Episode 49: The Trial

It was dark, but the crashing waves and cries of seagulls marked the nearby shores of the English Channel when the Marquise de Saint-Fargeau and her manservant arrived in town. They were in Granville, a French port in Normandy — a perfect place to catch a ship from France to England.

The noblewoman booked a room in a local hotel, but her late arrival immediately attracted suspicion. The nighttime travel might have attracted interest at any time, but these were not ordinary times. It was August 1830, and all France was in an uproar after the July Revolution just over two weeks before. So the innkeeper paid special attention to his new guests.

He soon became convinced something was up — not with the noblewoman, but with her servant Pierre. The man, ostensibly a peasant, had impeccably refined manners. And his mistress hardly ordered him to do anything for her! The innkeeper talked freely of his suspicions, and soon other people in Granville were watching the two like hawks. When Pierre was finally sent on an errand, to buy candles, townspeople followed him. Nervous, Pierre paid for the candles with a gold coin, and barely bothered to collect his change.

In this paranoid atmosphere, this unusual behavior was enough. Several members of the newly reconstituted National Guard followed Pierre back to his rooms and forced their way in. With guns and sabers drawn, they interrogated the two travelers. But their stories didn’t line up. Suspicion grew to a fever pitch.

France was indeed in an uproar in August 1830, and conspiracy theories were in the air. But in this case the suspicions were entirely correct. The poorly dressed man was not the Marquise de Saint-Fargeau’s manservant. He was Jules de Polignac, former prime minister for the deposed King Charles X, and one of the most hated men in France. He had been just a few hours away from boarding a ship out of the country. Now, he was locked up and headed back to Paris, where the new King Louis-Philippe and his hastily assembled government would have to decide what to do with him.1

France was indeed in an uproar in August 1830, and conspiracy theories were in the air. But in this case the suspicions were entirely correct. The poorly dressed man was not the Marquise de Saint-Fargeau’s manservant. He was Jules de Polignac, former prime minister for the deposed King Charles X, and one of the most hated men in France. He had been just a few hours away from boarding a ship out of the country. Now, he was locked up and headed back to Paris, where the new King Louis-Philippe and his hastily assembled government would have to decide what to do with him.1

Above: Victor Ratier, “Arrestation de Polignac,” circa 1830. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France. A caption accompanying the original image reads: “‘My good friends, when I tell you that I am and have never been anything but a servant!’ ‘—Yes, of Wellington and Company, let’s go! You seem so stupid and so well-bred that you could only be a Polignac.’”

This is The Siècle, Episode 49: The Trial.

Welcome back! This episode has taken a little longer to finish than I hoped, but I think you’ll find it’s worth the wait: a jumbo-sized episode stuffed with dramatic moments, including riots and revolution, murder and machinations. We’re now fully into the July Monarchy, and the action is not going to let up for quite some time.

Before we dive in, I wanted to as always thank the show’s network, Evergreen Podcasts, and all of you who support the show on Patreon. For as little as $1 per month, you can help make this show possible and get an ad-free feed. Since our last episode, new supporters include Sarah Meador, Reza Roodsari, Donald Hughes, Paul Laz, William, Biku, Matthew, OccludedRose, Vincent Vecchione, and Becky and Rob Eggmann. Find out how to join them at thesiecle.com/support.

You can also see a full annotated transcript of this episode at thesiecle.com/episode49.

Now, let’s get back to the story.

Lingering revolution

Paris newspapers reported Polignac’s arrest on August 20, 1830. It was three weeks since the street fighting in Paris had ended, and nine days since Louis-Philippe had been sworn in as the new King of the French. But assembling a functional government in the post-revolutionary chaos was easier said than done.

For one thing, it was far from obvious at the time that Paris was actually post-revolutionary. The revised Constitutional Charter had passed only in the face of aggressive street protests by republican activists, and things had come close to a violent confrontation before both Louis-Philippe and the left-wing leader Lafayette had backed down, as I covered in Episode 47.

Some of this disorder was organic and natural. The July Revolution had been fought spontaneously, under chants praising “the Charter” and “liberty.” But these terms meant different things to different people. Many of the Paris workers who had taken the lead on the barricades believed that the new spirit of liberty meant they could demand economic changes: higher wages, shorter workdays, or a ban on new machines that required fewer workers. On August 15, the same day Polignac was arrested in Granville, around 400 carriage and saddle workers marched through Paris to deliver a petition demanding the expulsion of foreign workers, “in order to make more jobs available for Frenchmen,” and Paris butchers demonstrated for an end to government regulation of their shops. The next day cab drivers protested against the competition from Paris’s recently introduced horse-drawn busses; a few days after that 400 carpenters marched to demand the government increase their wages. On August 23 as many as 5,000 machinists and locksmiths marched to demand an ordinance cutting their workday by an hour.2 We’ll talk more about these workers and their demands in a future episode, but know for now that they were part of a democratic, revolutionary spirit in the streets of Paris.

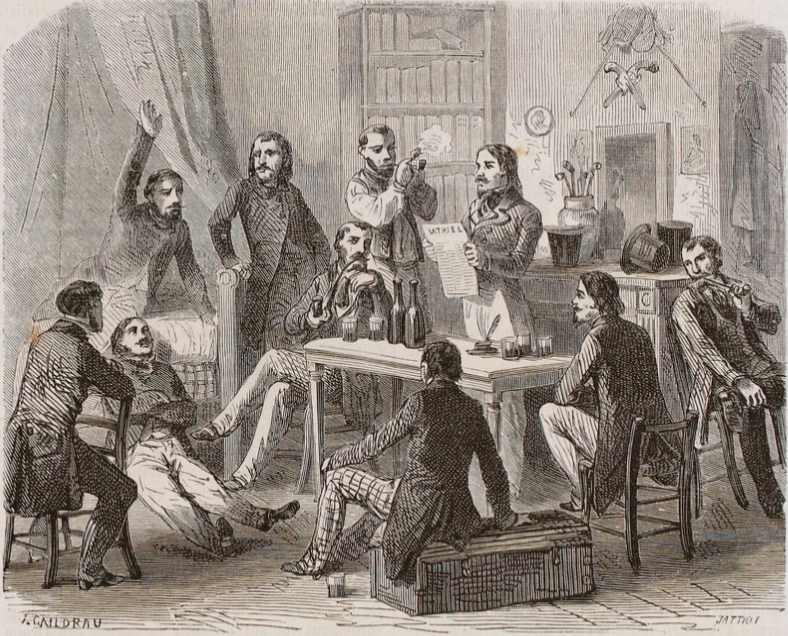

But Paris also featured a range of semi-secret societies and clubs. Some, like the Francs Régenérés, were actively revolutionary and often predominantly composed of students. More prominent was the Société des Amis du Peuple, or Society of the Friends of the People. The Friends of the People met publicly — arguing that France’s law prohibiting unauthorized gatherings of 20 or more people had been nullified by the revolution. It had support from prominent progressive politicians, and organized itself as a pressure group to urge Louis-Philippe and his government in a more progressive direction.3

But Paris also featured a range of semi-secret societies and clubs. Some, like the Francs Régenérés, were actively revolutionary and often predominantly composed of students. More prominent was the Société des Amis du Peuple, or Society of the Friends of the People. The Friends of the People met publicly — arguing that France’s law prohibiting unauthorized gatherings of 20 or more people had been nullified by the revolution. It had support from prominent progressive politicians, and organized itself as a pressure group to urge Louis-Philippe and his government in a more progressive direction.3

Above: Jules Gaildrau, a depiction of a meeting of the Society of the Rights of Man, a successor organization to the Society of the Friends of the People, in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

It was against this backdrop of both spontaneous and organized street protest that Louis-Philippe tried to form his first government. The king’s goal was to form a sort of unity government, one that represented all factions in the victorious rebel coalition. In other words, it was a government whose ministers disagreed with each other about almost everything. Most of them hated each other personally, too.

The Ministry of August 11

The foreign minister was Louis-Mathieu Molé, better known as Comte Molé. Molé had served in government under Napoleon and Louis XVIII, before entering the opposition as the Bourbon Restoration moved to the right. The finance minister, Joseph Dominique, baron Louis, had a similar background: he had been active during the 1789 Revolution, and later served under Napoleon and Louis XVIII. The justice minister, Jacques-Charles Dupont de l’Eure, also had a record of government service dating back to the First Republic.

Two former Napoleonic generals held the military ministries: the Corsican Horace Sébastiani was the naval minister (though he had ambitions of being foreign minister), while Étienne Gérard had the War Ministry.

Two former Napoleonic generals held the military ministries: the Corsican Horace Sébastiani was the naval minister (though he had ambitions of being foreign minister), while Étienne Gérard had the War Ministry.

Right: Laurent Dabos, portrait of Horace Sébastiani, circa 1830-35. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The final two ministries were held by members of the Doctrinaire faction I introduced in Episode 29: The liberal aristocrat Duc Victor de Broglie was the minister of public instruction and religion, while the writer François Guizot was the interior minister.

Louis-Philippe also appointed four “ministers without portfolio,” advisers who would take part in the meetings of the Council of Ministers without actually heading a department. These included the attorney André Dupin, the banker Casimir Périer, the experienced diplomat Louis Pierre Édouard, Baron Bignon, and — last but certainly not least — the banker Jacques Laffitte.

These men ran the gamut in both their politics and temperament. Molé, Broglie, Guizot, and Périer were all on the conservative side — though this wasn’t always obvious to the public, at least at first. Guizot, for example, had a progressive reputation from the years he spent leading liberal electoral campaigns with the “Aide-Toi” group.4 Baron Louis was a conservative, but his duties at the finance ministry were demanding and highly technical, which largely sidelined Louis from the cabinet’s ideological debates. On the other side, Laffitte, Bignon, and Dupont de l’Eure were to varying degrees progressives. In between were Sébastiani, Gérard, and Dupin, who could veer one way or the other depending on the issue.5

These men ran the gamut in both their politics and temperament. Molé, Broglie, Guizot, and Périer were all on the conservative side — though this wasn’t always obvious to the public, at least at first. Guizot, for example, had a progressive reputation from the years he spent leading liberal electoral campaigns with the “Aide-Toi” group.4 Baron Louis was a conservative, but his duties at the finance ministry were demanding and highly technical, which largely sidelined Louis from the cabinet’s ideological debates. On the other side, Laffitte, Bignon, and Dupont de l’Eure were to varying degrees progressives. In between were Sébastiani, Gérard, and Dupin, who could veer one way or the other depending on the issue.5

Left: Victor de Broglie, artist unknown, sometime between 1815 and 1848, possibly early 1830s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

I offer up these political labels as a quick shorthand, but of course these men’s actual political views had considerable nuance, and could vary depending on the issue at hand. Temperament also played a role: Broglie, Guizot, and Périer were all fairly firm in their conservatism, for example, while Molé believed that “a flexible approach” was the best way to attain his conservative aims.6

Compounding these ministers’ political divisions was personal animosity. Laffitte and Périer were both liberal banker-politicians, but the optimistic and outgoing Laffitte and the dour Périer did not get on at all. Guizot had more in common with Périer’s politics, but thought the banker too ambitious. Laffitte in turn thought Guizot was condescending — and Broglie even worse. The blue-blooded Broglie was near-sighted and used a lorgnette — a pair of glasses with a handle. During one debate, as Broglie squinted at Laffitte through these spectacles, Laffitte snapped: “Monsieur le Duc, I beg you not to look at me that way.” Dupin declared himself “the government’s chief spokesman,” to the great annoyance of everyone.7

Compounding these ministers’ political divisions was personal animosity. Laffitte and Périer were both liberal banker-politicians, but the optimistic and outgoing Laffitte and the dour Périer did not get on at all. Guizot had more in common with Périer’s politics, but thought the banker too ambitious. Laffitte in turn thought Guizot was condescending — and Broglie even worse. The blue-blooded Broglie was near-sighted and used a lorgnette — a pair of glasses with a handle. During one debate, as Broglie squinted at Laffitte through these spectacles, Laffitte snapped: “Monsieur le Duc, I beg you not to look at me that way.” Dupin declared himself “the government’s chief spokesman,” to the great annoyance of everyone.7

Right: Unidentified painter, portrait of Jacques Laffitte, 19th Century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

These political and personal divisions were an obvious weakness for the ministry, but they were a weakness Louis-Philippe could live with. With his ministers at loggerheads, that left the king as the leading figure in his own government, able to “maintain his independence by maneuvering between the conflicting groups.”8

Odilon Barrot

There are two other figures worth noting, who were outside of the ministry but held key responsibilities for maintaining order. One is a familiar face: Gilbert du Motier, better known as General Lafayette, the lifelong revolutionary currently commanding the French National Guard. We’ll talk more about Lafayette in a minute. First, though, I wanted to introduce the second figure, a 39-year-old attorney named Odilon Barrot. Barrot has been playing important roles in the background so far, and it’s time to finally bring him to center stage.

There are two other figures worth noting, who were outside of the ministry but held key responsibilities for maintaining order. One is a familiar face: Gilbert du Motier, better known as General Lafayette, the lifelong revolutionary currently commanding the French National Guard. We’ll talk more about Lafayette in a minute. First, though, I wanted to introduce the second figure, a 39-year-old attorney named Odilon Barrot. Barrot has been playing important roles in the background so far, and it’s time to finally bring him to center stage.

Right: Unknown artist, drawing of Odilon Barrot, 19th Century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Barrot was one of the leaders of the “Aide-Toi” electoral committee, alongside Guizot. Barrot was not an elected deputy, but during the July Revolution, he was on hand at the deputies’ meetings in his role as a liberal organizer. They appointed him to be their secretary. Then, when the deputies created the Paris Municipal Commission on July 29, they named him to be its secretary. In that role he was on hand in the Hôtel de Ville during the crucial days after the Revolution, helping to govern Paris. He argued in favor of crowning Louis-Philippe king. In Episode 45 I mentioned how Lafayette had sent a “messenger” to the deputies on July 30, warning them that the people of Paris demanded actual reforms, not merely a change in kings; Barrot was that messenger. In Episode 47 I mentioned how Louis-Philippe had sent envoys to meet with Charles X at the royal hunting lodge of Rambouillet, pressuring him to flee the country. Barrot was one of those envoys. So it’s not surprising that when offices were handed out after the July Revolution, Barrot was given an important one: Prefect of the Seine.9

French prefects are the effective governors of France’s departments, with sweeping executive powers. And the Department of the Seine was the department that included Paris. So Barrot was in effect in charge of day-to-day governance in the capital — a hugely important position. This is especially noteworthy since Barrot was a progressive, a close ally of Lafayette who wanted the July Revolution to bring real change to France.10

Everyone’s favorite fighting Frenchman

Then there is, of course, Lafayette. The old revolutionary had helped place Louis-Philippe on the throne, and he still commanded the National Guard — the largest and most effective military force in Paris.

There were some 50,000 National Guardsmen in Paris. Some of these had been members of the old National Guard, which had had less than 20,000 members when Charles X dissolved it in 1827. But it also included tens of thousands of new recruits. The Guard was envisioned as a bourgeois force, and its members were required to buy their own equipment and uniforms at the expensive rate of around 250 francs — a sum that a Paris workingman might take many months to earn. Amid the patriotic enthusiasm after the July Revolution, though, this requirement was loosened. Hundreds of workers were welcomed into Guard units, with wealthier Guardsmen paying for their uniforms. Weapons were harder to find, and many new Guardsmen simply went without. As late as November 1830, one-quarter of the guardsmen were unarmed.11

These partially armed 50,000 men were tasked with keeping order in Paris. The city still had a police force, but as I discussed in Episode 41, this consisted of little more than 200 men for the whole city. Their patrols required backup. Ordinarily, providing that backup was the job of the gendarmes, the military police, but after the Paris Gendarmerie’s battles with rioters during the July Revolution, they were wildly unpopular. In mid-August, Louis-Philippe’s government cut their losses and disbanded the Paris Gendarmerie altogether. In its place was a new organization, the Municipal Guard, who everyone immediately figured out were basically the old gendarmes with a new name and uniform. This tension made the Municipal Guard unreliable for crowd control and they will be kept back from sensitive situations. Finally, there was the regular army, but in the aftermath of the Three Glorious Days the army refused to patrol the streets of Paris alone. So things fell on the National Guard, who provided 3,700 men each day in a rotation, doing everything from containing riots to collecting tolls at the city limits.12

And in command of this indispensable force was Lafayette, the standard-bearer of the Left. Besides this military power, Lafayette had close ties to the left-wing activists in the Society of the Friends of the People, and also to the king. Louis-Philippe invited Lafayette and his family to dinner repeatedly in this time. The writer Charles de Rémusat, who was married to Lafayette’s granddaughter, described the dinners as “two dynasties at the table,” and notes pointedly that it was not Lafayette’s side which was overflowing with courtesies.13

And in command of this indispensable force was Lafayette, the standard-bearer of the Left. Besides this military power, Lafayette had close ties to the left-wing activists in the Society of the Friends of the People, and also to the king. Louis-Philippe invited Lafayette and his family to dinner repeatedly in this time. The writer Charles de Rémusat, who was married to Lafayette’s granddaughter, described the dinners as “two dynasties at the table,” and notes pointedly that it was not Lafayette’s side which was overflowing with courtesies.13

Left: Unknown artist, engraving of Lafayette after a painting by Alonzo Chappel, 1874. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But Lafayette’s close ties to the king and to Paris’s left-wing activists meant he was caught in between, effectively trying to mediate the fundamental differences between what those two sides wanted. The activists wanted a republic, to be sure, but Lafayette thought they could be satisfied if Louis-Philippe continued to make reforms — to create the “popular monarchy surrounded by republican institutions” that the king had endorsed in his pivotal meeting with Lafayette during the July Revolution. So he pressed Louis-Philippe to continue making liberal reforms — because if the republicans weren’t satisfied, there might soon be another revolution. “I know only one man who can now bring France to a republic, and you are that man,” Lafayette told the king.14

The old revolutionary was sincere in his belief that Louis-Philippe could be a partner in reform. He called the king “ a good citizen” and “a true patriot of [17]89.” Lafayette wasn’t blind to the fact that many French politicians were opposed to the “republican institutions” he thought necessary, including some of the king’s advisers. But he didn’t think the king was part of that conservative camp. “I prefer the king to his ministers, and I prefer the ministers to the Chamber [of Deputies],” Lafayette told Rémusat one day. Rémusat thought his grandfather-in-law was making a mistake to trust in the power of any king — even Louis-Philippe: “The worst Chamber was more liberal than the best king,” Rémusat replied. But Lafayette thought he had influence over Louis-Philippe that could bring about his desired reforms.15

Federation

Below: Joseph-Désiré Court, “The King Distributing Battalion Standards to the National Guard,” 1836. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. This 1836 painting makes some key changes from the actual event. Most notably, it shows King Louis-Philippe personally handing flags to the guardsmen, while the commander of the National Guard, Lafayette, is tucked away in the background. In the real ceremony, the king handed the flags to Lafayette, who then handed them to the guards. “Had Lafayette still been alive in 1836 when Court’s work was exhibited at the Salon, the scene would have outraged him,” wrote art historian Albert Boime.16

On August 29, 1830, all 50,000 National Guardsmen assembled on the Champ de Mars, a large field on the Left Bank of the Seine. The guardsmen paraded before what one source claims was 300,000 cheering spectators, and King Louis-Philippe handed Lafayette official tricolor flags to distribute to each legion of the Guard. It was a stirring spectacle — not least because the the stability of Louis-Philippe’s reign depended on the loyalty of these guardsmen who were cheering him so enthusiastically.17

On August 29, 1830, all 50,000 National Guardsmen assembled on the Champ de Mars, a large field on the Left Bank of the Seine. The guardsmen paraded before what one source claims was 300,000 cheering spectators, and King Louis-Philippe handed Lafayette official tricolor flags to distribute to each legion of the Guard. It was a stirring spectacle — not least because the the stability of Louis-Philippe’s reign depended on the loyalty of these guardsmen who were cheering him so enthusiastically.17

But the spectacle was particularly meaningful to the two men distributing the flags. This very same Champ de Mars had hosted another gathering 40 years earlier: the 1790 Festival of the Federation. Despite a steady rain, 100,000 Parisians had gathered to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the fall of the Bastille, and the new, completely harmonious constitutional monarchy France had created over the prior year. There was a Catholic mass led by the Bishop of Autun — a fellow named Talleyrand — while the commander of the Paris National Guard — a certain Marquis de Lafayette — led lawmakers in swearing an oath to France’s new constitution. Then Louis XVI swore a similar oath, promising to maintain the constitution using his powers as “King of the French.” A young liberal aristocrat, the Duc de Chartres, watched the proceedings with pleasure; among the lawmakers swearing the oath was his father Philippe, the sitting Duc d’Orléans.

This festive mood of summer 1790 wouldn’t last. Within just a few years, war and executions and infighting would tear apart all the leaders who had celebrated the federation in July 1790 apart. Many ended their lives under the guillotine. But 40 years later, one of its surviving participants reminisced fondly to the other: “A witness to the Federation of 1790, in this same Champ de Mars… I assure you that what I have just witnessed, is infinitely superior to what I then considered so complete,” Louis-Philippe wrote in a letter to Lafayette.18

“Who,” wrote Lafayette’s aide Bernard Sarrans, “on reading [these] documents, would not believe that an indissoluble alliance had been formed between Louis-Philippe and Lafayette?”19

Etienne Dubois, “August 29, 1830: Review of the Paris National Guard; Distribution of Flags,” after 1830. Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

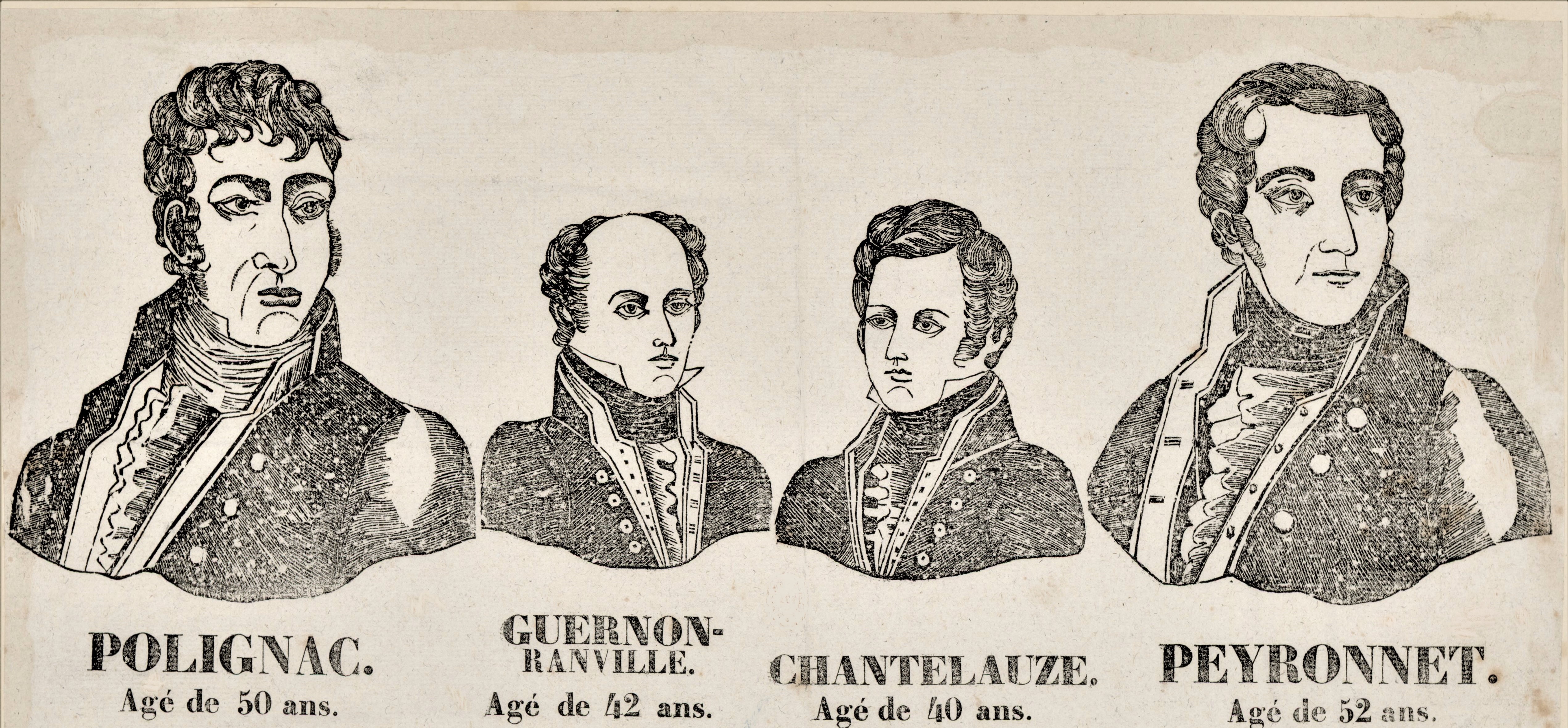

Charles’s ministers

While the National Guard paraded on the Champ de Mars, Jules de Polignac was cooling his heels in the prison fortress of Vincennes, seven miles or 11 kilometers to the east. Polignac was not, at least, alone. The prison also held three of his former colleagues: former justice minister Jean de Chantelauze, former education minister Martial de Guernon-Ranville, and former interior minister Pierre-Denis de Peyronnet.

Right: Selbymay, keep of the castle of Vincennes, February 21, 2012. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license via Wikimedia Commons.

The ministers had been with Charles in Versailles on July 31 when they were told they should look to their own safety. The ministers were given 6,000 francs and blank passports, and set off by whatever means they could find. It was every man for himself. Some of managed to find carriages; others hitched rides in the back of carts, or even walked across country. Several of the ministers wrote down the stories of their escapes, full of twists and turns and high drama. It would derail this episode too much if I were to go into any detail about these attempted escapes; suffice it to say that some of them got lucky and ran into friends who helped them escape, while others were unlucky and ran into mobs of suspicious revolutionaries.20 If you’re interested in learning more about these adventures, let me know and I can cover them in a bonus episode.

For now, we’ll pick things up with Polignac, Chantelauze, Guernon-Ranville, and Peyronnet behind bars at Vincennes. The stout stone walls of the fortress served two purposes: keeping the prisoners in, and keeping mobs of angry Parisians out. During the July Revolution, one of the most popular chants on the barricades had been “Death to the Ministers” — and many of the revolutionaries meant it. But Louis-Philippe’s government wasn’t on board. They had rather hoped that Charles’s ministers would all make it safely out of the country, freeing the new government of having to deal with them.21

You might be reminded of the situation after Waterloo, when the restored Bourbons had issued arrest warrants for prominent Bonapartists like Marshal Michel Ney — but then twiddled their thumbs in the hopes that the fugitives would make their escapes. When Ney and a few others were captured, though, the Bourbons didn’t flinch. They put the men on trial for treason, secured death sentences, and executed them as examples for what lay in store for traitors. I covered this in Episode 5.

That’s not what Louis-Philippe and his advisers had in mind. They were trying to calm things down, both domestically and internationally. That meant being lenient and moderate with political opponents. Executions could “invite bloodshed” and “embroil the government with the courts of Europe.” So if the July Monarchy had to put the ministers on trial, its leaders wanted prison sentences, not death sentences.22

Excerpt from a handbill published shortly after the end of the four ex-ministers’ trial in late December, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Death to the Ministers

This position proved… unpopular, to say the least. Paris simmered in September, while a committee of deputies drafted formal treason charges. The ministers were accused of abuse of power for their attempts at vote-rigging; they were charged with “arbitrarily and violently changing the institutions of the kingdom,” and with having “incited civil war” by “encouraging citizens to arm themselves against one another.” The Chamber of Deputies overwhelmingly approved the indictments, not just against Polignac, Chantelauze, Peyronnet and Guernon-Ranville, but also in abstentia against the three ministers who had successfully escaped France: the naval minister Charles Lemercier de Longpré, better known as Baron d’Haussez; the minister of public works Guillaume Capelle, and the finance minister Guillaume-Isidore de Montbel.23

But things really got heated in October. On October 8, the Chamber of Deputies approved a resolution in favor of abolishing the death penalty for political crimes — crimes such as Charles’s ministers were facing. When this resolution was presented to Louis-Philippe the next day, he endorsed it and promised to propose a law to that effect. It was obvious to anyone paying attention that the fix was in — the powers-that-be were trying to spare the lives of Polignac and company.24

For a week leading up to the October 8 vote, police had reported increasingly violent sentiment, including signs and public comments calling for “Death to the Ministers.” After October 8, things exploded. On October 9 a National Guard unit nearly opened fire on an angry crowd of protesters against curtailing the death penalty. More signs calling for death to the ministers went up, faster than police could take them down. Some even contained threats against the Chamber of Peers, which would be the judges in the ministers’ trial, such as one sign reading: “Death to the Ministers. We consider as accomplices in high treason every individual who attempts to save them from the punishment that our fathers, our brothers killed on July 27, 28, and 29, 1830, demand.”25

For a week leading up to the October 8 vote, police had reported increasingly violent sentiment, including signs and public comments calling for “Death to the Ministers.” After October 8, things exploded. On October 9 a National Guard unit nearly opened fire on an angry crowd of protesters against curtailing the death penalty. More signs calling for death to the ministers went up, faster than police could take them down. Some even contained threats against the Chamber of Peers, which would be the judges in the ministers’ trial, such as one sign reading: “Death to the Ministers. We consider as accomplices in high treason every individual who attempts to save them from the punishment that our fathers, our brothers killed on July 27, 28, and 29, 1830, demand.”25

On October 17, Louis-Philippe returned to Paris to find his home, the Palais-Royal, “almost besieged” by a crowd chanting for the ministers’ heads. When guards evicted the protesters from the Palais-Royal, several hundred marched on the Palais Luxembourg, where the Chamber of Peers met, and tried unsuccessfully to break down the gate. The next day, October 18, crowds grew bigger and more boisterous. Some chanted, “Death to the old ministers, or the head of Louis-Philippe.” Evicted from the Palais-Royal again, the crowd turned and marched southeast with an ominous new chant: “To Vincennes!” Convinced that the legal system would spare the traitorous ministers, a mob was headed off to kill the men themselves.26

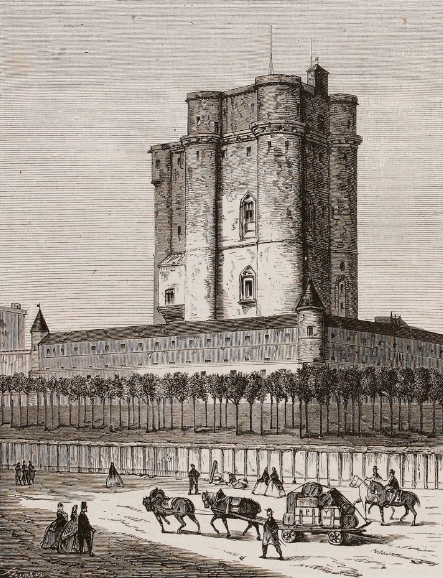

Above: Unknown artist, the castle of Vincennes, in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The mob

Et l’Émeute paraît, l’Émeute au pied rebelle

Poussant avec la main le peuple devant elle;

L’Émeute aux mille fronts, aux cris tumultueux

Grossit à chaque bond ses rangs impétueux

Et le long des grands quais où son flot se déroule

Hurle en battant les murs comme une femme soûle.

And the Riot appears, Riot with defiant tread,

With a shove of its hand driving the people ahead;

Riot with a thousand faces, shouting in uproar,

Swelling its fierce ranks with each leap, ever more,

Along the great quays where its surging tide rolls,

It pounds at the walls like a drunken woman punching holes.

— Auguste Barbier, “L’Émeute (The Riot),” 1831. English translation by Emmanuel Dubois of the La Fayette, We Are Here! podcast.

What you just heard is part of a poem written during this chaotic period, by Auguste Barbier. My thanks to Emmanuel Dubois of the Lafayette, We Are Here! podcast for reading the poem, and for translating it into English.

Barbier was far from the only one alarmed at the civil unrest in Paris in these turbulent months. Sentiments like this were common across French leaders, from radicals to progressives to conservatives. We don’t have accounts from any of the people who participated in this lynch mob, but even radical newspapers distanced themselves from it, like the republican Tribune des Départmens. The Tribune was sympathetic, writing how the “apparent cause of this movement is the fear of seeing men who have shed the blood of citizens acquitted; the real cause is general discontent.” But it condemned unnamed groups who it said were “taking advantage” of this discontent “to stir up the masses.”27 The new worker-run Journal des Ouvriers, or “Newspaper of the Workers,” also condemned the October 18 riot and blamed outside agitators: “Most of these brave artisans have refused to participate in these shameful maneuvers. However, some, misled by Jesuitical promises, have had the weakness to sow seeds of unrest in various districts of the capital,” the paper wrote.28 (There is no evidence for these claims of Jesuit agitators.)

Louis-Philippe’s own government was divided over the proper response to this unrest. For conservatives, the watchword was “public order,” which they wanted to secure by deploying the security forces to put down riots and disruptive protests. Progressives, on the other hand, were sympathetic to Parisians coming together to express political opinions in the streets — even if they thought they got a little out of hand. So these progressives wanted to appease the crowd, to make concessions that signaled that the government was on their side and that there was no need for citizens to take the law into their own hands.29

This split played out in emergency cabinet meetings on October 18, as the mob was en route to Vincennes. Everyone agreed that a stern response was called for, and nearby army units were activated to help defend the prison. But Odilon Barrot, the progressive prefect of the Seine, took the initiative of releasing a statement aimed at calming things down. Barrot appealed for peace, he promised that justice would be done to the ministers — and he called the Chamber of Deputies’ vote to abolish the death penalty for political crimes “ill-timed.”30

The Pegleg

Below: Gaston Mélingue, “Le général Daumesnil refuse de livrer Vincennes,” 1882. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The actual lynch mob itself ended up being less important than what it set in motion. Around 11 p.m. on October 18, up to 900 angry Parisians arrived outside the suburban castle of Vincennes, armed with a few muskets, a few swords, and lots of clubs and sticks. The crowd demanded that the castle’s governor turn over his prisoners to them. But the mob had miscalculated. The governor of Vincennes came out of his gates to meet them, hobbling on a wooden leg. His name was General Pierre Daumesnil, a decorated Napoleonic veteran who had previously defended Vincennes against actual invading armies. In spring of 1814, Paris had been beset by the combined Russian, Prussian and Austrian armies, who had demanded that Daumesnil surrender the valuable fortress. He defiantly replied: “The Austrians took one of my legs. Let them return it, or come take the other.” Sixteen years later, the man nicknamed “The Pegleg of Vincennes”31 was not about to give in to a mere mob. If the crowd wanted the prisoners so badly, Daumesnil told them, they were welcome to try. But even if the mob forced its way in, he said, he would personally ignite the castle’s gunpowder reserves and blow them all to kingdom come.32

The actual lynch mob itself ended up being less important than what it set in motion. Around 11 p.m. on October 18, up to 900 angry Parisians arrived outside the suburban castle of Vincennes, armed with a few muskets, a few swords, and lots of clubs and sticks. The crowd demanded that the castle’s governor turn over his prisoners to them. But the mob had miscalculated. The governor of Vincennes came out of his gates to meet them, hobbling on a wooden leg. His name was General Pierre Daumesnil, a decorated Napoleonic veteran who had previously defended Vincennes against actual invading armies. In spring of 1814, Paris had been beset by the combined Russian, Prussian and Austrian armies, who had demanded that Daumesnil surrender the valuable fortress. He defiantly replied: “The Austrians took one of my legs. Let them return it, or come take the other.” Sixteen years later, the man nicknamed “The Pegleg of Vincennes”31 was not about to give in to a mere mob. If the crowd wanted the prisoners so badly, Daumesnil told them, they were welcome to try. But even if the mob forced its way in, he said, he would personally ignite the castle’s gunpowder reserves and blow them all to kingdom come.32

That threat took some of the ardor out of the crowd, who apparently didn’t want to kill Charles’s ministers quite that badly. The mob turned around and marched back to Paris, where many of them ended up arrested outside the Palais-Royal.33

But the conservatives in the government were furious — with Barrot, who had broken with government policy by criticizing the death penalty change. Guizot, who as interior minister was Barrot’s boss, wanted to fire him, and Barrot offered to resign. But the progressive justice minister, Dupont de l’Eure, pushed back. Guizot and Broglie then offered to resign themselves. After some back and forth, Louis-Philippe accepted their resignations. The first government of the July Monarchy was effectively dead, less than three months after being born.34

What followed then was a series of chaotic negotiations as Louis-Philippe tried to find a collection of ministers who could work together. When the dust settled, the king ended up asking Jacques Laffitte to form a government.

Laffitte, the wealthy and popular banker who had done as much as anyone to put Louis-Philippe on the throne, might seem like an obvious choice. But Laffitte was a progressive, and the conservatives in the old government largely refused to serve under him — despite Louis-Philippe’s personal appeals. Molé, Dupin, Baron Louis, and Périer all followed Guizot and Broglie in resigning. Laffitte brought in new men to replace them, and inaugurated his new ministry on November 2.35

But there was, perhaps, more reason than Laffitte’s popularity and Orléanist convictions that made him prime minister. Infamously, the Duc de Broglie had a conversation with Louis-Philippe after resigning in which he told the king to appoint Laffitte — because he would be doomed to fail. “You will be obliged, sooner or later… to submit to the party of progress,” Broglie said. “The sooner the better… In the present state of affairs, M. Laffitte and M. Dupont de l’Eure will not remain in office two months if they intend governing as they wish.” After the inevitable collapse of this progressive ministry, the duke said, Louis-Philippe could appoint loyal conservatives to govern with a firm hand.36

What we don’t know is to what degree Louis-Philippe agreed with this argument. Certainly he was not as committed to this Machiavellian strategy as was the Duc de Broglie. But it’s also plausible that Louis-Philippe was genuinely supportive of Laffitte. Against the conservative advice of Broglie, the king had the progressive advice of his sister Adelaide, who thought it was best to make common cause with the Left. She wrote a letter to Gérard in November expressing joy over the king having dinners with Laffitte, Barrot, and other leading progressives: “I don’t need to tell you that I think this is a very good thing, and that I’m very happy about it,” she wrote. Adelaide distrusted Guizot and Périer, who she thought had been shamefully late in discarding Charles during the July Revolution. They were, as she put it, not very “July.” In contrast, she felt the center-left could be relied upon to support the July Monarchy if push came to shove.37

Regardless of whether the king supported him honestly or deceptively, though, it was Jacques Laffitte who was in charge of France as November turned into December, and the long-awaited trial of the ministers arrived.

Murder most foul?

Before we get to that, I should briefly note several other hugely consequential events that were happening in the fall of 1830. We’ll deal with these events in more detail in future episodes, but it’s important to know that other things were going on at the same time. There was the nitty-gritty work of putting Paris back together after the chaos of the Three Glorious Days. Committees were created to process thousands of requests for compensation from the government: from revolutionaries who had sacrificed on the barricades, from shopkeepers whose stores had been looted, and even from a barber asking to be reimbursed for free shaves he had offered to wounded combatants.38

More scandalously, there was the death on August 30 of the king’s relative, the Duc de Bourbon. That this duke should die was not especially surprising: he was 74 years old. But the circumstances of the old man’s death were anything but normal.

As a warning, this next section will address topics of self-harm. Skip ahead 30 seconds to avoid this.

The duke was found dead in his chambers, with a rope around his neck, but his feet on the ground. It was officially ruled a suicide, but immediately rumors began that this was a cover-up. There were not one but two alternative explanations to be found amid the gossip. One was that the Duc de Bourbon had died by accident, cutting off his own breath as part of an amorous encounter that got out of hand.39

The duke was found dead in his chambers, with a rope around his neck, but his feet on the ground. It was officially ruled a suicide, but immediately rumors began that this was a cover-up. There were not one but two alternative explanations to be found amid the gossip. One was that the Duc de Bourbon had died by accident, cutting off his own breath as part of an amorous encounter that got out of hand.39

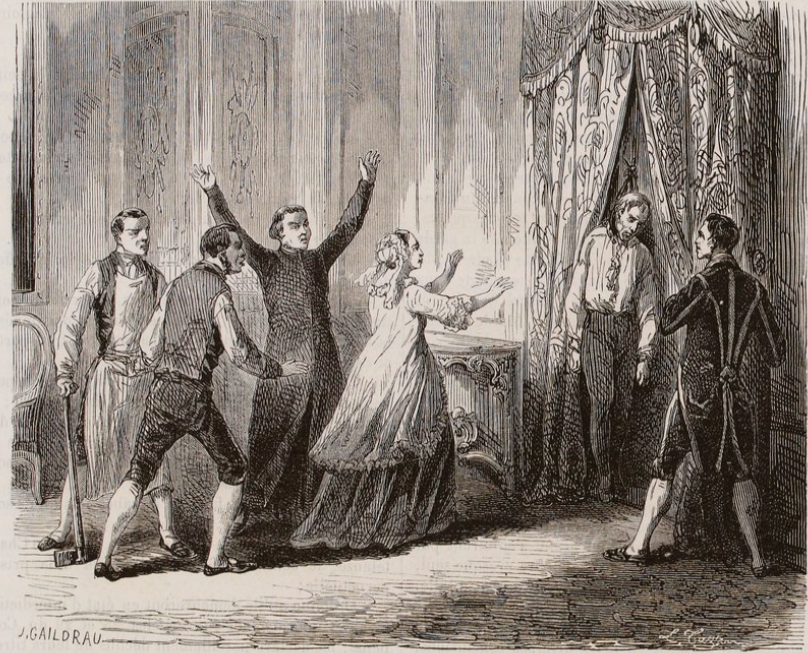

Jules Gaildrau, “Death of the Prince of Condé,” in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The other alternative explanation for the duke’s death was that he had been murdered. Now who, you might ask, would want to kill an eccentric old aristocrat? The answer lies in the fact that the Duc de Bourbon was a really rich old aristocrat — and one without an obvious heir. His son had been the famous Duc d’Enghien, who Napoleon controversially executed in 1804. That meant the Duc de Bourbon’s fortune could go to wherever he willed it — and it just so happened that in 1829 the duke had willed his fortune to Louis-Philippe’s younger son, Henri, the Duc d’Aumale. The inheritance had been arranged by “one of the most despised women in Paris”: the Duc de Bourbon’s longtime mistress, Madame de Feuchères. Born Sophie Dawes, Madame de Feuchères had two huge strikes against her in the eyes of Parisian society: she was English, and she was the daughter of a fisherman. The deal she apparently struck was that she would persuade the Duc de Bourbon to will his fortune to Aumale in return for the Orléans family getting Charles X to receive her at court. Perhaps, rumors swirled, the Duc de Bourbon had been reconsidering this arrangement — and his mistress offed him before he could change his mind.40

No legal consequences came of the Duc de Bourbon’s tragic death. But it affixed a kind of tawdry scandal to the Orléans family just as they were getting started as France’s royal family.

Belgium

Finally, and most important of all: one month after France’s July Revolution, their neighbors to north followed suit by launching the Belgian Revolution.

What we today know as the country of Belgium was, during the 1820s, part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. This was set up by the Congress of Vienna as a mid-sized power to help hem in France. I talked about that in Episode 17. But the Belgians and Dutch had been separate peoples for centuries. The Belgians were mostly Catholic, and the Dutch were mostly Protestant. Some of the Belgians spoke a dialect of Dutch, but many others spoke French.

None of these factors necessarily prevented a union of the two Low Countries, but the Dutch King William (or Willem) I ruled his southern provinces with a heavy hand. Belgian Catholics had to pay higher taxes and support Protestant schools, while being denied a full role in government.41 The simmering discontent in Belgium had been no secret — in fact, one reason Marshal Marmont had so few soldiers in Paris to put down the July Revolution was that Polignac knew a Belgian revolution was possible and had moved several units of French soldiers up to the border, just in case. Polignac’s intelligence about affairs in his own capital may have been lacking, but he was spot-on about the Belgians.42

The trigger for the Belgian revolt — or at least the trigger that would go down in the new national mythology — was an opera performance on August 25, exactly one month after Charles signed the Four Ordinances. The opera was about an Italian revolt in the 1600s, and when the duet “Amour sacré de la patrie,” or “Sacred love of the Fatherland,” was sung in the second act, the audience erupted. Crowds surged out into the streets and began rioting against the Dutch. They were joined by local artisans, and soon reinforced by defections from middle-class militia companies. Government forces were unable to restore order. William was asked to make concessions to end the uprising, but refused to commit to anything significant. Instead, he sent in the army. But the inexperienced Dutch soldiers came up against the same things that had stymied Marmont’s men: urban fighting at street barricades. They fared no better and retreated. A congress of Belgian leaders met and declared independence on October 4, 1830.43

The trigger for the Belgian revolt — or at least the trigger that would go down in the new national mythology — was an opera performance on August 25, exactly one month after Charles signed the Four Ordinances. The opera was about an Italian revolt in the 1600s, and when the duet “Amour sacré de la patrie,” or “Sacred love of the Fatherland,” was sung in the second act, the audience erupted. Crowds surged out into the streets and began rioting against the Dutch. They were joined by local artisans, and soon reinforced by defections from middle-class militia companies. Government forces were unable to restore order. William was asked to make concessions to end the uprising, but refused to commit to anything significant. Instead, he sent in the army. But the inexperienced Dutch soldiers came up against the same things that had stymied Marmont’s men: urban fighting at street barricades. They fared no better and retreated. A congress of Belgian leaders met and declared independence on October 4, 1830.43

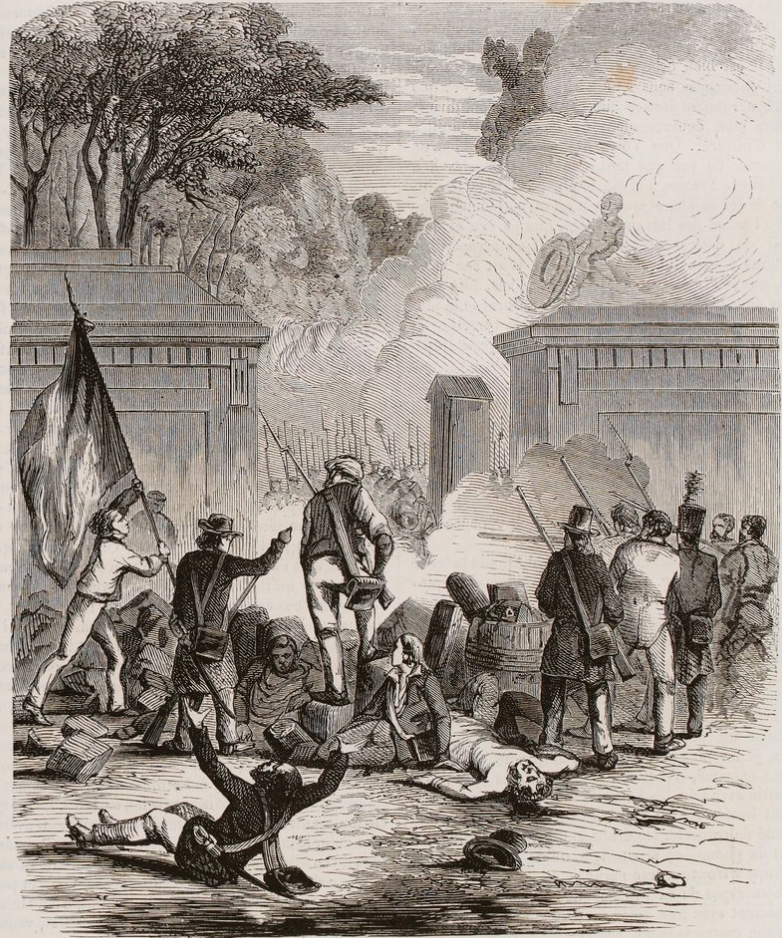

Above: Artist unknown, depiction of the Belgian Revolution, in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

This rebellion was obviously of massive importance for the Belgians, and for the Dutch. But it also mattered for everyone else, because in the fall of 1830 the Belgian crisis pushed Europe to the brink of a new war between the great powers.

Many people in France wanted Belgium to be part of France — as it had been for 20 years under the First Republic and the Empire. Annexing Belgium again would push France’s northern border to the Rhine river, a defensible frontier that French nationalists saw as France’s “natural borders.” Less aggressively, they could simply annex the southern, French-speaking part. Left to its own devices, France could easily sweep away the small and inexperienced Dutch army. But France would not be left to its own devices. The other great powers of Europe — Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria — were all determined to prevent a return to French expansionism, to keep it locked within the borders set at the Congress of Vienna. If France tried to annex Belgium — or even to bring Belgium into its sphere of influence as a protectorate — it could provoke a new round of warfare, just 15 years after Europe’s armies had clashed on Belgian soil at the Battle of Waterloo.44

But France wasn’t the only country threatening to send its armies in to Belgium. On the other side of the equation were the conservative powers of Russia and especially Prussia. These countries had been alarmed by the revolution in France, but had ultimately decided against declaring war over it. But the Belgians were both much smaller than France, and represented an escalation — not just a revolution in one country, but revolution spreading from country to country. In 1820, Russia, Prussia, and Austria had met at a conference in the city of Troppau and issued the “Troppau Protocol,” which read:

States, which have undergone a change of government due to revolution, the result of which threaten other states, ipso facto cease to be members of the European Alliance, and remain excluded from it until their situation gives guarantees for legal order and stability. If, owing to such alterations, immediate danger threatens other states the powers bind themselves, by peaceful means, or if need be, by arms, to bring back the guilty state into the bosom of the Great Alliance.

I covered this in Episode 18.

Under that doctrine, the Austrians had sent in an army to crush Italian revolts after 1820. And a decade later, the Prussians massed an army corps on the Dutch border and prepared to intervene and crush the Belgians.

But just as the other powers of Europe saw French intervention in Belgium as a threat to their interests, France saw its rivals invading Belgium as a threat to its interests. Louis-Philippe was still not completely secure on his throne, and the last thing he wanted was a Prussian army sitting on his northern border that might be tempted to just keep marching south towards Paris — killing two revolutions with one stone. So on August 31, 1830, Comte Molé summoned the Prussian ambassador and told him that while Louis-Philippe did not intend to interfere in Belgium, they would not tolerate Prussia interfering either. If Prussian soldiers entered Belgium, Molé said, French troops would immediately invade to expel them.45

The Prussians backed down — for now. But the saber-rattling was far from over, and diplomats criss-crossed Europe trying to line up coalitions: would the Russians and Austrians back the Prussians up? Could France somehow get British support in the dispute? We’ll return to see how all this plays out in a future episode — one that will feature the return to center stage of one of the most notorious men of the age: Talleyrand.

Égide Charles Gustave Wappers, “Episode of the September Days, 1830, on the Grand Place of Brussels,” 1835. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Jury of Peers

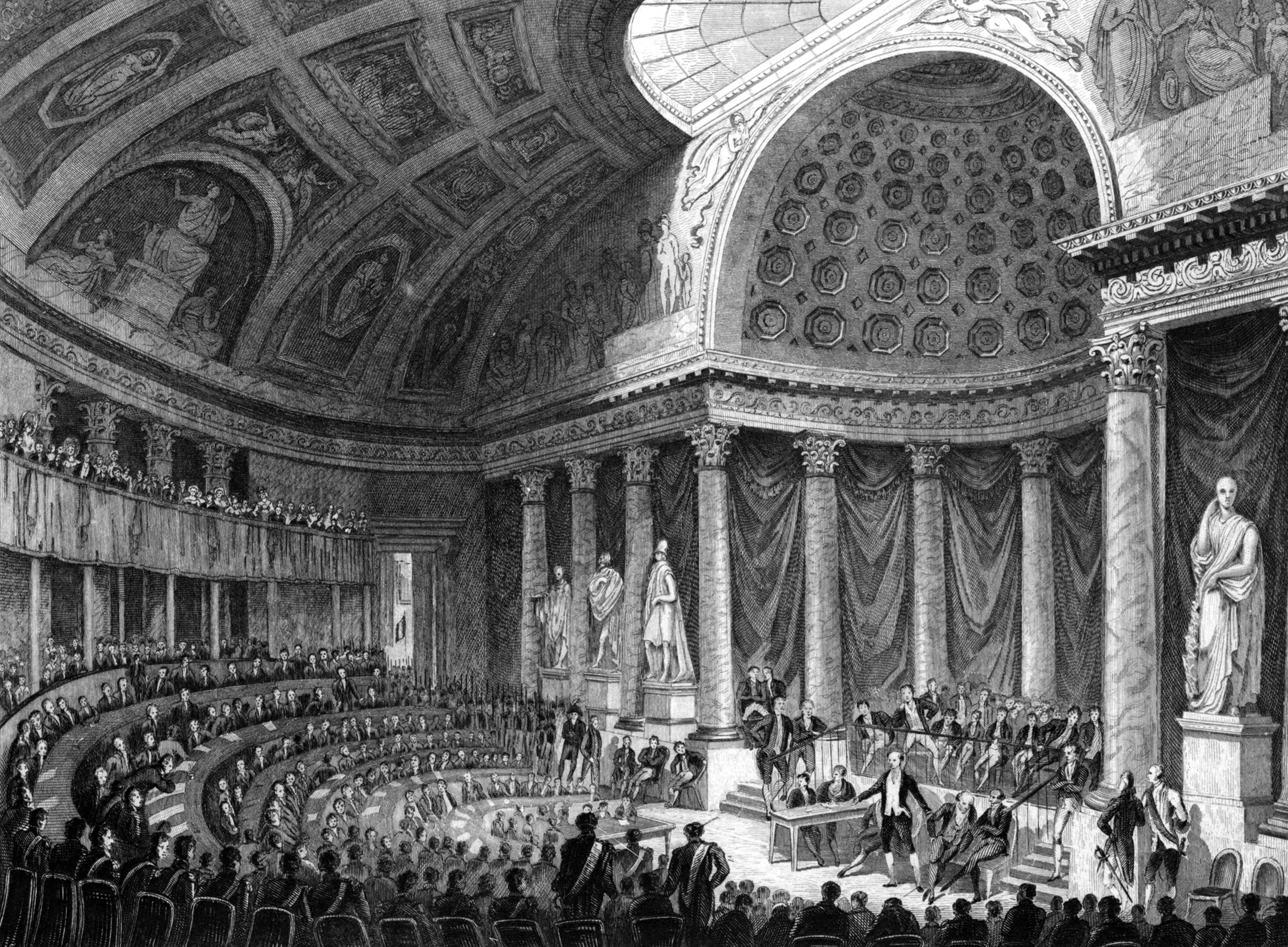

The treason trial of Charles X’s ministers began on December 15, 1830, in the Chamber of Peers. Despite the politically heightened nature of the charges, this was not going to be a quick-and-dirty affair. The Peers followed normal legal procedure over a multi-day trial. First were several days in which Polignac, Peyronnet, Chantelauze, and Guernon-Ranville were brought to the stand and interrogated. The legal arguments did not begin until the fourth day, Saturday the 18th, when one of the deputies serving as a prosecutor laid out the case why the Four Ordinances had constituted treason. After that it was the defendants’ turn. Each of the four ministers had their own separate attorneys, making separate speeches and separate arguments. But I’ll focus on Polignac’s defense, in part because of his highly unusual lawyer: Jean-Baptiste Gay, Viscount de Martignac. This is the man who had been de facto prime minister before Polignac — who Charles had fired in favor of Polignac.46 (I covered Martignac’s ministry in Episode 33.)

Fenner Sears, the December 1830 trial of the ex-ministers in the Chamber of Peers, 1831. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Showing no ill-will, Martignac turned down an offered payment of 100,000 francs and presented a robust pro bono defense of his onetime rival.47 Martignac argued that as a legal matter, the charges against his client were invalid. But, he acknowledged, the Chamber of Peers was not simply a court; it was a political body charged with considering the bigger picture. So Martignac continued to rebut each of the charges against his client. Polignac was charged with election manipulation; with personal experience Martignac argued that what Polignac had done was simply standard procedure for Restoration ministries of all stripes. He was charged with plotting civil war; this was absurd since Polignac had expected no resistance to the ordinances. Invoking Article 14 of the Charter was not illegal, if only because the old wording of that article letting the king make “the necessary regulations and ordinances for the execution of the laws and the security of the state” was extremely broad. Finally, Martignac closed with a plea that if the Peers convicted Polignac anyway, they could not — and should not — impose the death penalty: “The blood that you would shed today, do you think that it would be the last?” Martignac said. “In politics, as in religion, martyrdom breeds fanaticism and fanaticism in its turn breeds martyrdom.”48

The other ministers all had their own attorneys and their own speeches. Peyronnet’s attorney argued that the Four Ordinances had been legal. Chauntelauze’s lawyer avoided such specifics in favor of a plea for “mercy and French unity.” Guernon-Ranville’s attorney Adolphe Crémieux dramatically passed out midway through his speech; as he was carried out of the room, his legal robes fell away to reveal his National Guard uniform underneath.49 Crémieux had come ready for action. Because the real drama of the trial of the ministers was not in the Peers’ courtroom. It was out on the streets.50

“Gouët,” seating chart for the Chamber of Peers during the trial of Charles X’s former ministers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Preparations

After the attempted lynching of October 18, Louis-Philippe’s government was all too aware of the potential for popular violence surrounding the trial of the ministers. Aside from the strong feelings that Polignac inspired and the lingering spirit of unrest after the revolution, Paris in the fall of 1830 was in the middle of an economic crisis. Unemployment was high. The government offered work-relief programs, but they provided for only 3,000 workers — when thousands more remained unemployed.51

But the potential for riots wasn’t what kept Jacques Laffitte up at night. No, the real worry was about the men in charge of quelling any riots. Because the prevailing sentiment among the citizens of Paris wanted Charles’s ministers executed — and under the July Monarchy, the defense of Paris was in the hands of Paris’s citizens. Could the National Guard be relied upon in a crunch?

Police officials were convinced the answer was “no.” One report on the eve of the trial found unanimous agreement from the city’s police commissioners that “the National Guard could not be counted on to offer any real resistance to popular action directed against the former ministers.” Or worse: that many of the Guardsmen might actually join in an attempt to kill Charles’s ministers.52 But what other choice did Louis-Philippe and Laffitte have?

On the other hand, Lafayette insisted that the National Guard would do its duty — and was offended by suggestions that it wasn’t reliable. Besides, Lafayette was in touch with leaders of left-wing groups. He had issued praise and promises to them, including the suggestion that the best way to win progressive concessions from Louis-Philippe was by demonstrating the left’s loyalty instead of its danger. Everything was under control.53

Not that even Lafayette thought things were calm! His letters and proclamations from this period refer to a “crisis” and to the presence on the streets of Paris of “violence and anarchy.” But as he told the National Guard in his Order of the Day for December 19, he had unshakable confidence “in the Parisian population, in the brave and generous Victors of July,” and “in his dear brothers-in-arms of the National Guard.” Lafayette’s order also sought to assure any of his men who might have been tempted by leftist agitation that Louis-Philippe’s government was still progressive: “A popular throne surrounded by republican institutions: such was the program adopted at the Hôtel de Ville by a patriot of [1789] turned Citizen-King; the people and the King will prove faithful to this contract.”54

Despite Lafayette’s confidence, and despite his protests, Laffitte’s government moved thousands of regular soldiers into Paris to support the National Guard. These soldiers, as it happened, were commanded by an old friend of Lafayette’s: General Charles Fabvier. Fabvier had been a Napoleonic soldier and aide to Marshal Marmont, before becoming a devoted participant in liberal conspiracies like the Carbonari. On this show, we last saw Fabvier in Episode 30, fighting in the Greek War of Independence. After the July Revolution, Fabvier had been restored to active duty and granted command of the military district of Paris. His presence helped soften Lafayette’s concerns about bringing in the soldiers. So, too, did the fact that Lafayette remained in overall command of both Guardsmen and soldiers.55

Despite Lafayette’s confidence, and despite his protests, Laffitte’s government moved thousands of regular soldiers into Paris to support the National Guard. These soldiers, as it happened, were commanded by an old friend of Lafayette’s: General Charles Fabvier. Fabvier had been a Napoleonic soldier and aide to Marshal Marmont, before becoming a devoted participant in liberal conspiracies like the Carbonari. On this show, we last saw Fabvier in Episode 30, fighting in the Greek War of Independence. After the July Revolution, Fabvier had been restored to active duty and granted command of the military district of Paris. His presence helped soften Lafayette’s concerns about bringing in the soldiers. So, too, did the fact that Lafayette remained in overall command of both Guardsmen and soldiers.55

Left: Jules Pelcoq, drawing of Charles Fabvier, in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

I’ll also note that in contrast to Polignac’s decision-making five months prior, Laffitte’s government also mobilized soldiers from around Paris and moved them into position near the capital — just in case they were needed.56

Confrontation

All this preparation did not seem immediately necessary when the trial began on December 15. A crowd thronged around the Luxembourg Palace, where the Peers met and where the accused ministers had been temporarily relocated. But no disorder broke out, either on the streets or in the galleries inside the palace, where tickets were required for admission. Things remained peaceful for the next several days, as the accused were interrogated, and then as Martignac launched his defense of Polignac. But on the fifth day, with the trial nearing its final stages, things began to get more uneasy. Peers leaving the Luxembourg Palace reported “ominous gatherings” in the streets. Police spies reported plots by left-wing agitators to attack the Chamber of Peers. The fact that further inquiries suggested that none of these leftist conspiracies were close to striking didn’t lift the tension — there were other alarming reports. Allegedly a group of Bourbon loyalists were about to raise the flag of rebellion in the name of Charles X’s grandson Henry. Or perhaps republicans were about to proclaim a new Committee of Public Safety. Or perhaps there was a Bonapartist army on France’s borders, ready to put Napoleon’s son on the throne.57

The next day, December 20, saw the end of Chantelauze’s defense, and then Adolphe Crémieux speaking on behalf of Guernon-Ranville before passing out. But as the speeches went on, people in the galleries began to send notes to the president of the Chamber of Peers, Baron Étienne-Denis de Pasquier. Crowds were growing in the square outside — and growing menacing. Chants of “Death to the ministers!” were increasingly loud. Outside, Lafayette had positioned both National Guards and soldiers around the palace, but by late afternoon they were hard-pressed by the teeming crowds. Some rioters pushed back the National Guard’s lines on one side of the palace all the way to the palace gate.58

Lafayette’s grandson-in-law, Charles de Rémusat, was on the scene as a National Guard officer. He describes seeing the Guard waver under the crowd’s pressure, and one colonel try to calm things down by ordering his men to remove their bayonets. But Lafayette’s adjutant, General Joseph Carbonnel, countermanded that order. Stepping out in between his Guards and the crowd, Carbonnel ordered his men to advance and push the crowd back. With their bayonets fixed, the Guards retained the potential for violence. But critically, the muskets and bayonets weren’t used. All it can take is one gunshot to turn crowd control into a riot or massacre — and Lafayette’s Guardsmen did not open fire. Instead, Rémusat writes, when the Guards showed resolve and pushed forward, the tension seemed to evaporate: “We were touching each other, we were talking, person to person,” he wrote. “It was the most vulgar rabble — but they did not seem very animated to me.” The mob may have been ready to attack the ministers, but they were not eager to attack their fellow citizens in the Guard.59

Lafayette’s grandson-in-law, Charles de Rémusat, was on the scene as a National Guard officer. He describes seeing the Guard waver under the crowd’s pressure, and one colonel try to calm things down by ordering his men to remove their bayonets. But Lafayette’s adjutant, General Joseph Carbonnel, countermanded that order. Stepping out in between his Guards and the crowd, Carbonnel ordered his men to advance and push the crowd back. With their bayonets fixed, the Guards retained the potential for violence. But critically, the muskets and bayonets weren’t used. All it can take is one gunshot to turn crowd control into a riot or massacre — and Lafayette’s Guardsmen did not open fire. Instead, Rémusat writes, when the Guards showed resolve and pushed forward, the tension seemed to evaporate: “We were touching each other, we were talking, person to person,” he wrote. “It was the most vulgar rabble — but they did not seem very animated to me.” The mob may have been ready to attack the ministers, but they were not eager to attack their fellow citizens in the Guard.59

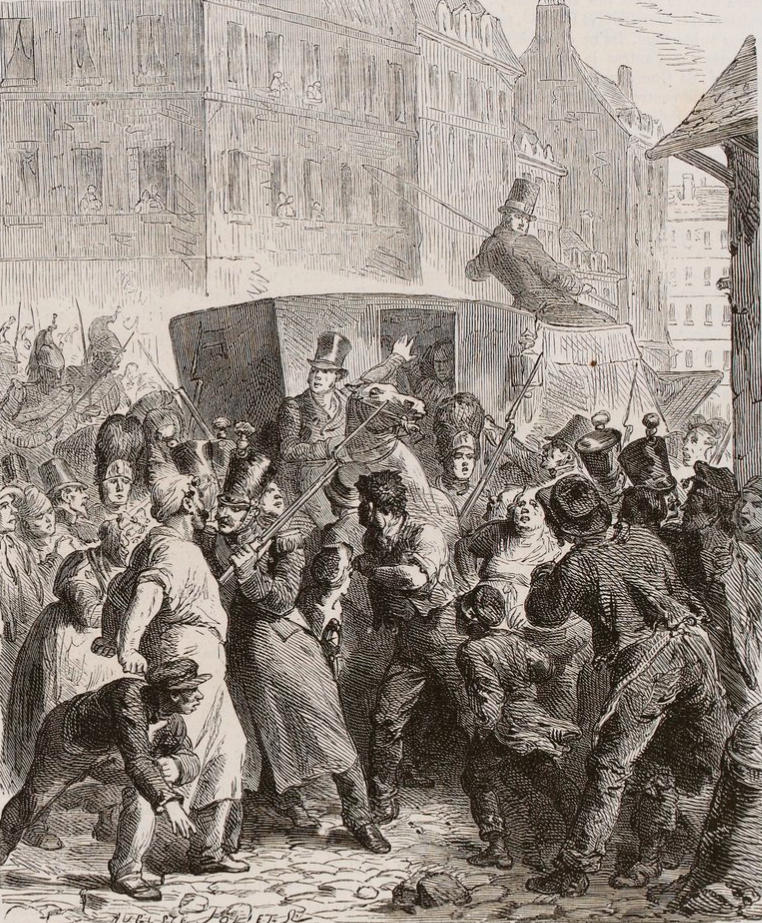

Above: Auguste Joliet, “Procès des ministres (1830),” in Victor Duruy, Histoire populaire contemporaine de la France, vol. 1 (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1864). Public domain via Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Below: Nicolas-Eustache Maurin, “Étienne-Denis Pasquier,” 1832. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Not everyone on scene shared Rémusat’s sanguine take on the surging crowds. Inside the palace, Pasquier hastily adjourned the day’s trial — over the objection of Martignac, who was due to make a rebuttal, and wanted the prosecutor to go at the end of the day so Martignac could prepare his response overnight. But security concerns prevailed; the prisoners were whisked off to their temporary holding cells inside the Luxembourg Palace, and the peers emerged into the square to a chorus of shouts: “Death to the ministers!” The tumultuous crowds prevented carriages from leaving for several hours, until the National Guard rallied and pushed back the Parisians enough to allow an exit. Pasquier himself climbed to an upper story to watch the scene. He was critical of Lafayette, who he felt had deployed his men poorly. But he had nothing but praise for the Guard, which had offered “firm and non-violent resistance” to the crowd: “From the moment it was able to withstand the first shock, it was evident that it would prevail,” Pasquier wrote.60

Not everyone on scene shared Rémusat’s sanguine take on the surging crowds. Inside the palace, Pasquier hastily adjourned the day’s trial — over the objection of Martignac, who was due to make a rebuttal, and wanted the prosecutor to go at the end of the day so Martignac could prepare his response overnight. But security concerns prevailed; the prisoners were whisked off to their temporary holding cells inside the Luxembourg Palace, and the peers emerged into the square to a chorus of shouts: “Death to the ministers!” The tumultuous crowds prevented carriages from leaving for several hours, until the National Guard rallied and pushed back the Parisians enough to allow an exit. Pasquier himself climbed to an upper story to watch the scene. He was critical of Lafayette, who he felt had deployed his men poorly. But he had nothing but praise for the Guard, which had offered “firm and non-violent resistance” to the crowd: “From the moment it was able to withstand the first shock, it was evident that it would prevail,” Pasquier wrote.60

On his way home, Pasquier stopped by the Palais-Royal to meet with Louis-Philippe and the ministers. If Pasquier thought Lafayette too calm in the face of the riot, he found the ministers too panicked. “How can we manage to finish the trial now?” he claimed one of them asked in despair. Pasquier replied that the Peers would not be deterred by the crowds — “provided the road is clear,” he added, “and that depends on the government.”61

The council of ministers agreed to stand firm — and more. That evening, as the crowds around the Luxembourg Palace finally dispersed, a small group of leaders gathered at the Luxembourg to plot an audacious plan for the next day, including Lafayette, Barrot, Pasquier, General Sébastiani — recently moved from the naval ministry to the foreign ministry — and the new interior minister, 29-year-old Camille Bachasson, Comte de Montalivet. These men were here to organize a more robust military defense for December 21, likely to be the final day of the trial. But they were also plotting a scheme they hoped would render all those soldiers unnecessary: to secretly spirit Polignac and the other ministers away, out of the palace and back to the safety of Vincennes, before the crowd realized they were gone.62

The Escape

The plan hatched at this late-night meeting was this: As soon as the prosecution and defense had rested their case, but before the Peers returned a verdict, the four accused would be taken to a waiting carriage in the Luxembourg Palace gardens. A small, inconspicuous troop of cavalry would escort them incognito away from the palace, where they would meet up with a larger cavalry squadron and gallop off to Vincennes. The horsemen would all be regular soldiers, not National Guardsmen, to which Lafayette objected. But some of the National Guard units were known to harbor fierce grudges against the former ministers, and over Lafayette’s protests it was decided that the regular army would be more reliable for this delicate task.63

On December 21, the final day of the trial, almost every single Peer showed up to the heavily guarded Luxembourg Palace. As many as 30,000 soldiers and National Guards swarmed the Left Bank — more than twice as many as Marmont’s entire army during the July Revolution. After being pushed back to the palace gates on the day before, the soldiers now blocked all the streets approaching the palace to keep the square clear.64

Beyond this perimeter were crowds of protesters, small at first and growing steadily as the day went on. Shouts of “Death to the Ministers” were common. But the palace was secure, at least for now, as the trial commenced at 10:30 a.m. Pasquier had secretly urged the Peers to keep things moving, so the trial might wrap up before the crowds got too big. “Keep things moving” turned out to be more of a suggestion than an order for this collection of lawyers and politicians, and there were three hours of speeches by the lawyers for both sides before Pasquier closed the session at 1:30. Now the Peers would retire to deliberate and vote on the ministers’ fates — while the secret plan to save their lives went into effect.65

But the carefully laid plan had almost immediately fallen apart. Stationed in the gardens of the Luxembourg Palace, through which the ministers were supposed to be evacuated, were not regular soldiers but National Guardsmen. And moreover, these particular Guardsmen were from the Parisian suburbs — and were known to be particularly angry at the ministers. Lafayette simply shrugged when Montalivet confronted him about the change of plans: “The National Guardsmen from the suburbs, so energetic and so devoted, had requested a place of honor on this day,” he said. “How could I refuse them?”

Scrambling, Montalivet had his own carriage brought around to a side gate, and quietly approached the National Guards who were guarding it. In a few minutes, he told them, the “condemned” were going to pass through the gate. Their appearance would cause strong emotions. But, he was certain that the “brave citizens” on guard would refrain from any shouts or demonstrations. In so doing, Montalivet did not tell the Guardsmen that the ministers were being spirited away to safety. Instead, he talked about the “severe and just punishments” that would be “meted out to the guilty signatories of the July Ordinances” — implying without actually saying so that the ministers were being taken away to their deaths. Their commander swore that he and his men would obey, and soon after they stood silently as Polignac, Peyronnet, Chauntelauze and Guernon-Ranville were walked past them and into Montalivet’s waiting carriage.66

Scrambling, Montalivet had his own carriage brought around to a side gate, and quietly approached the National Guards who were guarding it. In a few minutes, he told them, the “condemned” were going to pass through the gate. Their appearance would cause strong emotions. But, he was certain that the “brave citizens” on guard would refrain from any shouts or demonstrations. In so doing, Montalivet did not tell the Guardsmen that the ministers were being spirited away to safety. Instead, he talked about the “severe and just punishments” that would be “meted out to the guilty signatories of the July Ordinances” — implying without actually saying so that the ministers were being taken away to their deaths. Their commander swore that he and his men would obey, and soon after they stood silently as Polignac, Peyronnet, Chauntelauze and Guernon-Ranville were walked past them and into Montalivet’s waiting carriage.66

Left: Franz Xaver Winterhalter, portrait of Camille de Montalivet, 1847. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The rest of the plan proceeded as intended. The carriage with the ex-ministers met up with its cavalry escort, and sped out of the city without any incident. They were safe under General Daumesnil’s protection in Vincennes before anyone — National Guards or protesters — knew they were gone.67

Back in the palace, the Peers cast their sentences. All four ministers were overwhelmingly found guilty; that much had never been in doubt. For the more serious question of their sentences, there were some Peers who thought Polignac, if not the others, should be sentenced to death. But they were in the minority. Instead, as the Peers deliberated — and deliberated, and deliberated, for nearly eight hours — they eventually coalesced around sentencing all four men to life in prison. They were also stripped of a host of titles and deprived of some of their civil rights. Already locked up in Vincennes, the four would be promptly shipped to a safer prison 80 miles or 135 kilometers away from Paris.68

Outside, there had been some tussling around 2:30 when a group of protesters tried to force their way into the palace, but reinforcements steadied the line. All around the Luxembourg Palace, the National Guard performed admirably, not only holding their ground but avoiding any provocations. The only exception was the contingent of suburban Guardsmen Lafayette had stationed in the gardens. Proving Montalivet’s judgment correct, when these men found out the ministers had been spirited away, they broke ranks, threw their weapons in the air, and shouted angrily. Lafayette had to come personally to restore order. Then he sent them home. It was 10 p.m., and there were neither prisoners nor judges remaining for them to guard.69

The indispensable man

The crisis was not entirely passed. As news spread of the verdict, there was some rioting the next day, December 22. Many officials feared revolution. Montalivet went so far as to order local mayors to be ready to cut the bell-ropes in their churches, to prevent them being commandeered by revolutionaries to call the people into the streets. But the regime held. The National Guards remained loyal. Groups of university students rejected calls to join protesters, and marched out to support the National Guard instead. Afterwards, many of the students regrouped outside the Palais-Royal, to chant “Long live the King!” at Louis-Philippe. At nightfall it began to rain, and the streets quieted.70

There was one final battle yet to be fought in December 1830, and the National Guard would be intimately involved. But this did not take place on the streets of Paris. It was a political battle over the fate of Lafayette.

The conservative faction in the new regime had disagreed with Lafayette’s progressive politics all along, but there had been nothing they could do about it. Lafayette was both indispensable and viewed with a guarded respect even by his critics. “Very likely [Louis-Philippe] had no choice” but to appoint Lafayette commander-in-chief of the National Guard, wrote the Duc de Broglie in his memoirs. But the duke then continued: “If so, it was fortunate, for there was not in the whole of France or elsewhere another man who was braver, more generous, and more willing to commit himself to any cause where patriotism and humanity were at stake.”71

But now the July Monarchy had faced a crisis on the streets of Paris and come through. The National Guard had stayed loyal, not merely to Lafayette, but to Louis-Philippe and his new regime. So some conservative politicians began to wonder if Lafayette was still indispensable. They rather hoped he wasn’t, because Lafayette continued to use his position and influence to advocate for further reforms. In his official order of the day to the National Guard on December 24, Lafayette wrote that “everything that is possible has been done for the cause of public order, and our recompense is the hope that everything will now be done for the cause of liberty.”72

Instead, the majority of the Chamber of Deputies voted that same day to pass a new law governing the National Guard — declaring, in its 50th article, that no one could command a National Guard unit any bigger than that of a city. In other words, Lafayette’s role as commander-in-chief of the National Guard for all of France was abolished, along with his formal power base.73

In response, Lafayette submitted his resignation to Louis-Philippe. The Chamber might not think him indispensable any more, but the king surely did. After all, just two days before, the king had written a letter to Lafayette, thanking him “above all” others, praising his “courage, patriotism, and respect for the laws,” saying the king counted on Lafayette’s continued efforts, and assuring him of “the sincere friendship you know I have for you.”74

And Louis-Philippe indeed did not want Lafayette to resign. Neither did Jacques Laffitte. At the very least, not now, not like this. They asked him to hold off on anything drastic, and the king and his ministers both spoke with Lafayette to try and find an agreement.75

The problem was that Lafayette didn’t really care about being commander-in-chief of the National Guard. To be sure, he was insulted. But he knew his position commanding the National Guard of the entire country was “irregular”; he just thought he had “earned the right to stay until he chose to step down,” as Lafayette’s biographer and friend of the show Mike Duncan put it.76 What Lafayette really wanted was broader-based political reforms — moves toward the “popular monarchy surrounded by republican institutions” that Louis-Philippe had said he supported five months earlier.

Specifically, Lafayette made three demands. First, the Chamber of Peers had to be abolished, and replaced with a new body, “composed of sincere friends of the revolution.” Second, there should be prompt new elections for the Chamber of Deputies. And finally, he demanded a cabinet reshuffle, with progressives put in charge of the Interior and Foreign ministries. “The situation allows for only one Minister of the Interior: Odilon Barrot,” Lafayette said. And a progressive foreign minister might help commit the July Monarchy to supporting the cause of liberty elsewhere in Europe, as Lafayette thought France had a duty to do. If all that was done, then Lafayette would agree to stay on in the lesser role of commander of the Paris National Guard.77

But the old revolutionary had overplayed his hand. Louis-Philippe liked Lafayette and wanted to keep him — but this was way too much. The king considered Lafayette’s demands unacceptable, and decided to call his bluff. He wrote a short note back to Lafayette, expressing his regret over how things turned out and accepting the general’s resignation. “I will take steps to ensure that [command of the Guard] is not interrupted, and to fill the void that I so much wanted to prevent and which causes me so much distress,” the king wrote. “It is always with all my heart, my dear General, that I assure you of my sincere and unwavering friendship for you.”78

It was December 26, 1830. Lafayette was gone. To be sure, he was still a member of the Chamber of Deputies, and would use this podium to continue to advocate for his left-wing policies. But he was no longer the indispensable man.