rallying to defend this rich elite. A growing crowd heckled the police trying to get into the barricaded newspaper, and when the police brought in locksmiths to force the door, the crowd bullied the locksmiths into refusing to work.3

In these instances we see a crowd that was reactive, responding to both aggressive policing and to incitements by people of a higher social class. But as Monday rolled into Tuesday, Paris also started to see incidents where proactive groups of Parisians started confrontations themselves. For example, after the confrontation in the Palais-Royal Monday night, the crowds didn’t disperse. Forced out of the Palais-Royal by police reinforcements, groups of angry Parisians began marching through the streets, smashing street lights. One group encountered a carriage belonging to Charles’ unpopular prime minister, Jules de Polignac — and greeted it by hurling rocks and cries of “Down with the ministers!” at it. Its windows smashed, the driver whipped the horses as the carriage raced through an angry mob to safety at the foreign ministry.4 Unrest had turned into a riot.

In these instances we see a crowd that was reactive, responding to both aggressive policing and to incitements by people of a higher social class. But as Monday rolled into Tuesday, Paris also started to see incidents where proactive groups of Parisians started confrontations themselves. For example, after the confrontation in the Palais-Royal Monday night, the crowds didn’t disperse. Forced out of the Palais-Royal by police reinforcements, groups of angry Parisians began marching through the streets, smashing street lights. One group encountered a carriage belonging to Charles’ unpopular prime minister, Jules de Polignac — and greeted it by hurling rocks and cries of “Down with the ministers!” at it. Its windows smashed, the driver whipped the horses as the carriage raced through an angry mob to safety at the foreign ministry.4 Unrest had turned into a riot.

Right: Jules de Polignac, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

That might seem like a big deal! But Polignac wasn’t too concerned. Neither was his passenger in his carriage, the naval minister d’Haussez, who was actually struck by a rock thrown by a rioter. The two men waited half an hour for the crowd to move on — then went back onto the streets on foot to inspect a nearby police garrison.5

By our standards, Restoration France was a fairly violent place. Street violence was “more talked about than done,” but it was common enough to be considered as a sort of omnipresent social reality, rather than always being worthy of note. Rival gangs of young men brawled in the street; so did members of competing workmen’s associations. These fights often involved not merely fists, but weapons, which circulated widely in Paris.6 Weekends, festivals and holidays not irregularly saw mass street violence, most especially during the collective outburst that was Carnival, “when a great deal of violence was tolerated, even expected.”7 Violence broke out in rural areas and urban areas alike, often street brawls between residents of neighboring communities.8 In Paris, fights broke out in theaters, including an 1817 brawl that broke out while the prime minister and police minister watched from their boxes. Unsatisfied with that fight, both sides wandered the streets of Paris the next day, wearing ribbons and flowers to declare their allegiances, and assaulting members of the other faction.9 Part of the job of a Paris police commissioner was to “distinguish between habitual, almost permissible, disorder, and a commotion that overstepped the boundaries.”10

At first glance, the disturbances of Monday evening seemed closer to the former — a mere riot, people letting off steam.11 And that meant it could be dealt with by the forces on hand.

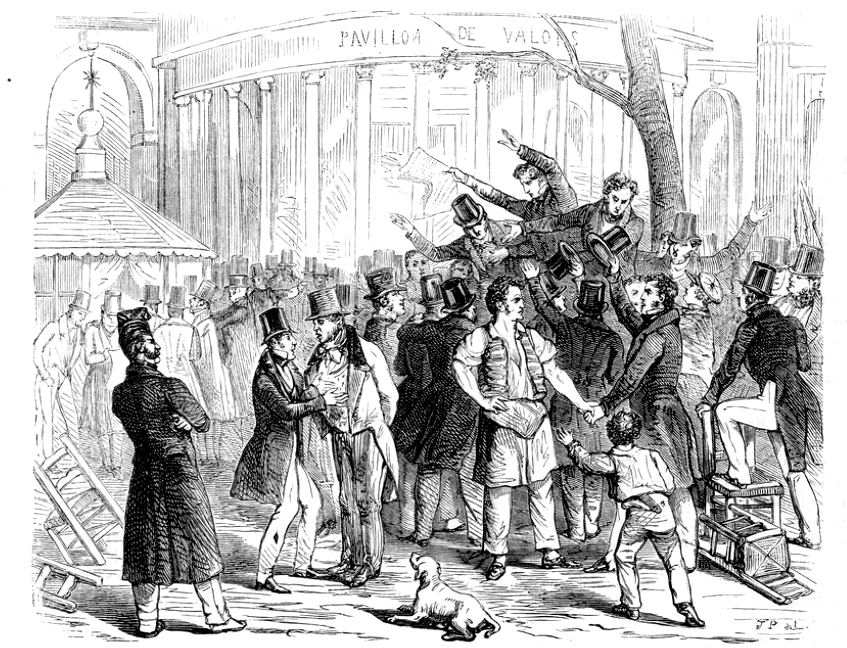

Jules Pelcoq, “Riot at the Palais-Royal,” in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque National de France.

The police

Paris in 1830 had several different agencies charged with keeping order and enforcing the laws. But there were fewer police than you might be thinking. Paris had 48 appointed police commissioners, one for each neighborhood of the city. There were also 21 “peace officers,” a separate organization whose jurisdiction overlapped with the police commissioners. Both police commissioners and peace officers were assisted on patrols by small squads of police inspectors, who numbered about 150 in total.12

If you’re doing the math, that’s a little over 200 men for a Paris that had somewhere over 750,000 residents.13 That might seem small! By contrast, the U.S. city of Seattle in 2022 had around 750,000 people with around 940 sworn officers.14

But these 200-plus men weren’t alone. Paris had a moderate military garrison, and the king had a heavily armed Royal Guard for his personal protection. Paris also had the gendarmes, a squad of 1,500 military policemen who were generally experienced former soldiers. Around 600 of these gendarmes were mounted, and the rest on foot. The gendarmes operated patrols throughout the city and assisted the civilian police officers with their missions. An English visitor in 1828 described the Paris gendarmes as “the finest, best appointed, and most soldier-like set of men I have ever seen” — but also noted their inadequacy:

[They] make the rounds in bodies of four or five and upwards — a consequence of which is that you may walk about the streets of Paris a whole night without meeting any of them. So that a man may be assassinated twenty times over, without obtaining the slightest assistance from these [sic] redoubtable gendarmerie.15

In general, the gendarmes had a reputation as “arrogant, aggressive, and brutal,” though many Parisians did not hesitate to seek out the gendarmes when in need.16

It was these 1,500 gendarmes who would be given the principal task of restoring order to Paris’s streets on Tuesday, July 27.

Heat

On Monday, only a handful of Parisians took any action at all in reaction to the Four Ordinances. And Tuesday started out looking like it might unfold the same way.

To be sure, the streets of central Paris were full of people. But that wasn’t unusual. Paris in 1830 was a city of predominantly apartments with no air conditioning in the middle of July. At 9 a.m. on July 27 it was 24.7º Celsius in Paris, or 76º Fahrenheit. By noon this had risen to 27º Celsius or 81º Fahrenheit. Rather than stay cooped up in stifling apartments, Parisians who didn’t have other places to be often congregated outdoors in central Paris’s many cafés, gardens, and public squares, and they did so on July 27, 1830.17 In fact, the crowds may have been smaller on Tuesday morning than they were on Monday morning, since Monday had been a holiday. A relieved Polignac told the Russian ambassador that morning that, “I was more fearful than I am now!”18

But Polignac didn’t know the full story. Mixed among the crowd were a host of people who were really mad about the Four Ordinances: journalists, newsies, and — importantly — 5,000 print-shop workers whose jobs had all just been taken away by the First Ordinance’s censorship. And unlike Monday, when some printers had tried and failed to rally opposition to the Ordinances, these dissidents on Tuesday had the fiery Protest of the Forty-Four, printed in defiant newspapers and on small handbills. This document, written by Adolphe Thiers, was a short and punchy denunciation of the Ordinances that explained why they were bad and called on Parisians to take action. It was read aloud at cafés and street corners on Tuesday by this group of journalists, printers, and newsies, who also added their own commentary. We don’t know exactly what any of this extra commentary said, but the net effect was both to raise people’s ire — and to help focus that anger on a particular set of political grievances.19

Into this volatile situation, around midday, came reports of raids by the Paris police on opposition newspapers. I already talked about those confrontations, which ended without violence. But news of these police actions transformed the crowds in central Paris. Suddenly chants of “Down with the ministers” started to be reported, as did graffiti attacking Charles X. Alarmed, many merchants started closing up their shops for protection. Meanwhile, bands of printers were reported actively assaulting gendarmes, such as a group around noon who “provoked a squad of mounted gendarmes… into charging up a narrow street where they were assaulted by stones and flower pots.” Another group was spotted ambushing a squad of cavalry with a flurry of hurled rocks.20

Seeing the mood turning, the Paris police at 1 p.m. sent in a squad of gendarmes to clear one major gathering place, the gardens of the Palais-Royal. The expelled Parisians relocated to a nearby square, where more shops closed their shutters. At 3 p.m., a squad of gendarmes was ordered to clear the square, and did so by charging on horseback with drawn swords. In response, protesters hurled rocks at the horsemen, but withdrew to the edges of the square. A regiment of Royal Guards then moved in, armed with muskets, to occupy the square and keep the crowd back.21

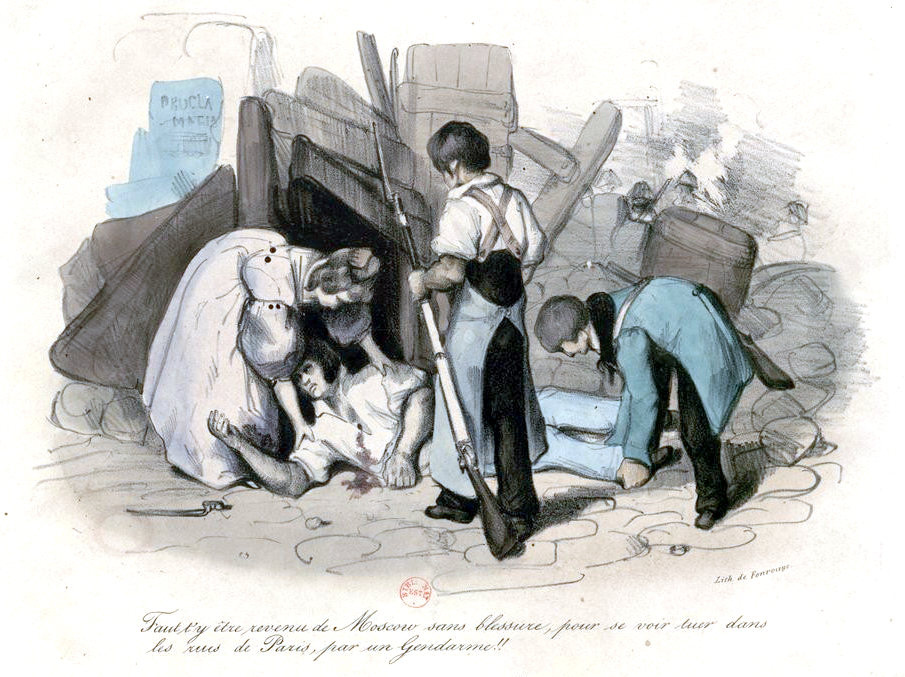

“You really had to return home from Moscow unharmed, only to get killed on the streets of Paris by a gendarme!” reads the caption of this 19th Century lithograph about the July 1830 street fighting in Paris. Art by Antoine Fonrouge, 1798-1855. Public domain via Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Death

What happened next was perhaps the pivotal turning point in this entire affair, and we know very little about who did what or why. What appears to be the case is that the protesters, pushed back to the edges of the square, taunted the Royal Guards and pelted them with rocks. Eventually, around 4 p.m., some of the soldiers snapped and opened fire on the crowd with their guns. These first shots may have been fired without orders, but now there were dead bodies on the ground, and everything changed.22

Whether or not his soldiers had fired without orders, the commander of the Royal Guard regiment now ordered a general advance. They moved into a nearby street and unleashed a mass volley of gunfire on the crowd. The fleeing protesters picked up the dead and began to carry them around Paris — held aloft and transformed into symbols. Historian Robert Tombs, having studied a series of successful and failed Parisian revolts, calls this “a true ritual of revolution” — “corpses being paraded round the streets in torchlight processions to arouse popular anger.” In 1830, these first casualties served to make it personal for many Parisians. This was no longer just about a dispute between two different groups of elites — this was about the people of Paris, murdered by their own government. At this point, the chants coming from the crowd began to change. Instead of “Down with the ministers,” it was now “Death to the ministers.”23

But if the people of Paris were now out for blood, they were facing opponents ready to deliver. After the first deaths Tuesday afternoon, the gendarmes and Royal Guards were swiftly reinforced by battalions of the French Army, thousands upon thousands of uniformed men marching out from their barracks to occupy strategic locations throughout the city. Many of these units had cannons as well as their muskets as they took up key positions in central Paris.24

A new phase of the conflict had arrived. Instead of a riot, with police facing off against mobs, you now had soldiers coming up against insurgents utilizing what would become the most iconic symbol of Parisian revolt: the barricade.

Barricades

Modern Paris is a city of grand, tree-lined boulevards, but those mostly didn’t exist in 1830. Instead, central Paris under Charles X was a warren of winding, narrow medieval streets. Shadowed by multi-story buildings, these streets sloped down toward the middle, central gutters that sometimes turned the streets into open-air sewers. There were no sidewalks and relatively few street lamps. Getting around these streets could be difficult in the best of times; the city’s array of carriages, hackney-cabs and more were observed to constantly “run into each other, cross paths, collide, pick up, drop off, and knock over day and night in the streets of this city.”25 So perhaps it’s not surprising that Parisians’ first instinct, as soldiers poured into the streets, was to block those streets.

We’ve actually encountered street barricades before on The Siècle, if only briefly. Back in Episode 31, I discussed some minor riots that followed the Election of 1827 — riots that climaxed in rioters building barricades to protect themselves from the police. Those barricades had been easily overcome, though, and overall they didn’t have much of a track record. Barricades had not been a major feature of the 1789 French Revolution, except for a minor appearance in 1795.26 But in July 1830, barricades sprouted up all over the city.

The dedicated revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui — who we’ll meet properly in the future — described what a typical barricade-raising looked like:

Five, ten, twenty, thirty, fifty men, having come together by chance, the majority unarmed, begin to overturn vehicles, lift and pile paving stones to bar the public roads, sometimes in the middle of streets, more often at their intersection.27

Construction of a barricade on July 28, 1830, after a drawing by Achille-Louis Martinet, 1897. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables has done as much as anything to cement the image of the Parisian barricade in the public consciousness. In it, he describes the construction of a barricade from later in the 1830s: Iron bars wrenched from a tavern’s grating, and empty barrels hauled up from its cellar; forty yards of cobblestones torn up from the street; passing vehicles commandeered and tipped on their sides, including a carriage full of passengers, and a cart full of barrels of lime; support beams torn from neighboring houses; and all of this cemented together with “two massive heaps of rubble.”28

Some barricades were small, little more than speed bumps to slow down soldiers. Others were massive constructions, several times the height of a man. As you can see, their constructions could be quite destructive to nearby buildings, homes and businesses — contributions that might be given willingly, or might be taken forcibly. The most universal casualty were paving stones, which were torn up in huge numbers. Blanqui estimated that a typical barricade would require 9,186 paving stones — or de-paving approximately 48 meters of street.29

Barricades could serve multiple purposes. In the early hours of an attempted uprising, they might simply be a “gesture of defiance,” that a given street or neighborhood was under the control of its residents. A few barricades were “miniature fortresses,” solidly build as fighting platforms to repel determined assaults. Many were intended more as obstacles: to slow troops down while insurgents attacked them from surrounding buildings. One Royal Guard in 1830 described his experience trying to clear a street:

When we meet a crowd they run as fast as their legs can carry them. Every door opens; in an instant everyone disappears; impossible to deal a single blow of a lance. Meanwhile gunshots, bricks, paving stones fall like hail from every window, without us even being able to see who is throwing them.30

Understanding the crowd

So how did we get to this point, where the passive “nation of shopkeepers” who had ignored the Four Ordinances on Monday afternoon were engaging in street fights with the French Army 24 hours later? As the immortal Ron Burgundy might say, that escalated quickly.

This is a complicated question with no one single answer. But a good place to begin is looking at who, exactly, the people in the Paris streets in late July, 1830 were.

That’s actually an easier question than you might expect. We have fairly detailed records of everyone killed in these events, and after the fact there were investigations that turned up more participants. And both the casualties and the investigations tell the same story: the rioters-turned-rebels of July 1830 were mostly adult men employed as skilled workers such as carpenters, masons, and, yes, printers. Only a few were women or children. Less than 20 percent were laborers or servants, and only around 5 percent worked white-collar jobs or owned businesses. Nearly three-fourths of the dead were skilled laborers. So any images you might have of a mob composed of beggars or street urchins are largely wrong. Likewise, this was largely not a bourgeois affair. As Pinkney dryly notes, “the middle and upper bourgeoisie were either immune to bullets or absent from the firing line.”31

Many of them were in the prime of their life. Of the dead and wounded with recorded ages, 54 percent were between 20 and 35 years old. Less than 5 percent were old enough to have any significant interaction with the 1789 Revolution. More than half were old enough to have served in Napoleon’s armies, and many had. Later investigations identified former officers or rank-and-file soldiers who took significant parts in the street fighting, often providing leadership to bands of workers without military experience. For example, one Alfred Minoret was an active-duty sergeant who was in Paris on leave. Despite his oaths to the crown, Minoret sided against the government when the fighting broke out, and he was noted for commanding a squad of workers, teaching them how to hold up under fire. Other observers also noted plenty of former soldiers, such as a doctor reporting that “two-thirds of those he treated” for injuries during the fighting “were veterans.”32

That still leaves open the question of why so many people chose the risky path of physical confrontation with first the police and then the army. There are some groups for whom this answer is easy, especially the printers, who were fighting for their livelihoods. But what drove locksmiths, cabinet-makers and tailors to man the barricades?

What the crowd believed

One answer we have to consider is economic motivations. As I covered in Episode 35, France was in the middle of a serious economic recession in 1830; work had been scarce and food expensive. And as I covered then, this misery had driven many people to participate in protests and riots over issues such as the price of bread. There is no doubt that some of the combatants took to the streets to protest their economic misery rather than the Four Ordinances. One army officer reported telling a crowd of Parisians to disperse, and being answered by a woman who said she “could not be calm when one lacked money to buy bread.” The officer gave her five francs, and she promptly began shouting, “Long live the King!” After the fact, the government compiled reports on 1,142 individuals who participated in the fighting; only seven mentioned economic reasons.33

Another possible motivation isn’t related to any beliefs at all. The question of what makes peaceful crowds turn violent has been subject to extensive research over the years, in topics ranging from political demonstrations to soccer riots. One current theory says the key factor isn’t primarily about the crowd at all, but rather the police. As scholars Clifford Stott and Steve Reicher summarize it, crowds ordinarily have lots of people with different beliefs and identities. But “to the extent that the police perceive the crowd as constituting a homogenous threat and then treat them homogeneously,” this can lead the crowd to adopt a collective identity where previously there was none. This new identity can mean that “resistance to the police is rendered acceptable” or even “seen as necessary self-defense.” And when people move from seeing themselves as individuals or members of small groups to members of “a group numbered in hundreds if not thousands,” this can make people feel more “empowered to act against [the police].” In other words, “police fears of [crowd violence]… may create the very conditions in which those fears are realized.”34

This theory isn’t universally accepted in the field of crowd studies35 but as a model it does seem to explain the developments of July 27 fairly well. Despite the presence of rabble-rousers reading the Protest of the Forty-Four all morning, the Tuesday crowds didn’t turn violent until reports of police raids started to spread after noon. That was followed by a series of tit-for-tat escalations, where the crowd and the authorities each became more violent in response to provocations from the other side.

A French government faced with disorder in Paris has lots of bad choices to make, Tombs found in his survey of Parisian revolts. Passivity could be “taken as proof of weakness.” But “excessive force… could inflame the situation.” Perhaps worst of all was to commit to force — but do so inadequately. “Too few troops… could lead to military debacle,” firing up the people without effectively suppressing them.36 That’s a pretty fair description of how Paris’s police and gendarmes interacted with the crowds on July 26 and 27 — able to win tactical victories, but never to fully secure the streets.

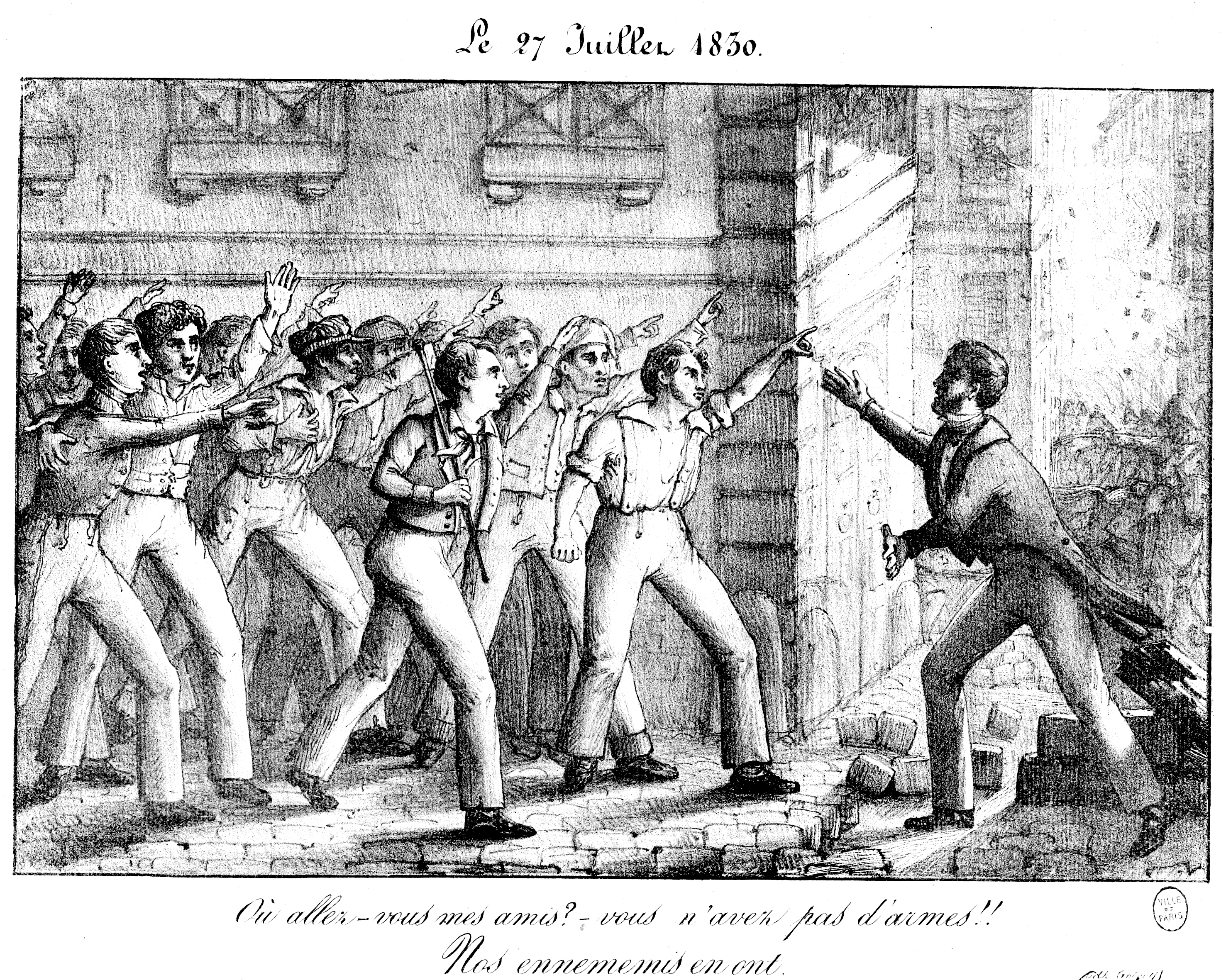

In this idealized scene from the first day of France’s July Revolution of 1830, a man asks a group of workers, “Where are you going, my friends? You don’t have any weapons?” They reply: “Our enemies have them.” Unknown artist, lithographer Gobert, circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Blouse and the Frock Coat

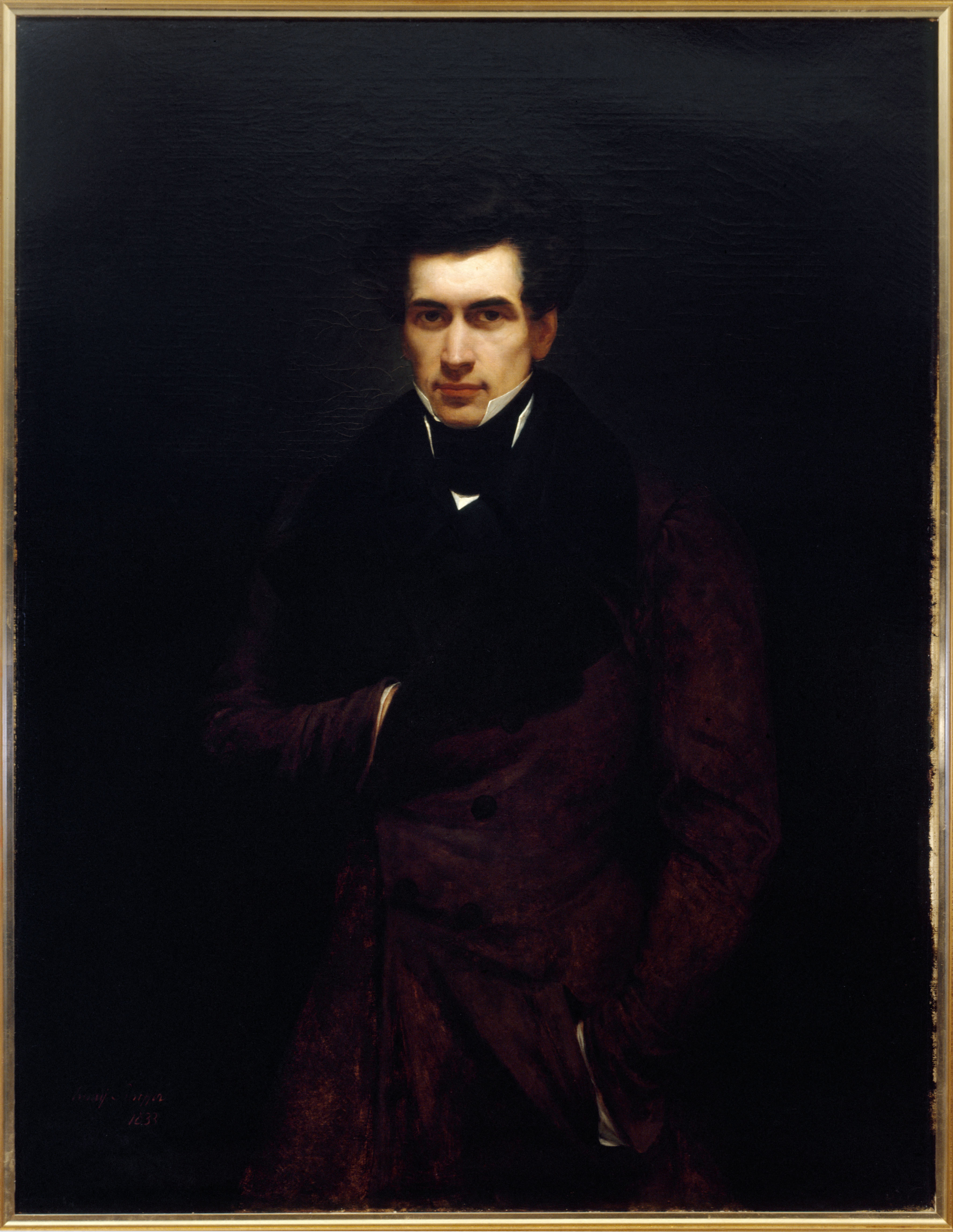

Below: Armand Carrel, by Ary Scheffer, 1833. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But even if these dynamics of police repression and crowd response explain a lot of what happened, they don’t explain all of it. It’s incontrovertible that many of the Parisians who resisted the authorities on July 27 were motivated at least in part by politics. They did not fight merely because they were poor or because the police had made them mad — they fought to resist Charles and Polignac, and to defend bourgeois liberal politicians from the Four Ordinances. Armand Carrel, a journalist who signed the Protest of the Forty-Four, relayed his experience with amazement:

But even if these dynamics of police repression and crowd response explain a lot of what happened, they don’t explain all of it. It’s incontrovertible that many of the Parisians who resisted the authorities on July 27 were motivated at least in part by politics. They did not fight merely because they were poor or because the police had made them mad — they fought to resist Charles and Polignac, and to defend bourgeois liberal politicians from the Four Ordinances. Armand Carrel, a journalist who signed the Protest of the Forty-Four, relayed his experience with amazement:

Everywhere in the streets men without coats, shirtsleeves rolled up, armed with muskets, and running to the defense of the barricades, said: “We want our Deputies; our Deputies know what we need, and the king doesn’t.”37

If you don’t trust Carrel, one of the editors of the National newspaper, then consider the account of someone who hated that the workers were supporting the deputies. Rather than deny it, the contemporary socialist historian Louis Blanc tried to explain it.

Below: Louis Blanc, artist unknown, from the frontispiece of Blanc’s 1850 book Organisation du Travail. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Blanc described the journalists and printers running from café to café with copies of the Protest on the morning of July 27, always closing with the liberal opposition rallying cry: “Long live the Charter!” This was a center-left cheer at the time, a defense of constitutional monarchy and a property-based suffrage. Radicals might have preferred other chants, such as “Long live the Republic,” or “Long live Napoleon II,” or even “Long live the nation” or “Long live liberty.” All of these were chanted at various times in late July 1830. But as Blanc related:

Blanc described the journalists and printers running from café to café with copies of the Protest on the morning of July 27, always closing with the liberal opposition rallying cry: “Long live the Charter!” This was a center-left cheer at the time, a defense of constitutional monarchy and a property-based suffrage. Radicals might have preferred other chants, such as “Long live the Republic,” or “Long live Napoleon II,” or even “Long live the nation” or “Long live liberty.” All of these were chanted at various times in late July 1830. But as Blanc related:

The men of the people, cast into the midst of a movement they could not comprehend, looked on with surprise… but gradually yielding to the contagion of the hour, they imitated the bourgeoisie, and running about with bewildered looks, they shouted as others did, [“Long live the Charter!”]38

The socialist Blanc saw these pro-Charter workers as dupes of the bourgeoisie, swept up in the moment, and doubtless some were. But many of these workers had read — or had read to them — liberal newspapers like Le Constitutionnel for years. These papers praised the Charter as a guarantee of French liberty, and attacked the Jesuits and the émigrés as threats to that freedom. When ultraroyalists had moved unpopular measures such as the “Émigré’s Billion,” it was elite liberal politicians like Jacques Laffitte or Casimir Périer who took the lead in fighting back. Unsurprisingly, historian Edgar Leon Newman has argued, in 1830 “the people seemed naturally to look to the substantial lawyers, bankers, and property owners of the constitutional monarchist party for leadership rather than to the impetuous and impecunious republican students” — much to the consternation of the republicans.39

But the fact that workers took to the barricades in defense of the Charter might say less than it seems. Historian William Sewell notes that while workers and elites both cheered for “liberty,” they didn’t necessarily define “liberty” in the same way.40

The Tricolor and the General

I want to close by pointing to two very different, but highly symbolic, actions that happened on July 27 to help spur Parisians into the streets and onto the barricades.

On the morning of July 27, someone — probably a band of law students — broke into the cathedral of Notre Dame, and unfurled a tricolor flag on the top of one of the church’s famous towers. The tricolor flag, under which the armies of both the Revolution and Napoleon had fought, had been banned under the Restoration, as I covered in Supplemental 8. Now here it was, flying over the heart of Paris. To make sure no one missed it, the intruders rang the great bells of Notre Dame.41

Symbols like flags are potent things. The tricolor did not fly above Notre Dame for very long, but it’s possible that amid ongoing street riots, the flag helped stir Parisian’s hearts — to remind them of a time when the people had toppled another Bourbon king. Whether or not the Notre Dame tricolor was the cause, observers noted a shift in the slogans shouted by the crowd after the tricolor was raised — in addition to the old chants of “Long live the Charter!” and “Down with Polignac!” were now ominous shouts of “Down with the Bourbons!” and even “Down with royalty!”42

Others point to a third development: the announcement that Charles had appointed a high-ranking general to suppress the unrest in Paris.43 People didn’t like Charles sending in the army, of course, but the particular general given this task was especially unpopular. Like many of the Parisians in the streets, this general had fought under Napoleon. But his too-hasty surrender to the foreign Allies during Napoleon’s defense of Paris in 1814 had made him — fairly or not — a popular scapegoat.

Next week, we’re going to follow this general as he brings this very complicated history to his unpleasant task of suppressing the uprising. Join me next time for Episode 42: Marmont.

-

André Jardin and André-Jean Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 1815-1848, translated by Elborg Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 366. ↩

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 260. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 94. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 91. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 92. ↩

-

Clive Emsley, “Policing the Streets of Early Nineteenth-Century Paris,” French History, vol. 1, issue 2 (October 1987), 275. ↩

-

Richard Cobb, The Police and the People: French Popular Protest, 1789-1820 (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), 91, 19. While Cobb was principally describing the ancien régime police, John Merriman notes that he “could as easily be discussing their successors during the first half of the following century.” John Merriman, Police Stories: Building the French State, 1815-1851 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 91. ↩

-

Clive Emsley, Gendarmes and the State in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 96. John Merriman, The Margins of City Life: Explorations on the French Urban Frontier, 1815-1851 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 208-9. ↩

-

Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814-1852 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 112. ↩

-

Cobb, The Police and the People, 18. ↩

-

“M. de Polignac believed that what he regarded as a mere outbreak of the mob would be very easily put down,” as contemporary historian Louis Blanc put it. Louis Blanc, The History of Ten Years: 1830-1840, vol. 1, translator unknown (London: Chapman and Hall, 1844), 110. ↩

-

Emsley, “Policing the Streets,” 258-61. ↩

-

Jardin and Tudesq, Restoration & Reaction, 372. ↩

-

Tammy Mutasa, “As cops leave and crime rate rises, Seattle police Chief Diaz eyes plan to turn the tide,” KOMO News, April 29, 2022. ↩

-

Emsley, “Policing the Streets,” 267-8. Emsley, Gendarmes, 89, 100. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 102. Philip Mansel, Pillars of the Monarchy: An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards, 1400-1984 (London: Quartet Books, 1984), 54. ↩

-

François Arago and Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, eds., Annales de chimie et de physique, vol. 44 (Paris: Crochard, 1830), 336. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 258. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 93. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 98, 261-2. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 99, 260. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 99-100. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 100. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 22. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 100. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 103. ↩

-

Masha Belenky, Engine of Modernity: The Omnibus and Urban Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 7-8. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 22. ↩

-

Jill Harsin, Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830-1848 (New York: Palgrave, 2002), 143. ↩

-

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, tr. Christine Donougher (Penguin Books, 2013), 986-7. ↩

-

Harsin, Barricades, 142. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 22. Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 243. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 22-3. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 252-6. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 257, 271. Sensier, Rapport de M. Sensier, ancien notaire, commissaire du 2e arrondissement, chargé de constater le nombre des victimes et les faits mémorables des glorieuses journées des 27, 28 et 29 juillet 1830 (Paris: Ambr. Firmin Didot, 1830), 34. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 263-4. ↩

-

Clifford Stott and Steve Reicher. “How Conflict Escalates: The Inter-Group Dynamics of Collective Football Crowd ‘Violence.’,” Sociology 32, no. 2 (1998), 359. ↩

-

Stott and Reicher, “How Conflict Escalates,” 355. ↩

-

Tombs, France 1814-1914, 22-3. ↩

-

Harsin, Barricades, 41. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years: 1830-1840, 100-1. ↩

-

Edgar Leon Newman, “The Blouse and the Frock Coat: The Alliance of the Common People of Paris with the Liberal Leadership and the Middle Class during the Last Years of the Bourbon Restoration,” The Journal of Modern History 46, no. 1 (March 1974), 35. ↩

-

William H. Sewell, Jr., Work & Revolution in France: The Language of Labor from the Old Regime to 1848 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 195. ↩

-

Mansel, Paris Between Empires, 240. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 267. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 267. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years: 1830-1840, 110. ↩