Episode 43: The Politicians

It’s important to understand that France’s liberal opposition had a plan.

These politicians had expected King Charles X and prime minister Jules de Polignac to launch a coup like the Four Ordinances for almost a year now. To be sure, they hadn’t expected it now — as shown by the fact that so many of them were escaping the heat on country estates, rather than gathered in Paris.1 But whenever the coup came, France’s opposition politicians were prepared to fight back.

Now, this plan very much did not involve the people of Paris rising up to battle the police and Army in the streets — despite accusations from regime officials like the naval minister, Baron d’Haussez, who alleged that the street rioters of July 1830 had been paid and organized by the opposition.2

No, the politicians didn’t want street violence if it wasn’t necessary. And they didn’t think it was necessary. The Polignac ministry was brittle and lacked popular support. If Polignac shut down the newspapers and rigged the elections, no matter — the liberal opposition could bring it to its knees with a campaign of civil disobedience. The plan had been formed in plain view, in easy defiance of the Polignac ministry’s clumsy attempts to suppress it. All they needed to do was activate it.

The plan was a tax strike. France’s liberal bourgeoisie would collectively refuse to pay taxes to an illegal government. Deprived of funds to pay soldiers, bureaucrats, and debt-holders, the illegal government would collapse. Constitutional government would be restored, all without death or property damage.3

It was a pretty good plan. But the people of Paris made their own plans after Charles launched his coup — plans that involved barricades and street combat against Marshal Marmont’s soldiers. So now it’s Tuesday, July 27, 1830, and France’s opposition politicians suddenly need a new plan — fast.

This is The Siècle, Episode 43: The Politicians.

Welcome back, everyone. Last time we left off with the military story of July 1830, as the tragic Marshal Marmont, called to defend a government he opposed, failed to suppress the people of Paris. This week, we’re rewinding to look at the political machinations that were happening — or, more often than not, not happening — behind the scenes.

First of all, I wanted to thank everyone who has helped spread the word about The Siècle, which is the only way a show like this grows. I especially want to thank the people who’ve just backed the show on Patreon: Lucas Arenson, Nick T., Joseph Stewart, Ronald Henry, Bryce Robinson, Julia, John, Brandon Stansbury, Meera, Sam Bee and Cecil Habermacher. They and all other patrons receive an ad-free feed of the show.

I also want to thank The Siècle’s podcast network, Evergreen Podcasts.

As a reminder, you can, as always, read a full annotated transcript of this episode at thesiecle.com/episode43. At thesiecle.com/support, you can find out how to back the show on Patreon, or how to buy the merch I now have available.

Now, without further ado, let’s get on with our narrative.

Meet the politicos

Below: Jules de Polignac, artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The liberal plan for a tax strike had been formed 10 months prior, in September 1829 — just a month after Polignac took office. It took the form of news reports about a so-called “Breton Association” that was organizing a tax strike. In fact, as I covered in Episode 34, no such group appears to have existed before the news reports — but after the idea got publicized, lots of real tax-strike groups popped up. Polignac’s government viewed this as so threatening that they tried to prosecute newspapers for reporting about it. Liberals, too, thought it a potent weapon. In July 1830, just three days before the Four Ordinances were published, the Duc de Broglie wrote a letter saying he was “quite certain that in case of a coup d’état the refusal to pay taxes would be prompt and universal, that this measure would be carried out without disorder, and that its success would be certain.”4 Opposition newspapers like Le National had turned in this direction in their initial publications after the Four Ordinances, with the National writing in a special Monday edition that “it is now up to the taxpayers to save the cause of the law.”5

The liberal plan for a tax strike had been formed 10 months prior, in September 1829 — just a month after Polignac took office. It took the form of news reports about a so-called “Breton Association” that was organizing a tax strike. In fact, as I covered in Episode 34, no such group appears to have existed before the news reports — but after the idea got publicized, lots of real tax-strike groups popped up. Polignac’s government viewed this as so threatening that they tried to prosecute newspapers for reporting about it. Liberals, too, thought it a potent weapon. In July 1830, just three days before the Four Ordinances were published, the Duc de Broglie wrote a letter saying he was “quite certain that in case of a coup d’état the refusal to pay taxes would be prompt and universal, that this measure would be carried out without disorder, and that its success would be certain.”4 Opposition newspapers like Le National had turned in this direction in their initial publications after the Four Ordinances, with the National writing in a special Monday edition that “it is now up to the taxpayers to save the cause of the law.”5

So with that in mind, and several other reasons I’ll get to shortly, the most important politicians in Paris on the first two days after the Four Ordinances — Monday July 26 and Tuesday July 27 — were not any of the liberal opposition leaders. Instead, the only politicians who were active in Paris on these first days were the members of King Charles X’s government. I discussed them all in Episode 39, but as a refresher for all of us, they were:

So with that in mind, and several other reasons I’ll get to shortly, the most important politicians in Paris on the first two days after the Four Ordinances — Monday July 26 and Tuesday July 27 — were not any of the liberal opposition leaders. Instead, the only politicians who were active in Paris on these first days were the members of King Charles X’s government. I discussed them all in Episode 39, but as a refresher for all of us, they were:

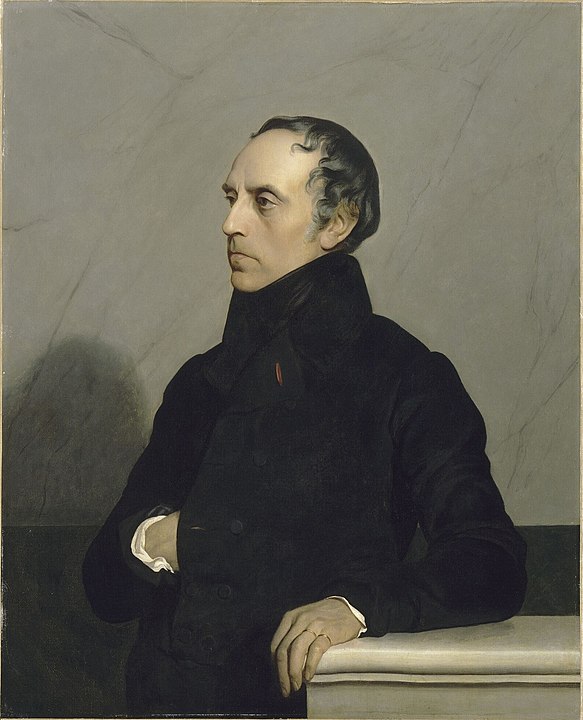

- Prime Minister Jules de Polignac, serving as Foreign Minister and acting War Minister.

- Minister of Justice Jean de Chantelauze

- Naval Minister Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez (Right: Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez, unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

- Interior Minister Pierre-Denis, Comte de Peyronnet

- Finance Minister Guillaume-Isidore, Baron de Montbel

- Education Minister Martial de Guernon-Ranville, and

- Minister of Public Works Guillaume, Baron Capelle

- An eighth member of the ministry was the War Minister, Marshal Louis-Auguste-Victor de Bourmont, but Bourmont was overseas in Algiers at this time, commanding the French army there

These seven men had known the Four Ordinances were coming and spent Monday implementing the Ordinances. But it cannot be said that they went about this with much vigor or speed. Rather than aggressively prosecuting a coup, Charles’s ministers “went serenely about daily business and making routine arrangements for application of the ordinances.” The Minister of the Interior, Peyronnet, sent out orders cancelling leave for all prefects and subprefects. The War Ministry, under Polignac as acting war minister, wrote to the commanding generals of France’s 21 military districts, notifying them of the Ordinances and instructing them to maintain discipline among their men — but not ordering any new soldiers to Paris. The Minister of Justice, Chantelauze, issued orders to the royal prosecutor for how violations of the Four Ordinances should be prosecuted.6 Polignac, as foreign minister, met with ambassadors to assure them that events were completely under control. “Set your mind to rest,” he told the worried Russian ambassador. “France is prepared to accept any of the King’s desires and to bless him for them.”7

These seven men had known the Four Ordinances were coming and spent Monday implementing the Ordinances. But it cannot be said that they went about this with much vigor or speed. Rather than aggressively prosecuting a coup, Charles’s ministers “went serenely about daily business and making routine arrangements for application of the ordinances.” The Minister of the Interior, Peyronnet, sent out orders cancelling leave for all prefects and subprefects. The War Ministry, under Polignac as acting war minister, wrote to the commanding generals of France’s 21 military districts, notifying them of the Ordinances and instructing them to maintain discipline among their men — but not ordering any new soldiers to Paris. The Minister of Justice, Chantelauze, issued orders to the royal prosecutor for how violations of the Four Ordinances should be prosecuted.6 Polignac, as foreign minister, met with ambassadors to assure them that events were completely under control. “Set your mind to rest,” he told the worried Russian ambassador. “France is prepared to accept any of the King’s desires and to bless him for them.”7

Above: Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo, Russian ambassador to France, 1814-1835, by Karl Bryullov, circa 1833-1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

What the opposition believed

Their opposition counterparts, the dastardly liberals whose evil schemes the Four Ordinances had been designed to thwart, managed to be even less vigorous on these first days. They, at least, had better reasons for their passivity, since they hadn’t expected the Ordinances this week. Some hotheads, including some of the young journalists I discussed in Episode 40 and a few more radical deputies, wanted an aggressive defiance of the Four Ordinances. But men like the businessman and deputy Casimir Périer advised caution.

Their opposition counterparts, the dastardly liberals whose evil schemes the Four Ordinances had been designed to thwart, managed to be even less vigorous on these first days. They, at least, had better reasons for their passivity, since they hadn’t expected the Ordinances this week. Some hotheads, including some of the young journalists I discussed in Episode 40 and a few more radical deputies, wanted an aggressive defiance of the Four Ordinances. But men like the businessman and deputy Casimir Périer advised caution.

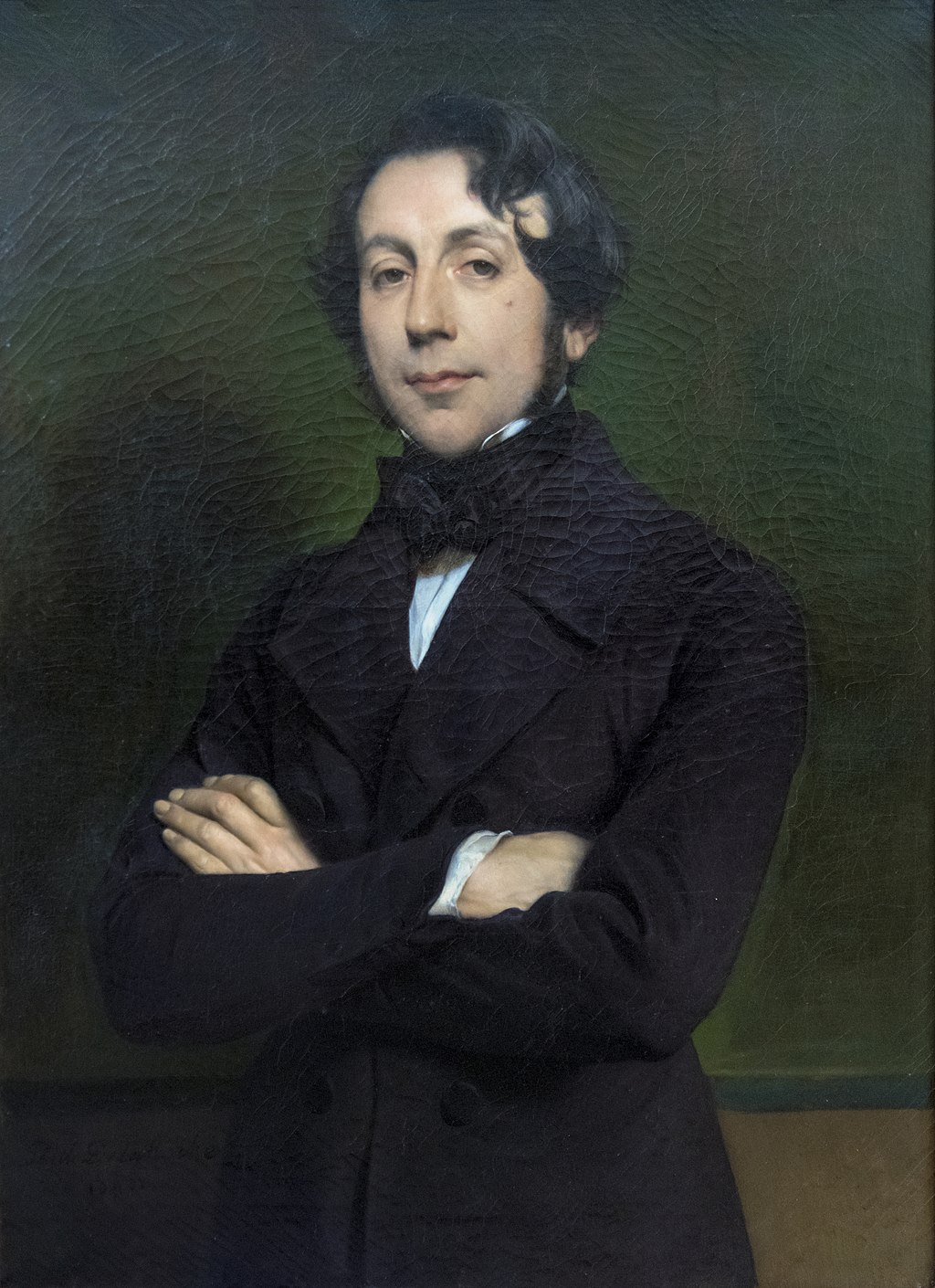

Left: Casimir Périer, by Louise Adélaïde Desnos, 1843. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Partly this was ideological — the French Revolution had occurred in living memory, and for many people the Reign of Terror was the logical consequence of pulling the common people into the streets. As I mentioned in Episode 29, liberals saw the 1789 French Revolution not as an unmitigated disaster as did the ultraroyalists, nor as a triumph of the people as did republicans, but as a mixed bag: a justified outpouring against tyranny that had then got out of hand. For many of the most prominent opposition politicians in July 1830, it was crucial that kings “not resist justified and necessary change,” but also that “‘popular’ passions must not be aroused.” As Adolphe Thiers eventually put it, “politics should be safe… from both the court and the street.”8 These were not men to back down in the face of Charles X, but neither were they men who would be quick to call the people to arms.

All that said, though, I think it’s just as important to focus in on two more tactical assumptions that were widely held among France’s political opposition in July 1830 — assumptions that would shape these politicians’s initial responses to the Four Ordinances until the fighting on the streets proved them wrong.

First, French liberals had seen over the past 15 years what happened when the opposition turned to force to resist an unjust government: utter disaster. Most notably, the Carbonari uprisings and other conspiracies of the early 1820s, which I covered in Episode 23, had not only been easily suppressed by the French Army, but had spurred a backlash that had helped cement ultraroyalist power for years. The 1820 assassination of the Duc de Berry led to the Law of the Double Vote that rigged elections against the liberals; the Carbonari uprisings in 1822 were followed by the 1824 elections in which the liberals were nearly driven out of the Chamber of Deputies altogether. Even those liberals who had stayed scrupulously within legal boundaries and rejected coups and rebellion were caught up in the backlash. Men like François Guizot and Benjamin Constant never joined the Carbonari conspiracies, but they condemned government prosecutions of conspirators — an awkward middle ground that failed to get charges dropped, but succeeded in associating the moderates with the illegality of their more radical comrades.9

Whether it was true that it was politically unwise for the liberal opposition to associate themselves with violent resistance is sort of besides the point. What matters is that many prominent opposition leaders believed this to be true in 1830, and not without good reason. Historian Robert Alexander puts this argument most strongly: “All the experience of the past fifteen years pointed to the dangers of armed insurgency — Allied intervention on the one hand, and, on the other, the way in which crowd violence had benefited political reaction in the 1820s.”10 Casimir Périer put this viewpoint most strongly when admonishing a would-be rebel on Tuesday afternoon: “You will destroy us in departing from legality,” he said. “You lose for us a superb position.”11

Second, and much more simply, almost everyone in Paris shared a crucial misconception in the immediate aftermath of the Four Ordinances: that Charles and Polignac would never have been so stupid as to launch this brazen coup without having the security forces in Paris to enforce it.12 Surely there were tens of thousands of soldiers in and near Paris, ready to massacre any attempt at revolution. If that were the case, caution was not just humane but a good tactic. When one radical urged Périer to take a sterner stance against the Four Ordinances, he emotionally refused: “Are you trying to make me responsible for the terrible events which seem to be in the making? This would be a catastrophe.”13

As we saw in Episode 42, of course, Jules de Polignac did not have overwhelming military force in Paris when he published the Four Ordinances. The people of Paris would be the first to realize this truth, as they took to the streets in increasing numbers. But France’s liberal politicians will slowly catch on, too.

Above: Detail from “Protest of the Deputies: July 27, 1830,” by Bichebois, 1830. Depicted are the deputies Louis Bernard, Joseph Mérilhou, Auguste de Schonen, Casimir Perier, Abel-François Villemain, Antoine Odier, Pierre Daunou, Nicolas Bavoux, Lefèvre, Vassal et de Alexandre de Laborde. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Initial hesitations

Trapped in their misconceptions and cautious tactics, men like Périer did not cover themselves in glory on July 26 or July 27. On midday Monday, a half-dozen deputies met at Périer’s house; they all agreed the Four Ordinances were illegal, but a majority held that “they lacked authority to protest them” until August 3 — the date the newly elected Chamber of Deputies was set to convene. In the evening, a slightly larger group of deputies met again, but “could agree on nothing except to meet again the next day.” Périer urged caution — 14 deputies couldn’t speak for anyone, but soon the rest of the recently elected Chamber would gather in Paris and could speak with their collective weight. The meeting broke up.14

Trapped in their misconceptions and cautious tactics, men like Périer did not cover themselves in glory on July 26 or July 27. On midday Monday, a half-dozen deputies met at Périer’s house; they all agreed the Four Ordinances were illegal, but a majority held that “they lacked authority to protest them” until August 3 — the date the newly elected Chamber of Deputies was set to convene. In the evening, a slightly larger group of deputies met again, but “could agree on nothing except to meet again the next day.” Périer urged caution — 14 deputies couldn’t speak for anyone, but soon the rest of the recently elected Chamber would gather in Paris and could speak with their collective weight. The meeting broke up.14

Above: Pierre-Denis de Peyronnet, unknown artist, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the same time, Polignac and his fellow ministers were having a somewhat more exciting night. In the evening, Polignac met with the Naval Minister Haussez, the Interior Minister Peyronnet, and the Finance Minister Montbel to discuss their next steps. After a while, the four men decided to walk over to the office of Chantelauze, the Justice Minister, who was “indisposed,” to bring him into the planning. But not much got done. Haussez, in his memoirs, writes that he “renewed my usual questions about what had been done to maintain order, and I received the ordinary answer.”15

At the same time, Polignac and his fellow ministers were having a somewhat more exciting night. In the evening, Polignac met with the Naval Minister Haussez, the Interior Minister Peyronnet, and the Finance Minister Montbel to discuss their next steps. After a while, the four men decided to walk over to the office of Chantelauze, the Justice Minister, who was “indisposed,” to bring him into the planning. But not much got done. Haussez, in his memoirs, writes that he “renewed my usual questions about what had been done to maintain order, and I received the ordinary answer.”15

Right: Jean Claude Balthasar Victor de Chantelauze, unknown artist, 1831. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As the evening went on, though, disorder began to increase in the streets of central Paris. Around 9 p.m., the ministers could hear the sounds of rioters nearby. Soon word came that there were rioters near the Finance Ministry, and Montbel left to see to the protection of his offices. Polignac and Haussez likewise left to check on the Foreign Ministry. But as I related in Episode 41, their carriage ran into a group of rioters, who recognized Polignac and began throwing rocks at it. One rock smashed the carriage’s window, and shards of glass cut Haussez. The carriage driver whipped the horses forward, and they managed to pull through the gates of the Finance Ministry and escape the crowd. Rioters remained outside for half an hour, throwing rocks at the building, before finally dispersing.16

With the streets once again calm, Polignac and Haussez ventured out again — this time on foot. They went to a nearby guardhouse, and found it scandalously relaxed given the recent attack on two government ministers. The officer in charge of the guard post had gone to bed! Polignac had him woken up and demanded sterner measures; the officer said he could raise another 150 men in the next two hours.17

Even Polignac recognized the inadequacy of this, and said he would alert the commander of the Royal Guard about the disturbances. In his memoirs, Haussez describes himself being shocked: “Hasn’t that already been done?” “You’re always worrying,” Polignac replied.18

Tuesday

Tuesday, July 27, began with the streets of Paris tense and increasingly crowded. By 9 a.m. Polignac had reported the crowds to the police, and — remembering the night before — asked for extra protection around ministry buildings. But he continued to be blithe and unconcerned. “I was more fearful than I am now,” he told the still-worrying Russian ambassador.19

The key events of the day didn’t involve the politicians. Four newspapers defied the First Ordinance to publish without authorization, printing the aggressive Protest of the Forty-Four, as I described in Episode 40. Crowds grew thicker in central Paris and began to clash with the inadequate police forces, as I covered in Episode 41. And as I covered in Episode 42, Marshal Marmont was belatedly informed he was in charge of the defense of Paris, and arrived to assume command not long before the shooting began.

“Many useless words”

While Paris was escalating toward revolution on Tuesday afternoon, the opposition deputies reconvened at Périer’s house, as they had agreed the night before. There were now 30 to 40 deputies, roughly 10 percent of the Chamber. More aggressive deputies such as Auguste Bérard wanted to issue a formal protest. Everyone there agreed in principle but many thought that publishing such a protest would be too risky. Everyone who signed a protest would be exposing themselves to legal consequences from a government that everyone still believed had ample security forces in Paris. “I am informed that troops are being assembled, that a confrontation is wanted and that it has been decided to strike a great blow,” Périer said Tuesday afternoon.20

While Paris was escalating toward revolution on Tuesday afternoon, the opposition deputies reconvened at Périer’s house, as they had agreed the night before. There were now 30 to 40 deputies, roughly 10 percent of the Chamber. More aggressive deputies such as Auguste Bérard wanted to issue a formal protest. Everyone there agreed in principle but many thought that publishing such a protest would be too risky. Everyone who signed a protest would be exposing themselves to legal consequences from a government that everyone still believed had ample security forces in Paris. “I am informed that troops are being assembled, that a confrontation is wanted and that it has been decided to strike a great blow,” Périer said Tuesday afternoon.20

Above: Portrait of Auguste-Simon-Louis Bérard, 1834, by David d’Angers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Below: François Guizot, circa 1837, by Jehan Georges Vibert after Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Meanwhile another rumor spread among the deputies that the government was planning to arrest and exile any deputies who defied the Four Ordinances. With all that, it seemed more “prudent” to wait and see. Instead of issuing a declaration like Bérard wanted, the deputies instead voted to have a committee led by the writer and deputy François Guizot draft a declaration that they could consider issuing tomorrow. With that settled, everyone agreed to come back at noon on Wednesday and then dispersed — some deputies slipping out the back door to avoid the police they feared were waiting to arrest them.21 There were no waiting police, but the deputies weren’t crazy to fear the law — warrants had already been issued for some of the dissident journalists, and had been prepared for some leading opposition politicians.22

Meanwhile another rumor spread among the deputies that the government was planning to arrest and exile any deputies who defied the Four Ordinances. With all that, it seemed more “prudent” to wait and see. Instead of issuing a declaration like Bérard wanted, the deputies instead voted to have a committee led by the writer and deputy François Guizot draft a declaration that they could consider issuing tomorrow. With that settled, everyone agreed to come back at noon on Wednesday and then dispersed — some deputies slipping out the back door to avoid the police they feared were waiting to arrest them.21 There were no waiting police, but the deputies weren’t crazy to fear the law — warrants had already been issued for some of the dissident journalists, and had been prepared for some leading opposition politicians.22

A final attempt from opposition leaders to do something came Tuesday night. This time there was a crowd of 40 to 50 men, including deputies as well as some journalists and liberal voters. Charles de Rémusat, who was there, wrote scathingly of its uselessness:

How many useless words are spoken in this kind of meeting cannot be imagined by a person who has not attended one. There are the earnest and the impetuous, who want to speak to satisfy their temperaments and to sooth themselves by declaiming at random. There are the boobs, who want to tell what they have seen or heard, believing it very important because it is all that they know. [And] there are the vain, who, preoccupied with themselves, insist on explaining their conduct…23

Right: Charles de Rémusat, 1843, by Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This meeting did take one minor action: a vote in favor of re-activating the electoral committees in each Paris district that had managed the recent elections. These committees, it was hoped, could coordinate opposition to the Four Ordinances — though at this point this was still envisioned to be peaceful opposition.24

At the very end of the night, Polignac and other ministers met and decided that they wanted to stop making decisions. They resolved that it was time to declare that Paris was in a “state of siege” — effectively, to put it under martial law with Marmont as dictator. A system of military tribunals would be set up with the power to issue summary justice. With that done, it would be Marmont’s job to resolve the crisis, not theirs, or so they thought.25

Wednesday

Wednesday, July 28, was the pivotal day of action. In Episode 42, I covered the fighting in the streets, as Marmont launched his assault columns against the barricades, but ultimately pulled back his soldiers, defeated. But Wednesday also saw developments from the politicians, who began to do more than simply hold endless meetings.

Sometime after 9 a.m., Polignac informed Marmont that Paris was now under his effective dictatorship. A few hours later, with the security situation deteriorating, the ministers relocated from their ministries to the Tuileries Palace, where Marmont had his command.26 But this seems to have been in the interests of safety, not efficient coordination with Marmont — once in the Tuileries, the ministers sat around and did nothing. In his memoirs, Haussez wrote acidly of how his fellow ministers behaved in this moment of crisis:

[Polignac] was dreamy; he paced the apartment, sat down at the desk, wrote, went out, returned, and answered none of the questions that were addressed to him. M. de Chantelauze, so energetic two days earlier, was lying on a sofa, overwhelmed and pensive. M. de Peyronnet, faithful to his character, treated with disdain the resistance whose seriousness was attested every instant by the sound of gunfire heard from all sides… M. de Ranville seemed to take upon himself the task of irritating our impatience by the flood of bad jokes with which he inundated us. Each event, each word, inspired a fancy that we had not previously known in him.27

It was the worst of both worlds from a leadership perspective: the ministers believed they had handed all authority over to Marmont, but Marmont still considered himself subject to the decisions of the ministers.28 The absurdity would be painfully demonstrated Wednesday afternoon, when a delegation of opposition deputies arrived to talk to Marmont.

“Not a very bold defiance”

After two days of yapping, a group of opposition deputies had met again around noon on Wednesday. Importantly, new deputies had begun to arrive, politicians with more aggressive temperaments than Casimir Périer or André Dupin. Chief among these newcomers were the liberal banker Jacques Laffitte, and the aging revolutionary lion, the Marquis de Lafayette. One attendee called for the deputies to establish a provisional government — effectively declaring the king’s ministry to be overthrown in a revolution. That was too much for the assembled deputies, who instead voted to send a delegation to Marmont: five men including Laffitte and Périer. At this time François Guizot piped up that he had finished writing the declaration he had been assigned to write the day before.29 On the one hand, this protest was littered with deferential phrases, about deputies being “inviolably faithful to their oath to the king” and blaming Four Ordinances on evil counsellors “deceiving the intentions of the monarch”; on the other hand, it very firmly declared the Four Ordinances unconstitutional and promised that the deputies “will not cease to protest” even if faced with physical force.30

After two days of yapping, a group of opposition deputies had met again around noon on Wednesday. Importantly, new deputies had begun to arrive, politicians with more aggressive temperaments than Casimir Périer or André Dupin. Chief among these newcomers were the liberal banker Jacques Laffitte, and the aging revolutionary lion, the Marquis de Lafayette. One attendee called for the deputies to establish a provisional government — effectively declaring the king’s ministry to be overthrown in a revolution. That was too much for the assembled deputies, who instead voted to send a delegation to Marmont: five men including Laffitte and Périer. At this time François Guizot piped up that he had finished writing the declaration he had been assigned to write the day before.29 On the one hand, this protest was littered with deferential phrases, about deputies being “inviolably faithful to their oath to the king” and blaming Four Ordinances on evil counsellors “deceiving the intentions of the monarch”; on the other hand, it very firmly declared the Four Ordinances unconstitutional and promised that the deputies “will not cease to protest” even if faced with physical force.30

Above: Jacques Laffitte, unknown artist, circa 1830-1844. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This document has been interpreted in different ways by different historians, with Vincent Beach calling it “a very weak statement” which showed that the deputies ”were very reluctant to do anything that might endanger their privileged positions.”31 David Pinkney notes that while it was “not a very bold defiance compared to the violence in the streets,” it was “a commitment to resistance nonetheless.”32

With this declaration in hand, Laffitte and Périer and their companions went to meet Marmont at the Tuileries Palace. This visit took some courage, and not just from navigating the war zone that was central Paris. Before they set out, Périer said, “I fear that we are going to walk into a trap” — and indeed the ministers had given Marmont a list of deputies who were to be arrested that included Laffitte and a second member of the delegation. With Paris under martial law, Marmont had the legal authority to have had soldiers seize the delegation, try them before an impromptu military court, and have them summarily shot.33

Above: The Tuileries Palace (foreground) with the Louvre behind, in 1850. By Charles Fichot, 1860. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Meeting the marshal

Fortunately for the deputies, Marmont had neither the interest nor the stomach for such bold action. Marmont told Polignac that “it would be a grave error” to arrest men on a diplomatic mission, and notes in his memoirs that Polignac gave no response to this argument.34 Instead, Marmont welcomed the deputies in to his office around 2:30 p.m., and heard them out. The deputies asked Marmont to pull his soldiers back and stop fighting. Marmont, as I related in Episode 42, told the deputies that he sympathized with them but that he had orders to suppress the insurrection. Marmont would be happy to order a cease-fire — as soon as the insurgents laid down their arms first. Given how spineless the opposition deputies had been until this point, I was actually kind of impressed by their response: they told Marmont that they could not ask the people of Paris to stop fighting unless Charles rescinded the Four Ordinances and dismissed the Polignac ministry. Marmont, who very much did not want to be in the middle of this, said he had no power to take this step himself. He offered to forward their request to King Charles. But in the meantime, Marmont asked, maybe they could talk to Polignac, who was hanging out in the next room?35

Fortunately for the deputies, Marmont had neither the interest nor the stomach for such bold action. Marmont told Polignac that “it would be a grave error” to arrest men on a diplomatic mission, and notes in his memoirs that Polignac gave no response to this argument.34 Instead, Marmont welcomed the deputies in to his office around 2:30 p.m., and heard them out. The deputies asked Marmont to pull his soldiers back and stop fighting. Marmont, as I related in Episode 42, told the deputies that he sympathized with them but that he had orders to suppress the insurrection. Marmont would be happy to order a cease-fire — as soon as the insurgents laid down their arms first. Given how spineless the opposition deputies had been until this point, I was actually kind of impressed by their response: they told Marmont that they could not ask the people of Paris to stop fighting unless Charles rescinded the Four Ordinances and dismissed the Polignac ministry. Marmont, who very much did not want to be in the middle of this, said he had no power to take this step himself. He offered to forward their request to King Charles. But in the meantime, Marmont asked, maybe they could talk to Polignac, who was hanging out in the next room?35

Above: Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin, portrait of Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont, Marshal of France, 1837. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Laffitte and the others agreed, so Marmont went into the next room to talk to Polignac. There followed a “long, whispered conversation” of around 10 minutes. Eventually, Marmont came back to tell the deputies that Jules de Polignac, the king’s prime minister, thought meeting with the leaders of the opposition in the middle of a revolution would be pointless. The only person who could agree to the concessions the opposition wanted was miles away in the suburban palace of Saint-Cloud: King Charles.36

Laffitte and the others agreed, so Marmont went into the next room to talk to Polignac. There followed a “long, whispered conversation” of around 10 minutes. Eventually, Marmont came back to tell the deputies that Jules de Polignac, the king’s prime minister, thought meeting with the leaders of the opposition in the middle of a revolution would be pointless. The only person who could agree to the concessions the opposition wanted was miles away in the suburban palace of Saint-Cloud: King Charles.36

Left: King Charles X of France in a military uniform, by Thomas Lawrence, 1825. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And so, as men continued to die in the boulevards, the political momentum shifted almost by default to Charles. Marmont, as he promised, immediately dispatched an aide with a message for the king. In it, Marmont described the situation: he thought at this point that his attack columns had achieved their objectives, but was under no illusions that that would be enough to win. As he put it to the king, he recognized “the increasing gravity of the military position in Paris.” Marmont described the demands of the opposition deputies, and added a postscript: “I think it is urgent that your majesty exploit without delay the overtures which have been made.”37

“We won’t lack for signers”

Unfortunately for Marmont, it appears that Polignac dispatched a message to Charles at the same time with the opposite message: continue the fight.38 We’ll come back to Charles later, though, and instead follow the opposition leaders as they reported back. The assembled deputies, frustrated and divided, decided there was little they could do but wait for a reply from the king. In the meantime, they heard back from the newspaper editor they had asked to print Guizot’s declaration — the same man who had defied the police for hours on Tuesday morning, when they came to disable his printing press for publishing the Protest of the Forty-Four. This editor — who had repaired his press — informed the deputies that in light of the ongoing fighting, he had made a few edits to their declaration: removing all the usual deferential forms of address to the king. And furthermore, the editor refused to print the declaration without signatures.39

The signatures proved a big stumbling block, with many deputies unwilling to actually put their names on a statement of defiance against the king. The opposition deputies were getting more radical as the fighting continued, but on Wednesday afternoon — with Marmont’s troops still occupying their positions in central Paris — most were unwilling to embrace full revolution. Some more conservative opposition deputies walked out of the meeting, where they were harangued by nearby Parisians for their unwillingness to fight.40 Others talked still, after two days of street fighting, of the original tax strike plan.41 Some, like Périer, were trying desperately to save Charles’s throne. “The best thing for France is the Bourbons without the Ultras,” Périer argued on Wednesday.42 It was arguably a more valiant and creative effort to keep Charles as king than anything his own ministers were doing. But events in the streets were sweeping everyone onward. Increasing numbers of opposition deputies were ready to endorse more radical steps, and were only holding back due to fear — either fear for their personal safety, or fear that a precipitous move might prove a mistake.

The dilemma of the signatures went on embarrassingly long, and ultimately had to be settled with a face-saving compromise. The manifesto would print the names of the deputies who had been present at the meeting without actually stating that they endorsed it. A cynical Laffitte observed that “in this way, if we are defeated, no one will have signed; and if we win, we won’t lack for signers.” But at this exact moment on Wednesday afternoon, even the more radical voices weren’t prepared to go all the way. The fighting had been fierce, but it looked like Marmont might be winning. His troops still occupied their positions in central Paris, and reinforcements were expected the next day. There had been no serious defections by the regular troops, who had instead obeyed orders and fired on the crowds. Meanwhile there were corpses on the streets of Paris, driving home the costs of rebellion. On Wednesday night, the radical deputy Auguste Bérard went to bed with loaded pistols at his bedside table and an escape route planned through his neighbor’s house, so worried was he about soldiers coming for him in the night.43

But what few of the politicians — neither the opposition leaders nor the ministers — recognized yet was just how badly Wednesday’s fighting had gone for Marmont’s troops, who stumbled back to the Tuileries with their wounded after midnight. The people of Paris had won. And that meant the balance of power on Thursday was going to change.

Orléans

As Wednesday drew to a close, a few deputies had already come to this realization. Lafayette, impatient at the timidity of his fellow deputies, went out late Wednesday to see the barricades for himself. He was initially challenged by an armed civilian until being recognized: “It’s General Lafayette!” Pleased, the old general responded, “To arms, gentlemen!” and inspected them as if he were their commander. This wasn’t just a nostalgic gesture — Lafayette had already been approached by insurrectionaries asking him to lead the revolution. By Wednesday night, Lafayette was prepared to accept.44

Meanwhile Jacques Laffitte had waited all day for Charles to send a response to their delegation. By 10 p.m., no word had come. For Laffitte and others of the bolder type of opposition leader, this silence was itself a message — a declaration of war. One of Laffitte’s allies declared that “we have had enough of idle talking — the time is come to act. Let us show ourselves to the people, and in arms.”45 Laffitte had offered Charles an easy way out: get rid of the ministers and the Four Ordinances, and Charles could stay king with a new, more liberal ministry. Now Laffitte’s circle of politicians finally accepted a more radical — a more revolutionary — plan: they would get rid of Charles, too.

Conveniently, Laffitte had a replacement in mind: the king’s cousin, Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans.46

Conveniently, Laffitte had a replacement in mind: the king’s cousin, Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans.46

Right: Louis-Philippe, by Ary Scheffer, 1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

There were a few problems with this plan. No one knew where Louis-Philippe was — and no one knew whether he would agree to usurp his cousin and become king.

Next time, we will turn our gaze at last to France’s royal family. What exactly has Charles been up to at Saint-Cloud while his soldiers fought and died? Will Louis-Philippe come out of the shadows? Will the people of Paris press their attack on Marmont’s battered brigades? Will the rest of the opposition politicians finally take that decisive step from protest to revolution? It all comes together in a climactic showdown that will decide the fate of a dynasty. So please join me next time for Episode 44: Bourbons on the Rocks.

-

David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 79. “It appears that [a coup d’état] has been renounced for the moment,” Lafayette wrote on July 26, from his country estate of La Grange. At that moment, 60 kilometers away, Parisians had already discovered the Four Ordinances. ↩

-

Baron d’Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, Dernier Ministre da la Marine sous la Restauration, vol. 2 (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1897), 232-3. David Pinkney notes that no other source outside of Charles’s ministers backs up this accusation. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 258. ↩

-

Daniel L. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827-30 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 124-138. ↩

-

In this letter, Broglie wrote that “the wind still seems to threaten a coup d’état,” but that he was sure “that will only be be resorted to after the meeting of the Chambers.” Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 124-7. Achille-Léon-Victor, duc de Broglie, Personal recollections of the late Duc de Broglie, 1785-1820, ed. and trans. Raphael Ledos de Beaufort, vol. 2 (London: Ward and Downey, 1887), 305-6. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 86. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 89. ↩

-

Comtesse de Boigne, Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne: 1820-1830, Vol. 3, ed. Charles Nicoullaud (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 262. ↩

-

Robert Tombs, France 1814-1914, Longman History of France (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 26-31. ↩

-

Alan Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes: The French Carbonari Against the Bourbon Restoration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), 150-2. Robert Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition: Liberal Opposition and the Fall of the Bourbon Monarchy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 143-4. ↩

-

Alexander, Re-writing the French Revolutionary Tradition, 289. ↩

-

Vincent W. Beach, Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1971), 364. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 223. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 364. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 87-9. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 247-9. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 249-50. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 250-1. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 91-2. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 250-1. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 91-2. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 93. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 96-7. See also Charles de Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, tome II: La Restauration ultra-royaliste, la Révolution de Juillet (1820-1832), ed. Charles-H. Pouthas (Paris: Plon, 1959), 323-4. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 96. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 371. ↩

-

Rémusat, Mémoires de ma Vie, 327-8. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 97-8. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 97-8. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 367. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 256. ↩

-

Haussez, Mémoires du Baron d’Haussez, 258-9. Translation from Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 124-5. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 368-9. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 370. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 123. ↩

-

Louis Blanc, The History of Ten Years: 1830-1840, vol. 1, translator unknown (London: Chapman and Hall, 1844), 119. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 370-1. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 123-4. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 371. The second member with a warrant was General Étienne Gérard. ↩

-

Beach, Charles X of France, 371. Laffitte’s memoirs claim that Polignac himself threw the warrants into the fire, but other sources credit Marmont with refusing to carry them out and are clear that the deputies never met Polignac. Historian T.E.B. Howarth disparages Laffitte’s memoirs as “generally mendacious.” Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 234. T.E.B. Howarth, The Life of Louis-Philippe, Citizen-King (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1961), 151. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years, 122. Beach, Charles X of France, 371. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 125. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 125. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 126. Beach, Charles X of France, 372. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years, 123. Beach, Charles X of France, 372-3. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years, 124. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 127. Note that Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 235 presents a different narrative, in which the deputies themselves edit Guizot’s statement, but this appears to be an outlier and Rader provides no sourcing to back up this claim. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 127. ↩

-

Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 137. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years, 125. ↩

-

The choice of signatures went further than merely listing those present — it also included some deputies who weren’t present but who it was thought might have agreed had they been present. This, of course, merely muddied the waters further about who had endorsed what. Rader, The Journalists and the July Revolution in France, 235. Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 128-9. Blanc, The History of Ten Years, 124-5. ↩

-

Mike Duncan, Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution (New York: Public Affairs, 2021), 411-2. ↩

-

Blanc, The History of Ten Years, 128. ↩

-

Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830, 128. ↩