Episode 45: The July Revolution

On Thursday, the hunters became the hunted.

Marshal Marmont had given up on his attempt to impose order on Paris. Now the remnants of his shattered assault columns had pulled back to the heart of the city and hunkered down in defensive positions. The royal army now controlled just a few blocks of Paris: the Tuileries Palace, home to the king, and the neighboring Louvre Palace, already a museum filled with striking works of art. The Army also controlled, intermittently, the road leading west to the suburban palace of Saint-Cloud, where King Charles had been spending the fighting with his courtiers.1

All around them were Parisians, thousands upon thousands of them. They were angry, they were armed — and now they sensed victory. Men who hadn’t taken part in the fighting on Wednesday were now on the front lines, ready to drive the soldiers back to their master at Saint-Cloud.2

That was easier said than done, of course. Now the soldiers were the ones with cover, behind the walls and windows of the two palaces. The soldiers may not have had as much ammunition as they needed, but they had more rounds than the insurgents did. And they had artillery. One group of around 400 Parisians tried to cross the Seine on the Pont Royal, but got driven back by heavy fire from dug-in defenders. Another group gathered around the Louvre and took pot-shots at windows, but showed zero desire to launch a frontal assault. Marmont thought he could hold this position for three days, and nothing about the early fighting Thursday suggested he had been wrong.3

But Marmont’s advantage in firepower wasn’t going to win him the battle. The fighting of the past three days had always been about morale. And the swarms of outgunned insurgents had way more of that than did the embattled soldiers.

The first to crack were the soldiers of the regular Army. While the Royal Guardsmen had sought out service in their prestigious (and high-paid) unit, the infantry of the line were poorly paid conscripts. A few of them had already deserted on Wednesday. Now entire regiments who had fought and died for Marmont on Wednesday were unreliable. Men grumbled that they didn’t want to fight their fellow Frenchmen — or that they wouldn’t fight their fellow Frenchmen.4

The first to crack were the soldiers of the regular Army. While the Royal Guardsmen had sought out service in their prestigious (and high-paid) unit, the infantry of the line were poorly paid conscripts. A few of them had already deserted on Wednesday. Now entire regiments who had fought and died for Marmont on Wednesday were unreliable. Men grumbled that they didn’t want to fight their fellow Frenchmen — or that they wouldn’t fight their fellow Frenchmen.4

Right: Hippolyte Bellangé, “Vive la ligne! 29 juillet 1830,” Album patriotique (Paris: Gihaut, 1831)

The trouble started with the 5th and 53rd Regiments of the Line. They had been placed in the Place Vendôme, a city square strategically located to guard the left flank of the king’s army. But these conscripted soldiers had no motivation left to fight, and were increasingly fraternizing with the Paris civilians they were supposed to be guarding against.

The men of the 5th and 53rd regiments would probably have deserted eventually. But on Thursday morning, they got some help. With the whole detachment wavering, they received orders to attack a group of insurgents menacing Marmont’s position. The men were almost universally unwilling to obey this order — and neither were the officers. Instead, some of the officers sent a delegation to the house of opposition politician Jacques Laffitte, where they effectively asked to negotiate a surrender. Laffitte and the other opposition leaders gathered there had spent much of the past few days arguing among themselves, but by Thursday morning they were growing bolder. It was technically treason, but Laffitte wasn’t going to pass up this opportunity to weaken Charles and prevent bloodshed. Laffitte dispatched a veteran Army officer and his brother as envoys, who visited the mutinous soldiers and promised them that if they defected, they wouldn’t be asked to fight their comrades in Marmont’s army. That was all the men needed, and the two regiments marched en masse away from their position to Laffitte’s house. They were placed under the command of Étienne Gérard, an opposition deputy and former Napoleonic general, and took no further part in the hostilities.5

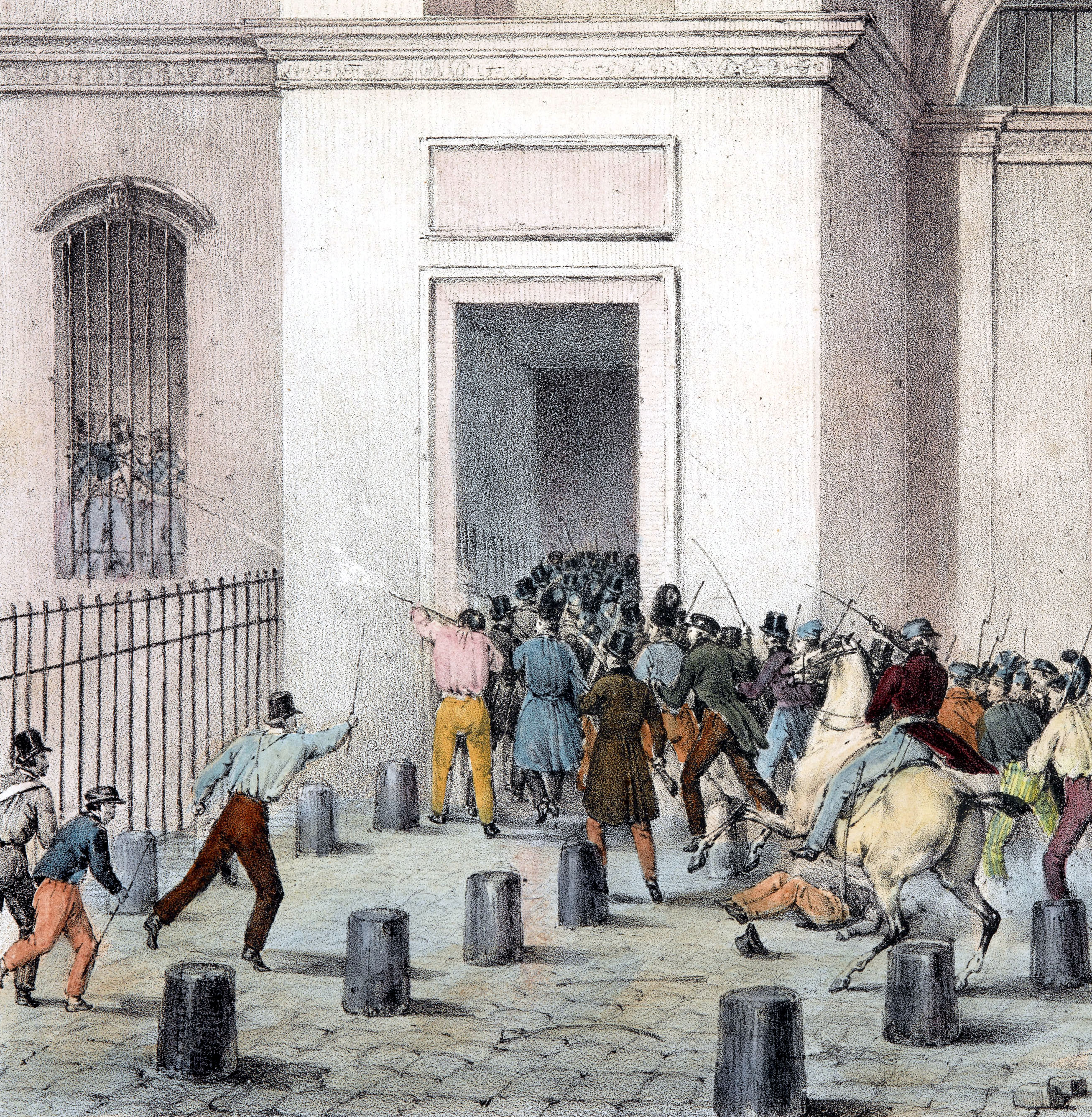

Below: Bernard-Édouard Swebach, detail from “Prise du Louvre,” in Semaine Parisienne: Fastes des Habitants de Paris, album national dédié aux braves qui ont combattu pour la liberté dans les journées des 27, 28, 29 juillet 1830 (Mulhouse and Paris: Engelmann et Cie, 1830). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Now, Marmont had known these men weren’t very reliable. He had placed them off on his flank and not at the center of his lines for a reason. But their surrender still was a huge blow — not least because it raised serious questions about two other regiments of line infantry6, who were holding a more critical position in the Tuileries Garden. So Marmont moved those line regiments to a less important spot on the Champs Elysée, and backfilled them with some of the Royal Guardsmen garrisoning the Louvre. Which in turn left the Louvre undermanned. The commander of the remaining Guards in the Louvre began to worry about getting overrun, so ordered a withdrawal to the Tuileries around 11 a.m. But as the retreating Guards crossed open ground, the insurgents began firing on them. The guards shifted from a march to a run. Then other troops saw the Guards running — and fearing the worst, began to run away too. A third unit of guards did the same thing. And suddenly, in almost no time at all, a controlled redeployment had turned into a complete rout. Marmont tried to personally rally the men and stop the retreat, but he was ignored. His soldiers — the lucky ones who weren’t trapped behind — fled down the Champs Elysée, out of central Paris, and out of the fight.7

Now, Marmont had known these men weren’t very reliable. He had placed them off on his flank and not at the center of his lines for a reason. But their surrender still was a huge blow — not least because it raised serious questions about two other regiments of line infantry6, who were holding a more critical position in the Tuileries Garden. So Marmont moved those line regiments to a less important spot on the Champs Elysée, and backfilled them with some of the Royal Guardsmen garrisoning the Louvre. Which in turn left the Louvre undermanned. The commander of the remaining Guards in the Louvre began to worry about getting overrun, so ordered a withdrawal to the Tuileries around 11 a.m. But as the retreating Guards crossed open ground, the insurgents began firing on them. The guards shifted from a march to a run. Then other troops saw the Guards running — and fearing the worst, began to run away too. A third unit of guards did the same thing. And suddenly, in almost no time at all, a controlled redeployment had turned into a complete rout. Marmont tried to personally rally the men and stop the retreat, but he was ignored. His soldiers — the lucky ones who weren’t trapped behind — fled down the Champs Elysée, out of central Paris, and out of the fight.7

Behind them, Parisians flooded into the Louvre and the Tuileries Palace. It was around noon on Thursday, July 29, 1830. The rebels held Paris.

So what happens next?

This is The Siècle, Episode 45: The July Revolution.

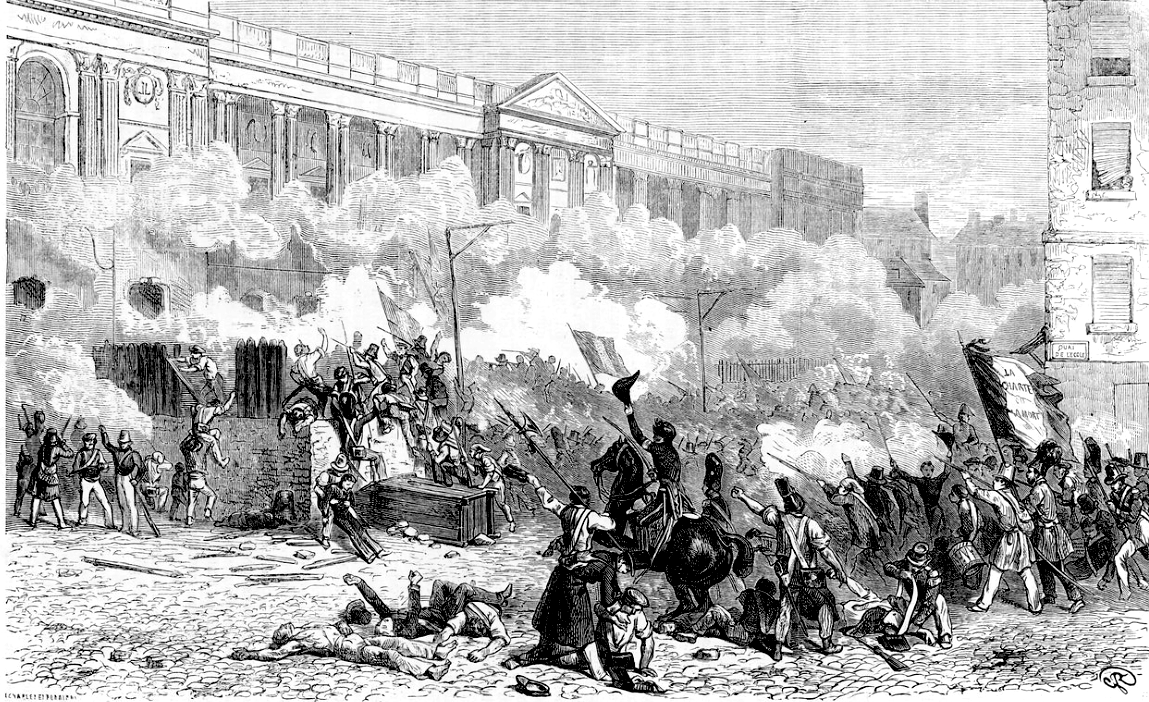

Gustave Roux, “Taking of the Louvre,” in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Welcome back, everyone! It’s been a while since the last episode, though I have a better excuse than usual for the delay: in February, my wife and I welcomed our first child. I had grand plans to finish this episode before her birth, and to pre-record a couple of interviews to release during those busy first few months. But then she arrived a few weeks early, and all my plans fell apart faster than Jules de Polignac’s attempt to suppress France’s liberal opposition via royal ordinances.

But while Polignac’s blunder brought a swift end to the regime he served, I’m happy to report that The Siècle lives on. Lots of things are going to change, of course, but that actually has less to do with the baby than it does with the events covered in this episode!

This is going to be the longest scripted episode of the show to date, so I’ll get into things quickly. First, though, I wanted to offer a special thanks to historian Munro Price, who generously helped me sort through a couple of tricky historiographical points. If you like this show, you might enjoy his work of popular history, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions. I also want to thank this show’s network, Evergreen Podcasts, and all of you for supporting the show. I especially want to thank the show’s loyal supporters on Patreon, who are helping me afford the exorbitant cost of American day care. New patrons since the last episode include: Eren, A.T., John Dusek, Matthew Bayer, Bogan, Garth, Colin Benthlen, Ashurbanipaul, Gains Murdoch, Rishi Wahi, Canadean, Tyson Woolman, Cheryl Kinkaid, J. Wayne Riggins and Brett Wooldridge. You can join them, and a get an ad-free feed of the show, for as little as $1 per month. Find out how at thesiecle.com/support.

Now, into the episode!

Those who show up

As Marshal Marmont retreated from Paris, he took with him the last vestige of the French government. The king was not in Paris. The army wasn’t in Paris. The police were gone. So were the ministers and the civil servants. So if all that was gone, who was in charge in Paris?

Into this leadership void stepped the rebel General Hugues Dubourg. Now, if you’re saying “who?” you’re not wrong to do so. General Dubourg was not in fact a rebel. He wasn’t a general. He wasn’t even properly named “Dubourg.” But Dubourg was present on the streets of Paris on Thursday morning, wearing a general’s uniform purchased from a second-hand clothing shop. “Long live General Dubourg!” cried crowds of Parisians who, like the rest of us, had never heard of Dubourg a minute ago. Backed by this crowd, Dubourg swept into the Paris city hall, the Hôtel de Ville, and started giving orders. And people started carrying them out. After all, someone needed to be in charge, and Dubourg at least looked the part.8

Other men soon followed Dubourg’s example and realized the value of just acting like you were in charge. Take Jean-Jacques Baude, who unlike Dubourg actually had some standing as a participant in the ongoing revolution. Baude was the editor of Le Temps, one of the opposition newspapers who had defied the Four Ordinances. In particular, Baude was the editor who padlocked his doors Tuesday morning and defied the police for hours, drawing an increasingly restive crowd. He showed up at the Hôtel de Ville and proclaimed himself to be “General” Dubourg’s secretary.9

The orders that came out of the Hôtel de Ville were serious stuff. They took inventory of the city treasury, checked with bakers on the bread supply, and ordered fresh cattle to be allowed into the city tax-free. They even met foreign diplomats!10 As the saying goes, the real decisions are made by those who show up.

But Paris on Thursday, July 29, 1830, was full of men who thought they should be in charge, even if few had the chutzpah of “General” Dubourg. That’s definitely true of France’s assembled opposition deputies — as we saw in Episode 43, no one could accuse them of boldness. But while they may have dithered, the deputies did have a certain legitimacy from winning elections. It was at least partially for these deputies that the crowds had fought these past three days. Unlike Dubourg, people had already heard of Jacques Laffitte, Casimir Périer, and General Étienne Gérard (a real general). And by Thursday, after Charles had rebuffed their attempts to negotiate and Marmont had been soundly beaten, the deputies began to finally assert themselves.

But Paris on Thursday, July 29, 1830, was full of men who thought they should be in charge, even if few had the chutzpah of “General” Dubourg. That’s definitely true of France’s assembled opposition deputies — as we saw in Episode 43, no one could accuse them of boldness. But while they may have dithered, the deputies did have a certain legitimacy from winning elections. It was at least partially for these deputies that the crowds had fought these past three days. Unlike Dubourg, people had already heard of Jacques Laffitte, Casimir Périer, and General Étienne Gérard (a real general). And by Thursday, after Charles had rebuffed their attempts to negotiate and Marmont had been soundly beaten, the deputies began to finally assert themselves.

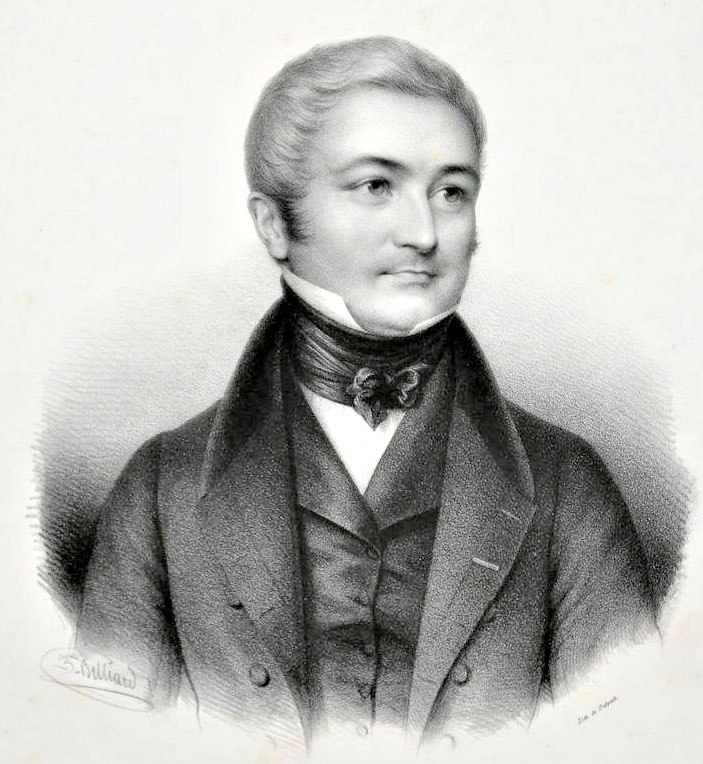

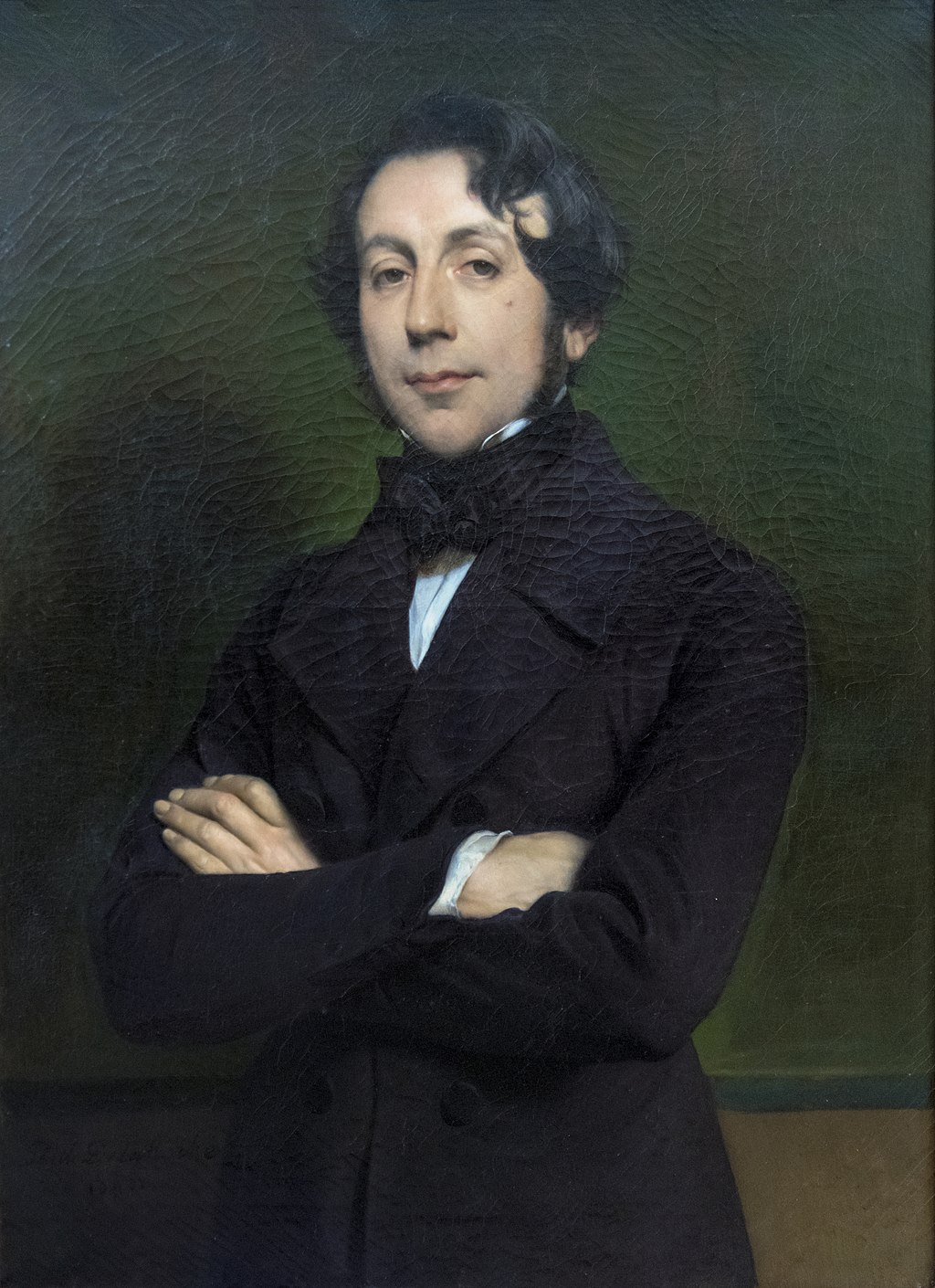

Right: Jacques Laffitte, unknown artist, circa 1830-1844. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The base of operations for the liberal opposition was the spacious townhouse of Laffitte, a wealthy banker and deputy. Laffitte’s house was — and still is — located just outside the great ring of Parisian boulevards. At the time the street was named the “Rue d’Artois,” but it will give you some sign of Jacques Laffitte’s significance that it is today called the “Rue Laffitte.” On Thursday morning, deputies “moved in and out of his open door, crowded his salons, and overflowed into the courtyard and garden.” The crowds also included a host of non-deputies, too: lawyers, businessmen, journalists, and more. Many of them were wearing ribbons with the banned revolutionary tricolor, to show their support for what was increasingly seeming like a genuine revolution.11

The Hero of Two Worlds

And if you’re holding a genuine revolution, one man was bound to show up: Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette — or “General Lafayette,” as he now preferred to be called instead of the aristocratic title “Marquis.” Lafayette had fought in the American Revolution as a young man. A decade later he had been a key leader in the 1789 French Revolution, where he invented the tricolor and commanded the Paris National Guard.12 And Lafayette has been active in our time period, too. In Episode 14 we saw him get elected to the Chamber of Deputies, and in Episode 15 saw Lafayette use this position to become a leading spokesman of the Left against Louis XVIII’s government. When legal opposition failed, Lafayette enthusiastically endorsed conspiracies to overthrow the regime, willingly lending his name to any revolutionary group that wanted him. We saw that in Episode 23. But when the Carbonari conspiracies failed and Lafayette lost his seat in parliament, Lafayette went abroad for a tour of the United States, where he was immensely popular, as covered in Episode 24. Reenergized, Lafayette came back to France and was elected to the Chamber of Deputies again in 1827, which we saw in Episode 31. In Episode 34 we saw King Charles warned about Lafayette’s popularity during a visit to Lyons. On Monday, July 26, 1830, Lafayette’s grandson-in-law, Charles de Rémusat, urgently summoned him back to Paris from his country estate with news of the Four Ordinances — events from Episode 40. By the evening of Wednesday, July 28, Lafayette was back in the city, where he was enthusiastically greeted by rebels manning a barricade, which I mentioned in Episode 43.

And if you’re holding a genuine revolution, one man was bound to show up: Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette — or “General Lafayette,” as he now preferred to be called instead of the aristocratic title “Marquis.” Lafayette had fought in the American Revolution as a young man. A decade later he had been a key leader in the 1789 French Revolution, where he invented the tricolor and commanded the Paris National Guard.12 And Lafayette has been active in our time period, too. In Episode 14 we saw him get elected to the Chamber of Deputies, and in Episode 15 saw Lafayette use this position to become a leading spokesman of the Left against Louis XVIII’s government. When legal opposition failed, Lafayette enthusiastically endorsed conspiracies to overthrow the regime, willingly lending his name to any revolutionary group that wanted him. We saw that in Episode 23. But when the Carbonari conspiracies failed and Lafayette lost his seat in parliament, Lafayette went abroad for a tour of the United States, where he was immensely popular, as covered in Episode 24. Reenergized, Lafayette came back to France and was elected to the Chamber of Deputies again in 1827, which we saw in Episode 31. In Episode 34 we saw King Charles warned about Lafayette’s popularity during a visit to Lyons. On Monday, July 26, 1830, Lafayette’s grandson-in-law, Charles de Rémusat, urgently summoned him back to Paris from his country estate with news of the Four Ordinances — events from Episode 40. By the evening of Wednesday, July 28, Lafayette was back in the city, where he was enthusiastically greeted by rebels manning a barricade, which I mentioned in Episode 43.

Above: Ary Scheffer, “Portrait of Lafayette,” 1823. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Now it’s Thursday, July 29, and after years of waiting and false starts, Lafayette was ready to star in his third revolution. He arrived at Laffitte’s house around midday Thursday, and told the assembled deputies that he had been offered command of the Paris National Guard. That was a bit surprising, because legally, there was no such thing as the “Paris National Guard.” King Charles X had summarily dissolved it in 1827, after some of its members had heckled him during a parade — I talked about that in Episode 31. But the disbandment had been done so hastily that the members of this citizen militia had kept their uniforms and even their guns. Now, with Paris in chaos, some former Guardsmen had dug their old uniforms out of their closet and appeared on the streets. Despite some later myth-making to the contrary, these National Guardsmen generally didn’t emerge to participate in the revolution by attacking Marmont’s soldiers. Instead, they mostly seem to have tried to keep order — and in particular, to guard their own private property.13

But the offer Lafayette brought to the politicians at midday Thursday wasn’t just about a handful of nervous bourgeois militiamen. There had been 20,000 National Guardsmen in Paris before the disbandment — more than the roughly 10,000 soldiers Marmont had had at his disposal at the start of the uprising.14 If the Guard reformed, it would be the most powerful military force in the city — and Lafayette told the deputies that he had been offered its command.

Who exactly had made this offer is harder to pin down, but it appears to have been just a couple of random National Guardsmen making the offer — not anyone with authority to speak for the Guard as a whole.15 But we know, none of that mattered, not this day. On Thursday, July 29, 1830, power went to those bold enough to accept it. Lafayette said yes.

Now, unlike Dubourg, Lafayette wasn’t seizing power unilaterally. That’s why he was here at Jacques Laffitte’s house, deferential but firm, telling a group of around 30 deputies that “an old name from [1789] can be of some use in the present grave circumstances.”16 But the realities of the situation were that Lafayette, one of the most radical members of the liberal opposition, had been offered effective military control of Paris. And now the opposition politicians, who have been paralyzed for days by disagreements between radicals and conservatives, were being asked to sign off on it.

And the politicians did! If the deputies were concerned about putting so much power in the hands of one man, they were also concerned about chaos and disorder in the capital — especially when word came, as Lafayette was talking to them, that the Tuileries had fallen and Marmont fled. In this sudden anarchy, a revived National Guard, comprised of middle-class, property-owning Frenchmen, might be a force in Lafayette’s hands — but it also might be a force for order.17

The deputies did more than just rubber-stamp Lafayette, though. They also, finally, took a step to assert their own claim on power. One of them, François Guizot, proposed the creation of a provisional municipal government, to replace the departed prefects and ministers. They offered Lafayette the ability to appoint its members — an offer they probably had to make, since any municipal government would rely on Lafayette’s Guardsmen to carry out its decrees. But Lafayette declined the offer. So the deputies began appointing themselves. Jacques Laffitte turned down an appointment, seeing himself having more influence as a political leader than he would as an administrator. So did General Étienne Gérard, citing his role commanding the turncoat regiments of the line. But five men, including Casimir Périer, did accept appointments. Befitting the divided nature of the opposition, the five men included two radicals who wanted to push the revolution forward, two conservatives who wanted to rein it in, and one moderate in between.18

But division was for the future. At the moment, Lafayette was the man of the hour. Along with the newly appointed municipal commissioners, Lafayette set out for the Hôtel de Ville — about 1.7 miles or 2.7 kilometers from Laffitte’s house. The walk turned into a parade of sorts, with people pressing in everywhere around Lafayette, cheering, and helping the 72-year-old general over the dozens of barricades that blocked the way. The crowd outside the Hôtel de Ville was bigger and more raucous, with loud ovations and muskets fired into the air in celebration. Against this wave of acclaim, a mere adventurer like “General” Dubourg was helpless. Dubourg, whose birth name was “Fouchard,” had switched sides repeatedly over a long career between royalist, republican, and imperial causes; he knew when to jump ship, and graciously handed over his self-assumed power to Lafayette. This new city government — acting a lot like a national government — formally re-summoned the National Guard, appointed prefects, and began issuing a flurry of orders.19

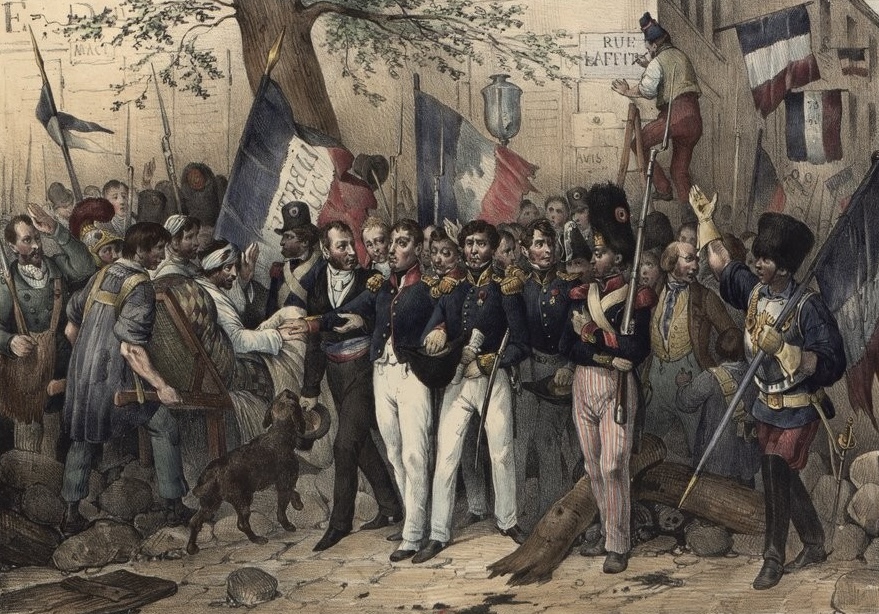

Victor Adam, “General Lafayette Goes to the Hôtel de Ville, Accompanied by Mssrs. Audry de Puyraveau, Carbonnel, Gérard, Lafitte, de la Borde, Lasteyries (sic), Dumoulin, Béranger, etc.,” 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bonapartists and Republicans

But there were other claims to power in the anarchy after Marmont’s retreat. Some men had the same idea as Dubourg, and tried to simply declare who was in charge. For example, one group which included the liberal songwriter Pierre-Jean de Béranger — featured in Supplemental 17 — wrote out a declaration of a new provisional government that they somehow managed to persuade the newspaper Le Constitutionnel to publish. As the contemporary writer Louis Blanc put it, news “spread through Paris… of a government which existed only in the minds of some courageous forgers.”

This boldness stands in stark contrast to the caution of many prominent Parisians who maybe could have seized power if they wanted to. Take the liberal Duc de Choiseul, who picked up Le Constitutionnel and was horrified to see his name mentioned as part of this alleged new provisional government. Rather than embrace this supposed promotion, Choiseul hastily published a denial. The hesitant General Gérard was told by allies that if he was smart, he had better put on his uniform, get on a horse, and go let the people see him visiting the barricades.20

Besides these aggressive adventurers and nervous notables, though, were Parisians with more consequential ambitions — men who didn’t just want power for power’s sake, but who had an actual vision for France they wanted to implement. Of these, three were particularly important: the Bonapartists, the republicans, and the Orléanists.

There were plenty of Bonapartists in Paris, men who wanted to bring back the Napoleonic empire. Napoleon had been dead for nine years, of course, but he had a son who Bonapartists acclaimed as Napoleon II. The 19-year-old Bonaparte heir was inconveniently hundreds of miles away, a quasi-prisoner in the court of his mother’s father, the Austrian Emperor Francis I. But that didn’t stop thousands of Parisians from shouting “Long live Napoleon!” and “Long live the Emperor!” during the street fighting. Cries like “long live the Charter!” were more common, but Bonapartist chants were “probably… the most frequently heard political cries fixed on any individual.” Lots of these Parisians fighting on the barricades while calling for the Emperor were veterans of Napoleon’s armies. So there was absolutely potent Bonapartist sentiment on the streets of Paris. But channeling it was difficult. Many prominent men in Paris liked the idea of a restored Empire — but most of them were leery about the risks. Proclaiming an emperor living half a continent away under the control of a rival was a risky proposition. And the last time a Bonaparte sat on the throne of France, all the great powers of Europe had responded by invading. Crowning Napoleon II could very well bring war to France once again.21

There were plenty of Bonapartists in Paris, men who wanted to bring back the Napoleonic empire. Napoleon had been dead for nine years, of course, but he had a son who Bonapartists acclaimed as Napoleon II. The 19-year-old Bonaparte heir was inconveniently hundreds of miles away, a quasi-prisoner in the court of his mother’s father, the Austrian Emperor Francis I. But that didn’t stop thousands of Parisians from shouting “Long live Napoleon!” and “Long live the Emperor!” during the street fighting. Cries like “long live the Charter!” were more common, but Bonapartist chants were “probably… the most frequently heard political cries fixed on any individual.” Lots of these Parisians fighting on the barricades while calling for the Emperor were veterans of Napoleon’s armies. So there was absolutely potent Bonapartist sentiment on the streets of Paris. But channeling it was difficult. Many prominent men in Paris liked the idea of a restored Empire — but most of them were leery about the risks. Proclaiming an emperor living half a continent away under the control of a rival was a risky proposition. And the last time a Bonaparte sat on the throne of France, all the great powers of Europe had responded by invading. Crowning Napoleon II could very well bring war to France once again.21

Above: Leopold Bucher, “Napoleon II, also known as Franz, Duke of Reichstadt,” 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Less numerous but more organized than the Bonapartists were the republicans, left-wing activists who wanted to abolish the monarchy and restore a French republic. Republican journalists and activists put their bodies on the lines, participating in the thick of the fighting on the barricades. Some were killed or wounded. But when radical writers like Auguste Fabre tried to persuade their comrades from the barricades to demand a republic, they found few takers. On Wednesday, Fabre and his fellow republicans tried to get their fellow insurgents to stop chanting “Long live the Charter!” in favor of other chants, like “Long live liberty!” that didn’t endorse constitutional monarchy. But they had no success. Months before, Fabre had formed a secret revolutionary society to fight for a republic, but while it had lots of students among its ranks, there appear to have been no ordinary workers. So it’s not surprising that republicans found little popular support for a new republic in 1830.22

That’s not to say the republicans were powerless. They had organization and a common cause, printing presses to spread their ideas, and their leaders had revolutionary credentials from participating in the street fighting. And while no actual workers had joined their secret republican society, someone who had joined was none other than General Lafayette — a famous admirer of the republican United States of America. Lafayette’s support for a new French republic was more symbolic than real, and no one knew where Lafayette would come down if push came to shove, but on Thursday, July 29, there was no better man in Paris to have at least theoretically on your side.23

We’ll be circling back to the Bonapartists and republicans soon to see what they do, because it’s time to focus on the single most organized group in Paris on Thursday afternoon: the Orléanists.

Orléanists

This is a group we’ve already met: the men who wanted to keep France a constitutional monarchy, but replace the ultraroyalist King Charles X with his more liberal cousin, Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans. There were plenty of people among the opposition deputies, and in the broader circle of opposition activists, who were sympathetic to the Duc d’Orléans as a new king. Louis-Philippe seemed like an ideal solution: as a man of royal blood but liberal ideas, a King Louis-Philippe could let France keep the conservative constitutional monarchy of the Charter. Unlike Charles X, Louis-Philippe wouldn’t try to undermine the Charter by going too far to the right — but they also thought he could be trusted not to undermine the Charter by moving too far to the left.

This is a group we’ve already met: the men who wanted to keep France a constitutional monarchy, but replace the ultraroyalist King Charles X with his more liberal cousin, Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans. There were plenty of people among the opposition deputies, and in the broader circle of opposition activists, who were sympathetic to the Duc d’Orléans as a new king. Louis-Philippe seemed like an ideal solution: as a man of royal blood but liberal ideas, a King Louis-Philippe could let France keep the conservative constitutional monarchy of the Charter. Unlike Charles X, Louis-Philippe wouldn’t try to undermine the Charter by going too far to the right — but they also thought he could be trusted not to undermine the Charter by moving too far to the left.

Left: Pierre Roch Vigneron, “Portrait of Louis-Philippe,” 1831. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But if Louis-Philippe was an appealing leadership candidate on paper, there were a few potential huge roadblocks. For one thing, relatively few people were enthusiastic about the Orléanist solution. No one was chanting “Long live Louis-Philippe” on the barricades! And even among the political elite, lots of men who had Orléanist sympathies were afraid to bite the bullet and actually offer Louis-Philippe the crown. It was treason to try to replace King Charles, and it was especially treason to try to bypass the normal line of succession through Charles’s son, the Duc d’Angoulême, and Charles’s grandson, the Duc de Bordeaux. And since the Orléanists tended to be people of property and stature, most of them were especially hesitant to gamble all of that on a potentially chaotic regime change.

The other big obstacle for the Orléanists was Orléans. Louis-Philippe was almost certainly not among the men trying to put him on the throne. He had made his peace with Charles and the Bourbon Restoration, and had spent the past few days of revolution trying to keep his head down and avoid attracting any attention. Which was all very well and good for Louis-Philippe’s personal safety, but as we saw with the Duc de Choiseul, it does no good to proclaim a government if your proclaimed leaders don’t want any part of it.

Below: François-Séraphin Delpech after Zéphirin Belliard, “Adolphe Thiers,” circa 1830s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Up against these obstacles were a handful of major Orléanist leaders. The most important of them was Jacques Laffitte, who had been bankrolling pro-Orléans newspapers like Le National. Another prominent Orléanist was Adolphe Thiers, the energetic 33-year-old journalist who was the National’s star writer, and who had helped kick off the entire revolution by drafting the Protest of the Forty-Four on Monday afternoon. The other name I’ll mention, just briefly, was Horace Sébastiani, a Corsica-born former Napoleonic general — a close friend of both Louis-Philippe and his sister Adelaide, but much less decisive than either Laffitte or Thiers.24

Up against these obstacles were a handful of major Orléanist leaders. The most important of them was Jacques Laffitte, who had been bankrolling pro-Orléans newspapers like Le National. Another prominent Orléanist was Adolphe Thiers, the energetic 33-year-old journalist who was the National’s star writer, and who had helped kick off the entire revolution by drafting the Protest of the Forty-Four on Monday afternoon. The other name I’ll mention, just briefly, was Horace Sébastiani, a Corsica-born former Napoleonic general — a close friend of both Louis-Philippe and his sister Adelaide, but much less decisive than either Laffitte or Thiers.24

For Laffitte, Thiers, and Sébastiani, the most important issue was getting Louis-Philippe on board. So on Thursday afternoon, they sent a back-channel message through the duke’s private secretary, urging him to accept the throne — or to face being exiled by a Bonapartist or republican government. It was a choice, Laffitte argued, between a crown and a passport. But the indecisive Louis-Philippe responded to this plea with three frustratingly noncommittal words: “I thank you.”25

This was not the “yes” that the Orléanists wanted. But it was also not a “no,” either. So in the meantime Laffitte and Thiers decided to forge onward and tackle their other problem — the lack of popular support. On Thursday evening, Thiers26 wrote and printed a manifesto to be plastered all over the city. This is the Orléanist manifesto I read in Episode 44, full of false or premature claims like “The Duc d’Orléans is a prince devoted to the cause of the Revolution,” or “The Duc d’Orléans has declared himself,” or that “it is from the French people that he will hold his crown.” On Thursday, July 29, bold men didn’t let the facts get in the way of their claims to power.

Of course, successful men also had to make sure their bold claims eventually came true. And so rather than just wait and see, Laffitte and his colleagues dispatched Thiers late Thursday night to go and find Louis-Philippe and convince him to get off the fence. I told that story at the end of Episode 44. There we saw Thiers fail to find the hiding Louis-Philippe, but he did talk to Louis-Philippe’s sister Adelaide and convince her to put her own name behind the effort to crown her brother.

But by the time Adelaide d’Orléans made her move, it was mid-morning on Friday. Precious hours had ticked by — hours where events weren’t standing still. Because in the meantime, one final player had entered the game. As Lafayette and Laffitte, Orléanists and Bonapartists, republicans and adventurers all scrambled for control of Paris, King Charles X at long last decided to negotiate.

King’s gambit

As we saw in Episode 44, news of Marmont’s retreat reached Charles at his suburban palace of Saint-Cloud on Thursday afternoon. With extreme reluctance, Charles agreed to fire his ultraroyalist prime minister Jules de Polignac and appoint the moderate Duc de Mortemart as the head of a new government. But Charles was still hoping to concede as little as he could get away with — which meant that he initially refused to put any of these concessions in writing. Mortemart, who was ill with a fever, in turn refused to leave without getting everything written down. This stalemate continued into the night Thursday as Charles’s throne hung in the balance.

In the meantime, Charles did dispatch messengers to Paris to inform the opposition that he was backing down. His messengers were three of the royalist nobles who had spent hours Thursday trying to persuade Charles to make concessions. Two of them we met in Episode 44: Baron Eugène de Vitrolles and Marquis Charles de Sémonville; with them was a third man, Comte Antoine d’Argout. (I realize I’m hitting you with a lot of names in this episode. Just bear with me here.)

It was early Thursday evening by the time the three nobles left Saint-Cloud, and their voyage was not easy. For one thing, they had spent all afternoon at Saint-Cloud, and knew nothing of what was going on in Paris. Once they reached the city’s outskirts, they had to make inquiries to find out who exactly was in charge — and were directed to the Hôtel de Ville. But getting there required navigating the barricades, each of them manned by “a throng of dangerous-looking men” who swarmed around the king’s emissaries, threatening and insulting them. This would have been disconcerting to anyone, but must have been especially unnerving to wealthy nobles who were used to their social status protecting them from this kind of harassment. It was Thursday, July 29, 1830, the third of what will soon be named the “Three Glorious Days,” and to the common people of Paris went the privileges of victory. Vitrolles, Sémonville, and Argout just had to take it.27

The three managed to make it all the way to Hôtel de Ville unharmed, but so far their message of royal concessions had not been met with the joy they might have been hoping for. There were a few cries of “Long live the king!” when the nobles explained what they were doing, but far more cries of “Long live the Charter!” or “Long live the Emperor!”28 The liberal politician Benjamin Constant was among many present who thought the mob was about to declare a republic.29

So it was with some relief that the nobles finally got inside the Hôtel de Ville and discovered that the men in charge there weren’t angry workers or radical students but fellow elites: Lafayette, Casimir Périer, and four other members of the municipal commission who are very important in all this but whose names I will spare you. The royal emissaries were greeted “as old friends” and “politely listened to.” But here again, there was no celebration or relief from the assembled opposition leaders. “It is too late!” said one.30 Another commissioner asked Charles’s emissaries a pointed question: “Have you written powers?”31 And of course they had nothing in writing from Charles — just verbal promises. At this hour, that just wasn’t enough, and the municipal commission declined to do anything with the offer.32

But that was no matter — there was more than one power in Paris. So it was off to Jacques Laffitte’s house. Or at least, the Comte d’Argout went to Laffitte’s. Sémonville was either too exhausted or too dismayed to make the trip — my sources differ — and everyone seemed to agree that Vitrolles’s history of ultraroyalism might prove less than constructive in the current environment, so he went back to Saint-Cloud. Argout, a liberal member of the Chamber of Peers, went off alone.33

When Argout finally arrived at Laffitte’s, sometime around 9 p.m., he found the house packed. As Louis Blanc sets the scene: “The heat was suffocating, the windows were open, and the rooms were full of people.” Argout told Laffitte the good news: “The ordinances are withdrawn, and we have a fresh ministry.” Laffitte replied coolly: “This decision should have been taken sooner.” Argout tried to protest, and Laffitte cut him off: “The situations are changed. A century has elapsed within 24 hours.” But the deputies agreed to talk. They told Argout they would wait until 1 a.m. that night, and that he should bring Mortemart there without delay.34

There was a delay. Argout, slowed by the same array of barricades that were impeding everyone’s travel through Paris, didn’t even make it back to Saint-Cloud until 1:30 a.m. He found the palace dark. Charles, Angoulême, Polignac, Marmont, the royal court — all were contentedly sleeping. Mortemart, at least, was still awake — still lacking the written proof of Charles’s concessions — and was spurred into action by the report from the city. Secretaries were woken up and made to take dictation of new ordinances: one formally appointed Mortemart as prime minister, with Casimir Périer as minister of finance and General Gérard as Minister of War; another formally annulled the Four Ordinances; and a third formally reestablished the Paris National Guard. That done, Mortemart, Argout, and Vitrolles went to do something very much against royal protocol: wake the king up in the middle of the night and make him sign them.35

Below: Artist unknown, “Casimir de Rochechouart, 11th Duke of Mortemart,” date unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As you can imagine, this did not go well. Royal functionaries tried to keep the nobles out. Once they were bypassed, Charles was upset — not just at being woken up in the middle of the night, but at the scale of the concessions he was being asked to sign. He “found one reason after another for delay,” and particularly objected to re-establishing the National Guard. Vitrolles told Charles that if he didn’t restore the National Guard, then Lafayette would do it. Either way, the National Guard would be back — better to at least claim it was his idea. Finally, worn down, Charles asked for the new ordinances and signed them without reading them. But by now it was close to dawn on Friday, July 30, 1830. Longer, still, before Mortemart managed to find a carriage and horses to take him into Paris, and longer yet before he could talk his way past the barricades. By the time Mortemart reached Jacques Laffitte’s house, it was 10 a.m. — nine hours after the deadline the deputies had set the night before.36

As you can imagine, this did not go well. Royal functionaries tried to keep the nobles out. Once they were bypassed, Charles was upset — not just at being woken up in the middle of the night, but at the scale of the concessions he was being asked to sign. He “found one reason after another for delay,” and particularly objected to re-establishing the National Guard. Vitrolles told Charles that if he didn’t restore the National Guard, then Lafayette would do it. Either way, the National Guard would be back — better to at least claim it was his idea. Finally, worn down, Charles asked for the new ordinances and signed them without reading them. But by now it was close to dawn on Friday, July 30, 1830. Longer, still, before Mortemart managed to find a carriage and horses to take him into Paris, and longer yet before he could talk his way past the barricades. By the time Mortemart reached Jacques Laffitte’s house, it was 10 a.m. — nine hours after the deadline the deputies had set the night before.36

In a new indignity, Mortemart found Laffitte’s house empty. After days spent meeting furtively in private homes, the deputies had taken a dramatic step: they had adjourned to reconvene at the Palais-Bourbon, the official meeting place of the Chamber of Deputies. Formal decisions were about to be made.37

Unfortunately for Mortemart, he would not be there when they got made. One deputy, the radical Auguste Bérard, saw the exhausted Mortemart and invited him in for refreshments. There Bérard explained — in an increasingly common refrain — that it was “too late” — “What I regarded as difficult yesterday is impossible today.” Mortemart argued that Charles had rights as king, and more practically that overthrowing Charles would invite foreign invasion. Bérard waved this off, saying that the choice was no longer between Charles and Louis-Philippe, but between Louis-Philippe and a republic.38

The thing is, Bérard was bluffing. Mortemart was too late; concessions that might have been gladly accepted the day before were now inadequate. But the Orléanists were still a minority, both among Paris as a whole and even among the small circle of elite opposition deputies. A majority of the deputies in Paris still hoped to preserve the Bourbon Restoration in some form. And as for a new republic, it was absolutely thought a possibility — especially among those watching the restive crowds outside the Hôtel de Ville. But Orléanists like Bérard were also greatly playing up the possibility of a republic as a bogeyman, a way to scare ultraroyalists, Bonapartists, and the uncommitted into backing Louis-Philippe, as the lesser of two evils.39

Mortemart, at the end of his energy, walked to the Chamber of Peers. Along the way he saw the city plastered with Thiers’s pamphlet offering up the Duc d’Orléans as king. A doctor present immediately ordered the sickly and pale Duke into a bath for his health. Copies of Charles’s new ordinances were taken to the official government newspaper, the Moniteur, but the editor — the same man who had printed the Four Ordinances a few days before — told them that the municipal commission had dispatched armed men with express orders to stop him from printing any royal decrees. Copies were sent to the Palais Bourbon, where the deputies had reconvened. But Laffitte refused to accept copies of them, on the technical excuse that this was only an informal gathering of deputies, not a formal session. At the Hôtel de Ville Lafayette was even firmer, allegedly declaring: “Charles X, in truth, takes too much trouble in signing these acts; we have ourselves repealed the ordinances during the last three days.” It is possible that even at this late hour, an energetic, forceful prime minister might have been able to rally support for Charles. But the king had not chosen an energetic, forceful prime minister. He had chosen a tired, sick, old man. And events moved on without Charles.40

Lieutenant General of the Kingdom

The center of those moving events was the Chamber of Deputies in the Palais-Bourbon. Ordinarily there were 428 deputies in the Chamber; in the Election of 1830, opposition candidates had won around 274 of those seats, and supporters of Charles and Polignac around around 154. At midday on Friday, July 30, there were 40 or 50 deputies present in the chamber. A single one of them was an ultraroyalist, part of the faction who were loyal to Charles but hostile to Polignac.41 The rest were all opposition liberals. All told there were around 10 percent of the full chamber present, and perhaps 18 percent of the opposition deputies. It was far from a quorum — a perfect excuse to avoid doing something they didn’t want to do, like accept Charles’s new ordinances. But in the heady atmosphere of July 1830, where power was wielded by those who showed up, 50 deputies was plenty enough to do something they did want to do.

And there was something most of the deputies wanted to do: get Charles X away from power. To be clear, this did not mean deposing Charles; some of these deputies would have happily done so, but many more were hesitant. Instead, the idea taking shape among the deputies was to appoint a “Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom.” That’s an old French office dating back to the ancien régime, sort of like a regent or deputy, empowered to rule the kingdom on behalf of an absent or incapable king.

Charles himself had been Lieutenant General of the Kingdom back in 1814, when Napoleon had fallen but Louis XVIII hadn’t yet made it back to France. In this role, Charles negotiated with Allied armies and issued decrees — I talked about that in Episode 26. Now the deputies wanted to use the same office to take power away from Charles. He may not have been literally incapable of ruling, but in the wake of the revolution these deputies considered him practically incapable of ruling.

Appointing a Lieutenant-General was a massive step, but there was a further complication: who to appoint. For example, one obvious choice to replace an incapable king would be the king’s heir. But Charles’s son, the Duc d’Angoulême, might not have changed anything, since Angoulême had been a supporter of the Four Ordinances.42

Instead, this group of opposition deputies rapidly settled on an alternative candidate for Lieutenant-General: Louis-Philippe. The Duc d’Orléans was an obvious choice for those Orléanist deputies who wanted to make Louis-Philippe king, but even more cautious deputies saw the duke as a good candidate to be a de facto regent.

But even if appointing Louis-Philippe to be Lieutenant-General was lower-stakes than crowning him king, it still faced the same key obstacle: no one knew if he would accept.

Which is why it was extremely convenient that about this time, on midday Friday, Adolphe Thiers finally came back to town. Thiers told Laffitte what he had found: that the Duc d’Orléans was still nowhere to be seen, but that Louis-Philippe’s sister Adelaide had offered to personally support the Orléanists’ schemes. That wasn’t the commitment they wanted, but Laffitte decided it was enough.43

What happened next on Friday afternoon was a series of negotiations between the deputies and other groups of influential men in Paris. The 50-or-so deputies at the Palais Bourbon sent a delegation to the Luxembourg Palace, where around 20 or 25 members of the Chamber of Peers were gathered. This was less than 10 percent of the 365 total Peers, but this is July 1830, and we know that doesn’t matter. This small group of Peers — ignoring the protests of their colleague the Duc de Mortemart that this was all illegal — agreed with the Deputies that Louis-Philippe should be offered the lieutenant-generalship.44

More ominously, the deputies received a messenger from Lafayette at the Hôtel de Ville, bearing a warning with an implied threat. The people who had fought and died on the barricades, Lafayette said, would not be satisfied with a mere change in personnel. If the deputies wanted the support of the people, Lafayette’s messenger warned, they would need to make substantive reforms. For men who had first- or second-hand experience with the French Revolution, the prospect of a mob spontaneously attacking the parliament was real and scary. And it would have been hard for them not to have considered another possibility: the distinguished Lafayette appearing on the balcony at the Hôtel de Ville and denouncing the deputies to the assembled people in the square below. For all the power the deputies had assumed to reshape the kingdom, the most powerful man in Paris was still Lafayette, and here he made sure they knew it.45

In response to all of that, Benjamin Constant and Horace Sébastiani drafted an address to Louis-Philippe that tried to thread the needle of all these competing demands. It’s two paragraphs long, and I’ll just read it:

The meeting of the deputies at present in Paris begs to His Royal Highness Monseigneur the Duc d’Orléans to come to the capital to exercise the functions of lieutenant-general of the kingdom, and expresses to him the wish to retain the national flag.

The deputies have been concerned, moreover, with assuring to France in the next session of the Chambers, all the indispensable guarantees for the full and complete execution of the Charter.46

The deputies assert their own authority, officially offer Louis-Philippe the lieutenant-generalship, and mention the one reform that everyone agreed on: replacing the white Bourbon flag with the revolutionary tricolor. Beyond that, they suggested the need for more reform without actually making any promises, and avoided any mention of Louis-Philippe possibly becoming king.

This carefully worded dispatch was then sent off to the duke’s chateau of Neuilly, accompanied by a delegation of 12 deputies, to formally present it. And finally, Louis-Philippe was there in person to receive it. Adelaide had sent word to her brother that it was time to leave hiding. In the words of Louis-Philippe’s biographer Munro Price, “it would not do for him to be absent a second time.” Outside, after dark, under flickering torches, the Duc d’Orléans met the delegation, told them he would accept the office of Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, and set out for Paris.47

The General Will

The Orléanists were perhaps the strongest faction making a play for power as Thursday turned into Friday, with their control over the formal power center that was the French parliament. But there were other sources of power in Paris on these heady days, and other factions vying for control. With little support among the deputies, the Bonapartists and republicans set out to make direct appeals to the people. As the contemporary historian Louis Blanc put it, describing a group of republicans: “position, reputation, great fortunes, all these things they [lacked]: this was their weakness, but it was also their strength. Inasmuch as they could brave everything, they could obtain everything… they took but little account of obstacles.”48

The particular republican meeting Blanc describes took place on Friday, and could be charitably described as feisty. Men gave speeches with guns in hand, and one orator who tried to advocate for Louis-Philippe had those guns leveled at him. While some of the details of the plotting were not yet public, everyone at this point knew where was a serious effort underway to put Louis-Philippe on the throne of France. The entire city had been blanketed overnight with copies of Adolphe Thiers’s manifesto, declaring that “The Duc d’Orléans is a prince devoted to the cause of the Revolution” and that “It is from the French people that he will hold his crown.” For these musket-toting republicans, replacing Charles X with his cousin was no solution at all, and worse, threatened to squander the revolutionary moment when greater things seemed possible. Eventually, and without shooting any speakers, this meeting of republicans sent a messenger to visit Lafayette at the Hôtel de Ville with a simple message: pump the brakes. “Means must be taken,” the messenger’s dispatch said, “to prevent any proclamation from being made which designates a chief, when the very form of the government cannot be determined.” These men saw what the Orléanists were trying to do by naming Louis-Philippe the Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, and wanted to prevent it.49

Below: Charles de Rémusat, 1843, by Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But Lafayette, for all his republican sympathies, was not especially helpful. Blanc, a republican himself, suggests that Lafayette lacked “hardihood” and wasted the activists’ time by telling a meandering story before refusing to commit to anything. But other sources suggest a different explanation: by this time, Lafayette was coming around to the Orléanist camp. The Orléanist Charles de Rémusat reports that he visited Lafayette — his wife’s grandfather — on Friday morning to sound out his intentions, telling his grandfather-in-law that given the circumstances, the only choices to lead France were Louis-Philippe or himself. Lafayette supposedly replied that “the Duc d’Orléans will be king, as sure as I shall not be.” Later, Lafayette wrote that he thought most French people in 1830 did not want a republic. “The first condition of republican principles being to respect the general will,” Lafayette wrote, “I prevented myself from proposing a purely American constitution — in my opinion the best of all. To do so would have been to disregard the wish of the majority, to risk civil troubles, and to kindle foreign war.” Word slowly filtered back to Orléanists that Lafayette might be on their side. Though as we’ll see, if Lafayette could be considered an Orléanist, he was part of the left-wing group of Orléanists who wanted more radical reforms to the Charter, not the conservatives hoping to keep things the same.50

But Lafayette, for all his republican sympathies, was not especially helpful. Blanc, a republican himself, suggests that Lafayette lacked “hardihood” and wasted the activists’ time by telling a meandering story before refusing to commit to anything. But other sources suggest a different explanation: by this time, Lafayette was coming around to the Orléanist camp. The Orléanist Charles de Rémusat reports that he visited Lafayette — his wife’s grandfather — on Friday morning to sound out his intentions, telling his grandfather-in-law that given the circumstances, the only choices to lead France were Louis-Philippe or himself. Lafayette supposedly replied that “the Duc d’Orléans will be king, as sure as I shall not be.” Later, Lafayette wrote that he thought most French people in 1830 did not want a republic. “The first condition of republican principles being to respect the general will,” Lafayette wrote, “I prevented myself from proposing a purely American constitution — in my opinion the best of all. To do so would have been to disregard the wish of the majority, to risk civil troubles, and to kindle foreign war.” Word slowly filtered back to Orléanists that Lafayette might be on their side. Though as we’ll see, if Lafayette could be considered an Orléanist, he was part of the left-wing group of Orléanists who wanted more radical reforms to the Charter, not the conservatives hoping to keep things the same.50

As you can see, sorting out Lafayette’s attitudes to the republicans during these days is complicated. His attitudes to the Bonapartist camp are much more straightforward. The Bonapartists made their move on Friday, when a journalist named Evariste Dumoulin wrote a proclamation declaring Napoleon II to be emperor of France, and showed up at the Hôtel de Ville to drum up support. Dumoulin thought he was making some progress when word arrived that Lafayette wanted to meet with him. Dumoulin was escorted through the halls of the Hôtel de Ville to a small waiting room, and was told Lafayette would be with him shortly. When Lafayette was not there shortly, Dumoulin opened the door to find two National Guardsmen blocking his way. He had been tricked, and would remain trapped in this small room until 7 p.m., by which time events had moved on.51

The retreat

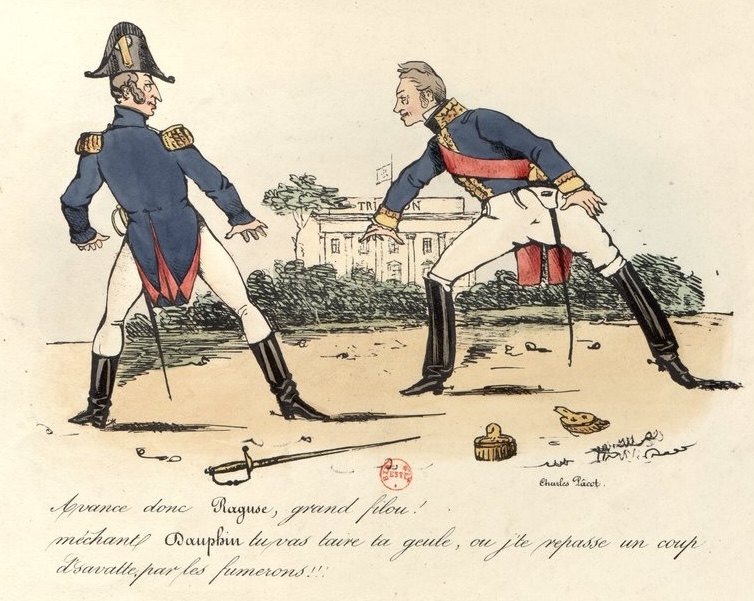

Back in Saint-Cloud, things were not going well. The remains of Marmont’s army had fallen back to this royal palace in considerable disarray; on their retreat, they had been attacked by citizens of the towns they passed through. The statesman Chateaubriand, in his memoirs, contrasts Marmont’s battle-weary army with the “titled, gilded, and well-fed flunkeys who dined at the royal table.” Marmont himself had an explosive confrontation with the most titled and gilded of them all — the king’s son, the Duc d’Angoulême. Trying to take a leading role in his father’s disintegrating reign, Angoulême summoned Marmont and angrily confronted him — calling the marshal a traitor and trying to physically take Marmont’s sword from him. Marmont resisted — writing in his memoirs that he said Angoulême “could snatch it from me, but I shall never hand it to you”; Chateaubriand claims Angoulême cut his hand trying to grab the sword. With tempers running high, guards were summoned, and Marmont was placed under arrest. Angoulême took personal command of the remains of the royal army.52

“Come on Ragusa, you great rogue!” “Nasty Dauphin, shut up or I’ll give your skinny legs another kick.” A loose translation of this 1830 caricature by Charles Pâcot. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The change in command did nothing to solve the primary danger still menacing Charles’s army: low morale. Reports of new mutinies and defections arrived almost by the hour — first small groups, then larger and larger units. A Swiss battalion surrendered to armed townsfolk during the day Friday. The 50th Line regiment surrendered that evening. Even companies of the Royal Guards were starting to waver, with colonels telling Angoulême that they could not guarantee their men would remain loyal. Meanwhile news arrived of rising unrest in the towns and villages surrounding Saint-Cloud. Marmont, who the king had released, urged Charles to retreat while he still had an army. But as always, Charles hated to back down any more than he had to, and instead waited all day in the hopes that Mortemart would negotiate an end to the fighting.53

At this point, this was a foolish hope, and reality sunk in Friday night. In the early hours of Saturday morning, Charles left Saint-Cloud for the palace of Versailles, which was slightly further from Paris. There he re-united with his ex-ministers, some of whom now advised him to flee to the countryside and raise the banner of resistance in the western city of Tours. But Charles ultimately concluded his former ministers were now liabilities. Each was given 6,000 francs and a passport out of the country, and told it was every man for himself. The king and his dwindling court retreated further themselves, to the royal hunting retreat at Rambouillet. That’s the same hunting area, 44 kilometers or 27 miles southwest of Paris, where Charles and Angoulême had gone to hunt on Monday, July 26, bagging game as Paris grappled with the newly announced Four Ordinances. Just five days later, it was Charles who had become the hunted prey.54

Some of the advisors still around Charles continued to counsel resistance. But the old king didn’t have the heart for it any more. On Sunday, August 1, 1830, one week after he had issued the Four Ordinances, Charles gave up on military resistance and gambled everything on family: He appointed his cousin Louis-Philippe as Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom.

This was, of course, the exact office that the deputies had appointed Louis-Philippe to. But there was a difference between acting as regent on behalf of a revolutionary assembly, and acting as a regent on behalf of the king himself. Charles had always had a warm personal relationship with Louis-Philippe, and hoped that these bonds of family and friendship might persuade the duke to uphold the rights of the Bourbon dynasty. In his proclamation, Charles said he was “counting on the sincere attachment of my cousin, the Duc d’Orléans.”55

Just how sincere was that attachment? Louis-Philippe gave some signals in these crucial days that suggested it was genuine. Crucially, on Saturday, July 31, Louis-Philippe met with Mortemart. It was shortly after 4 a.m. when the two met, and Louis-Philippe had had barely any sleep — he had only reached the city around midnight. Mortemart found Orléans in an extremely casual state — “wigless, sweating, his shirt undone, with a Madras handkerchief tied around his head.” And as Mortemart related the meeting, Louis-Philippe was emotional and apologetic — swearing that “he had come to Paris only because the revolutionaries had compelled him to” and asserting that “he would ‘rather be torn in pieces’ than accept the crown.” After this profession, Louis-Philippe gave Mortemart a letter for Charles asserting his loyalty. A few hours later, when a group of deputies came to meet with him, the man who had accepted the lieutenant-generalcy just the night before was now suddenly uncertain. He had “ties of family and duty” and told the incredulous deputies that didn’t see any need to move quickly.56

The Sphinx of Orléans

Is this the real Louis-Philippe, loyal to his cousin and compelled against his will to take power? It’s not impossible. This was a time when bold men could wield power simply by showing up and claiming it, and Louis-Philippe had spent days avoiding the best efforts of his friends to put him in power. Plenty of other centrist French political figures had clung to vestigial loyalty to the Bourbon dynasty until awkwardly late into the revolution — could not Louis-Philippe have been among them?

Is this the real Louis-Philippe, loyal to his cousin and compelled against his will to take power? It’s not impossible. This was a time when bold men could wield power simply by showing up and claiming it, and Louis-Philippe had spent days avoiding the best efforts of his friends to put him in power. Plenty of other centrist French political figures had clung to vestigial loyalty to the Bourbon dynasty until awkwardly late into the revolution — could not Louis-Philippe have been among them?

Right: Unknown artist, “Portrait of Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans,” before 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Moreover, it’s helpful here to remember a formative moment in Louis-Philippe’s own life, one I covered way back in Episode 13. Louis-Philippe’s father, Philippe, had infamously betrayed the Bourbons during the French Revolution. As a member of the revolutionary National Assembly, Philippe had voted to execute King Louis XVI, Charles’s oldest brother. Louis-Philippe, a young man at the time, saw his personal reputation ruined by his father’s actions; he was effectively expelled from the broader Bourbon family, and eventually had to come crawling on bended knee to get forgiveness. It was, in fact, Charles who had vouched for Louis-Philippe and helped convince Louis XVIII to formally forgive him.57 It’s not hard to believe this memory might have caused Louis-Philippe to hesitate when faced with his own chance to betray his Bourbon cousins.

I call this the Loyal and Reluctant Theory — that Louis-Philippe didn’t want any of this, and got pressured into it. But there are several other interpretations of Louis-Philippe’s enigmatic actions in these days that we should consider. One of them, advanced by Charles’s supporters, we might call the Ambitious Plotter Theory. This sees episodes like the one with Mortemart as an elaborate charade. Far from being loyal to Charles, this theory goes, Louis-Philippe was making an active play for the throne, one he concealed behind a genial mask even as he manipulated events. This Ambitious Plotter version of Louis-Philippe wanted to take power, but to look like he was only reluctantly having power forced on him.

Was it true? Again, it’s possible. We know Louis-Philippe was an ambitious man and that he had wanted to be king in the past. If someone has the means, motive, and opportunity to make something happen, and then that thing happens, doesn’t that mean it’s fair to conclude they made it happen? As the ancient Romans said, cui bono — who benefits? On July 31, 1830, the man benefitting was Louis-Philippe, being offered at the very least de facto rule of France. So it seems reasonable to suspect Louis-Philippe of being less innocent than he made out. On the other hand, while this principle is sometimes a good way to identify the culprit behind an action, it’s certainly not true that crimes are always committed by the person who stood to benefit the most. But if you look at what Louis-Philippe did and not what he said, the Ambitious Plotter theory makes some sense. One might note that the professions of loyalty in the letter Louis-Philippe wrote for Charles were vague and general — and that he asked Mortemart to return the letter to him after showing it to Charles.58

The third interpretation to consider is one I call the Terminally Indecisive Theory. This explains these contradictions and ambiguities by alleging that Louis-Philippe was neither actively loyal nor actively conniving — but simply afraid to put his neck out. Back in 1825, the duke’s architect had written in an otherwise positive description that Louis-Philippe was “immense in small matters,” but “distracted, indecisive, and almost always mediocre in important ones.”59 When Louis-Philippe did take action, what he did tended to reflect who was advising him. So on Friday evening, he was being advised by the fiery Adelaide to accept the lieutenant-generalship, and did so. On Saturday morning, he was being beseeched by Mortemart to be loyal to Charles, and insisted that he was. When the entreaties were less firm, Louis-Philippe temporized and stalled.

The truth probably encompasses all three theories. People are complicated, and the historical record suggests that Louis-Philippe was loyal, and also ambitious, and also indecisive. These three traits were clashing inside him in these heady days after the Four Ordinances.

“He should accept”

But Louis-Philippe couldn’t temporize forever, and most of the people around him were advising him to move toward power. Perhaps decisively, the duke sent a message Saturday morning to the famous statesman Talleyrand, asking the diplomat what he should do about the offer of the lieutenant-generalship. Talleyrand, who always had a gift for memorable phrasing, replied concisely: “He should accept.” And Louis-Philippe did.60

But Louis-Philippe couldn’t temporize forever, and most of the people around him were advising him to move toward power. Perhaps decisively, the duke sent a message Saturday morning to the famous statesman Talleyrand, asking the diplomat what he should do about the offer of the lieutenant-generalship. Talleyrand, who always had a gift for memorable phrasing, replied concisely: “He should accept.” And Louis-Philippe did.60

Left: Ary Scheffer, “Portrait of the Prince de Talleyrand,” 1828. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

With the Duc d’Orléans fully on board at last, the liberal deputies moved quickly to formalize the appointment. Louis-Philippe worked with two close advisors, Horace Sébastiani and André Dupin, to draft a formal acceptance of the lieutenant-generalcy, in which he declared that he endorsed the tricolor flag, that parliament would meet soon, and that “a charter would henceforth be a reality.” In other words, Louis-Philippe was promising something close to the status quo with some reforms — a constitutional monarchy, freed from the threat of Ultraroyalist plotting, but not a republic or a Bonapartist empire. Just who the constitutional monarch would be remained — for the moment — unstated. Regardless, the duke’s declaration was applauded by the rapidly growing number of deputies in Paris — with new arrivals, their numbers had almost doubled overnight, from 50 to 95.61

But if the deputies cheered Louis-Philippe’s decision to accept the lieutenant-generalcy, many details remained undecided. Some of the more conservative opposition deputies were hoping to change the status quo as little as possible, but they were opposed by more radical deputies who wanted bigger changes. These radicals now flexed their muscles and forced the deputies to endorse specific reforms in their reply to Louis-Philippe’s declaration, including re-establishing the National Guard and giving journalists the right to a trial by jury if accused of libel or other press offenses. With these promises in hand, 95 deputies paraded over to formally present them to Louis-Philippe, led by a gout-stricken Jacques Laffitte in a sedan chair.62

The republican kiss

All this was well and good, but as we know, the deputies were far from the only power in Paris. There was still Lafayette and the commissioners at the Hôtel de Ville, surrounded by a rowdy, pro-republican crowd. Any leader picked by deputies needed Lafayette and the people of Paris on board, or the anti-Bourbon revolt of the past few days could spiral into a wider civil war.63

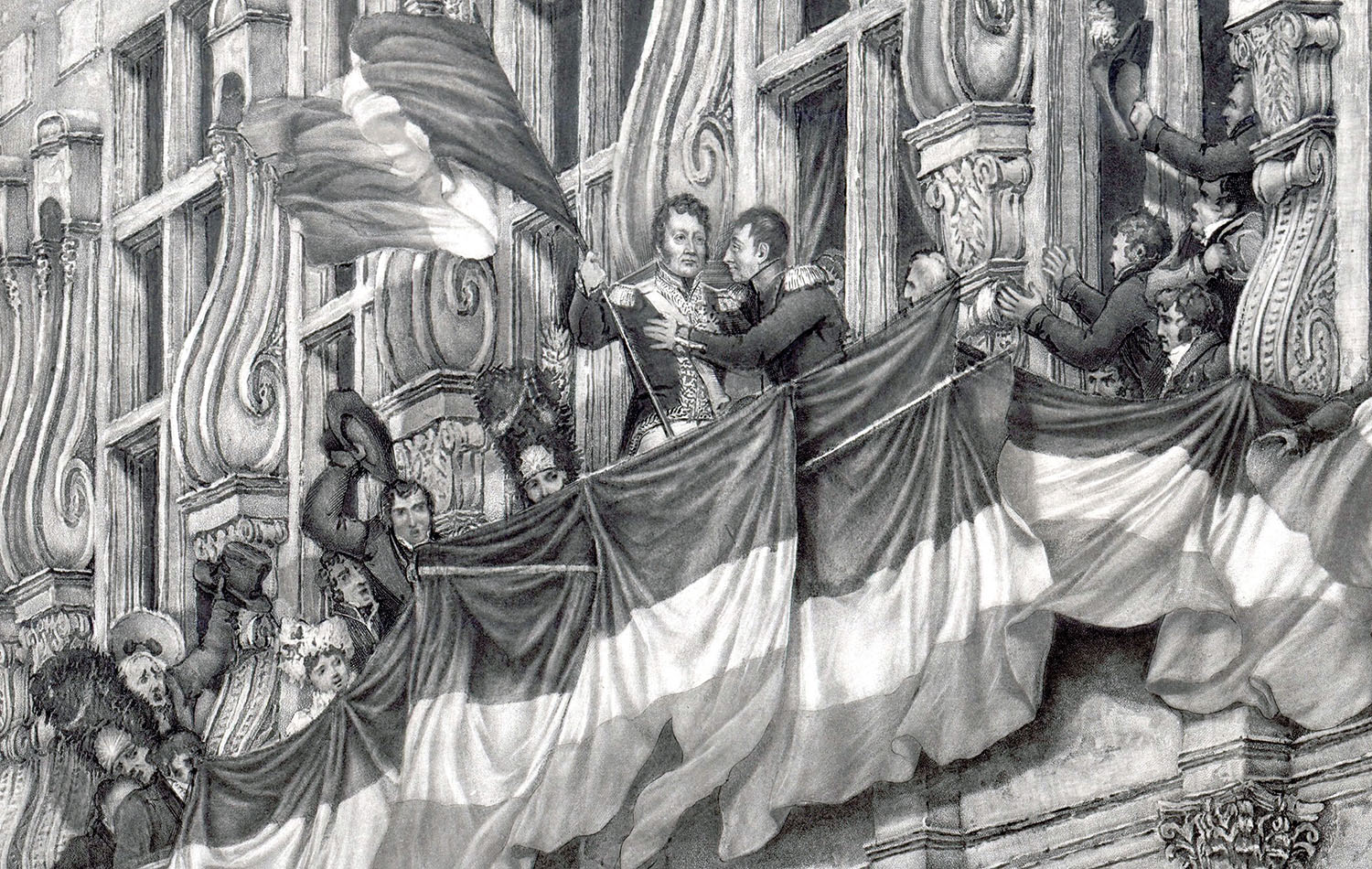

So here, indecisive or not, Louis-Philippe did something brave: he climbed on a horse and rode toward the Hôtel de Ville. It was around 2 p.m. on Saturday, July 31, 1830. The duke was followed by the procession of deputies, but not by any guards. The streets of Paris were still crowded, and these crowds grew more and more hostile as he neared the city hall. Some men — though certainly not all — chanted “Down with the Duc d’Orléans” and “Down with the Bourbons,” which everyone knew was intended to apply to Charles’s Orléanist cousin, too. Historian David Pinkney notes that “a single ball fired from a musket easily concealed in an overlooking window or from a bystander’s pistol could have easily ended the life of the Duke and the hopes of his supporters, but he rode forward with remarkable courage and coolness.” Louis-Philippe and the deputies made it through the crowd unharmed into the Hôtel de Ville, but their reception didn’t improve when they stepped in. The building was filled with throngs of men of all sorts, including “republicans who made little effort to conceal their hostility.”64

Charles-Philippe Larivière, “The Arrival of the Duke of Orleans at the Hôtel de Ville,” 1836. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the midst of all this, Lafayette remained calm and polite. He met Louis-Philippe on the steps and escorted him in, where a deputy read out their proclamation, the one appointing the Duc d’Orléans as lieutenant-general, and promising a host of new liberties like jury trials for press offenses.65 These promised liberties drew cheers from the crowd inside the Hôtel de Ville, and then Louis-Philippe stepped forward and promised to respect these liberties as leader. Lafayette was convinced, and walked up to shake Louis-Philippe’s hand.66 Easy-peasy!

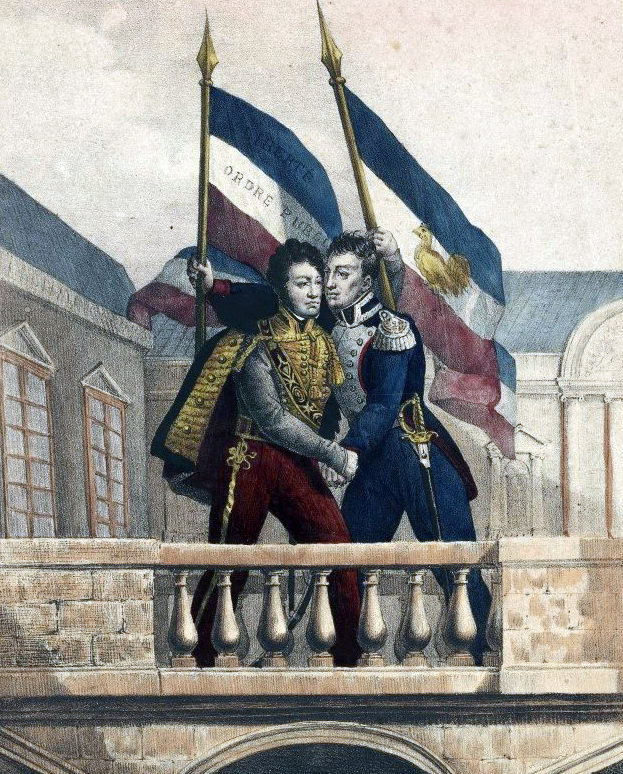

Except that this handshake took place behind closed doors. Through the windows, the restive crowd in the plaza outside could still be heard, including chants of “Down with the Duc d’Orléans” and “Long live the Republic.” But Lafayette, that old veteran of 1789, had a “genius” for grand popular gestures. Forty-one years earlier, a much younger Lafayette had faced down a French crowd calling for Marie-Antoinette’s head; he brought her out onto a balcony and dramatically kissed her hand, defusing the mob — for a while, anyway — with this symbolic endorsement. Now, with Lafayette at the center of yet another French revolution, he repeated the trick. The general and the duke appeared together on the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, along with a large tricolor flag. The crowd chanted “Long live Lafayette,” but nothing about Louis-Philippe. So Lafayette embraced Louis-Philippe, giving him a kiss on the balcony that was both physical and highly symbolic — a “republican kiss,” as Chateaubriand called it, that conferred Lafayette’s revolutionary credentials on the suspiciously Bourbon Duc d’Orléans. And it worked: the crowd erupted into cheers, not just “Long live Lafayette” but also, at last, “Long live the Duc d’Orléans.”67

Except that this handshake took place behind closed doors. Through the windows, the restive crowd in the plaza outside could still be heard, including chants of “Down with the Duc d’Orléans” and “Long live the Republic.” But Lafayette, that old veteran of 1789, had a “genius” for grand popular gestures. Forty-one years earlier, a much younger Lafayette had faced down a French crowd calling for Marie-Antoinette’s head; he brought her out onto a balcony and dramatically kissed her hand, defusing the mob — for a while, anyway — with this symbolic endorsement. Now, with Lafayette at the center of yet another French revolution, he repeated the trick. The general and the duke appeared together on the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, along with a large tricolor flag. The crowd chanted “Long live Lafayette,” but nothing about Louis-Philippe. So Lafayette embraced Louis-Philippe, giving him a kiss on the balcony that was both physical and highly symbolic — a “republican kiss,” as Chateaubriand called it, that conferred Lafayette’s revolutionary credentials on the suspiciously Bourbon Duc d’Orléans. And it worked: the crowd erupted into cheers, not just “Long live Lafayette” but also, at last, “Long live the Duc d’Orléans.”67

Kiss from a duke on the quai

But let’s hold up for a second and rewind to that kiss. Because when I, as a 21st Century American, first read about this time when the Marquis de Lafayette kissed the Duc d’Orléans and it ended a revolution, I definitely thought, “Huh, that’s a little weird.” Unfortunately, I cannot tell you exactly how Lafayette kissed Louis-Philippe, but it is regularly described as “dramatic.” The incident has been widely depicted in art, in which the two men have been shown doing everything from chastely holding hands to leaning in face-to-face. You can see some of this artwork alongside a full annotated transcript of this episode at thesiecle.com/episode45.

Above: Detail from Ambroise Louis Garneray, “The Duc d’Orléans Is Presented to the People by the General Lafayette on the Balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, July 31, 1830,” after 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Whether it was on the lips or otherwise, though, a public kiss like this wasn’t that unusual for 1830 France. During the Middle Ages, kissing on the lips between non-lovers had been common, as a gesture of affection, peace, respect, or friendship. The custom had declined over time, and had become relatively uncommon by the 19th Century, but it was far from extinct.68

We can see this from several notable examples from 1792, on both sides of the French Revolution. While France was facing foreign invasion that year, a member of the revolutionary National Assembly named Lamourette issued a heartfelt plea for deputies to set aside their partisan divides in favor of national unity. “The deputies at once fell into each other’s arms, and in a universal kiss of reconciliation every one forgave each other’s wrongs.” A few months later, when the attorney Malesherbes volunteered for the perilous job of defending King Louis XVI from treason charges in front of the revolutionary National Convention, Louis showed his gratitude by standing up and kissing Malesherbes. The fact that Louis XVI, Malesherbes, and Lamourette all ended up dying to the guillotine should not distract us from the conclusion that for men like Lafayette (born 1757) and Louis-Philippe (born 1773), spontaneous public kissing between colleagues was an accepted practice during moments of high emotion.69

*Above: Anonymous sculptor, “Meeting Between Louis-Philippe and Lafayette at the Hôtel de Ville, July 31, 1830,” after 1830. Public domain via Musée Carnavalet.

A monarchy surrounded

The next day, Lafayette gave Louis-Philippe another gift besides his kiss. He gave him a slogan. After Louis-Philippe had visited the heart of popular power at the Hôtel de Ville, Lafayette returned the favor by visiting the duke at his own base of power, the Palais-Royal. Lafayette was accompanied by the members of the Municipal Commission, who now donned formal sashes of office in the colors of the revolutionary tricolor. Here, Lafayette tried to press Louis-Philippe to govern in a more progressive way — not as a republic, but perhaps as something close.

Lafayette told the duke that “I am a republican,” and that “I regard the constitution of the United States as the most perfect that ever existed.” Louis-Philippe, who had lived in exile in the U.S. for two years in the 1790s, told Lafayette that he agreed! But, the duke asked, “do you believe that in France’s situation, in the present state of opinion, it would be proper for us to adopt that constitution?” The old revolutionary said no. “What the French people must have today,” Lafayette said, “is a popular monarchy surrounded by republican institutions.”70