Episode 46: Revolutions

This is The Siècle, Episode 46: Revolutions.

Welcome back, everyone! Last time, I wrapped up my series on France’s July Revolution of 1830, when King Charles X launched a coup against the liberal opposition and ended up losing his throne.

Today, I could think of no better way to follow that up than a discussion with one of the world’s preeminent experts in 19th Century revolutions: pioneering history podcaster Mike Duncan. Many of you are probably familiar with Mike, but if you’re not, know that his podcasts were the single most formative influence on The Siècle.

Today, I could think of no better way to follow that up than a discussion with one of the world’s preeminent experts in 19th Century revolutions: pioneering history podcaster Mike Duncan. Many of you are probably familiar with Mike, but if you’re not, know that his podcasts were the single most formative influence on The Siècle.

If you’re new here, welcome! The Siècle is a serialized narrative history podcast telling the story of France’s overlooked century in between the fall of Napoleon and the First World War. I’ve just spent 45 episodes covering the Bourbon Restoration, from its beginnings in 1814 through to its collapse in the July Revolution. Fans of Mike Duncan’s Revolutions will probably find a lot to like here! I recommend you start with Episode 1, to hear the story from the beginning. Alternatively, if you just want to get a sense of what a typical episode of the show is like, check out Episode 36 — a standalone episode that will give you a good idea of the show’s research and storytelling.

You can find out more about how to subscribe to The Siècle at thesiecle.com/start. That’s t-h-e-s-i-e-c-l-e dot com slash start. You can also visit thesiecle.com/episode46 for a full transcript of this interview.

Finally, you can visit patreon.com/thesiecle, where all patrons pledging as little as $1 per month get ad-free feeds of the show. All these links are in the show notes.

Now, without further ado, here’s Mike Duncan:

THE SIÈCLE: Mike Duncan, welcome to The Siècle.

MIKE DUNCAN: Thank you very much for having me.

SIÈCLE: I’m guessing that a lot of you listeners are already very familiar with Mike Duncan. But if you’re not — I’d call him history podcast royalty, but given what we’re talking about today that might not actually be a compliment.

DUNCAN: David, David. I’m merely the First Citizen.

SIÈCLE: (Laughs) Mike is the host of the Revolutions podcast, which has covered historical revolutions from the English Civil War through the Russian Revolution, into space, and more to come and we’ll talk about that in a little bit. Why don’t you introduce yourself to anyone who doesn’t know your background? Talk about how you got interested in revolutions in the first place, as well as other projects you have.

DUNCAN: Hi, I’m Mike Duncan. I have been podcasting about history for a very long time now. I started the The History of Rome podcast way back in July of 2007, and have been pretty much podcasting ever since then. I’m going to be coming up on the 20th anniversary of the History of Rome like, very fast, which is kind of insane.

But after The History of Rome, I moved into doing the show Revolutions, which each season covers a great political revolution in history. And this really goes back to revolutions and revolutionary events being one of my first historical loves back when I was really getting into things as a teenager, I was really into the American Revolution and I was really into the Russian Revolution because I’m old enough to have been like… I lived through the Cold War and I was sort of coming out of the Cold War, and so those revolutionary events that sort of got the United States started and the Soviet Union started were always really interesting to me.

And then, as the years went by, I just sort of continued to study it and learn about it, and when The History of Rome ended, the funny thing is that I wanted to next do a series that would be a little bit shorter and a little bit more compact. And I meant to do the Revolutions podcast for like three years, and every season would be like twelve to fifteen episodes, and then that all went to hell when I decided I could not cover the French Revolution in 15 episodes. That would be insane. And so, that got me going on the version of the Revolutions podcast which lasted for nine years before I took a break and is now restarted and will be ongoing for a very long time. So far as I can tell.

SIÈCLE: Yeah, I think we’ll talk about the future plans for Revolutions at the end of this discussion here, but in particular, I’ve invited you onto The Siècle because the narrative of The Siècle just finished with the July Revolution, or at least the exciting part of the July Revolution, when a revolution ends is a much bigger topic that may come up later. And you have not only covered the July Revolution yourself on Season Six, I believe, of Revolutions — but you also have uncovered all sorts of different revolutions in France and other countries in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, I think are uniquely situated to help put some of what listeners of The Siècle have learned about the July Revolution into a broader context.

DUNCAN: Yeah.

SIÈCLE: Just to start before we get into more detail, what stands out to you about the July Revolution among all the revolutions you cover? What makes this unique or interesting?

DUNCAN: Well, you know, coming out of the — okay, so the Revolution of 1830 is sort of after the first wave of the great revolutions. And really like, the Age of Revolution and the Age of Atlantic Revolution, which kind of covers the American Revolution and the French Revolution, Spanish American independence, like all that stuff is sort of winding down when the Revolution of 1830 comes along. And the Revolution of 1830, to me, feels like a real pivot point between the kinds of revolutions that were going on in the later 18th Century and early 19th Century and the kind of revolutions we would be looking forward to in the 19th Century.

Because, by the time we get to 1848, which is, you know, just a scant 18 years after 1830, that’s when we really start getting into, like, labor being involved in things. And Marx is on the scene. And we’re starting to get like, real sort of the social revolutions that are going to be the engine of revolution going forward, and 1830 sort of exists in-between those two, right? It’s after the great liberal revolutions, and before the social revolutions. And so that’s kind of like, as an ideological point, you know, that is interesting to me.

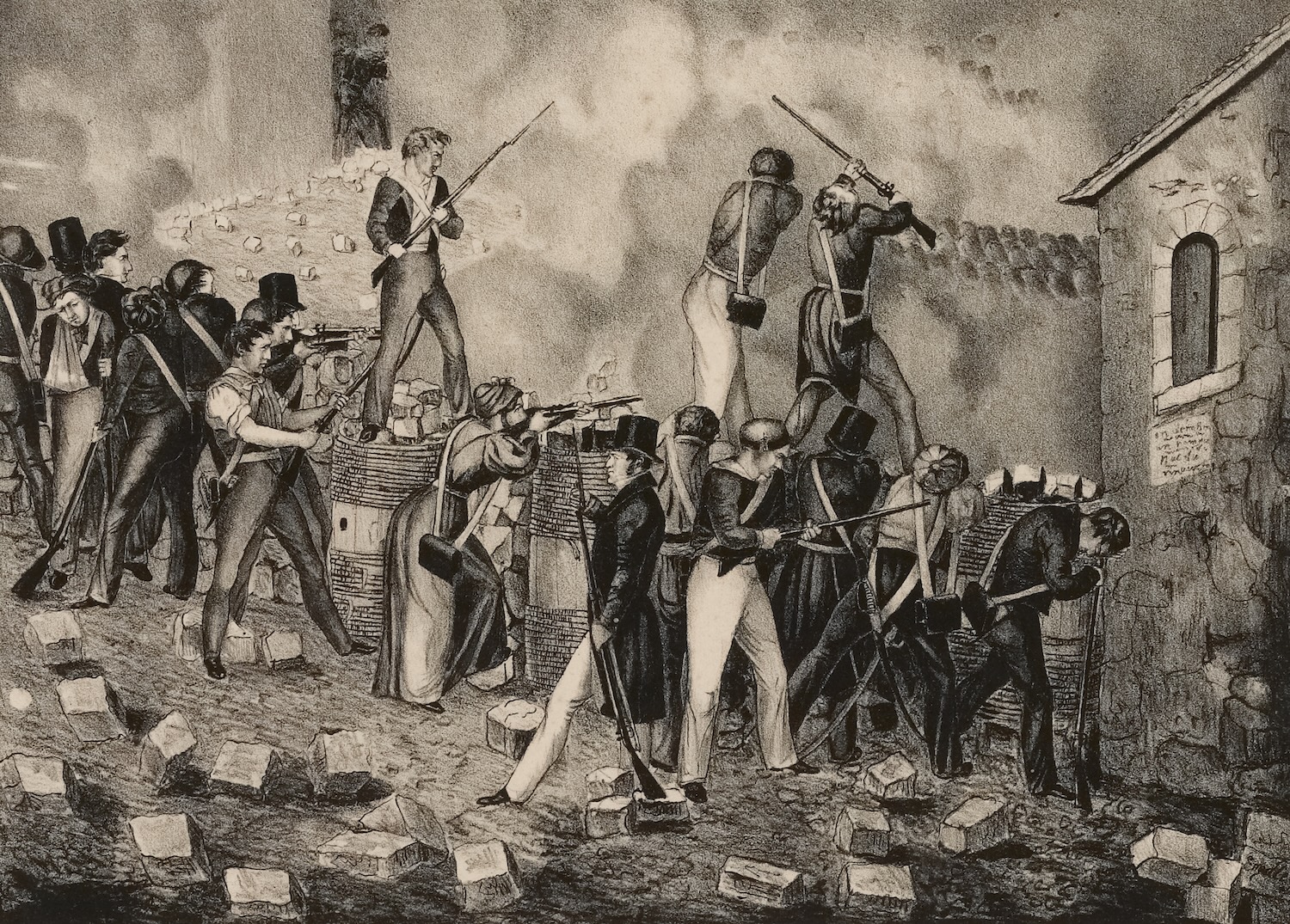

Right: Fighting at a barricade near the Hôtel de Ville. Unknown artist, circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And then, the other bit of it is sort of how the revolution actually unfolded, because 1830 is when we really start getting into barricade fighting in the streets, and sort of like, rapid-fire insurrectionary events in the streets of Paris. And of course, things had happened — you know, there were lots of street actions during the French Revolution, and there were barricades that had been put up in Saint-Antoine during the middle stages of the French Revolution. But this sort of, like, the iconic imagery of the Parisians at the barricades really comes to us initially from 1830, right? And Liberty Leading the People — like that famous painting is from the Revolution of 1830, which most people completely miss; they all think it’s just from the French Revolution. So those two kinds of things: the mode that the revolution took, and its ideological meaning in the larger scope of revolutions makes it — like, the July Revolution is obscure, but it’s also like it’s fascinating and important in its own right.

Below: Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty Leading the People,” 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

SIÈCLE: It feels like a sort of — not just with the barricades, but in other elements — the revolution sets a sort of template that a lot of revolutions for the rest of the 19th Century are imitating or trying to differ themselves from in varying ways.

DUNCAN: Yeah, exactly. And the social revolutionaries that come later are often trying to repudiate what had happened in 1830, which they thought 1830 was the victory, not of progressive forces of revolution, but of these conservative liberals that wanted to arrest the social revolution they wanted. So, for them, they would look to 1832 as sort of the failed attempt at a second revolutionary wave that would have been the equivalent of 1793 and 1792 in the original French Revolution.

And then later liberals are going to be looking at that and saying, no, that’s all we want. Like, that’s the extent of what we want out of a revolution. We don’t want this social revolutionary stuff. So some people were looking back on 1830 and saying, “Yeah, that’s the model,” and other people were looking back on 1830 and said that was a job clearly half-done.

SIÈCLE: Well, looking at any revolution, perhaps the place you have to start is what people are revolting against. Charles X of France is a very interesting character, I’ve found, certainly, and I think you might agree as well. What stands out about Charles as a monarch — a target of a revolution — for you, and how does he differ compared to other revolutions you’ve covered and who people were revolting against?

SIÈCLE: Well, looking at any revolution, perhaps the place you have to start is what people are revolting against. Charles X of France is a very interesting character, I’ve found, certainly, and I think you might agree as well. What stands out about Charles as a monarch — a target of a revolution — for you, and how does he differ compared to other revolutions you’ve covered and who people were revolting against?

DUNCAN: Charles X of France is one of our emblematic great idiots of history. One of the theses that has emerged from the Revolutions podcast — I didn’t intend this going into it, it kept emerging over and over again — is that revolutions are not waged against competent administrations and people who are doing a good job. They are rarely even against just a regime that is tyrannical and exploitive and abusive of people because often those tyrannical and exploitive and abusive regimes are very good at doing those things and so they keep revolution at bay.

Right: Workshop of François Gérard, “Portrait of Charles X. King of France, in coronation robes.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But Charles X comes into a situation where conservatism — this is like the Age of Metternich, right? — conservatism kind of was the prevailing norm across Europe in the post-Napoleonic era. And even though there were nods to liberalism — there’s a Charter of Government and there’s a Chamber of Deputies and all of that stuff — it’s really quite conservative. And if Charles had just done nothing and just sort of let events play out, he would have been fine. He would have been fine. The monarchy would have stayed in place. The Bourbons would have stayed as the royal family of France.

But instead, he comes in and immediately starts trying to drive everything back to like 1788. He wants to undo everything. He’s been pissed off about the Revolution since 1789, and yeah, I agree. Charles — who was, once upon a time, the Comte d’Artois — is a fascinating figure. Right? He was the very first emigrant out of the French Revolution. He split the scene in July of 1789 and he wasn’t reconciled to anything that had happened since then. And even though there are practical things that he couldn’t undo — he couldn’t re-seize those nationalized lands that had been sold off after those properties were seized by the revolutionaries, and so he couldn’t necessarily give people their property back, but he definitely wanted to use state taxpayer funds to reimburse all the old nobility for their lost property.

And then he just starts coming hard at these basic victories of the revolutionary era. Something resembling freedom of the press, something resembling freedom of speech, something resembling participatory government — those things existed, but in [minimal] ways. There wasn’t actually just blanket freedom of the press or blanket free speech, and the electorate for the Chamber of Deputies was very small. But he didn’t even — he couldn’t even deal with that.

Below: Samuel Morse, “Portrait of La Fayette,” 1826. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

So he just starts driving a political crisis against him where, when he comes into office, the liberals, the French liberals, are really, really, really on the back foot. I mean, Lafayette went back to do his grand tour of the United States in 1824 and 1825 partly because he was so kind of despondent about the state of liberalism in Europe. You know, he had just watched the French army go in and conquer the liberal regime in Spain, and rather than that triggering a mutiny or uprising in France, the French just kind of went along with it, so he was like, “God, we’re never getting anywhere.”

So he just starts driving a political crisis against him where, when he comes into office, the liberals, the French liberals, are really, really, really on the back foot. I mean, Lafayette went back to do his grand tour of the United States in 1824 and 1825 partly because he was so kind of despondent about the state of liberalism in Europe. You know, he had just watched the French army go in and conquer the liberal regime in Spain, and rather than that triggering a mutiny or uprising in France, the French just kind of went along with it, so he was like, “God, we’re never getting anywhere.”

SIÈCLE: Plus, the failure of the Carbonari revolutions, as well, that he was part of.

DUNCAN: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, the failure of all those Carbonari revolts. Yeah, and so he — he’s despondent. And this is 1824, there’s just six years before there’s a full-blown liberal revolution against Charles X. And I don’t think that revolution happens without Charles X being, like, a huge idiot about the things that he was doing.

SIÈCLE: One of the things that struck me about Charles in all this was, as you said, that had he just done nothing he would have continued. But Charles very clearly didn’t think that doing nothing was an option. He saw the relatively moderate gains of the liberals — the French liberals at the time — and thought it was unacceptable, based on his memory of the French Revolution. He remembered his brother being forced to fire his prime minister and thought that that sign of weakness was what kicked everything off. He was determined not to make that same mistake, but he saw even demands for relatively moderate shifts to the left as slippery slopes that would doom everything. And because he thought those would doom everything, he pushed back really hard and ended up losing everything.

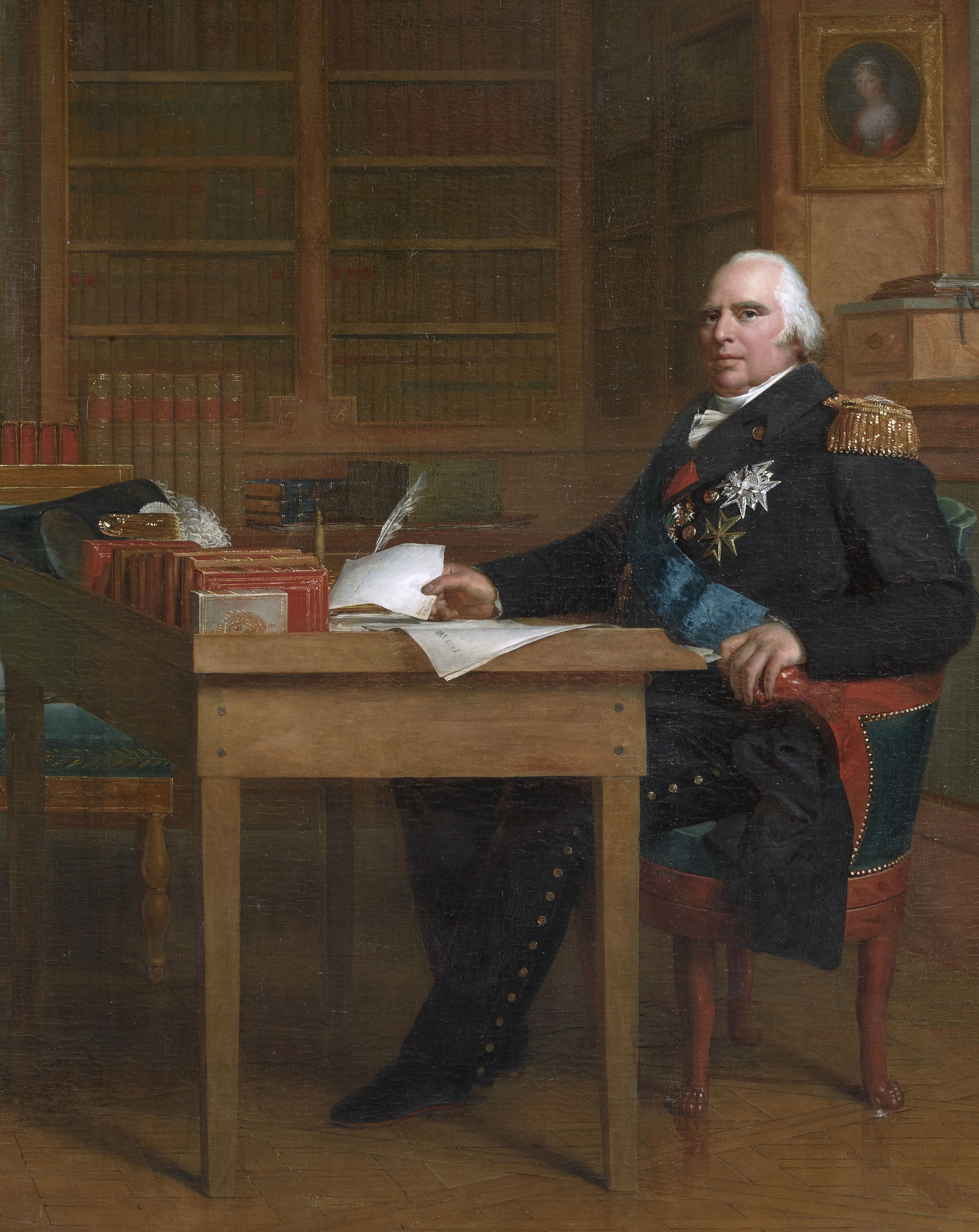

DUNCAN: Yeah, for sure. And of the three Bourbon brothers, the best of them was — in my opinion — Louis XVIII. Right?

DUNCAN: Yeah, for sure. And of the three Bourbon brothers, the best of them was — in my opinion — Louis XVIII. Right?

Right: Detail from Michel Marigny after François Gérard, “Louis XVIII meditating on the Charter, seated at his desk in the Tuileries Palace,” 1824. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

So he sort of operated in the middle ground between the post — you know, wanting to not have the verdict of the Revolution be the overthrow of everything that was good and pure about the ancien régime, but having some sense of what the practical lay of the political land was in the 1820s, which Charles was just going to be deaf to. Because, yeah, like you said, it’s very similar to where Charles I was during the English civil wars and where Nicholas is during the Russian Revolution, is these guys do believe that they have been anointed by God to be the monarch of France, or the monarch of England, Scotland, and Ireland, or the monarch of Russia — and they had a sacred duty to keep those things in place and to restore those things. I mean, Charles [X of France] was really Catholic. He believed all of that stuff. And so, he had internal justifications for what he was doing, he was just blind and deaf to the realities of the world he was living in in the 1820’s.

SIÈCLE: Your mention of Louis XVIII brings up something that I’ve wanted to talk about and get your reaction to, which is something that really struck me when I was writing about the 1830 Revolution: the comparison with the crisis of 1820 ten years earlier —

DUNCAN: Mmm hmm.

SIÈCLE: — which, to remind listeners, the late 1810s had been sort of the Liberal Restoration period. Louis, under his advisor Élie Decazes, had been making various liberal reforms. This was scaring a lot of the conservatives: they thought France was going — things were getting out of hand.

And then the Duc de Berry, the effective heir to the French throne, got assassinated and there was a huge crackdown. Royalists panicked over liberals running elections, they responded by imposing censorship, rewriting the electoral laws to privilege the richest voters, and they faced down street protests in response to that. But in 1820, the regime held. The protests were put down without serious violence. The regime was emboldened for another six or seven years without serious challenge.

Then fast-forward to 1830, you have royalists panicking over liberals winning elections. They respond by imposing censorship and rewriting electoral laws to privilege the richest voters. They faced street protests — and this time, everything blows up. They’re very similar circumstances.

I’m wondering, with all the revolutions you’ve looked at, what stands out to you about this, and in general about what factors influence when a crisis like this spirals into revolution, and/or gets successfully managed by a government?

DUNCAN: It’s a really good question, and I’m not sure that I have a great answer for you. Other than, you know, there are some differences between Louis XVIII’s personality and how he had been operating, and how he had managed to at least co-opt and get buy-in from some of the more conservative liberals who existed out there. Versus Charles X, who was far more confrontational, and far more willing to alienate any and all liberals. He’s not trying to placate anybody, and I think that that plays a big role in it.

And then, there is inside of — what’s going on in 1820 is a European-wide issue, because the death of Berry was being linked to the liberal revolution in Spain. And so it wasn’t just something that was happening in France, it seemed to be something that was much wider-spread, and so there was a desire to clamp down on it, but also understand that they couldn’t go as far as Charles wanted to go. I don’t think that even Louis XVIII was going as far as Charles was going to go.

Louis-François Charon, “Horrible Assassinat de S. A. R. M.gr Le Duc De Berry,” c. 1820. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And then it also comes down to sort of the way that the crackdown unfolded, where — in the case of 1830 — Charles drops the Four Ordinances kind of out of the blue. And it’s a direct and dramatic attack on what is happening, and is a direct attack on what is happening and has been happening for the previous three years, which is the liberals consistently gaining momentum because of the things that Charles is doing. Disbanding the National Guard, but sending them all home with their guns, for example. That’s where 1830 comes from, partly, is that all those disbanded National Guardsmen still had their guns — and so when it was time together in 1830, they were like, we’ve got an armed National Guard ready to go to overthrow this guy. None of that existed in 1820. The liberals didn’t have a ton of momentum going in 1820, and they certainly didn’t have a completely disbanded National Guard that was fully armed, ready to march into the streets of Paris and overthrow the monarch, should it come to that.

And then also, sometimes I think that there’s a degree to which the passage of time helps too, because in 1820 we’re just five years from the fall of Napoleon. They have just gone through an entire generation of war, struggle, turmoil, revolution. And I do think that there was probably some level of exhaustion with all of that that was prevalent in 1820 that was not prevalent in 1830, because some time had passed, and now you could look back on the revolution as something to inspire you and something to reach for, rather than something that is going to reopen the can of European-wide war, death, and destruction.

SIÈCLE: I want to press on two sort of very different explanations that I’ve seen and thought of when comparing these to, which sort of push in different directions. One is contingency: in 1820, there was a big protest; there was marching in the Tuileries and it started raining, and everyone went home. And ten years later, it was hot and sunny the whole time.

DUNCAN: Yup.

SIÈCLE: So, the first, the degree to which just luck like that can affect things.

DUNCAN: Hundred percent. Add it to the list.

SIÈCLE: And the second thing is the contrast between the management style of Louis XVIII’s prime minister at the time, the Duc de Richelieu — who generally comes off pretty well in the histories that I read — and Charles’ prime minister, Jules de Polignac, who, to put it mildly, does not come off well in the histories —

DUNCAN: (Laughter)

SIÈCLE: — even among his fellow ministers.

DUNCAN: Yeah. Yeah, yup. Polignac is one of my favorite characters from all the revolutions that I have ever covered. And yeah, personnel absolutely matters. Leadership absolutely matters. And Polignac was just — the guy — my understanding of Polignac is that he had been arrested during the Revolution and spent a good period of time kind of in solitary confinement, or at least confined. And that he came out of this a little loopy and a little off. And he was an arch, arch conservative.

DUNCAN: Yeah. Yeah, yup. Polignac is one of my favorite characters from all the revolutions that I have ever covered. And yeah, personnel absolutely matters. Leadership absolutely matters. And Polignac was just — the guy — my understanding of Polignac is that he had been arrested during the Revolution and spent a good period of time kind of in solitary confinement, or at least confined. And that he came out of this a little loopy and a little off. And he was an arch, arch conservative.

Right: François Gérard, “Portrait of Jules de Polignac,” circa 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And we should, of course, remember that the only reason he gets appointed as prime minister is because the liberals in the assembly are demanding that that Charles get rid of his previous prime minister and put somebody new in the prime ministership, and they’re all expecting him to go with somebody who was more liberal who will placate them, and instead Charles reaches into the bag and pulls out the most arch conservative person he can find. This is inflammatory, and deliberately inflammatory, and that’s also sort of what gets the revolution going. And yeah, if Polignac had been at all competent, they probably could have ridden this thing out. And for sure, one of my very favorite moments, honestly, of all the revolutions that I’ve covered, is in the Revolution of 1830. I think on the first night, Polignac and I think the Minister of the Navy, I think it’s the Minister of the Navy who’s telling this story —

SIÈCLE: Baron d’Haussez. (Right: Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez, unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

SIÈCLE: Baron d’Haussez. (Right: Charles Lemercier de Longpré, Baron d’Haussez, unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

DUNCAN: Yeah, exactly. And they’re walking along, and Polignac is like, “Oh, I suppose I should probably alert the troops that there’s going to be trouble in Paris.” And the Minister of the Navy is like — “You didn’t alert them already? You knew you were going to drop the Four Ordinances. You knew that it would spark a backlash. You knew that it would be controversial. And you just didn’t tell the army that you were probably about to spark a riot in Paris? What are you doing?” And Polignac says, “Nah, it’ll be fine.”1 (Laughter.) And they’re all overthrown like three days later.

SIÈCLE: That brings up another topic I wanted to talk to you about, which is — one of the very striking elements in 1830 was the role of what I call the “softliners” of the regime: the people who are fully supportive of the Bourbon Restoration. They’re conservative, but these people keep coming out of the woodwork to say — they come up to Charles and Polignac to say, “You’re making a mistake. You’ve got to change course or else everything is going to fall apart,” and they just get ignored. Softliner after softliner comes out of the woodwork — eventually they get through, but too little, too late.

DUNCAN: Mmm hmm.

SIÈCLE: And I was wondering: this archetype, do you see this as a recurring feature of other revolutions you’ve covered?

DUNCAN: Yeah, there’s always going to be a group of regime supporters who — their fundamental emotional state in the lead-up to the revolution is frustration, and they’re frustrated with the monarch. You know, supporters of the regime in the English Civil Wars, the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, like all of these — you find those people who are saying, “If you keep doing these stupid things, we’re going to lose everything. So we either need a more competent prime minister, or you need to hand off some of your decision-making to somebody else” — or sometimes, in places, eventually it becomes like, “We need you to resign or abdicate the throne in order to keep the regime itself intact. Like, if you want the Romanovs or the Bourbons to continue to be the royal family, then you’ve got to go. Your heirs, your son, your grandson, whoever, can become the new tsar or the new king, but you’ve got to go,” because they’re fundamentally frustrated with the incompetence of the people who are supposed to be the leaders and the defenders of the regime that they themselves support.

None of them are revolutionaries, in any way, shape, or form. When Nicholas II abdicates, he doesn’t abdicate because Lenin came and put a gun to his head and said it’s time to abdicate — Lenin’s not even on the scene yet. It’s a bunch of Russian nobles and ministers on a train with Nicholas saying, “Dude, you have to go. The only way to save anything or salvage anything is for you to abdicate.” But they don’t want Tsarist Russia to end. They don’t want the system to end, they’re just trying to protect it. And that sort of class of people and archetype of person is present in just about every revolution I’ve ever covered.

SIÈCLE: It seems like their behavior and where they come down can be a decisive factor in whether a revolution succeeds or not. Whether these people stay loyal to the regime or whether they start pushing it toward an exit.

DUNCAN: Yeah, one of the things that — again this emerged kind of organically from just trying to tell the stories of these various revolutions as they’ve gone on — is that revolutions don’t happen just because the masses or the people or the proletariat rises up and overthrows their class enemies. It’s always this big sort of hierarchical vertical structure that links disaffected nobles and elites at the very top all the way down to those people — who are absolutely necessary.

Like, the revolutions don’t happen without those masses of people rising up and taking out the Bastille and fighting on the barricades for three days, but that the disaffected nobility is really an important part of this, and one clique of them are going to be like what we would call the liberal nobles who really do want like genuine reform. They see the injustices and things that are broken about the regime as it currently exists and they want to change them and they want to reform them, and these guys are all over the Revolution of 1830. This is Guizot, this is Jacques Laffitte, right, who — they want a different version of France, but have the elite capacity and money and resources and access to the inner circles of power to actually affect a regime change.

And then you also have, as we’re just kind of talking about, the same class of people, except they’re [not] defenders of the revolution — but they’ve lost confidence in the sovereign himself. (It’s always himself, so far as I can — every revolution that I’ve covered, they’re overthrowing a guy.) But it’s that level, that loss of confidence that does pull one of the Jenga pieces out for the entire thing to fall over, for sure.

SIÈCLE: Just very briefly, focusing on that other group you mentioned: the liberal reformers, the liberal nobility — the people who are okay with a little revolution, but not too much.

DUNCAN: Yep.

SIÈCLE: I think it’s not too much of a spoiler to say that this group often doesn’t come out well in the end in a lot of these big revolutions.

DUNCAN: Yep.

SIÈCLE: But [in] 1830, they sort of do — at least in the short term. Can we talk a little bit more about these liberal reformers, these liberal noble types, and what made 1830 relatively successful for this group?

DUNCAN: Yeah, these are people — there’s kind of two versions of liberal nobles. There’s the liberal nobles who want to enact a bunch of reforms to the regime and change it and alter it in several ways, in order to sort of protect the social system as it exists and the class standing of everybody and they see revolutionary upheaval as a means of just getting the changes in place that will prevent further revolutions, right? Those guys don’t actually want revolution at all. They don’t actually want to be revolutionaries. They want the reforms to go into place to prevent a further revolution from happening. And I think in 1830 this is best represented by like François Guizot, who comes out of the French Revolution believing the French Revolution was bad and terrible2 and didn’t want to go through all that again, and he was going to do the absolute minimum amount necessary to prevent future revolutions from happening by enacting like very, very, very limited reforms.

DUNCAN: Yeah, these are people — there’s kind of two versions of liberal nobles. There’s the liberal nobles who want to enact a bunch of reforms to the regime and change it and alter it in several ways, in order to sort of protect the social system as it exists and the class standing of everybody and they see revolutionary upheaval as a means of just getting the changes in place that will prevent further revolutions, right? Those guys don’t actually want revolution at all. They don’t actually want to be revolutionaries. They want the reforms to go into place to prevent a further revolution from happening. And I think in 1830 this is best represented by like François Guizot, who comes out of the French Revolution believing the French Revolution was bad and terrible2 and didn’t want to go through all that again, and he was going to do the absolute minimum amount necessary to prevent future revolutions from happening by enacting like very, very, very limited reforms.

Above: Jehan Georges Vibert, after Paul Delaroche, “François-Pierre-Guillaume Guizot,” circa 1837 (Delaroche). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And then, there’s the liberal nobles who believe that the revolution is meant to be the first step on a larger process of prolonged and large-scale reform, and I think Lafayette is in that group of liberal nobles. Where Lafayette comes out of 1830, and he thinks, “Great, we’ve done the first step. Next, we’ll move onto like enfranchising more people, and then we’ll like expand rights and we’ll expand the electorate,” and he, himself, finds himself on the outside by the end of 1830 because the Party of Resistance, which is those conservative liberals, are going to win in 1830 in a way that they did not win, as you say, in these other revolutions — or those people are eventually overthrown.

And the big moment here is then, nothing that happens in 1830, really — it’s the failure of the revolution in 1832, the June Rebellion of 1832. Which, when you sort of track the course of other revolutions, there is that sort of first wave, often liberals, often led by the elites, who want those kinds of reform projects. And then two or three years later, there’s kind of like a more radical uprising. This is what the August Insurrection of 1792 is about. This is the difference between the February and the October revolutions in Russia.

And in the case of the Revolution of 1830, that is really what we see in 1832, when the collection of these neo-Jacobin students and junior officers attempt to do an insurrection of August 10 and overthrow the July Monarchy because it had been betraying what they thought the revolution of 1830 was about. And then — that one, 1832 — doesn’t work because their numbers are minimal. And I think that there’s also like — Louis-Philippe is out there on the front lines. The National Guard stays with Louis-Philippe, rather than going over to the revolutionaries. And often in French history, wherever the National Guard goes, that’s the side that’s going to win in whatever factional conflict is going on inside of some French revolutionary event. And in 1832, I think Louis-Philippe shows real leadership, and instead of hiding in the palace, he goes out there on his horse and he’s kind of on the front lines. And the National Guard really sticks with him, and so they put the rebellion of 1832 — they make the rebellion of 1832 merely a rebellion and not a further revolution. But all that just pushes it just deeper into — it pushes under the surface, but it does not make it go away, and so a lot of what happened in 1832 just comes roaring back in 1848 and then again in 1870. And so, yeah, they were successful for like 18 years, but then they do ultimately all get overthrown in a further and more extreme and radical vision of revolution.

SIÈCLE: We’ll be talking a lot more about the June Rebellion of 1832 in future episodes of The Siècle.

Something else that really stood out to me about 1830 was just how fast it was compared to these other revolutions. If we look at the American Revolution, there were a lot of people who were squishy moderates in the beginning who weren’t okay with independence and eventually they came around. But they had months and months and months of time and pressure to evolve. And people like François Guizot or Casimir Périer had to go from non-revolutionaries to revolutionaries over just the course of a couple days.

DUNCAN: Yeah, and that’s one of the things that makes 1830 more of a template for future revolutions a little bit because it was — you know, 1830 is like a lightning coup more than anything else. It is done by an uprising of the people of Paris, but all of the initial fighting and everything was kind of just in Paris. It didn’t have time to spread elsewhere. By the time most of the rest of France was even learning that there had been this revolt in Paris, they were also being told, “Oh, and by the way, it’s over. The king has abdicated and Louis-Philippe is your new king.” And people were like, “Oh, I guess that happened.” And there just wasn’t enough support for Charles X out there, really, to push back against it. And it was actually one of the most surprising things. You sort of get into the aftermath of 1830 and the rest of France just kind of acquiesced to it very, very quickly, and I think it does speak a little bit to the general tenor of politics in the latter 1820s and into 1830.

Because I wrote this biography of Lafayette, I am pretty intimately familiar with what he was up to, and there were a lot of, you know, campaign events and banquets across France in 1827 and 1828, and 1829, that [were] building momentum for the liberal cause and really ginning up support for the liberal cause in all of those other French towns and French cities and French villages. So that I do think they were all primed, ultimately, to be surprised by the news that there had been a revolution in Paris and Charles X had been overthrown — but not regret Charles X’s overthrow, and not really be like, “Oh, we need to push back or stop this.” They were kind of just willing to accept it.

And yeah, it happens very, very quickly. Nobody expected it to happen. Again, there’s a famous funny note from Lafayette where he’s like, “Well, I’m going to go back home, because it doesn’t look like anything’s going to happen in Paris — at least until September, when we have these new elections that Charles has called for.”3 And then like days later, he’s back in Paris putting on his National Guard uniform because there was a full-blown revolution.

SIÈCLE: It’s as good a time as any to talk about Lafayette. You wrote a biography of Lafayette, The Hero of Two Worlds; I’ll include a link in the transcript of this episode for people who want to check that out. And Lafayette wasn’t around for the first day-and-a-half or so for the July Revolution. As you said, he was out in the country because didn’t expect any of this.

DUNCAN: (Laughter.) Because nothing was going to happen.

SIÈCLE: Which undermines the claims some of the Ultraroyalists [had] that this was all a conspiracy and was planned —

DUNCAN: Oh yeah, this is the printers — this is the printers getting pissed off.

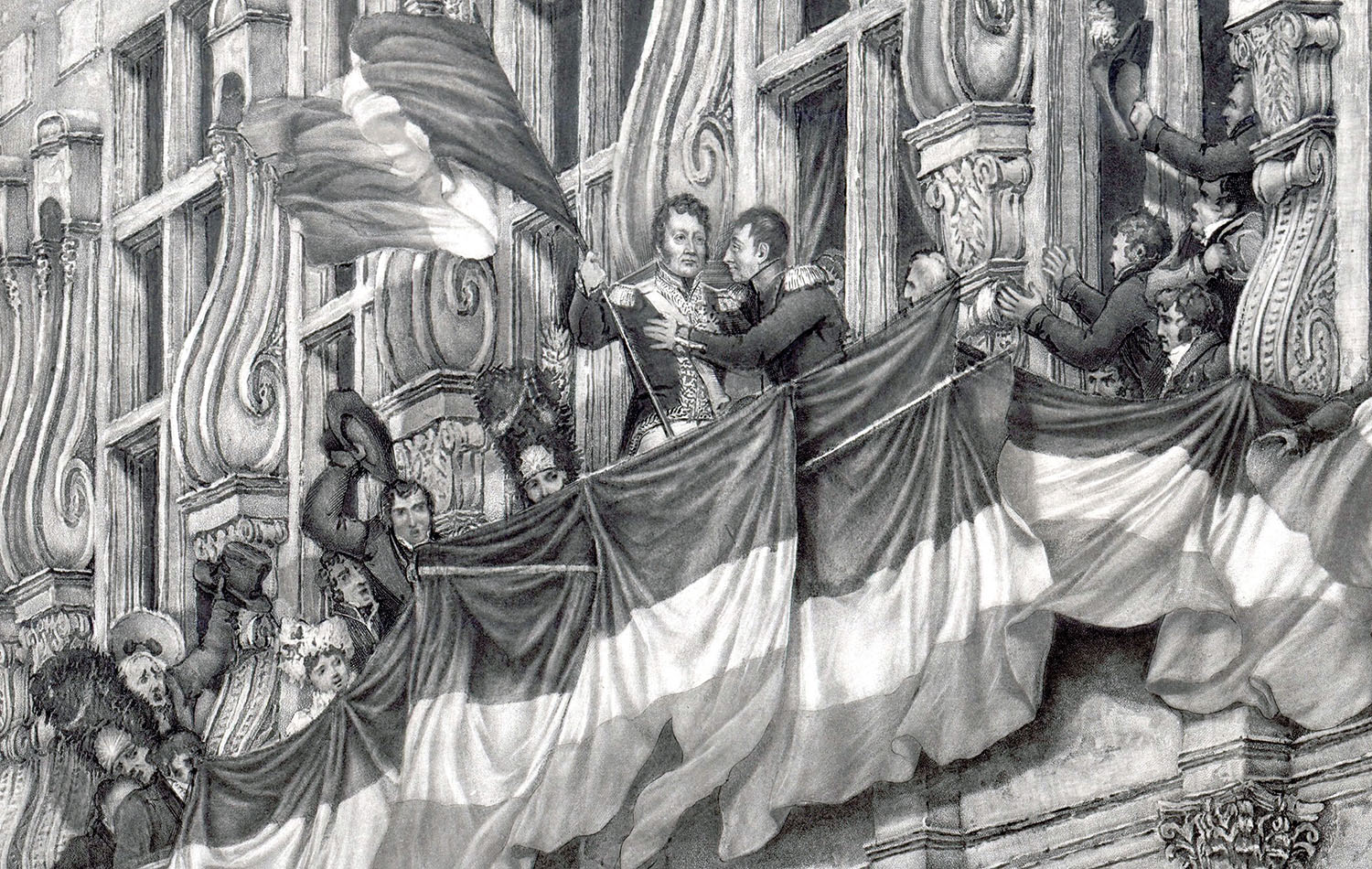

SIÈCLE: But Lafayette ended up being pivotal, arguably the central character of the sort of Thursday, Friday, Saturday — these big events — starting with when he takes over the Municipal Commission, ending with his famous kiss on the balcony with Louis-Philippe. Explain a little bit more about what was going through Lafayette’s head. What was his role in all this? Obviously, he was seen as really on the left, but then the true republicans thought he was not nearly enough on the left. Talk about the role of the Marquis de Lafayette — or General Lafayette, as he preferred to be called.

DUNCAN: Yeah, at this point he wants to be known as General Lafayette. So, Lafayette, after the Restoration, he gets back into politics. And he has been a liberal deputy off and on all the way through between — I forget what year he was first elected. Maybe 1818, maybe 1817, I forget.4 All the way through, and he’s a delegate in the assembly during 1830. And had tried and failed to stage like a revolutionary mutiny inside the army with the Carbonari in the early 1820s. And so, Lafayette was personally not reconciled to the restored Bourbon regime. He thought that it was rolling back way too many things that were, in his mind, sort of final verdicts of the French Revolution that were being rolled back.

Lafayette himself is, still, one of the most famous people in France. People know the name Lafayette. This guy has been around since 1777; people have known the name Lafayette since 1777, since he first went to the United States. So he, himself, is a popular figure and a well-known figure, and there’s a lot of people who will look to him, his connections to America, his connections to George Washington — you know, the great republican revolutionary — as somebody with an authoritative voice.

And so, when he comes into the Revolution of 1830, not having expected that it would happen — but as soon as he finds out that it happens, he’s like, “Yeah, let’s go do this thing.” As soon as he comes walking in the door with some of the meetings with some of these liberal leaders that are taking place in Paris, he’s like, “Yeah, the king’s already abdicated. By his actions, he’s already abdicated the throne and we can and should do everything in our power to make sure that abdication” — which, you know, Charles hadn’t signed a piece of paper yet — “to make sure that that abdication happens.”5 And then he goes forth with his fame, with his voice and says, “We’ve got to overthrow Charles.” And I think that him having that voice that affected people — and probably people who were on the fence about it were like, “Okay, well, Lafayette’s going to go along with this.”

He becomes the pivotal figure, I think; this is one of the moments when Lafayette really influences the course of history — and maybe not, in Lafayette’s own mind, to the best result. Because he’s the one who more or less secures the throne for Louis-Philippe.

Above: Detail from Ambroise Louis Garneray, “The Duc d’Orléans Is Presented to the People by the General Lafayette on the Balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, July 31, 1830,” after 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I do think that it is Lafayette deciding to back Louis-Philippe over some of the several other options that were available — because, you know historical contingency, like you say, exists — and there [were] at least four different options that were on the table coming out of the abdication of Charles. It was like: his grandson could inherit the throne, the Bonapartists wanted to bring an heir to Bonaparte back, republicans wanted it to be a republic, and then there was this, “Let’s give it to the cousin of the Bourbons, the Duc d’Orléans.”

And of those four, Lafayette believed that transferring power to the Duc d’Orléans to make him King Louis-Philippe was the path that was going to do the least amount of damage to France, the least amount of damage to Europe. Not trigger a war, not trigger civil war. And that’s what was really on his mind in 1830, and he’s very clear about this. Like he writes about this in various places, where, in his mind, if they had, for example, gone with a Bonapartist candidate to succeed Charles X, that’s bringing back Napoleon. Every other power in Europe is going to be scared and hostile to the restoration of the Bonapartes, because the Bonapartes just stand for war with the rest of Europe, and it probably would have triggered war with the rest of Europe.

And then, he believed the same thing about a republic. You know, Lafayette believed in republicanism, and he thought it was a good thing, and it was ultimately what every policy should be aspiring to, but the word république and republic in the rest of Europe was, again, not a signifier of revolutionary freedom and liberty, but war. Just war. Like the republic declared war on the rest of Europe, and the rest of Europe declared war on the French Republic.

And so, to go with those things would so completely inflame the situation elsewhere in Europe that those powers would almost feel obliged to get their armies back up and running and re-invade France — which, remember, they had just done fifteen years earlier. The only reason that the Bourbons were in power is because the other European powers came in and installed them on the throne and then kept them on the throne thanks to occupation forces. France was occupied for several years after 1815. And so, he saw all of those things as being like, “No, if we go with any of those other options, it’s just going to be war, death, destruction, and probably the reinstallation of a Bourbon.”

And then, Lafayette himself was now completely done with the Bourbons. He’s like, “These people cannot be in power ever again. They’re the worst. They’re never going to see reason, they’re never going to accept the verdict of the Revolution, so they’ve got to go.” So the only thing that is left is Louis-Philippe. And so, Lafayette is like, “Okay,” and Louis-Philippe says the right things to Lafayette, and Lafayette lets himself believe all the things that Louis-Philippe is saying. And I don’t think it was necessarily out of line for him to believe the things that Louis-Philippe had been saying before he becomes king, because Louis-Philippe had been more liberal, and the Orléans family had been more liberal. Louis-Philippe’s father was the Duc d’Orléans, and then Philippe Égalité during the French Revolution, and had been a major player in the French Revolution.

So I think that there was decent reason for Lafayette to believe that Louis-Philippe would be on the side of sort of liberal reform and ongoing reform. And then as it turned out, Louis-Philippe was far more conservative and just wanted to do the bare minimum number of reforms necessary to quell the situation and then nothing else.

SIÈCLE: And that’s one of the things I’ll be hoping to dive into in the next couple episodes of The Siècle, looking at the degree to which — how contingent was the July Revolution’s turn to conservatism — whether it was baked in, or whether another route was possible. A comparison with England and Reform Act is going to come up a lot.

But I wanted to — you mentioned Louis-Philippe and his father, Philippe Égalité — I think that the three main characters here, all old men: Charles X, Louis-Philippe, and Lafayette, had all been active in the original French Revolution and were all shaped by their experience there. I talked about how Charles X thought that it was the compromises that had kicked off the French Revolution and was determined not to repeat that.

Louis-Philippe wrestled with accepting the throne to some degree, because he was traumatized by his father’s decision to ultimately betray the Bourbons and vote to execute Louis XVI. And he seems to have some genuine, real hesitation about repeating that by usurping the throne.

And Lafayette — in the Bourbon Restoration, Lafayette was as left as left went in French politics. But of course, in the actual French Revolution he was far outflanked by the Jacobins, and the neo-Jacobins were still out there, and Lafayette was in sort of an ambiguous position where he was a sort of a representative of the left, but was not the farthest to the left and had these memories of what happened when the people farther to his left won.

DUNCAN: Yeah, Lafayette was absolutely not on the far left. And again, one of the things that will happen in 1832 when you guys get to that is that — that revolution, that revolt breaks out basically at Lafayette’s feet. He was enough of a representative of, sort of republicanism and revolutionary reform that they believed that if they went into revolt at Lafayette’s feet in the midst of Lamarque’s funeral procession, that Lafayett would lead them. And they tried to thrust the red liberty cap in his hand. And the story is that he threw it to the ground because that red liberty cap represented to Lafayette sort of the dark turn of the revolution, which dispossessed him of all his property and killed most of the people in his family.

Like, all of his inlaws kind of get fed to the guillotine in 1794. And his wife would have been fed to the guillotine in 1794, had not James Monroe and Gouverneur Morris intervened with the French foreign ministry and said, “If you kill Lafayette’s wife, you’re going to have a big problem with the United States.” But Lafayette also like, even with all those things that happened to him and around him, still believed that the Revolution in itself was a good thing — it had just been kind of taken over by people who maybe weren’t the best people to lead France. That’s in his opinion. But the people who are trying to rise up in 1832 are those neo-Jacobins who look at Robespierre and Danton not as villains of the revolution, but as true heroes of the revolution.

Like, all of his inlaws kind of get fed to the guillotine in 1794. And his wife would have been fed to the guillotine in 1794, had not James Monroe and Gouverneur Morris intervened with the French foreign ministry and said, “If you kill Lafayette’s wife, you’re going to have a big problem with the United States.” But Lafayette also like, even with all those things that happened to him and around him, still believed that the Revolution in itself was a good thing — it had just been kind of taken over by people who maybe weren’t the best people to lead France. That’s in his opinion. But the people who are trying to rise up in 1832 are those neo-Jacobins who look at Robespierre and Danton not as villains of the revolution, but as true heroes of the revolution.

Left: Horace Vernet, “King Louis-Philippe I,” 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And so, Louis-Philippe lived through all this. He was a young man, he was a very minor figure in the French Revolution itself because he was young. He served in the army for a bit and then basically had to run for his life and winds up in exile in the United States for several years. But he always “fought under the tricolor.” You know, that’s what you can always say about Louis-Philippe — he fought under the tricolor, and that was really the only thing anyone really knew about him.

But yeah, Louis-Philippe definitely was traumatized by the things that happened, and more than Lafayette, took the lesson from that being: we need to put a lid on revolution as quickly as possible, even if it serves our political interests. And Lafayette was like, “Let’s let it play out, and try to get as much out of this as we can,” but even Lafayette has his limits to how far he wants it to go.

SIÈCLE: By the time this episode comes out, you will have finished up your series on the Martian Revolution, which is the sort of fictionalized retelling of revolution that’s drawing on all of these actual historical revolutions. Talk a little about this project, and what if anything you’ve drawn from 1830 in particular to inform some of these characters and events that you’ve talked about in this fictional story of the Martian struggle for independence.

DUNCAN: Okay, so what I did — I did this ridiculous thing where I took everything that I have learned about the nine or ten revolutions that I covered before now, up to sort of the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917, and extracted from that large, archetypical patterns of the course of events. Again, I’ve mentioned this a couple of times, there’s usually like a first wave, and then there’s a second wave that overthrows them, and then are liberal nobles, and there’s an idiotic sort of sovereign who’s making a hash of things that allows all this to get going in the first place. And then there’s radicalization, there’s civil war, there’s counter-revolutionary royalists. Like all of these things kind of exist in all the different revolutions that I covered.

So I extracted all that, and then use that architecture and all of those events and examples and painted over it a story that is a fictional historical account of a revolution on Mars in 2247 which is told from the perspective of a narrator who is living 250 years after the revolution happened. So he’s able — which is basically like, we’re 250 years from the events of the Atlantic revolutionaries, so that’s basically what I’m going from here. And so, that narrator is able to look back with the fullness of time; we have all the sources, we’ve lost some sources, there’s historiographic debates, there’s an entirely made-up bibliography that explains — “if you want to learn more, read this book” — and all of this is just, I’m making it up off the top of my head. And I’m running through the structure and the patterns of historical revolutions but doing it in an entirely science-fiction setting for the fun of it — because I think it’s really fun, but also because I think it’s another way of looking at and examining the historical events that inform this story.

And people who listen to all the episodes of Revolutions before they get to Mars can look and say: oh, Vernon Bird, that’s very clearly like Porfirio Díaz, and that guy over there, he reminds me of — that looks like Danton and Desmoulins, and that’s a Lenin figure and — all of those things exist in there, so it’s just kind of a different way to think about revolutions.

When it comes to 1830, specifically, I think the main things are: I definitely had to have barricade fighting — because barricades become one of the physical symbols of revolution and have been ever since, so there’s definitely barricade fighting in the Martian Revolution. And then there’s also like sort of in 2247, when the first revolution happens, there is inside of the elite, the local Martial elite, there are sort of liberal nobles who want independence for Mars and who want to reform the social system they had been living under, represented by one of the main characters, whose name is Mabel Dore. And then there’s also in that same group like those conservative liberals who are like, “Ahh, I don’t really want to reform the social side of things. Like independence for Mars is good, but I don’t want to do the rest of it.” And I think I was thinking a lot about what happened sort of after the July Revolution as one of those archetypical moments when you do get a split amongst those sort of conservative, moderate, and more extreme liberals, outside of the more radicalized sort of social revolutionaries that are going to rise up and overthrow them — which ultimately does have to happen in the Martian Revolution because that’s what happens in revolutions so very often.

SIÈCLE: Are there any other thoughts you had about the July Revolution that we didn’t get a chance to talk about that you wanted to be sure to share before we wrap up this part of our talk?

DUNCAN: There’s nothing that immediately springs to mind except that the Revolution of 1830 is — it’s a very under-covered revolution but it does — it’s very entertaining. There’s a lot of entertainment value in the Revolution of 1830. There’s some good characters doing some kooky stuff. And really, in the end, the Revolution of 1830 should have never happened. And it happened because, again the 1830 [Revolution] becomes one of the sort of pillars of the idea that it’s incompetent leadership more than anything else that will trigger a revolution.

And when I talk about that out in the world, the examples I’m always pulling from is Charles I, of England, Scotland and Ireland who — there was no reason for any of that to have gone on, he just made it happen with his own stubborn insistence on ruining everything — and Charles X of France is my next principal, go-to example — him and Polignac. So, sort of understanding what happened in 1830, I think, does give you a great perspective on that part of a revolutionary event, which is how leadership can so fundamentally blow a situation that they trigger a revolution that never should have happened.

SIÈCLE: I wanted to wrap up our talk by pulling away from the history to talk about this medium we both share of narrative history podcasting.

DUNCAN: Mmm hmm.

SIÈCLE: You’ve been doing this for a lot longer than I have, but what attracts you to this medium? What do you think it does well as a medium for teaching and learning history? And what are its challenges and shortcomings?

DUNCAN: Well, the main thing that podcasting gives people is something to listen to while they are doing something else. And I think that that’s really kind of where podcasts live inside of people’s lives. Certainly, that’s how it lives inside of my life. If you ask people, when do you listen to podcasts, it’s when I’m doing the dishes, it’s when I’m exercising, it’s when I’m stuck in a car on a commute. Those are the times when people engage in podcasts. You rarely hear people saying, oh like, I listen to podcasts when I sit on the couch and just listen to the podcast and nothing else. That’s not really how I think people take our shows in.

And what’s great about that is what that gives us, really as a society, is an opportunity for people to learn about stuff and be educated about things that they would not otherwise be educated about because they’re learning about it when they’re busy doing something else. And if we force people to rely only on books, or TV shows, or video documentaries, or whatever, that requires kind of their full attention and not doing anything else, I think that we are missing out on a golden opportunity to turn all of these kinds of drudging moments of our lives into something that is actually worthwhile and beneficial and enriches our lives.

So, that’s the thing I like best about podcasts, and that’s what I think we do best is we turn those boring and sometimes really aggravating moments in the case of, like, a long commute — and make it something that is fun and enriching and great.

The challenges of it are, of course, that there is no visual component at all. And so, you can obviously put it on YouTube and you can have videos and pictures and stuff being shown, but it’s an audio-only medium. And so it’s more difficult to flip back and say, “Wait, who was this person again?” Which I do all the time in books: “Wait, who was this guy again?” And then I can flip back like three pages really quickly and be like, “Oh yeah, yeah, it’s that person.” It’s much harder to do that in an audio podcast than it is with a physical book.

And then, of course, it just comes down after that to how well you work on and craft the narrative and how hard you work at making sure you get your information right, because we do live in a world of misinformation and disinformation and people sharing things that are just completely dead wrong. I’ll listen to history podcasts or watch history documentaries and I’m like, “Well that’s not true, and that’s not true — where are you even getting any of this stuff?” And so, that stuff is also proliferating in a way that is like, “Yeah, how do we ever check the spread of wrong information?” But from my perspective, and I’m assuming your perspective, the best way to combat this is to know for ourselves how much time we put into reading the sources, understanding what happened, and only telling stories that can be backed up in books and from primary and secondary sources to make it like a solid narrative that is actually educating people instead of misinforming people.

SIÈCLE: Plus, occasionally, maybe one or two quotes that are just too good to check.

DUNCAN: Yeah. Of course. (Laughter.) Yeah, you know, there’s a little bit of “print the legend” in there. You know.

SIÈCLE: I think that’s particularly the case in July, 1830 because a lot of what we know about it comes from people’s memoirs written years after the fact, in which —

DUNCAN: Yeah.

SIÈCLE: — everyone comes off suspiciously prescient about the dangers of what was going to happen, and it’s always a little uncertain about how much one can trust all that.

DUNCAN: Yeah, and I think all throughout the Revolutions podcast, and even going back to like Roman history — because this is even more true in Roman history, where you’ve got, you know, stuff written 500 years after the fact by like, some random senator who like was not even close to there and doesn’t even have primary sources. So it’s important to keep the listener — sort of constantly reminding them that like, “Yeah, we’re getting this from memoirs and memoirs are entirely self-serving,” and, “We’re getting this from somebody who was not there. We’re getting this from somebody a hundred years after the fact.” As long as I think you introduce the notion that there is ambiguity and there is trouble with the sources — and some things we’re never going to know, and some things are clearly biased — as long as you’re pointing those things out, I think we’re setting our listeners up for success.

SIÈCLE: Sometimes someone just has to have reportedly said something.

DUNCAN: Yeah.

SIÈCLE: If you look at the leaderboards of the most popular history podcasts out there, you’re on there — Revolutions is on there. But a lot of the other most popular podcasts are episodic; they do a different thing every week. You’ve done serialized narrative history where you’re telling a long-form story over many episodes that are designed to be listened to in an order, which can be a heavy lift for some people. What attracts you to the serialized form of storytelling rather than sort of just jumping around and doing self-contained capsules that look at particular incidents?

DUNCAN: This, I think, is simply an accident of me getting it in my head one day to write a complete narrative history of the Roman Empire, back in 2007. That’s what I wanted to do. It didn’t even occur to me to do like, sort of one-off episodes — or, I’ll be a history podcaster who covers like this event and that event, and this person and that person, and every episode you can kind of come into it cold and just listen to it from start to finish and get a little capsule bit of history. Because the original vision for The History of Rome was a huge, all-encompassing, single voice narrative history of the Roman Empire, because that didn’t really exist. And I thought that it was something — it was something that I wanted to exist, but did not exist, and so I made it exist.

And that process of spending five years writing a narrative that covers a thousand years of Roman history — like when I went into Revolutions, yeah, it was just that. I had the idea of doing it somewhat episodically in terms of like, each series will be a different revolution. But within those revolutions, it is a big, continuous narrative. You are not meant to start anywhere but at Episode One of a given revolution, and if you just try to hop in, you’re never going to know what’s going on because it’s — it’s a soap opera, in a lot of ways. It’s just running soap operas, and you don’t have any idea of what happened before.

But that’s just how I’ve always done things, and other people do history podcasts their way, and I think there’s enough of those out there that I don’t have to change my mode of operation, even though — when I’m like, “Oh yeah, I did this great series on the Russian Revolution.” And somebody who’s never listened to the show is like, “Oh, great. How long is that?” And I’m like, “Oh — well, it’s 103 episodes,” and it’s, you know — I don’t even know how many, like a hundred hours of material or something? That’s probably an exaggeration. But yeah, it is a big lift. And then people are like “Oh, okay. Well, maybe I’ll try that another time.” Because asking someone to listen to a hundred and three episodes on the Russian Revolution is like a big thing. But I believe that my success and my continued success and the reason I’m still able to do this all these years later is that once people start at Episode One and get into the story I’m telling, I can keep people coming along with it week after week. Like you do want to find out what happens next, and then you do want to find out what happens next, and then the next thing you know — you’ve started at episode one of the Russian Revolution and you’re at episode 103 and you’re like — “Oh, well I actually kind of want this to keep going. This has been great.” So yeah, it’s a big ask and it’s a big lift, but long-form narrative history podcasting is what I’m going to be doing for the rest of my life.

SIÈCLE: You had a moment near the end of the Russian Revolution series where you went through and tied all the threads together; things you had been talking about for years had all come together in this moment. I imagine that must have been very satisfying to you, from a storytelling perspective, as it was to me, listening to that. I think it speaks to the power of the serialized narrative, where you are able to cover lots of disparate events that all come together at the end — because, of course, all these things are having impacts.

DUNCAN: Yeah, for sure. And the other thing that I really like about the long-form stuff is that like — I can just take the example of the French Revolution because it’s right there. A lot of times when you do the French Revolution, there’ll be like — there’s a lot of information about 1789 and the Fall of the Bastille, and then maybe you get into like 1792, and ‘93, and ‘94, like the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror. And then you kind of skip to — okay, and then Napoleon comes along.

But in-between those moments, those big moments that are always covered that would get like a standard episode treatment, we skip over 1790 and 1791, which is like two full years of events that come from what happened in 1789 and build towards 1792, that, if you just look at — “Okay, I want to learn about the insurrection of August the 10th” — we don’t really have the background to understand what actually happened. Whereas if you follow me through, I will tell you all about the sort of obscure stuff that happened in 1790 and 1791. And then later, like after the fall of the Committee of Public Safety, and after Robespierre gets overthrown, after Thermidor — you know, the several years of the Directory is often very neglected by history. But you go through that stuff and you understand where the Napoleonic Empire comes from, you understand how France went from being like a really sort of chaotic mess to this authoritarian war machine. Those things happened in 1795 and ‘96 and ‘97, which are always ignored, and so I always like when I get to the parts of these stories that are not usually covered, because there’s always interesting stuff happening in there, and they always better inform the big events that we’re sort of expecting to be talking about.

SIÈCLE: Well, I couldn’t agree more. Mike Duncan, thank you for coming on the show. Tell people about where they can find more of you and your history podcast, and books, and other projects — as well as what’s next for you.

DUNCAN: Well, you can find both The History of Rome and Revolutions anywhere fine podcasts are found. You know, we’re everywhere. You can just search for Mike Duncan or Revolutions or The History of Rome, and I have — as we just talked about — a lot of material for you to go through at your leisure.

I also wrote a book called The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic, which covers the couple of generations before the arrival of Caesar to explain what was going wrong inside the Roman Republic that leads to the overthrow of Caesar — which actually gets right back to the point I was just making, where like, everyone wants to talk about Caesar, and I want to talk about what happened a generation or two before Caesar that allows Caesar to be a thing. So that’s what The Storm Before the Storm is about.

And then also, hopefully of interest to all of you out there, I wrote a biography of the Marquis de Lafayette called Hero of Two Worlds, which is a cradle to grave biography of Lafayette. It takes him from birth, all the way through to his death in 1834. We cover 1830 in great detail. All the events of [the] 1820s, I cover in great detail. Because one of the reasons why I wrote that book is that typically, biographies of Lafayette cut off when he gets expelled from the revolution in 1792. And it’s like, “Okay, then he wound up in prison, and he retired, and later came back for this tour of the United States.” But no, no, no, no. Lafayette was deeply and heavily involved in French politics and revolutionary politics all the way to the end of his life in 1834. So both of those books exist.

I am currently — I’ve just wrapped up the Martian Revolution series. So, if you are listening to this, you can start at Episode 1. It’s a 29 episode-long history of a revolution on Mars in the far future, and so you can get at that. And then, once I am finished with my third book, which is another book about Roman history — it’s going to be about the Crisis of the Third Century — once that book is done and written, I return to Revolutions history podcasting full-time and we’ll pick up with new series that pretty much start after World War I. Because I left off with the Russian Revolution in the early 1920s and I’m just going to sort of pick things back up and cover all of the 20th Century revolutions that everybody wanted me to cover, and now I will.

SIÈCLE: Let it not be said that the people don’t get what they want in the end.

DUNCAN: Right. Yeah. Yeah, I am nothing if not a man of the people.

SIÈCLE: Alright. Well, Mike Duncan. Thank you very much.

DUNCAN: Yeah. Thanks for having me.

Thank you to Mike for coming on the show.

This episode was transcribed by David McLain. You can read the full transcript at thesiecle.com/episode46.

Thank you also to The Siècle’s network, Evergreen Podcasts, and to the show’s Patreon supporters. Since the last episode came out, new supporters include: Sam R., Olivier Dubois-Matra, Brian Gold, Atari Anushiravan, and Irène Delse. They and all other subscribers get access to an ad-free feed for as little as $1 per month. Join them at patreon.com/thesiecle.

Now, I’m headed back to the books to finish up the next episode, where we’ll return to France as the dust settles after the July Revolution, and the victorious politicians and people have to decide what kind of country they want this revolution to create. Join me next time for Episode 47: The July Settlement.

-

As quoted in Episode 43: The Politicians: “Even Polignac recognized the inadequacy of this, and said he would alert the commander of the Royal Guard about the disturbances. In his memoirs, Haussez describes himself being shocked: ‘Hasn’t that already been done?’ ‘You’re always worrying,’ Polignac replied.” ↩

-

I discussed Guizot’s more nuanced views on the French Revolution in Episode 29: Doctrinaires: “And yet, while the Doctrinaires applauded the Revolution’s victory over the ancien régime and sought to continue the fight, they had profoundly mixed feelings about the Revolution. The key for them was the difference between the early days of the French Revolution — the admirable ‘spirit of 1789’ — and the repugnant Reign of Terror. If Doctrinaires feared those who would return to the days of Louis XVI, they also feared those who would — in their minds, at least — return to the days of Robespierre.” ↩

-

Lafayette’s note of July 26, 1830, from his country estate of Lagrange: “It appears that it [a coup d’état] has been renounced for the moment; provisional moderation has been restored to the order of the day.” As Lafayette wrote that, the Four Ordinances had already been released in Paris. David Pinkney, The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 79. ↩

-

1818. ↩

-

Among Lafayette’s alleged quotes, as included in Episode 45: “Charles X, in truth, takes too much trouble in signing these acts; we have ourselves repealed the ordinances during the last three days.” ↩